The Strand Magazine, December 1922

“AFTER all,” said the young man, “golf is only a game.”

He spoke bitterly and with the air of one who has been following a train of thought. He had come into the smoking-room of the club-house in low spirits at the dusky close of a November evening, and for some minutes had been sitting, silent and moody, staring at the log fire.

“Merely a pastime,” said the young man.

The Oldest Member, nodding in his armchair, stiffened with horror, and glanced quickly over his shoulder to make sure that none of the waiters had heard these terrible words.

“Can this be George William Pennefather speaking!” he said, reproachfully. “My boy, you are not yourself.”

The young man flushed a little beneath his tan: for he had had a good upbringing and was not bad at heart.

“Perhaps I ought not to have gone quite so far as that,” he admitted. “I was only thinking that a fellow’s got no right, just because he happens to have come on a bit in his form lately, to treat a fellow as if a fellow was a leper or something.”

The Oldest Member’s face cleared, and he breathed a relieved sigh.

“Ah! I see,” he said. “You spoke hastily and in a sudden fit of pique because something upset you out on the links to-day. Tell me all. Let me see, you were playing with Nathaniel Frisby this afternoon, were you not? I gather that he beat you.”

“Yes, he did. Giving me a third. But it isn’t being beaten that I mind. What I object to is having the blighter behave as if he were a sort of champion condescending to a mere mortal. Dash it, it seemed to bore him playing with me. Every time I sliced off the tee he looked at me as if I were a painful ordeal. Twice when I was having a bit of trouble in the bushes I caught him yawning. And after we had finished he started talking about what a good game croquet was, and he wondered more people didn’t take it up. And it’s only a month or so ago that I could play the man level!”

The Oldest Member shook his snowy head sadly.

“There is nothing to be done about it,” he said. “We can only hope that the poison will in time work its way out of the man’s system. Sudden success at golf is like the sudden acquisition of wealth. It is apt to unsettle and deteriorate the character. And, as it comes almost miraculously, so only a miracle can effect a cure. The best advice I can give you is to refrain from playing with Nathaniel Frisby till you can keep your tee-shots straight.”

“Oh, but don’t run away with the idea that I wasn’t pretty good off the tee this afternoon!” said the young man. “I should like to describe to you the shot I did on the——”

“Meanwhile,” proceeded the Oldest Member, “I will relate to you a little story which bears on what I have been saying.”

“From the very moment I addressed the ball——”

“It is the story of two loving hearts temporarily estranged owing to the sudden and unforeseen proficiency of one of the couple——”

“I waggled quickly and strongly, like Duncan. Then, swinging smoothly back, rather in the Vardon manner——”

“But as I see,” said the Oldest Member, “that you are all impatience for me to begin, I will do so without further preamble.”

TO the philosophical student of golf like myself (said the Oldest Member) perhaps the most outstanding virtue of this noble pursuit is the fact that it is a medicine for the soul. Its great service to humanity is that it teaches human beings that, whatever petty triumphs they may have achieved in other walks of life, they are after all merely human. It acts as a corrective against sinful pride. I attribute the insane arrogance of the later Roman emperors almost entirely to the fact that, never having played golf, they never knew that strange, chastening humility which is engendered by a topped chip-shot. If Cleopatra had been outed in the first round of the Ladies’ Singles, we should have heard a lot less of her proud imperiousness. And, coming down to modern times, it was undoubtedly his rotten golf that kept Wallace Chesney the nice unspoiled fellow he was. For in every other respect he had everything in the world calculated to make a man conceited and arrogant. He was the best-looking man for miles around; his health was perfect; and in addition to this he was rich; danced, rode, played bridge and polo with equal skill; and was engaged to be married to Charlotte Dix. And when you saw Charlotte Dix you realized that being engaged to her would by itself have been quite enough luck for any one man.

But Wallace, as I say, despite all his advantages, was a thoroughly nice, modest young fellow. And I attribute this to the fact that, while one of the keenest golfers in the club, he was also one of the worst players. Indeed, Charlotte Dix used to say to me in his presence that she could not understand why people paid money to go to the circus when by merely walking over the brow of a hill they could watch Wallace Chesney trying to get out of the bunker by the eleventh green. And Wallace took the gibe with perfect good humour, for there was a delightful camaraderie between them which robbed it of any sting. Often at lunch in the club-house I used to hear him and Charlotte planning the handicapping details of a proposed match between Wallace and a non-existent cripple whom Charlotte claimed to have discovered in the village—it being agreed finally that he should accept seven bisques from the cripple, but that, if the latter ever recovered the use of his arms, Wallace should get a stroke a hole.

In short, a thoroughly happy and united young couple. Two hearts, if I may coin an expression, that beat as one.

I would not have you misjudge Wallace Chesney. I may have given you the impression that his attitude towards golf was light and frivolous, but such was not the case. As I have said, he was one of the keenest members of the club. Love made him receive the joshing of his fiancée in the kindly spirit in which it was meant, but at heart he was as earnest as you could wish. He practised early and late; he bought golf books; and the mere sight of a patent club of any description acted on him like catnip on a cat. I remember remonstrating with him on the occasion of his purchasing a wooden-faced driving-mashie which weighed about two pounds, and was, taking it for all in all, as foul an instrument as ever came out of the workshop of a clubmaker who had been dropped on the head by his nurse when a baby.

“I know, I know,” he said, when I had finished indicating some of the weapon’s more obvious defects. “But the point is, I believe in it. It gives me confidence. I don’t believe you could slice with a thing like that if you tried.”

Confidence! That was what Wallace Chesney lacked, and that, as he saw it, was the prime grand secret of golf. Like an alchemist on the track of the Philosopher’s Stone, he was for ever seeking for something which would really give him confidence. I recollect that he even tried repeating to himself fifty times every morning the words, “Every day in every way I grow better and better.” This, however, proved such a black lie that he gave it up. The fact is, the man was a visionary, and it is to auto-hypnosis of some kind that I attribute the extraordinary change that came over him at the beginning of his third season.

You may have noticed in your perambulations about the City a shop bearing above its door and upon its windows the legend:—

COHEN BROS.,

Second-hand Clothiers,

a statement which is borne out by endless vistas seen through the door of every variety of what is technically known as Gents’ Wear. But the Brothers Cohen, though their main stock-in-trade is garments which have been rejected by their owners for one reason or another, do not confine their dealings to Gents’ Wear. The place is a museum of derelict goods of every description. You can get a second-hand revolver there, or a second-hand sword, or a second-hand umbrella. You can do a cheap deal in field-glasses, trunks, dog collars, canes, photograph frames, attaché cases, and bowls for goldfish. And on the bright spring morning when Wallace Chesney happened to pass by there was exhibited in the window a putter of such pre-eminently lunatic design that he stopped dead as if he had run into an invisible wall, and then, panting like an overwrought fish, charged in through the door.

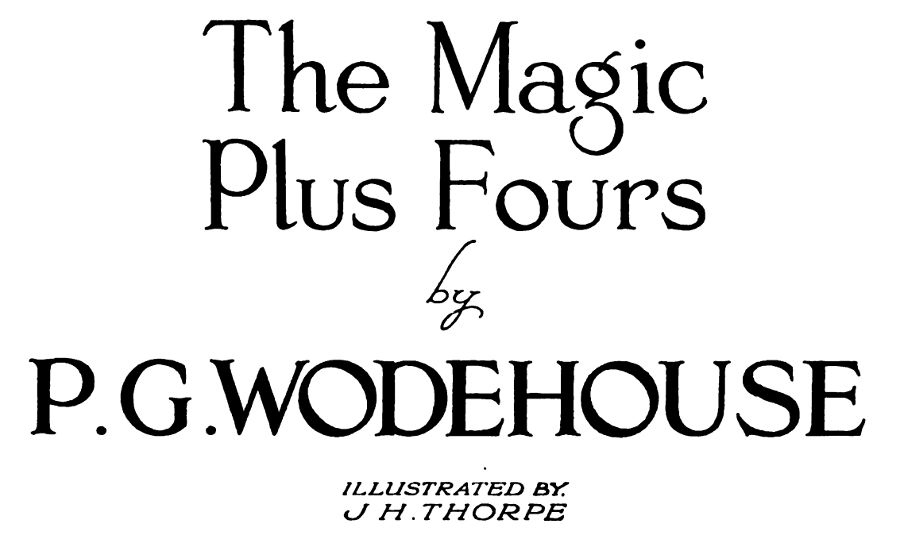

THE shop was full of the Cohen family, sombre-eyed, smileless men with purposeful expressions; and two of these, instantly descending upon Wallace Chesney like leopards, began in swift silence to thrust him into a suit of yellow tweed. Having worked the coat over his shoulders with a shoe-horn, they stood back to watch the effect.

“A beautiful fit,” announced Isidore Cohen.

“A little snug under the arms,” said his brother Irving. “But that’ll give.”

“The warmth of the body will make it give,” said Isidore.

“Or maybe you’ll lose weight in the summer,” said Irving.

Wallace, when he had struggled out of the coat and was able to breathe, said that he had come in to buy a putter. Isidore thereupon sold him the putter, a dog collar, and a set of studs, and Irving sold him a fireman’s helmet: and he was about to leave when their elder brother Lou, who had just finished fitting out another customer, who had come in to buy a cap, with two pairs of trousers and a miniature aquarium for keeping newts in, saw that business was in progress and strolled up. His fathomless eye rested on Wallace, who was toying feebly with the putter.

“You play golf?” asked Lou. “Then looka here!”

He dived into an alleyway of dead clothing, dug for a moment, and emerged with something at the sight of which Wallace Chesney, hardened golfer that he was, blenched and threw up an arm defensively.

“No, no!” he cried.

The object which Lou Cohen was waving insinuatingly before his eyes was a pair of those golfing breeches which are technically known as Plus Fours. A player of two years’ standing, Wallace Chesney was not unfamiliar with Plus Fours—all the club cracks wore them—but he had never seen Plus Fours like these. What might be termed the main motif of the fabric was a curious vivid pink, and with this to work on the architect had let his imagination run free, and had produced so much variety in the way of chessboard squares of white, yellow, violet, and green that the eye swam as it looked upon them.

“These were made to measure for Sandy McHoots, the Open Champion,” said Lou, stroking the left leg lovingly. “But he sent ’em back for some reason or other.”

“Perhaps they frightened the children,” said Wallace, recollecting having heard that Mr. McHoots was a married man.

“They’ll fit you nice,” said Lou.

“Sure they’ll fit him nice,” said Isidore, warmly.

“Why, just take a look at yourself in the glass,” said Irving, “and see if they don’t fit you nice.”

And, as one who wakes from a trance, Wallace discovered that his lower limbs were now encased in the prismatic garment. At what point in the proceedings the brethren had slipped them on him, he could not have said. But he was undeniably in.

Wallace looked in the glass. For a moment, as he eyed his reflection, sheer horror gripped him. Then suddenly, as he gazed, he became aware that his first feelings were changing. The initial shock over, he was becoming calmer. He waggled his right leg with a certain sang-froid.

There is a certain passage in the works of the poet Pope with which you may be familiar. It runs as follows:—

Vice is a monster of so frightful mien

As to be hated needs but to be seen;

Yet seen too oft, familiar with her face,

We first endure, then pity, then embrace.

Even so was it with Wallace Chesney and these Plus Fours. At first he had recoiled from them as any decent-minded man would have done. Then, after a while, almost abruptly he found himself in the grip of a new emotion. After an unsuccessful attempt to analyse this, he suddenly got it. Amazing as it may seem, it was pleasure that he felt. He caught his eye in the mirror, and it was smirking. Now that the things were actually on, by Hutchinson, they didn’t look half bad. By Braid, they didn’t. There was a sort of something about them. Take away that expanse of bare leg with its unsightly sock-suspender and substitute a woolly stocking, and you would have the lower section of a golfer. For the first time in his life, he thought, he looked like a man who could play golf.

There came to him an odd sensation of masterfulness. He was still holding the putter, and now he swung it up above his shoulder. A fine swing, all lissomeness and supple grace, quite different from any swing he had ever done before.

Wallace Chesney gasped. He knew that at last he had discovered that prime grand secret of golf for which he had searched so long. It was the costume that did it. All you had to do was wear Plus Fours. He had always hitherto played in grey flannel trousers. Naturally he had not been able to do himself justice. Golf required an easy dash, and how could you be easily dashing in concertina-shaped trousers with a patch on the knee? He saw now—what he had never seen before—that it was not because they were crack players that crack players wore Plus Fours: it was because they wore Plus Fours that they were crack players. And these Plus Fours had been the property of an Open Champion. Wallace Chesney’s bosom swelled, and he was filled, as by some strange gas, with joy—with excitement—with confidence. Yes, for the first time in his golfing life, he felt really confident.

True, the things might have been a shade less gaudy: they might perhaps have hit the eye with a slightly less violent punch: but what of that? True, again, he could scarcely hope to avoid the censure of his club-mates when he appeared like this on the links: but what of that? His club-mates must set their teeth and learn to bear these Plus Fours like men. That was what Wallace Chesney thought about it. If they did not like his Plus Fours, let them go and play golf somewhere else.

“How much?” he muttered, thickly. And the Brothers Cohen clustered grimly round with note-books and pencils.

IN predicting a stormy reception for his new apparel, Wallace Chesney had not been unduly pessimistic. The moment he entered the club-house Disaffection reared its ugly head. Friends of years’ standing called loudly for the committee, and there was a small and vehement party of the left wing, headed by Raymond Gandle, who was an artist by profession, and consequently had a sensitive eye, which advocated the tearing off and public burial of the obnoxious garment. But, prepared as he had been for some such demonstration on the part of the coarser-minded, Wallace had hoped for better things when he should meet Charlotte Dix, the girl who loved him. Charlotte, he had supposed, would understand and sympathize.

Instead of which, she uttered a piercing cry and staggered to a bench, whence a moment later she delivered her ultimatum.

“Quick!” she said. “Before I have to look again.”

“What do you mean?”

“Pop straight back into the changing-room while I’ve got my eyes shut, and remove the fancy-dress.”

“What’s wrong with them?”

“Darling,” said Charlotte, “I think it’s sweet and patriotic of you to be proud of your cycling club colours or whatever they are, but you mustn’t wear them on the links. It will unsettle the caddies.”

“They are a trifle on the bright side,” admitted Wallace. “But it helps my game, wearing them. I was trying a few practice-shots just now, and I couldn’t go wrong. Slammed the ball on the meat every time. They inspire me, if you know what I mean. Come on, let’s be starting.”

Charlotte opened her eyes incredulously.

“You can’t seriously mean that you’re really going to play in—those? It’s against the rules. There must be a rule somewhere in the book against coming out looking like a sunset. Won’t you go and burn them for my sake?”

“But I tell you they give me confidence. I sort of squint down at them when I’m addressing the ball, and I feel like a pro.”

“Then the only thing to do is for me to play you for them. Come on, Wally, be a sportsman. I’ll give you a half and play you for the whole outfit—the breeches, the red jacket, the little cap, and the belt with the snake’s-head buckle. I’m sure all those things must have gone with the breeches. Is it a bargain?”

STROLLING on the club-house terrace some two hours later, Raymond Gandle encountered Charlotte and Wallace coming up from the eighteenth green.

“Just the girl I wanted to see,” said Raymond. “Miss Dix, I represent a select committee of my fellow-members, and I have come to ask you on their behalf to use the influence of a good woman to induce Wally to destroy those Plus Fours of his, which we all consider nothing short of Bolshevik propaganda and a menace to the public weal. May I rely on you?”

“You may not,” retorted Charlotte. “They are the poor boy’s mascot. You’ve no idea how they have improved his game. He has just beaten me hollow. I am going to try to learn to bear them, so you must. Really, you’ve no notion how he has come on. My cripple won’t be able to give him more than a couple of bisques if he keeps up this form.”

“It’s something about the things,” said Wallace. “They give me confidence.”

“They give me a pain in the neck,” said Raymond Gandle.

TO the thinking man nothing is more remarkable in this life than the way in which Humanity adjusts itself to conditions which at their outset might well have appeared intolerable. Some great cataclysm occurs, some storm or earthquake, shaking the community to its foundations; and after the first pardonable consternation one finds the sufferers resuming their ordinary pursuits as if nothing had happened. There have been few more striking examples of this adaptability than the behaviour of the members of our golf-club under the impact of Wallace Chesney’s Plus Fours. For the first few days it is not too much to say that they were stunned. Nervous players sent their caddies on in front of them at blind holes, so that they might be warned in time of Wallace’s presence ahead and not have him happening to them all of a sudden. And even the pro was not unaffected. Brought up in Scotland in an atmosphere of tartan kilts, he nevertheless winced, and a startled “Hoots!” was forced from his lips when Wallace Chesney suddenly appeared in the valley as he was about to drive from the fifth tee.

But in about a week conditions were back to normalcy. Within ten days the Plus Fours became a familiar feature of the landscape, and were accepted as such without comment. They were pointed out to strangers together with the waterfall, the Lovers’ Leap, and the view from the eighth green as things you ought not to miss when visiting the course; but apart from that one might almost say they were ignored. And meanwhile Wallace Chesney continued day by day to make the most extraordinary progress in his play.

As I said before, and I think you will agree with me when I have told you what happened subsequently, it was probably a case of auto-hypnosis. There is no other sphere in which a belief in oneself has such immediate effects as it has in golf. And Wallace, having acquired self-confidence, went on from strength to strength. In under a week he had ploughed his way through the Unfortunate Incidents—of which class Peter Willard was the best example—and was challenging the fellows who kept three shots in five somewhere on the fairway. A month later he was holding his own with ten-handicap men. And by the middle of the summer he was so far advanced that his name occasionally cropped up in speculative talks on the subject of the July medal. One might have been excused for supposing that, as far as Wallace Chesney was concerned, all was for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

And yet——

THE first inkling I received that anything was wrong came through a chance meeting with Raymond Gandle, who happened to pass my gate on his way back from the links just as I drove up in my taxi: for I had been away from home for many weeks on a protracted business tour. I welcomed Gandle’s advent and invited him in to smoke a pipe and put me abreast of local gossip. He came readily enough—and seemed, indeed, to have something on his mind and to be glad of the opportunity of revealing it to a sympathetic auditor.

“And how,” I asked him, when we were comfortably settled, “did your game this afternoon come out?”

“Oh, he beat me,” said Gandle, and it seemed to me that there was a note of bitterness in his voice.

“Then He, whoever he was, must have been an extremely competent performer?” I replied, courteously, for Gandle was one of the finest players in the club. “Unless, of course, you were giving him some impossible handicap.”

“No; we played level.”

“Indeed! Who was your opponent?”

“Chesney.”

“Wallace Chesney! And he beat you, playing level! This is the most amazing thing I have ever heard.”

“He’s improved out of all knowledge.”

“He must have done. Do you think he would ever beat you again?”

“No. Because he won’t have the chance.”

“You surely do not mean that you will not play him because you are afraid of being beaten?”

“It isn’t being beaten I mind——”

And if I omit to report the remainder of his speech it is not merely because it contained expressions with which I am reluctant to sully my lips, but because, omitting these expletives, what he said was almost word for word what you were saying to me just now about Nathaniel Frisby. It was, it seemed, Wallace Chesney’s manner, his arrogance, his attitude of belonging to some superior order of being that had so wounded Raymond Gandle. Wallace Chesney had, it appeared, criticized Gandle’s mashie-play in no friendly spirit; had hung up the game on the fourteenth tee in order to show him how to place his feet; and on the way back to the club-house had said that the beauty of golf was that the best player could enjoy a round even with a dud, because, though there might be no interest in the match, he could always amuse himself by playing for his medal score.

I was profoundly shaken.

“Wallace Chesney!” I exclaimed. “Was it really Wallace Chesney who behaved in the manner you describe?”

“Unless he’s got a twin brother of the same name, it was.”

“Wallace Chesney a victim to swelled head! I can hardly credit it.”

“Well, you needn’t take my word for it unless you want to. Ask anybody. It isn’t often he can get anyone to play with him now.”

“You horrify me!”

Raymond Gandle smoked awhile in brooding silence.

“You’ve heard about his engagement?” he said at length.

“I have heard nothing, nothing. What about his engagement?”

“Charlotte Dix has broken it off.”

“No!”

“Yes. Couldn’t stand him any longer.”

I got rid of Gandle as soon as I could. I made my way as quickly as possible to the house where Charlotte lived with her aunt. I was determined to sift this matter to the bottom and to do all that lay in my power to heal the breach between two young people for whom I had a great affection.

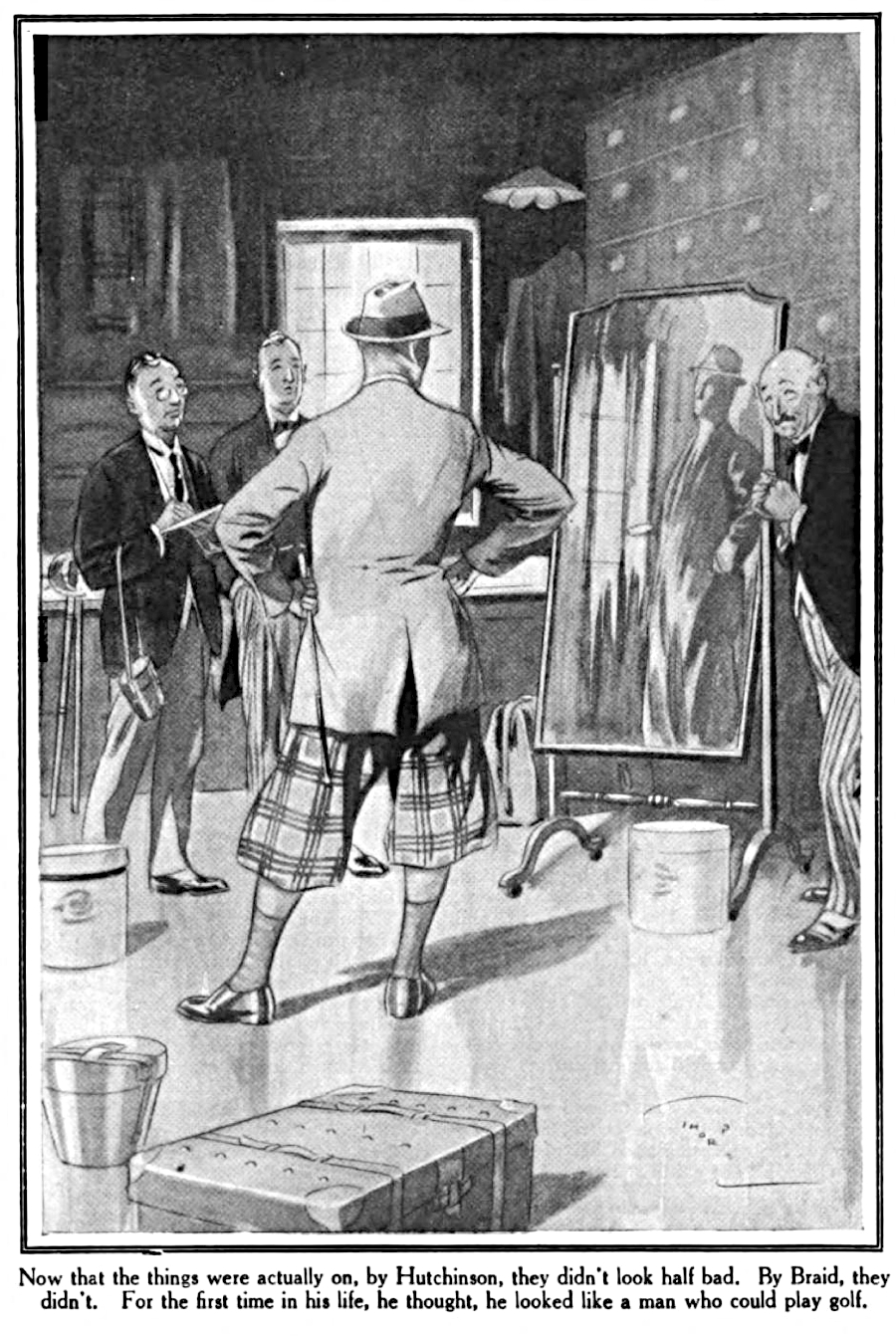

“I have just heard the news,” I said, when the aunt had retired to some secret lair, as aunts do, and Charlotte and I were alone.

“What news?” said Charlotte, dully. I thought she looked pale and ill, and she had certainly grown thinner.

“This dreadful news about your engagement to Wallace Chesney. Tell me, why did you do this thing? Is there no hope of a reconciliation?”

“Not unless Wally becomes his old self again.”

“But I had always regarded you two as ideally suited to one another.”

“Wally has changed completely in the last few weeks. Haven’t you heard?”

“Only sketchily, from Raymond Gandle.”

“I refuse,” said Charlotte, proudly, all the woman in her leaping to her eyes, “to marry a man who treats me as if I were a kronen at the present rate of exchange, merely because I slice an occasional tee-shot. The afternoon I broke off the engagement”—her voice shook, and I could see that her indifference was but a mask—“the afternoon I broke off the en-gug-gug-gagement, he t-told me I ought to use an iron off the tee instead of a dud-dud-driver.”

And the stricken girl burst into an uncontrollable fit of sobbing. And realizing that, if matters had gone as far as that, there was little I could do, I pressed her hand silently and left her.

BUT though it seemed hopeless I decided to persevere. I turned my steps towards Wallace Chesney’s bungalow, resolved to make one appeal to the man’s better feelings. He was in his sitting-room when I arrived, polishing a putter: and it seemed significant to me even in that tense moment that the putter was quite an ordinary one, such as any capable player might use. In the brave old happy days of his dudhood, the only putters you ever found in the society of Wallace Chesney were patent self-adjusting things that looked like croquet mallets that had taken the wrong turning in childhood.

“Well, Wallace, my boy,” I said.

“Hallo!” said Wallace Chesney. “So you’re back?”

We fell into conversation, and I had not been in the room two minutes before I realized that what I had been told about the change in him was nothing more than the truth. The man’s bearing and his every remark were insufferably bumptious. He spoke of his prospects in the July medal competition as if the issue were already settled. He scoffed at his rivals.

I had some little difficulty in bringing the talk round to the matter which I had come to discuss.

“My boy,” I said at length, “I have just heard the sad news.”

“What sad news?”

“I have been talking to Charlotte——”

“Oh, that!” said Wallace Chesney.

“She was telling me——”

“Perhaps it’s all for the best.”

“All for the best? What do you mean?”

“Well,” said Wallace, “one doesn’t wish, of course, to say anything ungallant, but, after all, poor Charlotte’s handicap is fourteen and wouldn’t appear to have much chance of getting any lower. I mean, there’s such a thing as a fellow throwing himself away.”

Was I revolted at these callous words? For a moment, yes. Then it struck me that, though he had uttered them with a light laugh, that laugh had had in it more than a touch of bravado. I looked at him keenly. There was a bored, discontented expression in his eyes, a line of pain about his mouth.

“My boy,” I said, gravely, “you are not happy.”

For an instant I think he would have denied the imputation. But my visit had coincided with one of those twilight moods in which a man requires above all else sympathy. He uttered a weary sigh.

“I’m fed up,” he admitted. “It’s a funny thing. When I was a dud, I used to think how perfect it must be to be scratch. I used to watch the cracks buzzing round the course and envy them. It’s all a fraud. The only time when you enjoy golf is when an occasional decent shot is enough to make you happy for the day. I’m plus two, and I’m bored to death. I’m too good. And what’s the result? Everybody’s jealous of me. Everybody’s got it in for me. Nobody loves me.”

His voice rose in a note of anguish, and at the sound his terrier, which had been sleeping on the rug, crept forward and licked his hand.

“The dog loves you,” I said, gently, for I was touched.

“Yes, but I don’t love the dog,” said Wallace Chesney.

“Now come, Wallace,” I said. “Be reasonable, my boy. It is only your unfortunate manner on the links which has made you perhaps a little unpopular at the moment. Why not pull yourself up? Why ruin your whole life with this arrogance? All that you need is a little tact, a little forbearance. Charlotte, I am sure, is just as fond of you as ever, but you have wounded her pride. Why must you be unkind about her tee-shots?”

Wallace Chesney shook his head despondently.

“I can’t help it,” he said. “It exasperates me to see anyone foozling, and I have to say so.”

“Then there is nothing to be done,” I said, sadly.

ALL the medal competitions at our club are, as you know, important events; but, as you are also aware, none of them is looked forward to so keenly or contested so hotly as the one in July. At the beginning of the year of which I am speaking, Raymond Gandle had been considered the probable winner of the fixture; but as the season progressed and Wallace Chesney’s skill developed to such a remarkable extent most of us were reluctantly inclined to put our money on the latter. Reluctantly, because Wallace’s unpopularity was now so general that the thought of his winning was distasteful to all. It grieved me to see how cold his fellow-members were towards him. He drove off from the first tee without a preliminary hand-clap; and, though the drive was of admirable quality and nearly carried the green, there was not a single cheer. I noticed Charlotte Dix among the spectators. The poor girl was looking sad and wan.

In the draw for partners Wallace had had Peter Willard allotted to him; and he muttered to me in a quite audible voice that it was as bad as handicapping him half-a-dozen strokes to make him play with such a hopeless performer. I do not think Peter heard, but it would not have made much difference to him if he had, for I doubt if anything could have had much effect for the worse on his game. Peter Willard always entered for the medal competition, because he said that competition-play was good for the nerves.

On this occasion he topped his ball badly, and Wallace lit his pipe with the exaggeratedly patient air of an irritated man. When Peter topped his second also, Wallace was moved to speech.

“For goodness’ sake,” he snapped, “what’s the good of playing at all if you insist on lifting your head? Keep it down, man, keep it down. You don’t need to watch to see where the ball is going. It isn’t likely to go as far as all that. Make up your mind to count three before you look up.”

“Thanks,” said Peter, meekly. There was no pride in Peter to be wounded. He knew the sort of player he was.

The couples were now moving off with smooth rapidity, and the course was dotted with the figures of players and their accompanying spectators. A fair proportion of these latter had decided to follow the fortunes of Raymond Gandle, but by far the larger number were sticking to Wallace, who right from the start showed that Gandle or anyone else would have to return a very fine card to beat him. He was out in forty-one, two above bogey, and with the assistance of a superb second, which landed the ball within a foot of the pin, got a three on the tenth, where a four is considered good. I mention this to show that by the time he arrived at the short lake-hole Wallace Chesney was at the top of his form. Not even the fact that he had been obliged to let the next couple through owing to Peter Willard losing his ball had been enough to upset him.

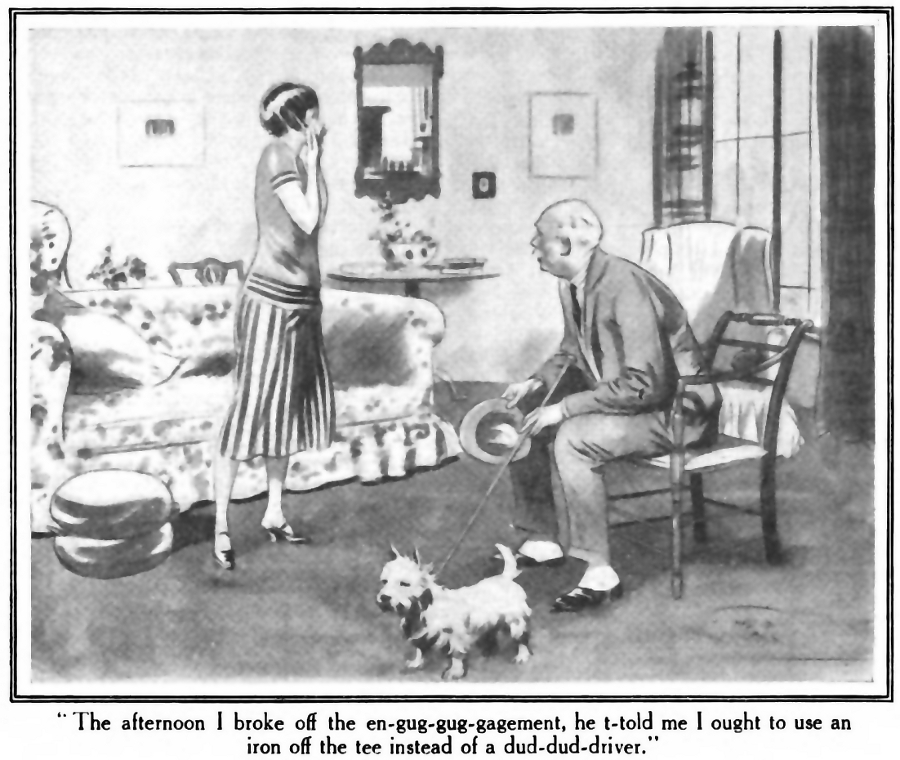

THE course has been rearranged since, but at that time the lake-hole, which is now the second, was the eleventh, and was generally looked on as the crucial hole in a medal round. Wallace no doubt realized this, but the knowledge did not seem to affect him. He lit his pipe with the utmost coolness; and, having replaced the match-box in his hip-pocket, stood smoking nonchalantly as he waited for the couple in front to get off the green.

They holed out eventually, and Wallace walked to the tee. As he did so, he was startled to receive a resounding smack.

“Sorry,” said Peter Willard, apologetically. “Hope I didn’t hurt you. A wasp.”

And he pointed to the corpse, which was lying in a used-up attitude on the ground.

“Afraid it would sting you,” said Peter.

“Oh, thanks,” said Wallace.

He spoke a little stiffly, for Peter Willard had a large, hard, flat hand, the impact of which had shaken him up considerably. Also, there had been laughter in the crowd. He was fuming as he bent to address his ball, and his annoyance became acute when, just as he reached the top of his swing, Peter Willard suddenly spoke.

“Just a second, old man,” said Peter.

Wallace spun round, outraged.

“What is it? I do wish you would wait till I’ve made my shot.”

“Just as you like,” said Peter, humbly.

“There is no greater crime that a man can commit on the links than to speak to a fellow when he’s making his stroke.”

“Of course, of course,” acquiesced Peter, crushed.

Wallace turned to his ball once more. He was vaguely conscious of a discomfort to which he could not at the moment give a name. At first he thought that he was having a spasm of lumbago, and this surprised him, for he had never in his life been subject to even a suspicion of that malady. A moment later he realized that this diagnosis had been wrong.

“Good heavens!” he cried, leaping nimbly some two feet into the air. “I’m on fire!”

“Yes,” said Peter, delighted at his ready grasp of the situation. “That’s what I wanted to mention just now.”

Wallace slapped vigorously at the seat of his Plus Fours.

“It must have been when I killed that wasp,” said Peter, beginning to see clearly into the matter. “You had a match-box in your pocket.”

Wallace was in no mood to stop and discuss first causes. He was springing up and down on his pyre, beating at the flames.

“Do you know what I should do if I were you?” said Peter Willard. “I should jump into the lake.”

One of the cardinal rules of golf is that a player shall accept no advice from anyone but his own caddie; but the warmth about his lower limbs had now become so generous that Wallace was prepared to stretch a point. He took three rapid strides and entered the water with a splash.

The lake, though muddy, is not deep, and presently Wallace was to be observed standing up to his waist some few feet from the shore.

“That ought to have put it out,” said Peter Willard. “It was a bit of luck that it happened at this hole.” He stretched out a hand to the bather. “Catch hold, old man, and I’ll pull you out.”

“No!” said Wallace Chesney.

“Why not?”

“Never mind!” said Wallace, austerely. He bent as near to Peter as he was able. “Send a caddie up to the club-house to fetch my grey flannel trousers from my locker,” he whispered, tensely.

“Oh, ah!” said Peter.

It was some little time before Wallace, encircled by a group of male spectators, was enabled to change his costume; and during the interval he continued to stand waist-deep in the water, to the chagrin of various couples who came to the tee in the course of their round and complained with not a little bitterness that his presence there added a mental hazard to an already difficult hole. Eventually, however, he found himself back ashore, his ball before him, his mashie in his hand.

“Carry on,” said Peter Willard, as the couple in front left the green. “All clear now.”

Wallace Chesney addressed his ball. And, even as he did so, he was suddenly aware that an odd psychological change had taken place in himself. He was aware of a strange weakness. The charred remains of the Plus Fours were lying under an adjacent bush; and, clad in the old grey flannels of his early golfing days, Wallace felt diffident, feeble, uncertain of himself. It was as though virtue had gone out of him, as if some indispensable adjunct to good play had been removed. His corrugated trouser-leg caught his eye as he waggled, and all at once he became acutely alive to the fact that many eyes were watching him. The audience seemed to press on him like a blanket. He felt as he had been wont to feel in the old days when he had had to drive off the first tee in front of a terrace-full of scoffing critics.

The next moment his ball had bounded weakly over the intervening patch of turf and was in the water.

“Hard luck!” said Peter Willard, ever a generous foe. And the words seemed to touch some almost atrophied chord in Wallace’s breast. A sudden love for his species flooded over him. Dashed decent of Peter, he thought, to sympathize. Peter was a good chap. So were the spectators good chaps. So was everybody, even his caddie.

Peter Willard, as if resolved to make his sympathy practical, also rolled his ball into the lake.

“Hard luck!” said Wallace Chesney, and started as he said it; for many weeks had passed since he had commiserated with an opponent. He felt a changed man. A better, sweeter, kindlier man. It was as if a curse had fallen from him.

He teed up another ball, and swung.

“Hard luck!” said Peter.

“Hard luck!” said Wallace, a moment later.

“Hard luck!” said Peter, a moment after that.

Wallace Chesney stood on the tee watching the spot in the water where his third ball had fallen. The crowd was now openly amused, and, as he listened to their happy laughter, it was borne in upon Wallace that he, too, was amused and happy. A weird, almost effervescent exhilaration filled him. He turned and beamed upon the spectators. He waved his mashie cheerily at them. This, he felt, was something like golf. This was golf as it should be—not the dull, mechanical thing which had bored him during all these past weeks of his perfection, but a gay, rollicking adventure. That was the soul of golf, the thing that made it the wonderful pursuit it was—that speculativeness, that not knowing where the dickens your ball was going when you hit it, that eternal hoping for the best, that never-failing chanciness. It is better to struggle hopefully than to arrive, and at last this great truth had come home to Wallace Chesney. He realized now why pro’s were all grave, silent men who seemed to struggle manfully against some secret sorrow. It was because they were too darned good. Golf had no surprises for them, no gallant spirit of adventure.

“I’m going to get a ball over if I stay here all night,” cried Wallace Chesney, gaily, and the crowd echoed his mirth. On the face of Charlotte Dix was the look of a mother whose prodigal son has rolled into the old home once more. She caught Wallace’s eyes and gesticulated to him blithely.

“The cripple says he’ll give you a stroke a hole, Wally!” she shouted.

“I’m ready for him!” bellowed Wallace.

“Hard luck!” said Peter Willard.

UNDER their bush the Plus Fours, charred and dripping, lurked unnoticed. But Wallace Chesney saw them. They caught his eye as he sliced his eleventh into the marshes on the right. It seemed to him that they looked sullen. Disappointed. Baffled.

Wallace Chesney was himself again.

Note:

Our detailed annotations are appended to the Red Book appearance of the story, titled merely “The Plus Fours.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums