Collier’s Weekly, August 26, 1911

I WANT to tell you all about dear old Bobbie Cardew. It’s a most interesting story. I can’t put in any literary style and all that; but I don’t have to, don’t you know, because it goes on its moral lesson. If you’re a man, you mustn’t miss it, because it’ll be a warning to you; and if you’re a woman, you won’t want to, because it’s all about how a girl made a man feel like thirty cents.

Maybe you’re a recent acquaintance of Bobbie’s? If so, you’ll probably be surprised to hear that there was a time when he was more remarkable for the weakness of his memory than anything else. Dozens of fellows, who have only met Bobbie since the change took place, have been surprised when I told them that. Yet it’s true. Believe me.

In the days when I first knew him, Bobbie Cardew was about the most pronounced young bonehead between the Battery and Harlem. People have called me a silly ass, but I was never in the same class with Bobbie. He was a champion, and I was just jogging along in the preliminaries. Why, if I wanted him to dine with me, I used to mail him a letter at the beginning of the week, and then the day before send him a telegram and a phone call on the day itself, and—half an hour before the time we’d fixed—a messenger in a taxi, whose business it was to see that he got in and that the chauffeur had the address all correct. By doing that I generally managed to get him, unless he had left town before my messenger arrived.

THE funny thing was that he wasn’t altogether a fool in other ways. Deep down in him there was a kind of stratum of sense. I had known him, once or twice, show an almost human intelligence. But to reach that stratum, mind you, you needed dynamite.

At least, that’s what I thought. But there was another way which hadn’t occurred to me. Marriage, I mean. Marriage, the dynamite of the soul; that was what hit Bobbie. He married. Have you ever seen a bull-pup chasing a bee? The pup sees the bee. It looks good to him. But he doesn’t know what’s at the end of it till he gets there. It was like that with Bobbie. He fell in love, got married—with a sort of whoop, as if it were the greatest fun in the world—and then began to find out things.

She wasn’t the sort of girl you would have expected Bobbie to get up in the air about. And yet I don’t know. What I mean is, she worked for her living; and to a fellow who has never done a hand’s turn in his life there’s undoubtedly a sort of fascination, a kind of romance, about a girl who works for her living. I was in love myself once with a girl called Kathryn Mae Shubrick, who worked for a firm on Fifth Avenue: and the story of how she turned me down for a bill-clerk will be recorded in my biography, if I ever write it.

Bobbie’s girl’s name was Anthony. Mary Anthony. She was about five feet six; she had a ton and a half of red-gold hair, gray eyes, and one of those determined chins. She worked in Bobbie’s lawyer’s office. That’s where Bobbie met her. I don’t know what her particular job was, but I bet she was good at it. She had character.

BOBBIE broke the news to me at the club one evening, and next day he introduced me to her. I admired her. I’ve never worked myself—my name’s Pepper, by the way. Almost forgot to mention it. Reggie Pepper. My uncle Edward was Pepper’s Safety-Razor. He left me a sizable wad—I say I’ve never worked myself, but I admire any one who earns a living under difficulties, especially a girl. And this girl had had a rather unusually tough time of it.

Bobbie told me about her. Her father had had money at one time, I believe, but he’d lost it all somehow; and, being too proud to work, he just filled in his time drinking. He had a habit of coming to offices where Mary had a job, and weeping on the boss’s shoulder—which had lost Mary more than one place. Also, I gathered, he got away with most of her weekly envelope. Take him for all in all, he was something of a nut.

Mary and I got along together fine. We don’t now, but we’ll come to that later. I’m speaking of the past. She seemed to think Bobbie the greatest thing on earth, judging by the way she looked at him when she thought I wasn’t noticing. And Bobbie was crazy about her. So that I came to the conclusion that, if only dear old Bobbie didn’t forget to go to the wedding, they had a sporting chance of being quite happy.

Well, let’s speed up a bit here, and jump a year. The story doesn’t really start till then. All I’ve told you up to now is only like dealing the deck. We now sit in at the game.

They took an apartment at the Gargantua, and settled down. I was in and out of the place quite a good deal. I kept my eyes open, and everything seemed to me to be running along as solid as you please. Sioux Falls out of sight over the horizon, and Reno not on the map at all. If this was marriage, I thought, I couldn’t see why fellows were so scared of it. There was a heap of worse things that could happen to a man.

But we now come to the incident of the Quiet Dinner, and it’s just here that love’s young dream gets a jolt, and things begin to happen.

It was one of those come-right-along dinners. You know. You get talking with a man at the club or somewhere, and, when you’re through, he says: “Come right along and have a bit of dinner. My wife’ll be tickled to death to see you.” It sounds good, but it’s incomplete. It wants the word not slipped into it. Generally I side-step like a shying horse; but, seeing that I was so much the old family friend in that particular household, I thought I should be safe in breaking my rule for once; so, like a fool, I went along.

WHEN we got to the Gargantua, there was Mrs. Bobbie looking—well, I tell you it staggered me. Her golden hair was all piled up in waves and crinkles and things, with a what-d’you-call-it of diamonds in it. And she was wearing the most perfectly corking dress. I couldn’t begin to describe it. I can only say it was the limit. It struck me that if this was how she was in the habit of looking every night when they were dining quietly at home together it was no wonder that Bobbie liked domesticity.

“Here’s old Reggie, dear,”

said Bobbie. “I’ve brought him home to have a

bit of dinner. I’ll phone down to the kitchen and have them send

it up right away.”

“Here’s old Reggie, dear,”

said Bobbie. “I’ve brought him home to have a

bit of dinner. I’ll phone down to the kitchen and have them send

it up right away.”

She stared at him as if she had never seen him before. Then she turned scarlet. Then she turned as white as a sheet. Then she gave a little laugh. It was most interesting to watch. Made me wish I was up a tree about eight hundred miles away. Then she recovered herself.

“I am so glad you were able to come, Mr. Pepper,” she said, smiling at me.

AND after that she was all right. At least, you would have said so. She talked a lot at dinner, and chaffed Bobbie, and played us rag-time on the piano afterward, as if she hadn’t a care in the world. Quite a jolly little party it was—not. I’m no lynx-eyed sleuth, and all that sort of thing, but I had seen her face at the beginning, and I knew that she was working the whole time, and working hard to keep herself in hand, and that she would have given that diamond what’s-its-name in her hair and everything else she possessed to have one good scream—just one. I’ve sat through some pretty tough evenings in my time, but that one had the rest lashed to the mast. At the very earliest moment I grabbed my hat and made my getaway.

Having seen what I did, I wasn’t particularly surprised to meet Bobbie at the club next day looking about as merry and bright as a chicken at a camp-meeting.

He started in right away. He seemed glad to have some one to talk to about it.

“Do you know how long I’ve been married?” he said.

I didn’t exactly.

“About a year, isn’t it?”

“Not about a year,” he said sadly. “About nothing. Exactly a year—yesterday!”

Then I got him. I saw light—a regular flash of light.

“Yesterday was—?”

“The anniversary of the wedding. I’d arranged to take Mary to Sherry’s, and on to the opera. She particularly wanted to hear Caruso. I had the ticket for the box in my pocket. Say, all through dinner I had a kind of idea that there was something I’d forgotten, but I couldn’t fix it.”

“Till your wife mentioned it?”

He nodded.

“She—mentioned it,” he said thoughtfully.

I didn’t ask for details. Women with hair and chins like Mary’s may be angels most of the time, but, when they take off their wings for a spell, they are no pikers—they go the limit.

“To be absolutely frank, old scout,” said poor old Bobbie in a broken sort of way, “I’m in rather bad at home.”

There didn’t seem much to be done. I just lit a cigarette, and sat there. He didn’t want to talk. Presently he went out. I stood at the window of our upper smoking-room, which looks out on to the Avenue, and watched him. He walked slowly along for a few yards, stopped, then walked on again and finally turned into Tiffany’s—which was an instance of what I meant when I said that deep down in him there was a certain stratum of sense.

IT WAS from now on that I began to be really interested in this thing of Bobbie’s married life. Of course, one’s always mildly interested in one’s friends’ marriages, hoping they’ll turn out well, and all that; but this was different. The average man isn’t like Bobbie, and the average girl isn’t like Mary. It was that old stunt of the immovable mass and the irresistible force. There was Bobbie, ambling gently through life, a dear old chap in a hundred ways, but undoubtedly a star performer in the chump class.

And there was Mary, determined that he shouldn’t be a chump. And Nature, mind you, on Bobbie’s side. When Nature makes a chump like dear old Bobbie, she’s proud of him, and doesn’t want her handiwork disturbed. She gives him a sort of natural armor to protect him against outside interference. And that armor is shortness of memory. Shortness of memory keeps a man a chump, when, but for it, he might cease to be one. Take my case, for instance. I’m a chump. Well, if I had remembered half the things people have tried to teach me during my life, I should be a high-brow of the first water. But I didn’t. I forgot them. And it was just the same with Bobbie.

For about a week, maybe a bit more, the recollection of that quiet little domestic evening kept him up on his toes. Elephants, I read somewhere, are champions at the memory thing, but they hadn’t anything on Bobbie during that week. But, bless you, the shock wasn’t nearly big enough. It had dented the armor, but it hadn’t made a hole in it. Pretty soon he was back at the old stunts.

It was pathetic, don’t you know. The poor girl loved him, and she was scared. It was the thin end of the wedge, you see, and she knew it. A man who forgets what day he was married, when he’s been married one year, will forget, at about the end of the fourth, that he’s married at all. If she meant to get him in hand ever, it was up to her to do it now, before he began to drift away.

I saw that clear enough, and I tried to make Bobbie see it, when he was by way of putting up a hard-luck story to me one afternoon. I can’t remember what it was that he had forgotten the day before, but it was something she had asked him to bring home for her—it may have been a book.

“It’s such a dinky thing to make a fuss about,” said Bobbie. “And she knows that it’s simply because I’ve got such an infernal memory about everything. I can’t remember anything. Never could.”

He talked on for a while, and, just as he was going, he pulled out a ten-spot.

“Oh, by the way,” he said.

“What’s this for?” I asked, though I knew.

“I owe it you!”

“How’s that?” I said.

“Why, that bet on Tuesday. In the billiard-room. Murray and Brown were playing a hundred up, and I gave you ten bucks to five that Brown would win, and Murray beat him by twenty-odd.”

“So you do remember some things?” I said.

He got quite warm beneath the collar. Said that if I thought he was the sort of cheap skate who forgot to pay when he lost a bet, I’d got another guess coming, and pulled a lot more stuff like that. I told him to cut it out, and gave him a cocktail. Then I spoke to him like a father.

“You want to pull yourself together, old scout,” I said. “As things are shaping, you’re due to get yours before you know what’s hit you. You want to make an effort. Don’t say you can’t. This business of the ten-spot shows that, even if your memory is rocky, you can remember some things. It’s up to you to see that wedding anniversaries and so on are included in the bunch. It may be a brain-strain, but you can’t side-step it.”

“I guess you’re right,” said Bobbie. “But it beats me why she thinks such a heap of these dinky little dates. What’s it matter if I forget what day we were married on or what day she was born on or what day the janitor’s cat had the measles? She knows I love her just as much as if I were a memorizing freak in vaudeville.”

“Women come from Missouri,” I said, “—all of them; and they want to be shown. Bear that in mind, and you win out. Forget it, and you’re up against it.”

He chewed the knob of his stick.

“Women are darned queer,” he said gloomily.

“You should have thought of that before you married one,” I said.

Then I gave him another cocktail, and left him to think it over.

I DON’T see that I could have done any more. I had put the whole thing in a nutshell for him. You would have thought he’d have seen the point, and that it would have made him brace up and take a hold on himself. But no. Off he went again in the same old way. I gave up arguing with him. I had a good deal of time on my hands, but not enough to amount to anything when it was a question of reforming dear old Bobbie by argument. If you see a man asking for trouble, and insisting on getting it, the only thing to do is to stand by and wait till it comes to him. After that you may get a chance. But till then there’s nothing doing. But I thought a heap about him.

TROUBLE didn’t hit Bobbie all at once. Weeks went by, and months, and still it was a case of all quiet along the Potomac. Now and then he’d blow into the club with a kind of cloud on his shining morning face, and I’d know that there had been something doing in the home; but it wasn’t till ’way on in the spring that he got the thunderbolt just where he had been asking for it—in the thorax.

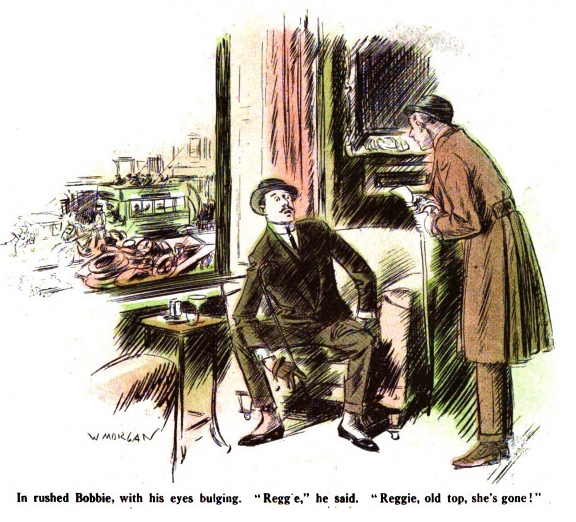

I was smoking a quiet cigarette one morning in the

window looking out over the Avenue, and watching the

carriages and motors going up one way and down the other—most

interesting it is. I often do it—when in rushed Bobbie,

with his eyes bulging and his face the color of an oyster, waving

a piece of paper in his hand.

I was smoking a quiet cigarette one morning in the

window looking out over the Avenue, and watching the

carriages and motors going up one way and down the other—most

interesting it is. I often do it—when in rushed Bobbie,

with his eyes bulging and his face the color of an oyster, waving

a piece of paper in his hand.

“Reggie,” he said. “Reggie, old top, she’s gone!”

“Gone!” I said. “Who?”

“Mary, of course. Gone! Quit me! Gone!”

“Where?” I said.

Foolish question? Maybe. Anyway, dear old Bobbie nearly foamed at the mouth.

“Where? How should I know where? Here, read this.”

He pushed the paper into my hand. It was a letter.

“Go on,” said Bobbie. “Read it.”

SO I DID. It certainly was some letter. There was not much of it, but it was all to the point.

This is what it said:

“My dear Bobbie. I am going away. When you care enough about me to remember to wish me many happy returns on my birthday, I will come back. My address will be Box 341, New York ‘Morning News.’ ”

I read it twice, then I said: “Well, why don’t you?”

“Why don’t I what?”

“Why don’t you wish her many happy returns? It doesn’t seem much to ask.”

“But she says on her birthday.”

“Well, when is her birthday?”

“Can’t you understand?” said Bobbie. “I’ve forgotten, you lunkhead.”

“Forgotten!” I said.

“Yes,” said Bobbie. “Forgotten.”

“How do you mean forgotten?” I said. “Forgotten whether it’s the twentieth or the twenty-first, or what? How near do you get to it?”

“I know it came somewhere between the first of January and the thirty-first of December. That’s how near I get to it.”

“Think.”

“Think? What’s the use of saying ‘Think’? Think I haven’t thought? I’ve been knocking sparks out of my brain ever since I opened that letter.”

“And you can’t remember.”

“No.”

I rang the bell and ordered restoratives.

“Well, Bobbie,” I said, “it’s a pretty tough proposition to spring on an untrained amateur like me. I guess old Doctor Holmes himself would have sidestepped it. Suppose some one had come to him and said: ‘Mr. Holmes, here’s a case for you. When is my wife’s birthday?’ wouldn’t that have jarred Sherlock? However, I know enough about the game to understand that a sleuth can’t unlimber his deductive theories unless you start him off with a clue, so rouse yourself out of that pop-eyed trance and come across with two or three. For instance, can’t you remember the last time she had a birthday? What sort of weather was it? That might fix the month.”

BOBBIE shook his head.

“It was just ordinary weather, as near as I can recollect.”

“Warm?”

“Warmish.”

“Or cold?”

“Well, half-way cold, perhaps. I can’t remember.”

I ordered two more of the same. They seemed indicated in the Young Detective’s Manual.

“You’re a great help, Bobbie,” I said. “An invaluable assistant. One of those indispensable adjuncts without which no home is complete.”

Bobbie worked steadily down to the cherry without answering. He seemed to be thinking.

“I’ve got it,” he said suddenly. “See here. I gave her a present on her last birthday. All we have to do is to go to the store, hunt up the date when it was bought, and the thing’s done.”

“Sure. What did you give her?”

He sagged.

“I can’t remember,” he said.

Getting ideas is like golf. Some days you’re right off it, on others it’s as easy as falling off a log. I don’t suppose dear old Bobbie had ever had two ideas on the same morning before in his life; but now he did it without an effort. He just loosed another dry Martini into the undergrowth, and before you could turn round it had scared up the best brainwave of the session.

“I have it,” he said. “Why didn’t I think of it before? Come along and find Mary’s father. He’ll put us next.”

OLD man Anthony, that prominent alcohol specialist, lived way out on Staten Island. He had been something of a problem to Bobbie for a while after the marriage, owing to his habit of blowing into the club in search of son-in-law and shedding tears of pure rye in the vestibule. The club authorities had tipped Bobbie off to close down the entertainment, and after that the dead-line for father, except when he paid state visits to the apartment, was Fourteenth Street. It was Bobbie who had suggested Staten Island. He held the purse, and what he said went.

The exile was charmed to see us, and made an automatic movement toward the ice-chest, but Bobbie stopped him, and explained that we were not there for social revelry, but strictly on business. When was Mary’s birthday? That was the burning question of the day.

“Mary’s birthday?” he said. “Why, September 10, of course. Where’s your memory? I know it was September 10 because I remember saying to my poor dear wife, now in heaven, how strange that it should be September 10.”

“Why strange?” I asked.

“Why, it was the anniversary of something. I can’t for the moment recollect what, but something.”

“You’re sure of it?” said Bobbie.

“Certain,” said dad. “You’ll have one now, won’t you?” We said we would. Poor old Bobbie, he was as pleased as if he’d found a million in his Christmas stocking. It was quite touching to see him doing the grateful son-in-law act. The old man had two twenties off him in the first minute, and he smiled through it all.

Just as we were going a thoughtful look came into father’s face.

“Wait,” he said.

“What’s the matter now?” said Bobbie.

“I was wrong,” said father.

“Wrong?”

“Yes. It wasn’t September 10. It all comes back to me now. I can’t think what put it into my head. Mary wasn’t born on September 10.”

“When was she born, then?”

“Ah!” said dad, scorning to deceive, “there you have me, my boy.”

Nobody could say the old man wasn’t obliging. He did his best. He dug up April 4. For about ten minutes he went solid for April 4. Then he weakened. It might be April 4, or it might not. He rather fancied it was July 4. In another quarter of an hour he had given up July 11 and was rooting hard for January 8. And he had good reasons for all of them, mind you. They were all anniversaries of something which had slipped his memory for the moment, and he had said as much at the time to his poor, dear wife, now in heaven. Alcohol may be a food, as the wise guys tell you, but you can take it from me it’s not a brain food. I led Bobbie off after a while in what you might call an overwrought condition, and we moved back in bad order to old Manhattan.

There was no yellow streak in Bobbie. He was no quitter. Up he came next day with another idea. And this time it was a corker.

Do you know those little books called “When were you born?” There’s one for each month. They tell you your character, your talents, your strong points, and your weak points at five cents a throw. Bobbie had bought the whole twelve, and he was red-hot on the trail.

“See here,” he said, “we’ll go through these and find out which month hits old Mary’s character. That’ll give us the month and narrow it down a whole heap.”

IT sounded good, I admit. But when we came to go into the thing we saw that there was a flaw. There was plenty of information all right, but there wasn’t a single month that didn’t have something that exactly hit off Mary. For instance, in the December book it said: “December people are apt to keep their own secrets. They are extensive travelers.” Well, Mary had certainly kept her secret and she had traveled quite extensively enough for Bobbie’s needs. Then, October people were “born with original ideas” and “loved moving.” You couldn’t have summed up Mary’s little jaunt more neatly. February people had “wonderful memories”—Mary’s specialty.

Bobbie was strong for May because the book said that women born in that month were “inclined to be capricious, which is always a barrier to a happy married life”; but I raised him with August, because August women were “apt to blunder in their first marriage, but usually do not hesitate to get a divorce.” He didn’t like that a little bit, but he owned that it seemed to him more than apt to be Mary.

After a while he tore the books up one by one, burnt them, and went home.

It was wonderful what a change the next few days made in dear old Bobbie. Have you ever seen that picture, “The Soul’s Awakening”? It represents a blonde well up in the peacherino class rubbering in a startled sort of way into the middle distance with a look in her eyes that seems to say: “Surely, that is George’s step I hear on the porch. Can this be love?” Well, Bobbie had a soul’s awakening too. I don’t suppose he had ever troubled to think in his life before—not really think. But now he was wearing his brain to the bone. He was saying the sort of things to himself that the football coach says to the squad when they’re eight points down at the end of the second quarter. It was painful in a way, of course, to see a fellow human being so thoroughly up against it, but I felt strongly that it was all for the best. I could see as plainly as possible that all these brain-storms were improving Bobbie out of knowledge. When it was all over he might possibly become a chump of a sort again, but it would only be a pale reflection of the chump he had been. It bore out the idea I had always had that what he needed was a real good jolt.

I saw a great deal of him these days. I was his best friend, and he came to me for sympathy. I gave it to him too, with both hands, but I never failed to slip over the Moral Lesson when I had him weak.

ONE day he came to me as I was sitting in the club, and I could see that he had had an idea. He looked happier than he had for weeks.

“Reggie,” he said, “I’m on the trail. This time I’m convinced that I shall win out. I’ve remembered something of vital importance.”

“Yes?” I said.

“I remember distinctly,” he said, “that on Mary’s last birthday we went together to see the show at Weinstein’s. How does that hit you?”

“It’s a fine bit of memorizing,” I said, “but how does it help?”

“Why, they change the program every week there.”

“Ah!” I said. “Now you are showing a flash of speed.”

“And the week we went one of the turns was Professor Someone’s Terpsichorean Cats. I recollect them distinctly because Mary said it was a shame making cats do those stunts. Now, are we narrowing it down or aren’t we? Say, I’m going around to Weinstein’s this minute, and I’m going to dig the date of those Terpsichorean Cats out of them if I have to use a crowbar.”

So that got him within six days, for the management treated us like brothers, brought out the archives, and ran fat fingers over the pages till they treed the cats in the middle of May.

“I told you it was May,” said Bobbie: “maybe you’ll listen to me another time.”

“If you’ve any sense,” I said, “there won’t be another time.”

And Bobbie allowed that there wouldn’t.

Once you get your memory on the run it loosens up as if it enjoyed doing it. I had just got off to sleep that night when my telephone bell rang. It was Bobbie, of course. He didn’t apologize.

“Reggie,” he said, “I’ve got the goods now sure. It’s just come to me. We saw those Terpsichorean Cats at a matinée, old scout.”

“Yes?” I said.

“Well, don’t you see that that brings it down to two days? It must have been either Wednesday the seventh or Saturday the tenth.”

“Yes,” I said, “if they didn’t have daily matinées at Weinstein’s.”

I heard him give a sort of howl.

“Bobbie,” I said. My feet were freezing, but I was fond of him.

“Well?”

“I’ve remembered something too. It’s this. The day you went to Weinstein’s I lunched with you both at the Piazza. You had forgotten to bring your roll with you, so you wrote a check.”

“But I’m always writing checks.”

“Sure. But this was for a hundred dollars and made out to the hotel. Hunt up your check-book and see how many checks for a hundred dollars, payable to the Piazza Hotel, you wrote out between May 5 and May 10.”

He gave a kind of gulp.

“Reggie,” he said, “you’re a genius. I’ve always said so. I believe you’ve got it. Hold the line.”

PRESENTLY he came back.

“Hello,” he said.

“I’m here,” I said.

“It was the eighth. Reggie, old man, I—”

“Fine,” I said. “Good night.”

It was working along into the small hours now, but I thought I might as well make a night of it and finish the thing up, so I called up a hotel near Washington Square.

“Put me through to Mrs. Cardew,” I said.

“Say, it’s pretty late,” said the man at the other end.

“And getting later every minute,” I said. “Get a move on.”

I waited patiently. I had missed my beauty-sleep and my feet had frozen hard, but I was past regrets.

“What is the matter?” said Mary’s voice.

“My feet are cold,” I said. “But I didn’t call you up to tell you that particularly. I’ve just been chatting with Bobbie, Mrs. Cardew.”

“Oh! Is that Mr. Pepper?”

“Yes. He’s remembered it, Mrs. Cardew.”

She gave a sort of scream. I’ve often thought how interesting it must be to be one of those Central girls. The things they must hear, don’t you know. Bobbie’s howl and gulp and Mrs. Bobbie’s scream and all about my feet and all that. Most interesting it must be.

“He’s remembered it?” she gasped.

“He’s got it pinned down for keeps,” I said.

“Did you tell him?”

“No.”

Well, I hadn’t.

“Mr. Pepper.”

“Yes?”

“Was he—has he been—was he very worried?”

I CHUCKLED. This was where I was scheduled to be the life and soul of the party.

“Worried! He was about the most worried thing between here and San Francisco. He has been worrying as if he was paid to do it by the nation. He has started in to worry after breakfast, and—”

Oh, well, you can never tell with women. My idea was that we should pass the rest of the night slapping each other on the back across the wire and telling each other what bully good conspirators we were, don’t you know. But I’d got just as far as this when she absolutely bit at me. I heard the snap. And then she said “Oh!” in that choked kind of way. And when a woman says “Oh!” like that it means all the bad words she’d love to say if she only knew them.

And then she cut loose.

“What brutes men are! What horrid brutes! How you could stand by and see poor dear Bobbie worrying himself into a fever when a word from you would have put everything right, I can’t—”

“But—”

“And you call yourself his friend! His friend!” (Metallic laugh, most unpleasant.) “It shows how one can be deceived. I used to think you a kind-hearted man.”

“But, say, when I suggested the thing, you thought it perfectly—”

“I thought it hateful, abominable.”

“But you said it was absolutely cork—”

“I said nothing of the kind. And if I did I didn’t mean it. I don’t wish to be unjust, Mr. Pepper, but I must say that to me there seems to be something positively fiendish in a man who can go out of his way to separate a husband from his wife simply in order to amuse himself by gloating over his agony—”

“But—!”

“When one single word would have—”

“But you made me promise not to—” I bleated.

“And if I did, do you suppose I didn’t expect you to have the sense to break your promise?”

I was through. I had no further observations to make. I hung up the receiver and crawled into bed.

I STILL see Bobbie when he comes to the club, but I do not visit. He is friendly, but he stops short of issuing invitations. I ran across Mary at the Horse Show last week, and her eyes went through me like a couple of bullets through a pat of butter. And as they came out the other side, and I limped off to piece myself together again, there occurred to me the simple epitaph which, when I am no more, I intend to have inscribed on my tombstone. It was this: “He was a man who acted from the best motives. There is one born every minute.”

Notes:

See the British magazine version of this story from the Strand magazine, with annotations and the Strand illustrations by Joseph Simpson RBA, and a web transcription of this story with dynamic footnotes showing the significant variants between the British and American texts.

All book collections, as far as I know, reprint the Strand version of the story, so this Collier’s text will be new to many readers. It has many of the Americanisms that Wodehouse loved to record: piquant turns of phrase that were sometimes watered down for British readers (in many cases, I suspect, by editors at the Strand rather than by Wodehouse himself, although some of the British variants do seem to have his deliberate comic touch as well).

Notes for the American version:

Absent Treatment: the doctrine that a Christian Science practitioner need not be physically present to be of healing benefit to a patient. Famously satirized by Mark Twain in Christian Science (1899).

feel like thirty cents: The earliest citation found in Google Books for this phrase is a lyric in George Ade’s 1902 musical comedy The Sultan of Sulu: “R-E-M-O-R-S-E! / Those dry Martinis did the work for me; / Last night at twelve I felt immense, / To-day I feel like thirty cents.”

bonehead: US slang for a fool, a variant of blockhead; earliest OED citation is 1908, so this was a recent coinage

between the Battery and Harlem: the southern and northern ends of Manhattan Island; between them is the heart of New York City

silly ass: Not just a foolish person, but one of some social status; an “upper-class twit” in Monty Pythonesque terms. Bobbie’s wealth is implied here more than directly stated; he belongs to the same club as Reggie, who has inherited a wad and has never worked; Bobbie shops at Tiffany’s, and so forth. In the British version Bobbie plays polo, an expensive sport requiring the upkeep of horses.

wad: US slang for a roll of paper currency

admire anyone who earns a living, especially a girl: Wodehouse’s positive attitudes toward working women were remarkably feminist for his time (see especially Joan Valentine in Something New/Something Fresh). Some have attributed this to his marriage to Ethel in 1914, a widow who had had to support herself and her daughter. But this earlier story shows that he had this point of view before meeting her.

Sioux Falls … Reno: At a time when divorce in New York and most other states was time-consuming and expensive, a person whose marriage had failed might take up temporary residency in another place with more lenient laws. In the Dakota Territory, divorce could be granted on a number of grounds to those who had lived there for 90 days; Sioux Falls was the most popular destination because it had good railroad access and was a big enough town to have pleasant amenities. After statehood for South Dakota in 1889, religious activists pushed for a six-month, then a one-year residency requirement by 1909, moving the epicenter of the divorce industry to Reno, Nevada, which still had a six-month requirement. (Later, in competition with Idaho and Arkansas, Nevada would reduce its waiting period to a mere six weeks by 1931.)

love’s young dream: a reference to Thomas Moore’s poem of that title; “But there’s nothing half so sweet in life / As love’s young dream.”

phone down to the kitchen: This tells us that Bobbie and Mary live in a service flat: an apartment house for the well-to-do who want to be cared for by maids, valets, and cooks employed by the building management to serve the residents.

chicken at a camp-meeting: On the American rural frontier, camp meetings were religious revival gatherings, often lasting several days, with attendees staying in tents and the like. One supposes that a stray chicken would quickly find its way into the communal stew pot.

no pikers—they go the limit: In this sense, from 19th-century American slang, a piker is a cautious or fearful gambler who only makes small bets rather than the maximum bet allowed by the table rules; here, women like Mary, when roused, don’t chide timidly but use the full force of their eloquence.

ten-spot: a ten-dollar bill. A rough equivalent to $250 in 2017 values.

come from Missouri … want to be shown: Natives of Missouri (like the present annotator) have a reputation for skepticism, popularized (though probably not invented) by Congressman Willard Vandiver in 1899, who declared in a speech that “frothy eloquence neither convinces nor satisfies me. I’m from Missouri, and you have got to show me.”

all quiet along the Potomac: From a Civil War poem by Ethel Lynn Beers first published in Harper’s Weekly, November 30, 1861, as “The Picket Guard”; later set to music by J. H. Hewitt.

down to the cherry: Were Reggie and Bobbie alternating Manhattan cocktails with dry Martinis? No wonder their brain cells were on strike.

pure rye: American whiskey distilled from a fermented mash of at least 51 percent rye or a Canadian whisky of similar character which need not actually contain rye as an ingredient.

alcohol may be a food: Like sugar, its close chemical relative, alcohol contains calories but no significant other nutritive value. Bertie Wooster mentions that his Uncle George “discovered that alcohol was a food well in advance of modern medical thought.” In fact, the medical debate on this topic was well under way in the 1860s and continued into the first decade of the twentieth century, by which time its metabolism in moderate quantities was firmly established as energy-producing, like other carbohydrates, and therefore potentially fattening. But Wodehouse is likely to have learned about this from George Ade, in More Fables (1900): “Mr. Byrd … discovered that Alcohol was a Food long before the Medical Journals got onto it.”

peacherino: by extension from “peach” for something fine, this is something (or especially some woman) that is particularly fine. OED has US slang citations from 1900 on.

rubbering: looking (a shortening of “rubbernecking”); US slang from 1896 (the first OED citation is from George Ade).

Weinstein’s: This apparently is fictional, unlike the real Coliseum variety theatre named in the British version; it might be an echo of Hammerstein’s.

Piazza: More than likely to be an Italianate pseudonym for the real Plaza Hotel, opened 1907 near the southeast corner of Central Park in midtown Manhattan.

hotel near Washington Square: Wodehouse himself was living at the Hotel Earle (now the Washington Square Hotel) at the time this was written.

Horse Show: Not the event currently held in Central Park, but rather the National Horse Show founded in 1883 in New York (now moved to Kentucky). The prestige of the classic NHS was such that its 1887 directory of members formed the nucleus of the first New York Social Register; its president in 1909 was Alfred G. Vanderbilt.

there is one born every minute: In P. T. Barnum’s phrase, there is a sucker born every minute.

—Notes by Neil Midkiff

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums