The Strand Magazine, December 1913

A!”

A!”

Mrs. Bramble looked up, beaming with a kind of amiable fat-headedness. She was the stupidest woman in Barnes, and one of the best-tempered. A domestic creature, wrapped up in Bill, her husband, and Harold, her son. At the present moment only the latter was with her. He sat on the other side of the table, his lips gravely pursed and his eyes a trifle cloudy behind their spectacles. Before him on the red tablecloth lay an open book. His powerful brain was plainly busy.

Mrs. Bramble regarded him fondly. A boy scout, had one been present, would have been struck by the extraordinary resemblance to a sheep surprised while gloating over its young.

“Yes, dearie?”

“Will you hear me?”

Mrs. Bramble took the book.

“Yes, mother will hear you, precious.”

A slight frown marred the smoothness of Harold Bramble’s brow. It jarred upon him, this habit of his mother’s of referring to herself in the third person, as if she were addressing a baby, instead of a young man of ten who had taken the spelling and dictation prize last term on his head.

He cleared his throat and fixed his eyes upon the cut-glass hangings of the chandelier.

“ ‘Be good, sweet maid,’ ” he began, with the toneless rapidity affected by youths of his age when reciting poetry, “ ‘and let who will be clever’—clever, oh yes—‘do noble things, not dream them’—dream them, oh yes—‘dream them all day long; and so make life, death, and that vast f’rever, one’—oh yes—‘one grand, sweet song.’ I knew I knew it, and now I can do my Scripture.”

“You do study so hard, dearie, you’ll go giving yourself a headache. Why don’t you take a nice walk by the river for half an hour, and come back nice and fresh? It’s a nice evening, and you could do your Scripture nicely afterwards.”

The spectacled child considered the point for a moment gravely. Then, nodding, he arranged his books in readiness for his return and went out. The front door closed with a decorous softness.

It was a constant source of amazement to Mrs. Bramble that she should have brought such a prodigy as Harold into the world. Harold was so different from ordinary children, so devoted to his books, such a model of behaviour, so altogether admirable. The only drawback was that his very perfection had made necessary a series of evasions and even deliberate falsehoods on the part of herself and her husband, highly distasteful to both. They were lovers of truth, but they had realized that there are times when truth must be sacrificed. At any cost the facts concerning Mr. Bramble’s profession must be kept from Harold.

While he was a baby it had not mattered so much. But when he began to move about and take notice, Mrs. Bramble said to Mr. Bramble, “Bill, we must keep it from Harold.”

A little later, when the child had begun to show signs of being about to become a model of goodness and intelligence, and had already taken two prizes at the Sunday-school, the senior curate of the parish, meeting Mr. Bramble one morning, said, nervously—for, after all, it was a delicate subject to broach—“Er—Bramble, I think, on the whole, it would be as well to—er—keep it from Harold.”

And only the other day, Mrs. Bramble’s brother, Major Percy Stokes, of the Salvation Army, dropping in for a cup of tea, had said, “I hope you are keeping it from Harold. It is the least you can do,” and had gone on to make one or two remarks about men of wrath which, considering that his cheek-bones were glistening with Mr. Bramble’s buttered toast, were in poor taste. But Percy was like that. Enemies said that he liked the sound of his own voice, and could talk the hind-leg off a donkey. Certainly he was very persuasive. Once he had wrought so successfully with an emotional publican in East Dulwich that the latter had started then and there to give all that he had to the poor, beginning with his stock-in-trade. Seven policemen had almost failed to handle the situation.

Mr. Bramble had fallen in with the suggestion without demur. In private life he was the mildest and most obliging of men, and always yielded to everybody. The very naming of Harold had caused a sacrifice on his part. When it was certain that he was about to become a father he had expressed a desire that the child should be named John, if a boy, after Mr. John L. Sullivan, or, if a girl, Marie, after Miss Marie Lloyd. But Mrs. Bramble saying that Harold was such a sweet name, he had withdrawn his suggestions with the utmost good-humour.

Nobody could help liking this excellent man; which made it all the greater pity that his walk in life was of such a nature that it simply had to be kept from Harold.

He was a professional pugilist! That was the trouble.

Before the coming of Harold he had been proud of being a professional pugilist. His ability to paste his fellow-man in the eye while apparently meditating an attack on his stomach, and vice versâ, had filled him with that genial glow of self-satisfaction which comes to philanthropists and other benefactors of the species. It had seemed to him a thing on which to congratulate himself that of all London’s teeming millions there was not a man, weighing eight stone four, whom he could not overcome in a twenty-round contest. He was delighted to be the possessor of a left hook which had won the approval of the newspapers.

And then Harold had come into his life, and changed him into a furtive practiser of shady deeds. Before, he had gone about the world with a match-box full of press-notices, which he would extract with a pin and read to casual acquaintances. Now, he quailed at the sight of his name in print, so thoroughly had he become imbued with the necessity of keeping it from Harold.

With an ordinary boy it would have mattered less. But Harold was different. Secretly proud of him as they were, both Bill and his wife were a little afraid of their wonderful child. The fact was, as Bill himself put it, Harold was showing a bit too much class for them. He had formed a corner in brains, as far as the Bramble family was concerned. They had come to regard him as a being of a superior order. Bill himself could never think without getting a headache, and Mrs. Bramble’s placid stupidity had been a byword at the A.B.C. shop in which she had served before her marriage. Yet Harold, defying the laws of heredity, had run to intellect as his father had run to muscle. He had learned to read and write with amazing quickness. He sang in the choir. He attended Sunday-school with a vim which drew warm commendation from the vicar. And now, at the age of ten, a pupil at a local private school where they wore mortar-boards and generally comported themselves like young dons, he had already won a prize for spelling and dictation, and was considered by those in the know a warm man for the Junior Scripture. You simply couldn’t take a boy like that aside and tell him that the father whom he believed to be a commercial traveller was affectionately known to a large section of the inhabitants of London as “Young Porky.” There were no two ways about it. You had to keep it from him.

So Harold grew in stature and intelligence, without a suspicion of the real identity of the square-jawed man with the irregularly-shaped nose who came and went mysteriously in their semi-detached, red-brick home. He was a self-centred child, and, accepting the commercial traveller fiction, dismissed the subject from his mind and busied himself with things of more moment. And time slipped by.

Mrs. Bramble, left alone, resumed work on the sock which she was darning. For the first time since Harold had reached years of intelligence she was easy in her mind about the future. A week from to-night would see the end of all her anxieties. On that day Bill would fight his last fight, the twenty-round contest with that American Murphy at the National Sporting Club for which he was now training at the White Hart down the road. He had promised that it should be the last. He was getting on. He was thirty-one, and he said himself that he would have to be chucking the game before it chucked him. His idea was to retire from active work and try for a job as instructor at one of these big schools or colleges. He had a splendid record for respectability and sobriety and all the other qualities which headmasters demanded in those who taught their young gentlemen to box; and several of his friends who had obtained similar posts described the job in question as extremely soft. So that it seemed to Mrs. Bramble that all might now be considered well. She smiled happily to herself as she darned her sock.

She was interrupted in her meditations by a knock at the front door. She put down her sock and listened. It was late for any of the neighbours to pay a call, and the knock had puzzled her. Martha, the general, pattered along the passage, and then there came the sound of voices speaking in an undertone. Footsteps made themselves heard in the passage. The door opened. The head and shoulders of Major Percy Stokes insinuated themselves into the room.

The major cocked a mild blue eye at her.

“Harold anywhere about?”

“He’s gone out for a nice walk. Whatever brings you here, Percy, so late?”

Percy made no answer. He withdrew his head. His voice, without, said “All right.” He then reappeared, this time in his entirety, and remained holding the door open. More footsteps in the passage, and through the doorway, in a sideways fashion suggestive of a diffident crab, came a short, sturdy, redheaded man with a broken nose and a propitiatory smile, at the sight of whom Mrs. Bramble, dropping her sock, rose as if propelled by powerful machinery, and exclaimed, “Bill!”

Mr. Bramble—for it was he—scratched his head, grinned feebly, and looked for assistance to the major.

“A brand from the burning,” said that gentleman.

“That’s right,” said Mr. Bramble; “that’s me.”

“The scales have fallen from his eyes.”

“What scales?” demanded Mrs. Bramble, a literal-minded woman. “And what are you doing here, Bill, when you ought to be at the White Hart, training?”

“That’s just what I’m telling you,” said Percy. ”I been wrestling with Bill, and I been vouchsafed the victory.”

“You!” said Mrs. Bramble, with uncomplimentary astonishment, letting her gaze wander over her brother’s weedy form.

“I been vouchsafed the victory,” repeated the major. “It was ’ard work, but did I falter? No, I did not falter. There were moments when it didn’t seem ’ardly possible I could bring it off, but was I down-hearted? No, I was not down-hearted. I wrote him letters, and I sent him tracts. I tried to wrestle with him in speech, too, but there was a man of wrath, a son of Belial in a woollen jersey and a bowler hat, who come at me, using horrible language, and told me to stand still while he broke my neck and dropped me into the river.”

“Jerry Fisher’s a hard nut,” said Mr. Bramble, apologetically. “He don’t like people coming round talking to a man he’s training, unless he introduces them or they’re newspaper gents.”

“After that I kept away. But I wrote the letters and I sent the tracts. Bill, which of the tracts was it that snatched you from the primrose path?”

“It wasn’t so much the tracts, Perce. It was what you wrote about Harold. You see, Jane——”

“Perhaps you’ll kindly allow me to get a word in edgeways, you two,” said Mrs. Bramble, her temper for once becoming ruffled. “You can stop talking for half an instant, Percy, if you know how, while Bill tells me what he’s doing here when he ought to be at the White Hart with Mr. Fisher, doing his bit of training.”

Mr. Bramble met her eye and blinked awkwardly.

“Percy’s just been telling you, Jane. He wrote——”

“I haven’t made head or tail of a word that Percy’s said, and I don’t expect to. All I want is a plain answer to a plain question. What are you doing here, Bill, instead of being at the White Hart?”

“I’ve come home, Jane.”

“Glory!” exclaimed the major.

“Percy, if you don’t keep quiet, I’ll forget I’m your sister and let you have one. What do you mean, Bill, you’ve come home? Isn’t there going to be the fight next week, after all?”

“The fight’s over,” said the unsuppressed major, joyfully, “and Bill’s won, with me seconding him.”

“Percy!”

Mr. Bramble pulled himself together with a visible effort.

“I’m not going to fight, Jane,” he said, in a small voice.

“You’re not going——!”

“He’s seen the error of his ways,” cried Percy, the resilient. “That’s what he’s gone and done. At the eleventh hour it has been vouchsafed to me to snatch the brand from the burning. Oh! I have waited for this joyful moment. I have watched for it. I——”

“You’re not going to fight!”

Mr. Bramble, avoiding his wife’s eye, shook his head.

“And how about the money?”

“What’s money?” said the major, scornfully.

“You ought to know,” snapped Mrs. Bramble, turning on him. “You’ve borrowed enough of it from me in your time.”

The major waved a hand in wounded silence. He considered the remark In poor taste. It was true that from time to time a certain amount of dross had passed from her hands to his, but this harping on the fact was indelicate and unsisterly.

“How about the money?” repeated Mrs. Bramble. “Goodness knows I’ve never liked your profession, Bill, but there is this to be said for it, that it’s earned you good money and made it possible for us to give Harold as good an education as any duke ever had, I’m sure. And you know yourself you said that the five hundred pounds you were going to get if you beat this Murphy, and even if you lost it would be a hundred and twenty, was going to be a blessing, because it would let us finish him off proper and give him a better start in life than you or me ever had, and now you let this Percy come over you with his foolish talk, and now I don’t know what will happen.”

There was an uncomfortable silence. Even Percy seemed at a loss for words. Mrs. Bramble sat down and began to sob. Mr. Bramble shuffled his feet.

“Talking of Harold,” said Mr. Bramble at last, “that’s really what I’m driving at. It was him really what I was thinking of when I hopped it from the White Hart. There’s a good deal in what Perce says about men of wrath and the primrose path and all, but it was Harold that really made me do it. It hadn’t hardly struck me till Perce pointed it out, but this fight with Jimmy Murphy, being as you might say a kind of national affair, in a way of speaking, was likely to be written up in all the papers, instead of only in the sporting ones. As likely as not there would be a piece about it in the Mail, with a photograph of me. And you know Harold reads his Mail regular. And then, don’t you see, the fat would be in the fire. That’s what Percy pointed out to me, and I seen what he meant, so I hopped it.”

“At the eleventh hour,” added the major, rubbing in the point.

“You see, Jane——” Mr. Bramble was beginning, when there was a knock at the door, and a little, ferret-faced man in a woollen sweater and cycling knickerbockers entered, removing as he did so a somewhat battered bowler hat.

“Beg pardon, Mrs. Bramble,” he said, “coming in like this. Found the front door on the jar, so came in to ask if you’d happened to have seen——”

He broke off and stood staring wildly at the little group.

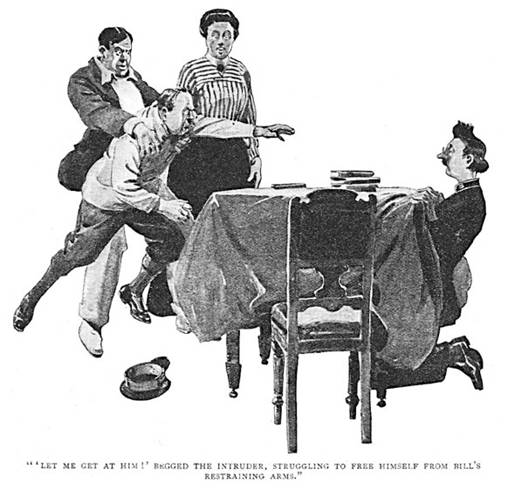

“I thought so!” he said, and shot through the air towards Percy.

“Jerry!” said Bill.

“Mr. Fisher!” said Mrs. Bramble.

“Be reasonable,” said the major, diving underneath the table and coming up the other side like a performing seal.

“Let me get at him,” begged the intruder, struggling to free himself from Bill’s restraining arms.

Mrs. Bramble rapped on the table.

“Kindly remember there’s a lady present, Mr. Fisher.”

The little man’s face became a battlefield on which rage, misery, and a respect for the decencies of social life struggled for the mastery.

“It’s hard,” he said at length, in a choked voice. “I just wanted to break his neck for him, but I suppose it’s not to be. I know it’s him that’s at the bottom of it. Directly I found Bill, here, had cut his stick and hopped it, I says to myself, ’It’s him!’ And here I find them together, so I know it’s him. Well, if you say so, Mrs. B., I suppose I mustn’t put a head on him. But it’s hard. Bill, you come back along of me to the White Hart. I’m surprised at you. Ashamed of you, I am. All the time you and me have known each other I’ve never known you do such a thing. You such a pleasure to train as a rule. It all comes of getting with bad companions. And your chop cooking on the fire all the while! It’ll be spoilt now, and all the expense of ordering another. It’s hard. Come along, Bill. Step it.”

Mr. Bramble looked at his brother-in-law miserably.

“You tell him,” he said.

“You tell him, Jane,” said the major.

“I won’t,” said Mrs. Bramble.

“Tell him what?” asked the puzzled trainer. A sudden thought blanched his face. “You haven’t been having a glass of beer, Bill?”

“No, no, Jerry. Not me. It’s only that——”

“Well?”

“It’s only that I’m not going to fight on Monday.”

“What!”

“Bill has seen a sudden bright light,” said Percy, edging a few inches to the left, so that the table was exactly between the trainer and himself. “At the eleventh hour he has turned from his wicked ways. You ought to be singing with joy, Mr. Fisher, if you really loved Bill. This ought to be the happiest evening you’ve ever known. You ought to be singing like a little child.”

A strange, guttural noise escaped the trainer. It may have been a song, but it did not sound like it.

“It’s true, Jerry,” said Bill, unhappily. “I been thinking it over, and I’m not going to fight on Monday.”

“Glory!” said the major, tactlessly.

Jerry Fisher’s face was a study in violent emotions. His eyes seemed to protrude from their sockets like a snail’s. He clutched the tablecloth.

“I’m sorry, Jerry,” said Bill. “I know it’s hard on you. But I’ve got to think of Harold. This fight with Jimmy Murphy being what you might call a kind of national affair, in a way of speaking, will be reported in the Mail as like as not, with a photograph of me, and Harold reads his Mail regular. We’ve been keeping it from him all these years that I’m in the profession, and we dursen’t let him know now. He would die of shame, Jerry.”

Tears appeared in Jerry Fisher’s eyes.

“Bill,” he cried, “you’re off your head. Think of the purse!”

“Ah!” said Mrs. Bramble.

“Think of all the swells that’ll be coming to see you. Think of the Lonsdale belt they’ll have to let you try for if you beat this Murphy. Think of what the papers’ll say. Think of me.”

“I know, Jerry, it’s chronic. But Harold——”

“Think of all the trouble you’ve took for the last weeks getting yourself into condition.”

“I know. But Har——”

“You can’t not fight on Monday. It ’ud be too hard.”

“But Harold, Jerry. He’d die of the disgrace of it. He ain’t like you and me, Jerry. He’s a little gentleman. I got to think of Harold.”

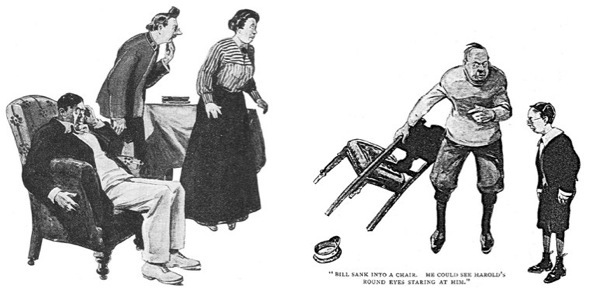

“What about me, pa?” said a youthful voice at the door; and Bill’s honest blood froze at the sound. His jaw fell, and he goggled dumbly.

There, his spectacles gleaming in the gaslight, his cheeks glowing with the exertion of the nice walk, his eyebrows slightly elevated with surprise, stood Harold himself.

“Halloa, pa! Halloa, Uncle Percy! Somebody’s left the front door open. What were you saying about thinking about me, pa? Ma, will you hear me my piece of poetry again? I think I’ve forgotten it.”

The four adults surveyed the innocent child in silence.

On the faces of three of them consternation was written. In the eyes of the fourth, Mr. Fisher, there glittered that nasty, steely expression of the man who sees his way to getting a bit of his own back. Mr. Fisher’s was not an unmixedly chivalrous nature. He considered that he had been badly treated, and what he wanted most at the moment was revenge. He had been fond and proud of Bill Bramble, but those emotions belonged to the dead past. Just at present he felt that he disliked Bill rather more than anyone else in the world, with the possible exception of Major Percy Stokes.

“So you’re Harold, are you, Tommy?” he said, in a metallic voice. “Then just you listen here a minute.”

“Jerry,” cried Bill, advancing, “you keep your mouth shut, or I’ll dot you one.”

Mr. Fisher retreated and, grasping a chair, swung it above his head.

“You better!” he said, curtly.

“Mr. Fisher, do be a gentleman,” entreated Mrs. Bramble.

“My dear sir.” There was a crooning winningness in Percy’s voice. “My dear sir, do nothing hasty. Think before you speak. Don’t go and be so silly as to act like a muttonhead. I’d be ashamed to be so spiteful. Respect a father’s feelings.”

“Tommy,” said Mr. Fisher, ignoring them all, “you think your pa’s a commercial. He ain’t. He’s a fighting-man, doing his eight-stone-four ringside, and known to all the heads as ‘Young Porky.’ ”

Bill sank into a chair. He could see Harold’s round eyes staring at him.

“I’d never have thought it of you, Jerry,” he said, miserably. “If anyone had come to me and told me that you could have acted so raw I’d have dotted him one.”

“And if anyone had come to me and told me that I should live to see the day when you broke training a week before a fight at the National I’d given him one for himself.”

“Harold, my lad,” said Percy, “you mustn’t think none the worse of your pa for having been a man of wrath. He hadn’t seen the bright light then. It’s all over now. He’s give it up for ever, and there’s no call for you to feel ashamed.”

Bill seized on the point.

“That’s right, Harold,” he said, reviving. “I’ve give it up; I was to have fought an American named Murphy at the National next Monday, but I ain’t going to now, not if they come to me on their bended knees. Not if the King of England come to me on his bended knees.”

Harold drew a deep breath.

“Oh?” he cried, shrilly. “Oh, aren’t you? Then what about my two bob? What about my two bob I’ve betted Dicky Saunders that Jimmy Murphy won’t last ten rounds?”

He looked round the room wrathfully.

“It’s thick,” he said, in the crisp, gentlemanly voice of which his parents were so proud. “It’s jolly thick. That’s what it is. A chap takes the trouble to study form and saves up his pocket-money to have a bit on a good thing, and then he goes and gets let down like this. It may be funny to you, but I call it rotten. And another thing I call rotten is you having kept it from me all this time that you were ‘Young Porky,’ pa. That’s what I call so jolly rotten! There’s a fellow at our school who goes about swanking in the most rotten way because he once got Bombardier Wells’s autograph. Fellows look up to him most awfully, and all the time they might have been doing it to me. That’s what makes me so jolly sick. How long do you suppose they’d go on calling me ‘Goggles’ if they knew that you were my father? They’d chuck it to-morrow, and look up to me like anything. I do call it rotten. And chucking it up like this is the limit. What do you want to do it for? It’s the silliest idea I ever heard. Why, if you beat Jimmy Murphy they’ll have to give you the next chance with Sid Sampson for the Lonsdale belt. Jimmy beat Ted Richards, and Ted beat the Ginger Nut, and the Ginger Nut only lost on a foul to Sid Simpson, and you beat Ted Richards, so they couldn’t help letting you have next go at Sid.”

Mr. Fisher beamed approval.

“If I’ve told your pa that once I’ve told him twenty times,” he said. “You certainly know a thing or two, Tommy.”

“Well, I’ve made a study of it since I was a kid, so I jolly well ought to. All the fellows at our place are frightfully keen on it. One chap’s got a snapshot of Freddy Welsh. At least, he says it’s Freddy Welsh, but I believe it’s just some ordinary fellow. Anyhow, it’s jolly blurred, so it might be anyone. Pa, can’t you give me a picture of yourself boxing? I could swank like anything. And you don’t know how sick a chap gets of having chaps call him ‘Goggles.’ ”

“Bill,” said Mr. Fisher, “you and me had better be getting back to the White Hart.”

Bill rose and followed him without a word.

Harold broke the silence which followed their departure. The animated expression which had been on his face as he discussed the relative merits of Sid Sampson and the Ginger Nut had given place to the abstracted gravity of the student.

“Ma!”

Mrs. Bramble started convulsively.

“Yes, dearie?”

“Will you hear me?”

Mrs. Bramble took the book.

“Yes, mother will hear you, precious,” she said, mechanically.

Harold fixed his eyes upon the cut-glass hangings of the chandelier.

“ ‘Be good, sweet maid, and let who will be clever’—clever. ‘Do noble things . . .’ ”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums