The Strand Magazine, October 1924

“ JEEVES,” I said, emerging from the old tub, “rally round.”

“Yes, sir.”

I beamed on the man with no little geniality. I was putting in a week or two in Paris at the moment, and there’s something about Paris that always makes me feel fairly full of espièglerie and joie de vivre.

“Lay out our gent’s medium-smart raiment, suitable for Bohemian revels,” I said. “I am lunching with an artist bloke on the other side of the river.”

“Very good, sir.”

“And if anybody calls for me, Jeeves, say that I shall be back towards the quiet evenfall.”

“Yes, sir. Mr. Biffen rang up on the telephone while you were in your bath.”

“Mr. Biffen? Good heavens!”

Amazing how one’s always running across fellows in foreign cities—birds, I mean, whom you haven’t seen for ages and would have betted weren’t anywhere in the neighbourhood. Paris was the last place where I should have expected to find old Biffy popping up. There was a time when he and I had been lads about town together, lunching and dining together practically every day; but some eighteen months back his old godmother had died and left him that place in Herefordshire, and he had retired there to wear gaiters and prod cows in the ribs and generally be the country gentleman and landed proprietor. Since then I had hardly seen him.

“Old Biffy in Paris? What’s he doing here?”

“He did not confide in me, sir,” said Jeeves—a trifle frostily, I thought. It sounded somehow as if he didn’t like Biffy. And yet they had always been matey enough in the old days.

“He did not confide in me, sir,” said Jeeves—a trifle frostily, I thought. It sounded somehow as if he didn’t like Biffy. And yet they had always been matey enough in the old days.

“Where’s he staying?”

“At the Hotel Avenida, Rue du Colisée, sir. He informed me that he was about to take a walk and would call this afternoon.”

“Well, if he comes when I’m out, tell him to wait. And now, Jeeves, mes gants, mon chapeau, et le whangee de monsieur. I must be popping.”

It was such a corking day and I had so much time in hand that near the Sorbonne I stopped my cab, deciding to walk the rest of the way. And I had hardly gone three steps and a half when there on the pavement before me stood old Biffy in person. If I had completed the last step I should have rammed him.

“Biffy!” I cried. “Well, well, well!”

He peered at me in a blinking kind of way, rather like one of his Herefordshire cows prodded unexpectedly while lunching.

“Bertie!” he gurgled, in a devout sort of tone. “Thank God!” He clutched my arm. “Don’t leave me, Bertie. I’m lost.”

“What do you mean, lost?”

“I came out for a walk and suddenly discovered after a mile or two that I didn’t know where on earth I was. I’ve been wandering round in circles for hours.”

“Why didn’t you ask the way?”

“I can’t speak a word of French.”

“Well, why didn’t you call a taxi?”

“I suddenly discovered I’d left all my money at my hotel.”

“You could have taken a cab and paid it when you got to the hotel.”

“Yes, but suddenly I discovered, dash it, that I’d forgotten its name.”

And there in a nutshell you have Charles Edward Biffen. As vague and woolen-headed a blighter as ever bit a sandwich. Goodness knows—and my Aunt Agatha will bear me out in this—I’m no master-mind myself; but compared with Biffy I’m one of the great thinkers of all time.

“I’d give a shilling,” said Biffy, wistfully, “to know the name of that hotel.”

“You can owe it me. Hotel Avenida, Rue du Colisée.”

“Bertie! This is uncanny. How the deuce did you know?”

“That was the address you left with Jeeves this morning.”

“So it was. I had forgotten.”

“Well, come along and have a drink, and then I’ll put you in a cab and send you home. I’m engaged for lunch, but I’ve plenty of time.”

We drifted to one of the eleven cafés which jostled each other along the street and I ordered restoratives.

“What on earth are you doing in Paris?” I asked.

“Bertie, old man,” said Biffy, solemnly, “I came here to try and forget.”

“Well, you’ve certainly succeeded.”

“You don’t understand. The fact is, Bertie, old lad, my heart is broken. I’ll tell you the whole story.”

“No, I say!” I protested. But he was off.

“Last year,” said Biffy, “I buzzed over to Canada to do a bit of salmon fishing.”

I ordered another. If this was going to be a fish-story, I needed stimulants.

“On the liner going to New York I met a girl.” Biffy made a sort of curious gulping noise not unlike a bulldog trying to swallow half a cutlet in a hurry so as to be ready for the other half. “Bertie, old man, I can’t describe her. I simply can’t describe her.”

THIS was all to the good.

“She was wonderful! We used to walk on the boat-deck after dinner. She was on the stage. At least, sort of.”

“How do you mean, sort of?”

“Well, she had worked with a concert party and posed for artists and been a mannequin in a big dressmaker’s and all that sort of thing, don’t you know,” said Biffy, vaguely. “Anyway, she had saved up a few pounds and was on her way to see if she could get a job in New York. She told me all about herself. Her father ran a milk-walk in Clapham. Or it may have been Cricklewood. At least, it was either a milk-walk or a boot-shop.”

“Easily confused.”

“What I’m trying to make you understand,” said Biffy, “is that she came of good, sturdy, respectable middle-class stock. Nothing flashy about her. The sort of wife any man might have been proud of.”

“Well, whose wife was she?”

“Nobody’s. That’s the whole point of the story. I wanted her to be mine, and I lost her.”

“Had a quarrel, you mean?”

“No, I don’t mean we had a quarrel. I mean I literally lost her. The last I ever saw of her was in the Customs sheds at New York. We were behind a pile of trunks, and I had just asked her to be my wife, and she had just said she would and everything was perfectly splendid, when a most offensive blighter in a peaked cap came up to talk about some cigarettes which he had found at the bottom of my trunk and which I had forgotten to declare. It was getting pretty late by then, for we hadn’t docked till about ten-thirty, so I told Mabel to go on to her hotel and I would come round next day and take her to lunch. And since then I haven’t set eyes on her.”

“You mean she wasn’t at the hotel?”

“Probably she was. But——”

“You don’t mean you never turned up?”

“Bertie, old man,” said Biffy, in an overwrought kind of way, “for Heaven’s sake don’t keep trying to tell me what I mean and what I don’t mean! Let me tell this my own way, or I shall get all mixed up and have to go back to the beginning.”

“Tell it your own way,” I said, hastily.

“Well, then, to put it in a word, Bertie, I forgot the name of the hotel. By the time I’d done half an hour’s heavy explaining about those cigarettes my mind was a blank. I had an idea I had written the name down somewhere, but I couldn’t have done, for it wasn’t on any of the papers in my pocket. No, it was no good. She was gone.”

“Why didn’t you make inquiries?”

“Well, the fact is, Bertie, I had forgotten her name.”

“Oh, no, dash it!” I said. This seemed a bit too thick even for Biffy. “How could you forget her name? Besides, you told it me a moment ago. Muriel or something.”

“Mabel,” corrected Biffy, coldly. “It was her surname I’d forgotten. So I gave it up and went to Canada.”

“But half a second,” I said. “You must have told her your name. I mean, if you couldn’t trace her, she could trace you.”

“Exactly. That’s what makes it all seem so infernally hopeless. She knows my name and where I live and everything, but I haven’t heard a word from her. I suppose, when I didn’t turn up at the hotel, she took it that that was my way of hinting delicately that I had changed my mind and wanted to call the thing off.”

“I suppose so,” I said. There didn’t seem anything else to suppose. “Well, the only thing to do is to whizz around and try to heal the wound, what? How about dinner to-night, winding up at the Abbaye, or one of those places?”

Biffy shook his head.

“It wouldn’t be any good. I’ve tried it. Besides, I’m leaving on the four o’clock train. I have a dinner engagement to-morrow with a man who’s nibbling at that house of mine in Herefordshire.”

“Oh, are you trying to sell that place? I thought you liked it.”

“I did. But the idea of going on living in that great, lonely barn of a house after what has happened appals me, Bertie. So when Sir Roderick Glossop came along——”

“Sir Roderick Glossop! You don’t mean the loony-doctor?”

“The great nerve specialist, yes. Why, do you know him?”

It was a warm day, but I shivered.

“I was engaged to his daughter for a week or two,” I said, in a hushed voice. The memory of that narrow squeak always made me feel faint.

“Has he a daughter?” said Biffy, absently.

“He has. Let me tell you all about——”

“Not just now, old man,” said Biffy, getting up. “I ought to be going back to my hotel to see about my packing.”

Which, after I had listened to his story, struck me as pretty low-down. However, the longer you live, the more you realize that the good old sporting spirit of give-and-take has practically died out in our midst. So I boosted him into a cab and went off to lunch.

IT can’t have been more than ten days after this that I received a nasty shock while getting outside my morning tea and toast. The English papers had arrived, and Jeeves was just drifting out of the room after depositing The Times by my bedside, when, as I idly turned the pages in search of the sporting section, a paragraph leaped out and hit me squarely in the eyeball.

As follows:—

FORTHCOMING MARRIAGES.

Mr. C. E. Biffen and Miss Glossop.

The engagement is announced between Charles Edward, only son of the late Mr. E. C. Biffen, and Mrs. Biffen, of 11, Penslow Square, Mayfair, and Honoria Jane Louise, only daughter of Sir Roderick and Lady Glossop, of 6b, Harley Street, W.

“Great Scott!” I exclaimed.

“Sir?” said Jeeves, turning at the door.

“Jeeves, you remember Miss Glossop?”

“Very vividly, sir.”

“She’s engaged to Mr. Biffen!”

“Indeed, sir?” said Jeeves. And, with not another word, he slid out. The blighter’s calm amazed and shocked me. It seemed to indicate that there must be a horrible streak of callousness in him. I mean to say, it wasn’t as if he didn’t know Honoria Glossop.

I read the paragraph again. A peculiar feeling it gave me. I don’t know if you have ever experienced the sensation of seeing the announcement of the engagement of a pal of yours to a girl whom you were only saved from marrying yourself by the skin of your teeth. It induces a sort of—well, it’s difficult to describe it exactly; but I should imagine a fellow would feel much the same if he happened to be strolling through the jungle with a boyhood chum and met a tigress or a jaguar, or what not, and managed to shin up a tree, and looked down and saw the friend of his youth vanishing into the undergrowth in the animal’s slavering jaws. A sort of profound, prayerful relief, if you know what I mean, blended at the same time with a pang of pity. What I’m driving at is that, thankful as I was that I hadn’t had to marry Honoria myself, I was sorry to see a real good chap like old Biffy copping it. I sucked down a spot of tea and began to brood over the business.

Of course, there are probably fellows in the world—tough, hardy blokes with strong chins and glittering eyes—who could get engaged to this Glossop menace and like it; but I knew perfectly well that Biffy was not one of them. Honoria, you see, is one of those robust, dynamic girls with the muscles of a welter-weight and a laugh like a squadron of cavalry charging over a tin bridge. A beastly thing to have to face over the breakfast table. Brainy, moreover. The sort of girl who reduces you to pulp with sixteen sets of tennis and a few rounds of golf and then comes down to dinner as fresh as a daisy, expecting you to take an intelligent interest in Freud. If I had been engaged to her another week, her old father would have had one more patient on his books; and Biffy is much the same quiet sort of peaceful, inoffensive bird as me. I was shocked, I tell you, shocked.

And, as I was saying, the thing that shocked me most was Jeeves’s frightful lack of proper emotion. The man happening to trickle in at this juncture, I gave him one more chance to show some human sympathy.

“You got the name correctly, didn’t you, Jeeves?” I said. “Mr. Biffen is going to marry Honoria Glossop, the daughter of the old boy with the egg-like head and the eyebrows.”

“Yes, sir. Which suit would you wish me to lay out this morning?”

And this, mark you, from the man who, when I was engaged to the Glossop, strained every fibre in his brain to extricate me. It beat me. I couldn’t understand it.

“The blue with the red twill,” I said, coldly. My manner was marked, and I meant him to see that he had disappointed me sorely.

ABOUT a week later I went back to London, and scarcely had I got settled in the old flat when Biffy blew in. One glance was enough to tell me that the poisoned wound had begun to fester. The man did not look bright. No, there was no getting away from it, not bright. He had that kind of stunned, glassy expression which I used to see on my own face in the shaving-mirror during my brief engagement to the Glossop pestilence. However, if you don’t want to be one of the What Is Wrong With This Picture brigade, you must observe the conventions, so I shook his hand as warmly as I could.

“Well, well, old man,” I said. “Congratulations.”

“Thanks,” said Biffy, wanly, and there was rather a weighty silence.

“Thanks,” said Biffy, wanly, and there was rather a weighty silence.

“Bertie,” said Biffy, after the silence had lasted about three minutes.

“Hullo?”

“Is it really true . . . ?”

“What?”

“Oh, nothing,” said Biffy, and conversation languished again. After about a minute and a half he came to the surface once more.

“Bertie.”

“Still here, old thing. What is it?”

“I say, Bertie, is it really true that you were once engaged to Honoria?”

“It is.”

Biffy coughed.

“How did you get out—I mean, what was the nature of the tragedy that prevented the marriage?”

“Jeeves worked it. He thought out the entire scheme.”

“I think, before I go,” said Biffy, thoughtfully, “I’ll just step into the kitchen and have a word with Jeeves.”

I felt that the situation called for complete candour.

“Biffy, old egg,” I said, “as man to man, do you want to oil out of this thing?”

“Bertie, old cork,” said Biffy, earnestly, “as one friend to another, I do.”

“Then why the dickens did you ever get into it?”

“I don’t know. Why did you?”

“I—well, it sort of happened.”

“And it sort of happened with me. You know how it is when your heart’s broken. A kind of lethargy comes over you. You get absent-minded and cease to exercise proper precautions, and the first thing you know you’re for it. I don’t know how it happened, old man, but there it is. And what I want you to tell me is, what’s the procedure?”

“You mean, how does a fellow edge out?”

“Exactly. I don’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings, Bertie, but I can’t go through with this thing. The shot is not on the board. For about a day and a half I thought it might be all right, but now—— You remember that laugh of hers?”

“I do.”

“Well, there’s that, and then all this business of never letting a fellow alone—improving his mind and so forth——”

“I know. I know.”

“Very well, then. What do you recommend? What did you mean when you said that Jeeves worked a scheme?”

“Well, you see, old Sir Roderick, who’s a loony-doctor and nothing but a loony-doctor, however much you may call him a nerve specialist, discovered that there was a modicum of insanity in my family. Nothing serious. Just one of my uncles. Used to keep rabbits in his bedroom. And the old boy came to lunch here to give me the once-over, and Jeeves arranged matters so that he went away firmly convinced that I was off my onion.”

“I see,” said Biffy, thoughtfully. “The trouble is there isn’t any insanity in my family.”

“None?”

It seemed to me almost incredible that a fellow could be such a perfect chump as dear old Biffy without a bit of assistance.

“Not a loony on the list,” he said, gloomily. “It’s just like my luck. The old boy’s coming to lunch with me to-morrow, no doubt to test me as he did you. And I never felt saner in my life.”

I thought for a moment. The idea of meeting Sir Roderick again gave me a cold shivery feeling; but when there is a chance of helping a pal we Woosters have no thought of self.

“Look here, Biffy,” I said, “I’ll tell you what. I’ll roll up for that lunch. It may easily happen that when he finds you are a pal of mine he will forbid the banns right away and no more questions asked.”

“Something in that,” said Biffy, brightening. “Awfully sporting of you, Bertie.”

“Oh, not at all,” I said. “And meanwhile I’ll consult Jeeves. Put the whole thing up to him and ask his advice. He’s never failed me yet. All brain, that chap. His head sticks out at the back and he feeds entirely on fish.”

Biffy pushed off, a good deal braced, and I went into the kitchen.

“Jeeves,” I said, “I want your help once more. I’ve just been having a painful interview with Mr. Biffen.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“It’s like this,” I said, and told him the whole thing.

It was rummy, but I could feel him freezing from the start. As a rule, when I call Jeeves into conference on one of these little problems, he’s all sympathy and bright ideas; but not to-day.

“I fear, sir,” he said, when I had finished, “it is hardly my place to intervene in a private matter affecting——”

“Oh, come!”

“No, sir. It would be taking a liberty.”

“Jeeves,” I said, tackling the blighter squarely, “what have you got against old Biffy?”

“I, sir?”

“Yes, you.”

“I assure you, sir!”

“Oh, well, if you don’t want to chip in and save a fellow-creature, I suppose I can’t make you. But let me tell you this. I am now going back to the sitting-room, and I am going to put in some very tense thinking. You’ll look pretty silly when I come and tell you that I’ve got Mr. Biffen out of the soup without your assistance. Extremely silly you’ll look.”

“Yes, sir. Shall I bring you a whisky-and-soda, sir?”

“No. Coffee! Strong and black. And if anybody wants to see me, tell ’em that I’m busy and can’t be disturbed.”

An hour later I rang the bell.

“Jeeves,” I said with hauteur.

“Yes, sir?”

“Kindly ring Mr. Biffen up on the ’phone and say that Mr. Wooster presents his compliments and that he has got it.”

I WAS feeling more than a little pleased with myself next morning as I strolled round to Biffy’s. As a rule the bright ideas you get overnight have a trick of not seeming quite so frightfully fruity when you examine them by the light of day; but this one looked as good at breakfast as it had done before dinner. I examined it narrowly from every angle, and I didn’t see how it could fail.

A few days before, my Aunt Emily’s son Harold had celebrated his sixth birthday; and, being up against the necessity of weighing in with a present of some kind, I had happened to see in a shop in the Strand a rather sprightly little gadget, well calculated in my opinion to amuse the child and endear him to one and all. It was a bunch of flowers in a sort of holder ending in an ingenious bulb attachment which, when pressed, shot about a pint and a half of pure spring water into the face of anyone who was ass enough to sniff at it. It seemed to me just the thing to please the growing mind of a kid of six, and I had rolled round with it.

But when I got to the house I found Harold sitting in the midst of a mass of gifts so luxurious and costly that I simply hadn’t the crust to contribute a thing that had set me back a mere elevenpence-ha’penny; so with rare presence of mind—for we Woosters can think quick on occasion—I wrenched my Uncle James’s card off a toy aeroplane, substituted my own, and trousered the squirt, which I took away with me. It had been lying around in my flat ever since, and it seemed to me that the time had come to send it into action.

“Well?” said Biffy, anxiously, as I curveted into his sitting-room.

The poor old bird was looking pretty green about the gills. I recognized the symptoms. I had felt much the same myself when waiting for Sir Roderick to turn up and lunch with me. How the deuce people who have anything wrong with their nerves can bring themselves to chat with that man, I can’t imagine; and yet he has the largest practice in London. Scarcely a day passes without his having to sit on somebody’s head and ring for the attendant to bring the strait-waistcoat: and his outlook on life has become so jaundiced through constant association with coves who are picking straws out of their hair that I was convinced that Biffy had merely got to press the bulb and nature would do the rest.

So I patted him on the shoulder and said: “It’s all right, old man!”

“What does Jeeves suggest?” asked Biffy, eagerly.

“Jeeves doesn’t suggest anything.”

“But you said it was all right.”

“Jeeves isn’t the only thinker in the Wooster home, my lad. I have taken over your little problem, and I can tell you at once that I have the situation well in hand.”

“You?” said Biffy.

His tone was far from flattering. It suggested a lack of faith in my abilities, and my view was that an ounce of demonstration would be worth a ton of explanation. I shoved the bouquet at him.

“Are you fond of flowers, Biffy?” I said.

“Eh?”

“Smell these.”

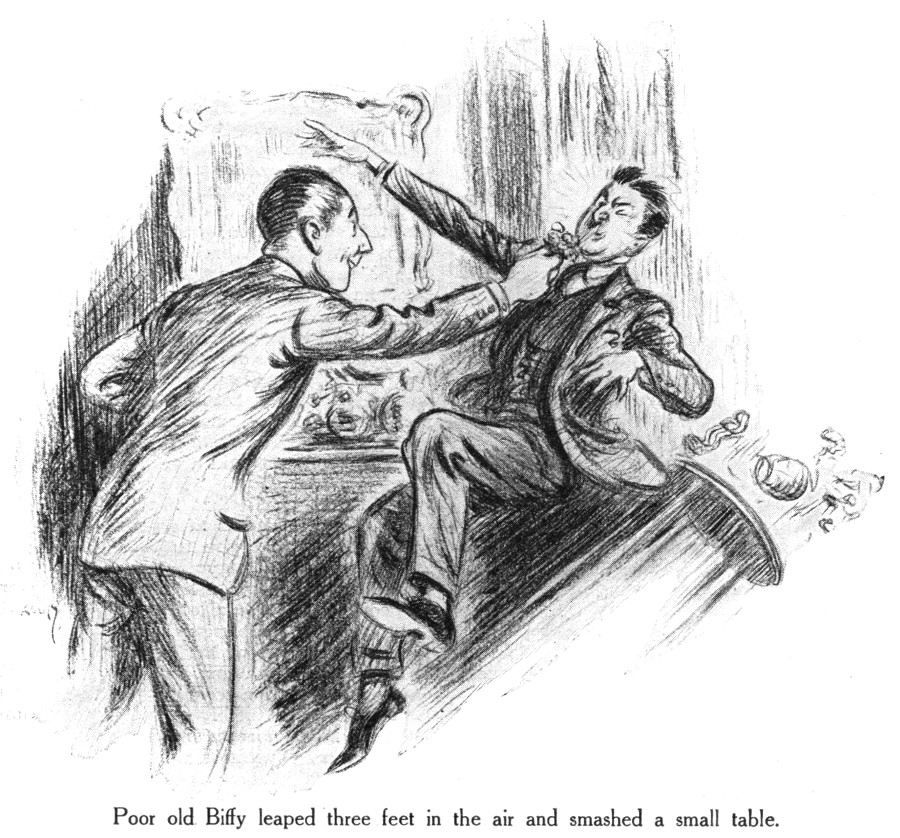

Biffy extended the old beak in a careworn sort of way, and I pressed the bulb as per printed instructions on the label.

I do like getting my money’s-worth. Elevenpence-ha’penny the thing had cost me, and it would have been cheap at double. The advertisement on the outside of the box had said that its effects were “indescribably ludicrous,” and I can testify that it was no over-statement. Poor old Biffy leaped three feet in the air and smashed a small table.

“There!” I said.

The old egg was a trifle incoherent at first, but he found words fairly soon and began to express himself with a good deal of warmth.

“Calm yourself, laddie,” I said, as he paused for breath. “It was no mere jest to pass an idle hour. It was a demonstration. Take this, Biffy, with an old friend’s blessing, refill the bulb, shove it into Sir Roderick’s face, press firmly, and leave the rest to him. I’ll guarantee that in something under three seconds the idea will have dawned on him that you are not required in his family.”

Biffy stared at me.

“Are you suggesting that I squirt Sir Roderick?”

“Absolutely. Squirt him good. Squirt as you have never squirted before.”

“But——”

He was still yammering at me in a feverish sort of way when there was a ring at the front-door bell.

“Good Lord!” cried Biffy, quivering like a jelly. “There he is. Talk to him while I go and change my shirt.”

I had just time to refill the bulb and shove it beside Biffy’s plate, when the door opened and Sir Roderick came in. I was picking up the fallen table at the moment, and he started talking brightly to my back.

“Good afternoon. I trust I am not—— Mr. Wooster!”

I’m bound to say I was not feeling entirely at my ease. There is something about the man that is calculated to strike terror into the stoutest heart. If ever there was a bloke at the very mention of whose name it would be excusable for people to tremble like aspens, that bloke is Sir Roderick Glossop. He has an enormous bald head, all the hair which ought to be on it seeming to have run into his eyebrows, and his eyes go through you like a couple of Death Rays.

“How are you, how are you, how are you?” I said, overcoming a slight desire to leap backwards out of the window. “Long time since we met, what?”

“Nevertheless, I remember you most distinctly, Mr. Wooster.”

“That’s fine,” I said. “Old Biffy asked me to come and join you in mangling a bit of lunch.”

He waggled the eyebrows at me.

“Are you a friend of Charles Biffen?”

“Oh, rather. Been friends for years and years.”

He drew in his breath sharply, and I could see that Biffy’s stock had dropped several points. His eye fell on the floor, which was strewn with things that had tumbled off the upset table.

“Have you had an accident?” he said.

“Nothing serious,” I explained. “Old Biffy had some sort of fit or seizure just now and knocked over the table.”

“A fit!”

“Or seizure.”

“Is he subject to fits?”

I was about to answer, when Biffy hurried in. He had forgotten to brush his hair, which gave him a wild look, and I saw the old boy direct a keen glance at him. It seemed to me that what you might call the preliminary spade-work had been most satisfactorily attended to and that the success of the good old bulb could be in no doubt whatever.

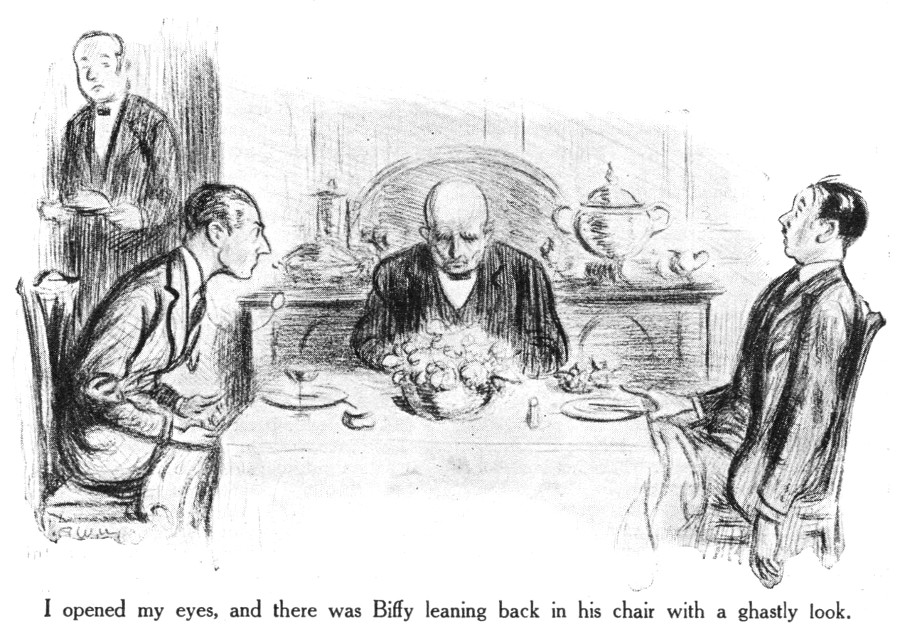

Biffy’s man came in with the nose-bags and we sat down to lunch.

IT looked at first as though the meal was going to be one of those complete frosts which occur from time to time in the career of a constant luncher-out. Biffy, a very C-3 host, contributed nothing to the feast of reason and flow of soul beyond an occasional hiccup, and every time I started to pull a nifty, Sir Roderick swung round on me with such a piercing stare that it stopped me in my tracks. Fortunately, however, the second course consisted of a chicken fricassee of such outstanding excellence that the old boy, after wolfing a plateful, handed up his dinner-pail for a second instalment and became almost genial.

“I am here this afternoon, Charles,” he said, with what practically amounted to bonhomie, “on what I might describe as a mission. Yes, a mission. This is most excellent chicken.”

“Glad you like it,” mumbled old Biffy.

“Singularly toothsome,” said Sir Roderick, pronging another half ounce. “Yes, as I was saying, a mission. You young fellows nowadays are, I know, content to live in the centre of the most wonderful metropolis the world has seen, blind and indifferent to its many marvels. I should be prepared—were I a betting man, which I am not—to wager a considerable sum that you have never in your life visited even so historic a spot as Westminster Abbey. Am I right?”

Biffy gurgled something about always having meant to.

“Nor the Tower of London?”

No, nor the Tower of London.

“And there exists at this very moment, not twenty minutes by cab from Hyde Park Corner, the most supremely absorbing and educational collection of objects, both animate and inanimate, gathered from the four corners of the Empire, that has ever been assembled in England’s history. I allude to the British Empire Exhibition now situated at Wembley.”

“Leslie Henson told me one about Wembley yesterday,” I said, to help on the cheery flow of conversation. “Stop me if you’ve heard it before. Chap goes up to deaf chap outside the exhibition and says, ‘Is this Wembley?’ ‘Hey?’ says deaf chap. ‘Is this Wembley?’ says chap. ‘Hey?’ says deaf chap. ‘Is this Wembley?’ says chap. ‘No, Thursday,’ says deaf chap. Ha, ha, I mean, what?”

The merry laughter froze on my lips. Sir Roderick sort of just waggled an eyebrow in my direction and I saw that it was back to the basket for Bertram. I never met a man who had such a knack of making a fellow feel like a waste-product.

“Have you yet paid a visit to Wembley, Charles?” he asked. “No? Precisely as I suspected. Well, that is the mission on which I am here this afternoon. Honoria wishes me to take you to Wembley. She says it will broaden your mind, in which view I am at one with her. We will start immediately after luncheon.”

Biffy cast an imploring look at me.

“You’ll come too, Bertie?”

There was such agony in his eyes that I only hesitated for a second. A pal is a pal. Besides, I felt that, if only the bulb fulfilled the high expectations I had formed of it, the merry expedition would be cancelled in no uncertain manner.

“Oh, rather,” I said.

“We must not trespass on Mr. Wooster’s good nature,” said Sir Roderick, looking pretty puff-faced.

“Oh, that’s all right,” I said. “I’ve been meaning to go to the good old exhibish for a long time. I’ll slip home and change my clothes and pick you up here in my car.”

There was a silence. Biffy seemed too relieved at the thought of not having to spend the afternoon alone with Sir Roderick to be capable of speech, and Sir Roderick was registering silent disapproval. And then he caught sight of the bouquet by Biffy’s plate.

“Ah, flowers,” he said. “Sweet peas, if I am not in error. A charming plant, pleasing alike to the eye and the nose.”

I caught Biffy’s eye across the table. It was bulging, and a strange light shone in it.

“Are you fond of flowers, Sir Roderick?” he croaked.

“Extremely.”

“Smell these.”

Sir Roderick dipped his head and sniffed. Biffy’s fingers closed slowly over the bulb. I shut my eyes and clutched the table.

“Very pleasant,” I heard Sir Roderick say. “Very pleasant indeed.”

I opened my eyes, and there was Biffy leaning back in his chair with a ghastly look, and the bouquet on the cloth beside him. I realized what had happened. In that supreme crisis of his life, with his whole happiness depending on a mere pressure of the fingers, Biffy, the poor spineless fish, had lost his nerve. My closely-reasoned scheme had gone phut.

JEEVES was fooling about with the geraniums in the sitting-room window-box when I got home.

“They make a very nice display, sir,” he said, cocking a paternal eye at the things.

“Don’t talk to me about flowers,” I said. “Jeeves, I know now how a general feels when he plans out some great scientific movement and his troops let him down at the eleventh hour.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Yes,” I said, and told him what had happened.

He listened thoughtfully.

“A somewhat vacillating and changeable young gentleman, Mr. Biffen,” was his comment when I had finished. “Would you be requiring me for the remainder of the afternoon, sir?”

“No. I’m going to Wembley. I just came back to change and get the car. Produce some fairly durable garments which can stand getting squashed by the many-headed, Jeeves, and then ’phone to the garage.”

“Very good, sir. The grey cheviot lounge will, I fancy, be suitable. Would it be too much if I asked you to give me a seat in the car, sir? I had thought of going to Wembley myself this afternoon.”

“Eh? Oh, all right.”

“Thank you very much, sir.”

I got dressed, and we drove round to Biffy’s flat. Biffy and Sir Roderick got in at the back and Jeeves climbed into the front seat next to me. Biffy looked so ill-attuned to an afternoon’s pleasure that my heart bled for the blighter and I made one last attempt to appeal to Jeeves’s better feelings.

“I must say, Jeeves,” I said, “I’m dashed disappointed in you.”

“I am sorry to hear that, sir.”

“Well, I am. Dashed disappointed. I do think you might rally round. Did you see Mr. Biffen’s face?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, then.”

“If you will pardon my saying so, sir, Mr. Biffen has surely only himself to thank if he has entered upon matrimonial obligations which do not please him.”

“You’re talking absolute rot, Jeeves. You know as well as I do that Honoria Glossop is an Act of God. You might just as well blame a fellow for getting run over by a truck.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Absolutely yes. Besides, the poor ass wasn’t in a condition to resist. He told me all about it. He had lost the only girl he had ever loved, and you know what a man’s like when that happens to him.”

“How was that, sir?”

“Apparently he fell in love with some girl on the boat going over to New York, and they parted at the Customs sheds, arranging to meet next day at her hotel. Well, you know what Biffy’s like. He forgets his own name half the time. He never made a note of the address, and it passed clean out of his mind. He went about in a sort of trance, and suddenly woke up to find that he was engaged to Honoria Glossop.”

“I did not know of this, sir.”

“I don’t suppose anybody knows of it except me. He told me when I was in Paris.”

“I should have supposed it would have been feasible to make inquiries, sir.”

“That’s what I said. But he had forgotten her name.”

“That sounds remarkable, sir.”

“I said that, too. But it’s a fact. All he remembered was that her Christian name was Mabel. Well, you can’t go scouring New York for a girl named Mabel, what?”

“I appreciate the difficulty, sir.”

“Well, there it is, then.”

“I see, sir.”

We had got into a mob of vehicles outside the Exhibition by this time, and, some tricky driving being indicated, I had to suspend the conversation. We parked ourselves eventually and went in. Jeeves drifted away, and Sir Roderick took charge of the expedition. He headed for the Palace of Industry, with Biffy and myself trailing behind.

Well, you know, I have never been much of a lad for exhibitions. The citizenry in the mass always rather puts me off, and after I have been shuffling along with the multitude for a quarter of an hour or so I feel as if I were walking on hot bricks. About this particular binge, too, there seemed to me a lack of what you might call human interest. I mean to say, millions of people, no doubt, are so constituted that they scream with joy and excitement at the spectacle of a stuffed porcupine-fish or a glass jar of seeds from Western Australia—but not Bertram. No; if you will take the word of one who would not deceive you, not Bertram. By the time we had tottered out of the Gold Coast village and were working towards the Palace of Machinery, everything pointed to my shortly executing a quiet sneak in the direction of that rather jolly Planters’ Bar in the West Indian section. Sir Roderick had whizzed us past this at a high rate of speed, it touching no chord in him; but I had been able to observe that there was a sprightly sportsman behind the counter mixing things out of bottles and stirring them up with a stick in long glasses that seemed to have ice in them, and the urge came upon me to see more of this man. I was about to drop away from the main body and become a straggler, when something pawed at my coat-sleeve. It was Biffy, and he had the air of one who has had about sufficient.

There are certain moments in life when words are not needed. I looked at Biffy, Biffy looked at me. A perfect understanding linked our two souls.

“?”

“!”

Three minutes later we had joined the Planters.

I HAVE never been in the West Indies, but I am in a position to state that in certain of the fundamentals of life they are streets ahead of our European civilization. The man behind the counter, as kindly a bloke as I ever wish to meet, seemed to guess our requirements the moment we hove in view. Scarcely had our elbows touched the wood before he was leaping to and fro, bringing down a new bottle with each leap. A planter, apparently, does not consider he has had a drink unless it contains at least seven ingredients, and I’m not saying, mind you, that he isn’t right. The man behind the bar told us the things were called Green Swizzles; and, if ever I marry and have a son, Green Swizzle Wooster is the name that will go down on the register, in memory of the day his father’s life was saved at Wembley.

After the third, Biffy breathed a contented sigh.

“Where do you think Sir Roderick is?” he said.

“Biffy, old thing,” I replied, frankly, “I’m not worrying.”

“Bertie, old bird,” said Biffy, “nor am I.”

He sighed again, and broke a long silence by asking the man for a straw.

“Bertie,” he said, “I’ve just remembered something rather rummy. You know Jeeves?”

I said I knew Jeeves.

“Well, a rather rummy incident occurred as we were going into this place. Old Jeeves sidled up to me and said something rather rummy. You’ll never guess what it was.”

“No. I don’t believe I ever shall.”

“Jeeves said,” proceeded Biffy, earnestly, “and I am quoting his very words—Jeeves said, ‘Mr. Biffen’—addressing me, you understand——”

“I understand.”

“ ‘Mr. Biffen,’ he said, ‘I strongly advise you to visit the——’ ”

“The what?” I asked, as he paused.

“Bertie, old man,” said Biffy, deeply concerned, “I’ve absolutely forgotten!”

I stared at the man.

“What I can’t understand,” I said, “is how you manage to run that Herefordshire place of yours for a day. How on earth do you remember to milk the cows and give the pigs their dinner?”

“Oh, that’s all right! There are divers blokes about the places—hirelings and menials, you know—who look after all that.”

“Ah!” I said. “Well, that being so, let us have one more Green Swizzle, and then hey for the Amusement Park.”

WHEN I indulged in those few rather bitter words about exhibitions, it must be distinctly understood that I was not alluding to what you might call the more earthy portion of these curious places. I yield to no man in my approval of those institutions where on payment of a shilling you are permitted to slide down a slippery run-way sitting on a mat. I love the Jiggle-Joggle, and I am prepared to take on all and sundry at Skee Ball for money, stamps, or Brazil nuts.

But, joyous reveller as I am on these occasions, I was simply not in it with old Biffy. Whether it was the Green Swizzles or merely the relief of being parted from Sir Roderick, I don’t know, but Biffy flung himself into the pastimes of the proletariat with a zest that was almost frightening. I could hardly drag him away from the Whip, and as for the Switchback, he looked like spending the rest of his life on it. I managed to remove him at last, and he was wandering through the crowd at my side with gleaming eyes, hesitating between having his fortune told and taking a whirl at the Wheel of Joy, when he suddenly grabbed my arm and uttered a sharp animal cry.

“Bertie!”

“Now what?”

He was pointing at a large sign over a building.

“Look! Palace of Beauty!”

I tried to choke him off. I was getting a bit weary by this time. Not so young as I was.

“You don’t want to go in there,” I said. “A fellow at the club was telling me about that. It’s only a lot of girls. You don’t want to see a lot of girls.”

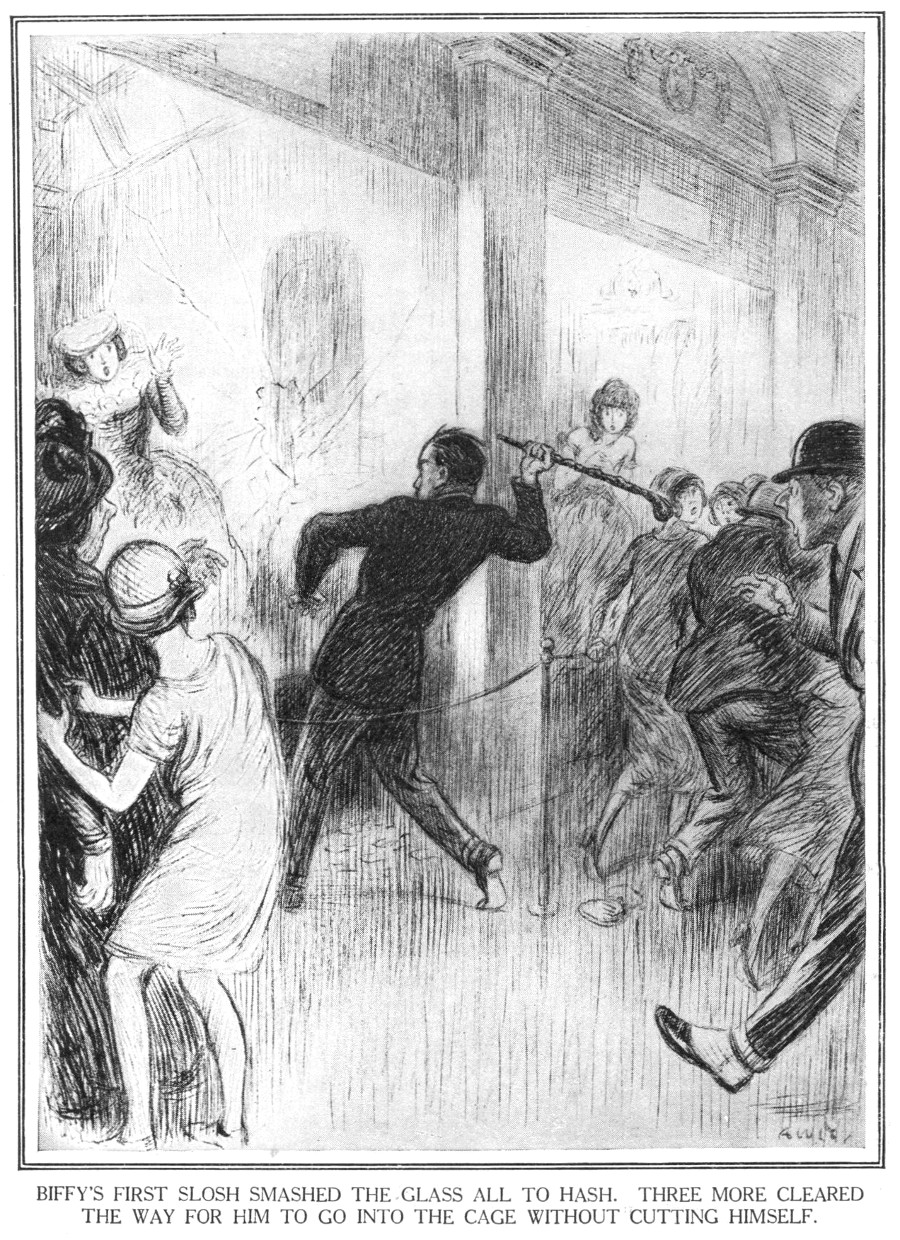

“I do want to see a lot of girls,” said Biffy, firmly. “Dozens of girls, and the more unlike Honoria they are, the better. Besides, I’ve suddenly remembered that that’s the place Jeeves told me to be sure and visit. It all comes back to me. ‘Mr. Biffen,’ he said, ‘I strongly advise you to visit the Palace of Beauty.’ Now, what the man was driving at or what his motive was, I don’t know; but I ask you, Bertie, is it wise, is it safe, is it judicious ever to ignore Jeeves’s lightest word? We enter by the door on the left.”

I don’t know if you know this Palace of Beauty place? It’s a sort of aquarium full of the delicately-nurtured instead of fishes. You go in, and there is a kind of cage with a female goggling out at you through a sheet of plate glass. She’s dressed in some weird kind of costume, and over the cage is written “Helen of Troy.” You pass on to the next, and there’s another one doing jiu-jitsu with a snake. Sub-title, Cleopatra. You get the idea—Famous Women Through the Ages and all that. I can’t say it fascinated me to any great extent. I maintain that lovely woman loses a lot of her charm if you have to stare at her in a tank. Moreover, it gave me a rummy sort of feeling of having wandered into the wrong bedroom at a country house, and I was flying past at a fair rate of speed, anxious to get it over, when Biffy suddenly went off his rocker.

At least, it looked like that. He let out a piercing yell, grabbed my arm with a sudden clutch that felt like the bite of a crocodile, and stood there gibbering.

“Wuk!” ejaculated Biffy, or words to that general import.

A large and interested crowd had gathered round. I think they thought the girls were going to be fed or something. But Biffy paid no attention to them. He was pointing in a loony manner at one of the cages. I forget which it was, but the female inside wore a ruff, so it may have been Queen Elizabeth or Boadicea or someone of that period. She was rather a nice-looking girl, and she was staring at Biffy in much the same pop-eyed way as he was staring at her.

“Mabel!” yelled Biffy, going off in my ear like a bomb.

I can’t say I was feeling my chirpiest. Drama is all very well, but I hate getting mixed up in it in a public spot; and I had not realized before how dashed public this spot was. The crowd seemed to have doubled itself in the last five seconds, and, while most of them had their eye on Biffy, quite a goodish few were looking at me as if they thought I was an important principal in the scene and might be expected at any moment to give of my best in the way of wholesome entertainment for the masses.

Biffy was jumping about like a lamb in the springtime—and, what is more, a feeble-minded lamb.

“Bertie! It’s her! It’s she!” He looked about him wildly. “Where the deuce is the stage-door?” he cried. “Where’s the manager? I want to see the house-manager immediately.”

And then he suddenly bounded forward and began hammering on the glass with his stick.

“I say, old lad!” I began, but he shook me off.

These fellows who live in the country are apt to go in for fairly sizeable clubs instead of the light canes which your well-dressed man about town considers suitable for metropolitan use; and down in Herefordshire, apparently, something in the nature of a knobkerrie is de rigueur. Biffy’s first slosh smashed the glass all to hash. Three more cleared the way for him to go into the cage without cutting himself. And, before the crowd had time to realize what a wonderful bob’s-worth it was getting in exchange for its entrance-fee, he was inside, engaging the girl in earnest conversation. And at the same moment two large policemen rolled up.

You can’t make policemen take the romantic view. Not a tear did these two blighters stop to brush away. They were inside the cage and out of it and marching Biffy through the crowd before you had time to blink. I hurried after them, to do what I could in the way of soothing Biffy’s last moments, and the poor old lad turned a glowing face in my direction.

“Chiswick, 60873,” he bellowed in a voice charged with emotion. “Write it down, Bertie, or I shall forget it. Chiswick, 60873. Her telephone number.”

And then he disappeared, accompanied by about eleven thousand sightseers, and a voice spoke at my elbow.

“Mr. Wooster! What—what—what is the meaning of this?”

Sir Roderick, with bigger eyebrows than ever, was standing at my side.

“It’s all right,” I said. “Poor old Biffy’s only gone off his crumpet.”

He tottered.

“What?”

“Had a sort of fit or seizure, you know.”

“Another!” Sir Roderick drew a deep breath. “And this is the man I was about to allow my daughter to marry!” I heard him mutter.

I tapped him in a kindly spirit on the shoulder. It took some doing, mark you, but I did it.

“If I were you,” I said, “I should call that off. Scratch the fixture. Wash it out absolutely, is my advice.”

He gave me a nasty look.

“I do not require your advice, Mr. Wooster! I had already arrived independently at the decision of which you speak. Mr. Wooster, you are a friend of this man—a fact which should in itself have been sufficient warning to me. You will—unlike myself—be seeing him again. Kindly inform him, when you do see him, that he may consider his engagement at an end.”

“Right-ho,” I said, and hurried off after the crowd. It seemed to me that a little bailing-out might be in order.

IT was about an hour later that I shoved my way out to where I had parked the car. Jeeves was sitting in the front seat, brooding over the cosmos. He rose courteously as I approached.

“You are leaving, sir?”

“I am.”

“And Sir Roderick, sir?”

“Not coming. I am revealing no secrets, Jeeves, when I inform you that he and I have parted brass-rags. Not on speaking terms now.”

“Indeed, sir? And Mr. Biffen? Will you wait for him?”

“No. He’s in prison.”

“Really, sir?”

“Yes. Laden down with chains in the deepest dungeon beneath the castle moat. I tried to bail him out, but they decided on second thoughts to coop him up for the night.”

“What was his offence, sir?”

“You remember that girl of his I was telling you about? He found her in a tank at the Palace of Beauty and went after her by the quickest route, which was viâ a plate-glass window. He was then scooped up and borne off in irons by the constabulary.” I gazed sideways at him. It is difficult to bring off a penetrating glance out of the corner of your eye, but I managed it. “Jeeves,” I said, “there is more in this than the casual observer would suppose. You told Mr. Biffen to go to the Palace of Beauty. Did you know the girl would be there?”

“Yes, sir.”

This was most remarkable and rummy to a degree.

“Dash it, do you know everything?”

“Oh, no, sir,” said Jeeves, with an indulgent smile. Humouring the young master.

“Well, how did you know that?”

“I happen to be acquainted with the future Mrs. Biffen, sir.”

“I see. Then you knew all about that business in New York?”

“Yes, sir. And it was for that reason that I was not altogether favourably disposed towards Mr. Biffen when you were first kind enough to suggest that I might be able to offer some slight assistance. I mistakenly supposed that he had been trifling with the girl’s affections, sir. But when you told me the true facts of the case I appreciated the injustice I had done to Mr. Biffen and endeavoured to make amends.”

“Well, he certainly owes you a lot. He’s crazy about her.”

“That is very gratifying, sir.”

“And she ought to be pretty grateful to you, too. Old Biffy’s got fifteen thousand a year, not to mention more cows, pigs, hens, and ducks than he knows what to do with. A dashed useful bird to have in any family.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Tell me, Jeeves,” I said, “how did you happen to know the girl in the first place?”

Jeeves looked dreamily out into the traffic.

“She is my niece, sir. If I might make the suggestion, sir, I should not jerk the steering-wheel with quite such suddenness. We very nearly collided with that omnibus.”

(Another story by P. G. Wodehouse next month.)

Annotations for this story are elsewhere on this site.

Compare the American magazine version from the Saturday Evening Post, September 27, 1924.

Only in this Strand version is the Wembley joke credited to real-life comedian Leslie Henson (1891–1957); other versions credit only “a fellow” (book) or “a fellow at the club” (SEP).

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums