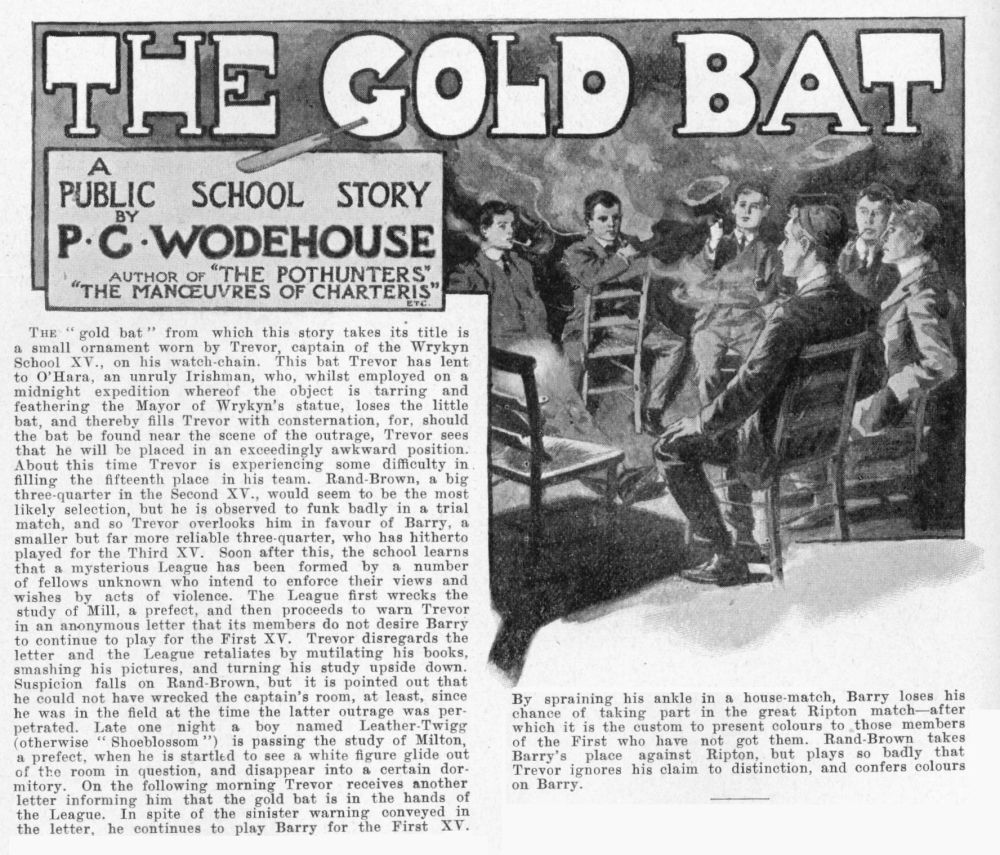

The Captain, February 1904

CHAPTER XVII.

The Watchers in the Vault.

OR

the next three seconds you could have heard a cannonball drop. And that

was equivalent, in the senior day-room at Seymour’s, to a dead silence.

Barry stood in the middle of the room leaning on the stick on which he

supported life, now that his ankle had been injured, and turned red and white

in regular rotation, as the magnificence of the news came home to him.

OR

the next three seconds you could have heard a cannonball drop. And that

was equivalent, in the senior day-room at Seymour’s, to a dead silence.

Barry stood in the middle of the room leaning on the stick on which he

supported life, now that his ankle had been injured, and turned red and white

in regular rotation, as the magnificence of the news came home to him.

Then the small voice of Linton was heard.

“That’ll be six d. I’ll trouble you for, young Sammy,” said Linton. For he had betted an even sixpence with Master Samuel Menzies that Barry would get his first fifteen cap this term, and Barry had got it.

A great shout went up from every corner of the room. Barry was one of the most popular members of the house, and every one had been sorry for him when his sprained ankle had apparently put him out of the running for the last cap.

“Good old Barry,” said Drummond, delightedly. Barry thanked him in a dazed way.

Every one crowded in to shake his hand. Barry thanked them all in a dazed way.

And then the senior day-room, in spite of the fact that Milton had returned, gave itself up to celebrating the occasion with one of the most deafening uproars that had ever been heard even in that factory of noise. A babel of voices discussed the match of the afternoon, each trying to outshout the other. In one corner Linton was beating wildly on a biscuit-tin with part of a broken chair. Shoeblossom was busy in the opposite corner executing an intricate step-dance on somebody else’s box. McTodd had got hold of the red-hot poker, and was burning his initials in huge letters on the seat of a chair. Every one, in short, was enjoying himself, and it was not until an advanced hour that comparative quiet was restored. It was a great evening for Barry, the best he had ever experienced.

Clowes did not learn the news till he saw it on the notice-board, on the following Monday. When he saw it he whistled softly.

“I see you’ve given Barry his first,” he said to Trevor, when they met. “Rather sensational.”

“Milton and Allardyce both thought he deserved it. If he’d been playing instead of Rand-Brown, they wouldn’t have scored at all probably, and we should have got one more try.”

“That’s all right,” said Clowes. “He deserves it right enough, and I’m jolly glad you’ve given it him. But things will begin to move now, don’t you think? The League ought to have a word to say about the business. It’ll be a facer for them.”

“Do you remember,” asked Trevor, “saying that you thought it must be Rand-Brown who wrote those letters?”

“Yes. Well?”

“Well, Milton had an idea that it was Rand-Brown who ragged his study.”

“What made him think that?”

Trevor related the Shoeblossom incident.

Clowes became quite excited.

“Then Rand-Brown must be the man,” he said. “Why don’t you go and tackle him? Probably he’s got the bat in his study.”

“It’s not in his study,” said Trevor, “because I looked everywhere for it, and got him to turn out his pockets, too. And yet I’ll swear he knows something about it. One thing struck me as a bit suspicious. I went straight into his study and showed him that last letter—about the bat, you know, and accused him of writing it. Now, if he hadn’t been in the business somehow, he wouldn’t have understood what was meant by their saying ‘the bat you lost.’ It might have been an ordinary cricket-bat for all he knew. But he offered to let me search the study. It didn’t strike me as rum till afterwards. Then it seemed fishy. What do you think?”

Clowes thought so too, but admitted that he did not see of what use the suspicion was going to be. Whether Rand-Brown knew anything about the affair or not, it was quite certain that the bat was not with him.

O’Hara, meanwhile, had decided that the time had come for him to resume his detective duties. Moriarty agreed with him, and they resolved that that night they would patronise the vault instead of the gymnasium, and take a holiday as far as their boxing was concerned. There was plenty of time before the Aldershot competition.

Lock-up was still at six, so at a quarter to that hour they slipped down into the vault, and took up their position.

A quarter of an hour passed. The lock-up bell sounded faintly. Moriarty began to grow tired.

“Is it worth it?” he said, “an’ wouldn’t they have come before, if they meant to come?”

“We’ll give them another quarter of an hour,” said O’Hara. “After that——”

“Sh!” whispered Moriarty.

The door had opened. They could see a figure dimly outlined in the semi-darkness. Footsteps passed down into the vault, and there came a sound as if the unknown had cannoned into a chair, followed by a sharp intake of breath, expressive of pain. A scraping sound, and a flash of light, and part of the vault was lit by a candle. O’Hara caught a glimpse of the unknown’s face as he rose from lighting the candle, but it was not enough to enable him to recognise him. The candle was standing on a chair, and the light it gave was too feeble to reach the face of any one not on a level with it.

The unknown began to drag chairs out into the neighbourhood of the light. O’Hara counted six.

The sixth chair had scarcely been placed in position when the door opened again. Six other figures appeared in the opening one after the other, and bolted into the vault like rabbits into a burrow. The last of them closed the door after them.

O’Hara nudged Moriarty, and Moriarty nudged O’Hara; but neither made a sound. They were not likely to be seen—the blackness of the vault was too Egyptian for that—but they were so near to the chairs that the least whisper must have been heard. Not a word had proceeded from the occupants of the chairs so far. If O’Hara’s suspicion was correct, and this was really the League holding a meeting, their methods were more secret than those of any other secret society in existence. Even the Nihilists probably exchanged a few remarks from time to time, when they met together to plot. But these men of mystery never opened their lips. It puzzled O’Hara.

The light of the candle was obscured for a moment, and a sound of puffing came from the darkness.

O’Hara nudged Moriarty again.

“Smoking!” said the nudge.

Moriarty nudged O’Hara.

“Smoking it is!” was the meaning of the movement.

A strong smell of tobacco showed that the diagnosis had been a true one. Each of the figures in turn lit his pipe at the candle, and sat back, still in silence. It could not have been very pleasant, smoking in almost pitch darkness, but it was breaking rules, which was probably the main consideration that swayed the smokers. They puffed away steadily, till the two Irishmen were wrapped about in invisible clouds.

Then a strange thing happened. I know that I am infringing copyright in making that statement, but it so exactly suits the occurrence that perhaps Mr. Rider Haggard will not object. It was a strange thing that happened.

A rasping voice shattered the silence.

“You boys down there,” said the voice, “come here immediately. Come here, I say.”

It was the well-known voice of Mr. Robert Dexter, O’Hara and Moriarty’s beloved housemaster.

The two Irishmen simultaneously clutched one another, each afraid that the other would think—from force of long habit—that the housemaster was speaking to him. Both stood where they were. It was the men of mystery and tobacco that Dexter was after, they thought.

But they were wrong. What had brought Dexter to the vault was the fact that he had seen two boys, who looked uncommonly like O’Hara and Moriarty, go down the steps of the vault at a quarter to six. He had been doing his usual after-lock-up prowl on the junior gravel, to intercept stragglers, and he had been a witness—from a distance of fifty yards, in a very bad light—of the descent into the vault. He had remained on the gravel ever since, in the hope of catching them as they came up; but as they had not come up, he had determined to make the first move himself. He had not seen the six unknowns go down, for, the evening being chilly, he had paced up and down, and they had by a lucky accident chosen a moment when his back was turned.

“Come up immediately,” he repeated.

Here a blast of tobacco-smoke rushed at him from the darkness. The candle had been extinguished at the first alarm, and he had not realised—though he had suspected it—that smoking had been going on.

A hurried whispering was in progress among the unknowns. Apparently they saw that the game was up, for they picked their way towards the door.

As each came up the steps and passed him, Mr. Dexter observed “Ha!” and appeared to make a note of his name. The last of the six was just leaving him after this process had been completed, when Mr. Dexter called him back.

“That is not all,” he said, suspiciously.

“Yes, sir,” said the last of the unknowns.

Neither of the Irishmen recognised the voice. Its owner was a stranger to them.

“I tell you it is not,” snapped Mr. Dexter. “You are concealing the truth from me. O’Hara and Moriarty are down there—two boys in my own house. I saw them go down there.”

“They had nothing to do with us, sir. We saw nothing of them.”

“I have no doubt,” said the housemaster, “that you imagine that you are doing a very chivalrous thing by trying to hide them, but you will gain nothing by it. You may go.”

He came to the top of the steps, and it seemed as if he intended to plunge into the darkness in search of the suspects. But, probably realising the futility of such a course, he changed his mind, and delivered an ultimatum from the top step.

“O’Hara and Moriarty.”

No reply.

“O’Hara and Moriarty, I know perfectly well that you are down there. Come up immediately.”

Dignified silence from the vault.

“Well, I shall wait here till you do choose to come up. You would be well advised to do so immediately. I warn you you will not tire me out.”

He turned, and the door slammed behind him.

“What’ll we do?” whispered Moriarty. It was at last safe to whisper.

“Wait,” said O’Hara, “I’m thinking.”

O’Hara thought. For many minutes he thought in vain. At last there came flooding back into his mind a memory of the days of his faghood. It was after that that he had been groping all the time. He remembered now. Once in those days there had been an unexpected function in the middle of term. There were needed for that function certain chairs. He could recall even now his furious disgust when he and a select body of fellow fags had been pounced upon by their form-master, and coerced into forming a line from the junior block to the cloisters, for the purpose of handing chairs. True, his form-master had stood ginger-beer after the event, with princely liberality, but the labour was of the sort that gallons of ginger-beer will not make pleasant. But he ceased to regret the episode now. He had been at the extreme end of the chair-handling chain. He had stood in a passage in the junior block, just by the door that led to the masters’ garden, and which—he remembered—was never locked till late at night. And while he stood there, a pair of hands—apparently without a body—had heaved up chair after chair through a black opening in the floor. In other words, a trapdoor connected with the vault in which he now was.

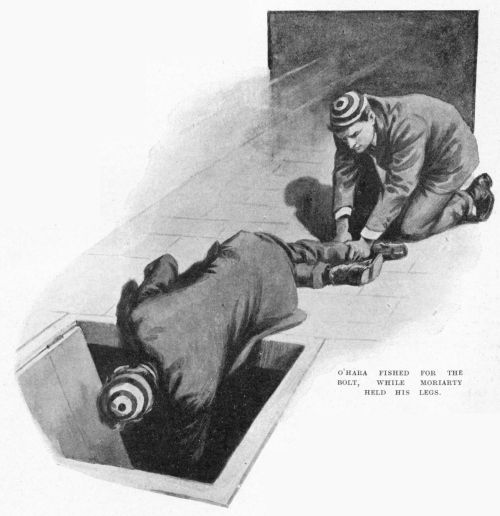

He imparted these reminiscences of childhood to Moriarty. They set off to search for the missing door, and, after wanderings and barkings of shins too painful to relate, they found it. Moriarty lit a match. The light fell on the trapdoor, and their last doubts were at an end. The thing opened inwards. The bolt was on their side, not in the passage above them. To shoot the bolt took them one second, to climb into the passage one minute. They stood at the side of the opening, and dusted their clothes.

“Bedad!” said Moriarty, suddenly.

“What?”

“Why, how are we to shut it?”

This was a problem that wanted some solving. Eventually they managed it, O’Hara leaning over and fishing for it, while Moriarty held his legs.

As luck would have it—and luck had stood by them well all through—there was a bolt on top of the trapdoor, as well as beneath it.

“Supposing that had been shot!” said O’Hara, as they fastened the door in its place.

Moriarty did not care to suppose anything so unpleasant.

Mr. Dexter was still prowling about on the junior gravel, when the two Irishmen ran round and across the senior gravel to the gymnasium. Here they put in a few minutes’ gentle sparring, and then marched boldly up to Mr. Day (who happened to have looked in five minutes after their arrival) and got their paper.

“What time did O’Hara and Moriarty arrive at the gymnasium?” asked Mr. Dexter of Mr. Day next morning.

“O’Hara and Moriarty? Really, I can’t remember. I know they left at about a quarter to seven.”

That profound thinker, Mr. Tony Weller, was never so correct as in his views respecting the value of an alibi. There are few better things in an emergency.

CHAPTER XVIII.

O’Hara Excels Himself.

T

was Renford’s turn next morning to get up and feed the ferrets. Harvey

had done it the day before.

T

was Renford’s turn next morning to get up and feed the ferrets. Harvey

had done it the day before.

Renford was not a youth who enjoyed early rising, but in the cause of the ferrets he would have endured anything, so at six punctually he slid out of bed, dressed quietly, so as not to disturb the rest of the dormitory, and ran over to the vault. To his utter amazement he found it locked. Such a thing had never been done before in the whole course of his experience. He tugged at the handle, but not an inch or a fraction of an inch would the door yield. The policy of the Open Door had ceased to find favour in the eyes of the authorities.

A feeling of blank despair seized upon him. He thought of the dismay of the ferrets when they woke up and realised that there was no chance of breakfast for them. And then they would gradually waste away, and some day somebody would go down to the vault to fetch chairs, and would come upon two mouldering skeletons, and wonder what they had once been. He almost wept at the vision so conjured up.

There was nobody about. Perhaps he might break in somehow. But then there was nothing to get to work with. He could not kick the door down. No, he must give it up, and the ferrets’ breakfast-hour must be postponed. Possibly Harvey might be able to think of something.

“Fed ’em?” inquired Harvey, when they met at breakfast.

“No, I couldn’t.”

“Why on earth not? You didn’t oversleep yourself?”

Renford poured his tale into his friend’s shocked ears.

“My hat!” said Harvey, when he had finished, “what on earth are we to do? They’ll starve.”

Renford nodded mournfully.

“Whatever made them go and lock the door?” he said.

He seemed to think the authorities should have given him due notice of such an action.

“You’re sure they have locked it? It isn’t only stuck or something?”

“I lugged at the handle for hours. But you can go and see for yourself if you like.”

Harvey went, and, waiting till the coast was clear, attached himself to the handle with a prehensile grasp, and put his back into one strenuous tug. It was even as Renford had said. The door was locked beyond possibility of doubt.

Renford and he went over to school that morning with long faces and a general air of acute depression. It was perhaps fortunate for their purpose that they did, for had their appearance been normal it might not have attracted O’Hara’s attention. As it was, the Irishman, meeting them on the junior gravel, stopped and asked them what was wrong. Since the adventure in the vault, he had felt an interest in Renford and Harvey.

The two told their story in alternate sentences like the Strophe and Antistrophe of a Greek chorus. (“Steichomuthics,” your Greek scholar calls it, I fancy. Ha, yes! Just so.)

“So ye can’t get in because they’ve locked the door, an’ ye don’t know what to do about it?” said O’Hara, at the conclusion of the narrative.

Renford and Harvey informed him in chorus that that was the state of the game up to present date.

“An’ ye want me to get them out for you?”

Neither had dared to hope that he would go so far as this. What they had looked for had been at the most a few thoughtful words of advice. That such a master-strategist as O’Hara should take up their cause was an unexampled piece of good luck.

“If you only would,” said Harvey.

“We should be most awfully obliged,” said Renford.

“Very well,” said O’Hara.

They thanked him profusely.

O’Hara replied that it would be a privilege. He should be sorry, he said, to have anything happen to the ferrets.

Renford and Harvey went on into school feeling more cheerful. If the ferrets could be extracted from their present tight corner, O’Hara was the man to do it.

O’Hara had not made his offer of assistance in any spirit of doubt. He was certain that he could do what he had promised. For it had not escaped his memory that this was a Tuesday—in other words, a mathematics morning up to the quarter to eleven interval. That meant, as has been explained previously, that, while the rest of the school were in the form-rooms, he would be out in the passage, if he cared to be. There would be no witnesses to what he was going to do.

But, by that curious perversity of fate which is so often noticeable, Mr. Banks was in a peculiarly lamb-like and long-suffering mood this morning. Actions for which O’Hara would on other days have been expelled from the room without hope of return, to-day were greeted with a mild “Don’t do that, please, O’Hara,” or even the ridiculously inadequate “O’Hara!” It was perfectly disheartening. O’Hara began to ask himself bitterly what was the use of ragging at all if this was how it was received. And the moments were flying, and his promise to Renford and Harvey still remained unfulfilled.

He prepared for fresh efforts.

So desperate was he, that he even resorted to crude methods like the throwing of paper balls and the dropping of books. And when your really scientific ragger sinks to this, he is nearing the end of his tether. O’Hara hated to be rude, but there seemed no help for it.

The striking of a quarter past ten improved his chances. It had been privily agreed upon beforehand amongst the members of the class that at a quarter past ten every one was to sneeze simultaneously. The noise startled Mr. Banks considerably. The angelic mood began to wear off. A man may be long-suffering, but he likes to draw the line somewhere.

“Another exhibition like that,” he said, sharply, “and the class stays in after school. O’Hara!”

“Sir?”

“Silence.”

“I said nothing, sir, really.”

“Boy, you made a cat-like noise with your mouth.”

“What sort of noise, sir?”

The form waited breathlessly. This peculiarly insidious question had been invented for mathematical use by one Sandys, who had left at the end of the previous summer. It was but rarely that the master increased the gaiety of nations by answering the question in the manner desired.

Mr. Banks, off his guard, fell into the trap.

“A noise like this,” he said curtly, and to the delighted audience came the melodious sound of a “Mi-aou,” which put O’Hara’s effort completely in the shade, and would have challenged comparison with the war-cry of the stoutest mouser that ever trod a tile.

A storm of imitations arose from all parts of the room. Mr. Banks turned pink, and, going straight to the root of the disturbance, forthwith evicted O’Hara.

O’Hara left with the satisfying feeling that his duty had been done.

Mr. Banks’ room was at the top of the middle block. He ran softly down the stairs at his best pace. It was not likely that the master would come out into the passage to see if he was still there, but it might happen, and it would be best to run as few risks as possible.

He sprinted over to the junior block, raised the trap-door, and jumped down. He knew where the ferrets had been placed, and had no difficulty in finding them. In another minute he was in the passage again, with the trap-door bolted behind him.

He now asked himself—what should he do with them? He must find a safe place, or his labours would have been in vain.

Behind the fives-court, he thought, would be the spot. Nobody ever went there. It meant a run of three hundred yards there and the same distance back, and there was more than a chance that he might be seen by one of the Powers. In which case he might find it rather hard to explain what he was doing in the middle of the grounds with a couple of ferrets in his possession when the hands of the clock pointed to twenty minutes to eleven.

But the odds were against his being seen. He risked it.

When the bell rang for the quarter to eleven interval the ferrets were in their new home, happily discussing a piece of meat—Renford’s contribution, held over from the morning’s meal,—and O’Hara, looking as if he had never left the passage for an instant, was making his way through the departing mathematical class to apologise handsomely to Mr. Banks—as was his invariable custom—for his disgraceful behaviour during the morning’s lesson.

CHAPTER XIX.

The Mayor’s Visit.

CHOOL

prefects at Wrykyn did weekly essays for the headmaster. Those who had

got their scholarships at the ’Varsity or who were going up in the following

year used to take their essays to him after school and read them to him—an

unpopular and nerve-destroying practice, akin to suicide. Trevor had got

his scholarship in the previous November. He was due at the headmaster’s

private house at six o’clock on the present Tuesday. He was looking

forward to the ordeal not without apprehension. The essay subject this

week had been “One man’s meat is another man’s poison,” and Clowes, whose idea

of English Essay was that it should be a medium for intemperate

frivolity, had insisted on his beginning with, “While I cannot conscientiously

go so far as to say that one man’s meat is another man’s poison, yet I am

certainly of opinion that what is highly beneficial to one man may, on the

other hand, to another man, differently constituted, be extremely deleterious,

and, indeed, absolutely fatal.”

CHOOL

prefects at Wrykyn did weekly essays for the headmaster. Those who had

got their scholarships at the ’Varsity or who were going up in the following

year used to take their essays to him after school and read them to him—an

unpopular and nerve-destroying practice, akin to suicide. Trevor had got

his scholarship in the previous November. He was due at the headmaster’s

private house at six o’clock on the present Tuesday. He was looking

forward to the ordeal not without apprehension. The essay subject this

week had been “One man’s meat is another man’s poison,” and Clowes, whose idea

of English Essay was that it should be a medium for intemperate

frivolity, had insisted on his beginning with, “While I cannot conscientiously

go so far as to say that one man’s meat is another man’s poison, yet I am

certainly of opinion that what is highly beneficial to one man may, on the

other hand, to another man, differently constituted, be extremely deleterious,

and, indeed, absolutely fatal.”

Trevor was not at all sure how the headmaster would take it. But Clowes had seemed so cut up at his suggestion that it had better be omitted, that he had allowed it to stand.

He was putting the final polish on this gem of English literature at half-past five, when Milton came in.

“Busy?” said Milton.

Trevor said he would be through in a minute.

Milton took a chair, and waited.

Trevor scratched out two words and substituted two others, made a couple of picturesque blots, and, laying down his pen, announced that he had finished.

“What’s up?” he said.

“It’s about the League,” said Milton.

“Found out anything?”

“Not anything much. But I’ve been making inquiries. You remember I asked you to let me look at those letters of yours?”

Trevor nodded. This had happened on the Sunday of that week.

“Well, I wanted to look at the post-marks.”

“By Jove, I never thought of that.”

Milton continued with the business-like air of the detective who explains how he did it in the last chapter of the book.

“I found, as I thought, that both letters came from the same place.”

Trevor pulled out the letters in question.

“So they do,” he said, “Chesterton.”

“Do you know Chesterton?” asked Milton.

“Only by name.”

“It’s a small hamlet about two miles from here across the downs. There’s only one shop in the place, which acts as post-office and tobacconist and everything else. I thought that if I went there and asked about those letters, they might remember who it was that sent them, if I showed them a photograph.”

“By Jove,” said Trevor, “of course! Did you? What happened?”

“I went there yesterday afternoon. I took about half-a-dozen photographs of various chaps, including Rand-Brown.”

“But wait a bit. If Chesterton’s two miles off, Rand-Brown couldn’t have sent the letters. He wouldn’t have the time after school. He was on the grounds both the afternoons before I got the letters.”

“I know,” said Milton; “I didn’t think of that at the time.”

“Well?”

“One of the points about the Chesterton post-office is that there’s no letter-box outside. You have to go into the shop and hand anything you want to post across the counter. I thought this was a tremendous score for me. I thought they would be bound to remember who handed in the letters. There can’t be many at a place like that.”

“Did they remember?”

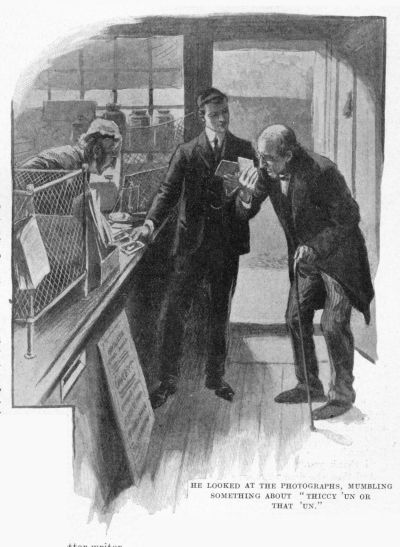

“They remembered the letters being given in distinctly, but as for knowing anything beyond that, they were simply futile. There was an old woman in the shop, aged about three hundred and ten, I should think. I shouldn’t say she had ever been very intelligent, but now she simply gibbered. I started off by laying out a shilling on some poisonous-looking sweets. I gave the lot to a village kid when I got out. I hope they didn’t kill him. Then, having scattered ground-bait in that way, I lugged out the photographs, mentioned the letters and the date they had been sent, and asked her to weigh in and identify the sender.”

“Did she?”

“My dear chap, she identified them all, one after the other. The first was one of Clowes. She was prepared to swear on oath that that was the chap who had sent the letters. Then I shot a photograph of you across the counter, and doubts began to creep in. She said she was certain it was one of those two ‘la-ads’, but couldn’t quite say which. To keep her amused I fired in photograph number three—Allardyce’s. She identified that, too. At the end of ten minutes she was pretty sure that it was one of the six—the other three were Paget, Clephane, and Rand-Brown—but she was not going to bind herself down to any particular one. As I had come to the end of my stock of photographs, and was getting a bit sick of the game, I got up to go, when in came another ornament of Chesterton from a room at the back of the shop. He was quite a kid, not more than a hundred and fifty at the outside, so, as a last chance, I tackled him on the subject. He looked at the photographs for about half an hour, mumbling something about it not being ‘thiccy ’un’ or ‘that ’un,’ or ‘that ’ere tother’un,’ until I began to feel I’d had enough of it. Then it came out that the real chap who had sent the letters was a ‘la-ad’ with light hair, not so big as me——”

“That doesn’t help us much,” said Trevor.

“—And a ‘prarper little gennlemun.’ So all we’ve got to do is to look for some young duke of polished manners and exterior, with a thatch of light hair.”

“There are three hundred and sixty-seven fellows with light hair in the school,” said Trevor, calmly.

“Thought it was three hundred and sixty-eight myself,” said Milton, “but I may be wrong. Anyhow, there you have the results of my investigations. If you can make anything out of them, you’re welcome to it. Good-bye.”

“Half a second,” said Trevor, as he got up; “had the fellow a cap of any sort?”

“No. Bare-headed. You wouldn’t expect him to give himself away by wearing a house-cap?”

Trevor went over to the headmaster’s revolving this discovery in his mind. It was not much of a clue, but the smallest clue is better than nothing. To find out that the sender of the League letters had fair hair narrowed the search down a little. It cleared the more raven-locked members of the school, at any rate. Besides, by combining his information with Milton’s, the search might be still further narrowed down. He knew that the polite letter-writer must be either in Seymour’s or in Donaldson’s. The number of fair-haired youths in the two houses was not excessive. Indeed, at the moment he could not recall any, which rather complicated matters.

He arrived at the headmaster’s door, and knocked. He was shown into a room at the side of the hall, near the door. The butler informed him that the head-master was engaged at present. Trevor, who knew the butler slightly through having constantly been to see the head-master on business viâ the front door, asked who was there.

“Sir Eustace Briggs,” said the butler, and disappeared in the direction of his lair beyond the green baize partition at the end of the hall.

Trevor went into the room, which was a sort of spare study, and sat down, wondering what had brought the mayor of Wrykyn to see the head-master at this advanced hour.

A quarter of an hour later the sound of voices broke in upon his peace. The head-master was coming down the hall with the intention of showing his visitor out. The door of Trevor’s room was ajar, and he could hear distinctly what was being said. He had no particular desire to play the eavesdropper, but the part was forced upon him.

Sir Eustace seemed excited.

“It is far from being my habit,” he was saying, “to make unnecessary complaints respecting the conduct of the lads under your care.” (Sir Eustace Briggs had a distaste for the shorter and more colloquial forms of speech. He would have perished sooner than have substituted “complain of your boys” for the majestic formula he had used. He spoke as if he enjoyed choosing his words. He seemed to pause and think before each word. Unkind people—who were jealous of his distinguished career—used to say that he did this because he was afraid of dropping an aitch if he relaxed his vigilance.)

“But,” continued he, “I am reluctantly forced to the unpleasant conclusion that the dastardly outrage to which both I and the Press of the town have called your attention is to be attributed to one of the lads to whom I ’ave—have (this with a jerk) referred.”

“I will make a thorough inquiry, Sir Eustace,” said the bass voice of the head-master.

“I thank you,” said the mayor. “It would, under the circumstances, be nothing more, I think, than what is distinctly advisable. The man Samuel Wapshott, of whose narrative I have recently afforded you a brief synopsis, stated in no uncertain terms that he found at the foot of the statue on which the dastardly outrage was perpetrated a diminutive ornament, in shape like the bats that are used in the game of cricket. This ornament, he avers (with what truth I know not), was handed by him to a youth of an age coëval with that of the lads in the upper division of this school. The youth claimed it as his property, I was given to understand.”

“A thorough inquiry shall be made, Sir Eustace.”

“I thank you.”

And then the door shut, and the conversation ceased.

CHAPTER XX.

The Finding of the Bat.

REVOR

waited till the headmaster had gone back to his library, gave him five minutes

to settle down, and then went in.

REVOR

waited till the headmaster had gone back to his library, gave him five minutes

to settle down, and then went in.

The head-master looked up inquiringly.

“My essay, sir,” said Trevor.

“Ah, yes. I had forgotten.”

Trevor opened the note-book and began to read what he had written. He finished the paragraph which owed its insertion to Clowes, and raced hurriedly on to the next. To his surprise the flippancy passed unnoticed, at any rate, verbally. As a rule the head-master preferred that quotations from back numbers of Punch should be kept out of the prefects’ English Essays. And he generally said as much. But to-day he seemed strangely preoccupied. A split infinitive in paragraph five, which at other times would have made him sit up in his chair stiff with horror, elicited no remark. The same immunity was accorded to the insertion (inspired by Clowes, as usual) of a popular catch phrase in the last few lines. Trevor finished with the feeling that luck had favoured him nobly.

“Yes,” said the head-master, seemingly roused by the silence following on the conclusion of the essay. “Yes.” Then, after a long pause, “Yes,” again.

Trevor said nothing, but waited for further comment.

“Yes,” said the head-master once more, “I think that is a very fair essay. Very fair. It wants a little more—er—not quite so much—um—yes.”

Trevor made a note in his mind to effect these improvements in future essays, and was getting up, when the head-master stopped him.

“Don’t go, Trevor. I wish to speak to you.”

Trevor’s first thought was, perhaps naturally, that the bat was going to be brought into discussion. He was wondering helplessly how he was going to keep O’Hara and his midnight exploit out of the conversation, when the head-master resumed. “An unpleasant thing has happened, Trevor——”

“Now we’re coming to it,” thought Trevor.

“It appears, Trevor, that a considerable amount of smoking has been going on in the school.”

Trevor breathed freely once more. It was only going to be a mere conventional smoking row after all. He listened with more enjoyment as the head-master, having stopped to turn down the wick of the reading-lamp which stood on the table at his side, and which had begun, appropriately enough, to smoke, resumed his discourse.

“Mr. Dexter——”

Of course, thought Trevor. If there ever was a row in the school, Dexter was bound to be at the bottom of it.

“Mr. Dexter has just been in to see me. He reported six boys. He discovered them in the vault beneath the junior block. Two of them were boys in your house.”

Trevor murmured something wordless, to show that the story interested him.

“You knew nothing of this, of course——”

“No, sir.”

“No. Of course not. It is difficult for the head of a house to know all that goes on in that house.”

Was this his beastly sarcasm? Trevor asked himself. But he came to the conclusion that it was not. After all, the head of a house is only human. He cannot be expected to keep an eye on the private life of every member of his house.

“This must be stopped, Trevor. There is no saying how widespread the practice has become or may become. What I want you to do is to go straight back to your house and begin a complete search of the studies.”

“To-night, sir?” It seemed too late for such amusement.

“To-night. But before you go to your house, call at Mr. Seymour’s, and tell Milton I should like to see him. And, Trevor.”

“Yes, sir?”

“You will understand that I am leaving this matter to you to be dealt with by you. I shall not require you to make any report to me. But if you should find tobacco in any boy’s room, you must punish him well, Trevor. Punish him well.”

This meant that the culprit must be “touched up” before the house assembled in the dining-room. Such an event did not often occur. The last occasion had been in Paget’s first term as head of Donaldson’s, when two of the senior day-room had been discovered attempting to revive the ancient and dishonourable custom of bullying. This time, Trevor foresaw, would set up a record in all probability. There might be any number of devotees of the weed, and he meant to carry out his instructions to the full, and make the criminals more unhappy than they had been since the day of their first cigar. Trevor hated the habit of smoking at school. He was so intensely keen on the success of the house and the school at games, that anything which tended to damage the wind and eye filled him with loathing. That anybody should dare to smoke in a house which was going to play in the final for the House Football Cup made him rage internally, and he proposed to make things bad and unrestful for such.

To smoke at school is to insult the divine weed. When you are obliged to smoke in odd corners, fearing every moment that you will be discovered, the whole meaning, poetry, romance of a pipe vanishes, and you become like those lost beings who smoke when they are running to catch trains. The boy who smokes at school is bound to come to a bad end. He will degenerate gradually into a person that plays dominoes in the smoking rooms of tea shops with friends who wear bowler hats and frock coats.

Much of this philosophy Trevor expounded to Clowes in energetic language when he returned to Donaldson’s after calling at Seymour’s to deliver the message for Milton.

Clowes became quite animated at the prospect of a real row.

“We shall be able to see the skeletons in their cupboards,” he observed. “Every man has a skeleton in his cupboard, which follows him about wherever he goes. Which study shall we go to first?”

“We?” said Trevor.

“We,” repeated Clowes firmly. “I am not going to be left out of this jaunt. I need bracing up—I’m not strong, you know—and this is just the thing to do it. Besides, you’ll want a bodyguard of some sort, in case the infuriated occupant turns and rends you.”

“I don’t see what there is to enjoy in the business,” said Trevor, gloomily. “Personally, I bar this kind of thing. By the time we’ve finished, there won’t be a chap in the house I’m on speaking terms with.”

“Except me, dearest,” said Clowes. “I will never desert you. It’s of no use asking me, for I will never do it. Mr. Micawber has his faults, but I will never desert Mr. Micawber.”

“You can come if you like,” said Trevor; “we’ll take the studies in order. I suppose we needn’t look up the prefects?”

“A prefect is above suspicion. Scratch the prefects.”

“That brings us to Dixon.”

Dixon was a stout youth with spectacles, who was popularly supposed to do twenty-two hours’ work a day. It was believed that he put in two hours sleep from eleven to one, and then got up and worked in his study till breakfast.

He was working when Clowes and Trevor came in. He dived head foremost into a huge Liddell and Scott as the door opened. On hearing Trevor’s voice he slowly emerged, and a pair of round and spectacled eyes gazed blankly at the visitors. Trevor briefly explained his errand, but the interview lost in solemnity owing to the fact that the bare notion of Dixon storing tobacco in his room made Clowes roar with laughter. Also, Dixon stolidly refused to understand what Trevor was talking about, and at the end of ten minutes, finding it hopeless to try and explain, the two went. Dixon, with a hazy impression that he had been asked to join in some sort of round game, and had refused the offer, returned again to his Liddell and Scott, and continued to wrestle with the somewhat obscure utterances of the chorus in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. The results of this fiasco on Trevor and Clowes were widely different. Trevor it depressed horribly. It made him feel savage. Clowes, on the other hand, regarded the whole affair in a spirit of rollicking farce, and refused to see that this was a serious matter, in which the honour of the house was involved.

The next study was Ruthven’s. This fact somewhat toned down the exuberances of Clowes’s demeanour. When one particularly dislikes a person, one has a curious objection to seeming in good spirits in his presence. One feels that he may take it as a sort of compliment to himself, or, at any rate, contribute grins of his own, which would be hateful. Clowes was as grave as Trevor when they entered the study.

Ruthven’s study was like himself, overdressed and rather futile. It ran to little china ornaments in a good deal of profusion. It was more like a drawing-room than a school study.

“Sorry to disturb you, Ruthven,” said Trevor.

“Oh, come in,” said Ruthven, in a tired voice. “Please shut the door; there is a draught. Do you want anything?”

“We’ve got to have a look round,” said Clowes.

“Can’t you see everything there is?”

Ruthven hated Clowes as much as Clowes hated him.

Trevor cut into the conversation again.

“It’s like this, Ruthven,” he said. “I’m awfully sorry, but the old man’s just told me to search the studies in case any of the fellows have got baccy.”

Ruthven jumped up, pale with consternation.

“You can’t. I won’t have you disturbing my study.”

“This is rot,” said Trevor, shortly, “I’ve got to. It’s no good making it more unpleasant for me than it is.”

“But I’ve no tobacco. I swear I haven’t.”

“Then why mind us searching?” said Clowes affably.

“Come on, Ruthven,” said Trevor, “chuck us over the keys. You might as well.”

“I won’t.”

“Don’t be an ass, man.”

“We have here,” observed Clowes, in his sad, solemn way, “a stout and serviceable poker.” He stooped, as he spoke, to pick it up.

“Leave that poker alone,” cried Ruthven.

Clowes straightened himself.

“I’ll swop it for your keys,” he said.

“Don’t be a fool.”

“Very well, then. We will now crack our first crib.”

Ruthven sprang forward, but Clowes, handing him off in football fashion with his left hand, with his right dashed the poker against the lock of the drawer of the table by which he stood.

The lock broke with a sharp crack. It was not built with an eye to such onslaught.

“Neat for a first shot,” said Clowes, complacently. “Now for the Umustaphas and shag.”

But as he looked into the drawer he uttered a sudden cry of excitement. He drew something out, and tossed it over to Trevor.

“Catch, Trevor,” he said quietly. “Something that’ll interest you.”

Trevor caught it neatly in one hand, and stood staring at it as if he had never seen anything like it before. And yet he had—often. For what he had caught was a little golden bat, about an inch long by an eighth of an inch wide.

(To be concluded.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums