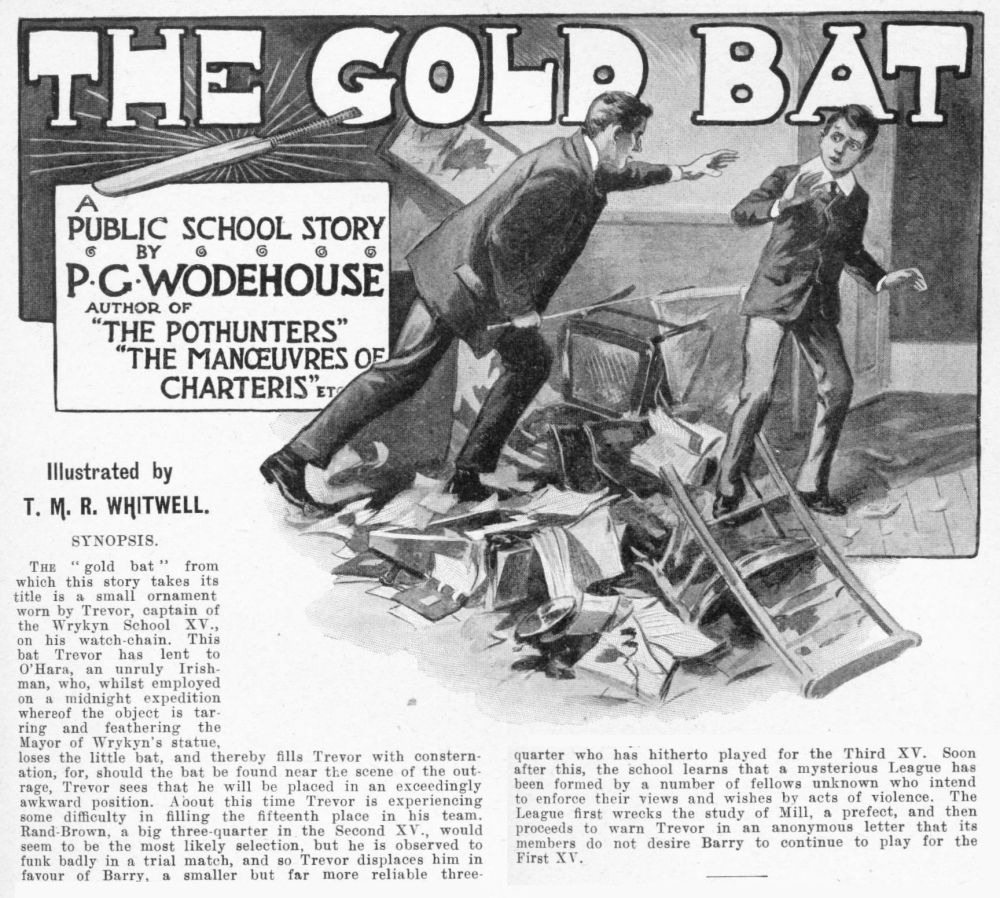

The Captain, November 1903

CHAPTER V.

Mill Receives Visitors.

REVOR’S

first idea was that somebody had sent the letter for a joke. Clowes for

choice.

REVOR’S

first idea was that somebody had sent the letter for a joke. Clowes for

choice.

He sounded him on the subject after breakfast.

“Did you send me that letter?” he enquired, when Clowes came into his study to borrow a Sportsman.

“What letter? Did you send the teams for to-morrow up to the sporter? I wonder what sort of a lot the town are bringing.”

“About not giving Barry his footer colours?”

Clowes was reading the paper.

“Giving whom?” he asked.

“Barry. Can’t you listen?”

“Giving him what?”

“Footer colours.”

“What about them?”

Trevor sprang at the paper, and tore it away from him. After which he sat on the fragments.

“Did you send me a letter about not giving Barry his footer colours?”

Clowes surveyed him with the air of a nurse to whom the family baby has just said some more than usually good thing.

“Don’t stop,” he said, “I could listen all day.”

Trevor felt in his pocket for the note, and flung it at him. Clowes picked it up, and read it gravely.

“What are footer colours?” he asked.

“Well,” said Trevor, “it’s a pretty rotten sort of joke, whoever sent it. You haven’t said yet whether you did or not.”

“What earthly reason should I have for sending it? And I think you’re making a mistake if you think this is meant as a joke.”

“You don’t really believe this League rot?”

“You didn’t see Mill’s study ‘after treatment.’ I did. Anyhow, how do you account for the card I showed you?”

“But that sort of thing doesn’t happen at school.”

“Well, it has happened, you see.”

“Who do you think did send the letter, then?”

“The president of the League.”

“And who the dickens is the president of the League when he’s at home?”

“If I knew that, I should tell Mill, and earn his blessing. Not that I want it.”

“Then, I suppose,” snorted Trevor, “you’d suggest that on the strength of this letter, I’d better leave Barry out of the team?”

“Satirically in brackets,” commented Clowes.

“It’s no good your jumping on me,” he added. “I’ve done nothing. All I suggest is that you’d better keep more or less of a look-out. If this League’s anything like the old one, you’ll find they’ve all sorts of ways of getting at people they don’t love. I shouldn’t like to come down for a bath some morning, and find you already in possession, tied up like Robinson. When they found Robinson, he was quite blue both as to the face and speech. He didn’t speak very clearly, but what one could catch was well worth hearing. I should advise you to sleep with a loaded revolver under your pillow.”

“The first thing I shall do is find out who wrote this letter.”

“I should,” said Clowes, encouragingly. “Keep moving.”

In Seymour’s house the Mill’s study incident formed the only theme of conversation that morning. Previously the sudden elevation to the first fifteen of Barry, who was popular in the house, at the expense of Rand-Brown, who was unpopular, had given Seymour’s something to talk about. But the ragging of the study put this topic entirely in the shade. The study was still on view in almost its original condition of disorder, and all day comparative strangers flocked to see Mill in his den, in order to inspect things. Mill was a youth with few friends, and it is probable that more of his fellow-Seymourites crossed the threshold of his study on the day after the occurrence than had visited him in the entire course of his school career. Brown would come in to borrow a knife, would sweep the room with one comprehensive glance, and depart, to be followed at brief intervals by Smith, Robinson, and Jones, who came respectively to learn the right time, to borrow a book, and to ask him if he had seen a pencil anywhere. Towards the end of the day, Mill would seem to have wearied somewhat of the proceedings, as was proved when Master Thomas Renford, aged fourteen (who fagged for Milton, the head of the house), burst in on the thin pretence that he had mistaken the study for that of his rightful master, and gave vent to a prolonged whistle of surprise and satisfaction at the sight of the ruins. On that occasion the incensed owner of the dismantled study, taking a mean advantage of the fact that he was a prefect, and so entitled to wield the rod, produced a handy swagger-stick from an adjacent corner, and, inviting Master Renford to bend over, gave him six of the best to remember him by. Which ceremony being concluded, he kicked him out into the passage, and Renford went down to the junior day-room to tell his friend Harvey about it.

“Gave me six, the cad,” said he, “just because I had a look at his beastly study. Why shouldn’t I look at his study if I like! I’ve a jolly good mind to go up and have another squint.”

Harvey warmly approved the scheme.

“No, I don’t think I will,” said Renford with a yawn. “It’s such a fag going upstairs.”

“Yes, isn’t it?” said Harvey.

“And he’s such a beast, too.”

“Yes, isn’t he?” said Harvey.

“I’m jolly glad his study has been ragged,” continued the vindictive Renford.

“It’s jolly exciting, isn’t it?” added Harvey. “And I thought this term was going to be slow. The Easter term generally is.”

This remark seemed to suggest a train of thought to Renford, who made the following cryptic observation. “Have you seen them to-day?”

To the ordinary person the words would have conveyed little meaning. To Harvey they appeared to teem with import.

“Yes,” he said, “I saw them early this morning.”

“Were they all right?”

“Yes. Splendid.”

“Good,” said Renford.

Barry’s friend Drummond was one of those who had visited the scene of the disaster early, before Mill’s energetic hand had repaired the damage done, and his narrative was consequently in some demand.

“The place was in a frightful muck,” he said. “Everything smashed except the table. And ink all over the place. Whoever did it must have been fairly sick with him, or he’d never have taken the trouble to do it so thoroughly. Made a fair old hash of things, didn’t he, Bertie?”

“Bertie” was the form in which the school elected to serve up the name of De Bertini. Raoul de Bertini was a French boy who had come to Wrykyn in the previous term. Drummond’s father had met his father in Paris, and Drummond was supposed to be looking after Bertie. They shared a study together. Bertie could not speak much English, and what he did speak was, like Mill’s furniture, badly broken.

“Pardon?” he said.

“Doesn’t matter,” said Drummond, “it wasn’t anything important. I was only appealing to you for corroborative detail to give artistic verisimilitude to a bald and unconvincing narrative.”

Bertie grinned politely. He always grinned when he was not quite equal to the intellectual pressure of the conversation. As a consequence of which, he was generally, like Mrs Fezziwig, one vast, substantial smile.

“I never liked Mill much,” said Barry. “But I think it’s rather bad luck on the man.”

“Once,” announced McTodd, solemnly, “he kicked me—for making a row in the passage.” It was plain that the recollection rankled.

Barry would probably have pointed out what an excellent and praiseworthy act on Mill’s part that had been, when Rand-Brown came in.

“Prefects’ meeting?” he inquired. “Or haven’t they made you a prefect yet, McTodd?”

McTodd said they had not.

Nobody present liked Rand-Brown, and they looked at him rather enquiringly, as if to ask what he had come for. A friend may drop in for a chat. An acquaintance must justify his intrusion.

Rand-Brown ignored the silent enquiry. He seated himself on the table, and dragged up a chair to rest his legs on.

“Talking about Mill, of course?” he said.

“Yes,” said Drummond. “Have you seen his study since it happened?”

“Yes.”

Rand-Brown smiled, as if the recollection amused him. He was one of those people who do not look their best when they smile.

“Playing for the first to-morrow, Barry?”

“I don’t know,” said Barry, shortly. “I haven’t seen the list.”

He objected to the introduction of the topic. It is never pleasant to have to discuss games with the very man one has ousted from the team.

Drummond, too, seemed to feel that the situation was an embarrassing one, for a few minutes later he got up to go over to the gymnasium.

“Any of you chaps coming?” he asked.

Barry and McTodd thought they would, and the three left the room.

“Nothing like showing a man you don’t want him, eh, Bertie? What do you think?” said Rand-Brown.

Bertie grinned politely.

CHAPTER VI.

Trevor Remains Firm.

MOST immediate effect of telling anybody not to do a thing is to make him do

it, in order to assert his independence. Trevor’s first act on receipt of

the letter was to include Barry in the team against the town. It was what

he would have done in any case, but, under the circumstances, he felt a

peculiar pleasure in doing it. The incident also had the effect of

recalling to his mind the fact that he had tried Barry in the first instance on

his own responsibility, without consulting the committee. The committee

of the first fifteen consisted of the two old colours who came immediately

after the captain on the list. The powers of a committee varied according

to the determination and truculence of the members of it. On any definite

and important step, affecting the welfare of the fifteen, the captain

theoretically could not move without their approval. But if the captain

happened to be strong-minded and the committee weak, they were apt to be

slightly out of it, and the captain would develop a habit of consulting them a

day or so after he had done a thing. He would give a man his colours, and

inform the committee of it on the following afternoon, when the thing was done

and could not be repealed.

MOST immediate effect of telling anybody not to do a thing is to make him do

it, in order to assert his independence. Trevor’s first act on receipt of

the letter was to include Barry in the team against the town. It was what

he would have done in any case, but, under the circumstances, he felt a

peculiar pleasure in doing it. The incident also had the effect of

recalling to his mind the fact that he had tried Barry in the first instance on

his own responsibility, without consulting the committee. The committee

of the first fifteen consisted of the two old colours who came immediately

after the captain on the list. The powers of a committee varied according

to the determination and truculence of the members of it. On any definite

and important step, affecting the welfare of the fifteen, the captain

theoretically could not move without their approval. But if the captain

happened to be strong-minded and the committee weak, they were apt to be

slightly out of it, and the captain would develop a habit of consulting them a

day or so after he had done a thing. He would give a man his colours, and

inform the committee of it on the following afternoon, when the thing was done

and could not be repealed.

Trevor was accustomed to ask the advice of his lieutenants fairly frequently. He never gave colours, for instance, off his own bat. It seemed to him that it might be as well to learn what views Milton and Allardyce had on the subject of Barry, and, after the town team had gone back across the river defeated by a goal and a try to nil, he changed and went over to Seymour’s to interview Milton.

Milton was in an arm-chair, watching Renford brew tea. His was one of the few studies in the school in which there was an arm-chair. With the majority of his contemporaries it would only run to the portable kind that fold up.

“Come and have some tea, Trevor,” said Milton.

“Thanks. If there’s any going.”

“Heaps. Is there anything to eat, Renford?”

The fag, appealed to on this important point, pondered darkly for a moment.

“There was some cake,” he said.

“That’s all right,” interrupted Milton, cheerfully. “Scratch the cake. I ate it before the match. Isn’t there anything else?”

Milton had a healthy appetite.

“Then there used to be some biscuits.”

“Biscuits are off. I finished ’em yesterday. Look here, young Renford, what you’d better do is cut across to the shop and get some more cake and some more biscuits, and tell ’em to put it down to me. And don’t be long.”

“A miles better idea would be to send him over to Donaldson’s to fetch something from my study,” suggested Trevor. “It isn’t nearly so far, and I’ve got heaps of stuff.”

“Ripping. Cut over to Donaldson’s, young Renford. As a matter of fact,” he added, confidentially, when the emissary had vanished, “I’m not half sure that the other dodge would have worked. They seem to think at the shop that I’ve had about enough things on tick lately. I haven’t settled up for last term yet. I’ve spent all I’ve got on this study. What do you think of those photographs?”

Trevor got up and inspected them. They filled the mantelpiece and most of the wall above it. They were exclusively theatrical photographs, and of a variety to suit all tastes. For the earnest student of the drama there was Sir Henry Irving in The Bells, and Mr. Martin Harvey in The Only Way. For the admirers of the merely beautiful there were Messrs. Dan Leno and Herbert Campbell.

“Not bad,” said Trevor. “Beastly waste of money.”

“Waste of money!” Milton was surprised and pained at the criticism. “Why, you must spend your money on something.”

“What’s the good of them?” enquired Trevor.

“That reminds me of a story a chap told me at camp last year. The headmaster of his school had gone up to Oxford to see some of the Old Boys there. The first man he called on was a chap of the name of O’Flynn. ‘How do you do, O’Flynn?’ he said. ‘How do you do, sir?’ said O’Flynn. Then he looked round the room. The first thing he saw was a large photograph of some actress or other. The next thing he saw was a still larger photograph of the same lady. After that he made a tour of the room in dead silence. There were nineteen of the photographs altogether. ‘Do you find it necessary to have all these photographs, O’Flynn?’ he said. ‘Yes, sir,’ said O’Flynn. ‘Good-bye, O’Flynn,’ said the headmaster. And he went, and has never been near him since.”

“Rot, I call it,” said Trevor. “If you want to collect something, why don’t you collect something worth having?”

Just then Renford came back with the supplies.

“Thanks,” said Milton, “put ’em down. Does the billy boil, young Renford?”

Renford asked for explanatory notes.

“You’re a bit of an ass at times, aren’t you?” said Milton kindly. “What I meant was, is the tea ready? If it is, you can scoot. If it isn’t, buck up with it.”

A sound of bubbling and a rush of steam from the spout of the kettle proclaimed that the billy did boil. Renford extinguished the Etna, and left the room, while Milton, murmuring vague formulæ about “one spoonful for each person and one for the pot,” got out of his chair with a groan—for the town match had been an energetic one—and began to prepare tea.

“What I really came round about——” began Trevor.

“Half a second. I can’t find the milk.”

He went to the door, and shouted for Renford. On that overworked youth’s appearance the following dialogue took place.

“Where’s the milk?”

“What milk?”

“My milk.”

“There isn’t any.” This in a tone not untinged with triumph, as if the speaker realised that here was a distinct score to him.

“No milk?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“You never had any.”

“Well, just cut across—no, half a second. What are you doing downstairs?”

“Having tea.”

“Then you’ve got milk.”

“Only a little.” This apprehensively.

“Bring it up. You can have what we leave.”

Disgusted retirement of Master Renford.

“What I really came about,” said Trevor again, “was business.”

“Colours?” inquired Milton, rummaging in the tin for biscuits with sugar on them. “Good brand of biscuit you keep, Trevor.”

“Yes. I think we might give Alexander and Parker their third.”

“All right. Any others?”

“Barry his second, do you think?”

“Rather. He played a good game to-day. He’s an improvement on Rand-Brown.”

“Glad you think so. I was wondering whether it was the right thing to do, chucking Rand-Brown out after one trial like that. But still, if you think Barry’s better——”

“Streets better. I’ve had heaps of chances of watching them, and comparing them, when they’ve been playing for the house. It isn’t only that Rand-Brown can’t tackle, and Barry can. Barry takes his passes much better, and doesn’t lose his head when he’s pressed.”

“Just what I thought,” said Trevor. “Then you’d go on playing him for the first?”

“Rather. He’ll get better every game, you’ll see, as he gets more used to playing in the first three-quarter line. And he’s as keen as anything on getting into the team. Practises taking passes and that sort of thing every day.”

“Well, he’ll get his colours if we lick Ripton.”

“We ought to lick them. They’ve lost one of their forwards, Clifford, a red-haired chap, who was good out of touch. I don’t know if you remember him.”

“I suppose I ought to go and see Allardyce about these colours, now. Good-bye.”

There was running and passing on the Monday for every one in the three teams. Trevor and Clowes met Mr. Seymour as they were returning. Mr. Seymour was the football master at Wrykyn.

“I see you’ve given Barry his second, Trevor.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I think you’re wise to play him for the first. He knows the game, which is the great thing, and he will improve with practice,” said Mr. Seymour, thus corroborating Milton’s words of the previous Saturday.

“I’m glad Seymour thinks Barry good,” said Trevor, as they walked on. “I shall go on playing him now.”

“Found out who wrote that letter yet?”

Trevor laughed.

“Not yet,” he said.

“Probably Rand-Brown,” suggested Clowes. “He’s the man who would gain most by Barry’s not playing. I hear he had a row with Mill just before his study was ragged.”

“Everybody in Seymour’s has had rows with Mill some time or other,” said Trevor.

Clowes stopped at the door of the junior day-room to find his fag. Trevor went on upstairs. In the passage he met Ruthven.

Ruthven seemed excited.

“I say, Trevor,” he exclaimed, “have you seen your study?”

“Why, what’s the matter with it?”

“You’d better go and look.”

CHAPTER VII.

“With the Compliments of the League”

REVOR

went and looked.

REVOR

went and looked.

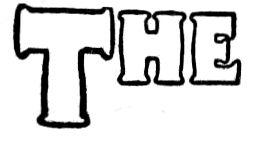

It was rather an interesting sight. An earthquake or a cyclone might have made it a little more picturesque, but not much more. The general effect was not unlike that of an American saloon, after a visit from Mrs. Carrie Nation (with hatchet). As in the case of Mill’s study, the only thing that did not seem to have suffered any great damage was the table. Everything else looked rather off colour. The mantelpiece had been swept as bare as a bone, and its contents littered the floor. Trevor dived among the débris and retrieved the latest addition to his art gallery, the photograph of this year’s first fifteen. It was a wreck. The glass was broken and the photograph itself slashed with a knife till most of the faces were unrecognisable. He picked up another treasure, last year’s first eleven. Smashed glass again. Faces cut about with knife as before. His collection of snapshots was torn into a thousand fragments, though, as Mr. Jerome said of the papier-mâché trout, there may only have been nine hundred. He did not count them. His bookshelf was empty. The books had gone to swell the contents of the floor. There was a Shakespeare with its cover off. Pages twenty-two to thirty-one of Vice Versâ had parted from the parent establishment, and were lying by themselves near the door. The Rogues’ March lay just beyond them, and the look of the cover suggested that somebody had either been biting it or jumping on it with heavy boots.

There was other damage. Over the mantelpiece in happier days had hung a dozen sea gulls’ eggs, threaded on a string. The string was still there, as good as new, but of the eggs nothing was to be seen, save a fine parti-coloured powder—on the floor, like everything else in the study. And a good deal of ink had been upset in one place and another.

Trevor had been staring at the ruins for some time, when he looked up to see Clowes standing in the doorway.

“Hullo,” said Clowes, “been tidying up?”

Trevor made a few hasty comments on the situation. Clowes listened approvingly.

“Don’t you think,” he went on, eyeing the study with a critical air, “that you’ve got too many things on the floor, and too few anywhere else? And I should move some of those books on to the shelf, if I were you.”

Trevor breathed very hard.

“I should like to find the chap who did this,” he said softly.

Clowes advanced into the room and proceeded to pick up various misplaced articles of furniture in a helpful way.

“I thought so,” he said, presently, “come and look here.”

Tied to a chair, exactly as it had been in the case of Mill, was a neat white card, and on it were the words, “With the Compliments of the League.”

“What are you going to do about this?” asked Clowes. “Come into my room and talk it over.”

“I’ll tidy this place up first,” said Trevor. He felt that the work would be a relief. “I don’t want people to see this. It mustn’t get about. I’m not going to have my study turned into a sort of side-show, like Mill’s. You go and change. I sha’n’t be long.”

“I will never desert Mr. Micawber,” said Clowes. “Friend, me place is by your side. Shut the door and let’s get to work.”

Ten minutes later the room had resumed a more or less—though principally less—normal appearance. The books and chairs were back in their places. The ink was sopped up. The broken photographs were stacked in a neat pile in one corner, with a rug over them. The mantelpiece was still empty, but, as Clowes pointed out, it now merely looked as if Trevor had been pawning some of his household gods. There was no sign that a devastating secret society had raged through the study.

Then they adjourned to Clowes’ study, where Trevor sank into Clowes’ second-best chair—Clowes, by an adroit movement, having appropriated the best one—with a sigh of enjoyment. Running and passing, followed by the toil of furniture-shifting, had made him feel quite tired.

“It doesn’t look so bad now,” he said, thinking of the room they had left. “By the way, what did you do with that card?”

“Here it is. Want it?”

“You can keep it. I don’t want it.”

“Thanks. If this sort of things goes on, I shall get quite a nice collection of these cards. Start an album some day.”

“You know,” said Trevor, “this is getting serious.”

“It always does get serious when anything bad happens to one’s self. It always strikes one as rather funny when things happen to other people. When Mill’s study was wrecked, I bet you regarded it as an amusing and original ‘turn.’ What do you think of the present effort?”

“Who on earth can have done it?”

“The Pres——”

“Oh, dry up. Of course it was. But who the blazes is he?”

“Nay, children, you have me there,” quoted Clowes. “I’ll tell you one thing, though. You remember what I said about it’s probably being Rand-Brown. He can’t have done this, that’s certain, because he was out in the fields the whole time. Though I don’t see who else could have anything to gain by Barry not getting his colours.”

“There’s no reason to suspect him at all, as far as I can see. I don’t know much about him, bar the fact that he can’t play footer for nuts, but I’ve never heard anything against him. Have you?”

“I scarcely know him myself. He isn’t liked in Seymour’s, I believe.”

“Well, anyhow, this can’t be his work.”

“That’s what I said.”

“For all we know, the League may have got their knife into Barry for some reason. You said they used to get their knife into fellows in that way. Anyhow, I mean to find out who ragged my room.”

“It wouldn’t be a bad idea,” said Clowes.

O’Hara came round to Donaldson’s before morning school next day to tell Trevor that he had not yet succeeded in finding the lost bat. He found Trevor and Clowes in the former’s den, trying to put a few finishing touches to the same.

“Hullo, an’ what’s up with your study?” he inquired. He was quick at noticing things. Trevor looked annoyed. Clowes asked the visitor if he did not think the study presented a neat and gentlemanly appearance.

“Where are all ye’re photographs, Trevor?” persisted the descendant of Irish kings.

“It’s no good trying to conceal anything from the bhoy,” said Clowes. “Sit down, O’Hara—mind that chair; it’s rather wobbly—and I will tell ye the story.”

“Can you keep a thing dark?” enquired Trevor.

O’Hara protested that tombs were not in it.

“Well, then, do you remember what happened to Mill’s study? That’s what’s been going on here.”

O’Hara nearly fell off his chair with surprise. That some philanthropist should rag Mill’s study was only to be expected. Mill was one of the worst—a worm without a saving grace. But Trevor! Captain of football! In the first eleven! The thing was unthinkable.

“But who——?” he began.

“That’s just what I want to know,” said Trevor, shortly. He did not enjoy discussing the affair.

“How long have you been at Wrykyn, O’Hara?” said Clowes.

O’Hara made a rapid calculation. His fingers twiddled in the air as he worked out the problem.

“Six years,” he said at last, leaning back exhausted with brain work.

“Then you must remember the League?”

“Remember the League? Rather.”

“Well, it’s been revived.”

O’Hara whistled.

“This’ll liven the old place up,” he said. “I’ve often thought of reviving it meself. An’ so has Moriarty. If it’s anything like the Old League, there’s going to be a sort of Donnybrook before it’s done with. I wonder who’s running it this time.”

“We should like to know that. If you find out, you might tell us.”

“I will.”

“And don’t tell anybody else,” said Trevor. “This business has got to be kept quiet. Keep it dark about my study having been ragged.”

“I won’t tell a soul.”

“Not even Moriarty.”

“Oh, hang it, man,” put in Clowes, “you don’t want to kill the poor bhoy, surely? You must let him tell one person.”

“All right,” said Trevor, “you can tell Moriarty. But nobody else, mind.”

O’Hara promised that Moriarty should receive the news exclusively.

“But why did the League go for ye?”

“They happen to be down on me. It doesn’t matter why. They are.”

“I see,” said O’Hara. “Oh,” he added, “about that bat. The search is being ‘vigorously prosecuted’—that’s a newspaper quotation—”

“Times?” inquired Clowes.

“Wrykyn Patriot,” said O’Hara, pulling out a bundle of letters. He inspected each envelope in turn, and from the fifth extracted a newspaper cutting.

“Read that,” he said.

It was from the local paper, and ran as follows:—

“Hooligan Outrage.—A painful sensation has been caused in the town by a deplorable ebullition of local Hooliganism which has resulted in the wanton disfigurement of the splendid statue of Sir Eustace Briggs which stands in the New Recreation Grounds. Our readers will recollect that the statue was erected to commemorate the return of Sir Eustace as member for the borough of Wrykyn, by an overwhelming majority, at the last election. Last Tuesday some youths of the town, passing through the Recreation Grounds early in the morning, noticed that the face and body of the statue were completely covered with leaves and some black substance, which on examination proved to be tar. They speedily lodged information at the police station. Everything seems to point to party spite as the motive for the outrage. In view of the forthcoming election, such an act is highly significant, and will serve sufficiently to indicate the tactics employed by our opponents. The search for the perpetrator (or perpetrators) of the dastardly act is being vigorously prosecuted, and we learn with satisfaction that the police have already several clues.”

“Clues!” said Clowes, handing back the paper, “that means the bat. That gas about ‘our opponents’ is all a blind to put you off your guard. You wait. There’ll be more painful sensations before you’ve finished with this business.”

“They can’t have found the bat, or why did they not say so?” observed O’Hara.

“Guile,” said Clowes, “pure guile. If I were you, I should escape while I could. Try Callao. There’s no extradition there.

‘ On

no petition

Is extradition

Allowed in Callao.’

Either of you chaps coming over to school?”

CHAPTER VIII.

O’Hara on the Track.

UESDAY

mornings at Wrykyn were devoted—up to the quarter to eleven interval—to the

study of mathematics. That is to say, instead of going to their

form-rooms, the various forms visited the out-of-the-way nooks and dens at the

top of the buildings where the mathematical masters were wont to lurk, and

spent a pleasant two hours there playing round games or reading fiction under

the desk. Mathematics being one of the few branches of school learning

which are of any use in after life, nobody ever dreamed of doing any work in

that direction. Least of all O’Hara. It was a theory of O’Hara’s that he

came to school to enjoy himself. To have done any work during a

mathematics lesson would have struck him as a positive waste of time. Especially as he was in Mr. Banks’ class. Mr. Banks was a master who simply

cried out to be ragged. Everything he did and said seemed to invite the

members of his class to amuse themselves. And they amused themselves

accordingly. One of the advantages of being under him was that it was

possible to predict to a nicety the moment when one would be sent out of the

room. This was found very convenient.

UESDAY

mornings at Wrykyn were devoted—up to the quarter to eleven interval—to the

study of mathematics. That is to say, instead of going to their

form-rooms, the various forms visited the out-of-the-way nooks and dens at the

top of the buildings where the mathematical masters were wont to lurk, and

spent a pleasant two hours there playing round games or reading fiction under

the desk. Mathematics being one of the few branches of school learning

which are of any use in after life, nobody ever dreamed of doing any work in

that direction. Least of all O’Hara. It was a theory of O’Hara’s that he

came to school to enjoy himself. To have done any work during a

mathematics lesson would have struck him as a positive waste of time. Especially as he was in Mr. Banks’ class. Mr. Banks was a master who simply

cried out to be ragged. Everything he did and said seemed to invite the

members of his class to amuse themselves. And they amused themselves

accordingly. One of the advantages of being under him was that it was

possible to predict to a nicety the moment when one would be sent out of the

room. This was found very convenient.

O’Hara’s ally, Moriarty, was accustomed to take his mathematics with Mr. Morgan, whose room was directly opposite Mr. Banks’. With Mr. Morgan it was not quite so easy to date one’s expulsion from the room under ordinary circumstances, and in the normal wear and tear of the morning’s work, but there was one particular action which could always be relied upon to produce the desired result. In one corner of the room stood a gigantic globe. The problem—how did it get into the room?—was one that had exercised the minds of many generations of Wrykinians. It was much too big to have come through the door. Some thought that the block had been built round it, others that it had been placed in the room in infancy, and had since grown. To refer the question to Mr. Morgan would, in six cases out of ten, mean instant departure from the room. But to make the event certain, it was necessary to grasp the globe firmly and spin it round on its axis. That always proved successful. Mr. Morgan would dash down from his daïs, address the offender in spirited terms, and give him his marching orders at once and without further trouble.

Moriarty had arranged with O’Hara to set the globe rolling at ten sharp on this particular morning. O’Hara would then so arrange matters with Mr. Banks that they could meet in the passage at that hour, when O’Hara wished to impart to his friend his information concerning the League.

O’Hara promised to be at the trysting-place at the hour mentioned.

He did not think there would be any difficulty about it. The news that the League had been revived meant that there would be trouble in the very near future, and the prospect of trouble was meat and drink to the Irishman in O’Hara. Consequently he felt in particularly good form for mathematics (as he interpreted the word). He thought that he would have no difficulty whatever in keeping Mr. Banks bright and amused. The first step had to be to arouse in him an interest in life, to bring him into a frame of mind which would induce him to look severely rather than leniently on the next offender. This was effected as follows:—

It was Mr. Banks’ practice to set his class sums to work out, and, after some three-quarters of an hour had elapsed, to pass round the form what he called “solutions.” These were large sheets of paper, on which he had worked out each sum in his neat handwriting to a happy ending. When the head of the form, to whom they were passed first, had finished with them, he would make a slight tear in one corner, and, having done so, hand them on to his neighbour. The neighbour, before giving them to his neighbour, would also tear them slightly. In time they would return to their patentee and proprietor, and it was then that things became exciting.

“Who tore these solutions like this?” asked Mr. Banks, in the repressed voice of one who is determined that he will be calm.

No answer. The tattered solutions waved in the air.

He turned to Harringay, the head of the form.

“Harringay, did you tear these solutions like this?”

Indignant negative from Harringay. What he had done had been to make the small tear in the top left-hand corner. If Mr. Banks had asked, “Did you make this small tear in the top left-hand corner of these solutions?” Harringay would have scorned to deny the impeachment. But to claim the credit for the whole work would, he felt, be an act of flat dishonesty, and an injustice to his gifted collaborateurs.

“No, sir,” said Harringay.

“Browne!”

“Yes, sir?”

“Did you tear these solutions in this manner?”

“No, sir.”

And so on through the form.

Then Harringay rose after the manner of the debater who is conscious that he is going to say the popular thing.

“Sir——” he began.

“Sit down, Harringay.”

Harringay gracefully waved aside the absurd command.

“Sir,” he said, “I think I am expressing the general consensus of opinion among my—ahem—fellow-students, when I say that this class sincerely regrets the unfortunate state the solutions have managed to get themselves into.”

“Hear, hear!” from a back bench.

“It is with——”

“Sit down, Harringay.”

“It is with heartfelt——”

“Harringay, if you do not sit down——”

“As your lordship pleases.” This sotto voce.

And Harringay resumed his seat amidst applause. O’Hara got up.

“As me frind who has just sat down was about to observe——”

“Sit down, O’Hara. The whole form will remain after the class.”

“——the unfortunate state the solutions have managed to get thimsilves into is sincerely regretted by this class. Sir, I think I am ixprissing the general consensus of opinion among my fellow-students whin I say that it is with heart-felt sorrow——”

“O’Hara!”

“Yes, sir?”

“Leave the room instantly.”

“Yes, sir.”

From the tower across the gravel came the melodious sound of chimes. The college clock was beginning to strike ten. He had scarcely got into the passage, and closed the door after him, when a roar as of a bereaved spirit rang through the room opposite, followed by a string of words, the only intelligible one being the noun-substantive “globe,” and the next moment the door opened and Moriarty came out. The last stroke of ten was just booming from the clock.

There was a large cupboard in the passage, the top of which made a very comfortable seat. They climbed on to this, and began to talk business.

“An’ what was it ye wanted to tell me?” inquired Moriarty.

O’Hara related what he had learned from Trevor that morning.

“An’ do ye know,” said Moriarty, when he had finished, “I half suspected, when I heard that Mill’s study had been ragged, that it might be the League that had done it. If ye remember, it was what they enjoyed doing, breaking up a man’s happy home. They did it frequently.”

“But I can’t understand them doing it to Trevor at all.”

“They’ll do it to anybody they choose till they’re caught at it.”

“If they are caught, there’ll be a row.”

“We must catch ’em,” said Moriarty. Like O’Hara, he revelled in the prospect of a disturbance. O’Hara and he were going up to Aldershot at the end of the term, to try and bring back the light and middle-weight medals respectively. Moriarty had won the light-weight in the previous year, but, by reason of putting on a stone since the competition, was now no longer eligible for that class. O’Hara had not been up before, but the Wrykyn instructor, a good judge of pugilistic form, was of opinion that he ought to stand an excellent chance. As the prize-fighter in Rodney Stone says, “When you get a good Irishman, you can’t better ’em, but they’re dreadful ’asty.” O’Hara was attending the gymnasium every night, in order to learn to curb his “dreadful ’astiness,” and acquire skill in its place.

“I wonder if Trevor would be any good in a row,” said Moriarty.

“He can’t box,” said O’Hara, “but he’d go on till he was killed entirely. I say, I’m getting rather tired of sitting here, aren’t you? Let’s go to the other end of the passage and have some cricket.”

So, having unearthed a piece of wood from the débris at the top of the cupboard, and rolled a handkerchief into a ball, they adjourned.

Recalling the stirring events of six years back, when the League had first been started, O’Hara remembered that the members of that enterprising society had been wont to hold meetings in a secluded spot, where it was unlikely that they would be disturbed. It seemed to him that the first thing he ought to do, if he wanted to make their nearer acquaintance now, was to find their present rendezvous. They must have one. They would never run the risk involved in holding mass-meetings in one another’s studies. On the last occasion, it had been an old quarry away out on the downs. This had been proved by the not-to-be-shaken testimony of three school house fags, who had wandered out one half-holiday with the unconcealed intention of finding the League’s place of meeting. Unfortunately for them, they had found it. They were going down the path that led to the quarry before-mentioned, when they were unexpectedly seized, blindfolded, and carried off. An impromptu court-martial was held—in whispers—and the three explorers forthwith received the most spirited “touching-up” they had ever experienced. Afterwards they were released, and returned to their house with their zeal for detection quite quenched. The episode had created a good deal of excitement in the school at the time.

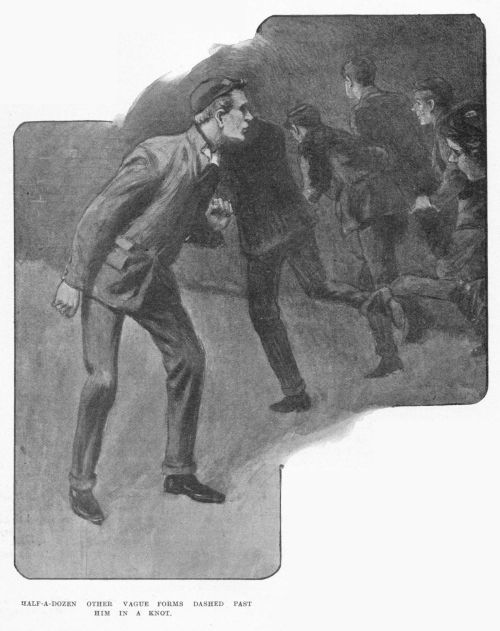

On three successive afternoons O’Hara and Moriarty scoured the downs, and on each occasion they drew blank. On the fourth day, just before lock-up, O’Hara, who had been to tea with Gregson, of Day’s, was going over to the gymnasium to keep a pugilistic appointment with Moriarty, when somebody ran swiftly past him in the direction of the boarding-houses. It was almost dark, for the days were still short, and he did not recognise the runner. But it puzzled him a little to think where he had sprung from. O’Hara was walking quite close to the wall of the College buildings, and the runner had passed between it and him. And he had not heard his footsteps. Then he understood, and his pulse quickened as he felt that he was on the track. Beneath the block was a large sort of cellar-basement. It was used as a store-room for chairs, and was never opened except when prize-day or some similar event occurred, when the chairs were needed. It was supposed to be locked at other times, but never was. The door was just by the spot where he was standing. As he stood there, half-a-dozen other vague forms dashed past him in a knot. One of them almost brushed against him. For a moment he thought of stopping him, but decided not to. He could wait.

On the following afternoon he slipped down into the basement soon after school. It was as black as pitch in the cellar. He took up a position near the door.

It seemed hours before anything happened. He was, indeed, almost giving up the thing as a bad job, when a ray of light cut through the blackness in front of him, and somebody slipped through the door. The next moment, a second form appeared dimly, and then the light was shut off again.

O’Hara could hear them groping their way past him. He waited no longer. It is difficult to tell where sound comes from in the dark. He plunged forward at a venture. His hand, swinging round in a semicircle, met something which felt like a shoulder. He slipped his grasp down to the arm, and clutched it with all the force at his disposal.

(To be continued.)

Note:

The artificial trout in Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat is made of plaster of Paris, not papier-mâché. Wodehouse refers correctly to it as plaster in Psmith in the City (serialized as The New Fold).

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums