The Captain, March 1905

CHAPTER XXI.

in which an episode is closed.

HANKS,”

said Fenn.

HANKS,”

said Fenn.

He stood twirling the cap round in his hand as Spencer closed the door. Then he threw it on to the table. He did not feel particularly disturbed at the thought of the interview that was to come. He had been expecting the cap to turn up, like the corpse of Eugene Aram’s victim, at some inconvenient moment. It was a pity that it had come just as things looked as if they might be made more or less tolerable in Kay’s. He had been looking forward with a grim pleasure to the sensation that would be caused in the house when it became known that he and Kennedy had formed a combine for its moral and physical benefit. But that was all over. He would be sacked, beyond a doubt. In the history of Eckleton, as far as he knew it, there had never been a case of a fellow breaking out at night and not being expelled when he was caught. It was one of the cardinal sins in the school code. There had been the case of Peter Brown, which his brother had mentioned in his letter. And in his own time he had seen three men vanish from Eckleton for the same offence. He did not flatter himself that his record at the school was so good as to make it likely that the authorities would stretch a point in his favour.

“So long, Kennedy,” he said. “You’ll be here when I get back, I suppose?”

“What does he want you for, do you think?” asked Kennedy, stretching himself, with a yawn. It never struck him that Fenn could be in any serious trouble. Fenn was a prefect; and when the headmaster sent for a prefect, it was generally to tell him that he had got a split infinitive in his English Essay that week.

“Glad I’m not you,” he added, as a gust of wind rattled the sash, and the rain dashed against the pane. “Beastly evening to have to go out.”

“It isn’t the rain I mind,” said Fenn; “it’s what’s going to happen when I get indoors again,” and refused to explain further. There would be plenty of time to tell Kennedy the whole story when he returned. It was better not to keep the headmaster waiting.

The first thing he noticed on reaching the School House was the strange demeanour of the butler. Whenever Fenn had had occasion to call on the headmaster hitherto, Watson had admitted him with the air of a high priest leading a devotee to a shrine of which he was the sole managing director. This evening he seemed restless, excited.

“Good evening, Mr. Fenn,” he said. “This way, sir.”

Those were his actual words. Fenn had not known for certain until now that he could talk. On previous occasions their conversations had been limited to an “Is the headmaster in?” from Fenn, and a stately inclination of the head from Watson. The man was getting a positive babbler.

With an eager, springy step, distantly reminiscent of a shopwalker heading a procession of customers, with a touch of the style of the winner in a walking-race to Brighton, the once slow-moving butler led the way to the headmaster’s study.

For the first time since he started out, Fenn was conscious of a tremor. There is something about a closed door, behind which somebody is waiting to receive one, which appeals to the imagination, especially if the ensuing meeting is likely to be an unpleasant one.

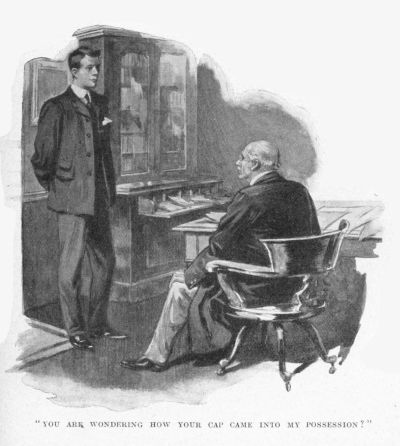

“Ah, Fenn,” said the headmaster. “Come in.”

Fenn wondered. It was not in this tone of voice that the Head was wont to begin a conversation which was going to prove painful.

“You’ve got your cap, Fenn? I gave it to a small boy in your house to take to you.”

“Yes, sir.”

He had given up all hope of understanding the Head’s line of action. Unless he was playing a deep game, and intended to flash out suddenly with a keen question which it would be impossible to parry, there seemed nothing to account for the strange absence of anything unusual in his manner. He referred to the cap as if he had borrowed it from Fenn, and had returned it by bearer, hoping that its loss had not inconvenienced him at all.

“I daresay,” continued the Head, “that you are wondering how it came into my possession. You missed it, of course?”

“Very much, sir,” said Fenn, with perfect truth.

“It has just been brought to my house, together with a great many other things, more valuable, perhaps,”—here he smiled a head-magisterial smile—“by a policeman from Eckleton.”

Fenn was still unequal to the intellectual pressure of the conversation. He could understand, in a vague way, that for some unexplained reason things were going well for him, but beyond that his mind was in a whirl.

“You will remember the unfortunate burglary of Mr. Kay’s house and mine. Your cap was returned with the rest of the stolen property.”

Just so, thought Fenn. The rest of the stolen property? Exactly. Go on. Don’t mind me. I shall begin to understand soon, I suppose.

He condensed these thoughts into the verbal reply, “Yes, sir.”

“I sent for you to identify your own property. I see there is a silver cup belonging to you. Perhaps there are also other articles. Go and see. You will find them on that table. They are in a hopeless state of confusion, having been conveyed here in a sack. Fortunately, nothing is broken.”

He was thinking of certain valuables belonging to himself which had been abstracted from his drawing-room on the occasion of the burglar’s visit to the School House.

Fenn crossed the room, and began to inspect the table indicated. On it was as mixed a collection of valuable and useless articles as one could wish to see. He saw his cup at once, and attached himself to it. But of all the other exhibits in this private collection, he could recognise nothing else as his property.

“There is nothing of mine here except the cup, sir,” he said.

“Ah. Then that is all, I think. You are going back to Mr. Kay’s? Then please send Kennedy to me. Good-night, Fenn.”

“Good-night, sir.”

Even now Fenn could not understand it. The more he thought it over the more his brain reeled. He could grasp the fact that his cap and his cup were safe again, and that there was evidently going to be no sacking for the moment. But how it had all happened, and how the police had got hold of his cap, and why they had returned it with the loot gathered in by the burglar who had visited Kay’s and the School House, were problems which, he had to confess, were beyond him.

He walked to Kay’s through the rain with the cup under his mackintosh, and freely admitted to himself that there were things in heaven and earth—and particularly earth—which no fellow could understand.

“I don’t know,” he said, when Kennedy pressed for an explanation of the reappearance of the cup. “It’s no good asking me. I’m going now to borrow the matron’s smelling-salts: I feel faint. After that I shall wrap a wet towel round my head, and begin to think it out. Meanwhile, you’re to go over to the Head. He’s had enough of me, and he wants to have a look at you.”

“Me?” said Kennedy. “Why?”

“Now, is it any good asking me?” said Fenn. “If you can find out what it’s all about, I’ll thank you if you’ll come and tell me.”

Ten minutes later Kennedy returned. He carried a watch and chain.

“I couldn’t think what had happened to my watch,” he said. “I missed it on the day after that burglary here, but I never thought of thinking it had been collared by a professional. I thought I must have lost it somewhere.”

“Well, have you grasped what’s been happening?”

“I’ve grasped my ticker, which is good enough for me. Half a second. The old man wants to see the rest of the prefects. He’s going to work through the house in batches, instead of man by man. I’ll just go round the studies and rout them out, and then I’ll come back and explain. It’s perfectly simple.”

“Glad you think so,” said Fenn.

Kennedy went and returned.

“Now,” he said, subsiding into a deck-chair, “what is it you don’t understand?”

“I don’t understand anything. Begin at the beginning.”

“I got the yarn from the butler—what’s his name?”

“Those who know him well enough to venture to give him a name—I’ve never dared to myself—call him Watson,” said Fenn.

“I got the yarn from Watson. He was as excited as anything about it. I never saw him like that before.”

“I noticed something queer about him.”

“He’s awfully bucked, and is doing the Ancient Mariner business all over the place. Wants to tell the story to everyone he sees.”

“Well, suppose you follow his example. I want to hear about it.”

“Well, it seems that the police have been watching a house at the corner of the High-street for some time—what’s up?”

“Nothing. Go on.”

“But you said, ‘By Jove!’ ”

“Well, why shouldn’t I say ‘By Jove’? When you are telling sensational yarns, it’s my duty to say something of the sort. Buck along.”

“It’s a house not far from the Town Hall, at the corner of Pegwell-street—you’ve probably been there scores of times.”

“Once or twice, perhaps,” said Fenn. “Well?”

“About a month ago two suspicious-looking bounders went to live there. Watson says their faces were enough to hang them. Anyhow, they must have been pretty bad, for they made even the Eckleton police, who are pretty average-sized rotters, suspicious, and they kept an eye on them. Well, after a bit there began to be a regular epidemic of burglary round about here. Watson says half the houses round were broken into. The police thought it was getting a bit too thick, but they didn’t like to raid the house without some jolly good evidence that these two men were the burglars, so they lay low and waited till they should give them a decent excuse for jumping on them. They had had a detective chap down from London, by the way, to see if he couldn’t do something about the burglaries, and he kept his eye on them, too.”

“They had quite a gallery. Didn’t they notice any of the eyes?”

“No. Then after a bit one of them nipped off to London with a big bag. The detective chap was after him like a shot. He followed him from the station, saw him get into a cab, got into another himself, and stuck to him hard. The front cab stopped at about a dozen pawnbrokers’ shops. The detective Johnny took the names and addresses, and hung on to the burglar man all day, and finally saw him return to the station, where he caught a train back to Eckleton. Directly he had seen him off, the detective got into a cab, called on the dozen pawnbrokers, showed his card, with ‘Scotland Yard’ on it, I suppose, and asked to see what the other chap had pawned. He identified every single thing as something that had been collared from one of the houses round Eckleton way. So he came back here, told the police, and they raided the house, and there they found stacks of loot of all descriptions.”

“Including my cap,” said Fenn, thoughtfully. “I see now.”

“Rummy the man thinking it worth his while to take an old cap,” said Kennedy.

“Very,” said Fenn. “But it’s been a rum business all along.”

CHAPTER XXII.

kay’s changes its name.

OR

the remaining weeks of the winter term, things went as smoothly in Kay’s as Kay

would let them. That restless gentleman still continued to burst in on Kennedy

from time to time with some sensational story of how he had found a fag doing

what he ought not to have done. But there was a world of difference between the

effect these visits had now and that which they had had when Kennedy had stood

alone in the house, his hand against all men. Now that he could work off the

effects of such encounters by going straight to Fenn’s study and picking the house-master

to pieces, the latter’s peculiar methods ceased to be irritating, and became

funny. Mr. Kay was always ferreting out the weirdest misdoings on the part of

the members of his house, and rushing to Kennedy’s study to tell him about them

at full length, like a rather indignant dog bringing a rat he has hunted down

into a drawing-room, to display it to the company. On one occasion, when Fenn

and Jimmy Silver were in Kennedy’s study, Mr. Kay dashed in to complain bitterly

that he had discovered that the junior day-room kept mice in their lockers.

Apparently this fact seemed to him enough to cause an epidemic of typhoid fever

in the place, and he hauled Kennedy over the coals, in a speech that lasted

five minutes, for not having detected this plague-spot in the house.

OR

the remaining weeks of the winter term, things went as smoothly in Kay’s as Kay

would let them. That restless gentleman still continued to burst in on Kennedy

from time to time with some sensational story of how he had found a fag doing

what he ought not to have done. But there was a world of difference between the

effect these visits had now and that which they had had when Kennedy had stood

alone in the house, his hand against all men. Now that he could work off the

effects of such encounters by going straight to Fenn’s study and picking the house-master

to pieces, the latter’s peculiar methods ceased to be irritating, and became

funny. Mr. Kay was always ferreting out the weirdest misdoings on the part of

the members of his house, and rushing to Kennedy’s study to tell him about them

at full length, like a rather indignant dog bringing a rat he has hunted down

into a drawing-room, to display it to the company. On one occasion, when Fenn

and Jimmy Silver were in Kennedy’s study, Mr. Kay dashed in to complain bitterly

that he had discovered that the junior day-room kept mice in their lockers.

Apparently this fact seemed to him enough to cause an epidemic of typhoid fever

in the place, and he hauled Kennedy over the coals, in a speech that lasted

five minutes, for not having detected this plague-spot in the house.

“So that’s the celebrity at home, is it?” said Jimmy Silver, when he had gone. “I now begin to understand more or less why this house wants a new Head every two terms. Is he often taken like that?”

“He’s never anything else,” said Kennedy. “Fenn keeps a list of the things he rags me about, and we have an even shilling on, each week, that he will beat the record of the previous week. At first I used to get the shilling if he lowered the record; but after a bit it struck us that it wasn’t fair, so now we take it on alternate weeks. This is my week, by the way. I think I can trouble you for that bob, Fenn?”

“I wish I could make it more,” said Fenn, handing over the shilling.

“What sort of things does he rag you about generally?” inquired Silver.

Fenn produced a slip of paper.

“Here are a few,” he said, “for this month. He came in on the 10th because he found two kids fighting. Kennedy was down town when it happened, but that made no difference. Then he caught the senior dayroom making a row of some sort. He said it was perfectly deafening; but we couldn’t hear it in our studies. I believe he goes round the house, listening at keyholes. That was on the 16th. On the 22nd he found a chap in Kennedy’s dormitory wandering about the house at one in the morning. He seemed to think that Kennedy ought to have sat up all night on the chance of somebody cutting out of the dormitory. At any rate, he ragged him. I won the weekly shilling on that; and deserved it, too.”

Fenn had to go over to the gymnasium shortly after this. Jimmy Silver stayed on, talking to Kennedy.

“And bar Kay,” said Jimmy, “how do you find the house doing? Any better?”

“Better! It’s getting a sort of model establishment. I believe, if we keep pegging away at them, we may win some sort of a cup sooner or later.”

“Well, Kay’s very nearly won the cricket cup last year. You ought to get it next season, now that you and Fenn are both in the team.”

“Oh, I don’t know. It’ll be a fluke if we do. Still, we’re hoping. It isn’t every house that’s got a county man in it. But we’re breaking out in another place. Don’t let it get about, for goodness’ sake, but we’re going for the sports’ cup.”

“Hope you’ll get it. Blackburn’s won’t have a chance, anyhow, and I should like to see somebody get it away from the School House. They’ve had it much too long. They’re beginning to look on it as their right. But who are your men?”

“Well, Fenn ought to be a cert for the hundred and the quarter, to start with.”

“But the School House must get the long run, and the mile, and the half, too, probably.”

“Yes. We haven’t anyone to beat Milligan, certainly. But there are the second and third places. Don’t forget those. That’s where we’re going to have a look in. There’s all sorts of unsuspected talent in Kay’s. To look at Peel, for instance, you wouldn’t think he could do the hundred in eleven, would you? Well, he can, only he’s been too slack to go in for the race at the sports, because it meant training. I had him up here and reasoned with him, and he’s promised to do his best. Eleven is good enough for second place in the hundred, don’t you think? There are lots of others in the house who can do quite decently on the track, if they try. I’ve been making strict inquiries. Kay’s are hot stuff, Jimmy. Heap big medicine. That’s what they are.”

“You’re a wonderful man, Kennedy,” said Jimmy Silver. And he meant it. Kennedy’s uphill fight at Kay’s had appealed to him strongly. He himself had never known what it meant to have to manage a hostile house. He had stepped into his predecessor’s shoes at Blackburn’s much as the heir to a throne becomes king. Nobody had thought of disputing his right to the place. He was next man in; so, directly the departure of the previous head of Blackburn’s left a vacancy, he stepped into it, and the machinery of the house had gone on as smoothly as if there had been no change at all. But Kennedy had gone in against a slack and antagonistic house, with weak prefects to help him, and a fussy housemaster; and he had fought them all for a term, and looked like winning. Jimmy admired his friend with a fervour which nothing on earth would have tempted him to reveal. Like most people with a sense of humour, he had a fear of appearing ridiculous, and he hid his real feelings as completely as he was able.

“How is the footer getting on?” inquired Jimmy, remembering the difficulties Kennedy had encountered earlier in the term in connection with his house team.

“It’s better,” said Kennedy. “Keener, at any rate. We shall do our best in the house matches. But we aren’t a good team.”

“Any more trouble about your being captain instead of Fenn?”

“No. We both sign the lists now. Fenn didn’t want to, but I thought it would be a good idea, so we tried it. It seems to have worked all right.”

“Of course, your getting your first has probably made a difference.”

“A bit, perhaps.”

“Well, I hope you won’t get the footer cup, because I want it for Blackburn’s. Or the cricket cup. I want that, too. But you can have the sports’ cup with my blessing.”

“Thanks,” said Kennedy. “It’s very generous of you.”

“Don’t mention it,” said Jimmy.

From which conversation it will be seen that Kay’s was gradually pulling itself together. It had been asleep for years. It was now waking up.

When the winter term ended there were distinct symptoms of an outbreak of public spirit in the house.

The Easter term opened auspiciously in one way. Neither Walton nor Perry returned. The former had been snapped up in the middle of the holidays—to his enormous disgust—by a bank, which wanted his services so much that it was prepared to pay him 40 pounds a year simply to enter the addresses of its outgoing letters in a book, and post them when he had completed this ceremony. After a spell of this he might hope to be transferred to another sphere of bank life and thought, and at the end of his first year he might even hope for a rise in his salary of ten pounds, if his conduct was good, and he had not been late on more than twenty mornings in the year. I am aware that in a properly-regulated story of school-life Walton would have gone to the Eckleton races, returned in a state of speechless intoxication, and been summarily expelled; but facts are facts, and must not be tampered with. The ingenious but not industrious Perry had been superannuated. For three years he had been in the Lower Fourth. Probably the master of that form went to the Head, and said that his constitution would not stand another year of him, and that either he or Perry must go. So Perry had departed. Like a poor play, he had “failed to attract,” and was withdrawn. There was also another departure of an even more momentous nature.

Mr. Kay had left Eckleton.

Kennedy was no longer head of Kay’s. He was now head of Dencroft’s.

Mr. Dencroft was one of the most popular masters in the school. He was a keen athlete and a tactful master. Fenn and Kennedy knew him well, through having played at the nets and in scratch games with him. They both liked him. If Kennedy had had to select a housemaster, he would have chosen Mr. Blackburn first. But Mr. Dencroft would have been easily second.

Fenn learned the facts from the matron, and detailed them to Kennedy.

“Kay got the offer of a headmastership at a small school in the north, and jumped at it. I pity the fellows there. They are going to have a lively time.”

“I’m jolly glad Dencroft has got the house,” said Kennedy. “We might have had some awful rotter put in. Dencroft will help us buck up the house games.”

The new housemaster sent for Kennedy on the first evening of term. He wished to find out how the Head of the house and the ex-Head stood with regard to one another. He knew the circumstances, and comprehended vaguely that there had been trouble.

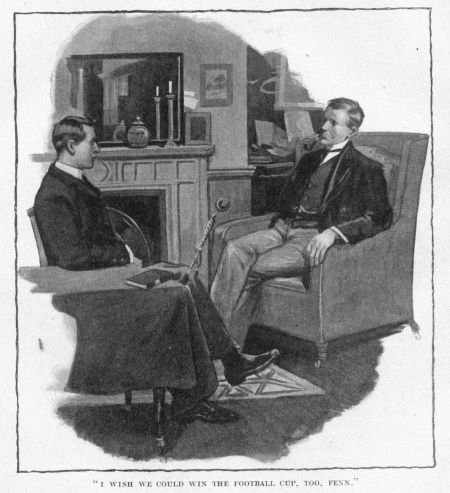

“I hope we shall have a good term,” he said.

“I hope so, sir,” said Kennedy.

“You—er—you think the house is keener, Kennedy, than when you first came in?”

“Yes, sir. They are getting quite keen now. We might win the sports.”

“I hope we shall. I wish we could win the football cup, too, but I am afraid Mr. Blackburn’s are very heavy metal.”

“It’s hardly likely we shall have very much chance with them; but we might get into the final!”

“It would be an excellent thing for the house if we could. I hope Fenn is helping you get the team into shape?” he added.

“Oh, yes, sir,” said Kennedy. “We share the captaincy. We both sign the lists.”

“A very good idea,” said Mr. Dencroft, relieved. “Good-night, Kennedy.”

“Good-night, sir,” said Kennedy.

CHAPTER XXIII.

the house matches.

HE

chances of Kay’s in the inter-house Football Competition were not thought very

much of by their rivals. Of late years each of the other houses had prayed to

draw Kay’s for the first round, it being a certainty that this would mean that

they got at least into the second round, and so a step nearer the cup. Nobody,

however weak compared to Blackburn’s, which was at the moment the crack

football house, ever doubted the result of a match with Kay’s. It was looked on

as a sort of gentle trial trip.

HE

chances of Kay’s in the inter-house Football Competition were not thought very

much of by their rivals. Of late years each of the other houses had prayed to

draw Kay’s for the first round, it being a certainty that this would mean that

they got at least into the second round, and so a step nearer the cup. Nobody,

however weak compared to Blackburn’s, which was at the moment the crack

football house, ever doubted the result of a match with Kay’s. It was looked on

as a sort of gentle trial trip.

But the efforts of the two captains during the last weeks of the winter term had put a different complexion on matters. Football is not like cricket. It is a game at which anybody of average size and a certain amount of pluck can make himself at least moderately proficient. Kennedy, after consultations with Fenn, had picked out what he considered the best fifteen, and the two set themselves to knock it into shape. In weight there was not much to grumble at. There were several heavy men in the scrum. If only these could be brought to use their weight to the last ounce when shoving, all would be well as far as the forwards were concerned. The outsides were not so satisfactory. With the exception, of course, of Fenn, they lacked speed. They were well-meaning, but they could not run any faster by virtue of that. Kay’s would have to trust to its scrum to pull it through. Peel, the sprinter whom Kennedy had discovered in his search for athletes, had to be put in the pack on account of his weight, which deprived the three-quarter line of what would have been a good man in that position. It was a drawback, too, that Fenn was accustomed to play on the wing. To be of real service, a wing three-quarter must be fed by his centres, and, unfortunately, there was no centre in Kay’s—or Dencroft’s, as it should now be called—who was capable of making openings enough to give Fenn a chance. So he had to play in the centre, where he did not know the game so well.

Kennedy realised at an early date that the one chance of the house was to get together before the house-matches, and play as a coherent team, not as a collection of units. Combination will often make up for lack of speed in a three-quarter line. So twice a week Dencroft’s turned out against scratch teams of varying strength.

It delighted Kennedy to watch their improvement. The first side they played ran through them to the tune of three goals and four tries to a try, and it took all the efforts of the Head of the house to keep a spirit of pessimism from spreading in the ranks. Another frost of this sort, and the sprouting keenness of the house would be nipped in the bud. He conducted himself with much tact. Another captain might have made the fatal error of trying to stir his team up with pungent abuse. He realised what a mistake this would be. It did not need a great deal of discouragement to send the house back to its old slack ways. Another such defeat, following immediately in the footsteps of the first, and they would begin to ask themselves what was the good of mortifying the flesh simply to get a licking from a scratch team by twenty-four points. Kay’s, they would feel, always had got beaten, and they always would, to the end of time. A house that has once got thoroughly slack does not change its views of life in a moment.

Kennedy acted craftily.

“You played jolly well,” he told his despondent team, as they trooped off the field. “We haven’t got together yet, that’s all. And it was a hot side we were playing to-day. They would have licked Blackburn’s.”

A good deal more in the same strain gave the house team the comfortable feeling that they had done uncommonly well to get beaten by only twenty-four points. Kennedy fostered the delusion, and in the meantime arranged with Mr. Dencroft to collect fifteen innocents and lead them forth to be slaughtered by the house on the following Friday. Mr. Dencroft entered into the thing with a relish. When he showed Kennedy the list of his team on the Friday morning, that diplomatist chuckled. He foresaw a good time in the near future. “You must play up like the dickens,” he told the house during the dinner-hour. “Dencroft is bringing a hot lot this afternoon. But I think we shall lick them.”

They did. When the whistle blew for No-Side, the house had just finished scoring its fourteenth try. Six goals and eight tries to nil was the exact total. Dencroft’s returned to headquarters, asking itself in a dazed way if these things could be. They saw that cup on their mantelpiece already. Keenness redoubled. Football became the fashion in Dencroft’s. The play of the team improved weekly. And its spirit improved too. The next scratch team they played beat them by a goal and a try to a goal. Dencroft’s was not depressed. It put the result down to a fluke. Then they beat another side by a try to nothing; and by that time they had got going as an organised team, and their heart was in the thing.

They had improved out of all knowledge when the house-matches began. Blair’s was the lucky house that drew against them in the first round.

“Good business,” said the men of Blair. “Wonder who we’ll play in the second round.”

They left the field marvelling. For some unaccountable reason, Dencroft’s had flatly refused to act in the good old way as a doormat for their opponents. Instead, they had played with a dash and knowledge of the game which for the first quarter of an hour quite unnerved Blair’s. In that quarter of an hour they scored three times, and finished the game with two goals and three tries to their name.

The School looked on it as a huge joke. “Heard the latest?” friends would say on meeting one another the day after the game. “Kay’s—I mean Dencroft’s—have won a match. They simply sat on Blair’s. First time they’ve ever won a house-match, I should think. Blair’s are awfully sick. We shall have to be looking out.”

Whereat the friend would grin broadly. The idea of Dencroft’s making a game of it with his house tickled him.

When Dencroft’s took fifteen points off Mulholland’s, the joke began to lose its humour.

“Why, they must be some good,” said the public, startled at the novelty of the idea. “If they win another match, they’ll be in the final!”

Kay’s in the final! Cricket? Oh, yes, they had got into the final at cricket, of course. But that wasn’t the house. It was Fenn. Footer was different. One man couldn’t do everything there. The only possible explanation was that they had improved to an enormous extent.

Then people began to remember that they had played in scratch games against the house. There seemed to be a tremendous number of fellows who had done this. At one time or another, it seemed, half the School had opposed Dencroft’s in the ranks of a scratch side. It began to dawn on Eckleton that in an unostentatious way Dencroft’s had been putting in about seven times as much practice as any other three houses rolled together. No wonder they combined so well.

When the School House, with three first fifteen men in its team, fell before them, the reputation of Dencroft’s was established. It had reached the final, and only Blackburn’s stood now between it and the cup.

All this while Blackburn’s had been doing what was expected of them by beating each of their opponents with great ease. There was nothing sensational about this as there was in the case of Dencroft’s. The latter were, therefore, favourites when the two teams lined up against one another in the final. The School felt that a house that had had such a meteoric flight as Dencroft’s must—by all that was dramatic—carry the thing through to its obvious conclusion, and pull off the final.

But Fenn and Kennedy were not so hopeful. A certain amount of science, a great deal of keenness, and excellent condition, had carried them through the other rounds in rare style, but, though they would probably give a good account of themselves, nobody who considered the two teams impartially could help seeing that Dencroft’s was a weaker side than Blackburn’s. Nothing but great good luck could bring them out victorious to-day.

And so it proved. Dencroft’s played up for all they were worth from the kick-off to the final solo on the whistle, but they were over-matched. Blackburn’s scrum was too heavy for them, with its three first fifteen men and two seconds. Dencroft’s pack were shoved off the ball time after time, and it was only keen tackling that kept the score down. By half-time Blackburn’s were a couple of tries ahead. Fenn scored soon after the interval with a great run from his own twenty-five, and for a quarter of an hour it looked as if it might be anybody’s game. Kennedy converted the try, so that Blackburn’s only led by a single point. A fluky kick or a mistake on the part of a Blackburnite outside might give Dencroft’s the cup.

But the Blackburn outsides did not make mistakes. They played a strong, sure game, and the forwards fed them well. Ten minutes before No-Side Jimmy Silver ran in, increasing the lead to six points. And though Dencroft’s never went to pieces, and continued to show fight to the very end, Blackburn’s were not to be denied, and Challis scored a final try in the corner. Blackburn’s won the cup by the comfortable, but not excessive, margin of a goal and three tries to a goal.

Dencroft’s had lost the cup; but they had lost it well. Their credit had increased in spite of the defeat.

“I thought we shouldn’t be able to manage Blackburn’s,” said Kennedy, “What we must do now is win that sports’ cup.”

CHAPTER XXIV.

the sports.

HERE were certain houses at Eckleton which had, as it were, specialised in certain

competitions. Thus, Gay’s, who never by any chance survived the first two

rounds of the cricket and football housers, invariably won the shooting shield.

All the other houses sent their brace of men to the range to see what they could

do, but every year it was the same. A pair of weedy obscurities from Gay’s

would take the shield by a comfortable margin. In the same way Mulholland’s had

only won the cricket cup once since they had become a house, but they had

carried off the swimming cup three years in succession, and six years in all

out of the last eight. The sports had always been looked on as the perquisite

of the School House; and this year, with Milligan to win the long distances,

and Maybury the high jump and the weight, there did not seem much doubt at

their success. These two alone would pile up fifteen points. Three points were

given for a win, two for second place, and one for third. It was this that

encouraged Kennedy in the hope that Dencroft’s might have a chance. Nobody in

the house could beat Milligan or Maybury, but the School House second and third

strings were not so invincible. If Dencroft’s, by means of second and third

places in the long races and the other events which were certainties for their

opponents, could hold the School House, Fenn’s sprinting might just give them

the cup. In the meantime they trained hard, but in an unobtrusive fashion which

aroused no fear in School House circles.

HERE were certain houses at Eckleton which had, as it were, specialised in certain

competitions. Thus, Gay’s, who never by any chance survived the first two

rounds of the cricket and football housers, invariably won the shooting shield.

All the other houses sent their brace of men to the range to see what they could

do, but every year it was the same. A pair of weedy obscurities from Gay’s

would take the shield by a comfortable margin. In the same way Mulholland’s had

only won the cricket cup once since they had become a house, but they had

carried off the swimming cup three years in succession, and six years in all

out of the last eight. The sports had always been looked on as the perquisite

of the School House; and this year, with Milligan to win the long distances,

and Maybury the high jump and the weight, there did not seem much doubt at

their success. These two alone would pile up fifteen points. Three points were

given for a win, two for second place, and one for third. It was this that

encouraged Kennedy in the hope that Dencroft’s might have a chance. Nobody in

the house could beat Milligan or Maybury, but the School House second and third

strings were not so invincible. If Dencroft’s, by means of second and third

places in the long races and the other events which were certainties for their

opponents, could hold the School House, Fenn’s sprinting might just give them

the cup. In the meantime they trained hard, but in an unobtrusive fashion which

aroused no fear in School House circles.

The sports were fixed for the last Saturday of term, but not all the races were run on that day. The half-mile came off on the previous Thursday, and the long steeplechase on the Monday after.

The School House won the half-mile, as they were expected to do. Milligan led from the start, increased his lead at the end of the first lap, doubled it half-way through the second, and finally, with a dazzling sprint in the last seventy yards, lowered the Eckleton record by a second and three-fifths, and gave his house three points. Kennedy, who stuck gamely to his man for half the first lap, was beaten on the tape by Crake, of Mulholland’s. When sports day came, therefore, the score was School House three points, Mulholland’s two, Dencroft’s one. The success of Mulholland’s in the half was to the advantage of Dencroft’s. Mulholland’s was not likely to score many more points, and a place to them meant one or two points less to the School House.

The sports opened all in favour of Dencroft’s, but those who knew drew no great consolation from this. School sports always begin with the sprints, and these were Dencroft’s certainties. Fenn won the hundred yards as easily as Milligan had won the half. Peel was second, and a Beddell’s man got third place. So that Dencroft’s had now six points to their rival’s three. Ten minutes later they had increased their lead by winning the first two places at throwing the cricket ball, Fenn’s throw beating Kennedy’s by ten yards, and Kennedy’s being a few feet in front of Jimmy Silver’s, which, by gaining third place, represented the only point Blackburn’s managed to amass during the afternoon.

It now began to dawn upon the School House that their supremacy was seriously threatened. Dencroft’s, by its success in the football competition, had to a great extent lived down the reputation the house had acquired when it had been Kay’s, but even now the notion of its winning a cup seemed somehow vaguely improper. But the fact had to be faced that it now led by eleven points to the School House’s three.

“It’s all right,” said the School House, “our spot events haven’t come off yet. Dencroft’s can’t get much more now.”

And, to prove that they were right, the gap between the two scores began gradually to be filled up. Dencroft’s struggled hard, but the School House total crept up and up. Maybury brought it to six by winning the high jump. This was only what had been expected of him. The discomforting part of the business was that the other two places were filled by Morrell, of Mulholland’s, and Smith, of Daly’s. And when, immediately afterwards, Maybury won the weight, with another School House man second, leaving Dencroft’s with third place only, things began to look black for the latter. They were now only one point ahead, and there was the mile to come: and Milligan could give any Dencroftian a hundred yards at that distance.

But to balance the mile there was the quarter, and in the mile Kennedy contrived to beat Crake by much the same number of feet as Crake had beaten him by in the half. The scores of the two houses were now level, and a goodly number of the School House certainties were past.

Dencroft’s forged ahead again by virtue of the quarter-mile. Fenn won it; Peel was second; and a dark horse from Denny’s got in third. With the greater part of the sports over, and a lead of five points to their name, Dencroft’s could feel more comfortable. The hurdle-race was productive of some discomfort. Fenn should have won it, as being blessed with twice the pace of any of his opponents. But Maybury, the jumper, made up for lack of pace by the scientific way in which he took his hurdles, and won off him by a couple of feet. Smith, Dencroft’s second string, finished third, thus leaving the totals unaltered by the race.

By this time the public had become alive to the fact that Dencroft’s were making a great fight for the cup. They had noticed that Dencroft’s colours always seemed to be coming in near the head of the procession, but the School House had made the cup so much their own, that it took some time for the school to realise that another house—especially the late Kay’s—was running them hard for first place. Then, just before the hurdle-race, fellows with “correct cards” hastily totted up the points each house had won up-to-date. To the general amazement it was found that, while the School House had fourteen, Dencroft’s had reached nineteen, and, barring the long run to be decided on the Monday, there was nothing now that the School House must win without dispute.

A house that will persist in winning a cup year after year has to pay for it when challenged by a rival. Dencroft’s instantly became warm favourites. Whenever Dencroft’s brown and gold appeared at the scratch, the school shouted for it wildly till the event was over. By the end of the day the totals were more nearly even, but Dencroft’s were still ahead. They had lost on the long jump, but not unexpectedly. The totals at the finish were, School House twenty-three, Dencroft’s twenty-five. Everything now depended on the long run.

“We might do it,” said Kennedy to Fenn, as they changed. “Milligan’s a cert for three points, of course, but if we can only get two we win the cup.”

“There’s one thing about the long run,” said Fenn; “you never quite know what’s going to happen. Milligan might break down over one of the hedges or the brook. There’s no telling.”

Kennedy felt that such a remote possibility was something of a broken reed to lean on. He had no expectation of beating the School House long distance runner, but he hoped for second place; and second place would mean the cup, for there was nobody to beat either himself or Crake.

The distance of the long run was as nearly as possible five miles. The course was across country to the village of Ledby in a sort of semicircle of three and a half miles, and then back to the school gates by road. Every Eckletonian who ran at all knew the route by heart. It was the recognised training run if you wanted to train particularly hard. If you did not, you took a shorter spin. At the milestone nearest the school—it was about half a mile from the gates—a good number of fellows used to wait to see the first of the runners and pace their men home. But, as a rule, there were few really hot finishes in the long run. The man who got to Ledby first generally kept the advantage, and came in a long way ahead of the field.

On this occasion the close fight Kennedy and Crake had had in the mile and the half, added to the fact that Kennedy had only to get second place to give Dencroft’s the cup, lent a greater interest to the race than usual. The crowd at the milestone was double the size of the one in the previous year, when Milligan had won for the first time. And when, amidst howls of delight from the School House, the same runner ran past the stone with his long, effortless stride, before any of the others were in sight, the crowd settled down breathlessly to watch for the second man.

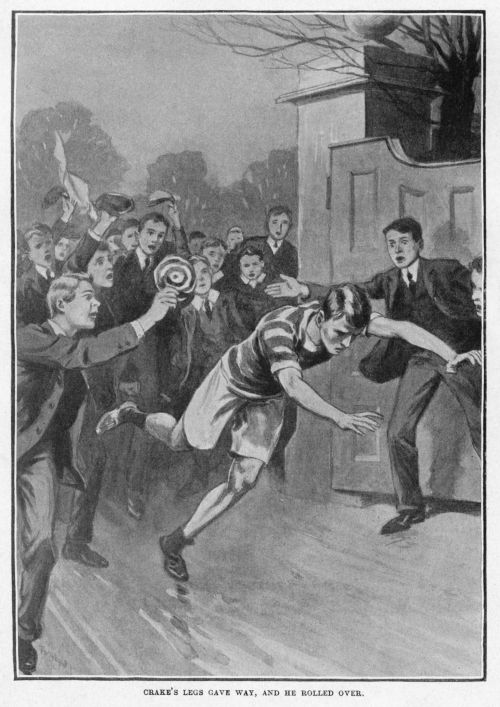

Then a yell, to which the other had been nothing, burst from the School House as a white figure turned the corner. It was Crake. Waddling rather than running, and breathing in gasps; but still Crake. He toiled past the crowd at the milestone.

“By Jove, he looks bad,” said someone.

And, indeed, he looked very bad. But he was ahead of Kennedy. That was the great thing.

He had passed the stone by thirty yards, when the cheering broke out again. Kennedy this time, in great straits, but in better shape than Crake. Dencroft’s in a body trotted along at the side of the road, shouting as they went. Crake, hearing the shouts, looked round, almost fell, and then pulled himself together and staggered on again. There were only a hundred yards to go now, and the school gates were in sight at the end of a long lane of spectators. They looked to Kennedy like two thick, black hedges. He could not sprint, though a hundred voices were shouting to him to do so. It was as much as he could do to keep moving. Only his will enabled him to run now. He meant to get to the gates, if he had to crawl.

The hundred yards dwindled to fifty, and he had diminished Crake’s lead by a third. Twenty yards from the gates, and he was only half-a-dozen yards behind.

Crake looked round again, and this time did what he had nearly done before. His legs gave way; he rolled over; and there he remained, with the School House watching him in silent dismay, while Kennedy went on and pitched in a heap on the other side of the gates.

* * * * *

“Feeling bad?” said Jimmy Silver, looking in that evening to make inquiries.

“I’m feeling good,” said Kennedy.

“That the cup?” asked Jimmy.

Kennedy took the huge cup from the table.

“That’s it. Milligan has just brought it round. Well, they can’t say they haven’t had their fair share of it. Look here. School House. School House. School House. School House. Daly’s. School House. Denny’s. School House. School House. Ad infinitum.”

They regarded the trophy in silence.

“First pot the house has won,” said Kennedy at length. “The very first.”

“It won’t be the last,” returned Jimmy Silver, with decision.

the end.

Editor’s notes:

Eugene Aram’s victim: See Thomas Hood’s poem “The Dream of Eugene Aram.”

unequal to the intellectual pressure of the conversation: from W. S. Gilbert’s libretto of The Gondoliers.

things in heaven and earth: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Hamlet, I, v.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums