The Strand Magazine, February 1920

PLEASANT breeze played among the trees on the terrace

outside the Marvis Bay Golf and Country Club. It ruffled the leaves and

cooled the forehead of the Oldest Member, who, as was his custom of a

Saturday afternoon, sat in the shade on a rocking-chair, observing the

younger generation as it hooked and sliced in the valley below. The eye

of the Oldest Member was thoughtful and reflective. When it looked into

yours you saw in it that perfect peace, that peace beyond understanding,

which comes at its maximum only to the man who has given up golf.

PLEASANT breeze played among the trees on the terrace

outside the Marvis Bay Golf and Country Club. It ruffled the leaves and

cooled the forehead of the Oldest Member, who, as was his custom of a

Saturday afternoon, sat in the shade on a rocking-chair, observing the

younger generation as it hooked and sliced in the valley below. The eye

of the Oldest Member was thoughtful and reflective. When it looked into

yours you saw in it that perfect peace, that peace beyond understanding,

which comes at its maximum only to the man who has given up golf.

The Oldest Member has not played golf since the rubber-cored ball superseded the old dignified gutty. But as a spectator and philosopher he still finds pleasure in the pastime. He is watching it now with keen interest. His gaze, passing from the lemonade which he is sucking through a straw, rests upon the Saturday foursome which is struggling raggedly up the hill to the ninth green. Like all Saturday foursomes, it is in difficulties. One of the patients is zigzagging about the fairway like a liner pursued by submarines. Two others seem to be digging for buried treasure, unless—it is too far off to be certain—they are killing snakes. The remaining cripple, who has just foozled a mashie-shot, is blaming his caddie. His voice, as he upbraids the innocent child for breathing during his up-swing, comes clearly up the hill.

The Oldest Member sighs. His lemonade gives a sympathetic gurgle. He puts it down on the table.

How few men, says the Oldest Member, possess the proper golfing temperament! How few indeed, judging by the sights I see here on Saturday afternoons, possess any qualification at all for golf except a pair of baggy knickerbockers and enough money to enable them to pay for the drinks at the end of the round. The ideal golfer never loses his temper. When I played, I never lost my temper. Sometimes, it is true, I may, after missing a shot, have broken my club across my knees; but I did it in a calm and judicial spirit, because the club was obviously no good and I was going to get another one anyway. To lose one’s temper at golf is foolish. It gets you nothing, not even relief. Imitate the spirit of Marcus Aurelius. “Whatever may befall thee,” says that great man in his “Meditations,” “it was preordained for thee from everlasting. Nothing happens to anybody which he is not fitted by nature to bear.” I like to think that this noble thought came to him after he had sliced a couple of new balls into the woods, and that he jotted it down on the back of his score-card. For there can be no doubt that the man was a golfer, and a bad golfer at that. Nobody who had not had a short putt stop on the edge of the hole could possibly have written the words: “That which makes the man no worse than he was makes life no worse. It has no power to harm, without or within.” Yes, Marcus Aurelius undoubtedly played golf, and all the evidence seems to indicate that he rarely went round in under a hundred and twenty. The niblick was his club.

Speaking of Marcus Aurelius and the golfing temperament recalls to my mind the case of young Mitchell Holmes. Mitchell, when I knew him first, was a promising young man with a future before him in the Paterson Dyeing and Refining Company, of which my old friend, Alexander Paterson, was the president. He had many engaging qualities—among them an unquestioned ability to imitate a bulldog quarrelling with a Pekingese in a way which had to be heard to be believed. It was a gift which made him much in demand at social gatherings in the neighbourhood, marking him off from other young men who could only almost play the mandolin or recite bits of Gunga Din; and no doubt it was this talent of his which first sowed the seeds of love in the heart of Millicent Boyd. Women are essentially hero-worshippers, and when a warm-hearted girl like Millicent has heard a personable young man imitating a bulldog and a Pekingese to the applause of a crowded drawing-room, and has been able to detect the exact point at which the Pekingese leaves off and the bulldog begins, she can never feel quite the same to other men. In short, Mitchell and Millicent were engaged, and were only waiting to be married till the former could bite the Dyeing and Refining Company’s ear for a bit of extra salary.

Mitchell Holmes had only one fault. He lost his temper when playing golf. He seldom played a round without becoming piqued, peeved, or—in many cases—chagrined. The caddies on our links, it was said, could always worst other small boys in verbal argument by calling them some of the things they had heard Mitchell call his ball on discovering it in a cuppy lie. He had a great gift of language, and he used it unsparingly. I will admit that there was some excuse for the man. He had the makings of a brilliant golfer, but a combination of bad luck and inconsistent play invariably robbed him of the fruits of his skill. He was the sort of player who does the first two holes in one under bogey and then takes an eleven at the third. The least thing upset him on the links. He missed short putts because of the uproar of the butterflies in the adjoining meadows.

It seemed hardly likely that this one kink in an otherwise admirable character would ever seriously affect his working or professional life, but it did. One evening, as I was sitting in my garden, reading Taylor on the push-shot, Alexander Paterson was announced. A glance at his face told me that he had come to ask my advice. Rightly or wrongly, he regarded me as one capable of giving advice. It was I who had changed the whole current of his life by counselling him to leave the wood in his bag and take a driving-iron off the tee; and in one or two other matters, like the choice of a putter (so much more important than the choice of a wife), I had been of assistance to him.

Alexander sat down and fanned himself with his hat, for the evening was warm. Perplexity was written upon his fine face.

“I don’t know what to do,” he said.

“Keep the head still—slow back—don’t press,” I said, gravely. There is no better rule for a happy and successful life.

He did not keep his head still. He shook it.

“It’s nothing to do with golf this time,” he said. “It’s about the treasurership of my company. Old Smithers retires next week, and I’ve got to find a man to fill his place.”

“That should be easy. You have simply to select the most deserving from among your other employés.”

“But which is the most deserving? That’s the point. There are two men who are capable of holding the job quite adequately. But then I realize how little I know of their real characters. It is the treasurership, you understand, which has to be filled. Now, a man who was quite good at another job might easily get wrong ideas into his head when he became a treasurer. He would have the handling of large sums of money. In other words, a man who in ordinary circumstances had never been conscious of any desire to visit the more distant portions of South America might feel the urge, so to speak, shortly after he became a treasurer. That is my difficulty. Of course, one always takes a sporting chance with any treasurer; but how am I to find out which of these two men would give me the more reasonable opportunity of keeping some of my money?”

I did not hesitate a moment. I held strong views on the subject of character-testing.

“The only way,” I said to Alexander, “of really finding out a man’s true character is to play golf with him. In no other walk of life does the cloven hoof so quickly display itself. I employed a lawyer for years, until one day I saw him kick his ball out of a heel-mark. I removed my business from his charge next morning. He has not yet run off with any trust-funds, but there is a nasty gleam in his eye, and I am convinced that it is only a question of time. Golf, my dear fellow, is the infallible test. The man who can go into a patch of rough alone, with the knowledge that only God is watching him, and play his ball where it lies, is the man who will serve you faithfully and well. The man who can smile bravely when his putt is diverted by one of those beastly worm-casts is pure gold right through. But the man who is hasty, unbalanced, and violent on the links will display the same qualities in the wider field of everyday life. You don’t want an unbalanced treasurer, do you?”

“Not if his books are likely to catch the complaint.”

“They are sure to. Statisticians estimate that the average of crime among good golfers is lower than in any class of the community except possibly bishops. Since Willie Park won the first championship at Prestwick in the year 1860 there has, I believe, been no instance of an Open Champion spending a day in prison. Whereas the bad golfers—and by bad I do not mean incompetent, but black-souled—the men who fail to count a stroke when they miss the globe: the men who never replace a divot: the men who talk while their opponent is driving: and the men who let their angry passions rise—these are in and out of Wormwood Scrubbs all the time. They find it hardly worth while to get their hair cut in their brief intervals of liberty.”

Alexander was visibly impressed.

“That sounds sensible, by George!” he said.

“It is sensible.”

“I’ll do it! Honestly, I can’t see any other way of deciding between Holmes and Dixon.”

I started.

“Holmes? Not Mitchell Holmes?”

“Yes. Of course you must know him? He lives here, I believe.”

“And by Dixon do you mean Rupert Dixon?”

“That’s the man. Another neighbour of yours.”

I confess that my heart sank. It was as if my ball had fallen into the pit which my niblick had digged. I wished heartily that I had thought of waiting to ascertain the names of the two rivals before offering my scheme. I was extremely fond of Mitchell Holmes and of the girl to whom he was engaged to be married. Indeed, it was I who had sketched out a few rough notes for the lad to use when proposing: and results had shown that he had put my stuff across well. And I had listened many a time with a sympathetic ear to his hopes in the matter of securing a rise of salary which would enable him to get married. Somehow, when Alexander was talking, it had not occurred to me that young Holmes might be in the running for so important an office as the treasurership. Now, when it was too late, I perceived that I had been the unwitting means of laying him a stymie. I had ruined the boy’s chances. Ordeal by golf was the one test which he could not possibly undergo with success. Only a miracle could keep him from losing his temper, and I had expressly warned Alexander against such a man.

When I thought of his rival my heart sank still more. Rupert Dixon was rather an unpleasant young man, but the worst of his enemies could not accuse him of not possessing the golfing temperament. From the drive off the tee to the holing of the final putt he was uniformly suave.

When Alexander had gone, I sat in thought for some time. I was faced with a problem. Strictly speaking, no doubt, I had no right to take sides: and, though secrecy had not been enjoined upon me in so many words, I was very well aware that Alexander was under the impression that I would keep the thing under my hat and not reveal to either party the test that awaited him. Each candidate was, of course, to remain ignorant that he was taking part in anything but a friendly game.

But when I thought of the young couple whose future depended on this ordeal, I hesitated no longer. I put on my hat and went round to Miss Boyd’s house, where I knew that Mitchell was to be found at this hour.

The young couple were out in the porch, looking at the moon. They greeted me heartily, but their heartiness had rather a tinny sound, and I could see that on the whole they regarded me as one of those things which should not happen. But when I told my story their attitude changed. They began to look on me in the pleasanter light of a guardian, philosopher, and friend.

“Wherever did Mr. Paterson get such a silly idea?” said Miss Boyd, indignantly. I had—from the best motives—concealed the source of the scheme. “It’s ridiculous!”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Mitchell. “The old boy’s crazy about golf. It’s just the sort of scheme he would cook up. Well, it dishes me!”

“Oh, come!” I said.

“It’s no good saying ‘Oh, come!’ You know perfectly well that I’m a frank, outspoken golfer. When my ball goes off nor’-nor’-east when I want it to go due west I can’t help expressing an opinion about it. It is a curious phenomenon which calls for comment, and I give it. Similarly, when I top my drive, I have to go on record as saying that I did not do it intentionally. And it’s just these trifles, as far as I can make out, that are going to decide the thing.”

“Couldn’t you learn to control yourself on the links, Mitchell, darling?” asked Millicent. “After all, golf is only a game!”

Mitchell’s eyes met mine, and I have no doubt that mine showed just the same look of horror which I saw in his. Women say these things without thinking. It does not mean that there is any kink in their character. They simply don’t realize what they are saying.

“Hush!” said Mitchell, huskily, patting her hand and overcoming his emotion with a strong effort. “Hush, dearest!”

Two or three days later I met Millicent coming from the post-office. There was a new light of happiness in her eyes, and her face was glowing.

“Such a splendid thing has happened,” she said. “After Mitchell left that night I happened to be glancing through a magazine, and I came across a wonderful advertisement. It began by saying that all the great men in history owed their success to being able to control themselves, and that Napoleon wouldn’t have amounted to anything if he had not curbed his fiery nature, and then it said that we can all be like Napoleon if we fill in the accompanying blank order-form for Professor Orlando Rollitt’s wonderful book, ‘Are You Your Own Master?’ absolutely free for five days and then seven shillings, but you must write at once because the demand is enormous and pretty soon it may be too late. I wrote at once, and luckily I was in time, because Professor Rollitt did have a copy left, and it’s just arrived. I’ve been looking through it, and it seems splendid.”

She held out a small volume. I glanced at it. There was a frontispiece showing a signed photograph of Professor Orlando Rollitt controlling himself in spite of having long white whiskers, and then some reading matter, printed between wide margins. One look at the book told me the professor’s methods. To be brief, he had simply swiped Marcus Aurelius’s best stuff, the copyright having expired some two thousand years ago, and was retailing it as his own. I did not mention this to Millicent. It was no affair of mine. Presumably, however obscure the necessity, Professor Rollitt had to live.

“I’m going to start Mitchell on it today. Don’t you think this is good? ‘Thou seest how few be the things which if a man has at his command his life flows gently on and is divine.’ I think it will be wonderful if Mitchell’s life flows gently on and is divine for seven shillings, don’t you?”

At the club-house that evening I encountered Rupert Dixon. He was emerging from a shower-bath, and looked as pleased with himself as usual.

“Just been going round with old Paterson,” he said. “He was asking after you. He’s gone back to town in his car.”

I was thrilled. So the test had begun!

“How did you come out?” I asked.

Rupert Dixon smirked. A smirking man, wrapped in a bath towel, with a wisp of wet hair over one eye, is a repellent sight.

“Oh, pretty well. I won by six and five. In spite of having poisonous luck.”

I felt a gleam of hope at these last words.

I felt a gleam of hope at these last words.

“Oh, you had bad luck?”

“The worst. I over-shot the green at the third with the best brassey-shot I’ve ever made in my life—and that’s saying a lot—and lost my ball in the rough beyond it.”

“And I suppose you let yourself go, eh?”

“Let myself go?”

“I take it that you made some sort of demonstration?”

“Oh, no. Losing your temper doesn’t get you anywhere at golf. It only spoils your next shot.”

I went away heavy-hearted. Dixon had plainly come through the ordeal as well as any man could have done. I expected to hear every day that the vacant treasurership had been filled, and that Mitchell had not even been called upon to play his test round. I suppose, however, that Alexander Paterson felt that it would be unfair to the other competitor not to give him his chance, for the next I heard of the matter was when Mitchell Holmes rang me up on the Friday and asked me if I would accompany him round the links next day in the match he was playing with Alexander, and give him my moral support.

“I shall need it,” he said. “I don’t mind telling you I’m pretty nervous. I wish I had had longer to get the stranglehold on that ‘Are You Your Own Master?’ stuff. I can see, of course, that it is the real tabasco from start to finish, and absolutely as mother makes it, but the trouble is I’ve only had a few days to soak it into my system. It’s like trying to patch up a motor car with string. You never know when the thing will break down. Heaven knows what will happen if I sink a ball at the water-hole. And something seems to tell me I am going to do it.”

There was a silence for a moment.

“Do you believe in dreams?” asked Mitchell.

“Believe in what?”

“Dreams.”

“What about them?”

“I said, ‘Do you believe in dreams?’ Because last night I dreamed that I was playing in the final of the Open Championship, and I got into the rough, and there was a cow there, and suddenly—I never experienced anything so vivid—the cow looked at me in a sad sort of way and said, ‘Why don’t you use the two-V grip instead of the interlocking?’ At the time it seemed an odd sort of thing to happen, but I’ve been thinking it over and I wonder if there isn’t something in it. These things must be sent to us for a purpose.”

“You can’t change your grip on the day of an important match.”

“I suppose not. The fact is, I’m a bit jumpy, or I wouldn’t have mentioned it. Oh, well! See you tomorrow at two.”

The day was bright and sunny, but a tricky cross-wind was blowing when I reached the club-house. Alexander Paterson was there, practising swings on the first tee: and almost immediately Mitchell Holmes arrived, accompanied by Millicent.

“Perhaps,” said Alexander, “we had better be getting under way. Shall I take the honour?”

“Certainly,” said Mitchell.

Alexander teed up his ball.

Alexander Paterson has always been a careful rather than a dashing player. It is his custom, a sort of ritual, to take two measured practice-swings before addressing the ball, even on the putting-green. When he does address the ball he shuffles his feet for a moment or two, then pauses, and scans the horizon in a suspicious sort of way, as if he had been expecting it to play some sort of a trick on him when he was not looking. A careful inspection seems to convince him of the horizon’s bona fides, and he turns his attention to the ball again. He shuffles his feet once more, then raises his club. He waggles the club smartly over the ball three times, then lays it behind the globule. At this point he suddenly peers at the horizon again, in the apparent hope of catching it off its guard. This done, he raises his club very slowly, brings it back very slowly till it almost touches the ball, raises it again, brings it down again, raises it once more, and brings it down for the third time. He then stands motionless, wrapped in thought, like some Indian fakir contemplating the infinite. Then he raises his club again and replaces it behind the ball. Finally he quivers all over, swings very slowly back, and drives the ball for about a hundred and fifty yards in a dead straight line.

It is a method of procedure which proves sometimes a little exasperating to the highly strung, and I watched Mitchell’s face anxiously to see how he was taking his first introduction to it. The unhappy lad had blenched visibly. He turned to me with the air of one in pain.

“Does he always do that?” he whispered.

“Always,” I replied.

“Then I’m done for! No human being could play golf against a one-ring circus like that without blowing up!”

I said nothing. It was, I feared, only too true. Well-poised as I am, I had long since been compelled to give up playing with Alexander Paterson, much as I esteemed him. It was a choice between that and resigning from the Baptist Church.

At this moment Millicent spoke. There was an open book in her hand. I recognized it as the life-work of Professor Rollitt.

“Think on this doctrine,” she said, in her soft, modulated voice, “that to be patient is a branch of justice, and that men sin without intending it.”

Mitchell nodded briefly, and walked to the tee with a firm step.

“Before you drive, darling,” said Millicent, “remember this. Let no act be done at haphazard, nor otherwise than according to the finished rules that govern its kind.”

The next moment Mitchell’s ball was shooting through the air, to come to rest two hundred yards down the course. It was a magnificent drive. He had followed the counsel of Marcus Aurelius to the letter.

An admirable iron-shot put him in reasonable proximity to the pin, and he holed out in one under bogey with one of the nicest putts I have ever beheld. And when at the next hole, the dangerous water-hole, his ball soared over the pond and lay safe, giving him bogey for the hole, I began for the first time to breathe freely. Every golfer has his day, and this was plainly Mitchell’s. He was playing faultless golf. If he could continue in this vein, his unfortunate failing would have no chance to show itself.

The third hole is long and tricky. You drive over a ravine—or possibly into it. In the latter event you breathe a prayer and call for your niblick. But, once over the ravine, there is nothing to disturb the equanimity. Bogey is five, and a good drive, followed by a brassey-shot, will put you within easy mashie-distance of the green.

Mitchell cleared the ravine by a hundred and twenty yards. He strolled back to me, and watched Alexander go through his ritual with an indulgent smile. I knew just how he was feeling. Never does the world seem so sweet and fair and the foibles of our fellow human beings so little irritating as when we have just swatted the pill right on the spot where it does most good.

“I can’t see why he does it,” said Mitchell, eyeing Alexander with a toleration that almost amounted to affection. “If I did all those Swedish exercises before I drove, I should forget what I had come out for and go home.” Alexander concluded the movements, and landed a bare three yards on the other side of the ravine. “He’s what you would call a steady performer, isn’t he? Never varies!”

Mitchell won the hole comfortably. There was a jauntiness about his stance on the fourth tee which made me a little uneasy. Over-confidence at golf is almost as bad as timidity.

My apprehensions were justified. Mitchell topped his ball. It rolled twenty yards into the rough, and nestled under a dock-leaf. His mouth opened, then closed with a snap. He came over to where Millicent and I were standing.

“I didn’t say it!” he said. “What on earth happened then?”

“Search men’s governing principles,” said Millicent, “and consider the wise, what they shun and what they cleave to.”

“Exactly,” I said. “You swayed your body.”

“And now I’ve got to go and look for that infernal ball.”

“Never mind, darling,” said Millicent. “Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life.”

“Besides,” I said, “you’re three up.”

“I sha’n’t be after this hole.”

He was right. Alexander won it in five, one above bogey, and regained the honour.

Mitchell was a trifle shaken. His play no longer had its first careless vigour. He lost the next hole, halved the sixth, lost the short seventh, and then, rallying, halved the eighth.

The ninth hole, like so many on our links, can be a perfectly simple four, although the rolling nature of the green makes bogey always a somewhat doubtful feat; but, on the other hand, if you foozle your drive, you can easily achieve double figures. The tee is on the farther side of the pond, beyond the bridge, where the water narrows almost to the dimensions of a brook. You drive across this water and over a tangle of trees and under-growth on the other bank. The distance to the fairway cannot be more than sixty yards, for the hazard is purely a mental one, and yet how many fair hopes have been wrecked there!

Alexander cleared the obstacles comfortably with his customary short, straight drive, and Mitchell advanced to the tee.

I think the loss of the honour had been preying on his mind. He seemed nervous. His up-swing was shaky, and he swayed back perceptibly. He made a lunge at the ball, sliced it, and it struck a tree on the other side of the water and fell in the long grass. We crossed the bridge to look for it; and it was here that the effect of Professor Rollitt began definitely to wane.

“Why on earth don’t they mow this darned stuff?”

demanded Mitchell, querulously, as he beat about the grass with his niblick.

“Why on earth don’t they mow this darned stuff?”

demanded Mitchell, querulously, as he beat about the grass with his niblick.

“You have to have rough on a course,” I ventured.

“Whatever happens at all,” said Millicent, “happens as it should. Thou wilt find this true if thou shouldst watch narrowly.”

“That’s all very well,” said Mitchell, watching narrowly in a clump of weeds but seeming unconvinced. “I believe the Greens Committee run this bally club purely in the interests of the caddies. I believe they encourage lost balls, and go halves with the little beasts when they find them and sell them!”

Millicent and I exchanged glances. There were tears in her eyes.

“Oh, Mitchell! Remember Napoleon!”

“Napoleon! What’s Napoleon got to do with it? Napoleon never was expected to drive through a primeval forest. Besides, what did Napoleon ever do? Where did Napoleon get off, swanking round as if he amounted to something? Poor fish! All he ever did was to get hammered at Waterloo!”

Alexander rejoined us. He had walked on to where his ball lay.

“Can’t find it, eh? Nasty bit of rough, this!”

“No, I can’t find it. But tomorrow some miserable, chinless, half-witted reptile of a caddie with pop eyes and eight hundred and thirty-seven pimples will find it, and will sell it to someone for sixpence! No, it was a brand-new ball. He’ll probably get a shilling for it. That’ll be sixpence for himself and sixpence for the Greens Committee. No wonder they’re buying cars quicker than the makers can supply them. No wonder you see their wives going about in mink coats and pearl necklaces. Oh, darn it! I’ll drop another!”

“In that case,” Alexander pointed out, “you will, of course, under the rules governing match-play, lose the hole.”

“All right, then. I’ll give up the hole.”

“Then that, I think, makes me one up on the first nine,” said Alexander. “Excellent! A very pleasant, even game.”

“Pleasant! On second thoughts I don’t believe the Greens Committee let the wretched caddies get any of the loot. They hang round behind trees till the deal’s concluded, and then sneak out and choke it out of them!”

I saw Alexander raise his eyebrows. He walked up the hill to the next tee with me.

“Rather a quick-tempered young fellow, Holmes!” he said, thoughtfully. “I should never have suspected it. It just shows how little one can know of a man, only meeting him in business hours.”

I tried to defend the poor lad.

“He has an excellent heart, Alexander. But the fact is—we are such old friends that I know you will forgive my mentioning it—your style of play gets, I fancy, a little on his nerves.”

“My style of play? What’s wrong with my style of play?”

“Nothing is actually wrong with it, but to a young and ardent spirit there is apt to be something a trifle upsetting in being compelled to watch a man play quite so slowly as you do. Come now, Alexander, as one friend to another, is it necessary to take two practice-swings before you putt?”

“Dear, dear!” said Alexander. “You really mean to say that that upsets him? Well, I’m afraid I am too old to change my methods now.”

I had nothing more to say.

As we reached the tenth tee, I saw that we were in for a few minutes’ wait. Suddenly I felt a hand on my arm. Millicent was standing beside me, dejection written on her face. Alexander and young Mitchell were some distance away from us.

“Mitchell doesn’t want me to come round the rest of the way with him,” she said, despondently. “He says I make him nervous.”

I shook my head.

“That’s bad! I was looking on you as a steadying influence.”

“I thought I was, too. But Mitchell says no. He says my being there keeps him from concentrating.”

“Then perhaps it would be better for you to remain in the club-house till we return. There is, I fear, dirty work ahead.”

A choking sob escaped the unhappy girl.

“I’m afraid so. There is an apple tree near the thirteenth hole, and Mitchell’s caddie is sure to start eating apples. I am thinking of what Mitchell will do when he hears the crunching when he is addressing his ball.”

“That is true.”

“Our only hope,” she said, holding out Professor Rollitt’s book, “is this. Will you please read him extracts when you see him getting nervous? We went through the book last night and marked all the passages in blue pencil which might prove helpful. You will see notes against them in the margin, showing when each is supposed to be used.”

It was a small favour to ask. I took the book and gripped her hand silently. Then I joined Alexander and Mitchell on the tenth tee. Mitchell was still continuing his speculations regarding the Greens Committee.

“The hole after this one,” he said, “used to be a short hole. There was no chance of losing a ball. Then, one day, the wife of one of the Greens Committee happened to mention that the baby needed new shoes, so now they’ve tacked on another hundred and fifty yards to it. You have to drive over the brow of a hill, and if you slice an eighth of an inch you get into a sort of No Man’s Land, full of rocks and bushes and crevices and old pots and pans. The Greens Committee practically live there in the summer. You see them prowling round in groups, encouraging each other with merry cries as they fill their sacks. Well, I’m going to fool them today. I’m going to drive an old ball which is just hanging together by a thread. It’ll come to pieces when they pick it up!”

Golf, however, is a curious game—a game of fluctuations. One might have supposed that Mitchell, in such a frame of mind, would have continued to come to grief. But at the beginning of the second nine he once more found his form. A perfect drive put him in position to reach the tenth green with an iron-shot, and, though the ball was several yards from the hole, he laid it dead with his approach-putt and holed his second for a bogey four. Alexander could only achieve a five, so that they were all square again.

The eleventh, the subject of Mitchell’s recent criticism, is certainly a tricky hole, and it is true that a slice does land the player in grave difficulties. Today, however, both men kept their drives straight, and found no difficulty in securing fours.

“A little more of this,” said Mitchell, beaming, “and the Greens Committee will have to give up piracy and go back to work.”

The twelfth is a long, dog-leg hole, bogey five. Alexander plugged steadily round the bend, holing out in six, and Mitchell, whose second shot had landed him in some long grass, was obliged to use his niblick. He contrived, however, to halve the hole with a nicely-judged mashie-shot to the edge of the green.

Alexander won the thirteenth. It is a three hundred and sixty yard hole, free from bunkers. It took Alexander three strokes to reach the green, but his third laid the ball dead; while Mitchell, who was on in two, required three putts.

“That reminds me,” said Alexander, chattily, “of a story I heard. Friend calls out to a beginner, ‘How are you getting on, old man?’ and the beginner says, ‘Splendidly. I just made three perfect putts on the last green!’ ”

Mitchell did not appear amused. I watched his face anxiously. He had made no remark, but the missed putt which would have saved the hole had been very short, and I feared the worst. There was a brooding look in his eye as we walked to the fourteenth tee.

There are few more picturesque spots in the whole of the countryside than the neighbourhood of the fourteenth tee. It is a sight to charm the nature-lover’s heart.

But, if golf has a defect, it is that it prevents a man being a whole-hearted lover of nature. Where the layman sees waving grass and romantic tangles of undergrowth, your golfer beholds nothing but a nasty patch of rough from which he must divert his ball. The cry of the birds, wheeling against the sky, is to the golfer merely something that may put him off his putt. As a spectator, I am fond of the ravine at the bottom of the slope. It pleases the eye. But, as a golfer, I have frequently found it the very devil.

The last hole had given Alexander the honour again. He drove even more deliberately than before. For quite half a minute he stood over his ball, pawing at it with his driving-iron like a cat investigating a tortoise. Finally he despatched it to one of the few safe spots on the hillside. The drive from this tee has to be carefully calculated, for, if it be too straight, it will catch the slope and roll down into the ravine.

Mitchell addressed his ball. He swung up, and then, from immediately behind him came a sudden sharp crunching sound. I looked quickly in the direction whence it came. Mitchell’s caddie, with a glassy look in his eyes, was gnawing a large apple. And even as I breathed a silent prayer, down came the driver, and the ball, with a terrible slice on it, hit the side of the hill and bounded into the ravine.

There was a pause—a pause in which the world stood still. Mitchell dropped his club and turned. His face was working horribly.

“Mitchell!” I cried. “My boy! Reflect! Be calm!”

“Calm! What’s the use of being calm when people are chewing apples in thousands all round you? What is this, anyway—a golf match or a pleasant day’s outing for the children of the poor? Apples! Go on, my boy, take another bite. Take several. Enjoy yourself! Never mind if it seems to cause me a fleeting annoyance. Go on with your lunch! You probably had a light breakfast, eh, and are feeling a little peckish, yes? If you will wait here, I will run to the clubhouse and get you a sandwich and a bottle of ginger-ale. Make yourself quite at home, you lovable little fellow! Sit down and have a good time!”

I turned the pages of Professor Rollitt’s book feverishly. I could not find a passage that had been marked in blue pencil to meet this emergency. I selected one at random.

“Mitchell,” I said, “one moment. How much time he gains who does not look to see what his neighbour says or does, but only at what he does himself, to make it just and holy.”

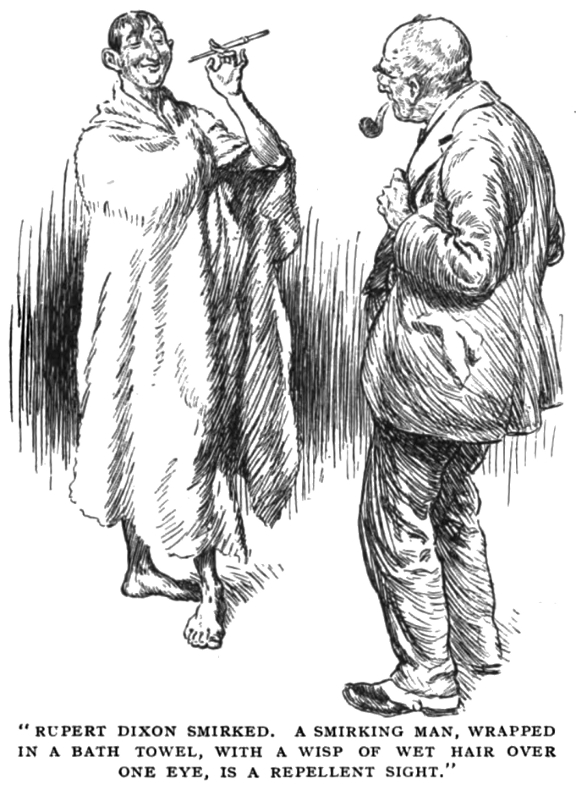

“Well, look what I’ve done myself! I’m somewhere down at the bottom of that dashed ravine, and it’ll take me a dozen strokes to get out. Do you call that just and holy? Here, give me that book for a moment!”

He snatched the little volume out of my hands. For an instant he looked at it with a curious expression of loathing, then he placed it gently on the ground and jumped on it a few times. Then he hit it with his driver. Finally, as if feeling that the time for half measures had passed, he took a little run and kicked it strongly into the long grass.

He turned to Alexander, who had been an impassive spectator of the scene.

“I’m through!” he said. “I concede the match. Good-bye. You’ll find me in the bay!”

“Going swimming?”

“No. Drowning myself!”

A gentle smile broke out over my old friend’s usually grave face. He patted Mitchell’s shoulder affectionately.

“Don’t do that, my boy,” he said. “I was hoping you would stick around the office awhile as treasurer of the company.”

Mitchell tottered. He grasped my arm for support. Everything was very still. Nothing broke the stillness but the humming of the bees, the murmur of the distant wavelets, and the sound of Mitchell’s caddie going on with his apple.

“What!” cried Mitchell.

“The position,” said Alexander, “will be falling vacant very shortly, as no doubt you know. It is yours, if you care to accept it.”

“You mean—you mean—you’re going to give me the job?”

“Certainly. You have interpreted me exactly.”

Mitchell gulped. So did his caddie. One from a spiritual, the other from a physical cause.

“If you don’t mind excusing me,” said Mitchell, huskily, “I think I’ll be popping back to the club-house. Someone I want to see.”

He disappeared through the trees, running strongly. I turned to Alexander.

“What does this mean?” I asked. “I am delighted, but what becomes of the test?”

My old friend smiled gently.

“The test,” he replied, “has been eminently satisfactory. Circumstances, perhaps, have compelled me to modify the original idea of it, but nevertheless it has been a completely successful test. Since we started out, I have been doing a good deal of thinking, and I have come to the conclusion that what the Paterson Dyeing and Refining Company really needs is a treasurer whom I can beat at golf. And I have discovered the ideal man. Why,” he went on, a look of holy enthusiasm on his fine old face, “do you realize that I can always lick the stuffing out of that boy, good player as he is, simply by taking a little trouble? I can make him get the wind up every time, simply by taking one or two extra practice-swings! That is the sort of man I need for a responsible post in my office.”

“But what about Rupert Dixon?” I asked.

He gave a gesture of distaste.

“I wouldn’t trust that man. Why, when I played with him, everything went wrong, and he just smiled and didn’t say a word. A man who can do that is not the man to trust with the control of large sums of money. It wouldn’t be safe. Why, the fellow isn’t honest! He can’t be.” He paused for a moment. “Besides,” he added, thoughtfully, “he beat me by six and five. What’s the good of a treasurer who beats the boss by six and five?”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums