The Strand Magazine, January 1913

HAVE always admired the “Synopsis of Preceding Chapters” which

tops each instalment of a serial in a daily paper. It is so curt, so

compelling. It takes you by the scruff of the neck and hurls you

into the middle of the story before you have time to remember that

what you were really intending to read was “How to Make a Dainty

Winter Coat for Baby Out of Father’s Motor-Goggles” on the next

page. I can hardly, I think, do better than adopt the same method in

serving up the present narrative.

HAVE always admired the “Synopsis of Preceding Chapters” which

tops each instalment of a serial in a daily paper. It is so curt, so

compelling. It takes you by the scruff of the neck and hurls you

into the middle of the story before you have time to remember that

what you were really intending to read was “How to Make a Dainty

Winter Coat for Baby Out of Father’s Motor-Goggles” on the next

page. I can hardly, I think, do better than adopt the same method in

serving up the present narrative.

As follows:—

BEGIN TO-DAY.

Lord Freddie Bowen, visiting New York, has met, fallen in love with, proposed to, and been accepted by

Margaret, daughter of

Franklyn Bivatt, an unpleasant little millionaire with a weak digestion, a taste for dogmatic speech, and a personal appearance rather like one of Conan Doyle’s pterodactyls. Lord Freddie has called on Mr. Bivatt, told him the news, and asked for his consent.

NOW GO ON WITH THE STORY.

Mr. Bivatt looked at Lord Freddie in silence. He belonged to the second and more offensive class of American millionaire. There are only two kinds. One has a mauve face and an eighteen-stone body, and grinds the face of the poor on a diet of champagne and lobster à la Newburg; the other—Mr. Bivatt’s type—is small and shrivelled, weighs seven stone four, and fortifies himself, before clubbing the stuffing out of the widow and the orphan, with a light repast of hot water, triturated biscuit, and pepsine tabloids.

Lord Freddie also looked at Mr. Bivatt in silence. It was hard to believe that this curious little being could be the father of a girl who did not look really repulsive even in a photograph in a New York Sunday paper.

Mr. Bivatt broke the silence by taking a pepsine tabloid. Before speaking he took another look at Freddie—a thoroughly nasty look. The fact was that Freddie had chosen an unfortunate moment for his visit. Not only had Mr. Bivatt a bad attack of indigestion, but he had received that very morning from Margaret’s elder sister, who some two years before had married the Earl of Datchet, a letter which would have prejudiced the editor of “Debrett” against the British Peerage. Lord Datchet was not an ideal husband. Among other things, he was practically a lunatic, which is always such a nuisance in the home. This letter was the latest of a number of despatches from the seat of war, and the series, taken as a whole, had done much to diminish Mr. Bivatt’s simple faith in Norman blood. One titled son-in-law struck him as sufficient. He was not bitten by a craze for becoming a collector.

Consequently he looked at Lord Freddie and said “H’m!”

Freddie was somewhat disturbed. In the circumstances “H’m!” was scarcely an encouraging remark.

“You mean——?” he said.

“I mean just this. When Margaret marries she’s going to marry a real person, not”—his mind wandered to the absent Datchet—“not a pop-eyed, spindle-shanked jack-rabbit, all nose and front teeth and eyeglass, with hair the colour of butter, and no chin or forehead. See?”

Freddie started, and his eye moved hastily to the mirror over the mantelpiece. What he saw partly reassured him. True, he was no Apollo. He was square and bullet-headed, and his nose had never really been the same since he had ducked into instead of away from the Cambridge light-weight’s right swing in the inter-’Varsity competition; but apart from that he attained a pretty fair standard. Chin? If anything, he had too much. Teeth? Not at all prominent. Hair? Light, certainly; at school he had been called “Ginger.” But what of that? No, the description puzzled him.

“Am I a jack-rabbit?” he inquired, curiously.

“I don’t know,” said Mr. Bivatt. “I don’t know anything about you. I’ve never heard your name before. I’ve forgotten it now. What is your name? I only know it’s got a ‘Lord’ tacked on to it.”

“By Nature. Not by me. It runs in the blood. Don’t you like lords?”

Mr. Bivatt eyed him fixedly and swallowed another tabloid. “Do you know the Earl of Datchet?” he asked.

“Only by reputation.”

“Oh, you do know him by reputation? What have you heard about him?”

“Well, only in a general way that he’s a pretty average sort of rotter. A bit off his chump, I’ve heard. One of the filberts, don’t you know, and all that sort of thing. Nothing more.”

“You didn’t hear that he was my son-in-law? Well, he is. So now perhaps you understand why I didn’t leap at you and fold you in my arms when you suggested marrying Margaret. I don’t want another Datchet in the family.”

“Good Lord! I hope I’m not like Datchet!”

“I hope you’re not, for your sake, if you want to marry Margaret. Well, let’s get down to it. Datchet’s speciality was aristocratic idleness. He had never done a day’s work in his life. No Datchet ever had, apparently. The last time any of the bunch had ever shown any signs of perspiring at the brow was when the first Earl carried William the Conqueror’s bag down the gangway. Is that your long suit, too—trembling when you see a job of work? How old are you? Twenty-seven? Well, keep it to the last six years, if you like. What have you done since you came of age?”

“Well, I suppose if you put it that way——”

“I do put it just that way. Have you earned a cent in your life?”

“No. But——”

“It isn’t a case of but. I know exactly what you’re trying to say, that there wasn’t any need for you to work, and so on. I know all that. That’s not the point. The point is that the man who marries Margaret has got to be capable of work. There’s only one way of telling the difference between a man and a jack-rabbit till you get to know them, and that is that the man will work.” Mr. Bivatt took another tabloid. “You remember Jacob?” he said.

“Jacob? I’ve met a man called Jacob at the National Sporting Club.”

“I mean the one in the Bible, the one who worked seven years for the girl, got the wrong one, and started in right away to do another seven years. He wasn’t a jack-rabbit!”

“Wonderful Johnny,” agreed Lord Freddie, admiringly.

“They managed things mighty sensibly in those days. You didn’t catch them getting stung by any pop-eyed Datchets. It’s given me an idea, talking of Jacob. That’s the sort of man I want for Margaret. See? I don’t ask him to wait seven years, let alone fourteen. But I will have him show that there’s something in him. Now, I’ll make a proposition to you. You go and hunt for a job and get it, and hold it long enough to make five hundred dollars, and you can marry Margaret as soon as you like afterwards. But you’ve got to make it by work. No going out and winning it at poker, or putting your month’s allowance on something to win and for a place. See?”

“It seems to me,” said Freddie, “that you bar every avenue of legitimate enterprise. But I shall romp home all the same. You mean earn five hundred, not save it?”

“Earn will do. But let’s get this fixed right. When I say earn, I mean earn. I don’t mean sit up and beg and have it fall into your mouth. Manual work or brain work it’s got to be—one of the two. I shall check your statement pretty sharply. And you’ll drop your title while you’re at it. You’ve got to get this job on your merits, if you have any. Is that plain?”

“Offensively.”

“You mean to try it? You won’t like it.”

“I don’t suppose Jacob liked it—what?”

“I suppose not. Good morning.”

And Mr. Bivatt, swallowing another tabloid, turned his attention once more to harrying the widow and the orphan.

Freddie, when he set out on his pilgrimage, had his eyes open for something soft and easy. But there are no really easy jobs. Even the man who fastened a snake into a length of hose-pipe with a washer, and stood in the background working a police-rattle—the whole outfit being presented to the public in a dim light as the largest rattlesnake in captivity—had to run for his life when the washer worked loose and the snake escaped.

It amazed Freddie, the difficulty of getting work. Work had always seemed to him so peculiarly unpleasant that he had supposed that the supply must exceed the demand. The contrary appeared to be the case.

Eventually, after wearing a groove in the pavements, he found himself, through a combination of lucky chances, in charge of the news-stand at a large hotel. Twelve dollars a week was the stipend. Working it out on a slip of paper, he perceived that his ordeal was to be a mere few months’ canter of unexacting work in quite comfortable surroundings. Datchet himself could have done it on his butter-coloured head.

There is always a catch in these good things. For four days all went well. He found his duties pleasant. But on the fifth day came reaction. From the moment he began work a feeling of utter loathing for this particular form of money-making enveloped him as in a cloud. The customers irritated him. He was hopelessly bored.

The end was in sight. It came early on the afternoon of the sixth day, through the medium of one of the regular customers, a man who, even in happier moments, had always got on his nerves. He was a man with a rasping voice and a peremptory manner, who demanded a daily paper or a penny stamp with the air of one cursing an enemy.

Freddie had fallen into gloomy meditation, business being slack at the time, when this man appeared before him and shouted:—

“Stamp!”

Freddie started, but made no reply.

“Stamp!”

Freddie’s gaze circled round the lobby and eventually rested on the object before him.

“Stamp!”

Freddie inspected him with frigid scorn.

“Why should I?” he asked, coldly.

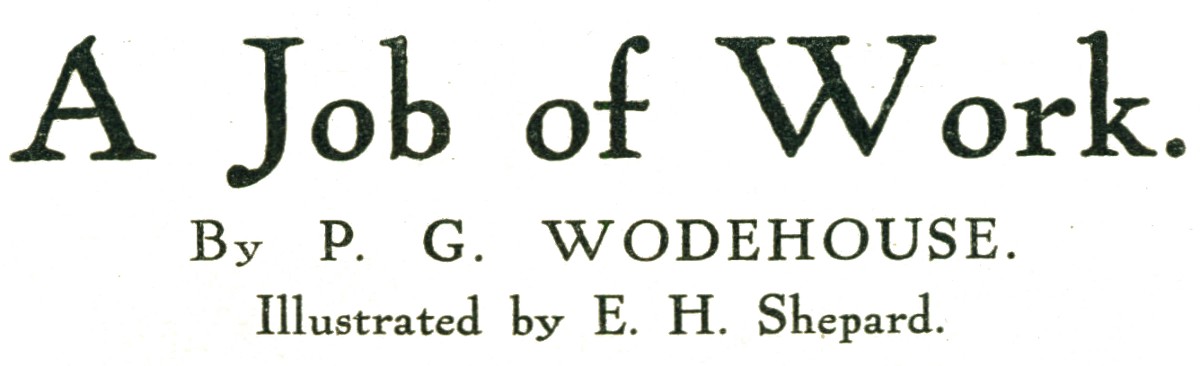

The hotel in which Freddie had found employment was a sporting hotel in the heart of that section of New York known as the Tenderloin. Its patrons were mainly racing men, gamblers, and commercial travellers, men of action rather than words. This particular patron was essentially the man of action. Freddie’s question offending him, he hit him in the eye, and a minute later Freddie, breathing slaughter, had vaulted the barrier of newspapers, and the battle was raging all over the lobby, to the huge contentment of a mixed assortment of patrons, bell-boys, bar-keepers, pages, and waiters from the adjoining café. Six minutes later, when Freddie, panting a little and blinking to ease the pain of his injured eye, was waiting for his opponent to rise, which he did not do, the manager entered the arena. The manager was a man with sporting blood and a sense of the proprieties. The former had kept him an interested spectator during the late proceedings; the latter now made him step forward, tap Freddie on the shoulder, and inform him that his connection with the hotel was at an end.

Freddie went out into the world with twelve dollars and a black eye. As he passed through the swing door a slight cheer was raised in his honour by the grateful audience.

I would enlarge on Freddie’s emotions at losing his situation, were it not for the fact that two days later he found another. There was a bell-boy at his late hotel to whom he had endeared himself by allowing him to read the baseball news free of charge; a red-headed, world-weary, prematurely aged boy, to whom New York was an open book. He met Freddie in the street.

“Halloa, you!” he said. “I been huntin’ after you. Lookin’ fer a job? My cousin runs a café on Fourteenth Street. He’s wantin’ a new waiter. I seen the card in the window yesterday. You try there and say I sent you. It’s a tough joint, though.”

“After what happened the day before yesterday, it seems to me that the tougher the joint the more likely I am to hold my job. I seem to lack polish.”

“The East Side Delmonico’s is the name.”

“It sounds too refined for me.”

“It may sound that way,” said the bell-boy, “but it ain’t.”

Nor was it. The East Side Delmonico’s proved to be a dingy though sizable establishment at a spot where Fourteenth Street wore a more than usually tough and battered look. Fourteenth Street has that air of raffish melancholy which always marks a district visited for awhile and then deserted by fashion.

It appeared that the bell-boy, who had been clearly impressed by Freddie’s handling of the irritable news-stand customer, had given him an excellent character in advance; and he found, on arrival, that he was no stranger to Mr. “Blinky” Anderson, the proprietor. The bell-boy’s cousin welcomed him, if not with open arms, with quite marked satisfaction. He examined the injured eye, stamped it with the seal of his approval as “some lamp,” and, having informed him that his weekly envelope would contain five dollars and that his food was presented free by the management, requested him to slip out of his coat, grab an apron, and get busy.

Freddie was a young man who took life as it came. He was a sociable being, and could be happy anywhere so long as he was not bored. The solitude of the news-stand had bored him, but at the East Side Delmonico’s life was too full of movement to permit of ennui. He soon perceived that there was more in this curious establishment than met the eye, and this by design rather than accident. The fact was that “Blinky’s,” as its patrons tersely styled Anderson’s Parisian Café and Restaurant, the East Side Delmonico’s, offered attractions to the cognoscenti other than the mere restoration of the inner man with meat and drink. On the first floor, for instance, provided that you could convince the management of the excellence of your motives, you could “buck the tiger”—a feat which sounds perilous but is not, except to the purse. On the floor above, again, if you were that kind of idiot, you might play roulette. And in the basement, in a large, cellar-like room, lit with countless electric lights, boxing contests were held on Saturday nights before audiences financially, if not morally, select.

In fact, the East Side Delmonico’s was nothing more nor less than a den of iniquity. But nobody could call it dull, and Freddie revelled in his duties. He booked orders, served drinks, smashed plates, bullied the cook, chaffed the customers when they were merry, seized them by the neck and ran them into the street when they were too merry, and in every other way comported himself like one who has at last found his true vocation. And time rolled on.

We will leave time rolling for the moment and return to Mr. Bivatt, raising the curtain at the beginning of his tête-à-tête dinner with his fellow-plutocrat, T. Mortimer Dunlop. T. Mortimer was the other sort of millionaire. You could have told he was a millionaire just by looking at him. He bulged. Wherever a man can bulge, there did T. Mortimer Dunlop bulge. His head was bald, his face purple, his hands red. He was accustomed to refer to himself somewhat frequently as a “dead game sport.” He wheezed when he spoke.

I raise the curtain on Mr. Bivatt at the beginning of dinner because it was at the beginning of dinner that he allowed Mr. Dunlop to persuade him to drink a Dawn of Hope cocktail—so called because it cheers you up. It cheered Mr. Bivatt up.

Mr. Bivatt needed cheering up. That very afternoon his only son Twombley had struck him for a thousand dollars to pay a poker debt. A thousand dollars is not a large sum to a man of Mr. Bivatt’s wealth, but it is your really rich man who unbelts least joyously. Together with the cheque Twombley had received a parental lecture. He had appeared to be impressed by it; but it was the doubt as to its perfect efficacy which was depressing Mr. Bivatt. There was no doubt that Twombley was a trial. It was only the awe with which he regarded his father that kept him within bounds. Mr. Bivatt sighed and took a pepsine tabloid.

It was at this point that T. Mortimer Dunlop, summoning the waiter, ordered two Dawn of Hope cocktails.

“Nonsense!” he wheezed, in response to Mr. Bivatt’s protest. “Be a sport! I’m a dead game sport. Hurry up, waiter. Two Dawn of Hope.”

Mr. Bivatt weakly surrendered. He was there entirely to please Mr. Dunlop, for there was a big deal in the air, to which Mr. Dunlop’s co-operation was essential. This was no time to think about one’s digestion or the habits of a lifetime. If, to conciliate invaluable Mr. Dunlop, it was necessary to be a dead game sport and drink a cocktail, then a dead game sport he would be. He took the curious substance from the waiter and pecked at it like a nervous bird. He blinked, and pecked again—less nervously this time.

You, gentle reader, who simply wallow in alcoholic stimulants at every meal, will find it hard to understand the wave of emotion which surged through Mr. Bivatt’s soul as he reached the half-way point in the magic glass. But Mr. Bivatt for thirty years had confined his potions to hot water, and the effect on him was remarkable. He no longer felt depressed. Hope, so to speak, had dawned with a jerk. Life was a thing of wonderful joy and infinite possibilities.

We therefore find him, at the end of dinner, leaning across the table, thumping it with clenched fist, and addressing Mr. Dunlop through the smoke of the latter’s cigar thus:—

“Dunlop, old man, how would it be to go and see a show? I’m ready for anything, old man, Dunlop. I’m a dead game sport, Dunlop, old fellow! That’s what I am.”

One thing leads to another. The curtain falls on Mr. Bivatt smoking a Turkish cigarette in a manner that can only be described as absolutely reckless.

These things, I should mention, happened on a Saturday night. About an hour after Mr. Bivatt had lit his cigarette Freddie, in the café at the East Side Delmonico’s, was aware of a thick-set, short-haired, tough-looking young man settling himself at one of the tables and hammering a glass with the blade of his knife. In the other hand he waved the bill of fare. He was also shouting, “Hey!” Taking him for all in all, Freddie set him down as a hungry young man. He moved towards him to minister to his needs.

“Well, cully,” he said, affably, “and what will you wrap yourself around?”

You were supposed to unbend and be chummy with the customers if you were a waiter at “Blinky’s.” The customers expected it. If you called a patron of the East Side Delmonico’s “sir,” he scented sarcasm, and was apt to throw things.

The young man had a grievance.

“Say, can you beat it? Me signed up to fight a guy here at a hundred and thirty-three, ring-side, and starving meself for weeks to make the weight. Say, I ain’t had a square meal since Ponto was a pup—and gee! along comes word that he’s sprained a foot and will we kindly not expect him. And all I get is the forfeit money.”

He snorted.

“Forfeit money! Keep it! It ain’t but a hundred plunks, and the loser’s end was three hundred. And there wouldn’t have been any loser’s end in mine at that. Why say, I’d have licked that guy with me eyes shut.”

He kicked the table-leg morosely.

“Your story moves me much,” said Freddie. “And now, what shall we shoot into you?”

“You attending to this table?”

“I am.”

The young man scanned the bill of fare.

“Noodle-soup-bit-o’-weakfish-fried-chicken-Southern-style- corn-on-the-cob-bit-o’steak-fried-potatoes-four-fried-eggs-done-on-both-sides-apple-dumpling-with-hard-sauce-and-a-cup-of-custard,” he observed rapidly. “That’ll do to start with. And, say, bring all the lager-beer you can find. I’ve forgotten what it tastes like.”

“That’s right,” said Freddie, sympathetically; “keep your strength up.”

“I’ll try,” said the thick-set young man. “Get a move on.”

There was no doubt about the pugilist’s appetite. It gave Freddie quite a thrill of altruistic pleasure to watch him eat. He felt like a philanthropist entertaining a starving beggar. He fetched and carried assiduously for the diner, and when at length the latter called for coffee and a cigar and sank back in his chair with a happy sigh, he nearly cheered.

On his way to the kitchen he encountered his employer, Mr. “Blinky” Anderson, looking depressed. Freddie gathered the reason for his gloom. He liked “Blinky,” and thought respectful condolence would not be out of place.

“Sorry to hear the news, sir.”

“Hey?” said Mr. Anderson, moodily.

“I hear the main event has fallen through.”

“Who told you?”

“I have been waiting on one of the fighters upstairs.”

Mr. Anderson nodded.

“That would be the Tennessee Bear-Cat.”

“Very possibly. He had that appearance.”

Like the Bear-Cat, Mr. Anderson was rendered communicative by grief. Freddie had a sympathetic manner, and many men had confided in him.

“It was One-Round Smith who backed down. Says he’s hurt his foot. Huh!” Mr. Anderson grunted satirically, but pathos succeeded satire again almost at once. “I ain’t told them about it yet,” he went on, jerking his head in the direction of the invisible audience. “The preliminaries have just started, and what those guys will say when they find there ain’t going to be a main event I don’t know. I guess they’ll want to lynch somebody. I ought to tell ’em right away but I can’t seem to sorter brace myself to it. It’s the best audience, too, we’ve ever had. All the sports in town are there. Rich guys, too—none of your cheap skates. I just seen old man Dunlop blow in with a pal, and he’s worth all sorts o’ money. And now there won’t be no fight. Wouldn’t that jar you?”

“Can’t you find a substitute?”

“Substitute! This ain’t a preliminary between two dubs. It was the real thing for big money. And all the sports in town come to watch it. Substitute! Ain’t you ever heard of the Bear-Cat? He’s a wild Indian. Who’s going to offer to step up and swap punches with a terror like him?”

“I am,” said Freddie.

Mr. Anderson stared at him with open mouth.

“You!”

“Me.”

“You’ll fight the Tennessee Bear-Cat?”

“I’d fight Jack Johnson if he’d just finished the meal that fellow has been having,” said Freddie, simply.

Mr. Anderson was not a swift thinker. He stood, blinking, and allowed the idea to soak through. It penetrated slowly, like water through a ceiling.

“He’d eat you,” he said, at last.

“Well, I’m the only thing in this place he hasn’t eaten. Why stint him?”

“But, say, have you done any fighting?”

“As an amateur, a good deal.”

“Amateur! Say, can you see them sports down there standing a main event between the Tennessee Bear-Cat and an amateur?”

“Why tell them? Say I’m the heavy-light-weight champion of England.”

“What’s a heavy-light-weight?”

“It’s a new class, in between the lights and the welters.”

By this time the idea had fairly worked its way through into Mr. Anderson’s mind, and its merits were beginning to appeal to him. It was certain that, if Freddie were not allowed to fill the gap, there would be no main event that night. And in the peculiar circumstances it was just possible that he might do well enough to satisfy the audience. The cloud passed from Mr. Anderson’s face, for all the world as if he had taken a Dawn of Hope cocktail.

“Why, say,” he said, “there’s something in this.”

“You bet there is,” said Freddie. “There’s the loser’s end, three hundred of the best.”

Mr. Anderson clapped him on the shoulder.

“And another hundred from me if you last five rounds,” he said. “I guess five’ll satisfy them, if you make them fast ones. I’ll go and tell the Bear-Cat.”

“And I’ll go and get him his coffee and the strongest cigar you keep. Every little helps.”

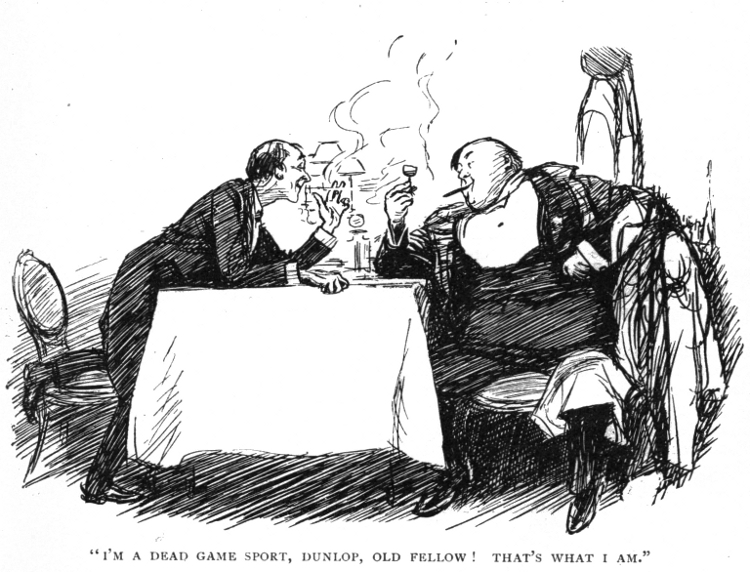

Freddie entered the ring in a costume borrowed from one of the fighters in the preliminaries, and, seating himself in his corner, had his first sight of Mr. “Blinky” Anderson’s celebrated basement. Most of the light in the place was concentrated over the roped platform of the ring, and all he got was a vague impression of space. There seemed to be a great many people present. The white shirt-fronts reminded him of the National Sporting Club.

His eye was caught by a face in the first row of ring-side seats. It seemed familiar. Where had he seen it before? And then he recognized Mr. Bivatt—a transformed Mr. Bivatt, happier-looking, excited, altogether more human. Their eyes met, but there was no recognition in the millionaire’s. Freddie had shaved his moustache as a preliminary to the life of toil, and Mr. Bivatt, beaming happily up at him from beside that dead game sport, T. Mortimer Dunlop, had no recollection of ever having seen him before.

Freddie’s attention was diverted from audience to ring by the

arrival of the Tennessee Bear-Cat. There was a subdued murmur of

applause—applause had to be merely murmured on these occasions—and

for one moment, as he looked at him, Freddie regretted the contract

he had undertaken. What Mr. Anderson had said about wild Indians came

home to him. Certainly the Bear-Cat looked one. He was an

extraordinarily-muscled young man. Freddie was mainly muscle

himself, but the Bear-Cat appeared to be a kind of freak. Lumps and

cords protruded from him in all directions. His face wore a look of

placid content, and he had a general air of happy repletion, a

fate-cannot-touch-me-I-have

A shirt-sleeved gentleman of full habit climbed into the ring, puffing slightly.

“Gents! Main event. Have an apology offer—behalf of the management. Was to have been ten-round between Sam Proctor, better known as th’ Tennessee Bear-Cat, and One-Round Smith, at one-thirty-three ring-side. But—seems to have been a—naccident. One-Round havin’ sustained severe injury to foot. Rend’rin’ it—impossible—appear t’night before you. Deeply regret unavoid’ble dis’pointment.”

The portly man’s breath was going fast, but he still had sufficient for a brilliant flight of fancy, a vast improvement on Freddie’s humble effort.

“Have honour, however, present t’you Jimmy Smith, brother of One-Round—stranger to this city—but—well known on Pacific Coast—where—winner of forty-seven battles. Claimant to welter-weight belt. Gents, Jimmy Smith, the Santa Barbara Whirlwind!”

Freddie bowed. The speech, for some mysterious reason probably explainable by Christian Science, had had quite a tonic effect on him. The mere thought of those forty-seven victories gave him heart. After all, who was this Tennessee Bear-Cat? A mere walking repository of noodle soup, weakfish, fried chicken, eggs, corn, apple-dumplings, lager-beer, and cup-custards. A perambulating bill of fare. That was what he was. And, anyway, he was probably muscle-bound, and would be as slow as a top.

The introducer, however, presented him in another aspect. He had got his second wind now, and used it.

“Gents! The Tennessee Bear-Cat! You all know Sam. The toughest, huskiest, wickedest little old slugger that ever came down the pike. The boy who’s cleaned up all the light-weights around these parts, and is in a dead straight line—for—the champeenship of the world.”

He waved his hand dramatically. The Bear-Cat, overwhelmed by these tributes, shifted his chewing-gum to the other cheek, and simpered coyly, as who should say, “Stop your nonsense, Archibald!” And the gong clanged.

Freddie started the fight with the advantage that his plan of campaign was perfectly clear in his mind. Rapid attack was his policy. When a stout gentleman in shirt-sleeves has been exhausting his scanty stock of breath calling you a whirlwind, decency forbids that you should behave like a zephyr. He shook hands, and, on the principle of beginning as you mean to go on, proceeded without delay to poke his left earnestly into the middle of the Bear-Cat’s face. He then brought his right round with a thud on to what the latter probably still called his ear—a strange, shapeless growth rather like a leather cauliflower—and sprang back. The Bear-Cat shifted his gum and smiled gratefully.

A heavy swing on the part of the Bear-Cat was the next event of note. Freddie avoided it with ease and slipped in a crisp left. As he had expected, his opponent was too slow to be dangerous. Dangerous! He was not even making the thing interesting, thought Freddie as he side-stepped another swing and brought his right up to the chin. He went to his corner at the end of the round, glowing with satisfaction. This was easy.

It was towards the middle of the second round that he received a shock. Till then the curious ease with which he had reached his opponent’s head had caused him to concentrate on it. It now occurred to him that by omitting to attack the body he was, as it were, wasting the gifts of Providence. Consequently, having worked his man into an angle of the ropes with his back against a post, he feinted with his left, drew a blow, and then, ducking quickly, put all his weight into a low, straight right.

The effect was remarkable. The Bear-Cat uttered a startled grunt; a look came into his face of mingled pain and reproach, as if his faith in human nature had been shaken, and he fell into a clinch. And as Freddie vainly struggled to free himself a voice murmured in his ear:—

“Say, cut that out!”

The stout referee prised them apart. Freddie darted forward, missed with his left, and the Bear-Cat clinched again—more, it appeared, in order to resume the interrupted conversation than from motives of safety.

“Leave me stummick be, you rummy,” he hissed, rapidly. “Ain’t you got no tact? ‘Blinky’ promised me fifty if I’d let you stay three rounds, but one more like that, and I’ll forget meself and knock you through the ceiling.”

Only when he reached his corner did the full meaning of the words strike Freddie. All the glow of victory left him. It was a put-up job! “Blinky,” to ensure his patrons something resembling a fight, had induced the Bear-Cat to fight false during the first three rounds.

The shock of it utterly disheartened him. So that was why he had been making such a showing! That was why his jabs and hooks had got home with such clockwork precision! Probably his opponent had been laughing at him all the time. The thought stung him. He had never been remarkable for an even temper, and now a cold fury seized him. He would show them, by George!

The third round was the most spectacular of the fight. Even the regular patrons of “Blinky’s” Saturday night exhibitions threw aside their prudence and bellowed approval. Smiling wanly and clinching often, the Bear-Cat fixed his mind on his fifty dollars to buoy himself up, while Freddie, with a nasty gleam in his eyes, behaved every moment more like a Santa Barbara Whirlwind might reasonably be expected to behave. Seldom had the Bear-Cat heard sweeter music than the note of the gong terminating the round. He moved slowly to his corner, and handed his chewing-gum to his second to hold for him. It was strictly business now. He thought hard thoughts as he lay back in his chair.

In the other corner Freddie also was thinking. The exhilarating exercise of the last round had soothed him and cleared his brain; and he, too, as he left his corner for the fourth session, was resolved to attend strictly to business. And his business was to stay five rounds and earn that hundred dollars.

Connoisseurs in the ring-seats, who had been telling their friends during the previous interval that Freddie had “got him going,” changed their minds and gave it as their opinion that he had “blown up.” They were wrong. He was fighting solely on the defensive now from policy, not from fatigue.

The Bear-Cat came on with a rush, head down, swinging with left and right. The change from his former attitude was remarkable, and Freddie, if he had not been prepared for it, might have been destroyed offhand. There was no standing up against such an onslaught. He covered up and ducked and slipped and side-stepped, and slipped again, and, when the gong sounded, he was still intact.

Freddie came up for the fifth round brimming over with determination. He meant to do or die. Before the end of the first half-minute it was borne in upon him that he was far more likely to die than do. He was a good amateur boxer. He had been well taught, and he knew all the recognized stops for the recognized blows. But the Bear-Cat had either invented a number of blows not in the regular curriculum, or else it was his manner of delivering them that gave that impression. Reason told Freddie that his opponent was not swinging left and right simultaneously, but the hard fact remained that, just as he guarded one blow, another came from the opposite point of the compass and took him squarely on the side of the head. He had a disagreeable sensation as if an automobile had run into him, and then he was on the floor, with the stout referee sawing the air above him.

The thought of a hundred dollars is a reviving agent that makes oxygen look like a sleeping-draught. No sooner had it returned to his mind than his head cleared and he rose to his feet, as full of fight as ever. He perceived the Bear-Cat slithering towards him, and leaped to one side like a Russian dancer. The Bear-Cat collided with the ropes and grunted discontentedly.

Probably if Freddie had had a sizable plot of ground, such as Hyde Park or Dartmoor, to manœuvre in, he might have avoided his opponent for some considerable time. The ring being only twenty feet square, he was hampered. A few more wild leaps, interspersed with one or two harmless left jabs, and he found himself penned up in a corner, with the Bear-Cat, smiling pleasantly again now, making hypnotic passes before his eyes.

The Bear-Cat was not one of your reticent fighters. He was candour itself.

“Here it comes, kid!” he remarked, affably, and “it” came. Freddie’s world suddenly resolved itself into a confused jumble of pirouetting stars, chairs, shirt-fronts, and electric lights, and he fell forward in a boneless heap. There was a noise of rushing waters in his ears, and, mingled with it, the sound of voices. Some person or persons, he felt dimly, seemed to be making a good deal of an uproar. His brain was clouded, but the fighting instinct still worked within him; and, almost unconsciously, he groped for the lower rope, found it, and pulled himself to his feet. And then the lights went out.

How long it was before he realized that the lights actually had gone out, and that the abrupt darkness was not due to a repetition of “it,” he never knew. But it must have been some length of time, for when the room became suddenly light again his head was clear and, except for a conviction that his neck was broken, he felt tolerably well.

His eyes having grown accustomed to the light, he saw with astonishment that remarkable changes had taken place in the room. With the exception of some half-dozen persons, the audience had disappeared entirely, and each of those who remained was in the grasp of a massive policeman. Two more intelligent officers were beckoning to him to come down from the platform.

The New York police force is subject to periodical attacks of sensitiveness with regard to the purity of the city. In between these spasms a certain lethargy seems to grip it, but when it does act its energy is wonderful. The East Side Delmonico’s had been raided.

It was obvious that the purity of the city demanded that Freddie should appear in court in a less exiguous costume than his present one. The two policemen accompanied him to the dressing-room.

On a chair in one corner sat the Tennessee Bear-Cat, lacing his shoes. On a chair in another corner sat Mr. Franklyn Bivatt, holding his head in his hands.

Fate, Mr. Bivatt considered, had not treated him well. Nor, he added mentally, had T. Mortimer Dunlop. For directly the person, to be found in every gathering, who mysteriously gets to know things in advance of his fellows had given the alarm, T. Mortimer, who knew every inch of “Blinky’s” basement and, like other dead game sports who frequented it, had his exits and his entrances—particularly his exits—had skimmed away like a corpulent snipe and vanished, leaving Mr. Bivatt to look after himself. As Mr. Bivatt had failed to look after himself, the constabulary were looking after him.

“Who’s the squirt?” asked the first policeman, indicating Mr. Bivatt.

“I don’t know,” said the second. “I caught him trying to hook it, and held him. Keep an eye on him. I think it’s Boston Willie, the safe-blower. Keep these three here till I get back. I’m off upstairs.”

The door closed behind them. Presently it creaked and was still. The remaining policeman was leaning against it.

The Tennessee Bear-Cat nodded amiably at Freddie.

“Feeling better, kid? Why didn’t you duck? I told you it was coming, didn’t I?”

Mr. Bivatt groaned hollowly. Life was very grey. He was in the hands of the police, and he had indigestion and no pepsine tabloids.

“Say, it ain’t so bad as all that,” said the Bear-Cat. “Not if you’ve got any sugar, it ain’t.”

“My doctor expressly forbids me sugar,” replied Mr. Bivatt.

The Bear-Cat gave a peculiar jerk of his head, indicative of the intelligent man’s contempt for the slower-witted.

“Not that sort of sugar, you rummy. Gee! Do you think this is a tea-party? Dough, you mutt.”

“Do you mean money, by any chance?” asked Freddie.

The Bear-Cat said that he did mean money. He went further. Mr. Bivatt appearing to be in a sort of trance, he put a hand in his pocket and extracted a pocket-book.

“I guess these’ll do,” he said, removing a couple of bills.

He rapped on the door.

“Hey, Mike!”

“Quit that,” answered a gruff voice without.

“I want to speak to you. Got something to say.”

The door opened.

“Well?”

“Say, Mike, you’ve got a kind face. Going to let us go, ain’t you?”

The policeman eyed the Bear-Cat stolidly. The Bear-Cat’s answering glance was more friendly.

“See what the fairies have brought, Mike.”

The policeman’s gaze shifted to the bills.

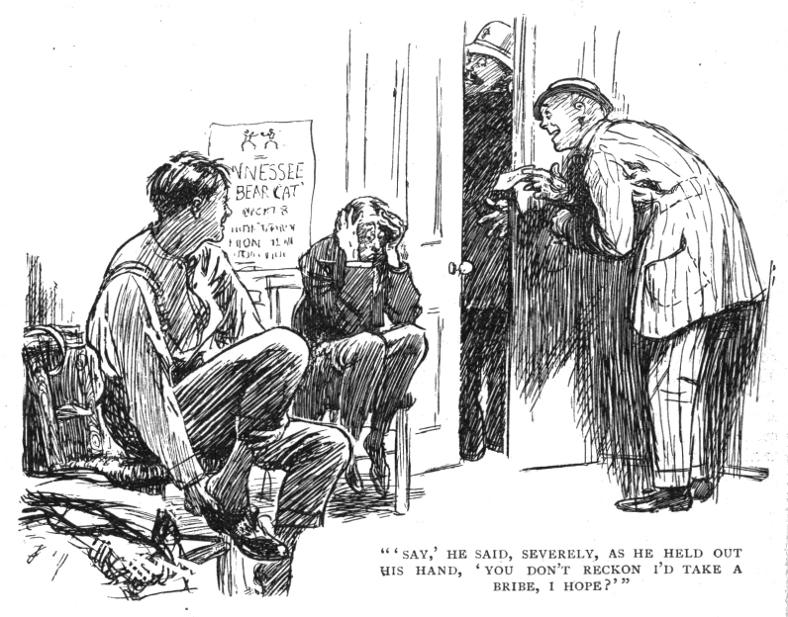

“Say,” he said, severely, as he held out his hand, “you don’t reckon I’d take a bribe, I hope?”

“Certainly not,” said the Bear-Cat, indignantly.

There was a musical rustling.

“Don’t mind if we say good night now, do you?” said the Bear-Cat. “They’ll be getting anxious about us at home.”

The policeman with the kind face met his colleague in the basement.

“Say, you know those guys in the dressing-room,” he said.

“Uh-huh,” said the colleague.

“They overpowered me and got away.”

“Halves,” said the colleague.

Having lost the Bear-Cat—no difficult task, for he dived into the first saloon—Mr. Bivatt and Freddie turned their steps towards Broadway. A certain dignity which had been lacking in the dressing-room had crept back into Mr. Bivatt’s manner.

“Go away,” he said. “I will not have you following me.”

“I am not following you,” said Freddie. “We are walking arm in arm.”

Mr. Bivatt wrenched himself free. “Go away, or I will call a police—er—go away!”

“Have you forgotten me? I was afraid you had. I won’t keep you long. I only wanted to tell you that I had nearly made that five hundred dollars.”

Mr. Bivatt started and glared at Freddie in the light of a shop-window. He gurgled speechlessly.

“I haven’t added it all up yet. I have been too busy making it. Let me see. Twelve dollars from the hotel. Two weeks as a waiter at five a week. Twenty-two. Tips, about another dollar. Three hundred for the loser’s end—I can’t claim a draw, as I was practically out. And ‘Blinky’ Anderson promised me another hundred if I stayed five rounds. Well I was on my feet when the police broke up the show, but maybe, after what has happened, he won’t pay up. Anyway, I’ve got three hundred and twenty-three——”

“Will you kindly stop this foolery and allow me to speak?” said Mr. Bivatt. “When I made our agreement I naturally alluded to responsible, respectable work. I did not include low prize-fighting and——”

“You said manual work or brain work. Wasn’t mine about as manual as you could get?”

“I have nothing further to say.”

Freddie sighed.

“Oh, well,” he said, “I suppose I shall have to start all over again. I wish you had let me know sooner. I shall try brain work this time. I shall write my experiences and try and sell them to a paper. What happened to-night ought to please some editor. The way you got us out of that dressing-room! It was the smartest thing I ever saw. There ought to be money in that. Well, good night. May I come and report later?”

He turned away, but stopped as he heard an odd choking sound behind him.

“Is anything the matter?”

Mr. Bivatt clutched him with one hand and patted his arm affectionately with the other.

“Don’t—er—don’t go away, my boy,” he said. “Come with me to the drug-store while I get some pepsine tabloids, and then we’ll go home and talk it over. I think we may be able to arrange something, after all.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums