Liberty, November 13, 1926

Part Nine

“YES, but why has George gone to the station?” asked Madame Eulalie.

Hamilton Beamish hesitated. Then, revolted by the thought that he should be hiding anything from this girl, he spoke:

“Can you keep a secret?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never tried.”

“Well, this is something quite between ourselves. Poor George is in trouble.”

“Any worse trouble than most bridegrooms?”

“I wish you would not speak like that,” said Hamilton Beamish, pained. “You seem to mock at Love.”

“Oh, I’ve nothing against love.”

“Love is the only thing worth while in the world. In peace Love tunes the shepherd’s reed, in war he mounts the warrior’s steed.”

“Yes, doesn’t he? You were going to tell me what George is in trouble about.”

Hamilton Beamish lowered his voice:

“Well, the fact is, on the eve of his wedding an old acquaintance of his has suddenly appeared.”

“Female?”

“Female.”

“I begin to see.”

“George wrote her letters. She still has them.”

“Worse and worse.”

“And if she makes trouble it will stop the wedding. Mrs. Waddington is only waiting for an excuse to forbid it. Already she has stated in so many words that she is suspicious of George’s morals.”

“How absurd! George is like the driven snow.”

“Exactly. A thoroughly fine-minded man. Why, I remember him once leaving the table at a bachelor dinner, because someone told an improper story.”

“HOW splendid of him! What was the story?”

“I don’t remember. Still, Mrs. Waddington has this opinion of him, so there it is.”

“All this sounds very interesting. What are you going to do about it?”

“Well, George has gone to the station to try to intercept this Miss Stubbs, and reason with her.”

“Miss Stubbs?”

“That is her name. By the way, she comes from your home town—East Gilead. Perhaps you know her?”

“I seem to recollect the name. So George has gone to reason with her?”

“Yes. But, of course, she will insist on coming here.”

“That’s bad.”

Hamilton Beamish smiled.

“Not quite so bad as you think,” he said. “You see, I have been giving the matter some little thought, and I may say I have the situation well in hand. I have arranged everything.”

“You have?”

“Everything.”

“You must be terribly clever.”

“Oh, well!” said Hamilton Beamish modestly.

“But, of course, I knew you were, the moment I read your Booklets. Have you a cigarette?”

“I beg your pardon.”

Madame Eulalie selected a cigarette from his case and lighted it. Hamilton Beamish, taking the match from her fingers, blew it out and placed it reverently in his left top waistcoat pocket.

“Go on,” said Madame Eulalie.

“Ah, yes,” said Hamilton Beamish, coming out of his thoughts. “We were speaking about George. It appears that George, before he left East Gilead, had what he calls an understanding, but which seems to me to have differed in no respect from an engagement, with a girl named May Stubbs. Unpleasant name!”

“Horrible. Just the sort of name I would want to change.”

“He then came into money, left for New York, and forgot all about her.”

“But she didn’t forget all about him?”

“Apparently not. I picture her as a poor, dowdy little thing—you know what these village girls are—without any likelihood of getting another husband. So she has clung to her one chance. I suppose she thinks that by coming here at this time she will force George to marry her.”

“But you are going to be too clever to let anything like that happen?”

“Precisely.”

“Aren’t you wonderful!”

“It is kind of you to say so,” said Hamilton Beamish, pulling down his waistcoat.

“What have you arranged?”

“Well, the whole difficulty is that at present George is in the position of having broken the engagement. So, when this May Stubbs arrives, I am going to get her to throw him over of her own free will.”

“And how do you propose to do that?”

“Quite simply. You see, we may take it that she is a prude. I have, therefore, constructed a little drama by means of which George will appear an abandoned libertine.”

“George!”

“She will be shocked and revolted and will at once break off all relations with him.”

“I see. Did you think all this out by yourself?”

“Entirely by myself.”

“You’re too clever for one man. You ought to incorporate.”

It seemed to Hamilton Beamish that the moment had arrived to speak out frankly and without subterfuge; to reveal in the neatest phrases at his disposal the love that had been swelling his heart like some yeasty ferment ever since he had taken a speck of dust out of this girl’s eye on the doorstep of Number 16 East Seventy-ninth Street. And he was about to begin doing so when she looked past him and uttered a pleased laugh:

“Why, George Finch!”

Hamilton Beamish turned, justly exasperated. Every time he endeavored to speak his love, it seemed that something had to happen to prevent him. Yesterday it had been the loathsome Charley on the telephone, and now it was George Finch.

George was standing in the doorway, flushed, as if he had been walking fast. He was staring at the girl in a manner that Beamish resented. To express his resentment he coughed sharply.

George paid no attention. He continued to stare.

“And how is Georgie? You have interrupted a most interesting story, George.”

“May!” George placed a finger inside his collar, as if trying to loosen it. “May! I—I’ve just been down to the station to meet you.”

“I came by car.”

“May?” exclaimed Hamilton Beamish, a horrid light breaking upon him.

Madame Eulalie turned to him brightly.

“Yes; I’m the dowdy little thing.”

“But you’re not a dowdy little thing,” said Hamilton Beamish, finding thought difficult, but concentrating on the one incontrovertible fact.

“I was when George knew me.”

“And your name is Madame Eulalie.”

“My professional name. Didn’t we agree that anyone who had a name like May Stubbs would want to change it as quickly as possible?”

“You are really May Stubbs?”

“I am.”

HAMILTON BEAMISH bit his lip. He regarded his friend coldly.

“I congratulate you, George. You are engaged to two of the prettiest girls I have ever seen.”

“How very charming of you, Jimmy!” said Madame Eulalie.

George Finch’s face worked convulsively.

“But, May, honestly—have a heart! You don’t really look on me as engaged to you?”

“Why not?”

“But—but—I thought you had forgotten all about me.”

“What, after all those beautiful letters you wrote?”

“Boy and girl affair,” babbled George.

“Was it, indeed!”

“But, May!——”

Hamilton Beamish had been listening to these exchanges with a rapidly rising temperature. His heart was pounding feverishly in his bosom. There is no one who becomes so primitive, when gripped by love, as the man who all his life has dwelt in the cool empyrean of the intellect. For twenty years and more Hamilton Beamish had supposed that he was above the crude passions of the ordinary man, and when love got him it got him good. And now, standing there and listening to these two, he was conscious of a jealousy so keen that he could no longer keep silent.

Hamilton Beamish the thinker had ceased to be, and there stood in his place Hamilton Beamish the descendant of ancestors who had conducted their love affairs with stout clubs, and who, on seeing a rival, wasted no time in calm reflection, but jumped on him like a ton of bricks and did their best to bite his head off.

If you had given him a bearskin and taken away his spectacles, Hamilton Beamish at this moment would have been Prehistoric Man.

“Hey!” said Hamilton Beamish.

“But, May, you know you don’t love me.”

“Hey!” said Hamilton Beamish again, in a nasty, snarling voice. And silence fell.

The cave man adjusted his spectacles and glared at his erstwhile friend with venomous dislike. His fingers twitched as if searching for a club.

“Listen to me, you!” said Hamilton Beamish. “And get me right! See? That’ll be about all from you about this girl loving you, unless you want me to step across and bust you on the beezer. I love her, see? And she’s going to marry me, see? And nobody else, see? And anyone who says different had better notify his friends where he wants the body sent, see? Love you, indeed? A swell chance! I’m the little guy she’s going to marry, see? Me!”

And, folding his arms, the thinker paused for a reply.

It did not come immediately. George Finch, unused to primitive emotions from this particular quarter, remained dumb. It was left for Madame Eulalie to supply comment.

“Jimmy!” she said faintly.

HAMILTON BEAMISH caught her masterfully around the waist. He kissed her eleven times.

“So that’s that!” said Hamilton Beamish.

“Yes, Jimmy.”

“We’ll get married tomorrow.”

“Yes, Jimmy.”

“You are my mate!”

“Yes, Jimmy.”

“All right, then,” said Hamilton Beamish.

George came to life like a clockwork toy.

“Hamilton, I congratulate you!”

“Thanks, thanks.”

Mr. Beamish spoke a little dazedly. He blinked. Already the ferment had begun to subside, and Beamish the cave man was fast giving place to Beamish of the Booklets. He was dimly conscious of having expressed himself a little too warmly and in language that in a calmer moment he would never have selected. Then he caught the girl’s eyes fixed on him adoringly, and he had no regrets.

“Thanks,” he said again.

“May is a splendid girl,” said George. “You will be very happy. I speak as one who knows her. How sympathetic you always were in the old days, May.”

“Was I?”

“You certainly were. Don’t you remember how I used to bring my troubles to you, and we would sit together on the sofa in front of your parlor fire?”

“We were always afraid someone was listening at the door.”

“If they had been, the only thing they’d have found out would have been the lamp.”

“Hey!” said Hamilton Beamish abruptly.

“Those were happy days,” said Madame Eulalie.

“And do you remember how your little brother used to call me April Showers?”

“He did, did he?” said Mr. Beamish, snorting a little. “Why?”

“Because I brought May flowers.”

“That’s quite enough,” said Hamilton Beamish, not without reason. “I should like to remind you, Finch, that this lady is engaged to me.”

“Oh, quite,” said George.

“Endeavor not to forget it,” said Hamilton Beamish curtly. “And later on, should you ever come to share a meal at our little home, be sparing of your reminiscences of the dear old days. You get—you take my meaning?”

“Oh, quite.”

“Then we will be getting along. May has to return to New York immediately, and I am going with her. You must look elsewhere for a best man at your wedding. You are very lucky to be having a wedding at all. Good-by, George. Come, darling.”

The two-seater was moving down the drive, when Hamilton Beamish clapped a hand to his forehead.

“I had quite forgotten!” he exclaimed.

“What have you forgotten, Jimmy dear?”

“Just something I wanted to say to George, sweetheart. Wait here for me.”

“George,” said Hamilton Beamish, returning to the hall, “I have just remembered something. Ring for Ferris and tell him to stay in the room with the wedding presents and not leave it for a moment. They aren’t safe, lying loose like that. You should have had a detective.”

“We intended to; but Mr. Waddington insisted on it so strongly that Mrs. Waddington said the idea was absurd. I’ll go and tell Ferris immediately.”

“Do so,” said Hamilton Beamish.

He passed out on to the lawn and, reaching the rhododendron bushes, whistled softly.

“Now what?” said Fanny, pushing out an inquiring head.

“Oh, there you are.”

“Yes, here I am. When does the show start?”

“It doesn’t,” said Hamilton Beamish. “Events have occurred which render our little ruse unnecessary. So you can return to your home and husband as soon as you please.”

“Oh?” said Fanny.

She plucked a rhododendron leaf and crushed it reflectively.

“I don’t know as I’m in any hurry,” she said. “I kind of like it out here—the air and the sun and the birds and everything. I guess I’ll stick around for a while.”

Hamilton Beamish regarded her with a quiet smile.

“Certainly, if you wish it,” he said. “I should mention, however, that if you were contemplating another attempt on those jewels, you would do well to abandon the idea. From now on a large butler will be stationed in the room, watching over it, and there might be unpleasantness.”

“Oh?” said Fanny meditatively.

“Yes.”

“You think of everything, don’t you?”

“I thank you for the compliment,” said Hamilton Beamish.

* * *

GEORGE did not delay. Always sound, Hamilton Beamish’s advice appeared to him now even sounder than usual. He rang the bell for Ferris.

“Oh, Ferris,” said George. “Mr. Beamish thinks you had better stay in the room with the wedding presents and keep an eye on them.”

“Very good, sir.”

“In case somebody tries to steal them, you know.”

“Just so, sir.”

Relief, as it always does, had given George a craving for conversation. He wanted to buttonhole some fellow creature and babble. He would have preferred this fellow creature to have been anyone but Ferris, for he had not forgotten the early passages of their acquaintanceship, and seemed still to sense in the butler’s manner a lingering antipathy. But Ferris was there, so he babbled to him.

“Nice day, Ferris.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Nice weather.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Nice country round here.”

“No, sir.”

George was somewhat taken aback.

“Did you say ‘no, sir’?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Oh, ‘yes, sir’? I thought you said ‘no, sir.’ ”

“Yes, sir. No, sir.”

“You mean you don’t like the country round here?”

“No, sir.”

“Why not?”

“I disapprove of it, sir.”

“Why?”

“It is not the sort of country to which I have been accustomed, sir. It is not like the country round Little-Seeping-in-the-Wold.”

“Where’s that?”

“In England, sir.”

“I suppose the English country’s nice?”

“I believe it gives uniform satisfaction, sir.”

GEORGE felt damped. In his mood of relief he had hoped that Ferris might have brought himself to sink the butler in the friend.

“What don’t you like about the country round here?”

“I disapprove of the mosquitoes, sir.”

“But there are only a few.”

“I disapprove of even one mosquito, sir.”

George tried again:

“I suppose everybody downstairs is very excited about the wedding, Ferris?”

“By ‘everybody downstairs’ you allude to——?”

“The—er—the domestic staff.”

“I have not canvassed their opinions, sir. I mix very little with my colleagues.”

“I suppose you disapprove of them?” said George, nettled.

“Yes, sir.”

“Why?”

The butler raised his eyebrows. He preferred the lower middle classes not to be inquisitive. However, he stooped to explain.

“Many of them are Swedes, sir, and the rest are Irish.”

“You disapprove of Swedes?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why?”

“Their heads are too square, sir.”

“And you disapprove of the Irish?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why?”

“Because they are Irish, sir.”

George shifted his feet uncomfortably.

“I hope you don’t disapprove of weddings, Ferris?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why?”

“They seem to me melancholy occasions, sir.”

“Are you married, Ferris?”

“A widower, sir.”

“Well, weren’t you happy when you got married?”

“No, sir.”

“Was Mrs. Ferris?”

“She appeared to take a certain girlish pleasure in the ceremony, sir, but it soon flickered out.”

“How do you account for that?”

“I could not say, sir.”

“I’m sorry weddings depress you, Ferris. Surely when two people love each other and mean to go on loving each other——”

“Marriage is not a process for prolonging the life of love, sir. It merely mummifies its corpse.”

“But, Ferris, if there were no marriages, what would become of posterity?”

“I see no necessity for posterity, sir.”

“You disapprove of it?”

“Yes, sir.”

George walked pensively out on to the drive in front of the house. He was conscious of a diminution of the exuberant happiness that had led him to engage the butler in conversation.

He saw clearly now that, Ferris’s conversation being what it was, a bridegroom who engaged him in it on his wedding-day was making a blunder.

He looked out upon the pleasant garden with sobered gaze: and, looking, was aware of Sigsbee H. Waddington approaching. Sigsbee’s manner was agitated. He conveyed the impression of having heard bad news or of having made some discovery that disconcerted him.

“Say, listen!” said Sigsbee H. “What’s that infernal butler doing in the room with the wedding presents?”

“Keeping guard over them.”

“Who told him to?”

“I did.”

“Hell’s bells!” said Sigsbee H.

He gave George a peculiar look and shimmered off. If George had been more in the frame of mind to analyze the looks of his future father-in-law, he might have seen in this one a sort of shuddering loathing. But he was not in the frame of mind. Besides, Sigsbee H. Waddington was not the kind of man whose looks one analyzed. He was one of those negligible men whom one pushes out of sight and forgets about. George proceeded to forget about him almost immediately.

He was still forgetting about him when an automobile appeared round the bend of the drive and, stopping beside him, discharged Mrs. Waddington, Molly, and a man with a face like a horse, whom, from his clerical costume, George took correctly to be the deputy from Flushing.

“Molly!” cried George.

“Here we are, angel,” said Molly.

“And mother!” said George, with less heartiness.

“Mother!” said Mrs. Waddington, with still less heartiness than George.

“This is the Rev. Gideon Voules,” said Molly. “He’s going to marry us.”

“This,” said Mrs. Waddington, turning to the clergyman and speaking in a voice which seemed to George’s ear to contain too strong a note of apology, “is the bridegroom.”

THE Rev. Gideon Voules looked at George with a dull and poached-egg-like eye. He did not seem to the latter to be a frightfully cheery sort of person; but, after all, when you’re married you’re married, no matter how like a poached egg the presiding minister may look.

“How do you do?” said the Rev. Gideon.

“I’m fine,” said George. “How are you?”

“I am in robust health, I thank you.”

“Splendid! Nothing wrong with the ankles, eh?”

The Rev. Gideon glanced down at them and seemed satisfied with this section of his lower limbs, even though they were draped in white socks.

“Nothing, thank you.”

“So many clergymen nowadays,” explained George, “are falling off chairs and spraining them.”

“I never fall off chairs.”

“Then you’re just the fellow I’ve been scouring the country for,” said George. “If all clergymen were like you——”

Mrs. Waddington came to life.

“Would you care for a glass of milk?”

“No, thank you, mother,” said George.

“I was not addressing you,” said Mrs. Waddington. “I was speaking to Mr. Voules. He has had a long drive and no doubt requires refreshment.”

“Of course, of course,” said George. “What am I thinking about? Yes, you must certainly stoke up and preserve your strength. We don’t want you fainting halfway through the ceremony.”

“He would have every excuse,” said Mrs. Waddington.

She led the way into the dining-room, where light refreshments were laid out on a side table—a side table brightly decorated by the presence of Sigsbee H. Waddington, who was sipping a small gin and ginger ale and watching with lowering gaze the massive imperturbability of Ferris the butler. Ferris, though he obviously disapproved of wedding presents, was keeping a loyal eye on them.

“What are you doing here, Ferris?” asked Mrs. Waddington.

The butler raised the loyal eye.

“Guarding the gifts, madam.”

“Who told you to?”

“Mr. Finch, madam.”

Mrs. Waddington shot a look of disgust at George.

“There is no necessity whatever.”

“Very good, madam.”

“Only an imbecile would have suggested such a thing.”

“Precisely, madam.”

The butler retired. Sigsbee Horatio, watching him go, sighed unhappily. What was the good of him going now? felt Sigsbee. From now on the room would be full. Already automobiles were beginning to arrive, and a swarm of wedding guests had begun to settle upon the refreshments on the side table.

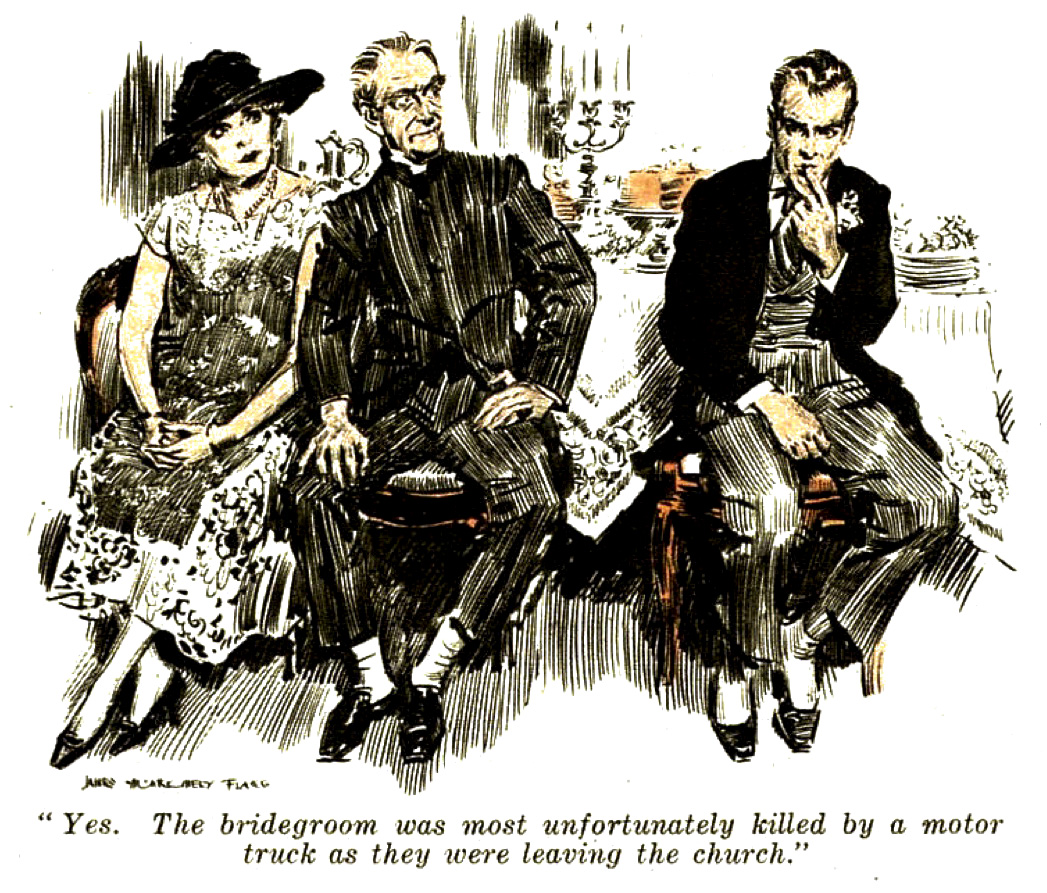

The Rev. Gideon Voules, thoughtfully lowering a milk and ham sandwich into the abyss, had drawn George into a corner and was endeavoring to make his better acquaintance.

“I always like to have a little chat with the bridegroom before the ceremony,” he said. “It is agreeable to be able to feel that he is, in a sense, a personal friend.”

“Very nice of you,” said George, touched.

“I married a young fellow in Flushing named Miglett the other day—Claude R. Miglett. Perhaps you recall the name?”

“No.”

“AH? I thought you might have seen it in the papers. They were full of the affair. I always feel that, if I had not made a point of establishing personal relations with him before the ceremony, I should not have been in a position to comfort his bride as I did after the accident.”

“Accident?”

“Yes. The bridegroom was most unfortunately killed by a motor truck as they were leaving the church.”

“Good heavens!”

George tottered away. Once more there was creeping over him that gray foreboding which had come to him earlier in the day. So reduced was his nervous system that he actually sought comfort in the society of Sigsbee Horatio. After all, he thought, whatever Sigsbee’s shortcomings as a man, he at least was a friend. A philosopher with the future of the race at heart might sigh as he looked upon Sigsbee H. Waddington, but in a bleak world George could not pick and choose his chums.

A moment later there was forced upon him the unpleasing discovery that in supposing Mr. Waddington liked him he had been altogether too optimistic. The look that his future father-in-law bestowed upon him as he sidled up was not one of affection. It was the sort of look which, had he been sheriff of Gory Gulch, Arizona, the elder man might have bestowed upon a horse-thief.

“Darned officious!” rumbled Sigsbee H. in a querulous undertone. “Officious and meddling.”

“Eh?” said George.

“Telling that butler to come in here and watch the presents.”

“But, good heavens, don’t you realize that if I hadn’t told him, someone might have sneaked in and stolen something?”

Mr. Waddington’s expression was now that of a cowboy who, leaping into bed, discovers too late that a frolicsome friend has placed a cactus between the sheets; and George, at the lowest ebb, was about to pass on to the refreshment table, to see whether a little potato salad might not act as a restorative, when there stepped from the crowd gathered round the food a large and ornately dressed person chewing the remnant of a slab of caviar on toast.

George had a dim recollection of having seen him among the guests at that first dinner party at Number 16 East Seventy-ninth Street. His memory had not erred: the newcomer was no less a man than United Beef.

“HELLO there, Waddington,” said United Beef.

“Ur,” said Sigsbee Horatio. He did not like the other, who had once refused to lend him money and—what was more—had gone to the mean length of quoting Shakespeare to support his refusal.

“Say, Waddington,” proceeded United Beef, “don’t I seem to remember you coming to me some time ago and asking about that motion picture company, the Finer and Better? You were thinking of putting some money in, if I recollect.”

An expression of acute alarm at once shot into Mr. Waddington’s face. He gulped painfully.

“Not me,” he said hastily. “Not me. Get it out of your nut that it was I who wanted to buy the stuff. I just thought that if the stock was any good my dear wife might be interested.”

“Same thing.”

“It is not at all the same thing.”

“Do you happen to know if your wife bought any?”

“No, she didn’t. I heard later that the company was no good, so I did not mention it to her.”

“Too bad,” said United Beef. “Too bad.”

“What do you mean, too bad?”

“Well, a rather remarkable thing has happened. Quite a romance, in its way. As a motion picture company the thing was, as you say, no good. But yesterday, when a workman started to dig a hole on the lot to put up a ‘For Sale’ sign, I’m darned if he didn’t strike oil.”

Don’t miss the breath-taking, dramatic climaxes of Molly’s wedding-day. Does Mrs. Waddington’s presentiment come true? Will George Finch’s youth in the wide open spaces of the West rise up like a specter to confront him? Or will youth and true love triumph over all obstacles? Read next week’s installment.

Note:

This is the only version in which the Reverend Gideon Voules says that the bridegroom, Claude R. Miglett, was the one killed by a truck as they were leaving the church, and says that Voules was in a position to comfort his bride after the accident. The UK magazine and both US and UK books agree that it was the bride who was killed and that Voules comforted Miglett. The other three versions also have the minister’s stories about other fatalities, omitted in Liberty.

Printer’s error corrected above:

Magazine omitted first hyphen in “Little-Seeping-in-the-Wold”; supplied for consistency with Part 2 and with other sources.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums