The Captain, December 1909

* Former tales about “Psmith” are “The Lost Lambs” and “The New Fold,” in Vols. XIX and XX of The Captain.

CHAPTER XI.

the man at the astor.

HE duties of Master Pugsy Maloney at the offices of Cosy

Moments were not heavy; and he was accustomed to occupy his large store of

leisure by reading narratives dealing with life in the prairies, which he

acquired at a neighbouring shop at cut rates in consideration of their being

shop-soiled. It was while he was engrossed in one of these, on the morning

following the visit of Mr. Parker, that the seedy-looking man made his

appearance. He walked in from the street, and stood before Master Maloney.

HE duties of Master Pugsy Maloney at the offices of Cosy

Moments were not heavy; and he was accustomed to occupy his large store of

leisure by reading narratives dealing with life in the prairies, which he

acquired at a neighbouring shop at cut rates in consideration of their being

shop-soiled. It was while he was engrossed in one of these, on the morning

following the visit of Mr. Parker, that the seedy-looking man made his

appearance. He walked in from the street, and stood before Master Maloney.

“Hey, kid,” he said.

Pugsy looked up with some hauteur. He resented being addressed as “kid” by perfect strangers.

“Editor in, Tommy?” inquired the man.

Pugsy by this time had taken a thorough dislike to him. To be called “kid” was bad. The subtle insult of “Tommy” was still worse.

“Nope,” he said curtly, fixing his eyes again on his book. A movement on the

part of the visitor attracted his attention. The seedy man was making for the

door of the inner room. Pugsy instantly ceased to be the student and became the

man of action. He sprang from his seat and wriggled in between the man and the

door.

“Nope,” he said curtly, fixing his eyes again on his book. A movement on the

part of the visitor attracted his attention. The seedy man was making for the

door of the inner room. Pugsy instantly ceased to be the student and became the

man of action. He sprang from his seat and wriggled in between the man and the

door.

“Youse can’t butt in dere,” he said authoritatively. “Chase yerself.”

The man eyed him with displeasure.

“Fresh kid!” he observed disapprovingly.

“Fade away,” urged Master Maloney.

The visitor’s reply was to extend a hand and grasp Pugsy’s left ear between a long finger and thumb. Since time began, small boys in every country have had but one answer for this action. Pugsy made it. He emitted a piercing squeal in which pain, fear, and resentment strove for supremacy.

The noise penetrated into the editorial sanctum, losing only a small part of its strength on the way. Psmith, who was at work on a review of a book of poetry, looked up with patient sadness.

“If Comrade Maloney,” he said, “is going to take to singing as well as whistling, I fear this journal must put up its shutters. Concentrated thought will be out of the question.”

A second squeal rent the air. Billy Windsor jumped up.

“Somebody must be hurting the kid,” he exclaimed.

He hurried to the door and flung it open. Psmith followed at a more leisurely pace. The seedy man, caught in the act, released Master Maloney, who stood rubbing his ear with resentment written on every feature.

On such occasions as this Billy was a man of few words. He made a dive for the seedy man; but the latter, who during the preceding moment had been eyeing the two editors as if he were committing their appearance to memory, sprang back, and was off down the stairs with the agility of a Marathon runner.

“He blows in,” said Master Maloney, aggrieved, “and asks is de editor dere. I tells him no, ’cos youse said youse wasn’t, and he nips me by the ear when I gets busy to stop him gettin’ t’roo.”

“Comrade Maloney,” said Psmith, “You are a martyr. What would Horatius have done if somebody had nipped him by the ear when he was holding the bridge? The story does not consider the possibility. Yet it might have made all the difference. Did the gentleman state his business?”

“Nope. Just tried to butt t’roo.”

“Another of these strong silent men. The world is full of us. These are the perils of the journalistic life. You will be safer and happier when you are rounding up cows on your mustang.”

“I wonder what he wanted,” said Billy, when they were back again in the inner room.

“Who can say, Comrade Windsor? Possibly our autographs. Possibly five minutes’ chat on general subjects.”

“I don’t like the look of him,” said Billy.

“Whereas what Comrade Maloney objected to was the feel of him. In what respect did his look jar upon you? His clothes were poorly cut, but such things, I know, leave you unmoved.”

“It seems to me,” said Billy thoughtfully, “as if he came just to get a sight of us.”

“And he got it. Ah, Providence is good to the poor.”

“Whoever’s behind those tenements isn’t going to stick at any odd trifle. We must watch out. That man was probably sent to mark us down for one of the gangs. Now they’ll know what we look like, and they can get after us.”

“These are the drawbacks to being public men, Comrade Windsor. We must bear them manfully, without wincing.”

Billy turned again to his work.

“I’m not going to wince,” he said, “so’s you could notice it with a microscope. What I’m going to do is to buy a good big stick. And I’d advise you to do the same.”

It was by Psmith’s suggestion that the editorial staff of Cosy Moments dined that night in the roof-garden at the top of the Astor Hotel.

“The tired brain,” he said, “needs to recuperate. To feed on such a night as this in some low-down hostelry on the level of the street, with German waiters breathing heavily down the back of one’s neck and two fiddles and a piano whacking out ‘Beautiful Eyes’ about three feet from one’s tympanum, would be false economy. Here, fanned by cool breezes and surrounded by fair women and brave men, one may do a bit of tissue-restoring. Moreover, there is little danger up here of being slugged by our moth-eaten acquaintance of this morning. A man with trousers like his would not be allowed in. We shall probably find him waiting for us at the main entrance with a sand-bag, when we leave, but, till then——”

He turned with gentle grace to his soup.

It was a warm night, and the roof-garden was full. From where they sat they could see the million twinkling lights of the city. Towards the end of the meal, Psmith’s gaze concentrated itself on the advertisement of a certain brand of ginger-ale in Times Square. It is a mass of electric light arranged in the shape of a great bottle, and at regular intervals there proceed from the bottle’s mouth flashes of flame representing ginger-ale. The thing began to exercise a hypnotic effect on Psmith. He came to himself with a start, to find Billy Windsor in conversation with a waiter.

“Yes, my name’s Windsor,” Billy was saying.

The waiter bowed and retired to one of the tables where a young man in evening clothes was seated. Psmith recollected having seen this solitary diner looking in their direction once or twice during dinner, but the fact had not impressed him.

“What is happening, Comrade Windsor?” he inquired. “I was musing with a certain tenseness at the moment, and the rush of events has left me behind.”

“Man at that table wanted to know if my name was Windsor,” said Billy.

“Ah?” said Psmith, interested; “and was it?”

“Here he comes. I wonder what he wants. I don’t know the man from Adam.”

The stranger was threading his way between the tables.

“Can I have a word with you, Mr. Windsor?” he said.

Billy looked at him curiously. Recent events had made him wary of strangers.

“Won’t you sit down?” he said.

A waiter was bringing a chair. The young man seated himself.

“By the way,” added Billy; “my friend, Mr. Smith.”

“Pleased to meet you,” said the other.

“I don’t know your name,” Billy hesitated.

“Never mind about my name,” said the stranger. “It won’t be needed. Is Mr. Smith on your paper? Excuse my asking.”

Psmith bowed.

“That’s all right, then. I can go ahead.”

He bent forward.

“Neither of you gentlemen are hard of hearing, eh?”

“In the old prairie days,” said Psmith, “Comrade Windsor was known to the Indians as Boola-Ba-Na-Gosh, which, as you doubtless know, signifies Big-Chief-Who-Can-Hear-A-Fly-Clear-Its-Throat. I too can hear as well as the next man. Why?”

“That’s all right, then. I don’t want to have to shout it. There’s some things it’s better not to yell.”

He turned to Billy, who had been looking at him all the while with a combination of interest and suspicion. The man might or might not be friendly. In the meantime, there was no harm in being on one’s guard. Billy’s experience as a cub-reporter had given him the knowledge that is only given in its entirety to police and newspaper men: that there are two New Yorks. One is a modern, well-policed city, through which one may walk from end to end without encountering adventure. The other is a city as full of sinister intrigue, of whisperings and conspiracies, of battle, murder, and sudden death in dark by-ways, as any town of mediæval Italy. Given certain conditions, anything may happen to any one in New York. And Billy realised that these conditions now prevailed in his own case. He had come into conflict with New York’s underworld. Circumstances had placed him below the surface, where only his wits could help him.

“It’s about that tenement business,” said the stranger.

Billy bristled. “Well, what about it?” he demanded truculently.

The stranger raised a long and curiously delicately shaped hand. “Don’t bite at me,” he said. “This isn’t my funeral. I’ve no kick coming. I’m a friend.”

“Yet you don’t tell us your name.”

“Never mind my name. If you were in my line of business, you wouldn’t be so durned stuck on this name thing. Call me Smith, if you like.”

“You could select no nobler pseudonym,” said Psmith cordially.

“Eh? Oh, I see. Well, make it Brown, then. Anything you please. It don’t signify. See here, let’s get back. About this tenement thing. You understand certain parties have got it in against you?”

“A charming conversationalist, one Comrade Parker, hinted at something of the sort,” said Psmith, “in a recent interview. Cosy Moments, however, cannot be muzzled.”

“Well?” said Billy.

“You’re up against a big proposition.”

“We can look after ourselves.”

“Gum! you’ll need to. The man behind is a big bug.”

Billy leaned forward eagerly.

“Who is he?”

The other shrugged his shoulders.

“I don’t know. You wouldn’t expect a man like that to give himself away.”

“Then how do you know he’s a big bug?”

“Precisely,” said Psmith. “On what system have you estimated the size of the gentleman’s bughood?”

The stranger lit a cigar.

“By the number of dollars he was ready to put up to have you done in.”

Billy’s eyes snapped.

“Oh?” he said. “And which gang has he given the job to?”

“I wish I could tell you. He—his agent, that is—came to Bat Jarvis.”

“The cat-expert?” said Psmith. “A man of singularly winsome personality.”

“Bat turned the job down.”

“Why was that?” inquired Billy.

“He said he needed the money as much as the next man, but when he found out who he was supposed to lay for, he gave his job the frozen face. Said you were a friend of his and none of his fellows were going to put a finger on you. I don’t know what you’ve been doing to Bat, but he’s certainly Willie the Long-Lost Brother with you.”

“A powerful argument in favour of kindness to animals!” said Psmith. “Comrade Windsor came into possession of one of Comrade Jarvis’s celebrated stud of cats. What did he do? Instead of having the animal made into a nourishing soup, he restored it to its bereaved owner. Observe the sequel. He is now as a prize tortoiseshell to Comrade Jarvis.”

“So Bat wouldn’t stand for it?” said Billy.

“Not on his life. Turned it down without a blink. And he sent me along to find you and tell you so.”

“We are much obliged to Comrade Jarvis,” said Psmith.

“He told me to tell you to watch out, because another gang is dead sure to take on the job. But he said you were to know he wasn’t mixed up in it. He also said that any time you were in bad, he’d do his best for you. You’ve certainly made the biggest kind of hit with Bat. I haven’t seen him so worked up over a thing in years. Well, that’s all, I reckon. Guess I’ll be pushing along. I’ve a date to keep. Glad to have met you. Glad to have met you, Mr. Smith. Pardon me, you have an insect on your coat.”

He flicked at Psmith’s coat with a quick movement. Psmith thanked him gravely.

“Good-night,” concluded the stranger, moving off. For a few moments after he had gone, Psmith and Billy sat smoking in silence. They had plenty to think about.

“How’s the time going?” asked Billy at length. Psmith felt for his watch, and looked at Billy with some sadness.

“I am sorry to say, Comrade Windsor——”

“Hullo,” said Billy, “here’s that man coming back again.”

The stranger came up to their table, wearing a light overcoat over his dress clothes. From the pocket of this he produced a gold watch.

“Force of habit,” he said apologetically, handing it to Psmith. “You’ll pardon me. Good-night, gentlemen, again.”

HE Astor Hotel faces on to

Times Square. A few paces to the right of the main entrance the Times Building

towers to the sky; and at the foot of this the stream of traffic breaks, forming

two channels. To the right of the building is Seventh Avenue, quiet, dark, and

dull. To the left is Broadway, the Great White Way, the longest, straightest,

brightest, wickedest street in the world.

HE Astor Hotel faces on to

Times Square. A few paces to the right of the main entrance the Times Building

towers to the sky; and at the foot of this the stream of traffic breaks, forming

two channels. To the right of the building is Seventh Avenue, quiet, dark, and

dull. To the left is Broadway, the Great White Way, the longest, straightest,

brightest, wickedest street in the world.

Psmith and Billy, having left the Astor, started to walk down Broadway to Billy’s lodgings in Fourteenth Street. The usual crowd was drifting slowly up and down in the glare of the white lights.

They had reached Herald Square, when a voice behind them exclaimed, “Why, it’s Mr. Windsor!”

They wheeled round. A flashily-dressed man was standing with outstetched hand.

“I saw you come out of the Astor,” he said cheerily. “I said to myself, ‘I know that man.’ Darned if I could put a name to you, though. So I just followed you along, and right here it came to me.”

“It did, did it?” said Billy politely.

“It did, sir. I’ve never set eyes on you before, but I’ve seen so many photographs of you that I reckon we’re old friends. I know your father very well, Mr. Windsor. He showed me the photographs. You may have heard him speak of me—Jack Lake? How is the old man? Seen him lately?”

“Not for some time. He was well when he last wrote.”

“Good for him. He would be. Tough as a plank, old Joe Windsor. We always called him Joe.”

“You’d have known him down in Missouri, of course?” said Billy.

“That’s right. In Missouri. We were side-partners for years. Now, see here, Mr. Windsor, it’s early yet. Won’t you and your friend come along with me and have a smoke and a chat? I live right here in Thirty-Third Street. I’d be right glad for you to come.”

“I don’t doubt it,” said Billy, “but I’m afraid you’ll have to excuse us.”

“In a hurry, are you?”

“Not in the least.”

“Then come right along.”

“No, thanks.”

“Say, why not? It’s only a step.”

“Because we don’t want to. Good-night.”

He turned, and started to walk away. The other stood for a moment, staring; then crossed the road.

Psmith broke the silence.

“Correct me if I am wrong, Comrade Windsor,” he said tentatively, “but were you not a trifle—shall we say abrupt?—with the old family friend?”

Billy Windsor laughed.

“If my father’s name was Joseph,” he said, “instead of being William, the same as mine, and if he’d ever been in Missouri in his life, which he hasn’t, and if I’d been photographed since I was a kid, which I haven’t been, I might have gone along. As it was, I thought it better not to.”

“These are deep waters, Comrade Windsor. Do you mean to intimate——?”

“If they can’t do any better than that, we sha’n’t have much to worry us. What do they take us for, I wonder? Farmers? Playing off a comic-supplement bluff like that on us!”

There was honest indignation in Billy’s voice.

“You think, then, that if we had accepted Comrade Lake’s invitation, and gone along for a smoke and a chat, the chat would not have been of the pleasantest nature?”

“We should have been put out of business.”

“I have heard so much,” said Psmith, thoughtfully, “of the lavish hospitality of the American.”

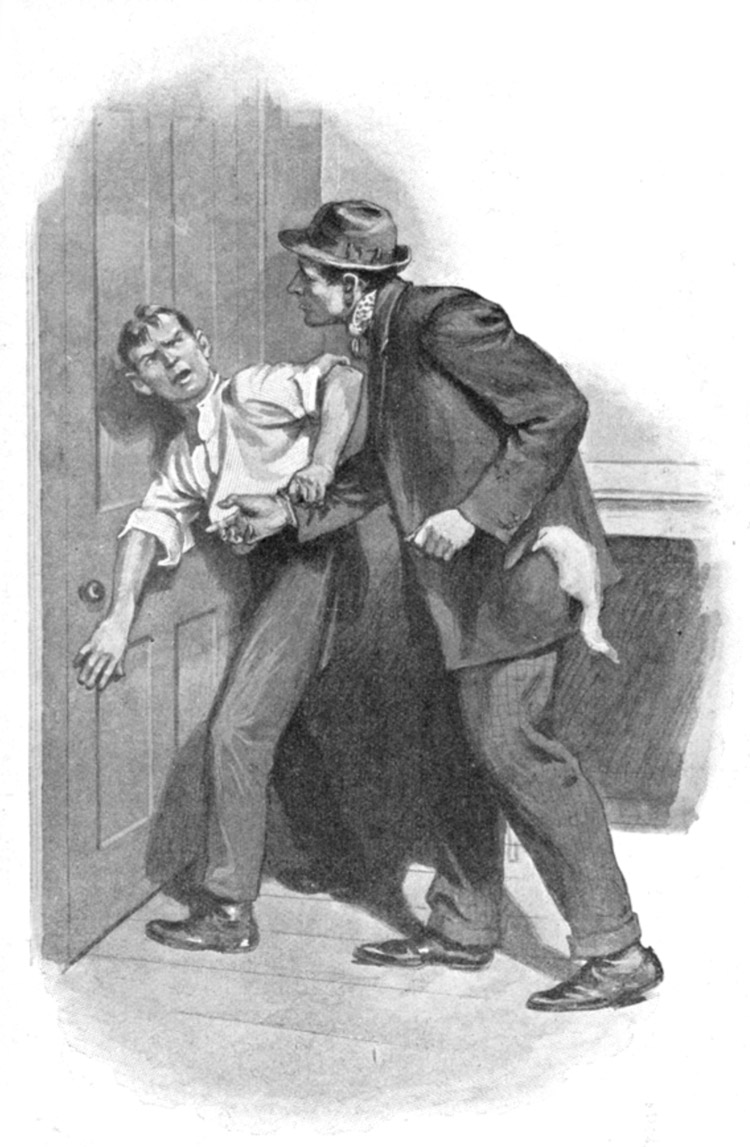

“Taxi, sir?”

A red taximeter cab was crawling down the road at their side. Billy shook his head.

“Not that a taxi would be an unsound scheme,” said Psmith.

“Not that particular one, if you don’t mind.”

“Something about it that offends your aesthetic taste?” queried Psmith sympathetically.

“Something about it makes my aesthetic taste kick like a mule,” said Billy.

“Ah, we highly-strung literary men do have these curious prejudices. We cannot help it. We are the slaves of our temperaments. Let us walk, then. After all, the night is fine, and we are young and strong.”

They had reached Twenty-third Street when Billy stopped. “I don’t know about walking,” he said. “Suppose we take the Elevated?”

“Anything you wish, Comrade Windsor. I am in your hands.”

They cut across into Sixth Avenue, and walked up the stairs to the station of the Elevated Railway. A train was just coming in.

“Has it escaped your notice, Comrade Windsor,” said Psmith after a pause, “that, so far from speeding to your lodgings, we are going in precisely the opposite direction? We are in an up-town train.”

“I noticed it,” said Billy briefly.

“Are we going anywhere in particular?”

“This train goes as far as Hundred and Tenth Street. We’ll go up to there.”

“And then?”

“And then we’ll come back.”

“And after that, I suppose, we’ll make a trip to Philadelphia, or Chicago, or somewhere? Well, well, I am in your hands, Comrade Windsor. The night is yet young. Take me where you will. It is only five cents a go, and we have money in our purses. We are two young men out for reckless dissipation. By all means let us have it.”

At a Hundred and Tenth Street they left the train, went down the stairs, and crossed the street. Half-way across Billy stopped.

“What now, Comrade Windsor?” inquired Psmith patiently. “Have you thought of some new form of entertainment?”

Billy was making for a spot some few yards down the road. Looking in that direction, Psmith saw his objective. In the shadow of the Elevated there was standing a taximeter cab.

“Taxi, sir?” said the driver, as they approached.

“We are giving you a great deal of trouble,” said Billy. “You must be losing money over this job. All this while you might be getting fares down-town.”

“These meetings, however,” urged Psmith, “are very pleasant.”

“I can save you worrying,” said Billy. “My address is 84 East Fourteenth Street. We are going back there now.”

“Search me,” said the driver, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“I thought perhaps you did,” replied Billy. “Good-night.”

“These things are very disturbing,” said Psmith, when they were in the train. “Dignity is impossible when one is compelled to be the Hunted Fawn. When did you begin to suspect that yonder merchant was doing the sleuth-hound act?”

“When I saw him in Broadway having a heart-to-heart talk with our friend from Missouri.”

“He must be something of an expert at the game to have kept on our track.”

“Not on your life. It’s as easy as falling off a log. There are only certain places where you can get off an Elevated train. All he’d got to do was to get there before the train, and wait. I didn’t expect to dodge him by taking the Elevated. I just wanted to make certain of his game.”

The train pulled up at the Fourteenth Street station. In the roadway at the foot of the opposite staircase was a red taximeter cab.

CHAPTER XIII.

reviewing the situation.

RRIVING at the bed-sitting-room, Billy proceeded to occupy

the rocking-chair, and, as was his wont, began to rock himself rhythmically to

and fro. Psmith seated himself gracefully on the couch-bed. There was a

silence.

RRIVING at the bed-sitting-room, Billy proceeded to occupy

the rocking-chair, and, as was his wont, began to rock himself rhythmically to

and fro. Psmith seated himself gracefully on the couch-bed. There was a

silence.

The events of the evening had been a revelation to Psmith. He had not realised before the extent of the ramifications of New York’s underworld. That members of the gangs should crop up in the Astor roof-garden and in gorgeous raiment in the middle of Broadway was a surprise. When Billy Windsor had mentioned the gangs, he had formed a mental picture of low-browed hooligans, keeping carefully to their own quarter of the town. This picture had been correct, as far as it went, but it had not gone far enough. The bulk of the gangs of New York are of the hooligan class, and are rarely met with outside their natural boundaries. But each gang has its more prosperous members; gentlemen, who, like the man of the Astor roof-garden, support life by more delicate and genteel methods than the rest. The main body rely for their incomes, except at election-time, on such primitive feats as robbing intoxicated pedestrians. The aristocracy of the gangs soar higher.

It was a considerable time before Billy spoke.

“Say,” he said, “this thing wants talking over.”

“By all means, Comrade Windsor.”

“It’s this way. There’s no doubt now that we’re up against a mighty big proposition.”

“Something of the sort would seem to be the case.”

“It’s like this. I’m going to see this through. It isn’t only that I want to do a bit of good to the poor cusses in those tenements, though I’d do it for that alone. But, as far as I’m concerned, there’s something to it besides that. If we win out, I’m going to get a job out of one of the big dailies. It’ll give me just the chance I need. See what I mean? Well, it’s different with you. I don’t see that it’s up to you to run the risk of getting yourself put out of business with a black-jack, and maybe shot. Once you get mixed up with the gangs there’s no saying what’s going to be doing. Well, I don’t see why you shouldn’t quit. All this has got nothing to do with you. You’re over here on a vacation. You haven’t got to make a living this side. You want to go about and have a good time, instead of getting mixed up with——”

He broke off.

“Well, that’s what I wanted to say, anyway,” he concluded.

Psmith looked at him reproachfully.

“Are you trying to sack me, Comrade Windsor?”

“How’s that?”

“In various treatises on ‘How to Succeed in Literature,’ ” said Psmith sadly, “which I have read from time to time, I have always found it stated that what the novice chiefly needed was an editor who believed in him. In you, Comrade Windsor, I fancied that I had found such an editor.”

“What’s all this about?” demanded Billy. “I’m making no kick about your work.”

“I gathered from your remarks that you were anxious to receive my resignation.”

“Well, I told you why. I didn’t want you be black-jacked.”

“Was that the only reason?”

“Sure.”

“Then all is well,” said Psmith, relieved. “For the moment I fancied that my literary talents had been weighed in the balance and adjudged below par. If that is all—why, these are the mere everyday risks of the young journalist’s life. Without them we should be dull and dissatisfied. Our work would lose its fire. Men such as ourselves, Comrade Windsor, need a certain stimulus, a certain fillip, if they are to keep up their high standards. The knowledge that a low-browed gentleman is waiting round the corner with a sand-bag poised in air will just supply that stimulus. Also that fillip. It will give our output precisely the edge it requires.”

“Then you’ll stay in this thing? You’ll stick to the work?”

“Like a conscientious leech, Comrade Windsor.”

“Bully for you,” said Billy.

It was not Psmith’s habit, when he felt deeply on any subject, to exhibit his feelings; and this matter of the tenements had hit him harder than any one who did not know him intimately would have imagined. Mike would have understood him, but Billy Windsor was too recent an acquaintance. Psmith was one of those people who are content to accept most of the happenings of life in an airy spirit of tolerance. Life had been more or less of a game with him up till now. In his previous encounters with those with whom fate had brought him in contact there had been little at stake. The prize of victory had been merely a comfortable feeling of having had the best of a battle of wits; the penalty of defeat nothing worse than the discomfort of having failed to score. But this tenement business was different. Here he had touched the realities. There was something worth fighting for. His lot had been cast in pleasant places, and the sight of actual raw misery had come home to him with an added force from that circumstance. He was fully aware of the risks that he must run. The words of the man at the Astor, and still more the episodes of the family friend from Missouri and the taximeter cab, had shown him that this thing was on a different plane from anything that had happened to him before. It was a fight without the gloves, and to a finish at that. But he meant to see it through. Somehow or other those tenement houses had got to be cleaned up. If it meant trouble, as it undoubtedly did, that trouble would have to be faced.

“Now that Comrade Jarvis,” he said, “showing a spirit of forbearance which, I am bound to say, does him credit, has declined the congenial task of fracturing our occiputs, who should you say, Comrade Windsor, would be the chosen substitute?”

Billy shook his head. “Now that Bat has turned up the job, it might be any one of three gangs. There are four main gangs, you know. Bat’s is the biggest. But the smallest of them’s large enough to put us away, if we give them the chance.”

“I don’t quite grasp the nice points of this matter. Do you mean that we have an entire gang on our trail in one solid mass, or will it be merely a section?”

“Well, a section, I guess, if it comes to that. Parker, or whoever fixed this thing up, would go to the main boss of the gang. If it was the Three Points, he’d go to Spider Reilly. If it was the Table Hill lot, he’d look up Dude Dawson. And so on.”

“And what then?”

“And then the boss would talk it over with his own special partners. Every gang-leader has about a dozen of them. A sort of Inner Circle. They’d fix it up among themselves. The rest of the gang wouldn’t know anything about it. The fewer in the game, you see, the fewer to split up the dollars.”

“I see. Then things are not so black. All we have to do is to look out for about a dozen hooligans with a natural dignity in their bearing, the result of intimacy with the main boss. Carefully eluding these aristocrats, we shall win through. I fancy, Comrade Windsor, that all may yet be well. What steps do you propose to take by way of self-defence?”

“Keep out in the middle of the street, and not go off the Broadway after dark. You’re pretty safe on Broadway. There’s too much light for them there.”

“Now that our sleuth-hound friend in the taximeter has ascertained your address, shall you change it?”

“It wouldn’t do any good. They’d soon find where I’d gone to. How about yours?”

“I fancy I shall be tolerably all right. A particularly massive policeman is on duty at my very doors. So much for our private lives. But what of the day-time? Suppose these sandbag-specialists drop in at the office during business hours. Will Comrade Maloney’s frank and manly statement that we are not in be sufficient to keep them out? I doubt it. All unused to the nice conventions of polite society, these rugged persons will charge through. In such circumstances good work will be hard to achieve. Your literary man must have complete quiet if he is to give the public of his best. But stay. An idea!”

“Well?”

“Comrade Brady. The Peerless Kid. The man Cosy Moments is running for the light-weight championship. We are his pugilistic sponsors. You may say that it is entirely owing to our efforts that he has obtained this match with—who exactly is the gentleman Comrade Brady fights at the Highfield Club on Friday night?”

“Cyclone Al. Wolmann, isn’t it?”

“You are right. As I was saying, but for us the privilege of smiting Comrade Cyclone Al. Wolmann under the fifth rib on Friday night would almost certainly have been denied to him.”

It almost seemed as if he were right. From the moment the paper had taken up his cause, Kid Brady’s star had undoubtedly been in the ascendant. People began to talk about him as a likely man. Edgren, in the Evening World, had a paragraph about his chances for the light-weight title. Tad, in the Journal, drew a picture of him. Finally, the management of the Highfield Club had signed him for a ten-round bout with Mr. Wolmann. There were, therefore, reasons why Cosy Moments should feel a claim on the Kid’s services.

“He should,” continued Psmith, “if equipped in any degree with finer feelings, be bubbling over with gratitude towards us. ‘But for Cosy Moments,’ he should be saying to himself, ‘where should I be? Among the also-rans.’ I imagine that he will do any little thing we care to ask of him. I suggest that we approach Comrade Brady, explain the facts of the case, and offer him at a comfortable salary the post of fighting-editor of Cosy Moments. His duties will be to sit in the room opening out of ours, girded as to the loins and full of martial spirit, and apply some of those half-scissor hooks of his to the persons of any who overcome the opposition of Comrade Maloney. We, meanwhile, will enjoy that leisure and freedom from interruption which is so essential to the artist.”

“It’s not a bad idea,” said Billy.

“It is about the soundest idea,” said Psmith, “that has ever been struck. One of your newspaper friends shall supply us with tickets, and Friday night shall see us at the Highfield.”

AR up at the other end of the island, on the banks of the

Harlem River, there stands the old warehouse which modern progress has converted

into the Highfield Athletic and Gymnastic Club. The imagination, stimulated by

the title, conjures up a sort of National Sporting Club, with pictures on the

walls, padding on the chairs, and a sea of white shirt-fronts from roof to

floor. But the Highfield differs in some respects from this fancy picture.

Indeed, it would be hard to find a respect in which it does not differ. But

these names are so misleading. The title under which the Highfield used to be

known till a few years back was “Swifty Bob’s.” It was a good, honest title. You

knew what to expect; and if you attended séances at Swifty Bob’s you left

your gold watch and your little savings at home. But a wave of anti-pugilistic

feeling swept over the New York authorities. Promoters of boxing contests found

themselves, to their acute disgust, raided by the police. The industry began to

languish. People avoided places where at any moment the festivities might be

marred by an inrush of large men in blue uniforms, armed with locust-sticks.

AR up at the other end of the island, on the banks of the

Harlem River, there stands the old warehouse which modern progress has converted

into the Highfield Athletic and Gymnastic Club. The imagination, stimulated by

the title, conjures up a sort of National Sporting Club, with pictures on the

walls, padding on the chairs, and a sea of white shirt-fronts from roof to

floor. But the Highfield differs in some respects from this fancy picture.

Indeed, it would be hard to find a respect in which it does not differ. But

these names are so misleading. The title under which the Highfield used to be

known till a few years back was “Swifty Bob’s.” It was a good, honest title. You

knew what to expect; and if you attended séances at Swifty Bob’s you left

your gold watch and your little savings at home. But a wave of anti-pugilistic

feeling swept over the New York authorities. Promoters of boxing contests found

themselves, to their acute disgust, raided by the police. The industry began to

languish. People avoided places where at any moment the festivities might be

marred by an inrush of large men in blue uniforms, armed with locust-sticks.

And then some big-brained person suggested the club idea, which stands alone as an example of American dry humour. There are now no boxing contests in New York. Swifty Bob and his fellows would be shocked at the idea of such a thing. All that happens now is exhibition sparring bouts between members of the club. It is true that next day the papers very tactlessly report the friendly exhibition spar as if it had been quite a serious affair, but that is not the fault of Swifty Bob.

Kid Brady, the chosen of Cosy Moments, was billed for a “ten-round exhibition contest,” to be the main event of the evening’s entertainment. No decisions are permitted at these clubs. Unless a regrettable accident occurs, and one of the sparrers is knocked out, the verdict is left to the newspapers next day. It is not uncommon to find a man win easily in the World, draw in the American, and be badly beaten in the Evening Mail. The system leads to a certain amount of confusion, but it has the merit of offering consolation to a much-smitten warrior.

The best method of getting to the Highfield is by the Subway. To see the Subway in its most characteristic mood one must travel on it during the rush-hour, when its patrons are packed into the carriages in one solid jam by muscular guards and policemen, shoving in a manner reminiscent of a Rugby football scrum. When Psmith and Billy entered it on the Friday evening, it was comparatively empty. All the seats were occupied, but only a few of the straps and hardly any of the space reserved by law for the conductor alone.

Conversation on the Subway is impossible. The ingenious gentlemen who constructed it started with the object of making it noisy. Not ordinarily noisy, like a ton of coal falling on to a sheet of tin, but really noisy. So they fashioned the pillars of thin steel, and the sleepers of thin wood, and loosened all the nuts, and now a Subway train in motion suggests a prolonged dynamite explosion blended with the voice of some great cataract.

Psmith, forced into temporary silence by this combination of noises, started to make up for lost time on arriving in the street once more.

“A thoroughly unpleasant neighbourhood,” he said, critically surveying the dark streets. “I fear me, Comrade Windsor, that we have been somewhat rash in venturing as far into the middle west as this. If ever there was a blighted locality where low-browed desperadoes might be expected to spring with whoops of joy from every corner, this blighted locality is that blighted locality. But we must carry on. In which direction, should you say, does this arena lie?”

It had begun to rain as they left Billy’s lodgings. Psmith turned up the collar of his Burberry.

“We suffer much in the cause of Literature,” he said. “Let us inquire of this genial soul if he knows where the Highfield is.”

The pedestrian referred to proved to be going there himself. They went on together, Psmith courteously offering views on the weather and forecasts of the success of Kid Brady in the approaching contest.

Rattling on, he was alluding to the prominent part Cosy Moments had played in the affair, when a rough thrust from Windsor’s elbow brought home to him his indiscretion.

He stopped suddenly, wishing he had not said as much. Their connection with that militant journal was not a thing even to be suggested to casual acquaintances, especially in such a particularly ill-lighted neighbourhood as that through which they were now passing.

Their companion, however, who seemed to be a man of small speech, made no comment. Psmith deftly turned the conversation back to the subject of the weather, and was deep in a comparison of the respective climates of England and the United States, when they turned a corner and found themselves opposite a gloomy, barn-like building, over the door of which it was just possible to decipher in the darkness the words “Highfield Athletic and Gymnastic Club.”

The tickets which Billy Windsor had obtained from his newspaper friend were for one of the boxes. These proved to be sort of sheep-pens of unpolished wood, each with four hard chairs in it. The interior of the Highfield Athletic and Gymnastic Club was severely free from anything in the shape of luxury and ornament. Along the four walls were raised benches in tiers. On these were seated as tough-looking a collection of citizens as one might wish to see. On chairs at the ring-side were the reporters, with tickers at their sides, by means of which they tapped details of each round through to their down-town offices, where write-up reporters were waiting to read off and elaborate the messages. In the centre of the room, brilliantly lighted by half a dozen electric chandeliers, was the ring.

There were preliminary bouts before the main event. A burly gentleman in shirt-sleeves entered the ring, followed by two slim youths in fighting costume and a massive person in a red jersey, blue serge trousers, and yellow braces, who chewed gum with an abstracted air throughout the proceedings.

The burly gentleman gave tongue in a voice that cleft the air like a cannon-ball.

“Ex-hib-it-i-on four-round bout between Patsy Milligan and Tommy Goodley, members of this club. Patsy on my right, Tommy on my left. Gentlemen will kindly stop smokin’.”

The audience did nothing of the sort. Possibly they did not apply the description to themselves. Possibly they considered the appeal a mere formula. Somewhere in the background a gong sounded, and Patsy, from the right, stepped briskly forward to meet Tommy, approaching from the left.

The contest was short but energetic. At intervals the combatants would cling affectionately to one another, and on these occasions the red-jerseyed man, still chewing gum and still wearing the same air of being lost in abstract thought, would split up the mass by the simple method of ploughing his way between the pair. Towards the end of the first round Thomas, eluding a left swing, put Patrick neatly to the floor, where the latter remained for the necessary ten seconds.

The remaining preliminaries proved disappointing. So much so that in the last of the series a soured sportsman on one of the benches near the roof began in satirical mood to whistle the “Merry Widow Waltz.” It was here that the red-jerseyed thinker for the first and last time came out of his meditative trance. He leaned over the ropes, and spoke—without heat, but firmly.

“If that guy whistling back up yonder thinks he can do better than these boys, he can come right down into the ring.”

The whistling ceased.

There was a distinct air of relief when the last preliminary was finished and preparations for the main bout began. It did not commence at once. There were formalities to be gone through, introductions and the like. The burly gentleman reappeared from nowhere, ushering into the ring a sheepishly-grinning youth in a flannel suit.

“In-ter-doo-cin’ Young Leary,” he bellowed impressively, “a noo member of this club, who will box some good boy here in September.”

He walked to the other side of the ring and repeated the remark. A raucous welcome was accorded to the new member.

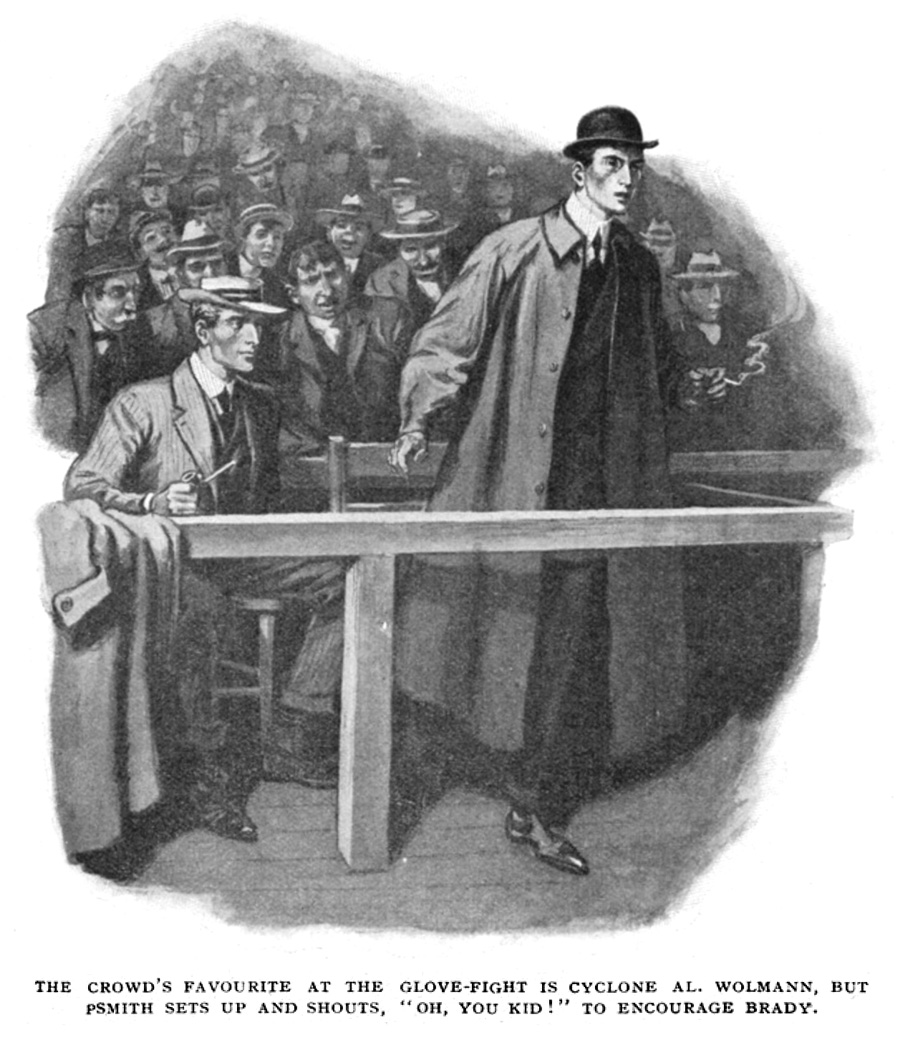

Two other notable performers were introduced in a similar manner, and then the building became suddenly full of noise, for a tall youth in a bath-robe, attended by a little army of assistants, had entered the ring. One of the army carried a bright green bucket, on which were painted in white letters the words “Cyclone Al. Wolmann.” A moment later there was another, though a far lesser, uproar, as Kid Brady, his pleasant face wearing a self-conscious smirk, ducked under the ropes and sat down in the opposite corner.

“Ex-hib-it-i-on ten-round bout,” thundered the burly gentleman, “between Cyclone Al. Wolmann——”

Loud applause. Mr. Wolmann was one of the famous, a fighter with a reputation from New York to San Francisco. He was generally considered the most likely man to give the hitherto invincible Jimmy Garvin a hard battle for the light-weight championship.

“Oh, you Al.!” roared the crowd.

Mr. Wolmann bowed benevolently.

“——and Kid Brady, members of this——”

There was noticeably less applause for the Kid. He was an unknown. A few of those present had heard of his victories in the West, but these were but a small section of the crowd. When the faint applause had ceased, Psmith rose to his feet.

“Oh, you Kid!” he observed encouragingly. “I should not like Comrade Brady,” he said, re-seating himself, “to think that he has no friend but his poor old mother, as, you will recollect, occurred on a previous occasion.”

The burly gentleman, followed by the two armies of assistants, dropped down from the ring, and the gong sounded.

Mr. Wolmann sprang from his corner as if somebody had touched a spring. He seemed to be of the opinion that if you are a cyclone, it is never too soon to begin behaving like one. He danced round the Kid with an india-rubber agility. The Cosy Moments representative exhibited more stolidity. Except for the fact that he was in fighting attitude, with one gloved hand moving slowly in the neighbourhood of his stocky chest, and the other pawing the air on a line with his square jaw, one would have said that he did not realise the position of affairs. He wore the friendly smile of the good-natured guest who is led forward by his hostess to join in some round game.

Suddenly his opponent’s long left shot out. The Kid, who had been strolling forward, received it under the chin, and continued to stroll forward as if nothing of note had happened. He gave the impression of being aware that Mr. Wolmann had committed a breach of good taste and of being resolved to pass it off with ready tact.

The Cyclone, having executed a backward leap, a forward leap, and a feint, landed heavily with both hands. The Kid’s genial smile did not even quiver, but he continued to move forward. His opponent’s left flashed out again, but this time, instead of ignoring the matter, the Kid replied with a heavy right swing; and Mr. Wolmann, leaping back, found himself against the ropes. By the time he had got out of that uncongenial position, two more of the Kid’s swings had found their mark. Mr. Wolmann, somewhat perturbed, scuttered out into the middle of the ring, the Kid following in his self-contained, solid way.

The Cyclone now became still more cyclonic. He had a left arm which seemed to open out in joints like a telescope. Several times when the Kid appeared well out of distance there was a thud as a brown glove ripped in over his guard and jerked his head back. But always he kept boring in, delivering an occasional right to the body with the pleased smile of an infant destroying a Noah’s Ark with a tack-hammer. Despite these efforts, however, he was plainly getting all the worst of it. Energetic Mr. Wolmann, relying on his long left, was putting in three blows to his one. When the gong sounded, ending the first round, the house was practically solid for the Cyclone. Whoops and yells rose from everywhere. The building rang with shouts of, “Oh, you Al.!”

Psmith turned sadly to Billy.

“It seems to me, Comrade Windsor,” he said, “that this merry meeting looks like doing Comrade Brady no good. I should not be surprised at any moment to see his head bounce off on to the floor.”

“Wait,” said Billy. “He’ll win yet.”

“You think so?”

“Sure. He comes from Wyoming,” said Billy with simple confidence.

Rounds two and three were a repetition of round one. The Cyclone raged almost unchecked about the ring. In one lightning rally in the third he brought his right across squarely on to the Kid’s jaw. It was a blow which should have knocked any boxer out. The Kid merely staggered slightly, and returned to business, still smiling.

“See!” roared Billy enthusiastically in Psmith’s ear, above the uproar. “He doesn’t mind it! He likes it! He comes from Wyoming!”

With the opening of round four there came a subtle change. The Cyclone’s fury was expending itself. That long left shot out less sharply. Instead of being knocked back by it, the Cosy Moments champion now took the hits in his stride, and came shuffling in with his damaging body-blows. There were cheers and “Oh, you Al.s!” at the sound of the gong, but there was an appealing note in them this time. The gallant sportsmen whose connection with boxing was confined to watching other men fight and betting on what they considered a certainty, and who would have expired promptly if any one had tapped them sharply on their well-filled waistcoats, were beginning to fear that they might lose their money after all.

In the fifth round the thing became a certainty. Like the month of March, the Cyclone, who had come in like a lion, was going out like a lamb. A slight decrease in the pleasantness of the Kid’s smile was noticeable. His expression began to resemble more nearly the gloomy importance of the Cosy Moments photographs. Yells of agony from panic-stricken speculators around the ring began to smite the rafters. The Cyclone, now but a gentle breeze, clutched repeatedly, hanging on like a leech till removed by the red-jerseyed referee.

Suddenly a grisly silence fell upon the house. It was broken by a cow-boy yell from Billy Windsor. For the Kid, battered, but obviously content, was standing in the middle of the ring, while on the ropes the Cyclone, drooping like a wet sock, was sliding slowly to the floor.

“Cosy Moments wins,” said Psmith. “An omen, I fancy, Comrade Windsor.”

CHAPTER XV.

an addition to the staff.

ENETRATING into the Kid’s dressing-room some moments later,

the editorial staff found the winner of the ten-round exhibition bout between

members of the club seated on a chair, having his right leg rubbed by a shock-headed man in a sweater, who had been one of his seconds during the conflict.

The Kid beamed as they entered.

ENETRATING into the Kid’s dressing-room some moments later,

the editorial staff found the winner of the ten-round exhibition bout between

members of the club seated on a chair, having his right leg rubbed by a shock-headed man in a sweater, who had been one of his seconds during the conflict.

The Kid beamed as they entered.

“Gents,” he said, “come right in. Mighty glad to see you.”

“It is a relief to me, Comrade Brady,” said Psmith, “to find that you can see us. I had expected to find that Comrade Wolmann’s purposeful biffs had completely closed your star-likes.”

“Sure, I never felt them. He’s a good quick boy, is Al., but,” continued the Kid with powerful imagery, “he couldn’t hit a hole in a block of ice-cream, not if he was to use a hammer.”

“And yet at one period in the proceedings, Comrade Brady,” said Psmith, “I fancied that your head would come unglued at the neck. But the fear was merely transient. When you began to administer those—am I correct in saying?—half-scissor hooks to the body, why, then I felt like some watcher of the skies when a new planet swims into his ken; or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes he stared at the Pacific.”

The Kid blinked.

“How’s that?” he inquired.

“And why did I feel like that, Comrade Brady? I will tell you. Because my faith in you was justified. Because there before me stood the ideal fighting-editor of Cosy Moments. It is not a post that any weakling can fill. Mere charm of manner cannot qualify a man for the position. No one can hold down the job simply by having a kind heart or being good at farmyard imitations. No. We want a man of thews and sinews, a man who would rather be hit on the head with a half-brick than not. And you, Comrade Brady, are such a man.”

The Kid turned appealingly to Billy.

“Say, this gets past me, Mr. Windsor. Put me wise.”

“Can we have a couple of words with you alone, Kid?” said Billy. “We want to talk over something with you.”

“Sure. Sit down, gents. Jack’ll be through in a minute.”

Jack, who during this conversation had been concentrating himself on his subject’s left leg, now announced that he guessed that would about do, and having advised the Kid not to stop and pick daisies, but to get into his clothes at once before he caught a chill, bade the company good-night and retired.

Billy shut the door.

“Kid,” he said, “You know those articles about the tenements we’ve been having in the paper?”

“Sure. I read ’em. They’re to the good.”

Psmith bowed.

“You stimulate us, Comrade Brady. This is praise from Sir Hubert Stanley.”

“It was about time some strong josher came and put it across to ’em,” added the Kid.

“So we thought. Comrade Parker, however, totally disagreed with us.”

“Parker?”

“That’s what I’m coming to,” said Billy. “The day before yesterday a man named Parker called at the office and tried to buy us off.”

Billy’s voice grew indignant at the recollection.

“You gave him the hook, I guess?” queried the interested Kid.

“To such an extent, Comrade Brady,” said Psmith, “that he left breathing threatenings and slaughter. And it is for that reason that we have ventured to call upon you.”

“It’s this way,” said Billy. “We’re pretty sure by this time that whoever the man is this fellow Parker’s working for has put one of the gangs on to us.”

“You don’t say!” exclaimed the Kid. “Gum! Mr. Windsor, they’re tough propositions, those gangs.”

“We’ve been followed in the streets, and once they put up a bluff to get us where they could do us in. So we’ve come along to you. We can look after ourselves out of the office, you see, but what we want is some one to help in case they try to rush us there.”

“In brief, a fighting-editor,” said Psmith. “At all costs we must have privacy. No writer can prune and polish his sentences to his satisfaction if he is compelled constantly to break off in order to eject boisterous hooligans. We therefore offer you the job of sitting in the outer room and intercepting these bravoes before they can reach us. The salary we leave to you. There are doubloons and to spare in the old oak chest. Take what you need and put the rest—if any—back. How does the offer strike you, Comrade Brady?”

“We don’t want to get you in under false pretences, Kid,” said Billy. “Of course, they may not come anywhere near the office. But still, if they did, there would be something doing. What do you feel about it?”

“Gents,” said the Kid, “it’s this way.”

He stepped into his coat, and resumed.

“Now that I’ve made good by getting the decision over Al., they’ll be giving me a chance of a big fight. Maybe with Jimmy Garvin. Well, if that happens, see what I mean? I’ll have to be going away somewhere and getting into training. I shouldn’t be able to come and sit with you. But, if you gents feel like it, I’d be mighty glad to come in till I’m wanted to go into training-camp.”

“Great,” said Billy; “that would suit us all the way up. If you’d do that, Kid, we’d be tickled to death.”

“And touching salary——” put in Psmith.

“Shucks!” said the Kid with emphasis. “Nix on the salary thing. I wouldn’t take a dime. If it hadn’t a-been for you gents, I’d have been waiting still for a chance of lining up in the championship class. That’s good enough for me. Any old thing you gents want me to do, I’ll do it. And glad, too.”

“Comrade Brady,” said Psmith warmly, “You are, if I may say so, the goods. You are, beyond a doubt, supremely the stuff. We three, then, hand-in-hand, will face the foe; and if the foe has good, sound sense, he will keep right away. You appear to be ready. Shall we meander forth?”

The building was empty and the lights were out when they emerged from the dressing-room. They had to grope their way in darkness. It was still raining when they reached the street, and the only signs of life were a moist policeman and the distant glare of public-house lights down the road.

They turned off to the left, and, after walking some hundred yards, found themselves in a blind alley.

“Hullo!” said Billy. “Where have we come to?”

Psmith sighed.

“In my trusting way,” he said, “I had imagined that either you or Comrade Brady was in charge of this expedition and taking me by a known route to the nearest Subway station. I did not think to ask. I placed myself, without hesitation, wholly in your hands.”

“I thought the Kid knew the way,” said Billy.

“I was just taggin’ along with you gents,” protested the light-weight, “I thought you was taking me right. This is the first time I been up here.”

“Next time we three go on a little jaunt anywhere,” said Psmith resignedly, “it would be as well to take a map and a corps of guides with us. Otherwise we shall start for Broadway and finish up at Minneapolis.”

They emerged from the blind alley and stood in the dark street, looking doubtfully up and down it.

“Aha!” said Psmith suddenly, “I perceive a native. Several natives, in fact. Quite a little covey of them. We will put our case before them, concealing nothing, and rely on their advice to take us to our goal.”

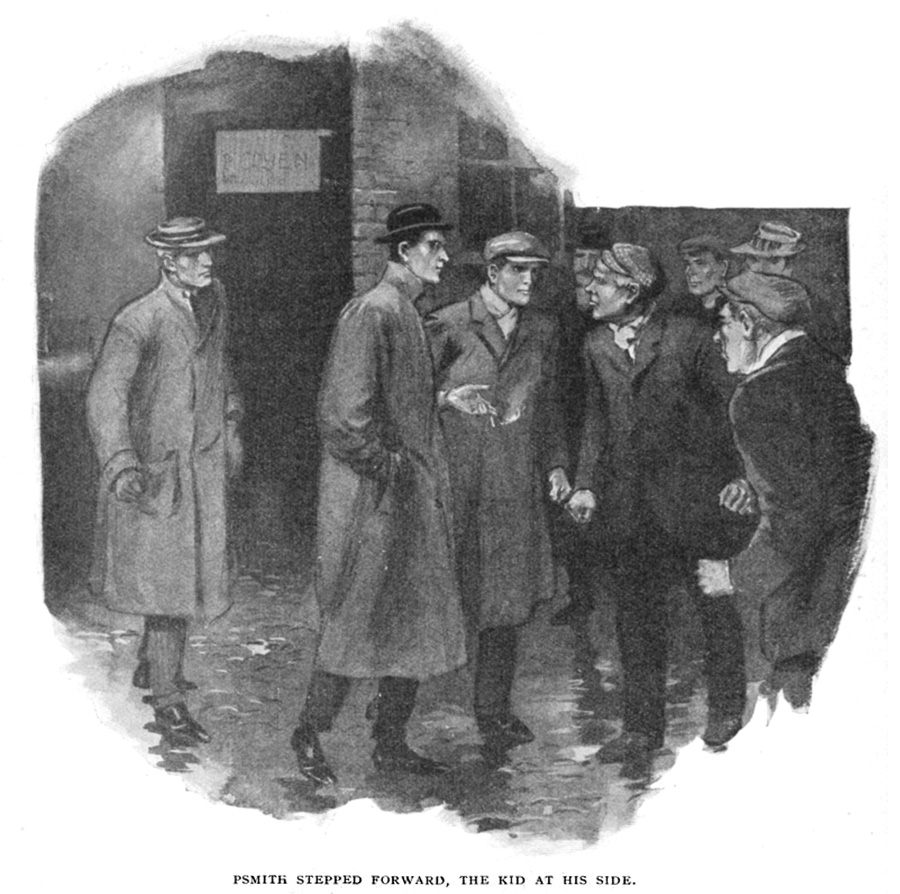

A little knot of men was approaching from the left. In the darkness it was impossible to say how many of them there were. Psmith stepped forward, the Kid at his side.

“Excuse me, sir,” he said to the leader, “but if you can spare me a moment of your valuable time——”

There was a sudden shuffle of feet on the pavement, a quick movement on the part of the Kid, a chunky sound as of wood striking wood, and the man Psmith had been addressing fell to the ground in a heap.

As he fell, something dropped from his hand on to the pavement with a bump and a rattle. Stooping swiftly, the Kid picked it up, and handed it to Psmith. His fingers closed upon it. It was a short, wicked-looking little bludgeon, the black-jack of the New York tough.

“Get busy,” advised the Kid briefly.

(To be continued)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums