The Saturday Evening Post, August 7, 1915

IX—(Continued)

THE shoe became the center of attraction, the cynosure of all eyes. The Efficient Baxter fixed it with the piercing glare of one who feels that his brain is tottering. Lord Emsworth looked at it with a mildly puzzled expression. Ashe Marson examined it with a sort of affectionate interest, as though he were waiting for it to do a trick of some kind. Baxter was the first to break the silence.

“There was paint on this shoe,” he said vehemently. “I tell you there was a splash of red paint across the toe. This man here will bear me out in this. You saw paint on this shoe?”

“Paint, sir?”

“What! Do you mean to tell me you did not see it?”

“No, sir; there was no paint on this shoe.”

“This is ridiculous. I saw it with my own eyes. It was a broad splash right across the toe.”

Lord Emsworth interposed.

“You must have made a mistake, my dear Baxter. There is certainly no trace of paint on this shoe. These momentary optical delusions are, I fancy, not uncommon. Any doctor will tell you——”

“I had an aunt, your lordship,” said Ashe chattily, “who was remarkably subject——”

“It is absurd! I cannot have been mistaken,” said Baxter. “I am positively certain the toe of this shoe was red when I found it.”

“It is quite black now, my dear Baxter.”

“A sort of chameleon shoe,” murmured Ashe.

The goaded secretary turned on him.

“What did you say?”

“Nothing, sir.”

Baxter’s old suspicion of this smooth young man came surging back to him.

“I strongly suspect you of having had something to do with this.”

“Really, Baxter,” said the earl, “that is surely the least probable of solutions. This young man could hardly have cleaned the shoe on his way from the house. A few days ago, when painting in the museum, I inadvertently splashed some paint on my own shoe. I can assure you it does not brush off. It needs a very systematic cleaning before all traces are removed.”

“Exactly, your lordship,” said Ashe. “My theory, if I may——”

“Yes?”

“My theory, your lordship, is that Mr. Baxter was deceived by the light-and-shade effects on the toe of the shoe. The noonday sun, streaming in through the window, must have shone on the shoe in such a manner as to give it a momentary and fictitious aspect of redness. If Mr. Baxter recollects, he did not look long at the shoe. The picture on the retina of the eye consequently had not time to fade. I myself remember thinking at the moment that the shoe appeared to have a certain reddish tint. The mistake——”

“Bah!” said Baxter shortly.

Lord Emsworth, now thoroughly bored with the whole affair and desiring nothing more than to be left alone with his weeds and his garden fork, put in his word. Baxter, he felt, was curiously irritating these days. He always seemed to be bobbing up. The Earl of Emsworth was conscious of a strong desire to be free from his secretary’s company. He was efficient, yes—invaluable indeed—he did not know what he should do without Baxter; but there was no denying that his company tended after a while to become a trifle tedious. He took a fresh grip on his garden fork and shifted it about in the air as a hint that the interview had lasted long enough.

“It seems to me, my dear fellow,” he said, “the only explanation that will square with the facts. A shoe that is really smeared with red paint does not become black of itself in the course of a few minutes.”

“You are very right, your lordship,” said Ashe approvingly. “May I go now, your lordship?”

“Certainly—certainly; by all means.”

“Shall I take the shoe with me, your lordship?”

“If you do not want it, Baxter.”

The secretary passed the fraudulent piece of evidence to Ashe without a word; and the latter, having included both gentlemen in a kindly smile, left the garden.

On returning to the butler’s room Ashe’s first act was to remove a shoe from the top of the pile in the basket, place it in a small closet in the wall, and lock the closet.

“Brain,” he said to himself approvingly, “is what one chiefly needs in matters of this kind. Without brain, where are we? The next development will be when Friend Baxter thinks it over and is struck with the brilliant idea that it is just possible the shoe he gave me to carry and the shoe I did carry were not one shoe, but two shoes. Meantime——”

He had not been waiting long when there was a footstep in the passage and Baxter appeared. The possibility—indeed, the certainty—that Ashe had substituted another shoe for the one with the incriminating splash of paint on it had occurred to him almost immediately on leaving the garden. Ashe was in the enemy’s camp. He would naturally do whatever he could to foil him. He perceived now what a mistake it had been to let Ashe take a hand in this affair at all. He chafed at the thought of the tactical error into which too much haste had led him. He came into the room, brisk and peremptory.

“I wish to look at those shoes again,” he said coldly.

Ashe, with a sigh, rose to assist him.

“Sit down,” said Baxter. “I can manage without you.”

Ashe sat down again and watched him with silent interest. The scrutiny irritated the secretary. Ashe, his elbows on his knees and his chin in his hands, was submitting the shoe expert to a contemplative inspection. After fidgeting a few minutes Baxter lodged a complaint.

“Don’t sit there staring at me!”

“I was interested in what you were doing, sir.”

“Never mind! Don’t stare at me in that idiotic way.”

“May I read a book, sir?”

“Yes; read if you like.”

“Thank you, sir.”

Ashe took a volume from the butler’s slenderly stocked shelf. It was entitled Did She Deserve His Love?—by Mrs. Marmaduke Wigfall. He sighed a little as he turned the pages.

Baxter pursued his investigations in the shoe basket. He went through it twice, but both times without success. After the second search he stood up and looked wildly about the room. He was as certain as he could be of anything that the missing piece of evidence was somewhere within those four walls. It was no use asking Ashe point-blank where it was, for he knew Ashe would not tell him. He had by this time placed Ashe definitely as a malefactor.

There was very little cover in the room, even for so small a fugitive as a shoe. He raised the tablecloth and peered beneath the table.

“Are you looking for Mr. Beach, sir?” said Ashe. “I think he has gone to church.”

Baxter, pink with his exertions, fastened a baleful glance on him.

“You had better be careful,” he said.

“Careful, sir?”

“I am not quite such a fool as you imagine.”

The startled surprise in Ashe’s eye at this statement was too much for Baxter. He looked away and resumed his survey of the room. The floor could be acquitted on sight of suspicion of harboring the quarry. His eyes, roaming to and fro, lit on the closet.

“What is in this closet?”

“That closet, sir?”

“Yes; this closet.” He rapped the door irritably.

“I could not say, sir. Mr. Beach, to whom the room belongs, possibly keeps a few odd trifles there. A ball of string, perhaps. Maybe an old pipe or something of the kind. Probably nothing of value or interest.”

“Open it.”

“It appears to be locked, sir.”

“Unlock it.”

“But where is the key?”

Baxter thought for a moment.

“I have my reasons for thinking you are deliberately keeping the contents of that closet from me. I shall break open the door.”

“I’m afraid you must not do that, sir.”

“Are you aware to whom you are speaking?” inquired Baxter acidly.

“Yes, sir; and I know it is not Lord Emsworth, to whom that closet belongs. If you wish to break it open I am afraid you must first get his permission. He is the sole lessee and proprietor of that closet. I am not even the acting manager.”

Baxter paused. He also reflected. Something told him that the breaking up of his belongings would be just one of those things which his dreamy employer might resent as out of place in a private secretary. He was loath, after the incident of the cold tongue and the midnight shots, to go out of his way to risk annoying Lord Emsworth.

On the other hand, there was the maddening thought that if he left this room in search of him, in order to obtain his sanction for the housebreaking work he proposed to carry through, Ashe would be alone in the room. And he knew that if Ashe were left alone in the room he would instantly remove the shoe to some other hiding place. He was perfectly convinced that the missing shoe was in the closet.

He stood chewing these thoughts for a while, Ashe meantime standing in a graceful attitude before the closet, staring into vacancy. Then Baxter was seized with a happy idea. Why should be leave the room at all? If he sent Ashe, then he himself could wait and make certain that the closet was not tampered with.

“Go and find Lord Emsworth,” he said, “and ask him to be good enough to come here for a moment on a matter of urgent importance. Be quick!” he added, as Ashe stood looking at him without making any movement in the direction of the door.

“Quick, sir?” asked Ashe meditatively, as though he had been asked a conundrum.

“Go and find Lord Emsworth at once.” Ashe did not move. “Do you intend to disobey me?” Baxter’s voice was steely.

“Yes, sir.”

“What!”

“I take my stand,” said Ashe, “on a technical point. In any other place than this house your word would be law. I would fly to do your bidding. If you pressed a button I would do the rest. But in Lord Emsworth’s house I cannot do anything except what pleases me or what is ordered by Lord Emsworth. Suppose—to take a parallel case—the army officer commanding the garrison at a naval station went on board a battleship and ordered the crew to splice the jib-boom spanker. It might be an admirable thing for the country that the jib-boom spanker should be spliced at that particular juncture; but the crew would naturally decline to move in the matter until the order came from the commander of the ship. So in my case. If you will go to Lord Emsworth and explain to him how matters stand, and come back to me and say, Lord Emsworth wishes you to go and ask him to be good enough to come to this room on a matter of urgent importance,’ then I shall be only too glad to go and find him. You see my difficulty, sir?”

“Go and fetch Lord Emsworth. I shall not speak again.”

Ashe flicked a speck of dust from his coat sleeve.

“Very well,” said the secretary.

“I can assure you, sir,” said Ashe, “that if there is a shoe in that closet now, there will be a shoe there when you return.” Baxter stalked from the room. “But,” added Ashe pensively as the footsteps died away, “I did not promise that it would be the same shoe.”

He took the key from his pocket, unlocked the closet and took out the shoe. Then he selected another from the basket, and placing that in the closet relocked the door.

His next act was to take from the shelf a piece of string. Attaching one end of this to the shoe he had taken from the closet he went to the window. He flung the closet key into the bushes, then turned to the shoe. On a level with the sill a water pipe was fastened to the wall with an iron band. He tied the other end of the string to this and let the shoe swing free. He noticed with approval when it had stopped swinging that it was hidden from above by the window sill.

He returned to his place by the mantelpiece.

As an afterthought he took another shoe from the basket and thrust it up the chimney. A shower of soot fell into the grate, blackening his hand. The scullery was a few yards down the corridor. He went there and washed off the soot.

When he returned to the butler’s room Baxter was there, and with him the Earl of Emsworth, the latter looking dazed, as though he were not quite equal to the intellectual pressure of the situation. He also looked annoyed. His mild soul was being stirred to wrath by this perpetual interruption. He was beginning to look on his secretary as a malignant person who deliberately invented excuses for breaking up his morning in the open air.

“Where have you been?” asked Baxter sharply.

“I have been washing my hands, sir.”

“Huh!” said Baxter suspiciously.

“Now, my dear Baxter,” said the earl impatiently, “please tell me once again why you have brought me in here. I cannot make head or tail of what you have been saying. Apparently you accuse this young man of keeping his shoes in a closet. Why should you suspect him of keeping his shoes in a closet? And if he wishes to do so, why on earth should not he keep his shoes in a closet? This is a free country.”

“Exactly, your lordship,” said Ashe approvingly.

“It all has to do with the theft of your scarab, Lord Emsworth. Somebody got into the museum and stole the scarab.”

“Ah, yes; ah, yes—so they did. I remember now. You told me. Bad business that, my dear Baxter. Mr. Peters gave me that scarab. He will be most deucedly annoyed if it’s lost. Yes, indeed.”

“Whoever stole it upset the can of red paint and stepped in it.”

“Devilish careless of them. It must have made the dickens of a mess. Why don’t people look where they are walking?”

“I suspect this man of shielding the criminal by hiding her shoe in this closet.”

“Oh, it’s not his own shoes that this young man keeps in closets?”

“It is a woman’s shoe, Lord Emsworth.”

“The deuce it is! Then it was a woman who stole the scarab? Is that the way you figure it out? Bless my soul, Baxter, one wonders what women are coming to nowadays. It’s all this Movement, I suppose. The Vote, and all that—eh? I recollect having a chat with the Marquis of Petersfield some time ago. He is in the Cabinet, and he tells me it is perfectly infernal the way these women carry on. He said sometimes it got to such a pitch, with them waving banners and presenting petitions, and throwing flour and things at a fellow, that if he saw his own mother coming toward him, with a hand behind her back, he would run like a rabbit. Told me so himself.”

“So,” said the Efficient Baxter, cutting in on the flow of speech, “what I wish to do is to break open this closet.”

“Eh? Why?”

“To get the shoe.”

“The shoe? Ah yes. You were telling me.”

“If you have no objection.”

“Objection, my dear fellow? Why should I have any objection? Let me see! What is it you wish to do?”

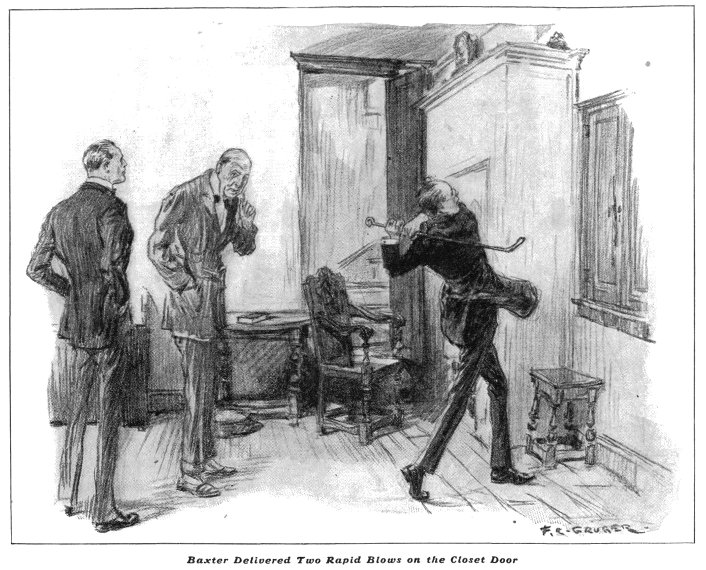

“This,” said Baxter shortly.

He seized the poker from the fireplace and delivered two rapid blows on the closet door. The wood was splintered. A third blow smashed the flimsy lock. The closet, with any skeletons it might contain, was open for all to view. Baxter uttered a cry of triumph and tore the shoe from its resting place. “I told you,” he said; “I told you!”

The next moment he looked up with an exclamation of surprise and anger.

“This shoe has no paint on it,” he said, glaring at Ashe. “This is not the shoe.”

“It certainly appears, sir,” said Ashe sympathetically, “to be free from paint. There is a sort of reddish glow just there, if you look at it sideways,” he added helpfully.

“Are you satisfied now, my dear Baxter,” said the earl, “or is there any more furniture that you would like to break? You know, this furniture breaking is becoming a positive craze with you, my dear fellow. You ought to fight against it. Night before last I don’t know how many tables broken in the hall; and now this closet. You will ruin me. No purse can stand the constant drain.”

The secretary stood still. The disappointment had been severe. A chance remark of Lord Emsworth’s set him off on the trail once more. Lord Emsworth had caught sight of the little pile of soot in the grate. He bent down to inspect it.

“Dear me!” he said. “I must remember to tell Beach to have his chimney swept. It seems to need it badly.”

Baxter’s eye, rolling in a fine frenzy from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven, also focused itself on the pile of soot; and a thrill went through him. Soot in the fireplace! Ashe washing his hands! “You know my methods, my dear Watson. Apply them.”

He dived forward with a rush, nearly knocking Lord Emsworth off his feet, and thrust an arm up into the unknown. An avalanche of soot fell on his hand and wrist; but he ignored it, for at the same instant his fingers had closed on what he was seeking.

“Ah!” he said. “I thought as much. You were not clever enough after all.”

“No, sir,” said Ashe patiently. “We all make mistakes.”

“You would have done better not to give me all this trouble. You have done yourself no good by it.”

“It has been great fun, though, sir,” argued Ashe.

“Fun!” Baxter laughed grimly. “You may have cause to change your opinion of what constitutes——”

His voice failed as his eye fell on the all-black toe of the shoe. He looked up and caught Ashe’s benevolent gaze. He straightened himself and brushed a bead of perspiration from his face with the back of his hand. Unfortunately he used the sooty hand, and the result was like some gruesome burlesque of a negro minstrel.

“Did you put that shoe there?” he asked slowly.

“Yes, sir.”

“Then what did you mean by putting it there?” roared Baxter.

“Animal spirits, sir.”

“What!”

“Animal spirits, sir.”

What the Efficient Baxter would have replied to this one cannot tell. Just as he was opening his mouth, Lord Emsworth, catching sight of his face, intervened.

“My dear Baxter, your face! It is positively covered with soot—positively! You must go and wash it. You are quite black. Really, my dear fellow, you present rather an extraordinary appearance. Run off to your room.”

Against this crowning blow the Efficient Baxter could not stand up. It was the end.

“Soot!” he murmured weakly. “Soot!”

“Your face is covered, my dear fellow—quite covered.”

“It certainly has a faintly sooty aspect, sir,” said Ashe.

His voice roused the sufferer to one last flicker of spirit.

“You will hear more of this,” he said. “You will——”

At this moment, slightly muffled by the intervening door and passageway, there came from the direction of the hall a sound like the delivery of a ton of coal. A heavy body bumped down the stairs, and a voice which all three recognized as that of the Honorable Freddie uttered an oath that lost itself in a final crash and a musical splintering sound, which Baxter for one had no difficulty in recognizing as the dissolution of occasional china.

Even if they had not so able a detective as Baxter with them, Lord Emsworth and Ashe would have been at no loss to guess what had happened. Doctor Watson himself could have deduced it from the evidence. The Honorable Freddie had fallen downstairs.

With a little ingenuity this portion of the story of Mr. Peters’ scarab could be converted into an excellent tract, driving home the perils, even in this world, of absenting oneself from church on Sunday morning. If the Honorable Freddie had gone to church he would not have been running down the great staircase at the castle at that hour; and if he had not been running down the great staircase at the castle at that hour he would not have encountered Muriel.

Muriel was a Persian cat belonging to Lady Ann Warblington. Lady Ann had breakfasted in bed and lain there late, as she rather fancied she had one of her sick headaches coming on. Muriel had left her room in the wake of the breakfast tray, being anxious to be present at the obsequies of a fried sole that had formed Lady Ann’s simple morning meal, and had followed the maid who bore it until she had reached the hall.

At this point the maid, who disliked Muriel, stopped and made a noise like an exploding pop bottle, at the same time taking a little run in Muriel’s direction and kicking at her with a menacing foot. Muriel, wounded and startled, had turned in her tracks and sprinted back up the staircase at the exact moment when the Honorable Freddie, who for some reason was in a great hurry, ran lightly down.

There was an instant when Freddie could have saved himself by planting a number-ten shoe on Muriel’s spine, but even in that crisis he bethought him that he hardly stood solid enough with the authorities to risk adding to his misdeeds the slaughter of his aunt’s favorite cat, and he executed a rapid swerve. The spared cat proceeded on her journey upstairs, while Freddie, touching the staircase at intervals, went on down.

Having reached the bottom, he sat amid

the occasional china, and endeavored to ascertain the extent of his injuries. He

had a dazed suspicion that he was irreparably fractured in a dozen places. It

was in this attitude that the rescue party found him. He gazed up at them with

silent pathos.

Having reached the bottom, he sat amid

the occasional china, and endeavored to ascertain the extent of his injuries. He

had a dazed suspicion that he was irreparably fractured in a dozen places. It

was in this attitude that the rescue party found him. He gazed up at them with

silent pathos.

“In the name of goodness, Frederick,” said Lord Emsworth extremely peevishly, “what do you imagine you are doing?”

Freddie endeavored to rise, but sank back again with a stifled howl.

“It was that bally cat of Aunt Ann’s,” he said. “It came legging it up the stairs. I think I’ve broken my leg.”

“You have certainly broken everything else,” said his father unsympathetically. “Between you and Baxter, I wonder there’s a stick of furniture standing in the house.”

“Thanks, old chap,” said Freddie gratefully as Ashe stepped forward and lent him an arm. “I think my bally ankle must have got twisted. I wish you would give me a hand up to my room.”

“And, Baxter, my dear fellow,” said Lord Emsworth, “you might telephone to Doctor Bird, in Market Blandings, and ask him to be good enough to drive out. I am sorry, Freddie,” he added, “that you have met with this accident; but—but everything is so—so disturbing nowadays that I feel—I feel most disturbed.”

Ashe and the Honorable Freddie began to move across the hall—Freddie hopping, Ashe advancing with a sort of polka step. As they reached the stairs there was a sound of wheels outside and the vanguard of the house party, returned from church, entered the house.

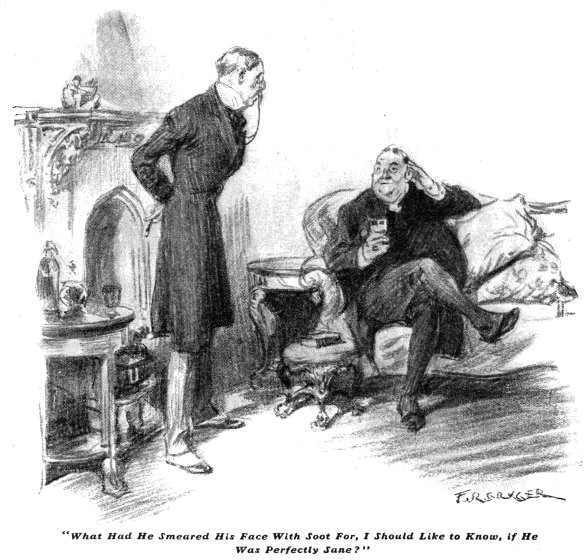

“It’s all very well to give it out

officially that Freddie has fallen downstairs and sprained his ankle,” said

Colonel Horace Mant, discussing the affair with the Bishop of Godalming later

in the afternoon; “but it’s my firm belief that that fellow Baxter did

precisely as I said he would—ran amuck and inflicted dashed frightful injuries

on young Freddie. When I got into the house there was Freddie being helped up

the stairs, while Baxter, with his face covered with soot, was looking after

him with a sort of evil grin. What had he smeared his face with soot for, I

should like to know, if he was perfectly sane?

“It’s all very well to give it out

officially that Freddie has fallen downstairs and sprained his ankle,” said

Colonel Horace Mant, discussing the affair with the Bishop of Godalming later

in the afternoon; “but it’s my firm belief that that fellow Baxter did

precisely as I said he would—ran amuck and inflicted dashed frightful injuries

on young Freddie. When I got into the house there was Freddie being helped up

the stairs, while Baxter, with his face covered with soot, was looking after

him with a sort of evil grin. What had he smeared his face with soot for, I

should like to know, if he was perfectly sane?

“The whole thing is dashed fishy and mysterious; and the sooner I can get Mildred safely out of the place, the better I shall be pleased. The fellow’s as mad as a hatter!”

X

WHEN Lord Emsworth, sighting Mr. Peters in the group of returned churchgoers, drew him aside and broke the news that the valuable scarab, so kindly presented by him to the castle museum, had been stolen in the night by some person unknown, he thought the millionaire took it exceedingly well. Though the stolen object no longer belonged to him, Mr. Peters no doubt still continued to take an affectionate interest in it and might have been excused had he shown annoyance that his gift had been so carelessly guarded.

Mr. Peters was, however, thoroughly magnanimous about the matter. He deprecated the notion that the earl could possibly have prevented this unfortunate occurrence. He quite understood. He was not in the least hurt. Nobody could have foreseen such a calamity. These things happened and one had to accept them. He himself had once suffered in much the same way, the gem of his collection having been removed almost beneath his eyes in the smoothest possible fashion.

Altogether, he relieved Lord Emsworth’s mind very much; and when he had finished doing so he departed swiftly and rang for Ashe. When Ashe arrived he bubbled over with enthusiasm. He was lyrical in his praise. He went so far as to slap Ashe on the back. It was only when the latter disclaimed all credit for what had occurred that he checked the flow of approbation.

“It wasn’t you who got it? Who was it, then?”

“It was Miss Peters’ maid. It’s a long story; but we were working in partnership. I tried for the thing and failed, and she succeeded.”

It was with mixed feelings that Ashe listened while Mr. Peters transferred his adjectives of commendation to Joan. He admired Joan’s courage, he was relieved that her venture had ended without disaster, and he knew that she deserved whatever anyone could find to say in praise of her enterprise: but, at first, though he tried to crush it down, he could not help feeling a certain amount of chagrin that a girl had succeeded where he, though having the advantage of first chance, had failed. The terms of his partnership with Joan had jarred on him from the beginning.

A man may be in sympathy with the modern movement for the emancipation of woman and yet feel aggrieved when a mere girl proves herself a more efficient thief than himself. Woman is invading man’s sphere more successfully every day; but there are still certain fields in which man may consider that he is rightfully entitled to a monopoly—and the purloining of scarabs in the watches of the night is surely one of them. Joan, in Ashe’s opinion, should have played a meeker and less active part.

These unworthy emotions did not last long. Whatever his shortcomings, Ashe possessed a just mind. By the time he had found Joan, after Mr. Peters had said his say and dispatched him below stairs for that purpose, he had purged himself of petty regrets and was prepared to congratulate her whole-heartedly. He was, however, determined that nothing should induce him to share in the reward. On that point, he resolved, he would refuse to be shaken.

“I have just left Mr. Peters,” he began. “All is well. His check book lies before him on the table and he is trying to make his fountain pen work long enough to write a check. But there is just one thing I want to say——”

She interrupted him. To his surprise, she was eying him coldly and with disapproval. “And there is just one thing I want to say,” she said; “and that is, if you imagine I shall consent to accept a penny of the reward——”

“Exactly what I was going to say. Of course I couldn’t dream of taking any of it.”

“I don’t understand you. You are certainly going to have it all. I told you when we made our agreement that I should only take my share if you let me do my share of the work. Now that you have broken that agreement, nothing could induce me to take it. I know you meant it kindly, Mr. Marson; but I simply can’t feel grateful. I told you that ours was a business contract and that I wouldn’t have any chivalry; and I thought that after you had given me your promise——”

“One moment,” said Ashe, bewildered. “I can’t follow this. What do you mean?”

“What do I mean? Why, that you went down to the museum last night before me and took the scarab, though you had promised to stay away and give me my chance.”

“But I didn’t do anything of the sort.”

It was Joan’s turn to look bewildered.

“But you have got the scarab, Mr. Marson?”

“Why, you have got it!”

“No!”

“But—but it has gone!”

“I know. I went down to the museum last night, as we had arranged; and when I got there there was no scarab. It had disappeared.”

They looked at each other in consternation.

“It was gone when you got to the museum?” Ashe asked.

“There wasn’t a trace of it. I took it for granted that you had been down before me. I was furious!”

“But this is ridiculous!” said Ashe. “Who can have taken it? There was nobody besides ourselves who knew Mr. Peters was offering the reward. What exactly happened last night?”

“I waited until one o’clock. Then I slipped down, got into the museum, struck a match, and looked for the scarab. It wasn’t there. I couldn’t believe it at first. I struck some more matches—quite a number—but it was no good. The scarab was gone; so I went back to bed and thought hard thoughts about you. It was silly of me. I ought to have known you would not break your word; but there didn’t seem any other explanation.

“Well, somebody must have taken it; and the question is, what are we to do?” She laughed. “It seems to me that we were a little premature in quarreling about how we were to divide that reward. It looks as though there isn’t going to be any reward.”

“Meantime,” said Ashe gloomily, “I suppose I have got to go back and tell Mr. Peters. It will break his heart.”

XI

BLANDINGS CASTLE dozed in the calm of an English Sunday afternoon. All was peace. Freddie was in bed, with orders from the doctor to stay there until further notice. Baxter had washed his face. Lord Emsworth had returned to his garden fork. The rest of the house party strolled about the grounds or sat in them, for the day was one of those late spring days that are warm with a premature suggestion of midsummer.

Aline Peters was sitting at the open window of her bedroom, which commanded an extensive view of the terraces. A pile of letters lay on the table beside her, for she had just finished reading her mail. The postman came late to the castle on Sundays and she had not been able to do this until luncheon was over.

Aline was puzzled. She was conscious of a fit of depression for which she could in no way account. This afternoon she had a feeling that all was not well with the world, which was the more remarkable because she was usually keenly susceptible to weather conditions and reveled in sunshine like a kitten. Yet here was a day nearly as fine as an American day—and she found no solace in it.

She looked down on the terrace; as she looked the figure of George Emerson appeared, walking swiftly. And at the sight of him something seemed to tell her that she had found the key to her gloom.

There are many kinds of walk. George Emerson’s was the walk of mental unrest. His hands were clasped behind his back, his eyes stared straight in front of him from beneath lowering brows, and between his teeth was an unlighted cigar. Plainly all was not well with George Emerson.

Aline had suspected as much at luncheon; and looking back she realized that it was at luncheon her depression had begun. The discovery startled her a little. She had not been aware, or she had refused to admit to herself, that George’s troubles bulked so large on her horizon. She had always told herself that she liked George, that George was a dear old friend, that George amused and stimulated her; but she would have denied she was so wrapped up in George that the sight of him in trouble would be enough to spoil for her the finest day she had seen since she left America.

There was something not only startling but shocking in the thought; for she was honest enough with herself to recognize that Freddie, her official loved one, might have paced the grounds of the castle chewing an unlighted cigar by the hour without stirring any emotion in her at all.

And she was to marry Freddie next month! This was surely a matter that called for thought. She proceeded, gazing down the while at the perambulating George, to give it thought.

Aline’s was not a deep nature. She had never pretended to herself that she loved the Honorable Freddie in the sense in which the word is used in books. She liked him and she liked the idea of being connected with the peerage; her father liked the idea and she liked her father. And the combination of these likings had caused her to reply “Yes” when, last autumn, Freddie, swelling himself out like an embarrassed frog and gulping, had uttered that memorable speech beginning, “I say, you know, it’s like this, don’t you know!”—and ending, “What I mean is, will you marry me—what?”

She had looked forward to being placidly happy as the Honorable Mrs. Frederick Threepwood. And then George Emerson had reappeared in her life, a disturbing element.

(TO BE CONCLUDED)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums