Cosmopolitan, June 1920

THE morning was fair; the sky was blue, and the sun shone genially upon New York as Archie Moffam, arm in arm with his young friend, Reginald van Tuyl, sauntered into Broadway. For the first time since he had married Lucille, the only daughter of Daniel Brewster, millionaire proprietor of the Cosmopolis Hotel, things had begun to break right for Archie. Relations between himself and his father-in-law had at last been placed upon a satisfactory footing.

“The relief, dear old bean,” he said to Reggie, “is something terrific. It seems that old Brewster—a fellow who absolutely has to be seen to be believed—had hoped for a different sort of son-in-law, and I am revealing no secrets when I say that, on my rolling in and trying to dig a father’s blessing out of him, he nearly expired on the door-mat. True, he put me up at the Cosmopolis and let me sign for my meals, but, apart from that, he was far from matey—very, very far! Oh, far indeed! However, just as I was getting fed to the gills with my sufferings and beginning to crack under the strain, I’m dashed if there wasn’t a happy ending. Absolutely! A regular close-up and slow fade-out of Virtue Triumphant. You see, the old boy is most fearfully keen on building another hotel, and he’d got the site and what-not when he suddenly discovered that one of the waiters he’d sacked from the Cosmopolis—great pal of mine—owned a shop in the very middle of it and wouldn’t sell. I offered to intercede, bit his ear for three thousand of the best and crispest to buy the shop, bought it, and then told him that I wouldn’t sell unless he chucked his imitation of Simon Legree and became matey. So now everything’s fine. The Dove of Peace flaps its little wings— Hello, old lad, what’s the matter?”

Archie broke off his recital abruptly. A sort of spasm had passed across his companion’s features. The hand holding Archie’s arm had tightened convulsively. One would have said that Reginald had received a shock.

“It’s nothing,” said Reggie. “I’m all right now. I caught sight of that fellow’s clothes rather suddenly. They shook me a bit. I’m all right now,” he said bravely.

Archie followed his friend’s gaze, and understood. Reggie van Tuyl was never at his strongest in the morning, and he had a sensitive eye for clothes. He had been known to resign from clubs because members exceeded the bounds in the matter of soft shirts with dinner jackets. And the short, thick-set man who was standing just in front of them in an attitude of restful immobility was certainly no dandy. Take him for all in all and on the hoof, he might have been posing as a model for a sketch of “What the Well-Dressed Man Should Not Wear.”

In costume, as in most other things, it is best to take a definite line and stick to it. This man had obviously vacillated. His neck was swathed in a green scarf; he wore an evening-dress coat, and his lower limbs were draped in a pair of tweed trousers built for a larger man. To the north, he was bounded by a straw hat; to the south, by brown shoes.

Archie surveyed the man’s back carefully.

“Bit thick!” he said sympathetically. “But, of course, Broadway isn’t Fifth Avenue. What I mean to say is, bohemian license and what-not. Broadway’s crammed with deuced brainy devils who don’t care how they look. Probably this bird is a master mind of some species strayed from Greenwich Village.”

“All the same, a man’s no right to wear an evening-dress coat with tweed trousers.”

“Absolutely not! I see what you mean.”

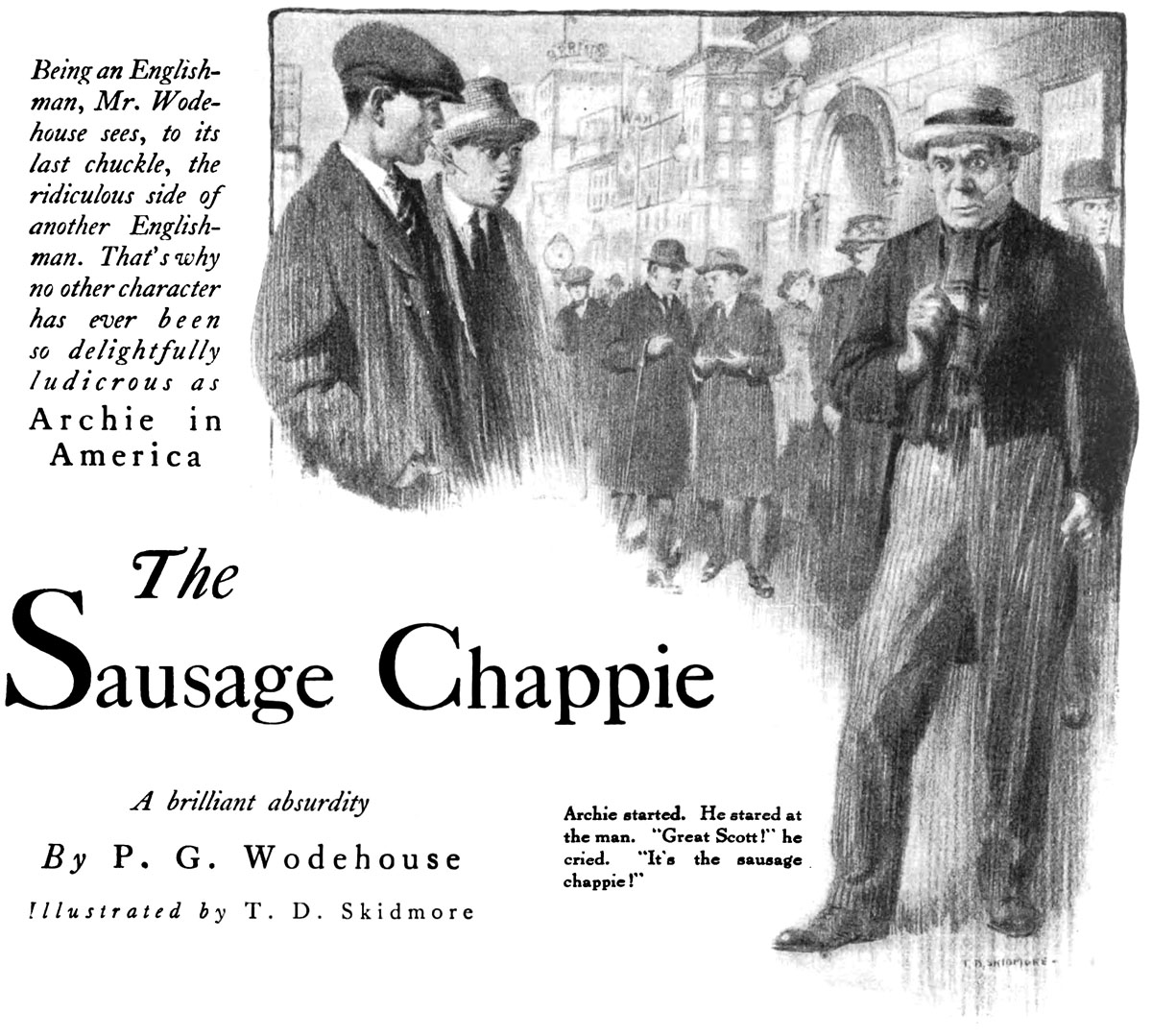

At this point, the sartorial offender turned. Seen from the front, he was even more unnerving. He appeared to possess no shirt, though this defect was offset by the fact that the tweed trousers fitted snugly under the arms. He was not a handsome man. At his best, he could never have been that, and in the recent past he had managed to acquire a scar that ran from the corner of his mouth half-way across his cheek. Even when his face was in repose, he had an odd expression; and when, as he chanced to do now, he smiled, “odd” became a mild adjective, quite inadequate for purposes of description. It was not an unpleasant face, however. Unquestionably genial, indeed. There was something in it that had a quality of humorous appeal.

Archie started. He stared at the man.

“Great Scott!” he cried. “It’s the sausage chappie!”

Reginald van Tuyl gave a little moan. He was not used to this sort of thing. A sensitive young man as regarded scenes, Archie’s behavior upset him. For Archie, releasing his arm, had bounded forward and was shaking the other’s hand warmly.

“Well, well, well! My dear old chap! You must remember me—what? No? Yes?”

The man with the scar seemed puzzled. He shuffled the brown shoes, patted the straw hat, and eyed Archie questioningly.

“I don’t seem to place you,” he said.

Archie slapped the back of the evening-dress coat.

“We met outside St. Mihiel in the war. You gave me a bit of sausage. One of the most sporting events in history. Nobody but a real sportsman would have parted with a bit of sausage at that moment to a stranger. Never forgotten it, by Jove! Saved my life—absolutely! Hadn’t chewed a morsel for eight hours. Well, have you got anything on? I mean to say, you aren’t booked for lunch or any rot of that species, are you? Fine! Then I move we all toddle off and get a bite somewhere.” He squeezed the other’s arm fondly. “Fancy meeting you again like this! I’ve often wondered what became of you. But, by Jove, I was forgetting. Dashed rude of me! My friend, Mr. van Tuyl.”

Reggie gulped. The longer he looked at it, the harder this man’s costume was to bear.

“Sorry,” he mumbled. “Just remembered— Important date— Late already— Er—see you sometime——”

He melted away, a broken man. Archie was not sorry to see him go. Reggie was a good chap, but he would undoubtedly have been de trop at this reunion.

“I vote we go to the Cosmopolis,” he said, steering his newly found friend through the crowd. “The browsing and sluicing isn’t bad there, and I can sign the bill, which is no small consideration nowadays.”

The sausage chappie chuckled amusedly.

“I can’t go to a place like the Cosmopolis looking like this.” Archie was a little embarrassed.

“Oh, I don’t know, you know, don’t you know?” he said. “Still, since you have brought the topic up in the course of general chit-chat, you did get the good old wardrobe a bit mixed this morning—what? I mean to say, you seem, absent-mindedly, as it were, to have got hold of samples from a good number of your various suitings.”

“ ‘Suitings?’ How do you mean—‘suitings?’ I haven’t any suitings! Who do you think I am? Vincent Astor? All I have is what I stand up in.”

Archie was shocked. This tragedy touched him. He himself had never had any money in his life, but, somehow, he had always seemed to manage to have plenty of clothes. How this was, he could not say. He had always had a vague sort of idea that tailors were kindly birds who never failed to have a pair of trousers or something up their sleeve to present to the deserving. There was the drawback, of course, that, once they had given you the things, they were apt to write you rather a lot of letters about it; but you soon managed to recognize their handwriting, and then it was a simple task to extract their communications from your morning mail and drop them in the waste-paper basket. This was the first case he had encountered of a man who was really short on clothes.

“My dear old lad,” he said briskly, “this must be remedied. Oh, positively! This must be remedied at once. I suppose my things wouldn’t fit you? No? Well, I tell you what. We’ll wangle something from my father-in-law. Old Brewster, you know, the fellow who runs the Cosmopolis. His’ll fit you like the paper on the wall, because he’s a tubby little blighter, too. What I mean to say is, he’s also one of those sturdy, square, fine-looking chappies of about the middle height.”

“I gather,” said the man with the scar, “that you have a pull with your father-in-law?”

“Absolutely! Quite the spoiled child and what-not! By the way, where are you stopping these days?”

“Nowhere just at present. I thought of taking one of those self-contained park benches.”

“Are you broke?”

“Am I!”

Archie was concerned.

“You ought to get a job.”

“I ought. But, somehow, I don’t seem able to.”

“What did you do before the war?”

“I’ve forgotten.”

“How do you mean—‘forgotten?’ You can’t mean—‘forgotten?’ ”

“Yes. It’s quite gone.”

“But I mean to say—you can’t have forgotten a thing like that!”

“Can’t I? I’ve forgotten all sorts of things. Where I was born. How old I am. Whether I’m married or single. What my name is——”

“Well, I’m dashed!” said Archie, staggered. “But you remembered about giving me a bit of sausage outside St. Mihiel.”

“No, I didn’t. I’m taking your word for it. For all I know, you may be luring me into some den to rob me of my straw hat. I don’t know you from Adam. But I like your conversation—especially the part about eating—and I’m taking a chance.”

Archie was concerned.

“Listen, old bean! Make an effort! You must remember that sausage episode. It was just outside St. Mihiel, about five in the evening. Your little lot were lying next to my little lot, and we happened to meet, and I said, ‘What ho?’ and you said, ‘Hullo!’ and I said: ‘What ho? What ho?’ and you said, ‘Have a bit of sausage?’ and I said: ‘What ho? What ho? What ho?’ ”

“The dialogue seems to have been darned sparkling, but I don’t remember it. It must have been after that that I stopped one. I don’t seem quite to have caught up with myself since I got hit.”

“Oh! That’s how you got that scar?”

“No. I got that jumping through a plate-glass window in London on Armistice night.”

“What on earth did you do that for?”

“Oh, I don’t know. It seemed a good idea at the time.”

“But if you can remember a thing like that, why can’t you remember your name?”

“I remember everything that happened after I came out of the hospital. It’s the part before that’s gone.”

Archie patted him on the shoulder.

“I know just what you want. You need a bit of quiet and repose, to think things over and so forth. You mustn’t go sleeping on park benches. Won’t do at all! Not a bit like it! You must shift to the Cosmopolis. It isn’t half a bad spot, the old Cosmop.”

“Is the Cosmopolis giving free board and lodging these days?”

“Rather! Take it from me—I’ve had some. That’ll be all right. My father-in-law’s frightfully keen on me. Refuse me nothing. Well, this is the spot. We’ll start by trickling up to the old boy’s suite and looking over his reach-me-downs. I know the waiter on his floor. He’ll let us in with his pass-key.”

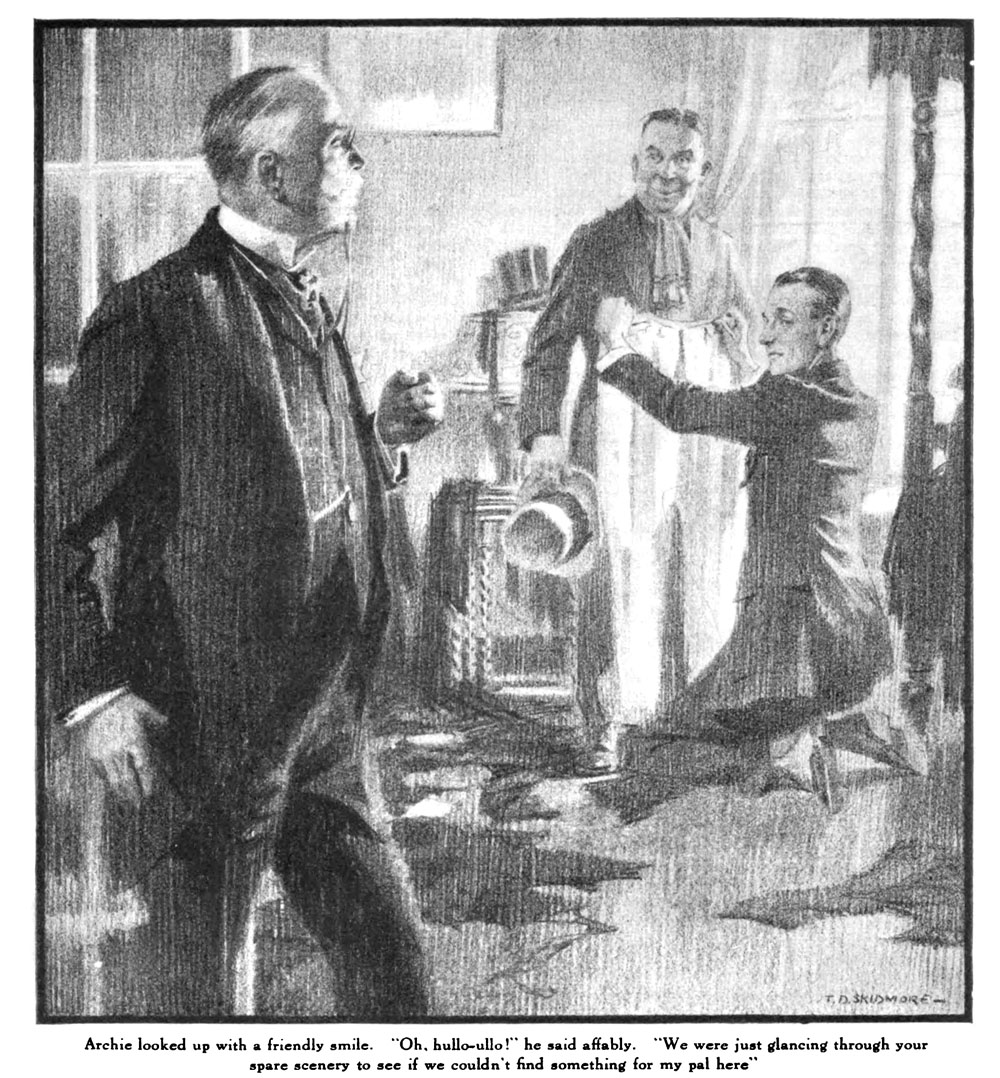

And so it came about that Mr. Daniel Brewster, returning to his suite in the middle of lunch in order to find a paper dealing with the subject he was discussing with his guest, the architect of his new hotel, was aware of a murmur of voices behind the closed door of his bedroom. Recognizing the accents of his son-in law, he breathed an oath and charged in.

The sight that met his eyes when he opened the door did nothing to soothe him. The floor was a sea of clothes. And in the middle of this welter was Archie, with a man who, to Mr. Brewster’s heated eye, looked like a tramp comedian out of a burlesque show.

“Great Godfrey!” ejaculated Mr. Brewster.

Archie looked up with a friendly smile.

“Oh, hullo-ullo!” he said affably. “We were just glancing through your spare scenery to see if we couldn’t find something for my pal here. This is Mr. Brewster, my father-in-law, old man.” Archie scanned his relative’s twisted features. Something in his expression seemed not altogether encouraging. He decided that the negotiations had better be conducted in private. “One moment, old lad,” he said, to his new friend; “I just want to have a little talk with my father-in-law in the other room. Just a little friendly business chat. You stay here.”

In the other room, Mr. Brewster turned on Archie like a wounded lion of the desert.

“What the——”

Archie secured one of his coat buttons and began to massage it affectionately.

“Ought to have explained,” said Archie. “Only, didn’t want to interrupt your lunch. The sportsman on the horizon is a dear old pal of mine——”

Mr. Brewster wrenched himself free.

“What do you mean, you angleworm, by bringing tramps into my bedroom and messing about with my clothes?”

“That’s just what I’m trying to explain, if you’ll only listen. This bird is a bird I met in France during the war. He gave me a bit of sausage outside St. Mihiel. He can’t remember who he is or where he was born or what his name is, and he’s broke, so, dash it, I must look after him. You see, he gave me a bit of sausage.”

Mr. Brewster’s frenzy gave way to an ominous calm.

“I’ll give him two seconds to clear out of here. If he isn’t gone by then, I’ll have him thrown out.”

Archie was shocked.

“But you don’t understand. You haven’t grasped the good old situash. This chappie has lost his memory because he was wounded in the war. Keep that fact firmly fixed in the old bean. He fought for you—fought and bled for you. Bled profusely, by Jove! And he saved my life!”

“If I’d got nothing else against him, that would be enough!”

“But you can’t sling a chappie out into the cold, hard world who bled in gallons to make the world safe for the Hotel Cosmopolis! Think of all he went through!”

Mr. Brewster looked ostentatiously at his watch.

“Two seconds!” he said.

There was a silence. Archie appeared to be thinking.

“Right-o!” he said, at last. “No need to get the wind up. I know where he can go. It’s just occurred to me. I’ll put him up at my little shop.”

The purple ebbed from Mr. Brewster’s face. Such was his emotion that he had forgotten that infernal shop. He sat down. There was more silence. Then,

“I knew you would be reasonable about it,” said Archie approvingly. “Now, honestly, as man to man, how do we go?”

“What do you want me to do?” growled Mr. Brewster.

“I thought you might put the chappie up for a while, and give him a chance to look round and nose about a bit.”

“I absolutely refuse to give any more loafers free board and lodging.”

“Any more?”

“Well, he would be the second, wouldn’t he?”

Archie looked pained.

“It’s true,” he said, “that, when I first came here, I was temporarily resting, so to speak; but didn’t I go right out and grab the managership of your new hotel? Positively!”

“I will not adopt this tramp.”

“Well, find him a job, then.”

“What sort of job?”

“Oh, any old sort.”

“He can be a waiter if he likes.”

“But I say, you know,” said Archie doubtfully, “this chappie is a gentleman, you know.”

“Oh, indeed! Then, perhaps, he would rather be manager of the hotel.”

“That’s a sound idea! I’ll ask him.”

Mr. Brewster exploded.

“Listen: I’ll give your dilapidated friend two seconds to decide if he wants to be a waiter or not. If he doesn’t, he knows the way out.”

“That ‘two seconds’ thing seems to be a perfect obsession with you. All right; I’ll put the matter before him.”

He returned to the bedroom. The sausage chappie was gazing fondly into the mirror with a spotted tie draped round his neck.

“I say, old top,” said Archie apologetically, “the Emperor of the Cooties out yonder isn’t in one of his sunniest moods to-day. Don’t know why. He has delivered what you might call a jolly old ultimatum. He says you can have a job here as waiter, and he won’t do another dashed thing for you. How about it?”

“Do waiters eat?”

“I suppose so. Though, by Jove, come to think of it, I’ve never seen one at it.”

“That’s good enough for me,” said the sausage chappie. “When do I begin?”

The sausage chappie made rather a good waiter. He was brisk and attentive, and did the work as if he liked it. But Archie, brooding on his case, was not satisfied. Something seemed to tell him that the man was fitted for higher things, and, as the days went by, it began to seem to him that it was he, Archie Moffam, who had been selected by destiny to find the other’s real place in the sun. Archie was a grateful soul. That sausage, coming at the end of a five-hour hike, had made a deep impression on his plastic nature. Reason told him that only an exceptional man could have parted with half a sausage at a moment when half-sausages were worth considerably more than their weight in gold, and he could not feel that a job as waiter at a New York hotel was an adequate job for an exceptional man. Of course, the root of the trouble lay in the fact that the fellow couldn’t remember what his real life-work had been before the war. It was exasperating to reflect, as the other moved away from his table to take his order to the kitchen, that there—for all one knew—went the dickens of a lawyer or doctor or architect or what-not, debarred from the exercise of his legitimate profession by the mere accident of having received a section of a German shell in the side of his head. The thing kept Archie awake at night.

One night, when he was not awake—it was, as a matter of fact, four o’clock in the morning—he was jerked from sleep by the ringing of the telephone-bell. He drowsily unhooked the receiver. The voice of the sausage chappie sounded at the other end of the wire.

“Hello! Is that you?”

“Absolutely!” said Archie.

“It’s a trifle late,” said the sausage chappie.

“No, no!” said Archie courteously. “Any time you’re passing.”

“I wanted to tell you I’ve just remembered something. I was born in—half a minute—I’ve forgotten again.”

Archie held the receiver patiently.

“Hello!” said the sausage chappie.

“On the spot!” said Archie.

“Springfield, Ohio,” said the sausage chappie.

“I say, that’s fine—what? Congratulations, old top! Anything else?”

“Nothing at present. But I feel as if a sort of mist were beginning to lift. I’m expecting further dope any minute.”

“Splendid! Stick to it, old bean; stick to it!”

Archie hung up the receiver. He was thrilled. He wanted to chat about this extraordinary affair with some one. He unhooked the receiver again.

“Number, please,” said the girl at the switchboard.

“I say, will you put me through to Mr. Brewster’s room.” Presently the sleep-laden voice of his father-in-law greeted him.

“Hello!”

“Oh, hello!” said Archie. “Is that you? I say, isn’t it topping? You know our pal with the groggy memory—the one you lent your blue suit to? Well——”

“What are you talking about?”

“I’m just telling you. You remember the bird you gave the waiter job to? The sausage chappie, you know. Well, he’s just remembered he was born in Springfield, Ohio.”

There was a long pause at the other end of the wire.

“Did you get me out of bed at four in the morning,” said Mr. Brewster, in a strained voice, “to tell me that?”

“I thought you would be glad to know.”

Mr. Brewster hung up the receiver without a word. There were no words, in or out of the dictionary, which would have even begun to express his feelings. He might have done it in Russian, but he knew no Russian. He was not interested in the sausage chappie’s birthplace. He was, indeed, sorry the sausage chappie had been born at all. And he was still sorrier that Archie Moffam had been born. He had long since come to look on that event as one of the worst calamities the world had ever seen.

Something of this view-point he expressed to Archie by word of mouth in the lobby of the hotel later, when he met the latter on his way to lunch in the grill-room. And it was in a somewhat subdued mood that Archie finally extracted himself from the machinery and passed on. He sank down in his favorite corner in a frame of mind comparable to that of one who has been kicked in the head by a mule and run over by a motor-truck.

The grill-room had begun to fill up. The sausage chappie was attending to a table farther down the room, at which a woman with a small boy in a sailor-suit had seated themselves. The woman was engrossed with the bill of fare, but the child’s attention seemed riveted upon the sausage chappie.

“Mummie,” he asked interestedly, as the man disappeared toward the kitchen, “why has that man got such a funny face?”

“Hush, darling!”

“Yes; but why has he?”

“I don’t know, darling.”

The child’s faith in the maternal omniscience seemed to have received a shock. He had the air of a seeker after truth who has been baffled. His eye roamed the room discontentedly.

“He’s got a funnier face than that man there,” he said, pointing at Archie.

“Hush, darling!”

“But he has! Much funnier!”

In a way, it was a sort of compliment, but Archie felt embarrassed. He buried himself behind the bill of fare. Presently, the sausage chappie returned, attended to the needs of the woman and the child, and came over to Archie. Archie ordered a chop. The sausage chappie booked the item, added French fried potatoes on his own responsibility, and then, dismissing business for the moment, became communicative.

“I had a big night last night,” he said, leaning on the table.

“That’s good!” said Archie. “The old bean beginning to stir a bit—what?”

“I should say so! Something seems to have happened to the works. Just before I went to sleep, I remembered my name as well.”

Archie forgot his troubles in his excitement.

“I say—that’s topping! What is your name?”

“Why, it’s—that’s funny. It’s gone again. I have an idea it began with an S. What was it? Skeffington? Skillington?”

“Sanderson?”

“No; I’ll get it in a moment. Cunningham? Carrington? Wilberforce? Debenham?”

“Dennison?” suggested Archie helpfully.

“No, no, no! It’s on the tip of my tongue. Barrington? Montgomery? Hepplethwaite? I’ve got it! Smith!”

“By Jove! Really?”

“Certain of it.”

“What’s the first name?”

An anxious expression came into the man’s eyes. He hesitated. He lowered his voice.

“I have a horrible feeling that it’s Lancelot!”

“Good God!” said Archie.

“It couldn’t really be that, could it?”

Archie looked grave. He hated to give pain, but he felt he must be honest.

“It might,” he said. “People give their children all sorts of rummy names.”

The head waiter began to drift up like a bank of fog, and the sausage chappie returned to his professional duties. When he came back, bearing the chop and potatoes, he was beaming again.

“Something else I remembered,” he said, removing the cover. “I’m married.”

“Good Lord!”

“At least, I was before the war. She had blue eyes and brown hair and a Pekingese dog.”

“What was her name?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, you’re coming on,” said Archie. “You only need patience. Everything comes to him who waits.” Archie sat up, electrified. “I say, by Jove, that’s rather good—what? Everything comes to him who waits, and you’re a waiter—what, what? I mean to say—what?”

“Mummie,” said the child at the other table, still speculative, “do you think something trod on his face?”

“Hush, darling!”

“Perhaps it was bitten by something.”

“Eat your nice fish, darling,” said the mother, who seemed to be one of those dull-witted persons whom it is impossible to interest in a discussion on first causes.

Archie attacked his chop vigorously. He felt stimulated. Not even the advent of his father-in-law, who came in a few moments later and sat down at the other end of the room, could depress his spirits. He champed his chop with an appetite.

The sausage chappie came to his table again.

“It’s a funny thing,” he said. “Like waking up after you’ve been asleep. Everything seems to be getting clear. The dog’s name was Marie. My wife’s dog, you know. And she had a mole on her chin.”

“The dog?”

“No. My wife. Little beast. She bit me in the leg once.”

“Your wife?”

“No. The dog.”

Archie scanned the bill of fare.

“How about a chunk of French pastry and a demi-tasse?” he said. “Yes; I rather think that’s what the doctor ordered.”

“Good Lord!” said the sausage chappie.

Archie looked up. The exclamation could hardly be intended for a commentary on his choice of provender, for the other, who always took a kindly and constructive interest in his meals, had himself suggested a bit of French pastry when bringing the chop. Some deeper emotion than disapproval was plainly working within him. Archie followed his gaze.

A couple of tables away, next to a sideboard on which the management exposed for view the cold meats and puddings and pies mentioned in volume two of the bill of fare—Buffet Froid—a man and a girl had just seated themselves. The man was stout and middle-aged. He bulged in practically every place in which a man can bulge, and his head was almost entirely free from hair. The girl was young and pretty. Her eyes were blue. Her hair was brown. She had a rather attractive little mole on the left side of her chin.

“Good Lord!” said the sausage chappie.

“Now what?” said Archie.

“Who’s that? Over at the table there?”

Archie, through long attendance at the Cosmopolis grill, knew most of the habitués by sight.

“That’s a man named Gossett. James J. Gossett. He’s a motion-picture man. You must have seen his name around.”

“I don’t mean him. Who’s the girl?”

“I’ve never seen her before.”

“It’s my wife!” said the sausage chappie.

“Your wife?”

“Yes.”

“Well, well, well!” said Archie. “Many happy returns of the day!”

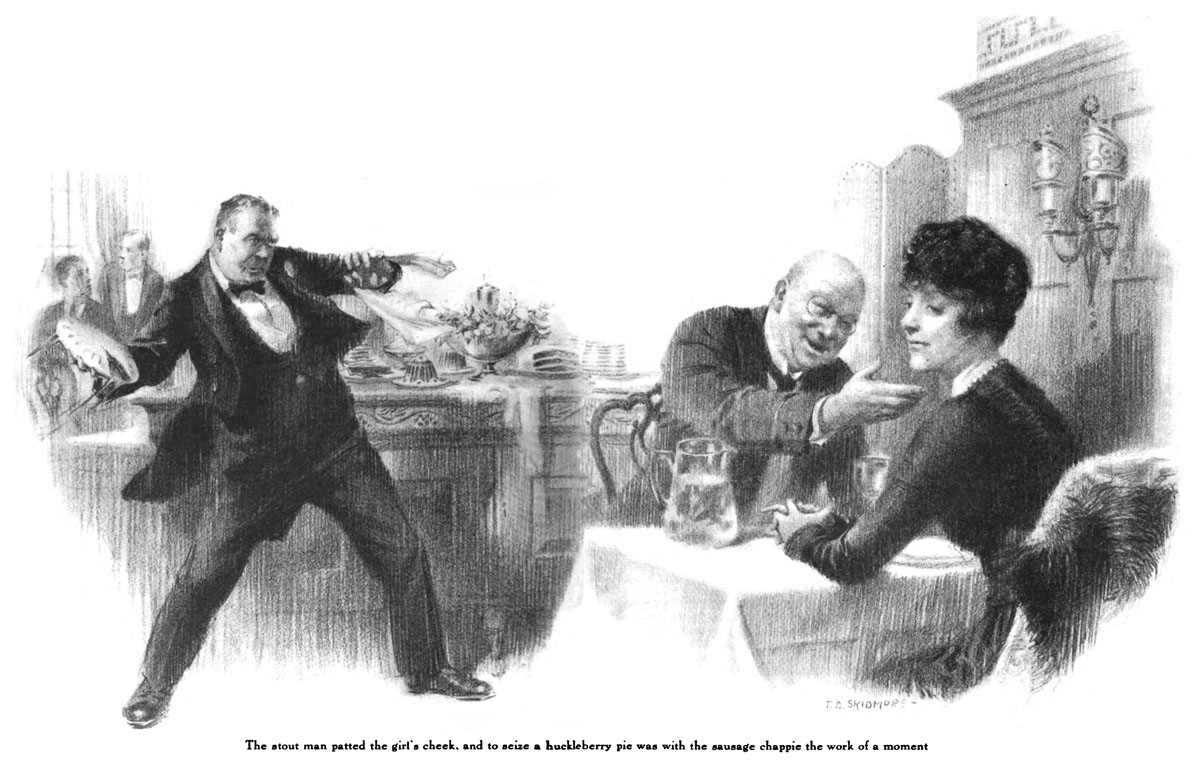

At the other table, the girl, unconscious of the drama which was about to enter her life, was engrossed in conversation with the stout man. And at this moment, the stout man leaned forward and patted her on the cheek.

It was a paternal pat—the pat which a genial uncle might bestow on a favorite niece—but it did not strike the sausage chappie in that light. He had been advancing on the table at a fairly rapid pace, and now he bounded forward with a hoarse cry.

Archie was at some pains to explain to his father-in-law later that, if the management left cold pies and things about all over the place, this sort of thing was bound to happen sooner or later. He urged that it was putting temptation in people’s way and that Mr. Brewster had only himself to blame. Whatever the rights of the case, the Buffet Froid undoubtedly came in remarkably handy at this crisis in the sausage chappie’s life. He had almost reached the sideboard when the stout man patted the girl’s cheek, and to seize a huckleberry pie was with him the work of a moment. The next instant, the pie had whizzed past the other’s head and burst like a shell against the wall.

There are, no doubt, restaurants where this sort of thing would have excited little comment, but the Cosmopolis was not one of them. Everybody had something to say. Mr. Brewster bounded from his seat and bellowed incoherently. Waiters discussed the matter animatedly among themselves in the background. The girl uttered a scream, the stout man an expletive. The only one among those present who had anything sensible to say was the child in the sailor-suit.

“Do it again!” said the child cordially.

The sausage chappie did it again. He took up a fruit salad, poised it for a moment, then decanted it over Mr. Gossett’s bald head. The child’s happy laughter rang over the restaurant. Whatever anybody else might think of the affair, this child liked it, and was prepared to go on record to that effect.

Epic events have a stunning quality. They paralyze the faculties. For a moment, there was a pause. The world stood still. Mr. Brewster bubbled inarticulately. Mr. Gossett dried himself sketchily with a napkin. The sausage chappie snorted. The girl had risen to her feet and was staring wildly.

“John!” she cried.

Even at this moment of crisis, the sausage chappie was able to look relieved.

“So it is!” he said. “And I thought it was Lancelot!”

“I thought you were dead!”

“I’m not,” said the sausage chappie.

Mr. Gossett, speaking thickly through the fruit salad, was understood to say that he regretted this. And then confusion broke loose again. Everybody began to talk at once.

“I say!” said Archie. “I say! One moment!”

Of the first stages of this interesting episode, Archie had been a paralyzed spectator. The thing had numbed him. But when he reached the gesticulating group, he was calm and business-like. He had a constructive policy to suggest.

“I say,” he said; “I’ve got an idea.”

“Go away!” said Mr. Brewster.

Archie quelled him with a gesture.

“Leave us,” he said. “We would be alone. I want to have a little business talk with Mr. Gossett.” He turned to the movie magnate, who was gradually emerging from the fruit-salad rather after the manner of a stout Venus rising from the sea. “Can you spare me a moment of your valuable time?”

“I’ll have him arrested!”

“Don’t you do it, laddie! Listen!”

“The man’s mad! Throwing pies!”

Archie attached himself to his coat button.

“Be calm, laddie! Calm and reasonable!”

For the first time, Mr. Gossett seemed to become aware that what he had been looking on as a vague annoyance was really an individual.

“Who are you?”

Archie drew himself up with dignity.

“I am this gentleman’s representative,” he replied, indicating the sausage chappie with a motion of the hand. “His jolly old personal representative. I act for him. And, on his behalf, I have a pretty ripe proposition to lay before you. By Jove, you ought to rise up and embrace this bird! He has thrown pies at you, hasn’t he? Very well. You are a movie magnate. Your whole fortune is founded on chappies who throw pies. You probably scour the world for chappies who throw pies. Yet, when one comes right to you without any fuss or trouble, and demonstrates before your very eyes the fact that he is without a peer as a pie-propeller, you get the wind up and talk about having him arrested. Consider! Be sensible! Why let your personal feelings stand in the way of doing yourself a bit of good? Give this chappie a job, and give it him quick, or we go elsewhere. Did you ever see Fatty Arbuckle handle pastry with a surer touch? Has Charlie Chaplin got this fellow’s speed and control? Absolutely not! I tell you, old friend, you’re in danger of throwing away a good thing.” He paused. The sausage chappie beamed.

“I’ve always wanted to go into the movies,” he said. “I was an actor before the war. Just remembered.”

Mr. Brewster attempted to speak. Archie waved him down.

“How many times have I got to tell you not to butt in?” he said severely.

Mr. Gossett’s militant demeanor had become a trifle modified during Archie’s harangue. First and foremost a man of business, Mr. Gossett was not insensible to the arguments which had been put forward.

He mused a while.

“How do I know this fellow would screen well?” he said, at last.

“ ‘Screen well!’ ” cried Archie. “Of course he’ll screen well! Look at his face! I ask you! The map! I call your attention to it!” He turned apologetically to the sausage chappie. “Awfully sorry, old lad, for dwelling on this, but it’s business, you know.” He turned to Mr. Gossett. “Did you ever see a face like that? Of course not! Why should I, as this gentleman’s personal representative, let a face like that go to waste? There’s a fortune in it. By Jove, I’ll give you two minutes to think the thing over, and, if you don’t talk business then, I’ll jolly well take my man straight round to Mack Sennett or some one. We don’t have to ask for jobs. We consider offers.”

There was a silence. And then the clear voice of the child in the sailor-suit made itself heard again.

“Mummie!”

“Yes, darling?”

“Is the man with the funny face going to throw any more pies?”

“No, darling.”

The child uttered a scream of disappointed fury.

“I want the funny man to throw some more pies!”

A look almost of awe came into Mr. Gossett’s face. He had heard the voice of the public. He had felt the beating of the public’s pulse.

“Out of the mouths of babes and sucklings,” he said reverently. “Out of the mouths of babes and sucklings. Come round to my office.”

The next escapade of Archie in America will appear in July Cosmopolitan.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums