Vanity Fair, March 1915

SCOOTERIN’: HALF SAILING, HALF ICE-BOATING

By P. G. Wodehouse

LIKE so many other pastimes, Scooterin’ did not start its career with the idea of being a pastime at all. Its original idea was a purely utilitarian one. This frequently happens in the world of sport.

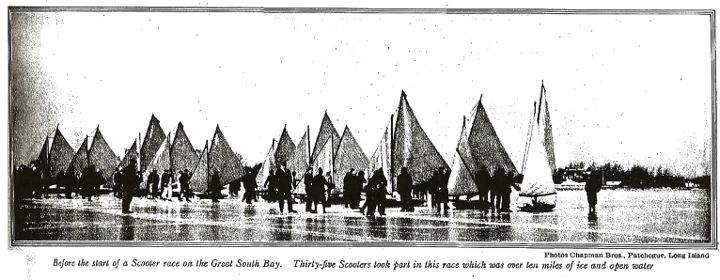

Tue first men to Scooter did it, not because they wanted to be exhilarated by the movement, but because they wanted to get from one place to another. They were the various groups of life-savers on the beach which bounds the ocean side of the Great South Bay, and they found it impossible to get over to the mainland in winter for supplies owing to the danger from the ice-holes in the bay. With a touch of natural genius, they put a pair of runners on the bottom of their boats. The boats whizzed across the ice, plunged into a hole, and, instead of being at all discommoded by the hole, behaved better in the water than on the ice.

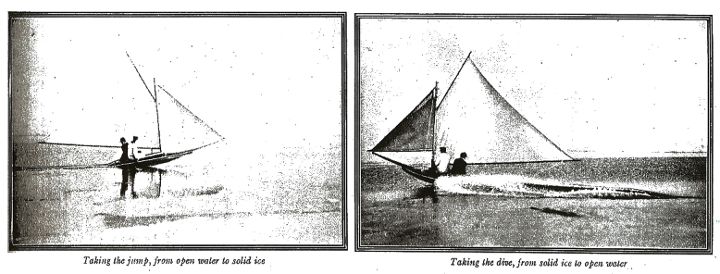

And therein lies the charm of Scooterin’, that it is at its best when the ice has holes in it, for the pleasurable sensation comes from the abrupt change from ice to water and from water to ice—a sensation somewhat resembling that obtained by “shooting the chutes” at Coney Island. It is this that makes your Scooterer laugh a sharp, derisive laugh, when you say to him that you “suppose that Scooterin’ is really just the same as ice-boating, isn’t it?” In an eloquent burst he will point out that Scooterin’ has it over ice-boating in a dozen ways, which he will proceed specifically to name.

For one thing it’s cheaper—as a good Scooter boat costs only $100. You have to steer a Scooter entirely by the jib. It takes two or three persons to work it properly, and some thing of a Polar bear or an Arctic explorer to enjoy it on a really cold day.

When the hardy Scooter rises from his couch on a February morning and finds the water frozen in his bedroom pitcher, and, putting his head out of doors, is nearly decapitated by a razor-like wind blowing from the east, he says to himself, “It’s a hanged fine day. I’ll go Scooterin’.” So he trots off to the partly frozen lake or bay, collects a few friends, and gets out his boat. And presently they are flying across the ice at the pace of a racing automobile. Soon they come to a spot where the ice has melted and left a watery gap. The Scooter boat does not even hesitate. It skims across the gap like a duck, and goes about its lawful occupations on the other side as if nothing had happened. And then the wind drops suddenly, or shifts, and the boat goes round in circles, while he at the tiller shouts unintelligible directions to one of his passengers to shift his weight to one side, or not to shift his weight to one side, or to do something which he is not doing, or not to do something which he is doing. And the passenger, by now a chunk of solid ice, tries to thaw his frozen senses sufficiently to do what he is told to do or not to do what he is told not to do. And somewhere, deep down in him, a voice is whispering, “About now, you poor deluded nut, if you hadn’t come Scooterin’, you would be sitting down to a nice, hot breakfast in front of your fire.”

I hold no brief for or against Scooterin’. If the public likes to rush to lakes and rivers and bays and start Scooterin’, by all means let it so rush and Scooter: but let it be clearly understood that I, though advertising this weird pastime in this esteemed paper, will not often be dragged from my warm fireside to participate in it.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums