Cosmopolitan, June 1910

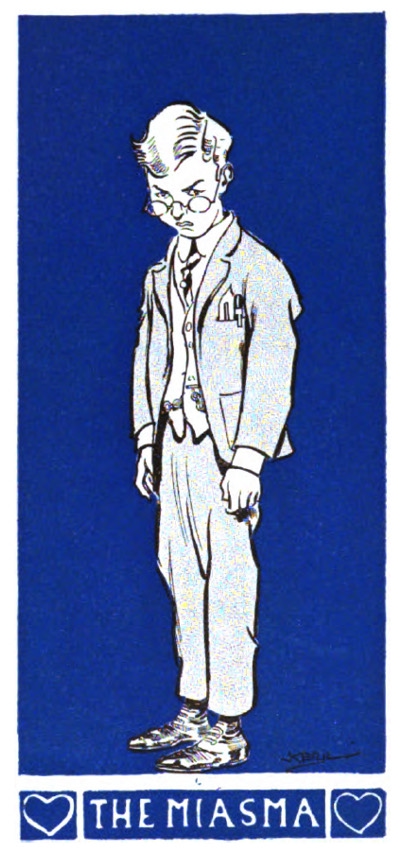

LTHOUGH this story is concerned principally with the Man and the

Maid, the Miasma pervades it to such an extent that I feel justified in

putting his name on the bills. Webster’s Dictionary defines the

word “miasma” as “an infection floating in the air;

a deadly exhalation”; and, in the opinion of Mr. Robert Ferguson,

his late employer, that description, though perhaps a little too flattering,

on the whole summed up Master Roland Bean pretty satisfactorily. Until

the previous day he had served Mr. Ferguson in the capacity of office-boy;

but there was that about Master Bean which made it practically impossible

for anyone to employ him for long. A syndicate of Galahad, Parsifal, and

Marcus Aurelius might have done it; but to an ordinary, erring man, conscious

of things done which should not have been done and of other things, equally

numerous, left undone, he was too oppressive. One conscience is enough

for any man. The employer of Master Bean had to cringe before two. Nobody

can last long against an office-boy whose eyes shine with quiet, respectful

reproof through gold-rimmed spectacles, whose manner is that of a middle-aged

saint, and who obviously knows all the Plod-and-Punctuality books by heart

and orders his life by their precepts. Master Bean was a walking edition

of “Stepping-stones to Success,” “Presidents Who Have

Never Chewed,” and “Young Man, Get up Early.” Galahad,

Parsifal, and Marcus Aurelius, as I said, might have remained tranquil

in his presence, but Robert Ferguson found the contract too large. After

one month he had braced himself up with a series of cocktails, and fired

the Punctual Plodder.

LTHOUGH this story is concerned principally with the Man and the

Maid, the Miasma pervades it to such an extent that I feel justified in

putting his name on the bills. Webster’s Dictionary defines the

word “miasma” as “an infection floating in the air;

a deadly exhalation”; and, in the opinion of Mr. Robert Ferguson,

his late employer, that description, though perhaps a little too flattering,

on the whole summed up Master Roland Bean pretty satisfactorily. Until

the previous day he had served Mr. Ferguson in the capacity of office-boy;

but there was that about Master Bean which made it practically impossible

for anyone to employ him for long. A syndicate of Galahad, Parsifal, and

Marcus Aurelius might have done it; but to an ordinary, erring man, conscious

of things done which should not have been done and of other things, equally

numerous, left undone, he was too oppressive. One conscience is enough

for any man. The employer of Master Bean had to cringe before two. Nobody

can last long against an office-boy whose eyes shine with quiet, respectful

reproof through gold-rimmed spectacles, whose manner is that of a middle-aged

saint, and who obviously knows all the Plod-and-Punctuality books by heart

and orders his life by their precepts. Master Bean was a walking edition

of “Stepping-stones to Success,” “Presidents Who Have

Never Chewed,” and “Young Man, Get up Early.” Galahad,

Parsifal, and Marcus Aurelius, as I said, might have remained tranquil

in his presence, but Robert Ferguson found the contract too large. After

one month he had braced himself up with a series of cocktails, and fired

the Punctual Plodder.

Yet now he was sitting in his

office in the Monroe Building, long after the last clerk had left, long

after the hour at which he himself was wont to leave, his mind full of

his late employee. Was this remorse? Was he longing for the touch of the

vanished hand, the gleam of the departed spectacles? He was not. His mind

was full of Master Bean because Master Bean was waiting for him in the

outer office; and he lingered on at his desk, after the day’s work

was done, for the same reason. Word had been brought to him earlier in

the evening that Master Roland Bean would like to see him. The answer

to that was easy: “Tell him I’m busy.” Master Bean’s

admirably dignified reply was that he understood how great was the pressure

of Mr. Ferguson’s work, and that he would wait till he was at liberty.

Liberty! Talk of the liberty of the treed ’possum, but do not use

the word in connection with a man bottled up in an office with a Roland

Bean guarding the only exit.

Yet now he was sitting in his

office in the Monroe Building, long after the last clerk had left, long

after the hour at which he himself was wont to leave, his mind full of

his late employee. Was this remorse? Was he longing for the touch of the

vanished hand, the gleam of the departed spectacles? He was not. His mind

was full of Master Bean because Master Bean was waiting for him in the

outer office; and he lingered on at his desk, after the day’s work

was done, for the same reason. Word had been brought to him earlier in

the evening that Master Roland Bean would like to see him. The answer

to that was easy: “Tell him I’m busy.” Master Bean’s

admirably dignified reply was that he understood how great was the pressure

of Mr. Ferguson’s work, and that he would wait till he was at liberty.

Liberty! Talk of the liberty of the treed ’possum, but do not use

the word in connection with a man bottled up in an office with a Roland

Bean guarding the only exit.

Mr. Ferguson kicked the waste-paper basket savagely. The unfairness of the thing hurt him. A fired office-boy ought to stay fired. It was not playing the game.

A slight cough penetrated the door between the two offices. Mr. Ferguson rose and grabbed his hat. Perhaps a sudden rush. . . . He shot out with the tense concentration of one moving toward the bacon-and-cabbage haven at a station where the train stops nine minutes.

“Good evening, sir,” was the watcher’s view-halloo.

“Ah, Bean,” said Mr. Ferguson, bucking center. “You still here? I thought you had gone. I’m afraid I cannot stop now—some other time—” He was almost through.

“I fear, sir, that you will be unable to get out,” said Master Bean sympathetically. “The building is locked up.”

Men who have been hit by bullets say that the first sensation is merely a sort of dull shock. So it was with Mr. Ferguson. He stopped in his tracks, and stared.

“The porter closes the door at seven o’clock punctually, sir. It is now nearly twenty minutes after the hour.”

Mr. Ferguson’s brain was still in the numbed stage. “Closes the door?” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“Then how are we to get out?”

“I fear we cannot get out, sir.”

Mr. Ferguson digested this.

“I am no longer in your employment, sir,” said Master Bean respectfully, “but I hope that in the circumstances you will permit me to remain here during the night.”

“During the night!”

“It would enable me to sleep more comfortably than on the stairs.”

“But we can’t stop here all night,” said Mr. Ferguson feebly. He had anticipated an unpleasant five minutes in Master Bean’s company. Imagination boggled at the thought of an unpleasant thirteen hours. He collapsed into a chair.

“I called,” said Master Bean, shelving the trivial subject of the prospective vigil, “in the hope that I might persuade you, sir, to reconsider your decision in regard to my dismissal. I can assure you, sir, that I am extremely anxious to give satisfaction. If you would take me back and inform me how I have fallen short, I would endeavor to improve. I—”

“We can’t stop here all night,” interrupted Mr. Ferguson, bounding from his chair, and beginning to pace the floor.

“Without presumption, sir, I feel that if you were to give me another chance, I should work to your satisfaction. I should endeavor—”

Mr. Ferguson stared at him in dumb horror. He felt like a rabbit in the coils of a python. This fearful boy, trained from his cradle on the literature of Purpose and Tenacity, could stick to his subject for hours at a stretch. Fatigue was a sensation unknown to the students of “Young Man, Get up Early.” Youth, condition—everything was in his opponent’s favor. He had a momentary vision of a sleepless night spent in listening to a nicely polished speech for the defense. He was seized with a mad desire for flight. He could not leave the building, but he must get away somewhere and think.

He dashed from the room, and raced up the dark stairs. And as he arrived at the next floor his eye was caught by a thin pencil of light which proceeded from a door on the left. No shipwrecked mariner on a desert island could have welcomed the appearance of a sail with greater enthusiasm. He bounded at the door. He knew to whom the room belonged. It was the office of one Blaythwayt, a real-estate man, and Blaythwayt was not only an acquaintance but a sport. Quite possibly there might be a deck of cards on Blaythwayt’s person, to help to pass the long hours. And if not, at least he would be company and his office a refuge. He flung open the door without going through the formality of knocking. Etiquette is not for the marooned.

“Say, Blaythwayt,” he began, and stopped abruptly. The only occupant of the room was a girl. “I beg your pardon,” he said, “I thought—” He stopped again. His eyes, dazzled with the light, had not seen clearly. They did so now. “You!” he cried.

The girl looked at him, first

with surprise, then with a cool hostility. “Good evening,”

she said.

The girl looked at him, first

with surprise, then with a cool hostility. “Good evening,”

she said.

“What are you doing here?” he demanded.

“I thought my doings had ceased to interest you,” she said. “I am Mr. Blaythwayt’s stenographer.”

“Do you know we are locked in?” he said.

He had expected wild surprise and dismay. She merely clicked her tongue in an annoyed manner.

“Again!” she said. “What a nuisance. I was locked in only a week ago.”

He looked at her with unwilling respect, the respect of the novice for the veteran. She was nothing to him now, of course. She had passed out of his life. But he could not help remembering that long ago what he had admired most in her had been this same spirit, this game refusal to be disturbed by fate’s blows. It braced him up. Here was he behaving as if some cataclysmal disaster had occurred just because he would have to sleep in a chair instead of a bed. It would not do. He sat down.

“So you’ve left the stage?” he said.

“I thought we agreed, when we parted, not to speak to each other.”

“Did we? I thought it was only to meet as strangers.”

“It’s the same thing.”

“Is it? I often talk to strangers.”

“What a bore they must think you,” she said, hiding one-eighth of a yawn with the tips of two fingers. “I suppose,” she went on with faint interest, “you talk to them in trains when they are trying to read their paper?”

“I don’t force my conversation on anyone.

“Don’t you?” she said, raising her eyebrows in sweet surprise. “Only your company, is that it?”

“Are you alluding to the present occasion?”

“Well, you have an office of your own in this building, I believe.”

“I have,” he said.

“Then why—”

“I am at perfect liberty,” he said with dignity, “to sit in my friend Blaythwayt’s office if I choose. I wish to see Mr. Blaythwayt.”

“On business?”

He proved that she had established

no corner in raised eyebrows. “I fear,” he said, “that

I cannot discuss my affairs with Mr. Blaythwayt’s employees. I must

see him personally.”

He proved that she had established

no corner in raised eyebrows. “I fear,” he said, “that

I cannot discuss my affairs with Mr. Blaythwayt’s employees. I must

see him personally.”

“Mr. Blaythwayt is not here.”

“I will wait.”

“He will not be here for thirteen hours.”

“I’ll wait.”

“Very well,” she burst out, “you have brought it on yourself. You’ve only yourself to blame. If you had been good and gone back to your office, I would have brought you down some cake and cocoa.”

“Cake and cocoa!” said he superciliously.

“Yes, cake and cocoa,” she snapped. “It’s all very well for you to turn up your nose at them now, but wait. You’ve thirteen hours of this in front of you. I know what it is. Last time I had to spend the night here I couldn’t get to sleep for hours, and when I did I dreamed that I was chasing dill pickles round and round Union Square. And I never caught them, either. Long before the night was finished I would have given anything for even a dry cracker. I made up my mind I’d always keep something here in case I ever got locked in again. Yes, smile. You’d better, while you can.”

He was smiling, but wanly. Nobody but a professional fasting-man could have looked unmoved into the inferno she had pictured. Then he rallied.

“Cake!” he said scornfully.

She nodded grimly.

“Cocoa!”

Again that nod, ineffably sinister.

“I’m afraid I don’t care for slops,” he said.

“If you will excuse me,” she said indifferently, “I have a little work that I must finish.”

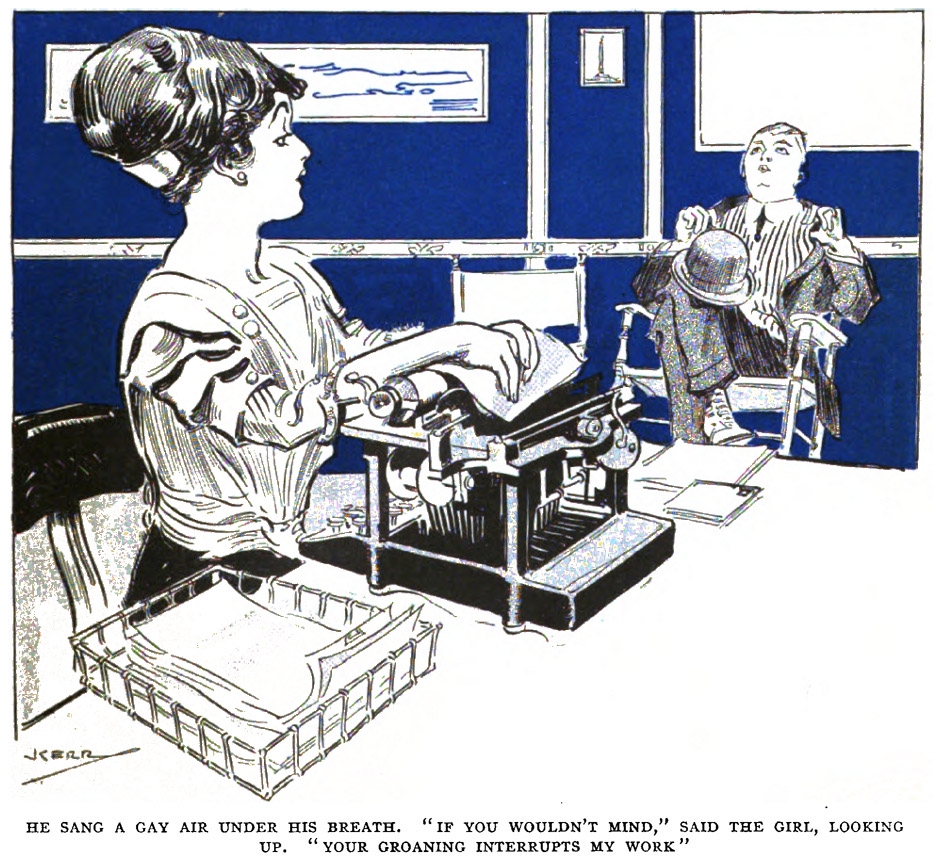

She turned to her desk, leaving him to his thoughts. They were not exhilarating. He had maintained a brave front, but inwardly he quailed. Reared in the country, he had developed at an early age a fine, healthy appetite. Once, soon after his arrival in New York, he had allowed a dangerous fanatic to persuade him that the secret of health was to go without breakfast. His lunch that day had cost him three forty-five, and only decent shame had kept the figure as low as that. He knew perfectly well that, long ere the dawn of day, his whole soul would be crying out for cake, squealing frantically for cocoa. Would it not be better to—No, a thousand times no. Death, but not surrender. His self-respect was at stake. Looking back, he saw that his entire relations with this girl had been a series of battles of will. So far, though he had certainly not won, he had not been defeated. He must not be defeated now. He crossed his legs, and sang a gay air under his breath.

“If you wouldn’t mind,” said the girl, looking up.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Your groaning interrupts my work.”

“I was not groaning. I was singing.”

“Oh? I’m sorry.”

“Not at all.”

Eight bars rest.

Mr. Ferguson, deprived of the solace of song, filled in the time by gazing at the toiler’s back hair. It set in motion a train of thought, an express-train bound for the land of yesterday. It recalled days in the woods, evenings on the porch. It recalled sunshine—and storm. Plenty of storm—minor tempests that burst from a clear sky, apparently without cause, and the great, final tornado. There had been cause enough for that. Why was it, mused Mr. Ferguson, that every girl in every country town in every state of the Union who had ever recited “Paul Revere’s Ride” well enough to escape lynching at the hands of a church sociable was seized with the desire to come to New York and go on the stage? He sighed.

“Please don’t snort,” said a frigidly cold voice.

There was a train-wreck in the land of yesterday. Mr. Ferguson, the only survivor, limped back into the present.

The present had little charm, but at least it was better than the cakeless future. He fixed his thoughts on it. He wondered how Master Bean was passing the time. Probably doing deep-breathing exercises or reading a pocket Aristotle.

The girl pushed back her chair and rose. She went to a small closet in a corner of the room, and from it produced in instalments all that goes to make cake and cocoa. She did not speak. Presently, filling space, there sprang into being an odor; and as it reached him Mr. Ferguson stiffened in his chair, bracing himself as for a fight to the death. It was more than an odor. It was the soul of the cocoa, singing to him. His fingers gripped the arms of the chair. This was the test.

The girl separated a section of cake from the parent body. She caught his eye.

“You had better go,” she said. “If you go now, it’s just possible that I may— But I forgot. You don’t like slops.”

“No,” said he resolutely, “I don’t.”

She seemed now in the mood for conversation. “I wonder why you came up here at all?” she said.

“There’s no reason why you shouldn’t know. I came up here because my late office-boy is down-stairs.”

“Why should that send you up here?”

“You’ve never met him or you wouldn’t ask. Have you ever had to face some one who is simply incarnate saintliness and disapproval? Who—”

“Are you forgetting that I was engaged to you for several weeks?”

He was too startled to be hurt. The idea of himself as a Roland Bean was too new to be assimilated immediately. It called for meditation.

“Was I like that?” he said at last, almost humbly.

“You know you were. Oh, I’m not thinking only about your views on the stage. It was everything. Whatever I did you were there to disapprove like a—like a—like an aunt,” she concluded triumphantly. “You were too good for anything. If only you had, just once, done something wrong, I think I’d have— But you couldn’t. You’re simply perfect.”

A man will remain cool and composed under many charges. Hint that his tastes are criminal, and he will shrug his shoulders. But accuse him of goodness and you rouse the lion.

Mr. Ferguson’s brow darkened. “As a matter of fact,” he said haughtily, “I was to have had supper with a chorus-girl this very night.”

“How very appalling!” said she languidly.

She sipped her cocoa.

“I suppose you consider that quite terrible?” she said.

“For a beginner.”

She crumbled her cake. Suddenly she looked up. “Who is she?” she demanded.

“I beg your pardon?” he said, coming out of a pleasant reverie.

“Who is this girl?”

“She—er—her name—her name is Marie—Marie Templeton.”

She seemed to think for a moment. “That dear old lady?” she said. “I know her quite well.”

“What!” he exclaimed.

“ ‘Mother’ we used to call her. Have you met her son?”

“Her son?”

“A rather nice-looking man. He plays heavy parts in stock. He’s married and has two of the cutest children. Their grandmother is devoted to them. Hasn’t she ever mentioned them to you?”

She poured herself out another cup of cocoa. Conversation again languished.

“I suppose you’re very fond of her?” she said at length.

“I’m crazy about her.” He paused. “Dear little thing,” he added.

She rose, and moved to the door. There was a nasty gleam in her eyes.

“You aren’t going?” he said.

“I shall be back in a moment. I’m going to fetch your poor little office-boy up here. He must be missing you.”

He sprang up, but she had gone. Leaning over the banister, he heard a door open below, then a short conversation, and finally footsteps climbing the stairs.

It was pitch dark on the landing. He stepped aside, and they passed without seeing him. Master Bean was discoursing easily on cocoa, the processes whereby it was manufactured and the remarkable distances which natives of Mexico had covered with it as their only food. The door opened, flooding the landing with light, and Mr. Ferguson, stepping from ambush, began to descend the stairs.

The girl came to the banister. “Mr. Ferguson?”

He stopped. “Did you want me?” he asked.

“Are you going back to your office?”

“I am. I hope you will enjoy Bean’s society. He has a fund of useful information on all subjects.”

He went on. After a while she returned to the room, and closed the door. Mr. Ferguson went into his office, and sat down.

There was once a person of the name of Simeon Stylites who took up a position on top of a pillar and stayed there, having no other engagements, for thirty years. Mr. Ferguson, who had read Tennyson’s poem on the subject, had until to-night looked upon this as going some. Reading the lines,

—thrice ten years,

Thrice multiplied by superhuman pangs,

In hungers and in thirsts, fever and cold,

In coughs, aches, stitches, ulcerous throes and cramps,

Patient on this tall pillar I have borne

Rain, wind, frost, heat, hail, damp, and sleet, and snow,

he had gathered, roughly as it were, that Simeon had not been comfortable. He had pitied him. But now, sitting in his office-chair, he began to wonder what the man had made such a fuss about. He suspected him of having had a yellow streak. It was not as if he had not had food. He had talked about “hungers and thirsts,” but he must have had something to eat, or he could not have stayed the course. Very likely, if the truth were known, there was somebody below who passed him up regular supplies of—cake and cocoa. . . . He began to look on Simeon as an overrated amateur.

He changed his position. It was one of the peculiarities of his chair that, almost immediately after he seemed to have discovered a comfortable position, some outlying portion of his anatomy developed either an ache, a stitch, an ulcerous throe, or a cramp, necessitating a general readjustment. And as for “rain, wind, frost, heat, hail, damp, and sleet, and snow,” it was a late-November night, and the steam-heat had been turned off.

Sleep refused to come to him. It got as far as his feet, but no farther. He rose, and stamped to restore the circulation. It was at this point that he definitely condemned Simeon Stylites as a Sybaritic four-flusher.

If this were one of those realistic, Zolaesque stories, I would describe the crick in the back that— But let us hurry on.

It was about six hours later—he had no watch, but the number of aches, stitches, and ulcerous throes that he had experienced, not to mention cramps, could not possibly have been condensed into a shorter period—that his manly spirit snapped. Let us not judge him too harshly. The girl up-stairs had broken his heart, ruined his life, and practically compared him to Roland Bean, and his pride should have built up an impassable wall between them; but—she had cake and cocoa. In similar circumstances King Arthur would have groveled before Guinevere.

He rushed to the door, and tore it open. There was a startled exclamation from the darkness outside.

“I hope I didn’t disturb you,” said a small, meek voice.

Mr. Ferguson did not answer. His twitching nostrils were drinking in a familiar aroma.

“Were you asleep? May I come in? I’ve brought you some cake and cocoa.”

He took the rich gifts

from her in silence. There are moments in a man’s life too sacred

for words. The wonder of the thing had struck him dumb. An instant before,

and he had had but a desperate hope of winning these priceless things

from her at the cost of all his dignity and self-respect. He had been prepared

to secure them through a shower of biting taunts, a blizzard of razor-like

“I told you so’s.” Yet here he was, draining the cup,

and still able to hold his head up, look the world in the face, and call

himself a man.

He took the rich gifts

from her in silence. There are moments in a man’s life too sacred

for words. The wonder of the thing had struck him dumb. An instant before,

and he had had but a desperate hope of winning these priceless things

from her at the cost of all his dignity and self-respect. He had been prepared

to secure them through a shower of biting taunts, a blizzard of razor-like

“I told you so’s.” Yet here he was, draining the cup,

and still able to hold his head up, look the world in the face, and call

himself a man.

His keen eye detected a crumb on his coat-sleeve. This retrieved and consumed, he turned to her, seeking explanation.

She was changed. The battle-gleam had faded from her eyes. She seemed scared and subdued. Her manner was of one craving comfort and protection. “That awful boy!” she breathed.

“Bean?” said Mr. Ferguson.

“He’s frightful.”

“I thought you might get a little tired of him. What has he been doing?”

“Talking. I feel battered. He’s like one of those awful encyclopedias that give you a sort of dull, leaden feeling in your head directly you open them. Do you know how many tons of water go over Niagara Falls every year?”

“No.”

“He does.”

“I told you he had a fund of useful information. The Purpose-and-Tenacity books insist on it. That’s how you catch your employer’s eye. One morning the boss suddenly wants to know how many rubber-plants there are in Brooklyn, or the number of somnambulists in Philadelphia. You tell him, and he takes you into partnership. Later, you become president. But I haven’t thanked you for the cocoa. It was fine.”

He waited for the retort, but it did not come. A pleased wonderment filled him. Could these things really be thus?

“And it isn’t only what he says,” she went on. “I know what you mean about him now. It’s his accusing manner.”

“I’ve tried to analyze that manner. I believe it’s the spectacles.”

“It’s frightful. When he looks at you, you think of all the wrong things you’ve ever done or ever wanted to do.”

“Does he have that effect on you?” he said excitedly. “Why, that exactly describes what I feel.”

The affinities looked at each other. She was the first to speak.

“We always did think alike on most things, didn’t we?” she said.

“Of course we did.”

He shifted his chair forward. “It was all my fault,” he said. “I mean, what happened.”

“It wasn’t. It—”

“Yes, it was. I want to tell you something. I don’t know if it will make any difference now, but I should like you to know it. It’s this. I’ve altered a good deal since I came to New York. For the better, I think. I’m a pretty poor sort of specimen still, but at least I don’t imagine I can measure life with a foot-rule. I don’t judge the world any longer by the standards of a jay town. New York has knocked some of the corners off me. I don’t think you would find me the Bean type any longer. I don’t disapprove of other people much now. Not as a habit. I find I have enough to do keeping myself up to schedule.”

“I want to tell you something, too. I expect it’s too late, but never mind. I want you to hear it. I’ve altered, too, since I came to New York. I used to think the universe had been invented just to look on and wave its hat while I did great things. New York has put a large, cold piece of ice against my head, and the swelling has gone down. I’m not the girl with ambitions any longer. I just want to keep my job and not have too bad a time when the day’s work’s over.”

He came nearer to where she sat. “We said we would meet as strangers, and we do. We never have known each other. Don’t you think we had better get acquainted?” he said.

There was a respectful tap at the door.

“Come in,” snapped Mr. Ferguson. “Well?”

Behind the gold-rimmed spectacles of Master Bean there shone a softer look than usual, a look rather complacent than disapproving.

“I must apologize, sir, for intruding upon you. I am no longer in your employment, but I hope that in the circumstances you will forgive my entering your private office. Thinking over our situation just now, an idea came to me by means of which I fancy we might be enabled to leave the building.”

“What!”

“It occurred to me, sir, that by telephoning to police headquarters—”

“Good heavens!” cried Mr. Ferguson. “I never thought of it!”

Two minutes later he replaced the receiver.

“It’s all right,” he said. “I’ve made them understand the trouble. They’re bringing a ladder. I wonder what the time is? It must be about four in the morning.”

Master Bean produced a nickel-plated watch. “The time, sir, is almost exactly half-past ten.”

“Half-past ten! We must have been here longer than three hours. Your watch is wrong.”

“No, sir. I am very careful to keep it exactly right. I do not wish to run any risk of being unpunctual.”

“Half-past ten!” cried Mr. Ferguson. “Why, we’re in loads of time to look in some place for supper. This is great.”

“Supper! I thought—” She stopped.

“What’s that? Thought what?”

“Hadn’t you an engagement for supper?”

He stared at her. “Whatever gave you that idea? Of course not.”

“I thought you were taking Miss Templeton—”

“Miss Temp— Oh!” His face cleared. “Oh, there isn’t such a person. I invented her. I had to when you accused me of being like our friend the Miasma. Legitimate self-defense. Hello, give me 0430 Bryant.”

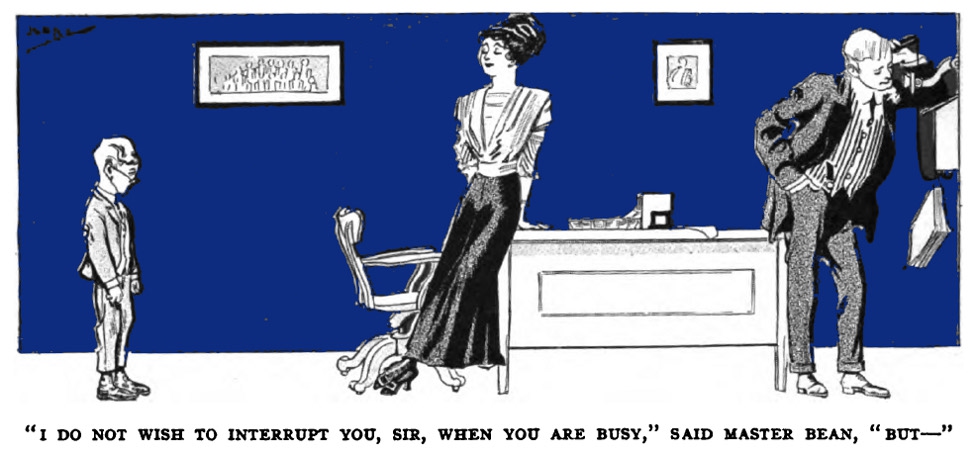

“I do not wish to interrupt you, sir, when you are busy,” said Master Bean, “but—”

“Come and see me to-morrow morning,” said Mr. Ferguson.

“Bob,” said the girl, as the first threatening mutter from the orchestra heralded an imminent storm of melody, “when that boy comes to-morrow, what are you going to do?”

“Call up the police reserves. How about some oysters?”

“No, but you must do something. We shouldn’t have been here but for him.”

“That’s true.” He pondered. “I’ve got it. I’ll get him a job with Raikes & Courtenay.”

“Why Raikes & Courtenay?”

“Because I have a pull with them. But principally,” said Mr. Ferguson with a devilish grin, “because they are in San Francisco. San Francisco is three thousand miles from New York, and they have earthquakes there.”

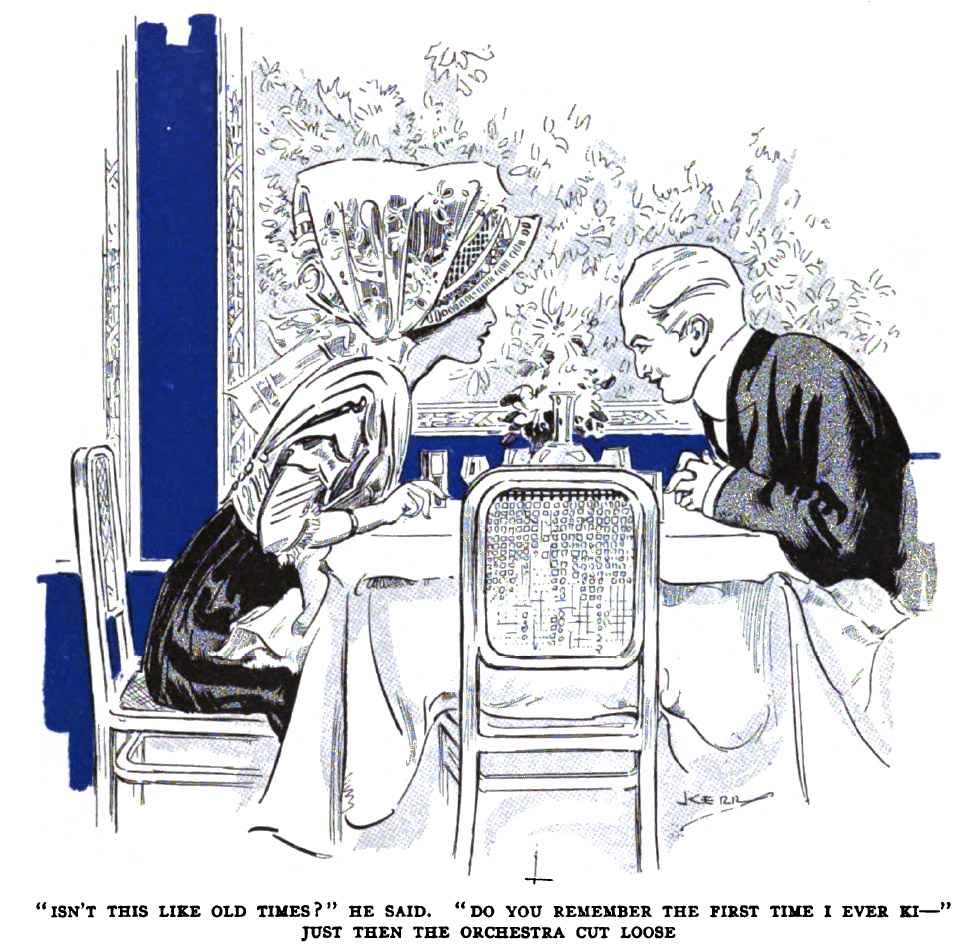

He bent across the table. “Isn’t this like old times!” he said. “Do you remember the first time I ever ki—”

Just then the orchestra cut loose.

Note: Thanks to Neil Midkiff for providing the transcription of this story.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums