Vanity Fair, October 1914

IT has never been clearly decided whether English country-house life came into being to keep the English playwright from the bread-line, or whether the playwright owes his existence to the country-house. The only thing certain is that, if there had been no country-houses, many deserving dramatists would have had to get right out and work.

The thoughtful visitor, coming away from an English country-house, cannot resist the feeling that, as soon as he has got out of sight, they will “strike the scene.” His late host will take off his whiskers and go off to talk politics with the butler: the ingenue, to whom he so nearly proposed last night, will change her dress and go out to supper: while the stage hands pull down the fine old mansion, the rose-garden, and the terrace, and store them in a shed ready for the next production.

The whole atmosphere is of the stage. You enter (r. c.) through the front door onto a “hall scene.” Various characters are scattered about “gracefully drinking tea.” In the background, Jakes, the faithful butler. Your hostess comes forward and speaks a line: you reply: and from that moment you become part of the action of the piece. Not until you are in the train that is bearing you to London do you shake off the stage effect.

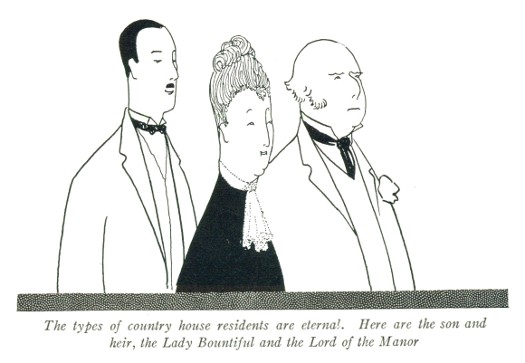

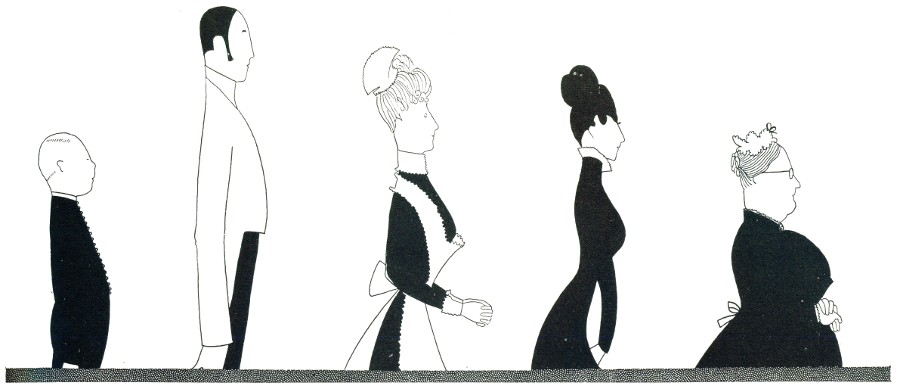

It is the fault of the dramatists, in all probability. You have seen so many plays, the third act of which took place in the hall of Sir Raymond Prothero’s country-house in Shropshire, that you cannot get away from the thing. The country-house fascinates the dramatist, principally because it is the one atmosphere in which he cannot make a mistake. All country-houses are alike, always have been alike, and always will be alike. The types of residents and visitors are eternal. There is the Lord of the Manor, smooth-faced but wearing small whiskers: the Lady Bountiful, mild and aristocratic, with her hair preceding her in a neat bun on the road to Heaven: the Son and Heir, the catch of the county, smooth-haired, reserved, almost meek. He knows his value, but he will not let himself get puffed up about it.

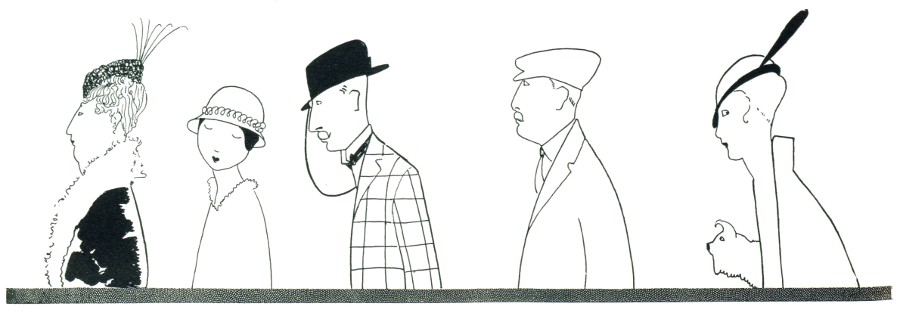

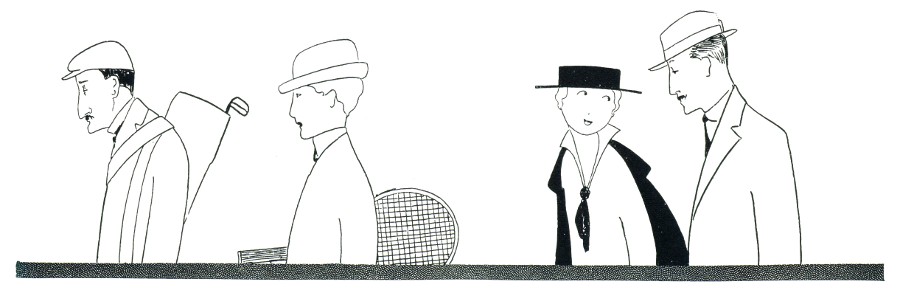

NEXT the Guests. The sad-faced golfer, the stern tennis-player, the terrace-haunting sentimentalists, the mother with daughter, the smart lady with dog, and—most important of all, the Colonel.

He is nearly always a colonel, unless he is a major. If he is a civilian, he owns property in Wales. But he is hardly ever a civilian. It seems to be almost a rule that the Permanent Guest should be connected with the military. He, more even than the butler, helps to establish that air of peace which is the key-note of the atmosphere of the country-house. On the stage he is sometimes a barrister or a Cabinet Minister, and his duty is to be the Man Who Keeps His Head, the Man Who Knows The World, the Man Who Has The Fatherly Scene with the Heroine. Her husband does not understand her: she has temperament, he merely exists for sport: she is going to run away with the young man with the black hair brushed back over his head. And then she collides with this gentle, kindly, cynical, understanding man with the strong face, and he talks to her. After he has talked to her for twenty minutes or so, she feels that her husband isn’t so bad after all, and so you get the happy ending. He also detects adventuresses.

The servants are comic relief.

To a thinking man, there is something a little eerie about the country-house. What is there in its atmosphere that makes everybody so exactly alike? The stage explanation is the only one that satisfies the intellect. If the country-house is not a stage set, how can one explain the fact that people who in London are individuals become types as soon as they have passed its portals? This is not a wild statement: it can be supported by evidence. Each week throughout the year the London illustrated papers print country-house “groups.” Each group is exactly the same as every other group. The editor could substitute the “interesting picture of the house-party at Weevils, the Hampshire seat of Lord Maxted” for “some familiar faces at the shoot at Blore Manor, Herts,” without anybody noticing the change, not even the people in the photographs. Yet in London each of these persons has a distinct individuality of his or her own, and would be offended at the suggestion that he or she could be taken for somebody else.

THAT is why the country-house is so restful. Your private troubles fade as you enter it: the world seems very far away: you have nothing to think of except the part for which you have been cast. Off stage, you are a man with pronounced views on a variety of different subjects: once in the country-house, you become a mere inspector of horses, a prodder of pigs, an unnoticed unit at the breakfast-table.

Progress, flooding the land, has but trickled over the country-house. The carriage has given place to the automobile, and that is all. All the grand old beliefs still flourish,—chiefly the belief that one bath-room is enough for thirty people. England’s greatness is based on this belief. If England once got the idea that there is any other way for a man to clean himself than in a round tin saucer filled to the brim with an inch and a half of water, good-bye to Empire. Waterloo was won on the playing-fields of Eton, the Boer War in the bachelor bedrooms of England’s country-houses. Hardened by their privations at Woosted Beeches, Salop, and The Oaks, Northants, the gentlemen of England were ready for anything that came along. If they had to go days on end without a sight of water, they said to themselves, “Well, it might be worse. We might be spending the week-end somewhere and chasing the soap round the tin saucer on a cold morning!”

That is the spirit which wins battles.

It has always been a mystery to me what are the qualifications which admit you to the One Bath-Room. To me it has always been a kind of Pisgah. I have heard it talked about, and I have even seen it: but I have never been there. For me the tin saucer and the inch and a half of water. Perhaps it is reserved as a graceful mark of reverence for Age. Certainly, the lucky devils I have met on their way there with dressing-gowns and sponges have always been elderly men of the retired general or colonel type. And even they have their troubles. They have to bathe to schedule. Five minutes’ delay between the sheets, and the colonel’s tub is spoilt by the frenzied snorts of impatience and anger from the general, entrenched in the passage, waiting his turn. This time-sheet business leads, too, to occasional embarrassment, as when the hostess said to the honored guest, ‘When would you like your bath in the morning?’ and he replied, ‘My time is your time, Mrs. Brown.’

THE lack of bathing facilities is not the only drawback to country-house visiting. Indeed, the keynote of the country-house may be said to be a kind of luxurious discomfort. The average party consists of people fifty percent of whom are meeting each other for the first time: they have from Friday or Saturday evening to Monday morning to get acquainted. This is about two years eleven months and a few days less than the minimum period in which the average Briton can get acquainted with anyone. An air of restraint broods over the gathering. Good-fellowship exists in patches, but the bulk of the temporary population of the house has the tense demeanour of those who have set themselves a task and mean to fulfil it. They have contracted to stay till Monday morning, and they mean to do it; but it is too much to expect them to do it rollickingly. I have seen week-enders at country-houses, who probably had no notion that they were not the life and soul of the party, pottering about in a dejected way that would have caused comment in a Siberian salt-mine. There seems to be no escape from this frame of mind. If your host is one of those hosts who believe in letting guests alone to amuse themselves, the probability is that the guests, being of the class who are not strong in the way of mental resources, will be passively bored. The active host, on the other hand, who hounds his guests and insists on their doing something all the time, whether they like it or not, is an active evil. It is a hard world.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums