The Saturday Evening Post, July 31, 1915

VIII—(Continued)

GEORGE EMERSON sat in his bedroom smoking a cigarette. A light of resolution was in his eyes. He glanced at the table beside his bed and at what was on that table, and the light of resolution flamed into a glare of fanatic determination. So might a medieval knight have looked on the eve of setting forth to rescue a maiden from a dragon.

His cigarette burned down. He looked at his watch, put it back, and lit another cigarette. His aspect was the aspect of one waiting for the appointed hour. Smoking his second cigarette, he resumed his meditations. They had to do with Aline Peters.

George Emerson was troubled about Aline Peters. Watching over her, as he did, with a lover’s eye, he had perceived that about her which distressed him. On the terrace that morning she had been abrupt to him—what in a girl of less angelic disposition one might have called snappy. Yes, to be just, she had snapped at him. That meant something. It meant that Aline was not well. It meant what her pallor and tired eyes meant—that the life she was leading was doing her no good.

Twelve nights had George dined at Blandings Castle, and on each of the twelve nights he had been distressed to see the manner in which Aline, declining the baked meats, had restricted herself to the miserable vegetable messes which were all that the doctor’s orders permitted to her suffering father. George’s pity had its limits. His heart did not bleed for Mr. Peters. Mr. Peters’ diet was his own affair. But that Aline should starve herself in this fashion, purely by way of moral support for her parent, was another matter.

George was perhaps a shade material. Himself a robust young man and taking what might be called an outsize in meals, maybe he attached too much importance to food as an adjunct to the perfect life. In his survey of Aline he took a line through his own requirements; and believing that twelve such dinners as he had seen Aline partake of would have killed him he decided that his loved one was on the point of starvation.

No human being, he held, could exist on such Barmecide feasts. That Mr. Peters continued to do so did not occur to him as a flaw in his reasoning. He looked on Mr. Peters as a sort of machine. Successful business men often give that impression to the young. If George had been told that Mr. Peters went along on gasoline, like an automobile, he would not have been much surprised. But that Aline—his Aline—should have to deny herself the exercise of that mastication of rich meats which, together with the gift of speech, raises man above the beasts of the field—— That was what tortured George.

He had devoted the day to thinking out a solution of the problem. Such was the overflowing goodness of Aline’s heart that not even he could persuade her to withdraw her moral support from her father and devote herself to keeping up her strength as she should do. It was necessary to think of some other plan.

And then a speech of hers had come back to him. She had said—poor child:

“I do get a little hungry sometimes—late at night generally.”

The problem was solved. Food should be brought to her late at night.

On the table by his bed was a stout sheet of packing paper. On this lay, like one of those pictures of still life that one sees on suburban parlor walls, a tongue, some bread, a knife, a fork, salt, a corkscrew and a small bottle of white wine.

It is a pleasure, when one has been able hitherto to portray George’s devotion only through the medium of his speeches, to produce these comestibles as Exhibit A, to show that he loved Aline with no common love; for it had not been an easy task to get them there. In a house of smaller dimensions he would have raided the larder without shame, but at Blandings Castle there was no saying where the larder might be. All he knew was that it lay somewhere beyond that green-baize door opening on the hall, past which he was wont to go on his way to bed. To prowl through the maze of the servants’ quarters in search of it was impossible. The only thing to be done was to go to Market Blandings and buy the things.

Fortune had helped him at the start by arranging that the Honorable Freddie, also, should be going to Market Blandings in the little runabout, which seated two. He had acquiesced in George’s suggestion that he, George, should occupy the other seat, but with a certain lack of enthusiasm, it seemed to George. He had not volunteered any reason as to why he was going to Market Blandings in the little runabout, and on arrival there had betrayed an unmistakable desire to get rid of George at the earliest opportunity.

As this had suited George to perfection, he being desirous of getting rid of the Honorable Freddie at the earliest opportunity, he had not been inquisitive, and they had parted on the outskirts of the town without mutual confidences.

George had then proceeded to the grocer’s, and after that to another of the Market Blandings inns—not the Emsworth Arms—where he had bought the white wine. He did not believe in white wine, for he was a young man with a palate and mistrusted country cellars; but he assumed that, whatever its quality, it would cheer Aline in the small hours.

He had then tramped the whole five miles back to the castle with his purchases. It was here that his real troubles began and the quality of his love was tested. The walk, to a heavily laden man, was bad enough; but it was as nothing compared with the ordeal of smuggling the cargo up to his bedroom. Superman though he was, George was alive to the delicacy of the situation. One cannot convey food and drink to one’s room in a strange house without, if detected, seeming to cast a slur on the table of the host. It was as one who carries dispatches through an enemy’s lines that George took cover, emerged from cover, dodged, ducked and ran; and the moment when he sank down on his bed, the door locked behind him, was one of the happiest of his life.

The recollection of that ordeal made the one he proposed to embark on now seem slight in comparison. All he had to do was to go to Aline’s room, knock softly on the door until signs of wakefulness made themselves heard from within, and then dart away into the shadows whence he had come, and so back to bed. He gave Aline credit for the intelligence that would enable her, on finding a tongue, some bread, a knife, a fork, salt, a corkscrew and a bottle of white wine on the mat, to know what to do with them—and perhaps to guess whose was the loving hand that had laid them there.

The second clause, however, was not important, for he proposed to tell her whose was the hand next morning. Other people might hide their light under a bushel—not George Emerson.

It only remained now to allow time to pass until the hour should be sufficiently advanced to insure safety for the expedition. He looked at his watch again. It was nearly two. By this time the house must be asleep.

He gathered up the tongue, the bread, the knife, the fork, the salt, the corkscrew and the bottle of white wine, and left the room. All was still. He stole downstairs.

On his chair in the gallery that ran round the hall, swathed in an overcoat and wearing rubber-soled shoes, the Efficient Baxter sat and gazed into the darkness. He had lost the first fine careless rapture, as it were, which had helped him to endure these vigils, and a great weariness was on him. He found difficulty in keeping his eyes open, and when they were open the darkness seemed to press on them painfully. In short, the Efficient Baxter had had about enough of it.

Time stood still. Baxter’s thoughts began to wander. He knew that this was fatal and exerted himself to drag them back. He tried to concentrate his mind on some one definite thing. He selected the scarab as a suitable object, but it played him false. He had hardly concentrated on the scarab before his mind was straying off to ancient Egypt, to Mr. Peters’ dyspepsia, and on a dozen other branch lines of thought.

He blamed the fat man at the inn for this. If the fat man had not thrust his presence and conversation on him he would have been able to enjoy a sound sleep in the afternoon, and would have come fresh to his nocturnal task. He began to muse on the fat man. And by a curious coincidence whom should he meet a few moments later but this same man.

It happened in a somewhat singular manner, though it all seemed perfectly logical and consecutive to Baxter. He was climbing up the outer wall of Westminster Abbey in his pyjamas and a tall hat, when the fat man, suddenly thrusting his head out of a window which Baxter had not noticed until that moment, said, “Hello, Freddie!” in a loud voice.

Baxter was about to explain that his name was not Freddie when he found himself walking down Piccadilly with Ashe Marson. Ashe said to him: “Nobody loves me. Everybody steals my grapefruit!” And the pathos of it cut the Efficient Baxter like a knife. He was on the point of replying when Ashe vanished, and Baxter discovered that he was not in Piccadilly, as he had supposed, but in an aëroplane with Mr. Peters, hovering over the castle.

Mr. Peters had a bomb in his hand, which he was fondling with loving care. He explained to Baxter that he had stolen it from the Earl of Emsworth’s museum. “I did it with a slice of cold beef and a pickle,” he explained; and Baxter found himself realizing that that was the only way. “Now watch me drop it,” said Mr. Peters, closing one eye and taking aim at the castle. “I have to do this by the doctor’s orders.”

He loosed the bomb and immediately Baxter was lying in bed watching it drop. He was frightened, but the idea of moving did not occur to him. The bomb fell very slowly, dipping and fluttering like a feather. It came closer and closer. Then it struck with a roar and a sheet of flame.

Baxter woke to a sound of tumult and crashing. For a moment he hovered between dreaming and waking, and then sleep passed from him, and he was aware that something noisy and exciting was in progress in the hall below.

Coming down to first causes, the only reason why collisions of any kind occur is because two bodies defy Nature’s law that a given spot on a given plane shall at a given moment of time be occupied by only one body.

There was a certain spot near the foot of the great staircase which Ashe, going downstairs, and George Emerson, coming up, had to pass on their respective routes. George reached it at one minute and three seconds after two a.m., moving silently but swiftly; and Ashe, also maintaining a good rate of speed, arrived there at one minute and four seconds after the hour, when he ceased to walk and began to fly, accompanied by George Emerson, now going down. His arms were round George’s neck and George was clinging to his waist.

In due season they reached the foot of the stairs and a small table, covered with occasional china and photographs in frames, which stood adjacent to the foot of the stairs. That—especially the occasional china—was what Baxter had heard.

George Emerson thought it was a burglar. Ashe did not know what it was, but he knew he wanted to shake it off; so he insinuated a hand beneath George’s chin and pushed upward. George, by this time parted forever from the tongue, the bread, the knife, the fork, the salt, the corkscrew and the bottle of white wine, and having both hands free for the work of the moment, held Ashe with the left and punched him in the ribs with the right.

Ashe, removing his left arm from George’s neck, brought it up as a reënforcement to his right, and used both as a means of throttling George. This led George, now permanently underneath, to grasp Ashe’s ears firmly and twist them, relieving the pressure on his throat and causing Ashe to utter the first vocal sound of the evening, other than the explosive Ugh! that both had emitted at the instant of impact.

Ashe dislodged George’s hands from his ears and hit George in the ribs with his elbow. George kicked Ashe on the left ankle. Ashe rediscovered George’s throat and began to squeeze it afresh, and a pleasant time was being had by both when the Efficient Baxter, whizzing down the stairs, tripped over Ashe’s legs, shot forward and cannoned into another table, also covered with occasional china and photographs in frames.

The hall at Blandings Castle was more an extra drawing-room than a hall; and Lady Ann Warblington, when not nursing a sick headache in her bedroom, would dispense afternoon tea there to her guests. Consequently it was dotted pretty freely with small tables. There were, indeed, no fewer than five more in various spots, waiting to be bumped into and smashed.

The bumping into and smashing of small tables, however, is a task that calls for plenty of time—a leisured pursuit; and neither George nor Ashe, a third party having been added to their little affair, felt a desire to stay on and do the thing properly. Ashe was strongly opposed to being discovered and called on to account for his presence there at that hour; and George, conscious of the tongue and its adjuncts now strewn about the hall, had a similar prejudice against the tedious explanations that detection must involve.

As though by mutual consent each relaxed his grip. They stood panting for an instant; then, Ashe in the direction where he supposed the green-baize door of the servants’ quarters to be, George to the staircase that led to his bedroom, they went away from that place.

They had hardly done so when Baxter, having disassociated himself from the contents of the table he had upset, began to grope his way toward the electric-light switch, the same being situated near the foot of the main staircase. He went on all fours, as a safer, though slower, method of locomotion than the one he had attempted before.

Noises began to make themselves heard on the floors above. Roused by the merry crackle of occasional china, the house party was bestirring itself to investigate. Voices sounded, muffled and inquiring.

Meantime, Baxter crawled steadily on his hands and knees toward the light switch. He was in much the same condition as a White Hope of the ring after he has put his chin in the way of the fist of a rival member of the Truck Drivers’ Union. He knew that he was still alive. More he could not say. The mists of sleep, which still shrouded his brain, and the shake-up he had had from his encounter with the table, a corner of which he had rammed with the top of his head, combined to produce a dreamlike state.

And so the Efficient Baxter crawled on; and as he crawled his hand, advancing cautiously, fell on something—something that was not alive; something clammy and ice-cold, the touch of which filled him with nameless horror.

To say that Baxter’s heart stood still would be physiologically inexact. The heart does not stand still. Whatever the emotions of its owner, it goes on beating. It would be more accurate to say that Baxter felt like a man taking his first ride in an express elevator, who has outstripped his vital organs by several floors and sees no immediate prospect of their ever catching up with him again. There was a great cold void where the more intimate parts of his body should have been. His throat was dry and contracted. The flesh of his back crawled, for he knew what it was he had touched.

Painful and absorbing as had been his encounter with the table, Baxter had never lost sight of the fact that close beside him a furious battle between unseen forces was in progress. He had heard the bumping and the thumping and the tense breathing even as he picked occasional china from his person. Such a combat, he had felt, could hardly fail to result in personal injury to either the party of the first part or the party of the second part, or both. He knew now that worse than mere injury had happened and that he knelt in the presence of death.

There was no doubt that the man was dead. Insensibility alone could never have produced this icy chill. He raised his head in the darkness, and cried aloud to those approaching. He meant to cry: “Help! Murder!” But fear prevented clear articulation. What he shouted was: “Heh! Mer!” On which, from the neighborhood of the staircase, somebody began to fire a revolver.

The Earl of Emsworth had been sleeping a sound and peaceful sleep when the imbroglio began downstairs. He sat up and listened. Yes; undoubtedly burglars! He switched on his light and jumped out of bed. He took a pistol from a drawer, and thus armed went to look into the matter. The dreamy peer was no poltroon.

It was quite dark when he arrived on the scene of conflict in the van of a mixed bevy of pyjamaed and dressing-gowned relations. He was in the van because, meeting these relations in the passage above, he had said to them: “Let me go first. I have a pistol.” And they had let him go first. They were, indeed, awfully nice about it, not thrusting themselves forward or jostling or anything, but behaving in a modest and self-effacing manner that was pretty to watch.

When Lord Emsworth said, “Let me go first,” young Algernon Wooster, who was on the very point of leaping to the fore, said, “Yes, by Jove! Sound scheme, by Gad!”—and withdrew into the background; and the Bishop of Godalming said: “By all means, Clarence—undoubtedly; most certainly precede us.”

When his sense of touch told him he had reached the foot of the stairs, Lord Emsworth paused. The hall was very dark and the burglars seemed temporarily to have suspended activities. And then one of them, a man with a ruffianly, grating voice, spoke. What it was he said Lord Emsworth could not understand. It sounded like “Heh! Mer!”—probably some secret signal to his confederates. Lord Emsworth raised his revolver and emptied it in the direction of the sound.

Extremely fortunately for him, the Efficient Baxter had not changed his all-fours attitude. This undoubtedly saved Lord Emsworth the worry of engaging a new secretary. The shots sang above Baxter’s head one after the other, six in all, and found other billets than his person. They disposed themselves as follows: The first shot broke a window and whistled out into the night; the second shot hit the dinner gong and made a perfectly extraordinary noise, like the Last Trump; the third, fourth and fifth shots embedded themselves in the wall; the sixth and final shot hit a life-size picture of his lordship’s maternal grandmother in the face and improved it out of all knowledge.

One thinks no worse of Lord Emsworth’s maternal grandmother because she looked like Eddie Foy, and had allowed herself to be painted, after the heavy classic manner of some of the portraits of a hundred years ago, in the character of Venus—suitably draped, of course—rising from the sea; but it was beyond the possibility of denial that her grandson’s bullet permanently removed one of Blandings Castle’s most prominent eyesores.

Having emptied his revolver, Lord Emsworth said, “Who is there? Speak!” in rather an aggrieved tone, as though he felt he had done his part in breaking the ice, and it was now for the intruder to exert himself and bear his share of the social amenities.

The Efficient Baxter did not reply. Nothing in the world could have induced him to speak at that moment, or to make any sound whatsoever that might betray his position to a dangerous maniac who might at any instant reload his pistol and resume the fusillade. Explanations, in his opinion, could be deferred until somebody had the presence of mind to switch on the lights. He flattened himself on the carpet and hoped for better things. His cheek touched the corpse beside him; but though he winced and shuddered he made no outcry. After those six shots he was through with outcries.

A voice from above, the bishop’s voice, said: “I think you have killed him, Clarence.”

Another voice, that of Colonel Horace Mant, said:

“Switch on those dashed lights! Why doesn’t somebody? Dash it!”

The whole strength of the company began to demand light.

When the lights came, it was from the other side of the hall. Six revolver shots, fired at quarter past two in the morning, will rouse even sleeping domestics. The servants’ quarters were buzzing like a hive. Shrill feminine screams were puncturing the air. Mr. Beach, the butler, in a suit of pink silk pyjamas, of which none would have suspected him, was leading a party of men servants down the stairs—not so much because he wanted to lead them as because they pushed him.

The passage beyond the green-baize door became congested, and there were cries for Mr. Beach to open it and look through and see what was the matter; but Mr. Beach was smarter than that and wriggled back so that he no longer headed the procession. This done, he shouted:

“Open that door there! Open that door! Look and see what the matter is.”

Ashe opened the door. Since his escape from the hall he had been lurking in the neighborhood of the green-baize door and had been engulfed by the swirling throng. Finding himself with elbow-room for the first time, he pushed through, swung the door open and switched on the lights.

They shone on a collection of semi-dressed figures, crowding the staircase; on a hall littered with china and glass; on a dented dinner gong; on a retouched and improved portrait of the late Countess of Emsworth; and on the Efficient Baxter, in an overcoat and rubber-soled shoes, lying beside a cold tongue. At no great distance lay a number of other objects—a knife, a fork, some bread, salt, a corkscrew and a bottle of white wine.

Using the word in the sense of saying something coherent, the Earl of Emsworth was the first to speak. He peered down at his recumbent secretary and said: “Baxter! My dear fellow—what the devil?”

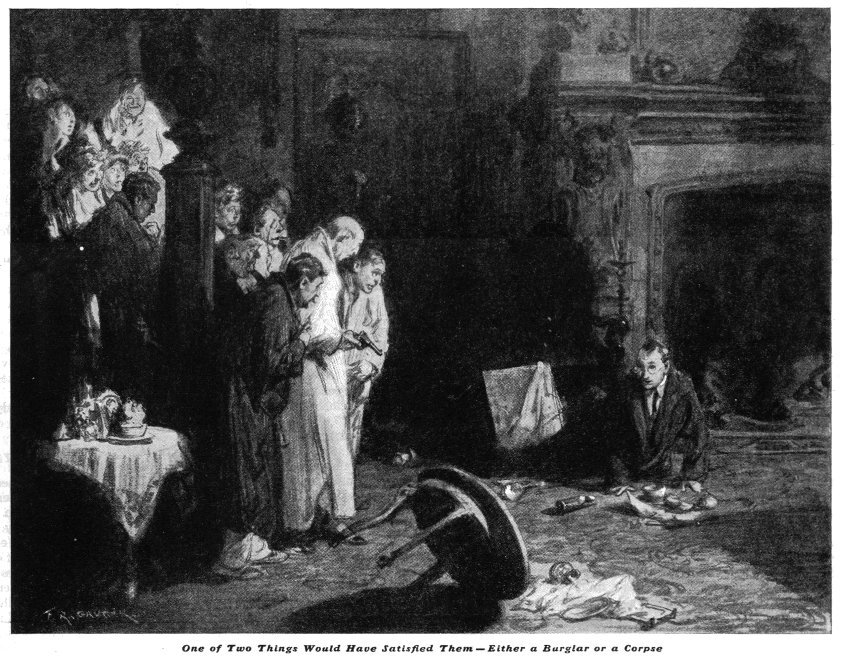

The feeling of the company was one of profound disappointment. They were disgusted at the anticlimax. For an instant, when the Efficient One did not move, hope began to stir; but as soon as it was seen that he was not even injured gloom reigned. One of two things would have satisfied them—either a burglar or a corpse. A burglar would have been welcome, dead or alive; but if Baxter proposed to fill the part adequately it was imperative that he be dead. He had disappointed them deeply by turning out to be the object of their quest. That he was not even grazed was too much.

There was a cold silence as he slowly raised himself from the floor. As his eyes fell on the tongue, he started and remained gazing fixedly at it. Surprise paralyzed him.

Lord Emsworth was also looking at the tongue and he leaped to a not unreasonable conclusion. He spoke coldly and haughtily; for he was not only annoyed, like the others, at the anticlimax, but offended. He knew that he was not one of your energetic hosts who exert themselves unceasingly to supply their guests with entertainment; but there was one thing on which, as a host, he did pride himself—in the material matters of life he did his guests well; he kept an admirable table.

“My dear Baxter,” he said in the tones he usually reserved for the correction of his son Freddie, “if your hunger is so great that you are unable to wait for breakfast, and have to raid my larder in the middle of the night, I wish to goodness you would contrive to make less noise about it. I do not grudge you the food—help yourself when you please—but do remember that people who have not such keen appetites as yourself like to sleep during the night. A far better plan, my dear fellow, would be to have sandwiches or buns—or whatever you consider most sustaining—sent up to your bedroom.”

Not even the bullets had disordered Baxter’s faculties so much as this monstrous accusation. Explanations pushed and jostled one another in his fermenting brain, but he could not utter them. On every side he met gravely reproachful eyes. George Emerson was looking at him in pained disgust. Ashe Marson’s face was the face of one who could never have believed this had he not seen it with his own eyes. The scrutiny of the knife-and-shoe boy was unendurable.

He stammered. Words began to proceed from him, tripping and stumbling over each other. Lord Emsworth’s frigid disapproval did not relax.

“Pray do not apologize, Baxter. The desire for food is human. It is your boisterous mode of securing and conveying it that I deprecate. Let us all go to bed.”

“But, Lord Emsworth——”

“To bed!” repeated his lordship firmly.

The company began to stream moodily upstairs. The lights were switched off. The Efficient Baxter dragged himself away. From the darkness in the direction of the servants’ door a voice spoke.

“Greedy pig!” said the voice scornfully.

It sounded like the voice of the fresh young knife-and-shoe boy, but Baxter was too broken to investigate. He continued his retreat without pausing.

“Stuffin’ of isself at all hours!” said the voice.

There was a murmur of approval from the unseen throng of domestics.

IX

AS WE grow older and realize more clearly the limitations of human happiness, we come to see that the only real and abiding pleasure in life is to give pleasure to other people. One must assume that the Efficient Baxter had not reached the age when this comes home to a man, for the fact that he had given genuine pleasure to some dozens of his fellow men brought him no balm.

There was no doubt about the pleasure he had given. Once they had got over their disappointment at finding that he was not a dead burglar, the house party rejoiced whole-heartedly at the break in the monotony of life at Blandings Castle. Relations who had not been on speaking terms for years forgot their quarrels and strolled about the grounds in perfect harmony, abusing Baxter. The general verdict was that he was insane.

“Don’t tell me that young fellow’s all there,” said Colonel Horace Mant; “because I know better. Have you noticed his eye? Furtive! Shifty! Nasty gleam in it. Besides—dash it!—did you happen to take a look at the hall last night after he had been there? It was in ruins, my dear sir—absolute dashed ruins. It was positively littered with broken china and tables that had been bowled over. Don’t tell me that was just an accidental collision in the dark.

“My dear sir, the man must have been thrashing about—absolutely thrashing about, like a dashed salmon on a dashed hook. He must have had a paroxysm of some kind—some kind of a dashed fit.

“A doctor could give you the name for it. It’s a well-known form of insanity. Paranoia—isn’t that what they call it? Rush of blood to the head, followed by a general running amuck.

“I’ve heard fellows who have been in India talk of it. Natives get it. Don’t know what they’re doing, and charge through the streets taking cracks at people with dashed whacking great knives. Same with this young man, probably in a modified form at present. He ought to be in a home. One of these nights, if this grows on him, he will be massacring Emsworth in his bed.”

“My dear Horace!” The Bishop of Godalming’s voice was properly horror-stricken; but there was a certain unctuous relish in it.

“Take my word for it! Though, mind you, I don’t say they aren’t well suited. Everyone knows that Emsworth has been, to all practical intents and purposes, a dashed lunatic for years. What was it that young fellow Emerson, Freddie’s American friend, was saying, the other day about some acquaintance of his who is not quite right in the head? Nobody in the house—was that it? Something to that effect, at any rate. I felt at the time it was a perfect description of Emsworth.”

“My dear Horace! Your father-in-law! The head of the family!”

“A dashed lunatic, my dear sir—head of the family or no head of the family. A man as absent-minded as he is has no right to call himself sane. Nobody in the house—I recollect it now—nobody in the house except the gas, and that has not been turned on. That’s Emsworth!”

The Efficient Baxter, who had just left his presence, was feeling much the same about his noble employer. After a sleepless night he had begun at an early hour to try to corner Lord Emsworth in order to explain to him the true inwardness of last night’s happenings. Eventually he had tracked him to the museum, where he found him happily engaged in painting a cabinet of birds’ eggs. He was seated on a small stool, a large pot of red paint on the floor beside him, dabbing at the cabinet with a dripping brush. He was absorbed and made no attempt whatever to follow his secretary’s remarks.

For ten minutes Baxter gave a vivid picture of his vigil and the manner in which it had been interrupted.

“Just so; just so, my dear fellow,” said the earl when he had finished. “I quite understand. All I say is, if you do require additional food in the night let one of the servants bring it to your room before bedtime; then there will be no danger of these disturbances. There is no possible objection to your eating a hundred meals a day, my good Baxter, provided you do not rouse the whole house over them. Some of us like to sleep during the night.”

“But, Lord Emsworth! I have just explained—— It was not—I was not——”

“Never mind, my dear fellow; never mind. Why make such an important thing of it? Many people like a light snack before actually retiring. Doctors, I believe, sometimes recommend it. Tell me, Baxter, how do you think the museum looks now? A little brighter? Better for the dash of color? I think so. Museums are generally such gloomy places.”

“Lord Emsworth, may I explain once again?”

The earl looked annoyed.

“My dear Baxter, I have told you that there is nothing to explain. You are getting a little tedious. . . . What a deep, rich red this is, and how clean new paint smells! Do you know, Baxter, I have been longing to mess about with paint ever since I was a boy! I recollect my old father’s beating me with a walking stick. . . . That would be before your time, of course. By the way, if you see Freddie, will you tell him I want to speak to him? He probably is in the smoking room.”

It was an overwrought Baxter who delivered the message to the Honorable Freddie, who, as predicted, was in the smoking room, lounging in a deep armchair.

There are times when life presses hard on a man, and it pressed hard on Baxter now. Fate had played him a sorry trick. It had put him in a position where he had to choose between two courses, each as disagreeable as the other: He must either face a possible second fiasco like that of last night, or else he must abandon his post and cease to mount guard over his threatened treasure.

His imagination quailed at the thought of a repetition of last night’s horrors. He had been badly shaken by his collision with the table and even more so by the events that had followed it. Those revolver shots still rang in his ears.

It was probably the memory of those shots that turned the scale. It was unlikely he would again become entangled with a man bearing a tongue and the other things—he had given up in despair the attempt to unravel the mystery of the tongue; it completely baffled him—but it was by no means unlikely that if he spent another night in the gallery looking on the hall he might again become a target for Lord Emsworth’s irresponsible firearm. Nothing, in fact, was more likely; for in the disturbed state of the public mind the slightest sound after nightfall would be sufficient cause for a fusillade.

He had actually overheard young Algernon Wooster telling Lord Stockheath he had a jolly good mind to sit on the stairs that night with a shotgun, because it was his opinion that there was a jolly sight more in this business than there seemed to be; and what he thought of the bally affair was that there was a gang of some kind at work, and that that feller—what’s-his-name?—that feller Baxter was some sort of an accomplice.

With these things in his mind Baxter decided to remain that night in the security of his bedroom. He had lost his nerve. He formed this decision with the utmost reluctance, for the thought of leaving the road to the museum clear for marauders was bitter in the extreme. If he could have overheard a conversation between Joan Valentine and Ashe Marson it is probable he would have risked Lord Emsworth’s revolver and the shotgun of the Honorable Algernon Wooster.

Ashe, when he met Joan and recounted the events of the night, at which Joan, who was a sound sleeper, had not been present, was inclined to blame himself as a failure. True, fate had been against him, but the fact remained that he had achieved nothing. Joan, however, was not of this opinion.

“You have done wonders,” she said. “You have cleared the way for me. That is my idea of real teamwork. I’m so glad now that we formed our partnership. It would have been too bad if I had got all the advantage of your work and had jumped in and deprived you of the reward. As it is, I shall go down and finish the thing off to-night with a clear conscience.”

“You can’t mean that you dream of going down to the museum to-night!”

“Of course I do.”

“But it’s madness!”

“On the contrary, to-night is the one night when there ought to be no risk.”

“After what happened last night?”

“Because of what happened last night. Do you imagine Mr. Baxter will dare to stir from his bed after that? If ever there was a chance of getting this thing finished, it will be to-night.”

“You’re quite right. I never looked at it in that way. Baxter wouldn’t risk a second disaster. I’ll certainly make a success of it this time.”

Joan raised her eyebrows.

“I don’t quite understand you, Mr. Marson. Do you propose to try to get the scarab to-night?”

“Yes. It will be as easy as——”

“Are you forgetting that, by the terms of our agreement, it is my turn?”

“You surely don’t intend to hold me to that?”

“Certainly I do.”

“But, good heavens! Consider my position! Do you seriously expect me to lie in bed while you do all the work, and then to take a half share in the reward?”

“I do.”

“It’s ridiculous!”

“It’s no more ridiculous than that I should do the same. Mr. Marson, there’s no use in our going over all this again. We settled it long ago.”

Joan refused to discuss the matter further, leaving Ashe in a condition of anxious misery comparable only to that which, as night began to draw near, gnawed the vitals of the Efficient Baxter.

Breakfast at Blandings Castle was an informal meal. There was food and drink in the long dining hall for such as were energetic enough to come down and get it; but the majority of the house party breakfasted in their rooms, Lord Emsworth, whom nothing in the world would have induced to begin the day in the company of a crowd of his relations, most of whom he disliked, setting them the example.

When, therefore, Baxter, yielding to Nature after having remained awake until the early morning, fell asleep at nine o’clock, nobody came to rouse him. He did not ring his bell, so he was not disturbed; and he slept on until half past eleven, by which time, it being Sunday morning and the house party including one bishop and several of the minor clergy, most of the occupants of the place had gone off to church.

Baxter shaved and dressed hastily, for he was in state of nervous apprehension. He had wakened with a presentiment. Something told him the scarab had been stolen in the night, and he wished now that he had risked all and kept guard.

The house was very quiet as he made his way rapidly to the hall. As he passed a window he perceived Lord Emsworth, in an un-Sabbatarian suit of tweeds and bearing a garden fork—which must have pained the bishop—bending earnestly over a flower bed; but he was the only occupant of the grounds, and indoors there was a feeling of emptiness. The hall had that Sunday-morning air of wanting to be left to itself, and disapproving of the entry of anything human until lunch time, which can be felt only by a guest in a large house who remains at home when his fellows have gone to church.

The portraits on the walls, especially the one of the late Countess of Emsworth in the character of Venus rising from the sea, stared at Baxter as he entered, with cold reproof. The very chairs seemed distant and unfriendly; but Baxter was in no mood to appreciate their attitude. His conscience slept. His mind was occupied, to the exclusion of all other things, by the scarab and its fate. Long before he opened the museum door he was feeling the absolute certainty that the worst had happened.

It had. The card which announced that here was an Egyptian scarab of the reign of Cheops of the Fourth Dynasty, presented by J. Preston Peters, Esquire, still lay on the cabinet in its wonted place; but the scarab was gone.

For all that he had expected this, for all his premonition of disaster, it was an appreciable time before the Efficient Baxter rallied from the blow. He stood transfixed, goggling at the empty place.

Then his mind resumed its functions. All, he perceived, was not yet lost. Baxter the watchdog must retire, to be succeeded by Baxter the sleuthhound. He had been unable to prevent the theft of the scarab, but he might still detect the thief.

For the Doctor Watsons of this world, as opposed to the Sherlock Holmeses, success in the province of detective work must always be, to a very large extent, the result of luck. Sherlock Holmes can extract a clew from a wisp of straw or a flake of cigar ash; but Doctor Watson has to have it taken out for him and dusted, and exhibited clearly, with a label attached.

The average man is a Doctor Watson. We are wont to scoff in a patronizing manner at that humble follower of the great investigator; but as a matter of fact we should have been just as dull ourselves. We should not even have risen to the modest height of a Scotland Yard bungler.

Baxter was a Doctor Watson. What he wanted was a clew; but it is hard for the novice to tell what is a clew and what is not. And then he happened to look down—and there on the floor was a clew that nobody could have overlooked.

Baxter saw it, but did not immediately recognize it for what it was. What he saw, at first, was not a clew, but just a mess. He had a tidy soul and abhorred messes, and this was a particularly messy mess. A considerable portion of the floor was a sea of red paint. The can from which it had flowed was lying on its side near the wall. He had noticed that the smell of paint had seemed particularly pungent, but had attributed this to a new freshet of energy on the part of Lord Emsworth. He had not perceived that paint had been spilled.

“Pah!” said Baxter.

Then suddenly, beneath the disguise of the mess, he saw the clew. A footmark! No less. A crimson footmark on the polished wood! It was as clear and distinct as though it had been left there for the purpose of assisting him. It was a feminine footmark, the print of a slim and pointed shoe.

This perplexed Baxter. He had looked on the siege of the scarab as an exclusively male affair. But he was not perplexed long. What could be simpler than that Mr. Peters should have enlisted female aid? The female of the species is more deadly than the male. Probably she makes a better purloiner of scarabs.

Inspiration came to him. Aline Peters had a maid! What more likely than that secretly she should be a hireling of Mr. Peters, on whom he had now come to look as a man of the blackest and most sinister character? Mr. Peters was a collector; and when a collector makes up his mind to secure a treasure he employs, Baxter knew, every possible means to that end.

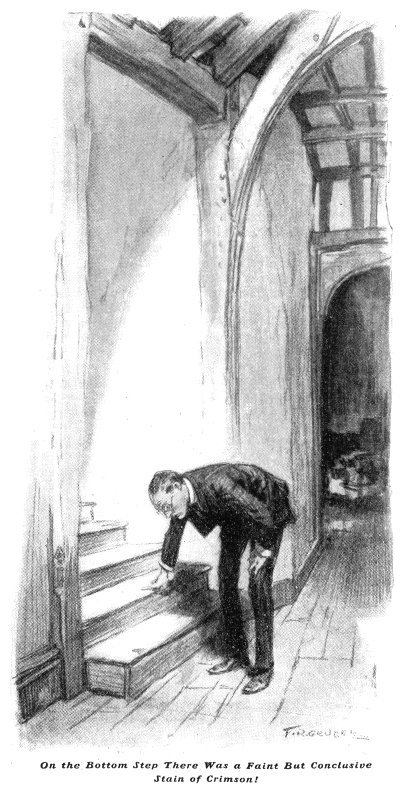

Baxter was now in a state of great excitement. He was hot on the scent and his brain was working like a buzz saw in an ice box. According to his reasoning, if Aline Peters’ maid had done this thing there should be red paint in the hall marking her retreat, and possibly a faint stain on the stairs leading to the servants’ bedrooms.

He hastened from the museum and subjected the hall to a keen scrutiny. Yes; there was red paint on the carpet. He passed through the green-baize door and examined the stairs. On the bottom step there was a faint but conclusive stain of crimson! He was wondering how best to follow up this clew when he perceived Ashe coming down the stairs.

There are moments when the giddy

excitement of being right on the trail causes the amateur—or

Watsonian—detective to be incautious. If Baxter had been wise he would have

achieved his object—the getting a glimpse of Joan’s shoes—by a devious and

snaky route. As it was, zeal getting the better of prudence, he rushed

straight on. His early suspicion of Ashe had been temporarily obscured. Whatever

Ashe’s claims to be a suspect, it had not been his footprint Baxter had seen in

the museum.

There are moments when the giddy

excitement of being right on the trail causes the amateur—or

Watsonian—detective to be incautious. If Baxter had been wise he would have

achieved his object—the getting a glimpse of Joan’s shoes—by a devious and

snaky route. As it was, zeal getting the better of prudence, he rushed

straight on. His early suspicion of Ashe had been temporarily obscured. Whatever

Ashe’s claims to be a suspect, it had not been his footprint Baxter had seen in

the museum.

“Here, you!” said the Efficient Baxter excitedly.

“Sir?”

“The shoes!”

“I beg your pardon?”

“I wish to see the servants’ shoes. Where are they?”

“I expect they have them on, sir. I have noticed that they wear them during the day.”

“Yesterday’s shoes, man—yesterday’s shoes. Where are they?”

“Where are the shoes of yesteryear?” murmured Ashe. “I should say at a venture, sir, that they would be in a large basket somewhere near the kitchen. Our genial knife-and-shoe boy collects them, I believe, at early dawn.”

“Would they have been cleaned yet?”

“If I know the lad, sir—no.”

“Go and bring that basket to me. Bring it to me in this room.”

The room to which he referred was none other than the private sanctum of Mr. Beach, the butler, the door of which, standing open, showed it to be empty. It was not Baxter’s plan, excited as he was, to risk being discovered sifting shoes in the middle of a passage in the servants’ quarters.

Ashe’s brain was working rapidly as he made for the shoe cupboard, that little den of darkness and smells, where Billy, the knife-and-shoe boy, better known in the circle in which he moved as Young Bonehead, pursued his menial tasks. What exactly was at the back of the Efficient Baxter’s mind prompting these maneuvers he did not know; but that there was something he was certain.

He had not yet seen Joan this morning, and he did not know whether or not she had carried out her resolve of attempting to steal the scarab on the previous night; but this activity and mystery on the part of their enemy must have some sinister significance. He gathered up the shoe basket thoughtfully.

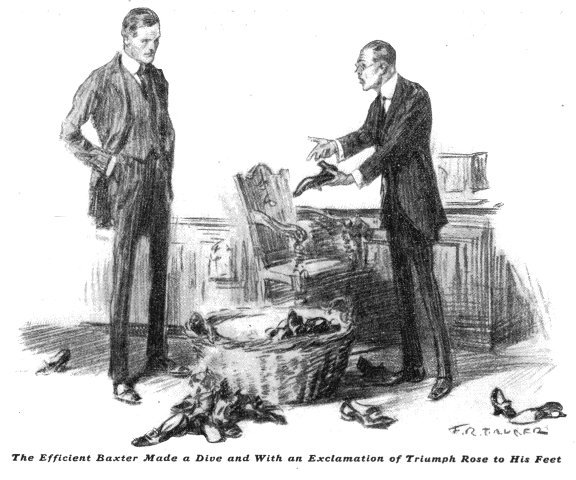

He staggered back with it and dumped it down on the floor of Mr. Beach’s room. The Efficient Baxter stooped eagerly over it. Ashe, leaning against the wall, straightened the creases in his clothes and flicked disgustedly at an inky spot which the journey had transferred from the basket to his coat.

“We have here, sir,” he said, “a fair selection of our various foot coverings.”

“You did not drop any on your way?”

“Not one, sir.”

The Efficient Baxter uttered a grunt of satisfaction and bent once more to his task. Shoes flew about the room. Baxter knelt on the floor beside the basket and dug like a terrier at a rat hole. At last he made a dive and with an exclamation of triumph rose to his feet. In his hand he held a shoe.

“Put those back,” he said.

“Put those back,” he said.

Ashe began to pick up the scattered footgear.

“That’s the lot, sir,” he said, rising.

“Now come with me. Leave the basket there. You can carry it back when you return.”

“Shall I put back that shoe, sir?”

“Certainly not. I shall take this one with me.”

“Shall I carry it for you, sir?”

Baxter reflected.

“Yes. I think that would be best.”

Trouble had shaken his nerve. He was not certain that there might not be others besides Lord Emsworth in the garden; and it occurred to him that, especially after his reputation for eccentric conduct had been so firmly established by his misfortunes that night in the hall, it might cause comment should he appear before them carrying a shoe.

Ashe took the shoe and, doing so, understood what before had puzzled him. Across the toe was a broad splash of red paint. Though he had nothing else to go on, he saw all. The shoe he held was a female shoe. His own researches in the museum had made him aware of the presence there of red paint. It was not difficult to build up on these data a pretty accurate estimate of the position of affairs.

“Come with me,” said Baxter.

He left the room. Ashe followed him.

In the garden Lord Emsworth, garden fork in hand, was dealing summarily with a green young weed that had incautiously shown its head in the middle of a flower bed. He listened to Baxter’s statement with more interest than he usually showed in anybody’s statements. He resented the loss of the scarab, not so much on account of its intrinsic worth as because it had been the gift of his friend Mr. Peters.

“Indeed!” he said, when Baxter had finished. “Really? Dear me! It certainly seems—— It is extremely suggestive. You are certain there was red paint on this shoe?”

“I have it with me. I brought it on purpose to show you.” He looked at Ashe, who stood in close attendance. “The shoe!”

Lord Emsworth polished his glasses and bent over the exhibit.

“Ah!” he said. “Now let me look at—— This, you say, is the—— Just so; just so! Just—— My dear Baxter, it may be that I have not examined this shoe with sufficient care, but—— Can you point out to me exactly where this paint is?”

The Efficient Baxter stood staring at the shoe with wild, fixed stare. Of any suspicion of paint, red or otherwise, it was absolutely and entirely innocent!

(TO BE CONTINUED)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums