The Captain, May 1910

I

IT was about four o’clock on a mellow afternoon in early April. The sun was shining brightly, birds sang, and rabbits sported in the undergrowth. Everything, so to speak, in the garden was lovely. At a point some four miles from Sedleigh School, in the direction of Lower Borlock, the scenic arrangements were particularly fine. The sun seemed to shine more brightly; rather more birds were singing; there was a slightly more animated look about the increased number of rabbits that sported in the undergrowth. It was a spot where every prospect pleased, and only man was vile.

Man was represented by W. J. Stone, of Outwood’s. He was sitting on a rustic stile, enjoying the sun, listening to the birds, and observing the rabbits, but—more particularly—smoking. He had not come to that lovely, lonely spot because it was lovely. He had come because it was lonely. Here, of all places, four miles from the school, a man might enjoy his after-luncheon cigarette in peace. It was a pity that there was no faithful friend on hand to watch him enjoy it. It takes two to smoke properly at school—one to smoke, the other to stand by and remark with unwilling admiration, “I say, you are an ass, you know!” He could have wished that Robinson, also of Outwood’s, had been at his side. But Robinson had his duties elsewhere. Robinson had to be at roll-call to answer his name—and Stone’s.

So Stone sat on his stile alone, and thought of life, drawing meditatively at his cigarette. He congratulated himself on having chosen not only the ideal spot, but also the ideal time. There was a match on to-day, School v. Town, and all the masters who were not playing golf would be on the touch-line. Sedleigh, as Mr. Downing, the games-master, liked to say, was above all a keen school; and its keenness extended to the staff.

It seemed to Stone that nothing could undo him. But Nemesis was lumbering round the corner, in the person, the stout person, of one Collard, the school sergeant.

The stile on which Stone sat had just one disadvantage. It was a little far back from the road, so that he could not see pedestrians until they came immediately opposite to him. Also there was a broad strip of turf between the hedge and the road. Also, again, Sergeant Collard suffered from tender feet. Therefore the Sergeant, journeying to the Lower Borlock railway station, walked not on the road but on the turf. Consequently his footsteps were noiseless, with the result—now we come to the point—that he came into view of the stile, Stone, and the cigarette while all three were in conjunction. Stone was, indeed, in the very act of expelling a cloud of smoke.

Stone did what he could. He flung the cigarette into the field behind him, and looked at the sergeant with innocent pleasure, as one meeting a friend unexpectedly in distant parts.

The sergeant halted.

“Oo-oo-oo, yes!” he observed.

He generally opened conversation in this way.

“Lovely afternoon, Sergeant,” said Stone. “Ripping, this sun is.”

The Sergeant eyed him sternly.

“And the birds,” said Stone.

“Oo-oo-yes, you young monkey!” said Sergeant Collard.

“And the rabbits,” said Stone.

The Sergeant continued to eye him with his basilisk stare.

It so happened that Stone was not one of his favourites. Indeed, between Stone and himself there had long been raging guerilla warfare of a somewhat poignant kind. It was Stone who, to the great contentment of the school, had bestowed upon him the nickname of Boots. And he considered it derogatory to the dignity of an ex-sergeant of his Majesty’s army to be addressed as Boots by ribald boys.

It was not, therefore, with pain that he realised that duty compelled him to report to Mr. Outwood that he had discovered Stone smoking on a stile four miles from the school in the direction of Lower Borlock. Pleasure, rather.

“Oo-oo-oo yes!” he said. “Smoking, eh?”

Stone stared.

“Smoking?” he cried. “Me?”

“Smoking. Contrary to school regulations, as is well known. Young monkey!”

“Boots,” said Stone, “you’re delirious.”

The Sergeant turned a richer purple at the hated name.

“Never you mind my boots,” he said crisply. “I shouldn’t like to be in yours when I tells Mr. Outwood how you was smoking contrary to school regulations.”

“You’re going to tell him that?”

“I am going to tell him that.”

“Where’s your evidence?”

“Hevidence! Didn’t I cop yer at it?”

“Cop me at it!” said Stone, amazed. “If you did, why aren’t I smoking now? Dash it!” he moaned, “it’s a bit thick. I come here, miles from the school, simply to get away from you and have a little peace, and I’m blowed if you don’t follow me. And not only that, you accuse me, absolutely without evidence, of smoking. I call it rough on a chap.”

“I seen yer throw the cigarette away. There it is behind you.”

“And you mean to say,” demanded Stone, “that just because I happen by the merest fluke to be sitting on a stile within a dozen yards of a cigarette which may have been there goodness knows how long——”

“Ho! May it? Then why is it alight now?”

Stone looked behind him. A thin spiral of smoke was indeed curling up from the grass.

“What’s that, then?” asked Sergeant Collard, pointing.

Stone gave the smoke a careful inspection.

“It looks to me,” he said, “like a prairie fire. Probably caused by spontaneous combustion owing to the heat of the day.”

“Ho!” said the Sergeant. “It looks to me like a cigarette thrown away by some young monkey because he was copped in the act of smoking it.”

“As a matter of fact,” said Stone carelessly, “I remember now. It is a cigarette. A man stopped here just now to ask the time. I recollect now he threw away his cigarette. So that’s how it was, you see. Now you see how silly it is to jump at conclusions, don’t you, sergeant?”

“Ho!”

“By the way, sergeant,” said Stone, “I’ve been meaning to buy your son Ernie some sweets for days. Suppose you take this, and——”

He fumbled in his pocket.

Sergeant Collard snorted ruthlessly.

“Attempted bribery!” he boomed. “Thereby haggravatin’ the offence. Mr. Outwood shall ’ear of that, too.”

Stone gave the thing up.

“Oh, get out, Boots,” he said moodily. “You’re a blot on the landscape.”

For some moments after the sergeant had trudged off, Stone sat on the stile, pondering. It was uncommonly awkward. There was no blinking that fact. Corporal punishment, worse luck, was rarely administered at Sedleigh, the headmaster objecting to it on principle. He would not have minded that. It only lasted a few moments, and when it was over, there you were with a clean slate. The punishment for smoking would be either lines to a colossal amount or else detention on three or more half-holidays. To these penalties he objected strongly.

He climbed down from the stile, and started to walk towards the school. Life was very grey. The sun still shone, the birds still sang, the rabbits still sported in the undergrowth, but Stone recked of none of these things. He was plunged in gloomy thoughts.

Now, I could haul up my slacks with considerable vim on the subject of Stone’s thoughts; I could work the whole thing up into a fine psychological study, rather in the Henry James style; but it would only be cut out by the editor, so what’s the use? Let us, therefore, imagine Stone plunged in gloomy thoughts for about three minutes, or four, and then—make it five—at the end of five minutes hearing the droning sound.

At first the sound was simply like the note of some distant bee (or wasp). Then it came nearer, and Stone knew it for what it was, the noise of a powerful motor-car.

It gave him no idea at first beyond the very sensible one of getting out of the road. He got out of the road, and presently the car shot past—a big, red car with one occupant.

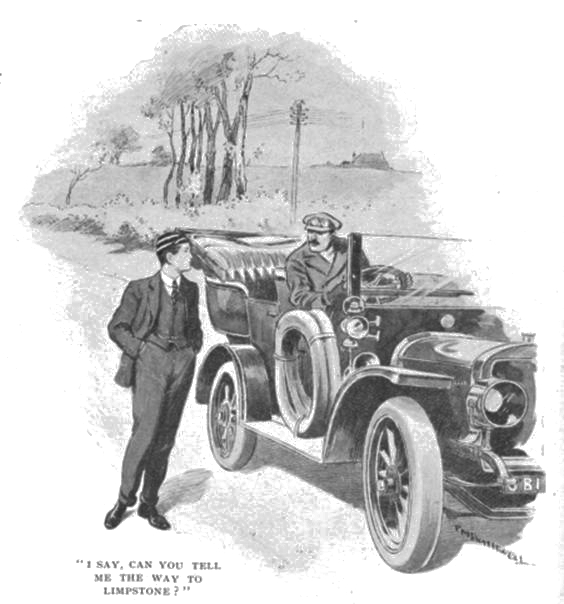

Stone watched it disappearing down the road, and was starting once more on his walk when he observed the machine slow down, stop, and begin to back towards him. In a few moments the motorist, coming within hailing distance, hailed.

“I say!” he shouted.

“Hullo?” said Stone.

The car drew level with him. The driver leaned out.

“I say,” he said, “can you tell me the way to Limpstone?”

“You’re going just in the wrong direction,” said Stone. “You’re coming away from it.”

The driver made disparaging comments on the rustic intelligence.

“An old fossil in a smock told me this was the way a quarter of an hour ago.”

“You ought to have turned at the bend in the road, where the sign-post says ‘To Sedleigh’—oh!”

He gasped. An idea had come to him.

“I say,” he added tentatively, “I suppose you couldn’t—what I mean is, if you would let me hop into the car, I could show you the way. I’m going to Sedleigh, and it’s straight on from there to Limpstone.”

“Hop on,” said the driver, briefly. “You’re the man I’ve been wanting to meet.”

“Same here,” said Stone, hopping.

The car moved off.

“What sort of a road is it from here?” said the motorist, as they turned down the bend.

“Quite good.”

“Then sit tight. I’m going to let her rip. I’m all behind time already.”

He opened the throttle. The next few minutes were almost too exhilarating to Stone’s thinking. The car touched the road here and there, but for the most part it seemed to skim through the air like an aeroplane. Every now and then it would turn a corner on the rim of one wheel. At an early point in the proceedings Stone lost his breath. He had to hold on to his cap to keep from losing that too. It was with a feeling of profound relief that he observed the school buildings approaching as if on wings.

“Hi!” he shouted in his companion’s ear. “Stop!” The car gradually lessened its speed.

“This is Sedleigh,” said Stone. “Will you put me down here? Thanks awfully for the lift. You go straight on now till you get into the London road. You turn down to the right for Limpstone.”

“Thanks,” said the motorist briefly. “Good-bye.”

“Good-bye.”

II

From the school grounds, as Stone turned towards them, came an intermittent bellowing, rather suggestive of a deinosaurus in pain. This was the school (“we are above all a keen school”) stimulating the fifteen in its battle with the Town. Just as Stone went in at the gate the bellowing changed to a howl, which grew in volume till it died away in a patter of clapping. Stone knew what that meant. Somebody had scored for the school.

He mingled with the crowd on the touch-line, and found Robinson.

“Hullo!” said Robinson. “Are you back?”

“Quick, tell me all that’s happened,” said Stone; “who was that who scored just now?”

“Hammond. Jolly good run. Got the ball from a scrum in our twenty-five and nipped clean through. The back almost had him, but he swerved.”

Stone’s lips moved. He wore an air of concentration.

“Hammond—our twenty-five—back—swerve,” he murmured. “Is that the only score?”

“So far.”

“Anything else happened?”

“The Town nearly got over with a forward rush in the first five minutes. That big chap with red hair started it.”

“Who’s been doing anything for us?”

“Hammond’s been good all through. Hassall nearly dropped a goal.”

“Any of the forwards do anything?”

“Williams pretty hot in the loose.”

“Thanks.”

A few minutes later the whistle blew for “No-side,” leaving the School winners by a try to nil. Stone joined the crowd that moved towards the houses. His gaze wandered to and fro. At last he discovered the man he was looking for—Mr. Downing.

He trotted up.

“Jolly good game, sir,” he said.

Mr. Downing was in affable mood. The School had won against a heavier team, and the winning try had been scored by a boy in his house. He beamed upon Stone.

“Excellent, Stone, excellent,” he said. “The team played a good, keen game all through.”

“Fine run of Hammond’s, sir.”

“Very fine. Quite brilliant.”

Stone dipped into the coffers of his memory and produced Hassall.

“Good shot at a dropped goal, that one of Hassall’s, wasn’t it, sir?”

“Very good indeed. It was the only thing to do, and it nearly succeeded.”

“It was an awfully good game altogether,” said Stone. “I thought they were over in the first five minutes when that red-haired forward started that rush.”

Mr. Downing agreed that it had been a very near thing. Stone, after a casual mention of Williams’ good work in the loose, went off to his house.

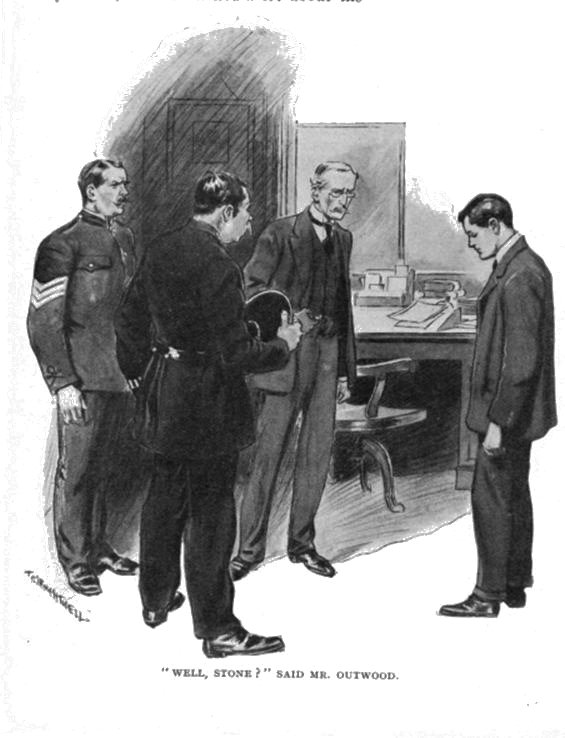

Just before tea, as he expected, he was summoned to Mr. Outwood’s study. It was quite a small party. Sergeant Collard was there, looking stout and important, but no other representatives of the Sedleigh Smart Set were present.

Mr. Outwood, that mild-mannered archæologist, peered at Stone over his pince-nez. He looked troubled.

“Stone,” he said.

“Sir?” said Stone.

“Er——”

“Yes, sir?”

“Perhaps, sergeant,” said Mr. Outwood, “it would be better if you told your story again.”

“Oo-oo-oo yes, sir,” responded the man of war, amiably. “In ’arf a minute, sir.”

He proceeded to relate how he had found Stone seated on a stile near Lower Borlock, smoking.

“Leastways,” concluded the sergeant, “ ’e’d flung away the cigaroot prompt hon seein’ me. Young monkey! But I spotted ’im, sir. Prompt.”

Stone’s face during this recital was a study in injured astonishment.

“I think the sergeant must be mistaken, sir,” he said with unction. “Smoking is against school rules, and is bad for you, too.”

“Mistook!” boomed the sergeant. “Me! Why, I seen you with my own eyes. Yes, and talked to you, too.”

“Talked to me?”

“Yes, talked to you. Young monkey!”

“What time was it?”

“Yes, what time, sergeant?” interpolated Mr. Outwood. “That is important. I caught sight of a boy who I am nearly sure was Stone, though I had no reason to impress the fact on my memory, immediately after the conclusion of the football match. That would be shortly after four.”

“And fortunately, sir,” said Stone smoothly, “I happened to meet Mr. Downing just as the match finished. You can ask him, if you like, sir. We talked a lot about the match. I remember, now I come to think of it, that we talked about how nearly the Town scored in the first five minutes.”

“In the first five minutes!” shouted the sergeant. “Oo-oo-oo yer, you young monkey; I seen you with my own eyes sitting on that stile at four prompt. I’d just looked at my watch.”

Mr. Outwood was plainly puzzled.

“Didn’t you have sun-stroke once when you were serving in India, sergeant?” asked Stone with friendly interest. “I seem to remember hearing you tell some of the chaps that you had.”

“I ’ad sun-stroke, yes,” admitted the sergeant. “But I ’adn’t this afternoon when I saw you a-sittin’ and smokin’ on that stile,” he said doggedly.

Stone looked appealingly at Mr. Outwood. The housemaster, in his motherly way, began to reason with the invalid.

“But really, sergeant, I think— Surely. You follow me? This stile you speak of as having been near Lower Borlock. That village is quite four miles from the school. I know from personal experience. There is a church there, portions of which date back to pre-Norman times. I have frequently bicycled to it.”

“Of course, if I had been there and had had my bicycle, sir,” said Stone, as one who insists on being reasonable, “I might have got back in time for the finish of the game; but my bicycle is being mended. Had the fellow you thought you saw, sergeant, a bicycle?”

“I didn’t see no bicycle.”

“Then I think you will agree, sergeant,” said Mr. Outwood, soothingly, “that the whole thing must have been a mistake. The effects of sun-stroke frequently reappear in after-life, I believe, and——”

“I saw ’im on that stile a-smokin’,” persisted the seer of visions.

“You fancied you did,” said Mr. Outwood. “Probably you were thinking of Stone at the moment——”

“He’s always thinking of me, sir,” said Stone with an affectionate glance at the perspiring warrior.

“That is how it all happened,” beamed Mr. Outwood. “You see, sergeant, Stone could not possibly have covered the distance in the time on foot, so that——”

He was interrupted by a knock at the door. One of the maids entered.

“Might I speak to you for a moment, sir?”

“Certainly, Jane. Excuse me one instant.”

He went out. There were sounds of a murmured conversation in the passage. During the interval Sergeant Collard and Stone eyed one another in silence, the Sergeant with something of the Gorgon in his gaze, Stone all cheery friendliness. Presently Mr. Outwood came back.

“Certainly, Jane,” he said over his shoulder. “Show him in here.”

Stone was wondering who “him” referred to, when there came from outside the sound of ponderous footsteps, and into the room walked a policeman, who, having apparently recognised an acquaintance in Sergeant Collard, nodded to him, and stood at ease, breathing heavily.

“Yes, constable?” said Mr. Outwood. “What is it that I can do for you?”

The policeman cleared his throat.

“It’s like this, sir,” he said.

Fixing an absolutely expressionless eye on an engraving that hung over the mantelpiece, he began to speak in what was evidently the manner he reserved for giving evidence before magistrates.

“On the afternoon of the—I mean this afternoon, at five minutes after four o’clock, I was on the road between Lower Borlock and Sedleigh, when I heard a sound, and round the corner came dashing a nortermobile.”

“I beg your pardon, constable?”

“A nortermobile, your worsh—sir. A red one, sir, exceeding of the speed limit by a matter of eighty miles a hower. Why,” he went on, dropping the official manner and speaking with a touch of human heat, “if I ’adn’t looked precious slippy it ’ud have knocked me into hash. It was all hover so quick and such a shock I ’ad, that cop his number was more than I could do. He was off in a flash. The only thing I saw was that there was a young gent sittin’ beside the shovoor with a red and blue striped cap. One of the young gents from the school, as likely as not, I thinks. And, makin’ inquiries, I finds that the young gents in your house wears red and blue striped caps, sir.”

“Yes, yes; that is so, constable.”

“Why,” said the policeman, for the first time seeing Stone, “same colours as this young gent ’ere ’as on his tie. And blow me if I don’t think that was the very young gent——”

He looked at Stone. Mr. Outwood looked at Stone. Sergeant Collard looked at Stone. Stone looked at the carpet.

The silence was broken by the voice of the man of war, raised in a psalm of triumph.

“Sunstroke! Oo-oo-oo. Yes! Sunstroke? Ho! Young monk——”

Mr. Outwood was still looking at Stone with eyes from which the scales had fallen.

“Well, Stone?” he said.

Editors’ notes:

Printer’s errors corrected above:

In part II, magazine had “a howl, with grew in volume”; altered to “which” following editors of Tales of Wrykyn and Elsewhere.

Magazine had “mild-manner archæologist”; corrected to “mild-mannered” as in 1923 Boys’ Life reprint.

Magazine had “if I had been there and had had my bicycle sir,”; comma added after “bicycle” for the sake of grammar, and as in 1923 reprint.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums