The Strand Magazine, March 1924

THERE was a sound of revelry by night, for the first Saturday in June had arrived and the Golf Club was holding its monthly dance. Fairy lanterns festooned the branches of the chestnut trees on the terrace above the ninth green, and from the big dining-room, cleared now of its tables and chairs, came a muffled slithering of feet and the plaintive sound of saxophones moaning softly like a man who has just missed a short putt. In a basket-chair in the shadows the Oldest Member puffed a cigar and listened, well content. His was the peace of the man who has reached the age when he is no longer expected to dance.

A door opened, and a young man came out of the club-house. He stood on the steps with folded arms, gazing to left and right. The Oldest Member, watching him from the darkness, noted that he wore an air of gloom. His brow was furrowed and he had the indefinable look of one who has been smitten in the spiritual solar plexus.

Yes, where all around him was joy, jollity, and song, this young man brooded.

The sound of a high tenor voice, talking rapidly and entertainingly on the subject of modern Russian thought, now intruded itself on the peace of the night. From the farther end of the terrace a girl came into the light of the lanterns, her arm in that of a second young man. She was small and pretty, he tall and intellectual. The light shone on his high forehead and glittered on his tortoiseshell-rimmed spectacles. The girl was gazing up at him with reverence and adoration, and at the sight of these twain the youth on the steps appeared to undergo some sort of spasm. His face became contorted and he wobbled. Then, with a gesture of sublime despair, he tripped over the mat and stumbled back into the club-house. The couple passed on and disappeared, and the Oldest Member had the night to himself, until the door opened once more and the club’s courteous and efficient secretary trotted down the steps. The scent of the cigar drew him to where the Oldest Member sat, and he dropped into the chair beside him.

“Seen young Ramage to-night?” asked the secretary.

“He was standing on those steps only a moment ago,” replied the Oldest Member. “Why do you ask?”

“I thought perhaps you might have had a talk with him and found out what’s the matter. Can’t think what’s come to him to-night. Nice, civil boy as a rule, but just now, when I was trying to tell him about my short approach on the fifth this afternoon, he was positively abrupt. Gave a sort of hollow gasp and dashed away in the middle of a sentence.”

The Oldest Member sighed.

“You must overlook his brusqueness,” he said. “The poor lad is passing through a trying time. A short while back I was the spectator of a little drama that explains everything. Mabel Patmore is flirting disgracefully with that young fellow Purvis.”

“Purvis? Oh, you mean the man who won the club Bowls Championship last week?”

“I can quite believe that he may have disgraced himself in the manner you describe,” said the Sage, coldly. “I know he plays that noxious game. And it is for that reason that I hate to see a nice girl like Mabel Patmore, who only needs a little more steadiness off the tee to become a very fair golfer, wasting her time on him. I suppose his attraction lies in the fact that he has a great flow of conversation, while poor Ramage is, one must admit, more or less of a dumb Isaac. Girls are too often snared by a glib tongue. Still, it is a pity, a great pity. The whole affair recalls irresistibly to my mind the story——”

The secretary rose with a whir like a rocketing pheasant.

“——the story,” continued the Sage, “of Jane Packard, William Bates, and Rodney Spelvin—which, as you have never heard it, I will now proceed to relate.”

“Can’t stop now, much as I should like——”

“It is a theory of mine,” proceeded the Oldest Member, attaching himself to the other’s coat-tails and pulling him gently back into his seat, “that nothing but misery can come of the union between a golfer and an outcast whose soul has not been purified by the noblest of games. This is well exemplified by the story of Jane Packard, William Bates, and Rodney Spelvin.”

“All sorts of things to look after——”

“That is why I am hoping so sincerely that there is nothing more serious than a temporary flirtation in this business of Mabel Patmore and bowls-playing Purvis. A girl in whose life golf has become a factor would be mad to trust her happiness to a blister whose idea of enjoyment is trundling wooden balls across a lawn. Sooner or later he is certain to fail her in some crisis. Lucky for her if this failure occurs before the marriage knot has been inextricably tied and so opens her eyes to his inadequacy—as was the case in the matter of Jane Packard, William Bates, and Rodney Spelvin. I will now,” said the Oldest Member, “tell you all about Jane Packard, William Bates, and Rodney Spelvin.”

The secretary uttered a choking groan.

“I shall miss the next dance,” he pleaded.

“A bit of luck for some nice girl,” said the Sage, equably.

He tightened his grip on the other’s arm.

JANE PACKARD and William Bates (said the Oldest Member) were not, you must understand, officially engaged. They had grown up together from childhood, and there existed between them a sort of understanding—the understanding being that, if ever William could speed himself up enough to propose, Jane would accept him, and they would settle down and live stodgily and happily ever after. For William was not one of your rapid wooers. In his affair of the heart he moved somewhat slowly and ponderously, like a motor-lorry, an object which both in physique and temperament he greatly resembled. He was an extraordinarily large, powerful, ox-like young man, who required plenty of time to make up his mind about any given problem. I have seen him in the club dining-room musing with a thoughtful frown for fifteen minutes on end while endeavouring to weigh the rival merits of a chump chop and a sirloin steak as a luncheon dish. A placid, leisurely man. I might almost call him lymphatic. I will call him lymphatic. He was lymphatic.

The first glimmering of an idea that Jane might possibly be a suitable wife for him had come to William some three years before this story opens. Having brooded on the matter tensely for six months, he then sent her a bunch of roses. In the October of the following year, nothing having occurred to alter his growing conviction that she was an attractive girl, he presented her with a two-pound box of assorted chocolates. And from then on his progress, though not rapid, was continuous, and there seemed little reason to doubt that, should nothing come about to weaken Jane’s regard for him, another five years or so would see the matter settled.

And it did not appear likely that anything would weaken Jane’s regard. They had much in common, for she was a calm, slow-moving person too. They had a mutual devotion to golf, and played together every day; and the fact that their handicaps were practically level formed a strong bond. Most divorces, as you know, spring from the fact that the husband is too markedly superior to his wife at golf; this leading him, when she starts criticizing his relations, to say bitter and unforgivable things about her mashie-shots. Nothing of this kind could happen with William and Jane. They would build their life on a solid foundation of sympathy and understanding. The years would find them consoling and encouraging each other, happy married lovers. If, that is to say, William ever got round to proposing.

It was not until the fourth year of this romance that I detected the first sign of any alteration in the schedule. I had happened to call on the Packards one afternoon and found them all out except Jane. She gave me tea and conversed for a while, but she seemed distrait. I had known her since she wore rompers, so felt entitled to ask if there was anything wrong.

“Not exactly wrong,” said Jane, and she heaved a sigh.

“Tell me,” I said.

She heaved another sigh.

“Have you ever read ‘The Love That Scorches,’ by Luella Periton Phipps?” she asked.

I said I had not.

“I got it out of the library yesterday,” said Jane, dreamily, “and finished it at three this morning in bed. It is a very, very beautiful book. It is all about the desert and people riding on camels and a wonderful Arab chief with stern yet tender eyes and a girl called Angela and oases and dates and mirages and all like that. There is a chapter where the Arab chief seizes the girl and clasps her in his arms and she feels his hot breath searing her face and he flings her on his horse and they ride off and all around was sand and night and the mysterious stars. And somehow—oh, I don’t know——”

She gazed yearningly at the chandelier.

“I wish mother would take me to Algiers next winter,” she murmured, absently. “It would do her rheumatism so much good.”

I went away frankly uneasy. These novelists, I felt, ought to be more careful. They put ideas into girls’ heads and made them dissatisfied. I determined to look William up and give him a kindly word of advice. It was no business of mine, you may say, but they were so ideally suited to one another that it seemed a tragedy that anything should come between them. And Jane was in a strange mood. At any moment, I felt, she might take a good, square look at William and wonder what she could ever have seen in him. I hurried to the boy’s cottage.

“William,” I said, “as one who dandled you on his knee when you were a baby, I wish to ask you a personal question. Answer me this, and make it snappy. Do you love Jane Packard?”

A look of surprise came into his face, followed by one of intense thought. He was silent for a space.

“Who, me?” he said at length.

“Yes, you.”

“Jane Packard?”

“Yes, Jane Packard.”

“Do I love Jane Packard?” said William, assembling the material and arranging it neatly in his mind.

He pondered for perhaps five minutes.

“Why, of course I do,” he said.

“Splendid!”

“Devotedly, dash it!”

“Capital!”

“You might say madly.”

I tapped him on his barrel-like chest.

“Then my advice to you, William Bates, is to tell her so.”

“Now that’s rather a brainy scheme,” said William, looking at me admiringly. “I see exactly what you’re driving at. You mean it would kind of settle things, and all that?”

“Precisely.”

“Well, I’ve got to go away for a couple of days to-morrow—it’s the Invitation Tournament at Squashy Hollow—but I’ll be back on Wednesday. Suppose I take her out on the links on Wednesday and propose?”

“A very good idea.”

“At the sixth hole, say?”

“At the sixth hole would do excellently.”

“Or the seventh?”

“The sixth would be better. The ground slopes from the tee, and you would be hidden from view by the dog-leg turn.”

“Something in that.”

“My own suggestion would be that you somehow contrive to lead her into that large bunker to the left of the seventh fairway.”

“Why?”

“I have reason to believe that Jane would respond more readily to your wooing were it conducted in some vast sandy waste. And there is another thing,” I proceeded, earnestly, “which I must impress upon you. See that there is nothing tame or tepid about your behaviour when you propose. You must show zip and romance. In fact, I strongly recommend you, before you even say a word to her, to seize her and clasp her in your arms and let your hot breath sear her face.”

“Who, me?” said William.

“Believe me, it is what will appeal to her most.”

“But, I say! Hot breath, I mean! Dash it all, you know, what?”

“I assure you it is indispensable.”

“Seize her?” said William, blankly.

“Precisely.”

“Clasp her in my arms?”

“Just so.”

William plunged into silent thought once more.

“Well, you know, I suppose,” he said at length. “You’ve had experience, I take it. Still—— Oh, all right, I’ll have a stab at it.”

“There spoke the true William Bates!” I said. “Go to it, lad, and Heaven speed your wooing!”

IN all human schemes—and it is this that so often brings failure to the subtlest strategists—there is always the chance of the Unknown Factor popping up, that unforeseen X for which we have made no allowance and which throws our whole plan of campaign out of gear. I had not anticipated anything of the kind coming along to mar the arrangements on the present occasion; but when I reached the first tee on the Wednesday afternoon to give William Bates that last word of encouragement which means so much, I saw that I had been too sanguine. William had not yet arrived, but Jane was there, and with her a tall, slim, dark-haired, sickeningly romantic-looking youth in faultlessly-fitting serge. A stranger to me. He was talking to her in a musical undertone, and she seemed to be hanging on his words. Her beautiful eyes were fixed on his face, and her lips slightly parted. So absorbed was she that it was not until I spoke that she became aware of my presence.

“William not arrived yet?”

She turned with a start.

“William? Hasn’t he? Oh! No, not yet. I don’t suppose he will be long. I want to introduce you to Mr. Spelvin. He has come to stay with the Wyndhams for a few weeks. He is going to walk round with us.”

Naturally this information came as a shock to me, but I masked my feelings and greeted the young man with a well-assumed cordiality.

“Mr. George Spelvin, the actor?” I asked, shaking hands.

“My cousin,” he said. “My name is Rodney Spelvin. I do not share George’s histrionic ambitions. If I have any claim to—may I say renown?—it is as a maker of harmonies.”

“A composer, eh?”

“Verbal harmonies,” explained Mr. Spelvin. “I am, in my humble fashion, a poet.”

“He writes the most beautiful poetry,” said Jane, warmly. “He has just been reciting some of it to me.”

“Oh, that little thing?” said Mr. Spelvin, deprecatingly. “A mere morceau. One of my juvenilia.”

“It was too beautiful for words,” persisted Jane.

“Ah, you,” said Mr. Spelvin, “have the soul to appreciate it. I could wish that there were more like you, Miss Packard. We singers have much to put up with in a crass and materialistic world. Only last week a man, a coarse editor, asked me what my sonnet, ‘Wine of Desire,’ meant.” He laughed indulgently. “I gave him answer, ’twas a sonnet, not a mining prospectus.”

“It would have served him right,” said Jane, heatedly, “if you had pasted him one on the snoot!”

At this point a low whistle behind me attracted my attention, and I turned to perceive William Bates towering against the sky-line.

“Hoy!” said William.

I walked to where he stood, leaving Jane and Mr. Spelvin in earnest conversation with their heads close together.

“I say,” said William, in a rumbling undertone, “who’s the bird with Jane?”

“A man named Spelvin. He is visiting the Wyndhams. I suppose Mrs. Wyndham made them acquainted.”

“Looks a bit of a Gawd-help-us,” said William, critically.

“He is going to walk round with you.”

It was impossible for a man of William Bates’s temperament to start, but his face took on a look of faint concern.

“Walk round with us?”

“So Jane said.”

“But look here,” said William. “I can’t possibly seize her and clasp her in my arms and do all that hot-breath stuff with this pie-faced exhibit hanging round on the outskirts.”

“No, I fear not.”

“Postpone it, then, what?” said William, with unmistakable relief. “Well, as a matter of fact, it’s probably a good thing. There was a most extraordinarily fine steak-and-kidney pudding at lunch, and, between ourselves, I’m not feeling what you might call keyed up to anything in the nature of a romantic scene. Some other time, eh?”

I looked at Jane and the Spelvin youth, and a nameless apprehension swept over me. There was something in their attitude which I found alarming. I was just about to whisper a warning to William not to treat this new arrival too lightly, when Jane caught sight of him and called him over, and a moment later they set out on their round.

I walked away pensively. This Spelvin’s advent, coming immediately on top of that book of desert love, was undeniably sinister. My heart sank for William, and I waited at the club-house to have a word with him after his match. He came in two hours later, flushed and jubilant.

“Played the game of my life!” he said. “We didn’t hole out all the putts, but, making allowance for everything, you can chalk me up an eighty-three. Not so bad, eh? You know the eighth hole? Well, I was a bit short with my drive, and found my ball lying badly for the brassy, so I took my driving-iron and with a nice easy swing let the pill have it so squarely on the seat of the pants that it flew——”

“Where is Jane?” I interrupted.

“Jane? Oh, the bloke Spelvin has taken her home.”

“Beware of him, William!” I whispered, tensely. “Have a care, young Bates! If you don’t look out, you’ll have him stealing Jane from you. Don’t laugh. Remember that I saw them together before you arrived. She was gazing into his eyes as a desert maiden might gaze into the eyes of a sheik. You don’t seem to realize, wretched William Bates, that Jane is an extremely romantic girl. A fascinating stranger like this, coming suddenly into her life, may well snatch her away from you before you know where you are.”

“That’s all right,” said William, lightly. “I don’t mind admitting that the same idea occurred to me. But I made judicious inquiries on the way round, and found out that the fellow’s a poet. You don’t seriously expect me to believe that there’s any chance of Jane falling in love with a poet?”

He spoke incredulously, for there were three things in the world that he held in the smallest esteem—slugs, poets, and caddies with hiccups.

“I think it extremely possible, if not probable,” I replied.

“Nonsense!” said William. “And, besides, the man doesn’t play golf. Never had a club in his hand, and says he never wants to. That’s the sort of fellow he is.”

At this, I confess, I did experience a distinct feeling of relief. I could imagine Jane Packard, stimulated by exotic literature, committing many follies, but I was compelled to own that I could not conceive of her giving her heart to one who not only did not play golf but had no desire to play it. Such a man, to a girl of her fine nature and correct upbringing, would be beyond the pale. I walked home with William in a calm and happy frame of mind.

I was to learn but one short week later that Woman is the unfathomable, incalculable mystery, the problem we men can never hope to solve.

THE week that followed was one of much festivity in our village. There were dances, picnics, bathing-parties, and all the other adjuncts of high summer. In these William Bates played but a minor part. Dancing was not one of his gifts. He swung, if called upon, an amiable shoe, but the disposition in the neighbourhood was to refrain from calling upon him; for he had an incurable habit of coming down with his full weight upon his partner’s toes, and many a fair girl had had to lie up for a couple of days after collaborating with him in a fox-trot.

Picnics, again, bored him, and he always preferred a round on the links to the merriest bathing-party. The consequence was that he kept practically aloof from the revels, and all through the week Jane Packard was squired by Rodney Spelvin. With Spelvin she swayed over the waxed floor; with Spelvin she dived and swam; and it was Spelvin who with zealous hand brushed ants off her mayonnaise and squashed wasps with a chivalrous teaspoon. The end was inevitable. Apart from anything else, the moon was at its full and many of these picnics were held at night. And you know what that means. It was about ten days later that William Bates came to me in my little garden with an expression on his face like a man who didn’t know it was loaded.

“I say,” said William, “you busy?”

I emptied the remainder of the water-can on the lobelias, and was at his disposal.

“I say,” said William, “rather a rotten thing has happened. You know Jane?”

I said I knew Jane.

“You know Spelvin?”

I said I knew Spelvin.

“Well, Jane’s gone and got engaged to him,” said William, aggrieved.

“What?”

“It’s a fact.”

“Already?”

“Absolutely. She told me this morning. And what I want to know,” said the stricken boy, sitting down thoroughly unnerved on a basket of strawberries, “is, where do I get off?”

My heart bled for him, but I could not help reminding him that I had anticipated this.

“You should not have left them so much alone together,” I said. “You must have known that there is nothing more conducive to love than the moon in June. Why, songs have been written about it. In fact, I cannot at the moment recall a song that has not been written about it.”

“Yes, but how was I to guess that anything like this would happen?” cried William, rising and scraping strawberries off his person. “Who would ever have supposed Jane Packard would leap off the dock with a fellow who doesn’t play golf?”

“Certainly, as you say, it seems almost incredible. You are sure you heard her correctly? When she told you about the engagement, I mean. There was no chance that you could have misunderstood?”

“Not a bit of it. As a matter of fact, what led up to the thing, if you know what I mean, was me proposing to her myself. I’d been thinking a lot during the last ten days over what you said to me about that, and the more I thought of it the more of a sound egg the notion seemed. So I got her alone up at the club-house and said, ‘I say, old girl, what about it?’ and she said, ‘What about what?’ and I said, ‘What about marrying me? Don’t if you don’t want to, of course,’ I said, ‘but I’m bound to say it looks pretty good to me.’ And then she said she loved another—this bloke Spelvin, to wit. A nasty jar, I can tell you, it was. I was just starting off on a round, and it made me hook my putts on every green.”

“But did she say specifically that she was engaged to Spelvin?”

“She said she loved him.”

“There may be hope. If she is not irrevocably engaged the fancy may pass. I think I will go and see Jane and make tactful inquiries.”

“I wish you would,” said William. “And, I say, you haven’t any stuff that’ll take strawberry-juice off a fellow’s trousers, have you?”

MY interview with Jane that evening served only to confirm the bad news. Yes, she was definitely engaged to the man Spelvin. In a burst of girlish confidence she told me some of the details of the affair.

“The moon was shining and a soft breeze played in the trees,” she said. “And suddenly he took me in his arms, gazed deep into my eyes, and cried, ‘I love you! I worship you! I adore you! You are the tree on which the fruit of my life hangs; my mate; my woman; predestined to me since the first star shone up in yonder sky!’ ”

“Nothing,” I agreed, “could be fairer than that. And then?” I said, thinking how different it all must have been from William Bates’s miserable, limping proposal.

“Then we fixed it up that we would get married in September.”

“You are sure you are doing wisely?” I ventured.

Her eyes opened.

“Why do you say that?”

“Well, you know, whatever his other merits—and no doubt they are numerous—Rodney Spelvin does not play golf.”

“No, but he’s very broad-minded about it.”

I shuddered. Women say these things so lightly.

“Broad-minded?”

“Yes. He has no objection to my going on playing. He says he likes my pretty enthusiasms.”

There seemed nothing more to say on that subject.

“Well,” I said, “I am sure I wish you every happiness. I had hoped, of course—but never mind that.”

“What?”

“I had hoped, as you insist on my saying it, that you and William Bates——”

A shadow passed over her face. Her eyes grew sad.

“Poor William! I’m awfully sorry about that. He’s a dear.”

“A splendid fellow,” I agreed.

“He has been so wonderful about the whole thing. So many men would have gone off and shot grizzly bears or something. But William just said ‘Right-o!’ in a quiet voice, and he’s going to caddy for me at Mossy Heath next week.”

“There is good stuff in the boy.”

“Yes.” She sighed. “If it wasn’t for Rodney—— Oh, well!”

I thought it would be tactful to change the subject.

“So you have decided to go to Mossy Heath again?”

“Yes. And I’m really going to qualify this year.”

THE annual Invitation Tournament at Mossy Heath was one of the most important fixtures of our local female golfing year. As is usual with these affairs, it began with a medal-play qualifying round, the thirty-two players with the lowest net scores then proceeding to fight it out during the remainder of the week by match-play. It gratified me to hear Jane speak so confidently of her chances, for this was the fourth year she had entered, and each time, though she had started out with the brightest prospects, she had failed to survive the qualifying round. Like so many golfers, she was fifty per cent. better at match-play than at medal-play. Mossy Heath, being a championship course, is full of nasty pitfalls, and on each of the three occasions on which she had tackled it one very bad hole had undone all her steady work on the other seventeen and ruined her card. I was delighted to find her so undismayed by failure.

“I am sure you will,” I said. “Just play your usual careful game.”

“It doesn’t matter what sort of a game I play this time,” said Jane, jubilantly. “I’ve just heard that there are only thirty-two entries this year, so that everybody who finishes is bound to qualify. I have simply got to get round somehow, and there I am.”

“It would seem somewhat superfluous in these circumstances to play a qualifying round at all.”

“Oh, but they must. You see, there are prizes for the best three scores, so they have to play it. But isn’t it a relief to know that, even if I come to grief on that beastly seventh, as I did last year, I shall still be all right?”

“It is, indeed. I have a feeling that once it becomes a matter of match-play you will be irresistible.”

“I do hope so. It would be lovely to win with Rodney looking on.”

“Will he be looking on?”

“Yes. He’s going to walk round with me. Isn’t it sweet of him?”

Her fiancé’s name having slid into the conversation again, she seemed inclined to become eloquent about him. I left her, however, before she could begin. To one so strongly pro-William as myself, eulogistic prattle about Rodney Spelvin was repugnant. I disapproved entirely of this infatuation of hers. I am not a narrow-minded man; I quite appreciate the fact that non-golfers are entitled to marry; but I could not countenance their marrying potential winners of the Ladies’ Invitation Tournament at Mossy Heath.

The Greens Committee, as greens committees are so apt to do in order to justify their existence, have altered the Mossy Heath course considerably since the time of which I am speaking, but they have left the three most poisonous holes untouched. I refer to the fourth, the seventh, and the fifteenth. Even a soulless Greens Committee seems to have realized that golfers, long-suffering though they are, can be pushed too far, and that the addition of even a single extra bunker to any of these dreadful places would probably lead to armed riots in the club-house.

Jane Packard had done well on the first three holes, but as she stood on the fourth tee she was conscious, despite the fact that this seemed to be one of her good days, of a certain nervousness; and oddly enough, great as was her love for Rodney Spelvin, it was not his presence that gave her courage, but the sight of William Bates’s large, friendly face and the sound of his pleasant voice urging her to keep her bean down and refrain from pressing.

As a matter of fact, to be perfectly truthful, there was beginning already to germinate within her by this time a faint but definite regret that Rodney Spelvin had decided to accompany her on this qualifying round. It was sweet of him to bother to come, no doubt, but still there was something about Rodney that did not seem to blend with the holy atmosphere of a championship course. He was the one romance of her life and their souls were bound together for all eternity, but the fact remained that he did not appear to be able to keep still while she was making her shots, and his light humming, musical though it was, militated against accuracy on the green. He was humming now as she addressed her ball, and for an instant a spasm of irritation shot through her. She fought it down bravely and concentrated on her drive, and when the ball soared over the cross-bunker she forgot her annoyance. There is nothing so mellowing, so conducive to sweet and genial thoughts, as a real juicy one straight down the middle, and this was a pipterino.

“Nice work,” said William Bates, approvingly.

Jane gave him a grateful smile and turned to Rodney. It was his appreciation that she wanted. He was not a golfer, but even he must be able to see that her drive had been something out of the common.

Rodney Spelvin was standing with his back turned, gazing out over the rolling prospect, one hand shading his eyes.

“That vista there,” said Rodney. “That calm, wooded hollow bathed in the golden sunshine. It reminds me of the island valley of Avilion——”

“Did you see my drive, Rodney?”

“——where falls not rain nor hail nor any snow, nor ever wind blows loudly. Eh? Your drive? No, I didn’t.”

Again Jane Packard was aware of that faint, wistful regret. But this was swept away a few moments later in the ecstasy of a perfect iron-shot which plunked her ball nicely on to the green. The last time she had played this hole she had taken seven, for all round the plateau green are sinister sand-bunkers, each beckoning the ball into its hideous depths; and now she was on in two and life was very sweet. Putting was her strong point, so that there was no reason why she should not get a snappy four on one of the nastiest holes on the course. She glowed with a strange emotion as she took her putter, and as she bent over her ball the air seemed filled with soft music.

It was only when she started to concentrate on the line of her putt that this soft music began to bother her. Then, listening, she became aware that it proceeded from Rodney Spelvin. He was standing immediately behind her, humming an old French love-song. It was the sort of old French love-song to which she could have listened for hours in some scented garden under the young May moon, but on the green of the fourth at Mossy Heath it got right in amongst her nerve-centres.

“Rodney, please!”

“Eh?”

Jane found herself wishing that Rodney Spelvin would not say “Eh?” whenever she spoke to him.

“Do you mind not humming?” said Jane. “I want to putt.”

“Putt on, child, putt on,” said Rodney Spelvin, indulgently. “I don’t know what you mean, but, if it makes you happy to putt, putt to your heart’s content.”

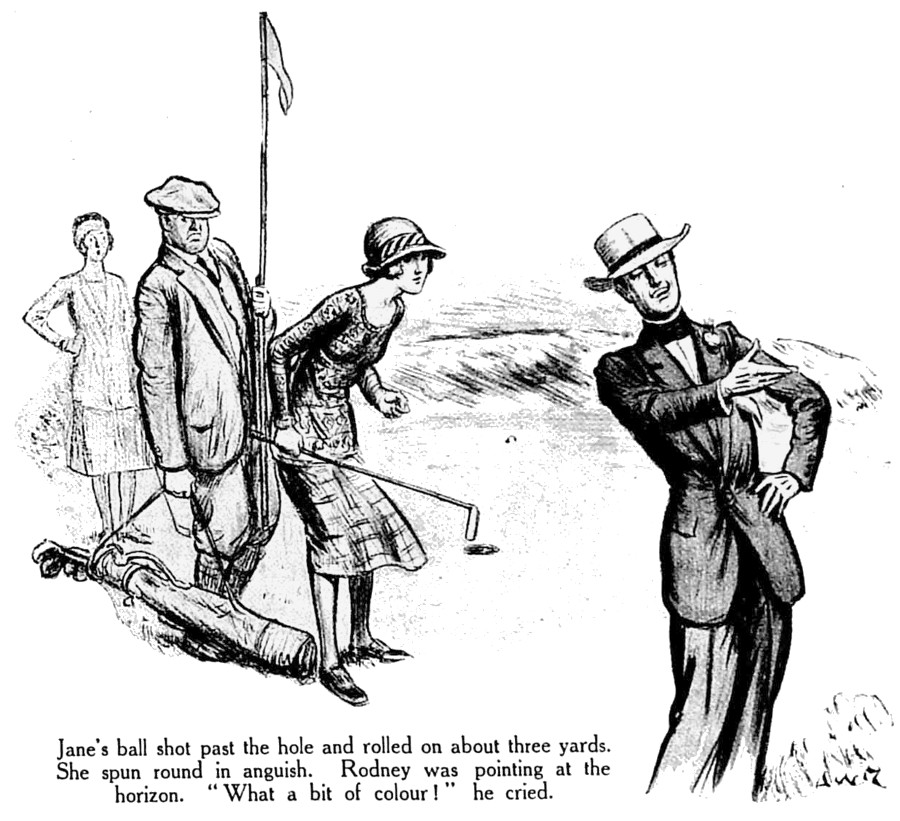

Jane bent over her ball again. She had got the line now. She brought back her putter with infinite care.

“My God!” exclaimed Rodney Spelvin, going off like a bomb.

Jane’s ball, sharply jabbed, shot past the hole and rolled on about three yards. She spun round in anguish. Rodney Spelvin was pointing at the horizon.

“What a bit of colour!” he cried. “Did you ever see such a bit of colour?”

“Oh, Rodney!” moaned Jane.

“Eh?”

Jane gulped and walked to her ball. Her fourth putt trickled into the hole.

“Did you win?” said Rodney Spelvin, amiably.

Jane walked to the fifth tee in silence.

THE fifth and sixth holes at Mossy Heath are long, but they offer little trouble to those who are able to keep straight. It is as if the architect of the course had relaxed over these two in order to ensure that his malignant mind should be at its freshest and keenest when he came to design the pestilential seventh. This seventh, as you may remember, is the hole at which Sandy McHoots, then Open Champion, took an eleven on an important occasion. It is a short hole, and a full mashie will take you nicely on to the green, provided you can carry the river that frolics just beyond the tee and seems to plead with you to throw it a ball to play with. Once on the green, however, the problem is to stay there. The green itself is about the size of a drawing-room carpet, and in the summer, when the ground is hard, a ball that has not the maximum of back-spin is apt to touch lightly and bound off into the river beyond; for this is an island green, where the stream bends like a serpent. I refresh your memory with these facts in order that you may appreciate to the full what Jane Packard was up against.

The woman with whom Jane was partnered had the honour, and drove a nice high ball which fell into one of the bunkers to the left. She was a silent, patient-looking woman, and she seemed to regard this as perfectly satisfactory. She withdrew from the tee and made way for Jane.

“Nice work!” said William Bates, a moment later. For Jane’s ball, soaring in a perfect arc, was dropping, it seemed, on the very pin.

“Oh, Rodney, look!” cried Jane.

“Eh?” said Rodney Spelvin.

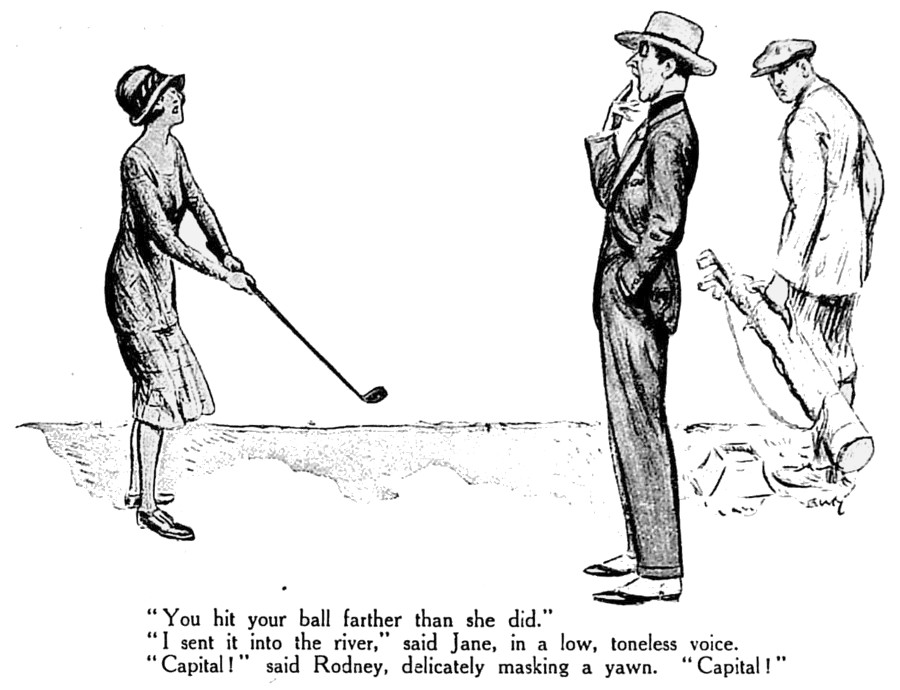

His remark was drowned in a passionate squeal of agony from his betrothed. The most poignant of all tragedies had occurred. The ball, touching the green, leaped like a young lamb, scuttled past the pin, and took a running dive over the cliff.

There was a silence. Jane’s partner, who was seated on the bench by the sand-box reading a pocket edition in limp leather of Vardon’s “What Every Young Golfer Should Know,” with which she had been refreshing herself at odd moments all through the round, had not observed the incident. William Bates, with the tact of a true golfer, refrained from comment. Jane was herself swallowing painfully. It was left to Rodney Spelvin to break the silence.

“Good!” he said.

Jane Packard turned like a stepped-on worm.

“What do you mean, good?”

“You hit your ball farther than she did.”

“I sent it into the river,” said Jane, in a low, toneless voice.

“Capital!” said Rodney Spelvin, delicately masking a yawn with two fingers of his shapely right hand. “Capital! Capital!”

Her face contorted with pain, Jane put down another ball.

“Playing three,” she said.

The student of Vardon marked the place in her book with her thumb, looked up, nodded, and resumed her reading.

“Nice w——” began William Bates, as the ball soared off the tee, and checked himself abruptly. Already he could see that the unfortunate girl had put too little beef into it. The ball was falling, falling. It fell. A crystal fountain flashed up towards the sun. The ball lay floating on the bosom of the stream, only some few feet short of the island. But, as has been well pointed out, that little less and how far away!

“Playing five!” said Jane, between her teeth.

“What,” inquired Rodney Spelvin, chattily, lighting a cigarette, “is the record break?”

“Playing five,” said Jane, with a dreadful calm, and gripped her mashie.

“Half a second,” said William Bates, suddenly. “I say, I believe you could play that last one from where it floats. A good crisp slosh with a niblick would put you on, and you’d be there in four, with a chance for a five. Worth trying, what? I mean, no sense in dropping strokes unless you have to.”

Jane’s eyes were gleaming. She threw William a look of infinite gratitude.

“Why, I believe I could!”

“Worth having a dash.”

“There’s a boat down there!”

“I could row,” said William.

“I could stand in the middle and slosh,” cried Jane.

“And what’s-his-name—that,” said William, jerking his head in the direction of Rodney Spelvin, who was strolling up and down behind the tee, humming a gay Venetian barcarolle, “could steer.”

“William,” said Jane, fervently, “you’re a darling.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said William, modestly.

“There’s no one like you in the world. Rodney!”

“Eh?” said Rodney Spelvin.

“We’re going out in that boat. I want you to steer.”

Rodney Spelvin’s face showed appreciation of the change of programme. Golf bored him, but what could be nicer than a gentle row in a boat?

“Capital!” he said. “Capital! Capital!”

There was a dreamy look in Rodney Spelvin’s eyes as he leaned back with the tiller-ropes in his hands. This was just his idea of the proper way of passing a summer afternoon. Drifting lazily over the silver surface of the stream. His eyes closed. He began to murmur softly.

“All to-day the slow sleek ripples hardly bear up shoreward, Charged with sighs more light than laughter, faint and fair, Like a woodland lake’s weak wavelets lightly lingering forward, Soft and listless as the—— Here! Hi!”

For at this moment the silver surface of the stream was violently split by a vigorously-wielded niblick, the boat lurched drunkenly, and over his Panama-hatted head and down his grey-flannelled torso there descended a cascade of water.

“Here! Hi!” cried Rodney Spelvin.

He cleared his eyes and gazed reproachfully. Jane and William Bates were peering into the depths.

“I missed it,” said Jane.

“There she spouts!” said William, pointing. “Ready?”

Jane raised her niblick.

“Here! Hi!” bleated Rodney Spelvin, as a second cascade poured damply over him.

He shook the drops off his face, and perceived that Jane was regarding him with hostility.

“I do wish you wouldn’t talk just as I am swinging,” she said, pettishly. “Now you’ve made me miss it again! If you can’t keep quiet, I wish you wouldn’t insist on coming round with one. Can you see it, William?”

“There she blows,” said William Bates.

“Here! You aren’t going to do it again, are you?” cried Rodney Spelvin.

Jane bared her teeth.

“I’m going to get that ball on to the green if I have to stay here all night,” she said.

Rodney Spelvin looked at her and shuddered. Was this the quiet, dreamy girl he had loved? This Mænad? Her hair was lying in damp wisps about her face, her eyes were shining with an unearthly light.

“No, but really——” he faltered.

Jane stamped her foot.

“What are you making all this fuss about, Rodney?” she snapped. “Where is it, William?”

“There she dips,” said William, “Playing six.”

“Playing six.”

“Let her go!” said William.

“Let her go it is!” said Jane.

A perfect understanding seemed to prevail between these two.

Splash!

The woman on the bank looked up from her Vardon as Rodney Spelvin’s agonized scream rent the air. She saw a boat upon the water, a man rowing the boat, another man, hatless, gesticulating in the stern, a girl beating the water with a niblick. She nodded placidly and understandingly. A niblick was the club she would have used herself in such circumstances. Everything appeared to her entirely regular and orthodox. She resumed her book.

Splash!

“Playing fifteen,” said Jane.

“Fifteen is right,” said William Bates.

Splash! Splash! Splash!

“Playing forty-four.”

“Forty-four is correct.”

Splash! Splash! Splash! Splash!

“Eighty-three?” said Jane, brushing the hair out of her eyes.

“No. Only eighty-two,” said William Bates.

“Where is it?”

“There she drifts.”

A dripping figure rose violently in the stern of the boat, spouting water like a public fountain. For what seemed to him like an eternity Rodney Spelvin had ducked and spluttered and writhed, and now it came to him abruptly that he was through. He bounded from his seat, and at the same time Jane swung with all the force of her supple body. There was a splash beside which all the other splashes had been as nothing. The boat overturned and went drifting away. Three bodies plunged into the stream. Three heads emerged from the water.

The woman on the bank looked absently in their direction. Then she resumed her book.

“It’s all right,” said William Bates, contentedly. “We’re in our depth.”

“My bag!” cried Jane. “My bag of clubs!”

“Must have sunk,” said William.

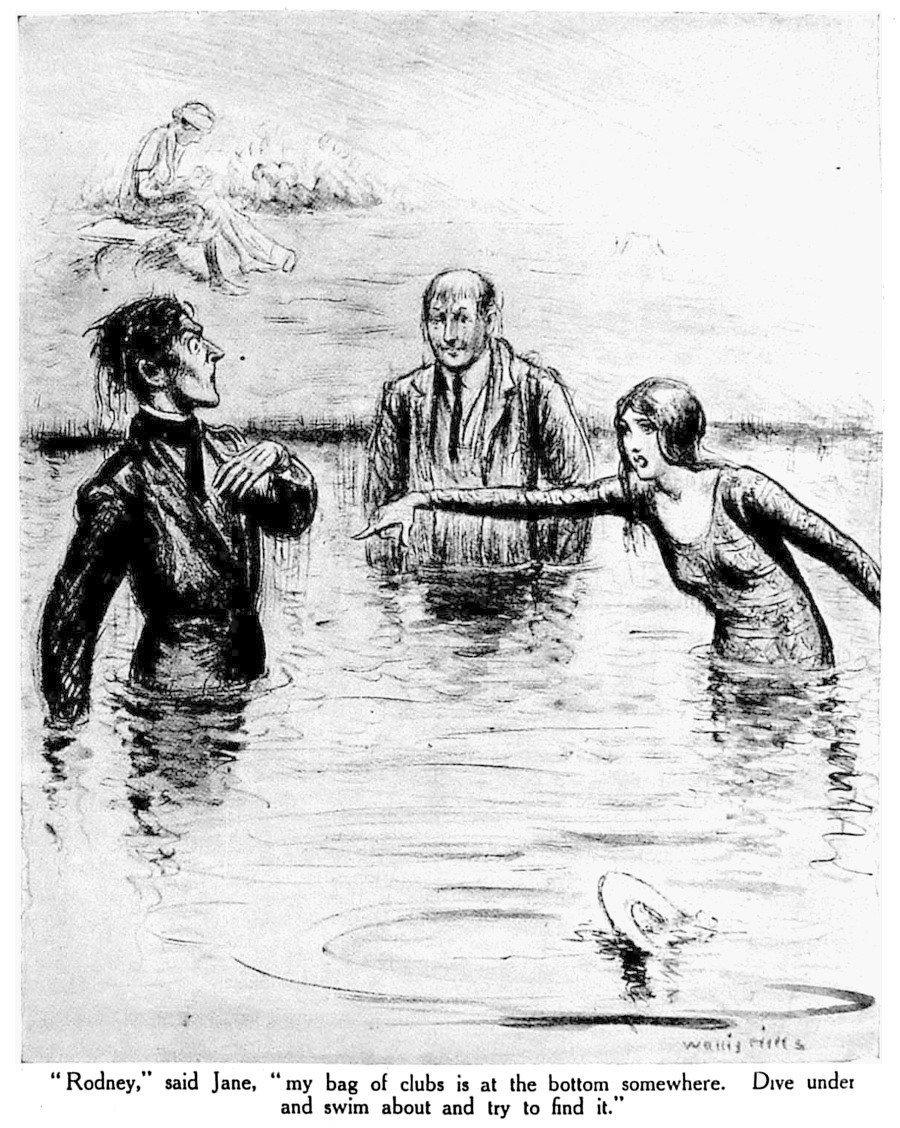

“Rodney,” said Jane, “my bag of clubs is at the bottom somewhere. Dive under and swim about and try to find it.”

“It’s bound to be around somewhere,” said William Bates, encouragingly.

Rodney Spelvin drew himself up to his full height. It was not an easy thing to do, for it was muddy where he stood, but he did it.

“Damn your bag of clubs!” he bellowed, lost to all shame. “I’m going home!”

With painful steps, tripping from time to time and vanishing beneath the surface, he sloshed to the shore. For a moment he paused on the bank, silhouetted against the summer sky, then he was gone.

JANE PACKARD and William Bates watched him go with amazed eyes.

“I never would have dreamed,” said Jane, dazedly, “that he was that sort of man.”

“A bad lot,” said William Bates.

“The sort of man to be upset by the merest trifle!”

“Must have a naturally bad disposition,” said William Bates.

“Why, if a little thing like this could make him so rude and brutal and horrid, it wouldn’t be safe to marry him!”

“Taking a big chance,” agreed William Bates. “Sort of fellow who would poison the cat’s milk and kick the baby in the face.” He took a deep breath and disappeared. “Here are your clubs, old girl,” he said, coming to the surface again. “Only wanted a bit of looking for.”

“Oh, William,” said Jane, “you are the most wonderful man on earth!”

“Would you go so far as that?” said William.

“I was mad, mad, ever to get engaged to that brute!”

“Now there,” said William Bates, removing an eel from his left breast-pocket, “I’m absolutely with you. Thought so all along, but didn’t like to say so. What I mean is, a girl like you—keen on golf and all that sort of thing—ought to marry a chap like me—keen on golf and everything of that description.”

“William,” cried Jane, passionately, detaching a newt from her right ear, “I will!”

“Silly nonsense, when you come right down to it, your marrying a fellow who doesn’t play golf. Nothing in it.”

“I’ll break off the engagement the moment I get home.”

“You couldn’t make a sounder move, old girl.”

“William!”

“Jane!”

The woman on the bank, glancing up as she turned a page, saw a man and a girl embracing, up to their waists in water. It seemed to have nothing to do with her. She resumed her book.

Jane looked lovingly into William’s eyes.

“William,” she said, “I think I have loved you all my life.”

“Jane,” said William, “I’m dashed sure I’ve loved you all my life. Meant to tell you so a dozen times, but something always seemed to come up.”

“William,” said Jane, “you’re an angel and a darling. Where’s the ball?”

“There she pops.”

“Playing eighty-four?”

“Eighty-four it is,” said William. “Slow back, keep your eye on the ball, and don’t press.”

The woman on the bank began Chapter Twenty-five.

(Another P. G. Wodehouse story next month.)

Notes:

Compare the American magazine version of the story from the Saturday Evening Post, February 23, 1924.

For explanations of the following terms of golfing jargon, see A Glossary of Golf Terminology on this site: address, approach, brassy, bunker, caddy, card, club, committee, dog-leg, drive, fairway, green, hole out, honour, hook, iron, links, mashie, match play, medal play, niblick, press, putt, round, stroke, tee.

There was a sound of revelry by night: Opening line of Lord Byron’s “Waterloo”, a section of the longer Childe Harold, canto iii, stanzas 21–30.

basket-chair: a chair formed by weaving stiff woody materials such as wicker or rattan.

solar plexus: a concentration of nerve cells located under the diaphragm and behind the stomach, which controls the functioning of the digestive system. Loosely it is used to refer to the stomach area when talking about painful blows. [Note by Mark Hodson]

joy, jollity, and song: Norman Murphy could not locate the original source, but noted in A Wodehouse Handbook that Wodehouse jotted it down in 1905 in his Phrases and Notes notebook, and used it frequently, from Psmith in the City onward.

Bowls: lawn bowling.

chump chop: a lamb chop cut from the rump of the lamb.

lymphatic: From the ancient theory of humours (bodily fluids affecting the temperament), a sluggishness of mental action supposed to result from having too much lymph in the body.

rompers: children’s play clothes, typically in one piece combining a shirt with shorts or longer trousers.

“The Love that Scorches”: A takeoff on the desert romance genre typified by E. M. Hull’s The Sheik (1919), which contains such phrases as “His hot breath was on her face” and “flung a pair of powerful arms around her, and,

with a jerk, swung her clear of the saddle and on to his own horse in

front of him.”

zip: From the sound of a bullet tearing through the air, the figurative use of “zip” for energy or force has OED citations dating back only to 1900.

sanguine: Also from the theory of humours, an optimistic and courageous tendency, thought to result from the predominant influence of the blood.

George Spelvin, the actor: A traditional theatrical pseudonym, used in publicity and cast lists when an actor for contractual reasons cannot appear under his own name, or to avoid forewarning the audience when two roles are played by the same actor.

pill: the golf ball.

an amiable shoe … a chivalrous teaspoon: Examples of a transferred epithet, one of Wodehouse’s favorite rhetorical devices. See the notes to Right Ho, Jeeves for more.

the tree on which the fruit of my life hangs: An echo of W. S. Gilbert’s play Engaged, in which Cheviot Hill has a recurring line referring to various women as “the tree upon which the fruit of my heart is growing.” See Arthur Robinson’s Wodehouse-Gilbert page on this site for many other Wodehouse uses of this allusion.

my mate: An essential part of the Ickenham System of wooing; see Uncle Dynamite (1948), Cocktail Time (1958), Service With a Smile (1961), etc.

shot grizzly bears: This distraction for disappointed lovers is mentioned often in Wodehouse, including in Three Men and a Maid and in Ice in the Bedroom.

pipterino: This name for someone or something very special seems to be a Wodehouse coinage, an intensive version of “pip” or “pippin” for something choice. The word has not yet made it into the OED. Wodehouse uses it of a waltz in The Little Warrior, of a golf drive here, of a wifely telegram in Full Moon, and most famously in Bertie Wooster’s speech for a very pretty girl, e.g. Daphne Dolores Morehead in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, “a pipterino of the first water,” as is Phyllis Mills in Jeeves in the Offing.

island valley of Avilion: See the notes to Something Fishy.

Vardon’s “What Every Young Golfer Should Know”: The book is a Wodehouse invention, the title a parody of William J. Fielding’s 1924 sex-education volumes “What Every Young Man Should Know” and “What Every Young Woman Should Know.” But Wodehouse attributes the golf manual to a real golfer and author, Harry Vardon (1870–1937), six-time winner of the British Open.

All to-day the slow sleek ripples…: An excerpt from “A Word With the Wind” by Algernon Charles Swinburne.

Mænad: in Greek mythology, the female followers of Dionysus, possessed by the god as they performed frenzied, ecstatic dances; the name Maenads means “raving ones” in literal translation.

shining with an unearthly light: This phrase appears frequently in religious contexts, for example describing the face of Moses or Jesus; it is rarer but not unknown in secular fiction.

in our depth: in water shallow enough that standing on the bottom, one’s head is above the surface.

—Notes by Neil Midkiff and others as noted

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums