The Circle, December 1908

Chapter X

I Enlist the Services of a Minion

HINGS

were not going very well on our model chicken farm. Little accidents marred the

harmony of life in the fowl-run. On one occasion a hen fell into a pot of tar,

and came out an unspeakable object. Chickens kept straying into the wrong

coops, and, in accordance with fowl etiquette, were promptly pecked to death by

the resident. Edwin murdered a couple of Wyandottes, and was only saved from

execution by the tears of Mrs. Ukridge.

HINGS

were not going very well on our model chicken farm. Little accidents marred the

harmony of life in the fowl-run. On one occasion a hen fell into a pot of tar,

and came out an unspeakable object. Chickens kept straying into the wrong

coops, and, in accordance with fowl etiquette, were promptly pecked to death by

the resident. Edwin murdered a couple of Wyandottes, and was only saved from

execution by the tears of Mrs. Ukridge.

In

spite of these occurrences, however, his buoyant optimism never deserted

Ukridge. They were incidents—annoying, but in no way affecting the prosperity

of the farm.

In

spite of these occurrences, however, his buoyant optimism never deserted

Ukridge. They were incidents—annoying, but in no way affecting the prosperity

of the farm.

“After all,” he said, “what’s one bird more or less. Yes, I know I was angry when that beast of a cat lunched off those two, but that was more for the principle of the thing. I’m not going to pay large sums for chickens so that a beastly cat can lunch well. Still, we’ve plenty left, and the eggs are coming in better now, though we’ve a deal of leeway to make up yet in that line. I got a letter from Whiteley’s this morning asking when my first consignment was to arrive. You know, these people make a mistake in hurrying a man. It annoys him. It irritates him. When we really get going, Garney, my boy, I shall drop Whiteley’s. I shall cut them out of my list, and send my eggs to their trade rivals. They shall have a sharp lesson. It’s a little hard. Here am I, worked to death looking after things down here, and these men have the impertinence to bother me about their business!”

It was on the morning after this that I heard him calling me in a voice in which I detected agitation.

“Garnet, come here,” he cried. “I want you to see the most astounding thing.”

I went to the fowl-run where he was standing.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“Blest if I know. Look at those chickens. They’ve been doing that for the last half-hour.”

I inspected the chickens. There was certainly something the matter with them. They were yawning—broadly, as if we bored them. They stood about singly and in groups, opening and shutting their beaks. It was an uncanny spectacle.

“What’s the matter with them?”

“It looks to me,” I said, “as if they were tired of life.”

“Oh, do look at that poor little brown one by the coop,” said Mrs. Ukridge, sympathetically. “I’m sure it’s not well. See, it’s lying down. What can be the matter with it?”

“Can a chicken get a fit of the blues?” I asked. “Because, if so, that’s what they’ve got. I never saw a more bored-looking lot of birds.”

“I tell you what we’ll do,” said Ukridge. “We’ll ask Beale. He once lived with an aunt who kept fowls. He’ll know all about it. Beale!”

No answer.

“Beale!”

A sturdy form in shirt-sleeves appeared through the bushes, carrying a boot. We seemed to have interrupted him in the act of cleaning it.

“Beale, you know about fowls. What’s the matter with these chickens?”

The Hired Retainer examined the blasé birds with a wooden expression on his face.

“Well?” said Ukridge.

“The ’ole thing ’ere,” said the Hired Retainer, “is these ’ere fowls have bin and got the roopUsually spelled roup, it’s the poultry equivalent of influenza: a disease causing inflammation of the head and throat, sneezing, fever, nasal discharge, and the like. Left untreated, it can be fatal..”

I had never heard of the disease before, but it sounded quite horrifying.

“Is that what makes them yawn like that?” said Mrs. Ukridge.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Poor things!”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“And have they all got it?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“What ought we to do?” asked Ukridge.

“Well, my aunt, sir, when ’er fowls ’ad the roop, she give them snuff. Give them snuff, she did,” he repeated, with relish, “every morning.”

“Snuff!” said Mrs. Ukridge.

“Yes, ma’am. She give them snuff till their eyes bubbled.”

Mrs. Ukridge uttered a faint squeak at this vivid piece of word-painting.

“And did it cure them?” asked Ukridge.

“No, sir,” responded the expert, soothingly. “They died.”

“Oh, go away, Beale, and clean your beastly boots,” said Ukridge. “You’re no use. Wait a minute. Who would know about this infernal roop thing? One of those farmer chaps would, I suppose. Beale, go off to Farmer Leigh, at Up Lyme, and give him my compliments, and ask him what he does when his fowls get the roop.”

“Yes, sir.”

“No, I’ll go, Ukridge,” I said. “I want some exercise.”

The path to Up Lyme lies across deep-grassed meadows. At intervals it passes over a stream by means of foot bridges. The stream curls through the meadows like a snake.

And at the first of these bridges I met Phyllis.

I came upon her quite suddenly. The other end of the bridge was hidden from my view. I could hear somebody coming through the grass, but not till I was on the bridge did I see who it was. We reached the bridge simultaneously. She was alone. She carried a sketching-block. I drew back to let her pass.

As it is the privilege of woman to make the first sign of recognition, I said nothing. I merely lifted my hat in a non-committing fashion.

“Mr. Garnet,” she said, stopping at the end of the bridge.

“Miss Derrick?”

“I couldn’t tell you so before, but I am so sorry this has happened.”

“You are very kind,” I said, realizing as I said it the miserable inadequacy of the English language. At a crisis when I would have given a month’s income to have said something epigrammatic, suggestive, yet withal courteous and respectful, I could only find a hackneyed, unenthusiastic phrase which I should have used in accepting an invitation from a bore to lunch with him at his club.

“Of course, you understand my friends must be my father’s friends.”

“Yes,” I said, gloomily; “I suppose so.”

“So you must not think me rude if I—I”——

“Cut me,” said I, with masculine coarseness.

“Don’t seem to see you,” said she, with feminine delicacy, “when I am with my father. You will understand?”

“I shall understand.”

“You see,”—she smiled—”you are under arrest, as Tom says.”

Tom!

“I see,” I said.

“Good-by.”

“Good-by.”

I watched her out of sight, and went on to interview Mr. Leigh.

We had a long and intensely uninteresting conversation about the maladies to which chickens are subject. He was verbose and reminiscent. He took me over his farm, pointing out as we went Dorkings with pasts and Cochin Chinas which he had cured with, as far as I could gather, Christian Science principles.

I left at last with instructions to paint the throats of the stricken birds with turpentine—a task imagination boggled at, and one which I proposed to leave exclusively to Ukridge and the Hired Retainer—and also a slight headache. A visit to the Cob would, I thought, do me good.

It was high tide, and there was deep water on three sides of the Cob.

In a small boat in the offing, Professor Derrick appeared fishing. I had seen him engaged in this pursuit once or twice before. His only companion was a gigantic boatman, by name Harry Hawk.

I sat on the seat at the end of the Cob and watched the professor. It was an instructive sight, an object lesson to those who hold that optimism has died out of the race. I had never seen him catch a fish. He did not look to me as if he were at all likely to catch a fish. Yet he persevered.

There are few things more restful than to watch some one else busy under a warm sun. As I sat there, I began to ponder over the professor. I wondered dreamily if he were very hot; I tried to picture his boyhood; I speculated on his future, and the pleasure he extracted from life.

It was only when I heard him call out to Hawk to be careful, when a movement on the part of that oarsman set the boat rocking, that I began to weave romances round him in which I myself figured.

But, once started, I progressed rapidly. I imagined a sudden upset. Professor struggling in water. Myself (heroically): “Courage! I’m coming!” A few rapid strokes. Saved! Sequel: a subdued professor, dripping salt water and tears of gratitude, urging me to become his son-in-law. That sort of thing happened in fiction; it was a shame that it should not happen in real life. In my hot youth, I once had seven stories in seven weekly penny papers in the same month, all dealing with a situation of the kind. Only the details differed. In other words, I, a very mediocre scribbler, had effected seven times in a single month what the powers of the universe could not manage once, even on the smallest scale.

I was a little annoyed with the powers of the universe.

It was at precisely three minutes to twelve—for I had just consulted my watch—that the great idea surged into my brain. At four minutes to twelve I had been grumbling impotently at Providence; by two minutes to twelve I had determined upon a manly and independent course of action.

Briefly, it was this—since dramatic accident and rescue would not happen of its own accord, I would arrange one for myself. Hawk looked to me the sort of man who would do anything in a friendly way for a few shillings.

That afternoon I interviewed him at the “Net and Mackerel.”

“Hawk,” I said to him, darkly, over a mystic and conspiratorlike pot, “I want you, the next time you take Professor Derrick out fishing”—here I glanced round, to make sure that we were not overheard—“to upset him.”

His astonished face rose slowly from the rim of the pot, like a full moon.

“What ’ud I do that for?” he gasped.

“Five shillings, I hope,” said I; “but I am prepared to go to ten.”

He gurgled.

I argued with the man. I was eloquent, but at the same time concise. My choice of words was superb. I crystallized my ideas into pithy sentences which a child could have understood.

At the end of half an hour he had grasped all the salient points of the scheme. Also he imagined that I wished the professor upset by way of a practical joke.

I let it rest at that. I could not give my true reason, and this served as well as any.

At the last moment he recollected that he, too, would get wet when the accident took place, and raised his price to a sovereign.

A mercenary man. It is painful to see how rapidly the old simple spirit is dying out in rural districts. Twenty years ago a fisherman would have been charmed to do a little job like that for a shilling.

Chapter XI

The Brave Preserver

I COULD have wished, during the next few days, that Mr. Harry Hawk’s attitude toward myself had not been so unctuously confidential and mysterious. It was unnecessary, in my opinion, for him to grin meaningly whenever he met me in the street. His sly wink when we passed each other on the Cob struck me as in indifferent taste. The thing had been definitely arranged (half down and half when it was over), and there was no need for any cloak and dark-lantern effects. I was merely an ordinary, well-meaning man, forced by circumstances into doing the work of Providence. Mr. Hawk’s demeanor seemed to say: “We are two reckless scoundrels, but bless you, I won’t give away your guilty secret.”

The climax came one morning as I was going along the street toward the beach. I was passing a dark doorway, when Mr. Hawk darted out.

“St!” he whispered.

“Now look here, Hawk,” I said, wrathfully, for the start he had given me had made me bite my tongue, “this has got to stop. What is it now?”

“Mr. Derrick goes out this morning, zur.”

“Thank goodness for that,” I said. “Get it over this morning, then, without fail. I couldn’t stand another day of it.”

I went on to the Cob, where I sat down. I was excited. Deeds of great import must shortly be done. I felt a little nervous. It would never do to bungle the thing. Suppose by some accident I were to drown the professor! Or, suppose that, after all, he contented himself with a mere formal expression of thanks, and refused to let bygones be bygones. These things did not bear thinking of.

I got up and began to pace restlessly to and fro.

Presently from the farther end of the harbor there put off Mr. Hawk’s boat, bearing its precious cargo. My mouth became dry with excitement.

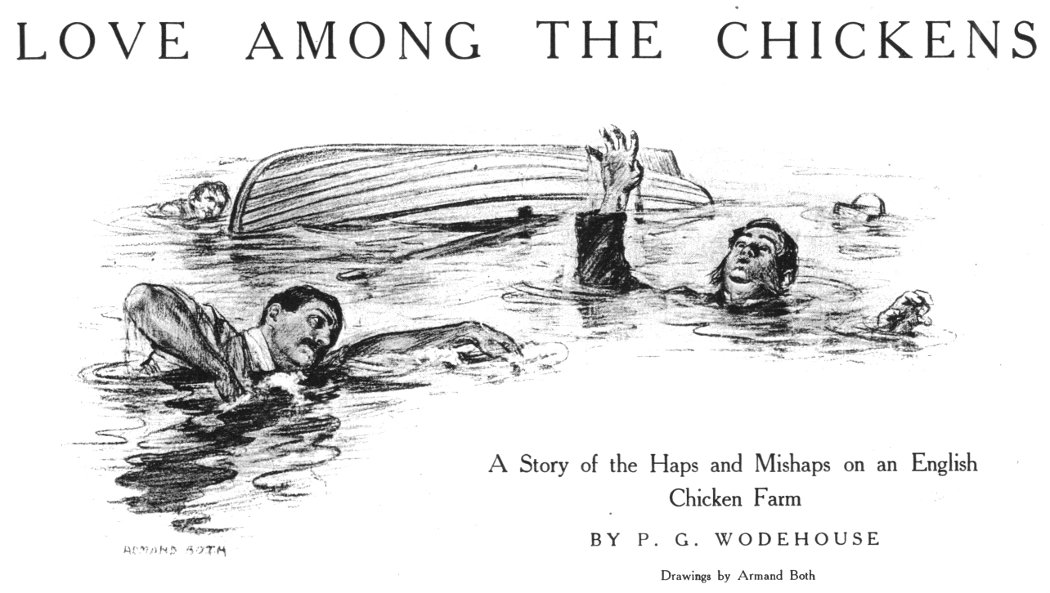

Very slowly Mr. Hawk pulled round the end of the Cob, coming to a standstill some dozen yards from where I was performing my beat. The boat lay almost motionless on the water. I had never seen the sea smoother. It seemed as if this perfect calm might continue forever. Mr. Hawk made no movement. Then suddenly the whole scene changed to one of vast activity. I heard Mr. Hawk utter a hoarse cry, and saw him plunge violently in his seat. The professor turned half round, and I caught sight of his indignant face, pink with emotion. Then the scene changed again with the rapidity of a dissolving viewA scenic effect, either in the theatre or in a miniature viewing cabinet, in which two versions (e.g. day and night views) of a scene painted on a semitransparent screen can be alternately displayed depending on whether the lighting comes from the front or the rear of the screen. I saw Mr. Hawk give another plunge, and the next moment the boat was upside down in the water and I was shooting headforemost to the bottom, oppressed with the indescribably clammy sensation which comes when one’s clothes are thoroughly wet.

I rose to the surface close to the upturned boat. The first sight I saw was the spluttering face of Mr. Hawk. I ignored him, and swam to where the professor’s head bobbed on the waters.

“Keep cool,” I said. A silly remark in the circumstances.

I knew all about saving people from drowning; we used to practise it with a dummy in the swimming-bath at school. I attacked him from the rear, and got a good grip of him by the shoulders. I then swam on my back in the direction of land, and beached him at the feet of an admiring crowd. I had thought of putting him under once or twice just to show him he was being rescued, but decided against such a course as needlessly realistic.

The crowd was enthusiastic.

“Brave young feller,” said somebody.

I blushed. This was Fame.

“Jumped in, he did, sure enough, an’ saved the gentleman!”

The professor stood up, and stretched out his hand.

I grasped it.

“Mr. Garnet,” he said, “we parted recently in anger. Let me

thank you for your gallant conduct, and hope that bygones will be bygones.”

“Mr. Garnet,” he said, “we parted recently in anger. Let me

thank you for your gallant conduct, and hope that bygones will be bygones.”

Like Mr. Samuel WellerMr. Pickwick’s comic manservant in Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers., I liked his conversation much. It was “werry pretty.”

I said: “Professor, the fault was mine. Show that you have forgiven me by coming up to the farm and putting on something dry.”

“An excellent idea, me boy. I am a little wet.”

We walked briskly up the hill to the farm. Ukridge met us at the gate.

“Professor Derrick has had an unfortunate boating accident,” I explained.

“And Mr. Garnet heroically dived, in all his clothes, and saved me life,” broke in the professor. “A hero, sir. A-choo!”

“You’re catching cold, old horse,” said Ukridge, all friendliness and concern, his little differences with the professor having vanished like thawed snow. “This’ll never do. Come upstairs and get into something of Garnet’s. My own toggery wouldn’t fit—what? Come along, come along. Now then, Garny, my boy, out with the duds. What do you think of this, now, professor? A sweetly pretty thing in gray flannel. Here’s a shirt. Socks? Socks forward. Show socks. Here you are. Coat? Try this blazer. That’s right. That’s right.”

He bustled about till the professor was clothed, then marched him downstairs and gave him a cigar.

“Now, what’s all this? What happened?”

“I was fishing, Mr. Ukridge,” the professor explained, “with me back turned, when I felt the boat rock violently from one side to the other, to such an extent that I nearly lost me equilibrium. And then the boat upset. The man’s a fool, sir. I could not see what had happened, my back being turned, as I say.”

“Garnet must have seen. What happened, Marmaduke?”

I tried to smooth things over for Mr. Hawk.

“It was very sudden,” I said. “It seemed to me as if the man had got an attack of cramp. That would account for it. He has the reputation of being a most sober and trustworthy fellow.”

“Never trust that sort of man,” said Ukridge. “They are always the worst. It’s plain to me that this man was beastly drunk, and upset the boat while trying to do a dance.”

We finally got the professor into the best of tempers, and I tried to keep him so. My scheme had been so successful that its iniquity did not worry me. I have noticed that this is usually the case in matters of this kind. It is the bungled crime that brings remorse.

“We must go round the links together one of these days, Mr. Garnet,” said the professor. “I have noticed you there on several occasions, playing a strong game. I have lately taken to using a Schenectady putterA new golf putter with a flat head and the shaft inserted in the centre invented and developed in 1902 by A. F. Knight of Schenectady, which became very popular until it was among a number of centre-shafted, mallet-headed clubs banned by the Royal & Ancient Rules Committee in 1910. [IM]. It is wonderful what a difference it makes. We must certainly arrange a meeting,” concluded the professor. “I have improved my game considerably since I have been down here. Considerably.”

“My only feat worthy of mention since I started the game,” I said, “has been to halve a round with Angus McLurkin at St. Andrews.”

“The McLurkin?” asked the professor, impressed.

“Yes. But it was one of his very off days, I fancy. He must have had gout, or something. And I have certainly never played so well since.”

“Still”——said the professor. “Yes, we must really arrange to meet.”

With Ukridge, who was in one of his less tactless moods, he became very friendly.

Ukridge’s ready agreement with his strictures on the erring Hawk had a great deal to do with this. When a man has a grievance, he feels drawn to those who will hear him patiently and sympathize. Ukridge was all sympathy.

“The man is an unprincipled scoundrel,” he said, “and should be torn limb from limb. Take my advice, Cholmondeley, and don’t go out with him again. Human life isn’t safe with such men as Hawk roaming about.”

“You are perfectly right, sir. The man can have no defense. I shall not employ him again.”

I felt more than a little guilty while listening to this duet on the subject of the man whom I had lured from the straight and narrow pathcf. Matthew 7:14 [IM]. My attempts at excusing him were ill received. Indeed, the professor showed such distinct signs of becoming heated that I abandoned my fellow-conspirator to his fate with extreme promptness. After all, an addition to the stipulated reward—one of these days—would compensate him for any loss which he might sustain from the withdrawal of the professor’s custom.

We saw the professor off the premises in his dried clothes, and I turned back to put the fowls to bed in a happier frame of mind that I had known for a long time. I whistled rag-time airs as I worked.

“Rum old buffer,” said Ukridge, meditatively. “My goodness, I should have liked to have seen him in the water. Why do I miss these good things?”

Chapter XII

Some Emotions and Yellow Lubin

THE fame which came to me through that gallant rescue was a little embarrassing. I was a marked man. Did I walk through the village, heads emerged from windows and eyes followed me out of sight. I was the man of the moment.

“If we’d wanted an advertisement for the farm,” said Ukridge, on one of these occasions, “we couldn’t have had a better one than you, Garny, my boy. You have brought us three distinct orders for eggs during the last week. And I’ll tell you what it is, we need all the orders we can get that’ll bring us in ready money. The farm is in a critical condition, Marmaduke. The coffers are low, deuced low. And I’ll tell you another thing. I’m getting precious tired of living on nothing but chicken and eggs; so’s Milly, though she doesn’t say so.”

“So am I,” I said, “and I don’t feel like imitating your wife’s proud reserve. I never want to see a chicken again.”

For the last week monotony had been the keynote of our commissariat. We had cold chicken and eggs for breakfast, boiled chickens and eggs for lunch, and roast chicken and eggs for dinner. Meals became a nuisance, and Mrs. Beale complained bitterly that we did not give her a chance. She was a cook who would have graced an alderman’s house and served up noble dinners for gourmets, and here she was in this remote corner of the world ringing the changes on boiled chicken and roast chicken and boiled eggs and poached eggs. Mr. WhistlerJames Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), American-born artist active in Britain, one of the most famous painters of his time, set to paint sign-boards for public-houses, might have felt the same restless discontent.

“The fact is,” said Ukridge, “these tradesmen round here seem to be a sordid, suspicious lot. They clamor for money.”

“Can’t you pay some of them a little on account?” I suggested. “It would set them going again.”

“My dear old man,” said Ukridge, impressively, “we need every penny of ready money we can raise for the farm. The place simply eats money. That infernal roop let us in for I don’t know what.”

That insidious epidemic had indeed proved costly. We had painted the throats of the chickens with the best turpentine—at least Ukridge and Beale had—but in spite of their efforts dozens had died, and we had been obliged to sink much more money than was pleasant in restocking the run.

“No,” said Ukridge, summing up, “these men must wait. We can’t help their troubles. Why, good gracious, it isn’t as if they’d been waiting for the money long. We’ve not been down here much over a month. I never heard of such a scandalous thing. ’Pon my word, I’ve a good mind to go round and have a straight talk with one or two of them. I come and settle down here, and stimulate trade, and give them large orders, and they worry me with bills when they know I’m up to my eyes in work, looking after the fowls. One can’t attend to everything. This business is just now at its most crucial point. It would be fatal to pay any attention to anything else with things as they are. These scoundrels will get paid all in good time.”

It is a peculiarity of situations of this kind that the ideas of debtor and creditor as to what constitutes good time never coincide.

I am afraid that, despite the urgent need for strict attention to business, I was inclined to neglect my duties about this time. I had got into the habit of wandering off, either to the links, where I generally found the professor, and sometimes Phyllis, or on long walks by myself.

I had not been inside the professor’s grounds since the occasion when I had gone in through the boxwood hedge. But on the afternoon following my financial conversation with Ukridge I made my way thither, after a toiletin this context, meaning the process of getting dressed; the use of this word as a euphemism for restroom or water closet was a fairly recent American coinage at the time which from its length should have produced better results than it did.

Not for four whole days had I caught so much as a glimpse of Phyllis. I had been to the links three times, and had met the professor twice, but on both occasions she had been absent. I had not had the courage to ask after her. I had an absurd idea that my voice or my manner would betray me in some way.

The professor was not at home; nor was Mr. Chase; nor was Miss Norah Derrick, the lady I had met on the beach with the professor. Miss Phyllis, said the maid, was in the garden.

I went into the garden. She was sitting under the cedar by the tennis-lawn, reading. She looked up as I approached.

To

walk any distance under observation is one of the most trying things I know. I

advanced in bad order, hoping that my hands did not really look as big as they

felt. The same remark applied to my feet. In emergencies of this kind a

diffident man could very well dispense with extremities. I should have liked to

have been wheeled up in a bath-chairwheelchair, esp. of the hooded kind used by invalids visiting the spas at Bath, England; not ‘a chair for bathing in’! .

.

I said it was a lovely afternoon. After which there was a lull in the conversation. I was filled with a horrid fear that I was boring her.

“I—er—called in the hope of seeing Professor Derrick,” I said.

“You would find him on the links,” she replied. It seemed to me that she spoke wistfully.

“Oh, it—it doesn’t matter,” I said. “It wasn’t anything important.”

This was true. If the professor had appeared then and there, I should have found it difficult to think of anything to say to him which would have accounted for my anxiety to see him.

We paused again.

“How are the chickens, Mr. Garnet?” said she.

The situation was saved. Conversationally, I am like a clockwork toy. I have to be set going. On the affairs of the farm I could speak fluently. I sketched for her the progress we had made since her visit. I was humorous concerning roop, epigrammatic on the subject of the Hired Retainer and Edwin.

“Then the cat did come down from the chimney?” said Phyllis.

We both laughed, and—I can answer for myself—felt the better for it.

“He came down next day,” I said, “and made an excellent lunch off one of our best fowls. He also killed another, and only just escaped death himself at the hands of Ukridge.”

“And have you had any success with the incubator? I love incubators. I have always wanted to have one of my own, but we have never kept fowls.”

“The incubator has not done all that it should have done,” I said. “Ukridge looks after it, and I fancy his methods are not the right methods. I don’t know if I have got the figures absolutely correct, but Ukridge reasons on these lines. He says you are supposed to keep the temperature up to a hundred and five degreesCurrent incubator instructions suggest temperatures close to 101 degrees F, hatching in 21 days.. I think he said a hundred and five. Then the eggs are supposed to hatch out in a week or so. He argues that you may just as well keep the temperature at seventy-two, and wait a fortnight for your chickens. I am certain there’s a fallacy in the system somewhere, because we never seem to get as far as the chickens. But Ukridge says his theory is mathematically sound, and he sticks to it.”

“Are you quite sure that the way you are doing it is the best way to manage a chicken-farm?”

“I should very much doubt it. I am a child in these matters. I had only seen a chicken in its wild state once or twice before we came down here. I had never dreamed of being an active assistant on a real farm. Ukridge called at my rooms one beautiful morning when I was feeling desperately tired of London and overworked and dying for a holiday, and suggested that I should come to Lyme Regis with him and help him farm chickens. I have not regretted it.”

“It is a lovely place, isn’t it?”

“The loveliest I have ever seen. How charming your garden is.”

“Shall we go and look at it? You have not seen the whole of it.”

As she rose, I saw her book, which she had laid face downward on the grass beside her. It was that same much-enduring copy of the “Maneuvers of Arthur.”Jeremy Garnet’s novel; see Chapter III in the first installment, where it is spelled ‘Manoeuvers’

As we wandered down the gravel paths, she gave me her opinion of the book. In the main it was appreciative.

“Of course, I don’t know anything about writing books,” she said.

“Yes?” My tone implied, or I hoped it did, that she was an expert on books, and that if she were not it didn’t matter.

“But I don’t think you do your heroines well. I have got ‘The Outsider’ ”——

(My other novel. Bastable & Kirby, 6s. Satirical. All about Society—of which I know less than I know about chicken-farming. Slated by Times and Spectator. Well received by the Pelican.)

—“and,” continued Phyllis, “Lady Maud is exactly the same as Pamela in the ‘Maneuvers of Arthur.’ I thought you must have drawn both characters from some one you knew.”

“No,” I said. “No.”

“I am so glad,” said Phyllis.

And then neither of us seemed to have anything to say.

My knees began to

tremble. I realized that the moment had arrived when my fate must be put to

the touchHe either fears his fate too much

Or his deserts are small

That puts it not unto the touch

To win or lose it all.

—from “My Dear and Only Love” by James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1612–1650), and I feared that the moment was premature. We can not arrange these

things to suit ourselves. I knew that the time was not yet ripe; but the magic

scent of the yellow lubinmore commonly spelled ‘lupine’ was too much for me.

“Miss Derrick,” I said, hoarsely.

Phyllis was looking with more intentness than the attractions of the flower justified at a rose she held in her hand. The bees hummed in the lubin.

“Miss Derrick,” I said, and stopped again.

“I say, you people,” said a cheerful voice, “tea is ready. Hullo, Garnet, how are you? That medal arrived yet from the Humane Society?”

I spun round. Mr. Tom Chase was standing at the end of the path. The only word that could deal adequately with the situation slapped against my front teeth. I grinned a sickly grin.

“Well, Tom,” said Phyllis.

And there was, I thought, just the faintest trace of annoyance in her voice. We went in to tea.

“Met the professor’s late boatman on the Cob,” said Mr. Chase, dissecting a chocolate cake.

“Clumsy man,” said Phyllis; “I hope he was ashamed of himself. I shall never forgive him for trying to drown papa.”

My heart bled for Mr. Henry Hawk, that modern martyr.

“When I met him,” said Tom Chase, “he looked as if he had been trying to drown his sorrow as well.”

“I knew he drank,” said Phyllis, severely, “the very first time I saw him.”

“You might have warned the professor,” murmured Mr. Chase.

“He couldn’t have upset the boat if he had been sober.”

“You never know. He may have done it on purpose.”

“How absurd.”

“Rather rough on the man, aren’t you?” I said.

“Merely a suggestion,” continued Mr. Chase, airily. “I’ve been reading sensational novels lately, and it seems to me that Hawk’s cut out to be a minion. Probably some secret foe of the professor’s bribed him.”

My heart stood still. Did he know, I wondered, and was this all a roundabout way of telling me that he knew?

“The professor may be a member of an Anarchist League, or something, and this is his punishment for refusing to assassinate the Kaiser.”

“Have another cup of tea, Tom, and stop talking nonsense.”

Mr. Chase handed over his cup.

“What gave me the idea that the upset was done on purpose was this. I saw the whole thing from the Ware cliff.”

“That man Hawk ought to be prosecuted,” said Phyllis, blazing with indignation.

“But why on earth,” I asked, as calmly as possible, “should he play a trick like that on Professor Derrick, Chase?”

“Pure animal spirits, probably. Or he may, as I say, be a minion.”

I felt like a criminal in the dock when the case is going against him.

“I shall tell father that,” said Phyllis, in her most decided voice, “and see what he says. I don’t wonder at the man taking to drink after doing such a thing.”

“I—I think you’re making a mistake,” I said.

“I never make mistakes,” Mr. Chase replied. “I am called Archibald the All-Right, for I am Infallible.A direct quotation from Patience, in which W. S. Gilbert gives this line to Archibald Grosvenor, an idyllic poet in that satire of aestheticism I propose to keep a reflective eye upon the jovial Hawk.”

He helped himself to another section of the chocolate cake.

“Haven’t you finished yet, Tom?” inquired Phyllis. “I’m sure Mr. Garnet’s getting tired of sitting here.”

I shot out a polite negative. Mr. Chase explained with his mouth full that he had by no means finished. Chocolate cake, it appeared, was the dream of his life. I suddenly decided to go home. I did not feel that my secret was safe so long as I sat at the table with any one so detestably suspicious as this man Chase.

(To be continued)

Editor’s notes:

roop: Usually spelled roup, it’s the poultry equivalent of influenza: a disease causing inflammation of the head and throat, sneezing, fever, nasal discharge, and the like. Left untreated, it can be fatal.

dissolving view: A scenic effect, either in the theatre or in a miniature viewing cabinet, in which two versions (e.g. day and night views) of a scene painted on a semitransparent screen can be alternately displayed depending on whether the lighting comes from the front or the rear of the screen

Mr. Samuel Weller: Mr. Pickwick’s comic manservant in Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers

Schenectady putter: A new golf putter with a flat head and the shaft inserted in the centre invented and developed in 1902 by A. F. Knight of Schenectady, which became very popular until it was among a number of centre-shafted, mallet-headed clubs banned by the Royal & Ancient Rules Committee in 1910. [IM]

the straight and narrow path: cf. Matthew 7:14 [IM]

Mr. Whistler: James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), American-born artist active in Britain, one of the most famous painters of his time

toilet: in this context, meaning the process of getting dressed; the use of this word as a euphemism for restroom or water closet was a fairly recent American coinage at the time

bath-chair: wheelchair, esp. of the hooded kind used by invalids visiting the spas at Bath, England; not ‘a chair for bathing in’!

a hundred and five degrees: Current incubator instructions suggest temperatures close to 101 degrees F, hatching in 21 days.

that same much-enduring copy of the “Maneuvers of Arthur”: Jeremy Garnet’s novel; see Chapter III in the first installment, where it is spelled ‘Manoeuvers’

my fate must be put to the touch:

He either fears his fate too much

Or his deserts are small

That puts it not unto the touch

To win or lose it all.

—from “My Dear and Only Love” by James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1612–1650)

lubin: more commonly spelled ‘lupine’

“I am called Archibald the All-Right, for I am

Infallible”: A direct quotation from Patience, in which W. S. Gilbert gives this line to Archibald Grosvenor, an idyllic poet in that satire of aestheticism

—Notes by Neil Midkiff, with contributions from Ian Michaud

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums