Collier’s Weekly, October 8, 1921

SALLY looked contentedly down the long table. She felt happy at last. Everybody was talking and laughing now, and her party, rallying after an uncertain start, was plainly the success she had hoped it would be. The first atmosphere of uncomfortable restraint, caused, she was only too well aware, by her brother Fillmore’s white evening waistcoat, had worn off; and the male and female patrons of Mrs. Meecher’s select boarding house (transient and residential) were themselves again.

At her end of the table the conversation had turned once more to the great vital topic of Sally’s legacy and what she ought to do with it. The next best thing to having money of one’s own is to dictate the spending of somebody else’s, and Sally’s guests were finding a good deal of satisfaction in arranging a budget for her. Rumor having put the sum at their disposal at a high figure, their suggestions had a certain spaciousness.

“Let me tell you,” said Augustus Bartlett briskly, “what I’d do if I were you.” Augustus Bartlett, who occupied an intensely subordinate position in the firm of Morris & Brown, the Wall Street brokers, always affected a brisk, incisive style of speech, as befitted a man in close touch with the great ones of finance. “I’d invest a couple of hundred thousand in some good safe bond issue—we’ve just put one out which you would do well to consider—and play about with the rest. When I say play about, I mean have a flutter in anything good that crops up. Multiple Steel’s worth looking at. They tell me it’ll be up to a hundred and fifty before next Saturday.”

Elsa Doland, the pretty girl with the big eyes who sat on Mr. Bartlett’s left, had other views. “Buy a theatre, Sally, and put on good stuff.”

“And lose every bean you’ve got,” said a mild young man, with a deep voice, across the table. “If I had a few hundred thousand,” said the mild young man, “I’d put every cent of it on Benny Whistler for the heavyweight championship. I’ve private information that Battling Tuke has been got at and means to lie down in the seventh—”

“Say, listen,” interrupted another voice, “lemme tell you what I’d do with four hundred thousand—”

“If I had four hundred thousand,” said Elsa Doland, “I know what would be the first thing I’d do.”

“What’s that?” Sally asked.

“Pay my bill for last week, due this morning.”

Sally got up quickly, and, flitting down the table, put her arm around her friend’s shoulder, and whispered in her ear: “Elsa darling, are you really broke? If you are, you know I’ll—”

Elsa Doland laughed.

“You are an angel, Sally. There’s no one like you. You’d give your last cent to anyone. Of course I’m not broke. I’ve just come back from the road, and I’ve saved a fortune. I only said that to draw you.”

SALLY returned to her seat, relieved, and found that the company had now divided itself into two schools of thought. The conservative and prudent element had definitely decided on three hundred thousand in Liberty Bonds and the rest in some safe real estate; while the smaller, more sporting section, impressed by the mild young man’s inside information, had already placed Sally’s money on Benny Whistler, doling it out cautiously in small sums so as not to spoil the market. The mild young man was confident that, if you went about the matter cannily and without precipitation, three to one might be obtained.

It seemed to Sally that the time had come to correct certain misapprehensions. “I don’t know where you got your figures,” she said, “but I’m afraid they’re wrong. I’ve just twenty-five thousand dollars.”

The statement had a chilling effect. To these jugglers with half millions the amount mentioned seemed for the moment almost too small to bother about. It was the sort of sum which they had been mentally setting aside for the heiress’s car fare. Then they managed to adjust their minds to it. After all, one could do something even with a pittance like twenty-five thousand.

“If I had twenty-five thousand,” said Augustus Bartlett, the first to rally from the shock, “I’d buy Amalgamated—”

“If I had twenty-five thousand—” began Elsa Doland.

“If I had had twenty-five thousand in the year nineteen hundred,” observed a gloomy-looking man with spectacles, “I could have started a revolution in Paraguay.”

He brooded somberly on what might have been.

“Well, I’ll tell you exactly what I’m going to do,” said Sally. “I’m going to start with a trip to Europe—France especially. I’ve heard France well spoken of. And after I’ve loafed there for a few weeks I’m coming back to look about and find some nice cozy little business which will let me put money into it and keep me in luxury. Are there any complaints?”

“Even a couple of thousand on Benny Whistler—” said the mild young man.

“I don’t want your Benny Whistler,” said Sally. “I wouldn’t have him if you gave him to me. If I want to lose my money, I’ll go to Monte Carlo and do it properly.”

“Monte Carlo!” said the gloomy man, brightening up at the magic name. “I was in Monte Carlo in the year ’97, and if I’d had another fifty dollars—just fifty—I’d have—”

AT the far end of the table there was a stir, a cough, and the grating of a chair on the floor; and slowly, with that easy grace which actors of the old school learned in the days when acting was acting, Mr. Maxwell Faucitt, the boarding house’s oldest inhabitant, rose to his feet.

“Ladies,” said Mr. Faucitt, bowing courteously, “and—” (ceasing to bow and casting from beneath his white and venerable eyebrows a quelling glance at certain male members of the boarding house’s younger set who were showing a disposition toward restiveness)—“gentlemen: I feel that I cannot allow this occasion to pass without saying a few words.”

His audience did not seem surprised. It was possible that life, always prolific of incident in a great city like New York, might some day produce an occasion which Mr. Faucitt would feel that he could allow to pass without saying a few words; but nothing of the sort had happened as yet, and they had given up hope. Right from the start of the meal they had felt that it would be optimism run mad to expect the old gentleman to abstain from a speech on the night of Sally Nicholas’s farewell dinner party; and, partly because they had braced themselves to it, but principally because Miss Nicholas’s hospitality had left them with a genial feeling of repletion, they settled themselves to listen with something resembling equanimity. A movement on the part of the Marvelous Murphys—new arrivals, who had been playing at Far Rockaway with their equilibristic act during the preceding week—to form a party of the extreme left and heckle the speaker, broke down under a cold look from their hostess. Brief though their acquaintance had been, both of these lissom young gentlemen admired Sally intensely.

And it should be set on record that this admiration of theirs was not misplaced. He would have been hard to please who had not been attracted by Sally. She was a small, trim, wisp of a girl with the tiniest of hands and feet, the friendliest of smiles, and a dimple that came and went in the curve of her rounded chin. Her eyes, which disappeared when she laughed, which was often, were a bright hazel; her hair a soft mass of brown. She had, moreover, a manner, an air of distinction lacking in the majority of Mrs. Meecher’s guests. And she carried Youth like a banner. In approving of Sally, the Marvelous Murphys had been guilty of no lapse from their high critical standard.

“I have been asked,” proceeded Mr. Faucitt, “though I am aware that there are others here far worthier of such a task—Brutuses compared with whom I, like Mark Antony, am no orator—I have been asked to propose the health—”

“Who asked you?” It was the smaller of the Marvelous Murphys who spoke. He was an unpleasant youth, snub-nosed and spotty. Still, he could balance himself with one hand on an inverted ginger-ale bottle while revolving a barrel on the soles of his feet. There is good in all of us.

“I have been asked,” repeated Mr. Faucitt, ignoring the unmannerly interruption—which, indeed, he would have found it hard to answer—“to propose the health of our charming hostess [applause], coupled with the name of her brother, our old friend Fillmore Nicholas.”

THE gentleman referred to, who sat at the speaker’s end of the table, acknowledged the tribute with a brief nod of the head. It was a nod of condescension; the nod of one who, conscious of being hedged about by social inferiors, nevertheless does his best to be not unkindly. And Sally, seeing it, debated in her mind for an instant the advisability of throwing an orange at her brother. There was one lying ready to her hand, and his glistening shirt front offered an admirable mark; but she restrained herself. After all, if a hostess yields to her primitive impulses, what happens? Chaos.

She leaned back with a sigh. The temptation had been hard to resist. A democratic girl, pomposity was a quality which she thoroughly disliked; and, though she loved him, she could not disguise it from herself that, ever since affluence had descended upon him some months ago, her brother Fillmore had become insufferably pompous. If there are any young men whom inherited wealth improves, Fillmore Nicholas was not one of them. He seemed to regard himself nowadays as a sort of Man of Destiny. To converse with him was for the ordinary human being like being received in audience by some more than ordinarily stand-offish monarch. It had taken Sally over an hour to persuade him to leave his apartment on Riverside Drive and revisit the boarding house for this special occasion; and, when he had come, he had entered wearing such faultless evening dress that he had made the rest of the party look like a gathering of tramp cyclists. His white waistcoat alone was a silent reproach to honest poverty and had caused an awkward constraint right through the soup and fish courses. Most of those present had known Fillmore Nicholas as an impecunious young man who could make a tweed suit last longer than one would have believed possible; they had called him “Fill” and helped him in more than usually lean times with small loans; but to-night they had eyed the waistcoat dumbly and shrunk back abashed.

“Speaking,” said Mr. Faucitt, “as an Englishman—for, though I have long since taken out what are technically known as my ‘papers,’ it was as a subject of the island kingdom that I first visited this great country—I may say that the two factors in American life which have always made the profoundest impression upon me have been the lavishness of American hospitality and the charm of the American girl. To-night we have been privileged to witness the American girl in the capacity of hostess, and I think I am right in saying, in asseverating, in committing myself to the statement that this has been a night which none of us present here will ever forget. Miss Nicholas has given us, ladies and gentlemen, a banquet. I repeat, a banquet. There has been alcoholic refreshment. I do not know where it came from; I do not ask how it was procured; but we have had it. Miss Nicholas—”

MR. FAUCITT paused to puff at his cigar. Sally’s brother Fillmore suppressed a yawn and glanced at his watch. Sally continued to lean forward raptly. She knew how happy it made the old gentleman to deliver a formal speech; and, though she wished the subject had been different, she was prepared to listen indefinitely.

“Miss Nicholas,” resumed Mr. Faucitt, lowering his cigar. “But why,” he demanded abruptly, “do I call her Miss Nicholas?”

“Because it’s her name,” hazarded the taller Murphy.

Mr. Faucitt eyed him with disfavor. He disapproved of the marvelous brethren—on general grounds, because, himself a resident of years’ standing, he considered that these transients from the vaudeville stage lowered the tone of the boarding house.

“Yes, sir,” he said severely, “it is her name. But she has another name, sweeter to those who love her, those who worship her, those who have watched her with the eye of sedulous affection through the three years she has spent beneath this roof—though that name,” said Mr. Faucitt, lowering the tone of his address and descending to what might almost be termed personalities, “may not be familiar to a couple of acrobats who have only been in the place a week-end and, thank Heaven, are going off to-morrow to infest some other city. That name,” said Mr. Faucitt, soaring once more to a loftier plane, “is Sally. Our Sally! For three years our Sally has flitted about this establishment like—I choose the simile advisedly—like a ray of sunshine. For three years she has made life for us a brighter, sweeter thing. And now a sudden access of worldly wealth, happily synchronizing with her twenty-first birthday, is to remove her from our midst. From our midst, ladies and gentlemen, but not from our hearts. And I think I may venture to hope, to prognosticate, that, whatever lofty sphere she may adorn in the future, to whatever heights in the social world she may soar, she will still continue to hold a corner in her own golden heart for the comrades of her Bohemian days. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you our hostess, Miss Sally Nicholas, coupled with the name of our old friend, her brother Fillmore.”

Sally, watching her brother heave himself to his feet as the cheers died away, felt her heart beat a little faster with anticipation. Fillmore was a fluent young man, once a power in his college debating society, and it was for that reason that she had insisted on his coming here to-night. She had guessed that Mr. Faucitt, the old dear, would say all sorts of delightful things about her, and she had mistrusted her ability to make a fitting reply. And it was imperative that a fitting reply should proceed from some one. She knew Mr. Faucitt so well. He looked on these occasions rather in the light of scenes from some play; and, sustaining his own part in them with such polished grace, was certain to be pained by anything in the nature of an anticlimax after he should have ceased to take the stage. Eloquent himself, he must be answered with eloquence, or his whole evening would be spoiled.

Fillmore spoke. “I’m sure,” said he, “you don’t want a speech. Very good of you to drink our health. Thank you.” He sat down.

THE effect of these few simple words on the company was marked, but not in every case identical. To the majority the emotion which they brought was one of unmixed relief. There had been something so menacing, so easy and practiced, in Fillmore’s attitude as he had stood there that the gloomier-minded had given him at least twenty minutes, and even the optimists had reckoned that they would be lucky if they got off with ten. As far as the bulk of the guests were concerned, there was no grumbling. Fillmore’s, to their thinking, had been the ideal after-dinner speech.

Far different was it with Mr. Maxwell Faucitt. The poor old man was wearing such an expression of surprise and dismay as he might have worn had somebody unexpectedly pulled the chair from under him. He was feeling the sick shock which comes to those who tread on a nonexistent last stair. And Sally, catching sight of his face, uttered a sharp, wordless exclamation as if she had seen a child fall down and hurt itself in the street. The next moment she had run round the table and was standing behind him with her arms round his neck. She spoke across him with a sob in her voice.

“My brother,” she stammered, directing a malevolent look at the immaculate Fillmore, who, avoiding her gaze, glanced down his nose and smoothed another wrinkle out of his waistcoat, “has not said quite—quite all I hoped he was going to say. I can’t make a speech, but”—Sally gulped—“but—I love you all and, of course, I shall never forget you, and—and—”

Here Sally kissed Mr. Faucitt and burst into tears.

“There, there!” said Mr. Faucitt soothingly.

The kindest critic could not have claimed that Sally had been eloquent; nevertheless Mr. Maxwell Faucitt was conscious of no sense of anticlimax. . . .

Sally had just finished telling her brother Fillmore what a pig he was. The lecture had taken place in the street outside the boarding house immediately on the conclusion of the festivities, when Fillmore, who had furtively collected his hat and overcoat and stolen forth into the night, had been overtaken and brought to bay by his justly indignant sister. Her remarks, punctuated at intervals by bleating sounds from the accused, had lasted some ten minutes.

As she paused for breath, Fillmore seemed to expand like an india-rubber ball which has been sat on. Dignified as he was to the world, he had never been able to prevent himself being intimidated by Sally when in one of these moods of hers. He regretted this, for it hurt his self-esteem, but he did not see how the fact could be altered. Sally had always been like that. Even the uncle, who after the death of their parents had become their guardian, had never, though a grim man, been able to cope successfully with Sally. In that last hectic scene three years ago, which had ended in their going out into the world together, the verbal victory had been hers. And it had been Sally who had achieved triumph in the one battle which Mrs. Meecher, apparently as a matter of duty, always brought about with each of her patrons in the first week of their stay. A sweet-tempered girl, Sally, like most women of a generous spirit, had cyclonic potentialities.

As she seemed to have said her say, Fillmore kept on expanding till he had reached the normal, when he ventured upon a speech for the defense.

“What have I done?” demanded Fillmore plaintively.

“Do you want to hear all over again?”

“No, no,” said Fillmore hastily. “But, listen, Sally, you don’t understand my position. You don’t seem to realize that all that sort of thing, all that boarding-house stuff, is a thing of the past. One’s got beyond it. One wants to drop it. One wants to forget it, darn it! Be fair. Look at it from my viewpoint. I’m going to be a big man—”

“You’re going to be a fat man,” said Sally coldly.

Fillmore refrained from discussing the point. He was sensitive.

“I’m going to do big things,” he substituted. “I’ve got a deal on at this very moment which— Well, I can’t tell you about it, but it’s going to be big. Well, what I’m driving at is about all this sort of thing”—he indicated the lighted front of Mrs. Meecher’s home-from-home with a wide gesture—“is that it’s over. Finished and done with. I’m in a position where all these people are entitled to call themselves my friends, simply because father put it in his will that I wasn’t to get the money till I was twenty-five, instead of letting me have it at twenty-one like anybody else. I wonder where I should have been by now if I could have got that money when I was twenty-one.”

“In the poorhouse, probably,” said Sally.

Fillmore was wounded. “Ah! you don’t believe in me,” he sighed.

“Oh, you would be all right if you had just one thing,” said Sally.

FILLMORE passed his qualities in swift review before his mental eye. Brains? Dash? Dignity? Initiative? All present and correct. He wondered where Sally imagined the hiatus to exist.

“One thing?” he said. “What’s that?”

“A nurse.”

Fillmore’s sense of injury deepened.

“I shall find my place in the world,” he said sulkily.

“Oh, you’ll find your place all right,” said Sally.

“Well, then—”

“And I’ll come and bring you jelly and read to you on the days when visitors are allowed— Oh, hullo.”

The last remark was addressed to a young man who had been swinging briskly along the sidewalk from the direction of Broadway and who now, coming abreast of them, stopped.

“Good evening, Mr. Foster.”

“Good evening, Mr. Foster.”

“Good evening, Miss Nicholas.”

“You don’t know my brother, do you?”

“I don’t believe I do.”

“He left the underworld before you came to it,” said Sally. “You wouldn’t think it to look at him, but he was once a prune eater, even as you and I. Mrs. Meecher looks on him as a son.”

The two men shook hands. Fillmore was not short, but Gerald Foster with his lean, well-built figure seemed to tower over him. He was an Englishman, a man in the middle twenties, clean-shaven, keen-eyed, and very good to look at. Fillmore, who had recently been going in for one those sum-up-your-fellow-man-at-a-glance courses, the better to fit himself for his career of greatness, was rather impressed. It seemed to him that this Mr. Foster, like himself, was one of those who Get There. If you are that kind yourself, you get into the knack of recognizing the others. It is a sort of gift.

There was a few moments’ desultory conversation, of the kind that usually follows an introduction, and then Fillmore, by no means sorry to get the chance, took advantage of the coming of this new arrival to remove himself.

Sally stood for a moment, watching him till he had disappeared round the corner. Then she dismissed him from her mind; and, turning to Gerald Foster, slipped her arm through his.

“Well, Jerry darling,” she said. “What a shame you couldn’t come to the party. Tell me all about everything. . . .”

IT was exactly two months since Sally had become engaged to Gerald Foster; but so rigorously had they kept their secret that nobody at Mrs. Meecher’s so much as suspected it. To Sally, who all her life had hated concealing things, secrecy of any kind was objectionable; but in this matter Gerald had shown an odd streak almost of furtiveness in his character. An announced engagement complicated life. People fussed about you and bothered you. People either watched you or avoided you. Such were his arguments, and Sally, who would have glossed over and found excuses for a disposition on his part toward homicide or arson, put them down to artistic sensitiveness. There is nobody so sensitive as your artist, particularly if he be unsuccessful; and when an artist has so little success that he cannot afford to make a home for the woman he loves, his sensitiveness presumably becomes great indeed. It seemed absurd to think of Gerald as an unsuccessful man. He was one of those men of whom one could predict that they would succeed very suddenly and rapidly—overnight, as it were.

“The party,” said Sally, “went off splendidly.” They had passed the boarding-house door and were walking slowly down the street. “Everybody enjoyed themselves, I think, though that lump Fillmore did his best to spoil things by coming looking like an advertisement of What the Smart Man Will Wear This Season. You didn’t see his waistcoat just now. He had covered it up. Conscience, I suppose. It was white and bulgy and gleaming and full of pearl buttons and everything. I saw Augustus Bartlett curl up like a burnt feather when he caught sight of it. Still, time seemed to heal the wound, and everybody relaxed after a bit. Mr. Faucitt made a speech, and I made a speech and cried, and—oh, it was all very festive. It only needed you.”

“I wish I could have come. I had to go to that dinner, though. Sally!” Gerald paused, and Sally saw that he was electric with suppressed excitement. “Sally, the play’s going to be put on!”

Sally gave a little gasp. She had lived this moment in anticipation for weeks. She had always known that sooner or later this would happen. She had read his plays over and over again, and was convinced that they were wonderful. Of course hers was a biased view; but then Elsa Doland also admired them, and Elsa’s opinion was one that carried weight. Elsa was another of those people who were bound to succeed suddenly. Even old Mr. Faucitt, who was a stern judge of acting and rather inclined to consider that nowadays there was no such thing, believed that she was a girl with a future.

“Jerry!” She gave his arm a hug. “How simply terrific! Then Goble and Kohn have changed their minds and want it after all? I knew they would.”

A SLIGHT cloud seemed to dim for a moment the sunniness of the author’s mood. “No, not that one,” he said reluctantly. “No hope there, I’m afraid. I saw Goble this morning about that, and he said it didn’t add up right. The one that’s going to be put on is ‘The Primrose Way.’ You remember? It’s got a big part for a girl in it.”

“Of course. The one Elsa liked so much. Well, that’s just as good. Who’s going to do it? I thought you hadn’t sent it out again.”

“Well, it happens. . . .” Gerald hesitated once more. “It seems that this man I was dining with to-night—a man named Cracknell . . .”

“Cracknell? Not the Cracknell?”

“The Cracknell?”

“The one people are always talking about. The man they call the Millionaire Kid.”

“Yes. Why, do you know him?”

“He was at college with Fillmore. I never saw him, but he must be rather a painful person.”

“Oh, he’s all right. Not much brains, of course, but—well, he’s all right. And, anyway, he wants to put the play on.”

“Well, that’s splendid,” said Sally, but she could not get the right ring of enthusiasm into her voice. She had had ideals for Gerald. She had dreamed of him invading Broadway triumphantly under the banner of one of the big managers whose name carried a prestige, and there seemed something unworthy in this association with a man whose chief claim to eminence lay in the fact that he was credited by metropolitan gossip with possessing the largest private stock in existence.

“I thought you would be pleased,” said Gerald.

“Oh, I am,” said Sally.

With the buoyant optimism which never deserted her for long, she had already begun to cast off her momentary depression. After all, did it matter who financed a play so long as it obtained a production? The real thing that mattered was the question of who was going to play the leading part, that deftly drawn character which had so excited the admiration of Elsa Doland.

“Who will play Ruth?” she asked. “You must have somebody wonderful. It needs a tremendously clever woman. Did Mr. Cracknell say anything about that?”

“Oh, yes, we discussed that, of course.”

“Well?”

“Well, it seems—” Again Sally noticed that odd, almost stealthy, embarrassment.

He broke off, was silent for a moment, and began again with a question: “Do you know Mabel Hobson?”

“Mabel Hobson? I’ve seen her in the Follies, of course.”

SALLY started. A suspicion had stung her, so monstrous that its absurdity became manifest the moment it had formed. And yet was it absurd? Most Broadway gossip filtered eventually into the boarding house. Sally was aware that the name of Reginald Cracknell, which was always getting itself linked with somebody, had been coupled with that of Miss Hobson. It seemed likely that in this instance rumor spoke truth, for the lady was of that compellingly blond beauty which attracts the Cracknells of this world. But even so . . .

“It seems that Cracknell—” said Gerald. “Apparently this man Cracknell—” He was finding Sally’s bright, horrified gaze somewhat trying. “Well, the fact is Cracknell believes in Mabel Hobson—and—well, he thinks this part would suit her.”

“Oh, Jerry!”

There was an uncomfortable silence. They turned and walked back in the direction of the boarding house. Somehow Gerald’s arm had managed to get itself detached from Sally’s. She was conscious of a curious dull ache that was almost like a physical pain. “Jerry! Is it worth it?” she burst out vehemently.

The question seemed to sting the young man into something like his usual decisive speech. “Worth it? Of course it’s worth it. It’s a Broadway production. That’s all that matters. Good heavens! I’ve been trying long enough to get a play on Broadway, and it isn’t likely that I’m going to chuck away my chance, when it comes along, just because one might do better in the way of casting.”

“But, Jerry! Mabel Hobson! It’s . . . it’s murder! Murder in the first degree.”

“Nonsense. She’ll be all right. The part will play itself. Besides, she has a personality and a following, and Cracknell will spend all the money in the world to make the thing a success. And it will be a start, whatever happens. Of course it’s worth it.”

Fillmore would have been impressed by this speech. He would have recognized and respected in it the unmistakable ring which characterizes even the lightest utterances of those who get there. On Sally it had not immediately that effect. Nevertheless, her habit of making the best of things, working together with that primary article of her creed that the man she loved could do no wrong, succeeded finally in raising her spirits.

“You old darling,” she said, affectionately attaching herself to the vacant arm once more and giving it a penitent squeeze, “you’re quite right. Of course you are. I can see it now. I was only a little startled at first. Everything’s going to be wonderful. Let’s get all our chickens out and count ’em. How are you going to spend the money?”

“I know how I’m going to spend a dollar of it,” said Gerald, completely restored.

“I mean the big money. What’s a dollar?”

“It pays for a marriage license.”

Sally gave his arm another squeeze. “Ladies and gentlemen,” she said. “Look at this man. Observe him. My partner!”

II

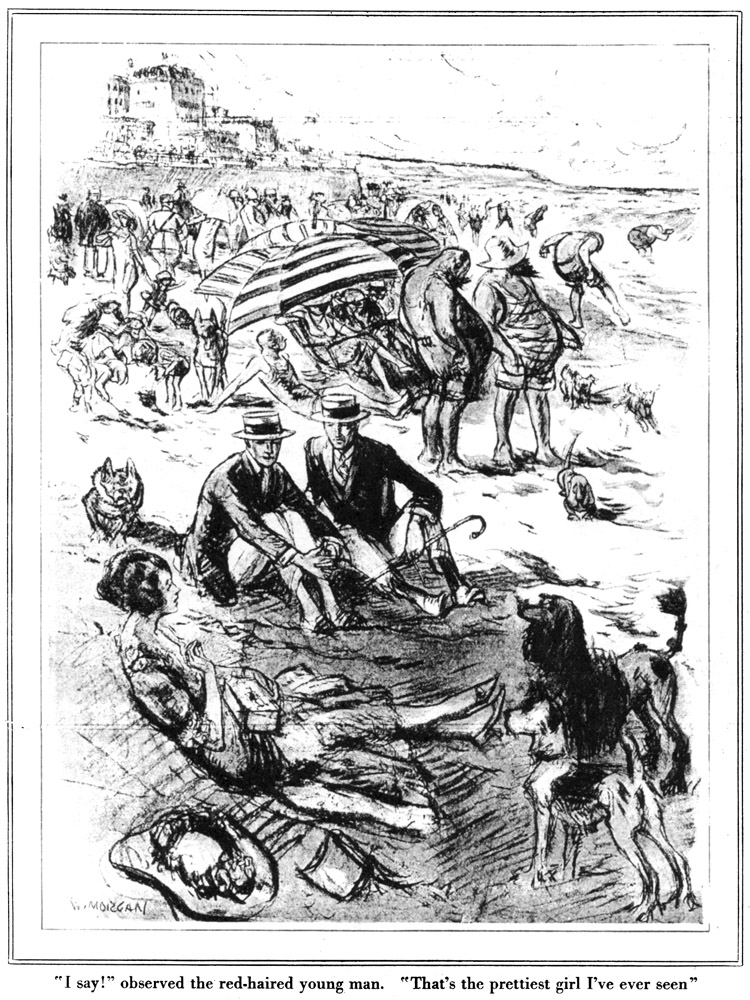

SALLY was sitting with her back against a hillock of golden sand, watching with half-closed eyes the denizens of Roville-sur-Mer at their familiar morning occupations. At Roville, as at most French seashore resorts, the morning is the time when the visiting population assembles in force on the beach. Whiskered fathers of families made cheerful patches of color in the foreground. Their female friends and relatives clustered in groups under gay parasols. Dogs roamed to and fro, and children dug industriously with spades, ever and anon suspending their labors in order to smite one another with these handy implements. One of the dogs, a poodle of military aspect, wandered up to Sally, and, discovering that she was in possession of a box of candy, decided to remain and await developments.

Few things are so pleasant as the anticipation of them, but Sally’s vacation had proved an exception to this rule. It had been a magic month of lazy happiness. She had drifted luxuriously from one French town to another till the charm of Roville, with its blue sky, its Casino, its snow-white hotels along the Promenade, and its general glitter and gayety, had brought her to a halt. Here she could have stayed indefinitely, but the voice of America was calling her back. Gerald had written to say that “The Primrose Way” was to be produced in Detroit preliminary to its New York run, so soon that, if she wished to see the opening, she must return at once. A scrappy, hurried, unsatisfactory letter, the letter of a busy man, but one that Sally could not ignore. She was leaving Roville to-morrow.

To-day, however, was to-day, and she sat and watched the bathers with a familiar feeling of peace, reveling as usual in the still novel sensation of having nothing to do.

But if there was one drawback she had discovered to a morning on the Roville plage, it was that you had a tendency to fall asleep, and this is a degrading thing to do so soon after breakfast, even if you are on a holiday. Usually Sally fought stoutly against the temptation, but to-day she had almost dozed off, when she was aroused by voices close at hand talking English, a novelty in Roville, and the sound of the familiar tongue jerked Sally back from the borders of sleep. A few feet away two men had seated themselves on the sand.

From the first moment she had set out on her travels it had been one of Sally’s principal amusements to examine the strangers whom chance threw in her way, and to try, by the light of her intuition, to fit them out with characters and occupations. Out of the corner of her eye she inspected these two men.

THE first of the pair did not attract her. He was a tall, dark man whose tight, precise mouth and rather high cheek bones gave him an appearance vaguely sinister. He had the dusky look of the clean-shaven man whose life is a perpetual struggle with a determined beard. He certainly shaved twice a day, and just as certainly had the self-control not to swear when he cut himself. She could picture him smiling nastily when this happened. “Hard,” diagnosed Sally. “I shouldn’t like him. A lawyer or something, I think.”

She turned to the other and found herself looking into his eyes. This was because he had been staring at Sally with the utmost intentness ever since his arrival. His mouth had opened slightly. He had the air of a man who, after many disappointments, has at last found something worth looking at. “Rather a dear,” decided Sally.

He was a sturdy, thick-set young man with an amiable, freckled face and the reddest hair Sally had ever seen. He had a square chin, and at one angle of the chin a slight cut. And Sally was convinced that, however he had behaved on receipt of that wound, it had not been with superior self-control. “A temper, I should think,” she meditated. “Very quick, but soon over. Not very clever, I should say, but nice.”

She looked away, finding his fascinated gaze a little embarrassing.

The dark man resumed the conversation which had presumably been interrupted by the process of sitting down.

“And how is Scrymgeour?” he inquired.

“Oh, all right,” replied the young man with red hair absently. Sally was looking straight in front of her, but she felt that his eyes were still busy.

“I was surprised at his being here. He told me he meant to stay in Paris.”

There was a slight pause. Sally gave the attentive poodle a piece of nougat.

“I say!” observed the red-haired young man in clear, penetrating tones that vibrated with intense feeling. “That’s the prettiest girl I’ve ever seen in my life!” . . .

At this frank revelation of the red-haired young man’s personal opinions Sally, though considerably startled, was not displeased. A broad-minded girl, the outburst seemed to her a legitimate comment on a matter of public interest. The young man’s companion, on the other hand, was unmixedly shocked.

“My dear fellow!” he ejaculated.

“Oh, it’s all right,” said the red-haired young man, unmoved. “She can’t understand. There isn’t a bally soul in this dashed place that can speak a word of English. If I didn’t happen to remember a few odd bits of my French, I should have starved by this time. That girl,” he went on, returning to the subject most imperatively occupying his mind, “is an absolute topper! I give you my solemn word, I’ve never seen anybody to touch her. Look at those hands and feet. You don’t get them outside France. Of course her mouth is a bit wide,” he said reluctantly.

SALLY’S immobility, added to the other’s assurance concerning the linguistic deficiencies of the inhabitants of Roville, seemed to reassure the dark man. He breathed again. He looked at Sally, who was now dividing her attention between the poodle and a raffish-looking mongrel that had joined the party, and returned to the topic of the mysterious Scrymgeour.

“How is Scrymgeour’s dyspepsia?”

The red-haired young man seemed but faintly interested in the vicissitudes of Scrymgeour’s interior.

“Do you notice the way her hair sort of curls over her ears?” he said. “Eh? Oh, pretty much the same, I think.”

“What hotel are you staying at?”

“The Normandie.”

Sally, dipping into the box for another chocolate cream, gave an imperceptible start. She, too, was staying at the Normandie. She presumed that her admirer was a recent arrival, for she had seen nothing of him at the hotel.

“The Normandie?” The dark man looked puzzled. “Where is it?”

“It’s a little shanty down near the station. Not much of a place. Still, it’s cheap, and the cooking’s all right.”

His companion’s bewilderment increased. “What on earth is a man like Scrymgeour doing there?” he said. “I should have thought he would have gone to the Splendide.” He mused on this problem in a dissatisfied sort of way for a moment, then seemed to reconcile himself to the fact that a rich man’s eccentricities must be humored. “I’d like to see him again. Ask him if he will dine with me at the Splendide to-night. Say eight sharp.”

Sally, occupied with her dogs, whose numbers had now been augmented by a white terrier with a black patch over his left eye, could not see the young man’s face; but his voice, when he replied, told her that something was wrong. There was a false airiness in it.

“Oh, Scrymgeour isn’t in Roville.”

“No? Where is he?”

“Paris, I believe.”

“What!” The dark man’s voice sharpened. He sounded as though he were cross-examining a reluctant witness. “Then why aren’t you there? What are you doing here? Did he give you a holiday?”

“Yes, he did!”

“When do you rejoin him?”

“I don’t!”

“What!”

The red-haired young man’s manner was now unmistakably dogged.

“Well, if you want to know,” he said, “the old blighter fired me the day before yesterday. . . .”

There was a shuffling of sand as the dark man sprang up. Sally, intent on the drama which was unfolding itself beside her, absent-mindedly gave the poodle a piece of candy which should by rights have gone to the terrier. She shot a swift glance sideways, and saw the dark man standing in an attitude rather reminiscent of the stern father of melodrama about to drive his erring daughter out into the snow. The red-haired young man, outwardly stolid, was gazing before him down the beach at a fat bather in an orange suit.

“Do you mean to tell me,” demanded the dark man, “that after all the trouble the Family took to get you what was practically a sinecure with endless possibilities if you only behaved yourself you have deliberately thrown away—” A despairing gesture completed the sentence. “Good God! You’re hopeless!”

The red-haired young man made no reply. He continued to gaze down the beach. Of all outdoor sports, few are more stimulating than watching middle-aged Frenchmen bathe. Drama, action, suspense—all are here. From the first stealthy testing of the water with an apprehensive toe to the final seal-like plunge, there is never a dull moment. Yet the young man with red hair, recently in the employment of Mr. Scrymgeour, eyed his free circus without any enjoyment whatever.

“It’s maddening! What are you going to do? What do you expect us to do? Are we to spend our whole lives getting you positions which you won’t keep? I can tell you we’re . . . it’s monstrous! It’s sickening!”

And with these words the dark man, apparently feeling, as Sally had sometimes felt in the society of her brother, the futility of mere language, turned sharply and stalked away up the beach.

He left behind him the sort of electric calm which follows the falling of a thunderbolt; that stunned calm through which the air seems still to quiver protestingly. How long this would have lasted one cannot say, for toward the end of the first minute it was shattered by a purely terrestrial uproar. With an abruptness heralded only by one short, low, gurgling snarl there sprang into being the prettiest dog fight that Roville had seen that season.

IT was the terrier with the black patch that began it. The fault was really Sally’s. Absorbed in the scene which had just concluded, and acutely inquisitive as to why the shadowy Scrymgeour had seen fit to dispense with the red-haired young man’s services, she had thrice in succession helped the poodle out of his turn. The third occasion was too much for the terrier.

It was a furious mêlée, which would have excited favorable comment even among the blasé residents of a negro quarter or the not easily pleased critics of a Lancashire mining village. From all over the beach dogs of every size, breed, and color were racing to the scene; and while some of these merely remained in the ringside seats and barked, a considerable proportion immediately started fighting one another on general principles, well content to be in action without bothering about first causes. The terrier had got the poodle by the left hind leg and was restating his war aims. The raffish mongrel was apparently endeavoring to fletcherize a complete stranger of the Sealyham family.

Sally was frankly unequal to the situation, as were the entire crowd of spectators who had come galloping up from the water’s edge. She had been paralyzed from the start. Snarling bundles bumped against her legs and bounced away again, but she made no move. Advice in fluent French rent the air. Arms waved, and well-filled bathing suits leaped up and down. But nobody did anything practical until in the center of the theatre of war suddenly appeared the red-haired young man.

THE only reason why dog fights do not go on forever is that Providence has decided that on such occasions there shall always be among those present one Master Mind; one wizard who, whatever his shortcomings in the other battles of life, is in this single particular sphere competent and dominating. At Roville-sur-Mer it was the red-haired young man. There was a magic in his soothing hands, a spell in his voice; and in a shorter time than one would have believed possible dog after dog had been sorted out and calmed down; until presently all that was left of Armageddon was one solitary small Scotch terrier, thoughtfully licking a chewed leg.

Having achieved this miracle, the young man turned to Sally. Gallant, one might say reckless, as he had been a moment before, he now gave indications of a rather pleasing shyness. He braced himself with that painful air of effort which announces to the world that an Englishman is about to speak a language other than his own.

“J’espère,” he said, having swallowed once or twice to brace himself up for the journey through the jungle of a foreign tongue. “J’espère que vous n’êtes pas—oh, dammit, what’s the word?—j’espère que vous n’êtes pas blessée?”

“Blessée?”

“Yes, blessée. Wounded. Hurt, don’t you know. Bitten. Oh, dash it. J’espère—”

“Oh, bitten!” said Sally, dimpling. “Oh, no, thanks very much. I wasn’t bitten. And I think it was awfully brave of you to save all our lives.”

The compliment seemed to pass over the young man’s head. He stared at Sally with horrified eyes. Over his amiable face there swept a vivid blush. His jaw dropped. “Oh, my sainted aunt!” he ejaculated.

Then, as if the situation was too much for him and flight the only possible solution, he spun round and disappeared at a walk so rapid that it was almost a run. Sally watched him go and was sorry that he had torn himself away. She still wanted to know why Scrymgeour had fired him.

Editor’s notes:

“an advertisement of What the Smart Man Will Wear This Season”: What better image to have in mind, “white and bulgy and gleaming and full of pearl buttons and everything,” than this J. C. Leyendecker advertisement for Arrow Collars?

fletcherize: to chew repeatedly and thoroughly, as advocated by Horace Fletcher (1849–1919), American food reformer

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums