The Circle, March 1909

Chapter XXI

The Calm Before the Storm

EALE,”

I said, “what on earth do you mean?

Where have they gone?”

EALE,”

I said, “what on earth do you mean?

Where have they gone?”

“Don’t know, sir. London, I expect.”

“When did they go? Oh, you told me that. Didn’t they say why they were going?”

“No, sir.”

We looked at one another.

“Beale,” I said.

“Sir?”

“Do you know what I think?”

“Yes, sir.”

“They’ve bolted.”

“So I says to the missus, sir. It struck me right off, in a manner of speaking.”

“This is awful,” I said.

“Yes, sir.”

His face betrayed no emotion, but he was one of those men whose expression never varies. It’s a way they have in the army.Norman Murphy in his A Wodehouse Handbook cites an 1863 song, but I’ve found this phrase appearing in quotation marks as far back as 1836; I have not yet traced the original.

“This wants thinking out, Beale,” I said.

“Yes, sir.”

“You’d better ask Mrs. Beale to give me some dinner and then I’ll think it out.”

“Yes, sir.”

I was in an unpleasant position. As soon as the news got about that Ukridge had gone the deluge would begin. His creditors would abandon their passive tactics and take active steps. The siege of Port ArthurThe longest land battle of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 would be nothing to it.

I summoned Beale after dinner and held a council of war.

“Let’s see exactly how we stand,” I said. “My point is that I particularly wish to go on living down here for at least another fortnight. Of course, my position is simple. I am Mr. Ukridge’s guest. I shall go on living as I have been doing up to the present. He asked me down here to help him look after the fowls, so I shall go on looking after them. I shall want a chicken a day, I suppose, or, perhaps, two, for my meals, and there the thing ends, as far as I am concerned. Complications set in when we come to consider you and Mrs. Beale. There’s the matter of wages. Are yours in arrears?”

“Yes, sir. A month.”

“And Mrs. Beale’s the same, I suppose?”

“Yes, sir. A month.”

“H’m. Well, it seems to me, Beale, you can’t lose anything by stopping on.”

“I can’t be paid any less than I have bin, sir,” he agreed.

“Exactly. You might just as well stop on and help me in the fowl run. What do you think?”

“Very well, sir.”

“And Mrs. Beale will do the same?”

“Yes, sir.

“That’s excellent. You’re a hero, Beale. I shan’t forget you. There’s a check coming to me from a magazine in another week for a short story. When it arrives I’ll look into that matter of back wages. Tell Mrs. Beale I’m much obliged to her.”

“Yes, sir.”

Having concluded that delicate business I lit my pipe and strolled out into the garden with Bob.

It was abominable of Ukridge to desert me this way. Even if I had not been his friend, it would have been bad. The fact that we had known each other for years made it doubly discreditable. He might at least have warned me, and given me the option of leaving the sinking ship with him.

I did not go to bed till late that night. There was something so peaceful in the silence that brooded over everything that I stayed on enjoying it. Perhaps it struck me as all the more peaceful because I could not help thinking of the troublous times that were to come. Already I seemed to hear the horrid roar of a herd of infuriated creditors. I seemed to see fierce brawlings and sackings in progress in this very garden.

“It will be a coarse, brutal spectacle, Robert,” I said.

Bob uttered a little whine, as if he, too, were endowed with powers of prophecy.

Chapter XXII

The Storm Breaks

RATHER to my surprise the next morning passed off uneventfully. By lunch time I had come to the conclusion that the expected trouble would not occur that day and I felt that I might well leave my post for the afternoon while I went to the Professor’s to pay my respects.

The Professor was out when I arrived. Phyllis was in, and as we had a good many things of no importance to say to each other it was not till the evening that I started for the farm again.

As I approached the sound of voices smote my ears.

I stopped. I could hear Beale speaking. Then came the rich notes of Vickers, the butcher. Then Beale again. Then Dawlish, the grocer. Then a chorus.

The storm had burst, and in my absence.

I blushed for myself. I was in command, and I had deserted the fort in time of need. What must the faithful hired man be thinking of me? Probably he placed me, as he had placed Ukridge, in the ragged ranks of those who have shot the moon.

Fortunately, having just come from the Professor’s, I was in the costume which of all my wardrobe was most calculated to impress. To a casual observer I should probably suggest wealth and respectability. I opened the gate and strode in, trying to look as opulent as possible.

It was an animated scene that met my eyes. In the middle of the lawn stood the devoted Beale, a little more flushed than I had seen him hitherto, parleying with a burly and excited young man without a coat. Grouped round the pair were some dozen men, young, middle aged, and old, all talking their hardest. I could distinguish nothing of what they were saying. I noticed that Beale’s left cheek bone was a little discolored, and there was a hard, dogged expression on his face. He, too, was in his shirt sleeves.

There seemed to have been trouble already. Looking more closely I perceived sitting on the grass, apart, a second young man. His face was obscured by a dirty pocket handkerchief with which he dabbed tenderly at his features. Every now and then the shirt-sleeved young man flung his hand toward him with an indignant gesture, talking hard the while. It did not need a preternaturally keen observer to deduce what had happened. Beale must have fallen out with the young man who was sitting on the grass and smitten him, and now his friend had taken up the quarrel.

“Now this,” I said to myself, “is rather interesting. Here in this one farm we have the only three known methods of dealing with duns. Beale is evidently an exponent of the violent method. Ukridge is an apostle of evasion. I shall try conciliation. I wonder which of us will be the most successful.”

Meanwhile, not to spoil Beale’s efforts by allowing him too little scope for experiment, I refrained from making my presence known and continued to stand by the gate an interested spectator.

Things were evidently moving now. The young man’s gestures became more vigorous. The dogged look on Beale’s face deepened. The comments of the ring increased in point and pungency.

“What did you hit him for, then?”

This question was put, always in the same words and with the same air of quiet triumph, at intervals of thirty seconds by a little man in a snuff-colored suit with a purple tie. Nobody ever answered him or appeared to listen to him but he seemed each time to think that he had clinched the matter and cornered his opponent.

Other voices chimed in.

“You hit him, Charlie. Go on. You hit him.”

“We’ll have the law.”

“Go on, Charlie.”

Flushed with the favor of the many-headed, Charlie now proceeded from threats to action. His right fist swung round suddenly. But Beale was on the alert. He ducked sharply, and the next minute Charlie was sitting on the ground beside his fallen friend. A hush fell on the ring and the little man in the purple tie was left repeating his formula without support.

I advanced. It seemed to me that the time had come to be conciliatory. Charlie was struggling to his feet, obviously anxious for a second round, and Beale was getting into position once more. In another five minutes conciliation would be out of the question.

“What’s all this?” I said.

My advent caused a stir. Excited men left Beale and rallied round me. Charlie, rising to his feet, found himself dethroned from his position of man of the moment and stood blinking at the setting sun and opening and shutting his mouth. There was a buzz of conversation.

“Don’t all speak at once, please,” I said. “I can’t possibly follow what you say. Perhaps you will tell me what you want?”

I singled out a short, stout man in gray. He wore the largest whiskers ever seen on human face.

“It’s like this, sir. We all of us want to know where we are.”

“I can tell you that,” I said, “you’re on our lawn, and I should be much obliged if you would stop digging your heels into it.”

This was not, I suppose, conciliation in the strictest and best sense of the word, but the thing had to be said.

“You don’t understand me, sir,” he said, excitedly. “When I said we didn’t know where we were it was a manner of speaking. We want to know how we stand.”

“On your heels,” I replied, gently, “as I pointed out before.”

“I am Brass, sir, of Axminster. My account with Mr. Ukridge is ten pounds eight shillings and fourpence. I want to know——”

The whole strength of the company now joined in.

“You know me, Mr. Garnet. Appleby, in the High——” (voice lost in the general roar) “ . . . and eightpence.”

“My account with Mr. Uk . . .”

“ . . . settle . . .”

“I represent Bodger . . .”

A diversion occurred at this point. Charlie, who had long been eying Beale sourly, dashed at him with swinging fists and was knocked down again. The whole trend of the meeting altered once more. Conciliation became a drug. Violence was what the public wanted. Beale had three fights in rapid succession. I was helpless. Instinct prompted me to join the fray but prudence told me that such a course would be fatal.

At last, in a lull, I managed to catch the Hired Retainer by the arm as he drew back from the prostrate form of his latest victim.

“Drop it, Beale,” I whispered, hotly—“drop it. We shall never manage these people if you knock them about. Go indoors and stay there while I talk to them.”

“But if they goes for you, sir, and tries to wipe the face off you?”

“They won’t—they won’t. If they do I’ll shout for you.”

He went reluctantly into the house and I turned again to my audience.

“If you will kindly be quiet for a moment——” I said.

“I am Appleby, Mr. Garnet, in the High Street. Mr. Ukridge——”

“Eighteen pounds fourteen shillings——”

“Kindly glance——”

I waved my hands wildly above my head.

“Stop! stop! stop!” I shouted.

The babble continued, but diminished gradually in volume. Through the trees, as I waited, I caught a glimpse of the sea. I wished I was out on the Cob, where, beyond these voices, there was peaceTennyson, last line of “Guinevere” in Idylls of the King. My head was beginning to ache and I felt faint for want of food.

“Gentlemen——” I cried, as the noise died away.

The latch of the gate clicked. I looked up and saw a tall, thin young man in a frock coat and silk hat enter the garden. It was the first time I had seen the costume in the country.

He approached me.

“Mr. Ukridge, sir?” he said.

“My name is Garnet. Mr. Ukridge is away at the moment.”

“I come from Whiteley’s, Mr. Garnet. Our Mr. Blenkinsop having written on several occasions to Mr. Ukridge, calling his attention to the fact that his account has been allowed to mount to a considerable figure, and having received no satisfactory reply, desired me to visit him. I am sorry that he is not at home.”

“So am I,” I said, with feeling.

“Do you expect him to return shortly?”

“No,” I said, “I do not.”

He was looking curiously at the expectant band of duns. I forestalled his question.

“Those are some of Mr. Ukridge’s creditors,” I said. “I am just about to address them. Perhaps you will take a seat. The grass is quite dry. My remarks will embrace you as well as them.”

Comprehension came into his eyes, and the natural man in him peeped through the polish.

“Great Scott, has he done a bunk?” he cried.

“To the best of my knowledge, yes,” I said.

He whistled.

I turned again to the local talent.

“Gentlemen——” I shouted.

“Hear, hear,” said some idiot.

“Gentlemen, I intend to be quite frank with you. We must decide just how matters stand between us. (A voice, “Where’s Ukridge?”) Mr. Ukridge left for London suddenly (bitter laughing) yesterday afternoon. Personally, I think he will come back very shortly.”

Hoots of derision greeted this prophecy.

I resumed.

“I fail to see your object in coming here. I have nothing for you. I couldn’t pay your bills if I wanted to.”

It began to be borne in upon me that I was becoming unpopular.

“I am here simply as Mr. Ukridge’s guest,” I proceeded. After all, why should I spare the man? “I have nothing whatever to do with his business affairs. I refuse absolutely to be regarded as in any way indebted to you. I am sorry for you. You have my sympathy. That is all I can give you, sympathy—and good advice.”

Dissatisfaction. I was getting myself disliked. And I had meant to be so conciliatory, to speak to these unfortunates words of cheer which should be as olive oil poured into a wound. For I really did sympathize with them. I considered that Ukridge had used them disgracefully. But I was irritated. My head ached abominably.

“Then am I to tell our Mr. Blenkinsop,” asked the frock-coated one, “that the money is not and will not be forthcoming?”

“When next you smoke a quiet cigar with your Mr. Blenkinsop,” I replied, courteously, “and find conversation flagging, I rather think I should say something of the sort.”

“We shall, of course, instruct our solicitors at once to institute legal proceedings against your Mr. Ukridge.”

“Don’t call him my Mr. Ukridge. You can do whatever you please.”

“That is your last word on the subject?”

“I hope so.”

“Where’s our money?” demanded a discontented voice from the crowd.

Then Charlie, filled with the lust of revenge, proposed that the company should sack the place.

“We can’t see the color of our money,” he said, pithily, “but we can have our own back.”

That settled it. The battle was over. The most skilful general must sometimes recognize defeat. I could do nothing further with them. I had done my best for the farm. I could do no more.

I lit my pipe and strolled into the paddock.

Chaos followed. Indoors and out of doors they raged without check. Even Beale gave the thing up. He knocked Charlie into a flower bed and then disappeared in the direction of the kitchen.

Presently out came the invaders with their loot, some with pictures, others with bric-à-brac, sofa cushions, chairs, rugs; one bore the gramaphone. Then I heard somebody—Charlie, again, it seemed to me—propose a raid on the fowl run.

The fowls had had their moments of unrest since they had been our property, but what they had gone through with us was peace compared with what befell them then. Not even on that second evening of our visit, when we had run unmeasured miles in pursuit of them, had there been such confusion. Roused abruptly from their beauty sleep they fled in all directions. The summer evening was made hideous with the noise of them.

“Disgraceful, sir. Is it not disgraceful!” said a voice at my ear.

The young man from Whiteley’s stood beside me. He did not look happy. His forehead was damp. Somebody seemed to have stepped on his hat and his coat was smeared with mold.

I was turning to answer him when from the dusk in the direction of the house came a sudden roar. A passionate appeal to the world in general to tell the speaker what all this meant.

There was only one man of my acquaintance with a voice like that. I walked without hurry toward him.

“Good evening, Ukridge,” I said.

Chapter XXIII

After the Storm

A YELL of welcome drowned the tumult of the looters.

“Is that you, Garny, old horse? What’s up? What’s the matter? Has everybody gone mad? Who are those blackguardly scoundrels in the fowl run? What are they doing? What’s been happening?”

“I have been entertaining a little meeting of your creditors,” I said. “And now they are entertaining themselves.”

“But what did you let them do it for?”

“What is one among so many?” I said.

“Oh,” moaned Ukridge, as a hen flashed past us, pursued by the whiskered criminal, “it’s a little hard. I can’t go away for a day——”

“You can’t,” I said. “You’re right there. You can’t go away without a word——”

“Without a word? What do you mean? Garny, old boy, pull yourself together. You’re overexcited. Do you mean to tell me you didn’t get my note?”

“What note?”

“The one I left on the dining-room table.”

“There was no note there.”

“What!”

I was reminded of the scene that had taken place on the first day of our visit.

“Feel in your pockets,” I said.

And history repeated itself. One of the first things he pulled out was the note.

“Why, here it is!” he said, in amazement.

“Of course. Where did you expect it to be? Was it important?”

“Why, it explained the whole thing.”

“Then,” I said, “I wish you’d let me read it. A note that can explain what’s happened ought to be worth reading.”

I took the envelope from his hand and opened it.

It was too dark to read, so I lit a match. A puff of wind extinguished it. There is always just enough wind to extinguish a match.

I pocketed the note.

“I can’t read it now,” I said. “Tell me what it was about.”

“It was telling you to sit tight and not to worry about us going away, because we should be back in a day or two.”

“That’s good about worrying. You’re a thoughtful chap, Ukridge. And what sent you up to town?”

“Why, we went to touch Millie’s Aunt Elizabeth.”

A light began to shine on my darkness.

“Oh!” I said.

“You remember Aunt Elizabeth? We got a letter from her not so long ago.”

“I know whom you mean. She called you a gaby.”

“And a guffin.”

“Of course. I remember thinking her a shrewd and discriminating old lady, with a great gift of description. So you went to touch her?”

“That’s it. I suddenly found that things were getting into an A 1 tangle, and that we must have more money. So we went off together, looked her up at her house, stated our painful case and corraled the guineas. Millie and I shared the work. She did the asking, while I inquired after the rheumatism. She mentioned the precise figure that would clear us. I patted the toy Pomeranian. Little beast. Got after me quick when I wasn’t looking and chewed my ankle.”

“Thank Heaven for that,” I said.

“In the end Millie got the money and I got the home truths. Millie’s an angel.”

“Of course she is,” said I.

Mrs. Ukridge joined us shortly afterward. She had been exploring the house and noting the damage done. Her eyes were open to their fullest extent as she shook hands with me.

“Oh, Mr. Garnet,” she said, “couldn’t you have stopped them?”

I felt a cur. Had I done as much as I might have done to stem the tide?

“I’m awfully sorry, Mrs. Ukridge,” I said. “I really don’t think I could have done more. We tried every method. Beale had seven fights and I made a speech on the lawn, but it was all no good.

“Perhaps we can collect these men and explain things,” I added. “I don’t believe any of them know you’ve come back.”

“Beale,” said Ukridge, “go round the place and tell those blackguards that I’ve come back and would like to have a word with them on the lawn. And if you find any of them stealing my fowls knock them down.”

“I ’ave knocked down one or two,” said Beale, with approval. “That Charlie——”

“That’s right, Beale. You’re an excellent man and I will pay you your back wages to-night before I go to bed.”

“Those fellers, sir,” said Beale, having expressed his gratification, “they’ve bin and scattered most of them birds already, sir.”

Ukridge groaned.

“Demons!” he said.

Beale went off.

The audience assembled on the lawn in the moonlight. Ukridge, with his cap well over his eyes and his mackintosh hanging around him like a Roman toga, surveyed them stonily, and finally began his speech.

“You—you—you—you blackguards!” he said.

I always like to think of Ukridge as he appeared at that moment. There have been times when his conduct did not recommend itself to me. It has sometimes happened that I have seen flaws in him. But on this occasion he was at his best. He was eloquent. He dominated his audience.

He poured scorn upon his hearers and they quailed. He flung invective at them and they wilted.

It was hard, he said, it was a little hard, that a gentleman could not run up to London for a couple of days on business without having his private grounds turned upside down. He had intended to deal well by the tradesmen of the town, to put business in their way, to give them large orders. But would he? Not much. As soon as ever the sun had risen and another day begun their miserable accounts should be paid in full and their connection with him be cut off. Afterward it was probable that he would institute legal proceedings against them for trespass and damage to property, and if they didn’t all go to prison they might consider themselves uncommonly lucky, and if they didn’t fly the spot within the brief space of two ticks he would get among them with a shotgun. He was sick of them. They were no gentlemen, but cads. Scoundrels. Creatures that it would be rank flattery to describe as human beings. That’s the sort of things they were. And now they might go—quick!

The meeting then dispersed, without the usual vote of thanks.

We were quiet at the farm that night. Ukridge sat like Marius among the ruins of Carthage and refused to speak. Eventually he took Bob with him and went for a walk.

Half an hour later I, too, wearied of the scene of desolation. My errant steps took me in the direction of the sea. As I approached I was aware of a figure standing in the moonlight, gazing moodily out over the waters. Beside the figure was a dog.

I would not disturb his thoughts. The dark moments of massive minds are sacred. I forebore to speak to him. As readily might one of the generals of the Grand Army have opened conversation with Napoleon during the retreat from Moscow.

I turned softly and walked the other way. When I looked back he was still there.

Epilogue

(Argument, from the Morning Post: “ . . . and graceful, wore a simple gown of stiff satin and old lace, and a heavy lace veil fell in soft folds over the shimmering skirt. A reception was subsequently held by Mrs. O’Brien, aunt of the bride, at her house in Ennismore Gardens.”)

IN THE SERVANTS’ HALL

The Cook: . . . And as pretty a wedding, Mr. Hill, as ever I did see.

The Butler: Indeed, Mrs. Minchley? And how did our niece look?

The Cook (closing her eyes in silent rapture): Well, there! Well, there! That lace! (In a burst of ecstasy) . . . Well, there!! Words can’t describe it, Mr. Hill.

The Butler: Indeed, Mrs. Minchley?

The Cook: And Miss Phyllis—Mrs.

Garnet, I should say—she was as calm as calm. And looking

beautiful as—well, there! Now, Mr. Garnet, he did

look nervous, if you like, and when the

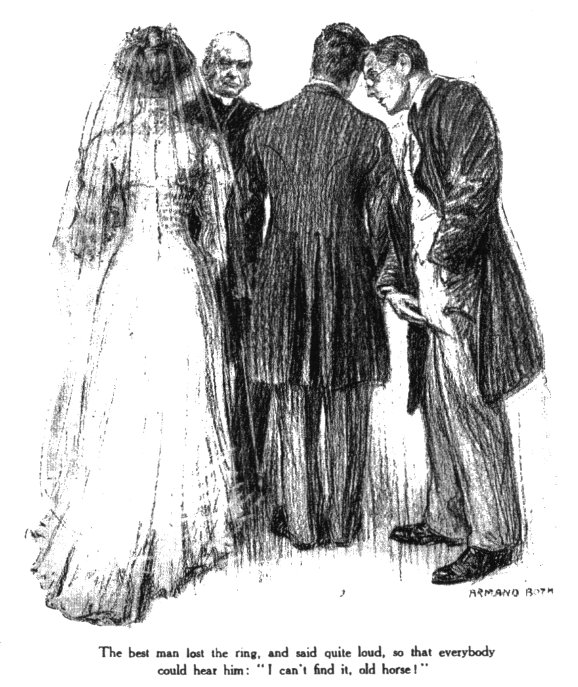

best man—such a queer-looking man, with pansnaypince-nez and a frock coat

that I wouldn’t have been best

man at a wedding in—when he lost the

ring and said, quite loud—every body could hear him: “I

can’t find it, old horse!” why, I did think Mr. Garnet would have fainted

away, and so I said to Jane, as was

sitting beside me. But he found it at the last moment and all went on as

merrily, as you may say, as a wedding-bell.

The Cook: And Miss Phyllis—Mrs.

Garnet, I should say—she was as calm as calm. And looking

beautiful as—well, there! Now, Mr. Garnet, he did

look nervous, if you like, and when the

best man—such a queer-looking man, with pansnaypince-nez and a frock coat

that I wouldn’t have been best

man at a wedding in—when he lost the

ring and said, quite loud—every body could hear him: “I

can’t find it, old horse!” why, I did think Mr. Garnet would have fainted

away, and so I said to Jane, as was

sitting beside me. But he found it at the last moment and all went on as

merrily, as you may say, as a wedding-bell.

Jane (sentimentally): Reely, these weddings, they do give you a sort of feeling, if you catch my meaning, Mrs. Minchley.

The Butler (with the air of a high priest who condescends for once to unbend and frolic with lesser mortals): Ah, it’ll be your turn next, Miss Jane.

Jane (who has long had designs on this dignified bachelor): Oh, Mr. Hill, reely! You do poke your fun. (Raises her eyes to his, and drops them swiftly, leaving him with a pleasant sensation of having said a good thing particularly neatly, and a growing idea that he might do worse than marry Jane, take a nice little house in Chelsea somewhere and let lodgings. He thinks it over.)

Tilby (a flighty young person who, when she has a moment or two to spare from the Higher Flirtation with the local policeman, puts in a little light work about the bedrooms): Oh, I say, this’ll be one in the eye for Riggetts, pore little feller. (Assuming an air of advanced melodrama): Ow! She ’as forsiken me! I’ll go and blow me little ’ead off with a blunderbuss! Ow, that one so fair could be so false!

Master Thomas Riggetts (the page boy, whose passion for the lady who has just become Mrs. Garnet has for many months been a by-word in the Servants’ Hall): Huh! (To himself, bitterly): Tike care, tike care, lest some day you drive me too far. (Is left brooding darkly.)

UPSTAIRS

The Bride: . . . Thank you . . . Oh, thank you . . . Thank you so much . . Thank you so much . . . Oh, thank you . . . Thank you . . . Thank you so much!

The Bridegroom: Thanks . . . Oh, thanks . . . Thanks awf’lly . . . Thanks awf’lly . . . Thanks awf’lly . . . Oh, thanks awf’lly . . . (with a brilliant burst of invention, amounting almost to genius): Thanks frightfully!

The Bride (to herself, rapturously): A-a-a-h!

The Bridegroom (dabbing at his forehead with his handkerchief during a lull): I shall drop.

The Best Man (appearing suddenly at his side, with a glass): Bellows to mend, old horse—what? Keep going. You’re doing fine. Bless you. Bless you. (Drifts away.)

Elderly Stranger (to bridegroom): Sir, I have jigged your wife on my knee.

The Bridegroom (with absent politeness): Ah? Lately?

Elderly Stranger: When she was a baby, sir.

The Bridegroom (from force of habit): Oh, thanks. Thanks awf’lly.

The Bride (to herself): Why can’t one get married every day? . . . (Catching sight of a young gentleman whose biweekly conversation with her in the past was wont to consist of two remarks on the weather and one proposal of marriage): Oh! Oh, what a shame inviting poor little Freddy Fraddle! Aunt Kathleen must have known! How could she be so cruel! Poor little fellow, he must be suffering dreadfully!

Poor Little Freddy Fraddle (addressing his immortal soul, as he catches sight of the bridegroom, with a set smile on his face, shaking hands with an Obvious Bore): Poor devil! poor, poor devil! And to think that I——! Well, well! There, but for the grace of God, goes Frederick Fraddle.

The Bridegroom (to the Obvious Bore): Thanks. Thanks, awf’lly.

The Obvious Bore (in measured tones): . . . are going, as you say, to Wales for your honeymoon, you should on no account miss the opportunity of seeing the picturesque ruins of Llanxwrg Castle, which are among the most prominent spectacles of Caernarvonshire, a county which I understand you to say you propose to include in your visit. The ruins are really part of the village of Twdyd-Prtsplgnd, but your best station would be Golgdn. There is a good train service to and from that spot. If you mention my name to the custodian of the ruins he will allow you to inspect the grave of the celebrated——

Immaculate Youth (interrupting): Hullo, Garnet, old man. Don’t know if you remember me. Latimer, of Oriel. I was a fresher in your third year. Gratters!

The Bridegroom (with real sincerity for once): Thanks. Thanks, awf’lly. (They proceed to talk Oxford shop together, to the exclusion of the O. B., who glides off in search of another victim.)

IN THE STREET

The Coachman (to his horse): Kim up, then!

The Horse (to itself): Dooce of a time these people are. Why don’t they hurry? I want to be off. I’m certain we shall miss that train.

The Best Man (to crowd of perfect strangers with whom in some mysterious way he has managed to strike up a warm friendship): Now, then, you men, stand by. Wait till they come out, then blaze away. Good handful first shot. That’s what you want.

The Cook (in the area, to Jane): Oh, I do ’ope they won’t miss that train, don’t you? Oh, here they come. Oh, don’t Miss Phyllis—Mrs. Garnet—look well, there. And I can remember her a little slip of a girl only so high, and she used to come to my kitchen and she used to say, “Mrs. Minchley,” she used to say—it seems only yesterday—“Mrs. Minchley, I want——”

(Left reminiscing.)

The Bride, as the page boy’s gloomy eye catches hers, “smiles as she was wont to smile.”

Master Riggetts (with a happy recollection of his latest-read work of fiction, “Sir Rupert of the Hall,” Meadowsweet Library—to himself): Good-by, proud lady. Fare you well. And may you never regret. May—you—nevorrr—regret!

(Dives passionately into larder and consoles himself with jam.)

The Best Man (to his gang of bravadoes): Now, then, you men, bang it in.

(They bang it in.)

The Bridegroom (retrieving his hat): Oh——

(Recollects himself in time.)

The Best Man: Oh shot, sir! Shot, indeed!

(The Bride and Bridegroom enter the carriage amid a storm of rice.)

The Best Man (coming to carriage window): Garny, old horse.

The Bridegroom: Well?

The Best Man: Just a moment. Look here, I’ve got a new idea. The best ever, ’pon my word it is. I’m going to start a duck farm and run it without water. What? You’ll miss your train? Oh, no, you won’t. There’s plenty of time. My theory is, you see, that ducks get thin by taking exercise and swimming about, and so on, don’t you know, so that if you kept them on land always they’d get jolly fat in about half the time—and no trouble and expense. See? What? You bring the missus down there. I’ll write you the address. Good-by. Bless you. Good-by, Mrs. Garnet.

| The Bride: The Bridegroom: | } |

(Simultaneously, with a smile apiece): Good-by. |

(They catch the train and live happily ever afterward.)

the end

Editor’s notes:

It’s a way they have in the army: Norman Murphy in his A Wodehouse Handbook cites an 1863 song, but I’ve found this phrase appearing in quotation marks as far back as 1836; I have not yet traced the original.

The siege of Port Arthur: The longest land battle of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05

where, beyond these voices, there was peace: Tennyson, last line of “Guinevere” in Idylls of the King

pansnay: pince-nez

—Notes by Neil Midkiff

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums