The Saturday Evening Post, March 18, 1916

STUDENTS of American folklore are doubtless familiar with the quaint old story of Clarence MacFadden. Clarence MacFadden, it seems, “was wishful to dance, but his feet wasn’t gaited that way. So he sought a professor and asked him his price, and said he was willing to pay. The professor”—the legend goes on—“looked down with alarm at his feet, and marked their enormous expanse; and he tacked on a five to his regular price, for teaching MacFadden to dance.”

I have often been struck by the close similarity between Clarence’s case and that of Henry Wallace Mills.

One difference alone presents itself. It would seem to have been mere vanity and ambition that stimulated the former; whereas the motive power that drove Henry Mills to defy Nature and attempt dancing was the purer one of love. He did it to please his wife. Had he never gone to Ye Bonnie Brier Bush Farm and there met Minnie Hill, he would no doubt have continued to spend in peaceful reading the hours not assigned to work at the bank which employed him as one of its paying tellers. For Henry was a voracious reader. His idea of a pleasant evening was to get back to his little flat in Harlem, take off his coat, put on his slippers, light his pipe, and go on from the point where he had left off the night before in his perusal of the Bis-Cal volume of the Encyclopædia Britannica. He read the Bis-Cal volume because he had finished the A-And, the And-Aus, and the Aus-Bis.

In Henry’s method of study there was something worthy of praise, and yet perhaps a little gruesome. He went after learning with the cold and dispassionate relentlessness of a stoat pursuing a rabbit. The ordinary man who is paying installments on the Encyclopædia Britannica is all too apt to get overexcited and to skip impatiently to Volume Twenty-eight—Vet-Zym—to see how it all comes out in the end. Not so Henry. He meant to read the thing through, and he was not going to spoil his pleasure by peeping ahead.

It would seem to be an inexorable law of Nature that no man shall shine at both ends. If he has a high forehead and a thirst for wisdom he is rarely able to fox trot; while if he is a good dancer he is nearly always petrified from the ears up. No better examples of this law could have been found in New York than Henry Mills and his fellow teller, Sidney Mercer. Paying tellers, like bears, lions, tigers and other fauna in captivity, are always shut up in a cage in pairs, and are consequently dependent on each other for entertainment and social intercourse when business is slack.

Henry Mills and Sidney Mercer simply could not find a subject in common. Sidney knew nothing of even such elementary things as Abana, Aberration and Acrogenae; while Henry, on his side, was scarcely aware that there had been any developments in the dance since the polka. It was a relief to him when Sidney threw up his job to join the chorus of a musical comedy and was succeeded by a man who, though full of limitations, could at least converse intelligently on bowling.

Such, then, was Henry Wallace Mills. He was in the middle thirties, temperate, studious, a moderate smoker, and—one would have said—a bachelor of the bachelors, armor-plated against Cupid’s well-intentioned but obsolete artillery. Sometimes Sidney Mercer’s successor in the tellers’ cage, a young man of sentiment, would broach the topic of Woman and Marriage. On such occasions Henry would look at him in a manner that was a blend of scorn, amusement and indignation; and when the other urged Henry to get married and learn the magic of a good woman’s love he would reply with a single word:

“Me!”

It was the way he said it that impressed you.

But Henry had yet to experience the unmanning atmosphere of a lonely summer resort. He had only just reached a position in the bank where he was permitted to take his annual vacation in the summer. Hitherto he had always been released from the cage during the winter months, and had spent his ten days of freedom at his flat, a book in his hand and his feet on the radiator. But the summer after Sidney Mercer’s departure they unleashed him in the heat of July.

It was meltingly warm in the city. Something in Henry cried out for the country. After reading much Summer-Resort literature he decided to go to Ye Bonnie Brier Bush Farm, because the advertisements spoke so well of it.

Ye Bonnie Brier Bush Farm was a rather battered frame building many miles from anywhere. Its attractions included a Lovers’ Leap, a Grotto, a five-hole Golf Links, where the devotee of the sport found unusual hazards in the shape of a number of tethered goats, and a silvery lake, only portions of which were used as a dumping ground for tin cans and old sugar boxes. It was all new and strange to Henry, and caused him an odd exhilaration. Something of gayety and recklessness began to creep into his veins. He had a curious feeling that in these romantic surroundings some adventure ought to happen to him.

At this juncture Minnie Hill arrived. She was a small, slim girl, thinner than she should have been, with large eyes that seemed to Henry pathetic and stirred his chivalry. He began to think a good deal about Minnie Hill. And then one evening, on the shores of the silvery lake, he met her. He was standing there, slapping at things that looked like mosquitoes but could not have been, for the advertisements expressly stated that none were ever found in the vicinity of the farm, when along she came. She walked slowly, as if she were tired. Her pallor struck Henry, and a strange thrill—half pity, half something else—ran through him.

“Good evening,” he said.

It was the first time he had spoken to her. She never contributed to the dialogue of the dining room and he had been too shy to seek her out elsewhere.

She said “Good evening” too—tieing the score. And the conversation flagged for a moment.

Commiseration overcame Henry’s shyness.

“You’re looking tired,” he said.

“I feel tired.” She paused. “I overdid it in the city.”

“It?”

“Dancing.”

“Oh, dancing. Did you dance much?”

“Yes; a great deal.”

“I guess you overdid it.”

“Yes.”

“Yes?”

“Yes.”

A promising, even a dashing start. But how to continue? For the first time since the volumes had been delivered at his flat Henry regretted his steady determination not to read ahead in the Encyclopædia. It would have been pleasant if he could have been in a position to talk easily of Dancing. Then memory reminded him that though he had not yet got up to that, it was only a few weeks since he had been reading of the Ballet, which was practically the same thing.

“I don’t dance myself,” he said.

“No?”

“But I am fond of reading about it. Did you know that the word ballet incorporates three distinct modern words—ballet, ball and ballad. You see, ballet dancing was originally accompanied by singing.”

It hit her. It had her weak. She looked at him with awe in her eyes. One might almost say that she gaped at Henry.

“I hardly know anything,” she said.

“The first descriptive ballet seen in London,” continued Henry quietly, “was The Tavern Bilkers, which was played at Drury Lane in—in seventeen-something.”

“Yes?”

“And the earliest modern ballet on record was that given by—by some one to celebrate the marriage of the Duke of Milan in fourteen-eighty-nine.”

There was no doubt or hesitation about the date this time. He always remembered it because it was his telephone number. He gave it out with a roll, and the girl’s eyes widened.

“What an awful lot you know!”

“Oh, no! No. Oh, no! Of course I read a great deal.”

“It must be splendid to know a lot,” she said wistfully. “I’ve never had time for reading. I’ve always wanted to. I think you’re wonderful.”

Henry’s soul was expanding like a flower and purring like a well-tickled cat. Never in his life had he been admired by a woman. The sensation was intoxicating.

Silence fell on them. They started to walk back to the farm, warned by the distant ringing of a bell that supper was about to materialize. It was not a musical bell, but the magic of that unusual moment lent it charm. The sun was setting. The creatures, unclassified by science, which might have been mistaken for mosquitoes had their presence at Ye Bonnie Brier Bush Farm been possible, were biting harder than ever. But Henry heeded them not. He did not even slap at them. They drank their fill of his blood and went off to put their friends onto this good thing; but for Henry they did not exist. Strange things were happening to him. And, lying awake that night, he recognized the truth. He was in love.

“You’re dead wrong about Love, Mills,” said his sentimental fellow teller shortly after Henry’s return. “I tell you there’s nothing on earth like the love of a good woman. Why don’t you get married?”

“Going to get married,” replied Henry briskly. “Week to-morrow; Li’l’ Church Round Corner.”

Which stunned the other so thoroughly that he gave a customer who entered at the moment fifteen dollars for a ten-dollar check, and had to do some excited telephoning after office hours.

Henry’s first year as a married man was the happiest of his life. He had always heard this period described as the most perilous of matrimony. Even the sentimental teller had admitted that a fellow had to watch out the first year. Henry had braced himself for clashings of tastes, painful adjustments of character, sudden and unavoidable quarrels. Nothing of the kind happened. Minnie merged with his life as smoothly as one river joins another. He did not even have to alter his habits.

Every morning he had his breakfast at eight-fifteen, smoked a cigarette, and walked a block to the Subway. At five he left the bank, and at six he arrived home, for it was his practice to walk the first forty blocks of the way, breathing deeply and regularly. Then dinner. Then the quiet evening. Sometimes the moving pictures, but generally the quiet evening, he reading the Encyclopædia—aloud now—Minnie darning his socks, but never ceasing to listen.

Each day brought the same sense of grateful astonishment that he could be so wonderfully happy, so extraordinarily peaceful. Life was as perfect as it could be. He had not a care in the world and Minnie was looking a different girl. She had lost that drawn look of hers. She was filling out. She was growing prettier daily.

Sometimes he would suspend his reading for a moment and look across at her. At first he would see only her soft hair as she bent over her sewing. Then, wondering at the silence, she would look up and he would meet her big eyes. And then Henry would simmer with happiness and demand of himself silently:

“Can you beat it!”

And then into the middle of his peace fell the dance craze, like a shell.

It began on the anniversary of their wedding. They had celebrated this event in fitting style, with dinner at an Italian restaurant off Seventh Avenue, where the management was so carelessly princely that it threw in a bottle of red wine free, as if it were a mere nothing; and, as if that were not enough, practically gave you the dinner. After this they had gone to a musical comedy. Finally, to wind up in a burst of splendor, they went to supper at a glittering restaurant near Longacre Square.

There was something about supper at an expensive restaurant that had always appealed to Henry’s imagination. Earnest devourer as he was of the solids of literature, he had tasted from time to time its lighter fare—those novels that begin with the hero supping in some glittering resort and having his attention attracted to a distinguished-looking elderly man, with a gray imperial, who is entering with a girl so strikingly beautiful that —— Well, Henry had always liked that sort of thing, and here at Geisenheimer’s he seemed to be getting it.

They had finished supper and he was smoking a cigar—his second that day. As he leaned back in his chair, surveying the scene, he felt braced up, adventurous. He had the feeling, which comes in similar circumstances to all quiet men who like to sit at home and read, that this was the sort of atmosphere in which he really belonged. He liked it all—the brightness of the lights; the music; the movement; the hubbub in which the shrill note of the chorus girl calling to her mate blended with the deep-throated gurgle of the wine agent surprised while drinking soup. All these things stirred Henry deeply. He would be thirty-six on his next birthday, but he felt a youngish twenty-one.

As he sat there a voice spoke at his side:

“Henry, by Heck!”

It was a familiar voice. He looked round, to perceive Sidney Mercer.

The passage of a year, which had turned Henry into a married man, had converted Sidney Mercer into something so wondrous that for a moment the spectacle deprived Henry of breath. Faultless evening dress clung with loving closeness to Sidney’s lissom form. Gleaming shoes of perfect patent leather covered his feet. His light hair was brushed back into a smooth sleekness on which the electric lights shone like stars on some beautiful pool. His practically chinless face beamed amiably over a spotless collar. Henry wore blue serge.

“What are you doing here, Henry, old top?” said the vision. “I didn’t know you ever came among the bright lights.”

His eyes wandered off to Minnie. There was admiration in them, for Minnie was looking her prettiest.

“Wife,” said Henry, recovering speech. And to Minnie: “Mist’ Merce’. Old friend.”

This was not an accurate description of his attitude toward Sidney. Even in the bank, where he had worn paper cuff-protectors, he had disliked him; and now, seeing him all dressed up and very much at his ease in this gay place, he found himself—for no reason that he could discover—disliking him more. It was as if Sidney was a symbol of something menacing to the quiet peace of his orderly life.

“So you’re married? Well, well! Wish you luck, old man! How’s the bank?”

“All right. You still on the stage?”

“Me? No, sir! No stage for me! Got a better job than fooling round at twenty-five per. I’m a professional dancer at this joint. Rolling in the stuff! Why aren’t you dancing?”

The words struck a jarring note. Until that moment the lights and the music had had a subtle psychological effect on Henry, enabling him somehow to hypnotize himself into a belief that it was not inability to dance that kept him in his seat, but he had really had so much of all that sort of thing that, just for a change, he preferred to sit quietly and look on. He was now obliged to face the truth.

“I don’t dance.”

“For the love of Mike! I thought everybody did nowadays. I bet Mrs. Mills does. Would you care to have a turn, Mrs. Mills?”

Minnie shook her head.

“No, thank you—really.”

“Do!”

Remorse began to work on Henry. He felt that he was standing in the way of Minnie’s pleasure. Of course she wanted to dance. All girls did. She was only refusing because she did not like to leave him alone. He achieved a sort of heartiness.

“Don’t be silly, Min. Go to it! I shall be all right. I’ll sit here and smoke.”

The next moment Minnie and her partner had gone, and simultaneously Henry had ceased to feel a youngish twenty-one and was even conscious of a fleeting doubt as to whether he was really only thirty-five.

Boil the whole question of old age down and what it comes to is that a man is young as long as he can dance without getting lumbago; while if he cannot dance he is never young at all. This was the truth that forced itself on Henry as he sat watching Minnie. Even he could see that she danced well. He thrilled at the sight of her gracefulness. For the first time since his marriage he became introspective. It had never struck him before how much younger Minnie was than himself.

When she had signed the paper at the City Hall, on the occasion of the purchase of the license, she had given her age, he remembered now, as twenty-six. At the time it had made no impression on him. Now he saw clearly that between thirty-five and twenty-six there is a gap of nine years; and a chill sensation of being old and stodgy came over him. How dull it must be for poor little Minnie, cooped up night after night with such an old fogy. Other men took their wives out and gave them a good time, dancing half the night with them. All he could do was to sit at home and read Minnie dull stuff from the Encyclopædia.

What a life for the poor child!

The music stopped. They came back to the table—Minnie with a glow on her face that made her look younger than ever; Sidney, the insufferable pill, grinning and smirking and pretending to be about eighteen. An acute envy of Sidney seized Henry Mills. He caught sight of himself in a mirror and was surprised to find that his hair was not white.

Half an hour later, in the cab going home, Minnie, half asleep, was roused by a sudden snort close to her ear. It was Henry Wallace Mills resolving that he would learn to dance.

The mind of man being essentially dramatic, it never even occurred to Henry to confide his resolution to Minnie. That would hopelessly rob the thing of its punch. Her birthday would be coming round in a few weeks, to be attended with celebrations exactly similar to those of the wedding anniversary; and not till they were seated once more in Geisenheimer’s on that distant night did Henry intend to breathe a word of his plans. He would spring the completed thing on her abruptly as a wonderful birthday present.

Natural as this resolve may have been, it was the cause of complicating life a good deal. He had narrow escapes. Once, when he was practicing the one-step in the parlor—he had bought a half-dollar book entitled The A-B-C of Modern Dancing, by “Tango,” and studied the plates at the office—she came in from the kitchen to ask if he wanted the steak rare; and only the statement, in a moment of inspiration, that he was suffering from a touch of cramp could appease her curiosity.

And then there was the question of how to fit the lessons into his day. He had had no difficulty about finding an instructor. The papers were full of their advertisements. He selected a Madame Gavarni because she lived at a convenient spot. A Subway express station stood at the end of her street. The difficulty was that his life until now had run on such a regular schedule that he could hardly alter so important an item as the hour of his arrival home without exciting comment. Only deceit could provide a solution. It was not easy to force himself to practicing deceit with Minnie; but he did it.

“Min, dear!” he said at breakfast.

“Yes, Henry?”

Henry blushed. He was bracing himself for his first lie to her.

“I’ve got an idea that I’m not getting enough exercise.”

“Why, you look so well!”

“I get a kind of heavy feeling. A sort of—a sort of heavy feeling. I guess I’ll put on another mile or so to my walk on my way home. So—so I’ll be back a little later from now on.”

“Very well, dear.”

It made him feel like a particularly low type of criminal; but by abandoning his daily walk he was now in a position to devote an hour a day to his lessons and still reach home in time for dinner, and Madame Gavarni had assured him that would be ample.

“Leave it to me, Bill,” she had said. She was a breezy old lady with a military mustache and an unconventional way of addressing her clientèle. “You come to me for an hour a day, and if you haven’t two left feet we’ll make a pet of Society out of you in a month. I never had a failure with a pupe yet, except once. And that wasn’t my fault.”

“Had he two left feet?”

“Hadn’t any feet at all. Fell from a roof after the second lesson and had to have ’em cut off of him. At that, I could have learned him to tango with wooden legs; but he got kind of discouraged and quit. Well, see you Monday, Bill. Be good!”

And the kindly old soul, retrieving her chewing gum from the panel of the door, where she had placed it to facilitate conversation, dismissed him.

And now began what, looking back in later years, Henry unhesitatingly considered the most miserable period of his existence. There are few times when a man who is past his first youth feels unhappier and more ridiculous than when taking a course of lessons in the modern dance. It was not so much the physical anguish of it, though everyday muscles, the existence of which he had never suspected, seemed to come into being for the sole purpose of aching. Far worse was the mental suffering.

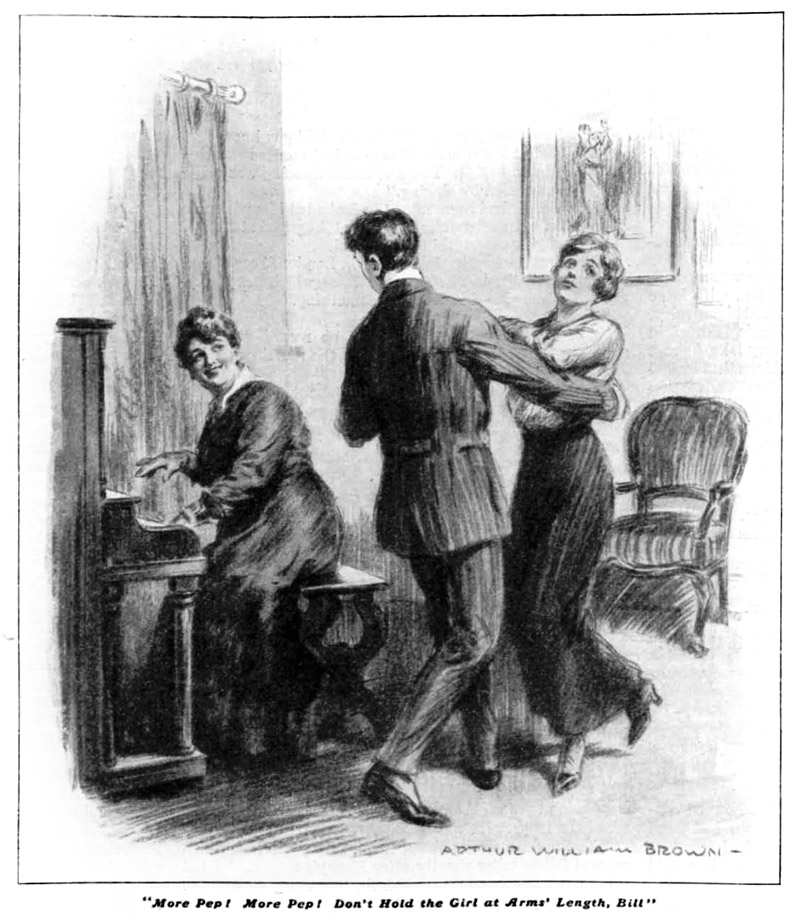

This was partly due to the peculiar method of Madame Gavarni with her pupils and partly to the fact that that lady was assisted in her tuition by her niece, a strikingly blond young lady, whose slim waist Henry could never clasp without feeling like a blackhearted traitor to his absent Minnie. Conscience racked him. Also, he had the sensation of being a strange, jointless creature, with abnormally large hands and feet. Finally, it was Madame Gavarni’s custom while playing the piano to accompany the music with spirited comments:

“More pep! More pep!”

“More pep! More pep!”

“Stick it, Vernon!”

“Don’t hold the girl at arms’ length, Bill. Hug her!” And she had a trying habit of comparing Henry’s progress with that of a certain cripple whom she claimed to have taught at some previous time. This unfortunate, though—it appeared—entirely deprived of the use of his lower limbs, had been a far superior performer to Henry. She and the niece would have lively arguments as to whether or not the cripple had one-stepped in a more agile manner after his third lesson than Henry after his fifth. The niece said no. As well, perhaps, but not better. Madame Gavarni said that the niece was forgetting the way the cripple had slid his feet. The niece said yes, that was so; maybe she was. Henry said nothing. He merely perspired.

He made progress slowly. The blame for this, however, could not fairly be laid on his instructress. Madame Gavarni’s niece did all that one woman could to speed him up. Sometimes she would even follow him into the street to show him on the sidewalk a means of doing away with one of his numerous errors of technic, the elimination of which would help to make him definitely the cripple’s superior. The misery of embracing her indoors was as nothing to the furtive guilt of clasping her in his arms on the sidewalk.

Nevertheless, having paid for his course of lessons in advance and being a determined man, he did make progress. And one day, to his surprise, he found his feet going through the motions automatically, as if they were endowed with an intelligence of their own. It was the turning point. It filled him with a pride such as he had not felt since Minnie, on the shores of the silvery lake at Ye Bonnie Brier Bush Farm, had promised to be his wife. Madame Gavarni was moved to dignified praise.

“Some speed, kid!” she observed. “Some speed!”

Henry blushed modestly. It was the accolade.

He was getting on splendidly now. The cripple’s name had dropped out of the daily conversation altogether. Every day his skill became more manifest, and every day, on reaching home, he found occasion to bless the resolve that had sent him to Madame Gavarni’s; for daily now it became more apparent to him as he watched Minnie that she was chafing at the monotony of her life. That fatal supper had wrecked the peace of their little home. Before that, her contentment had been obvious. Now it was just as obvious that she was fretting.

A blight had settled on the flat and from their relations spontaneity had departed. Little by little Minnie and he were growing almost formal toward each other. She had lost her taste for being read to in the evenings and had developed a habit of pleading a headache and going early to bed. Sometimes, catching her eye when she was not expecting it, he surprised in it an enigmatic look. It was a look, however, he was able to read. It said as plainly as the spoken word that she was bored.

It might have been expected that this state of affairs would have distressed Henry. It gave him, on the contrary, a pleasurable thrill. It made him feel that it had been worth it—going through the torments of learning to dance. If she had been contented with the life he could offer her as a nondancer, where would have been the sense of losing money and weight in order to learn the steps? The more frigid she was now, the more completely would she melt when he revealed himself. The more uncomfortable their evenings were now, the more they would appreciate their happiness later on. For Henry belonged to the school of thought which holds that there is a greater pleasure in being suddenly relieved of toothache than in never having toothache at all.

He merely chuckled inwardly, therefore, when, on the morning of her birthday, having presented her with a purse which he knew she had long coveted, he found himself thanked in a perfunctory and mechanical way.

“I’m glad you like it,” said Henry.

She looked at the purse without enthusiasm. “It’s just what I wanted,” she said listlessly.

“Well, I must be going. I’ll get the tickets for the show when I’m downtown.”

She hesitated a moment.

“I don’t believe I want to go to the theater to-night, Henry.”

“Nonsense! We must have a party on your birthday. We’ll go to the theater and then we’ll have supper at Geisenheimer’s again. I may be working after hours at the bank to-day, so I guess I won’t come home. I’ll meet you at that Italian place at six.”

“Very well. You’ll miss your walk, then?”

“Yes. It—it doesn’t matter for once.”

“No? You still go on with your walks, then?”

“Oh, yes! Yes.”

“Three miles every day?”

“Never miss it. It keeps me well.”

“Yes?”

“Good-by, darling.”

“Good-by.”

Yes, there was a distinct chill in the domestic atmosphere; but, reflected Henry, it would not last much longer now. He had rather the feeling of a young knight who has done perilous deeds for his lady and now sees the prospect at hand of cashing in on them.

Geisenheimer’s was as brilliant and noisy as it had been before when Henry reached it that night, escorting a reluctant Minnie. She had wished to abandon the idea of supper and go home, but a squad of police could not have kept Henry from Geisenheimer’s. His hour had come. He had looked forward to this moment for weeks and had visualized every detail of his big scene. They would sit down. There might be a stage wait of a few minutes. Then, infallibly, Sidney Mercer would come up and ask Minnie to dance. And then—then Henry would rise and, abandoning all concealment, exclaim grandly: “No! I am going to dance with my wife!” Stunned amazement of Minnie, changing into wild joy. Utter rout and discomfiture of that pinhead, Mercer. And then, when they had returned to their table, he breathing easily and regularly, as a trained dancer should after a little spin, she tottering a trifle with the sudden rapture of it all, they would sit with their heads together and start a new life. That was the scenario which Henry had drafted.

It worked out as smoothly as ever it had done in his dreams. They had hardly seated themselves when Sidney Mercer was beside the table, bleating greetings. Sidney had the gift, peculiar to his type, of being able to see a pretty girl come into a restaurant even when his back was toward the door.

“Henry!” he cried. “Welcome home! Our little rounder! Always here!”

“Wife’s birthday.”

“Many happy returns of the day, Mrs. Mills! We’ve just time for one turn before the waiter comes for your order. Come along!”

“No!” Henry exclaimed grandly. “I am going to dance with my wife!”

He had not overestimated the sensation the words would cause. Minnie looked at him with round eyes. Sidney Mercer was obviously startled.

“I thought you couldn’t dance?”

Henry smiled a tolerant, whimsical smile.

“You never can tell,” he said lightly. “It looks easy enough. Anyway, I’ll try.”

“Henry!” cried Minnie as he gripped her.

He had supposed she would say something like that, but hardly in that tone of voice. There is a way of saying “Henry!” which conveys surprised admiration and remorseful devotion; but she had not said it in that way. There had been a note almost of horror in her voice. He could not understand this. They were on the floor now, and it was beginning to creep on him like a chill wind that the scenario he had mapped out was subject to unforeseen alterations.

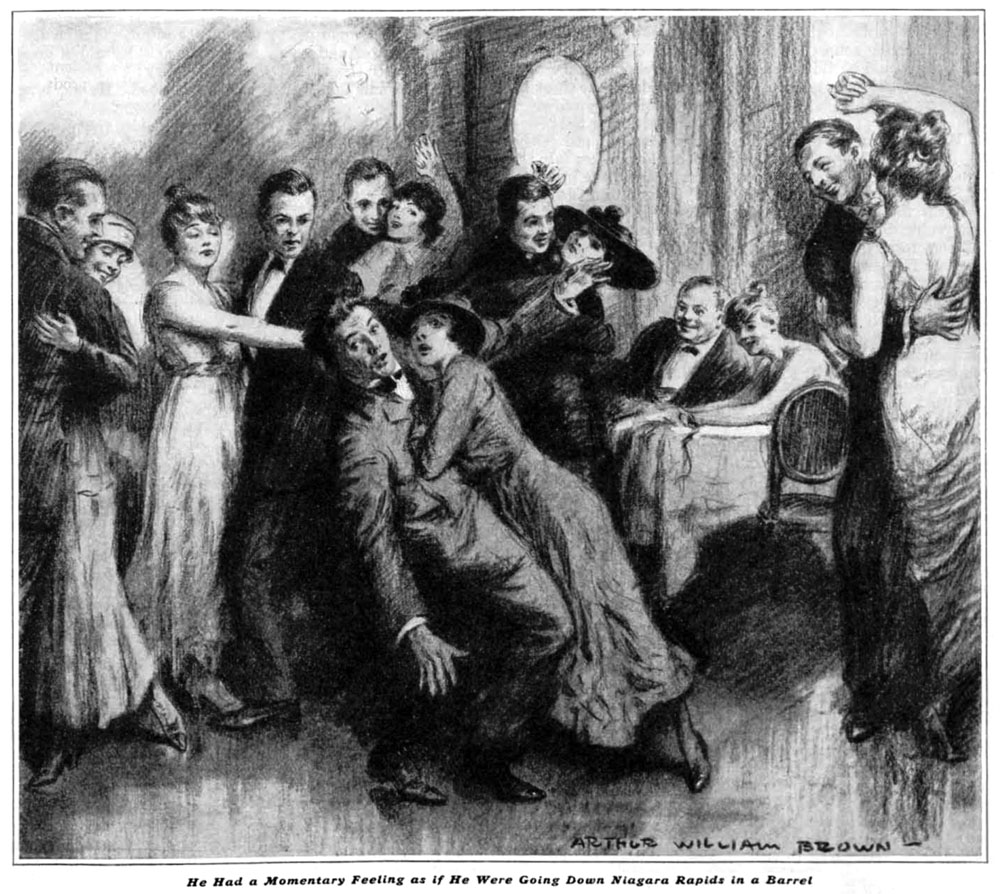

At first, all had been well. They had been almost alone on the floor and he had begun moving his feet along dotted line A-B—as recommended in The A-B-C of Modern Dancing—with a smooth confidence. And then, as if by magic, he was in the midst of a crowd—a mad, restless crowd that seemed to have no sense of direction, no ability whatever to keep out of his way. For a moment the tuition of weeks stood by him. Then, a shock, a stifled cry from Minnie, and the first collision had occurred. And with that all his painfully acquired knowledge passed from his mind.

This was a situation for which his pacings and slidings round an empty room had not prepared him. He felt unnerved and helpless. Stage fright obsessed him. Somebody charged him in the back and asked querulously where he thought he was going. Somebody else rammed him on the other side. The lights grew blurred and dizziness came on him. He had a momentary feeling as if he were going down Niagara Rapids in a barrel; and then he was lying on the floor, with Minnie on top of him. Somebody kicked him on the head.

He was aware of Sidney Mercer at his side, helping him up.

The place seemed full of demon laughter.

“Min!”

They were in the parlor of their little flat. Her back was toward him and he could not see her face. She did not answer. She preserved the silence that had lasted since they left the restaurant.

Henry’s bleak misery found vent in a torrent of words:

“I thought I could do it. Oh, Lord! I’ve been taking lessons every day since that night we first went to that place. I didn’t tell you because I wanted it to be a surprise for you on your birthday. I knew how sick and tired you were getting of being married to a man who never took you out because he couldn’t dance. I thought it was up to me to learn and give you a good time like other men’s wives have. It’s no good! I guess it’s like the old woman said: I’ve got two left feet and it’s no use my trying to fight against it. I’m sorry, Min. I did my best. I ——”

“Henry!”

She had turned, and with dull amazement he saw that her face was radiant.

“Was that why you went to that house—to take dancing lessons?” He stared at her without speaking. “So that was why you pretended you were still doing your walks! I understand now.”

“You knew!”

“I saw you come out of that house. I was just going to the Subway station at the end of the street one evening and I saw you. There was a girl with you—a girl with yellow hair. You hugged her!”

Henry licked his dry lips.

“Min,” he said huskily, “you won’t believe me, but she was trying to teach me the Jelly Roll!”

She held him by the lapels of his coat.

“Of course I believe you! I understand it all now. I thought at the time —— I can’t tell you what I thought. I almost hated you! Oh, Henry, why ever didn’t you tell me what you were doing? I know you wanted it to be a surprise for my birthday, but you must have seen there was something wrong. You must have seen that there was something the matter with me. Surely you’ve noticed how horrid I’ve been these last weeks!”

“I thought it was just that you were finding it dull.”

“Dull! Here! With you!”

Henry choked.

“It was after you danced that night with Sidney Mercer, Min. I thought the whole thing out. You’re so much younger than me, Min. It—it didn’t seem right for a wonderful girl like you to have to be cooped up for the rest of your life, being read to by a fellow like me.”

“But I loved it!”

“I knew you were missing your dancing. You’ve got to dance. Every girl has to. Women can’t do without it.”

She threw her head back, laughing.

“This one can, Henry. Listen! You remember how ill and worn-out I was when you first met me at the farm? Do you know how I came to be like that? It was because I had been slaving away for years at one of those dance-hall places, where you go in and pay five cents for a dance with one of the lady instructresses.

“I was one of the lady instructresses, Henry. You can’t begin to imagine what I went through. Day after day a million heavy men with large feet —— I tell you, you are a professional compared with some of them! They trod on my feet and leaned their two hundred pounds on me and nearly killed me. Now perhaps you can understand why I’m not crazy about dancing, though I know I dance well. Believe me, Henry, the kindest thing you can do to me is to forbid me ever to dance again!”

“You! You ——” He gulped. “Do you really mean that you can stand—that you can be satisfied with the sort of life we’re living? You won’t really find it dull?”

“Dull!”

She ran to the bookshelf and came back with a large volume.

“Read to me, Henry, dear. Read me something now. It seems ages and ages since you used to. Read me something out of the Encyclopædia!”

Henry was looking at the book in his hand. In the midst of a joy that almost overwhelmed him his orderly mind was conscious of something wrong.

“But this is the Med-Mum volume, darling!”

“Is it? I didn’t look. Well, that’ll do. Read me all about Mum.”

“But we’re only in the Cal-Cha!”

He wavered. Then something of recklessness came into his manner. He gave a careless, happy laugh.

“All right! I don’t care! I will, by George!”

“Sit right down here, dear, and I’ll sit on the floor.” Henry cleared his throat.

“ ‘Milicz, or Militsch (d. 1374), Bohemian divine, was the most influential among those preachers and writers in Moravia and Bohemia who, during the fourteenth century, in a certain sense paved the way for the reforming activity of Huss.’ ”

His voice died away. He looked down. Minnie’s soft hair was resting against his knee. He put out a hand and stroked it. She turned and looked up—and he met her big eyes.

“Can you beat it!” said Henry silently to himself.

Editor’s note:

The opening paragraph slightly misquotes an 1890 song by M. F. Carey (sheet music at this link). The original lyric is:

Clarence McFadden he wanted to waltz,

But his feet wasn’t gaited that way.

So he saw a professor and stated his case

And said he was willing to pay.

The professor looked down in alarm at his feet

As he viewed their enormous expanse,

And he tacked on a five to his regular price

For learning McFadden to dance.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums