Vanity Fair, June 1916

THE NEW GAME OF MENTAL GOLF

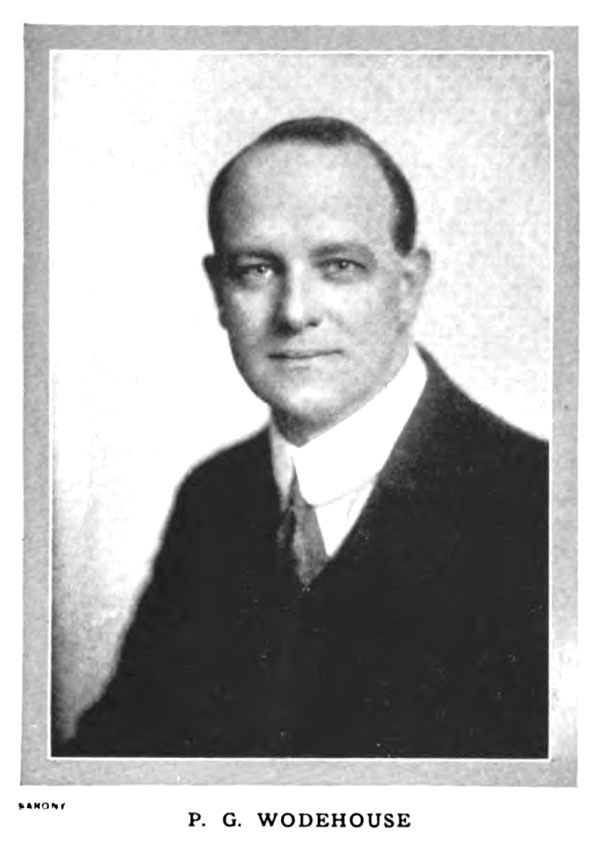

In His New Novel, Mr. P. G. Wodehouse Reveals a Valuable Discovery

IT is a well-established scientific fact that no woman is ever on time in keeping an appointment. If she is to meet her host at Delmonico’s at one-thirty, she arrives at two. If the tryst is for two o’clock at the Ritz-Carlton, she appears at half-past. Man has accordingly been at considerable pains to hit on some satisfactory method of passing those inevitable minutes of waiting, but until recently without much success. The ingenuity of the average man stops short at smoking a cigarette or drinking a cocktail, though cases have been known of intellectuals who have whiled the moments away by reading pocket editions of the poets. It has been left for William FitzWilliam Delamere Chalmers, Lord Dawlish, to solve the problem in the only really satisfactory way. Lord Dawlish is the hero of Mr. Pelham Grenville Wodehouse’s latest novel, “Uneasy Money,” and we are introduced to him at the moment when he is waiting for his fiancée, Claire Fenwick, outside the Bandolero Restaurant, where she has arranged to lunch with him. Claire, of course, was late: and, as Lord Dawlish stood there, “his mouth was set and his eyes wore a serious, almost a wistful expression. He was frowning slightly.” Was he growing impatient? Not so. He was merely thinking what was the best method of laying a golf ball dead from where he stood in front of the Palace Theater. His was a simple mind, able to amuse itself with simple pleasures, and it was his habit to pass the time in mental golf when Claire Fenwick was late in keeping her appointments with him.

Mr. Wodehouse has invented a really excellent pastime. Take any street, any square, any series of public buildings, and, if you are a true golfer, figure out for yourself the par, or the bogie even, from any restaurant to any church, or any bank to any cabaret. Why not a whole round of the links—eighteen holes, for instance—from the entrance to the subway in front of the Knickerbocker Grill at Forty-second Street to the cab-stand in front of Bustanoby’s—all bars on the way to be considered as hazards.

Mr. Wodehouse, in addition to inventing Mental Golf, has created a figure unique in fiction—an impecunious English peer who courts and marries an impecunious American girl and for whom money has so little attraction that, when he does get some, he spends three hundred and twenty-six pages trying to give it away.

Three hundred and twenty-six pages in which a gift of humor and a gift of story-telling fight on every page with a swift and certain gift for character drawing.

THERE is, in “Uneasy Money,” as in most of Mr. Wodehouse’s writings, a hideous fascination. One might almost call him the cobra di capello among the fiction writers of our day. Readers of his stories frequently become—to carry out the shuddery analogy—like the little yellow and white guinea pigs who cower and tremble in corners of their cages, hypnotized by the rhythmic and horrible mental convolutions of the man. He has a habit of talking, oh, so soothingly, about nothing at all, for pages and pages, but he does it in such an underhanded way that you simply cannot take your eye off him lest some disaster should befall:—a hiss from his typewriter, for instance, or a ruby, darting lightning-swift fang from his fountain pen.