Liberty, March 12, 1927

SOMEBODY had left a copy of an illustrated weekly paper in the bar parlor of the Anglers’ Rest, and, glancing through it, I came upon the ninth full-page photograph of a celebrated musical-comedy actress that I had seen since the preceding Wednesday. This one showed her looking archly over her shoulder with a rose between her teeth, and I flung the periodical from me with a stifled cry.

“Tut, tut!” said Mr. Mulliner reprovingly. “You must not allow these things to affect you so deeply. Remember, it is not actresses’ photographs that matter, but the courage which we bring to them.”

He sipped his hot Scotch.

“I wonder if you have ever reflected,” he said gravely, “what life must be like for the men whose trade it is to make pictures. Statistics show that the two classes of the community which least often marry are milkmen and fashionable photographers—milkmen because they see women too early in the morning, and fashionable photographers because their days are spent in an atmosphere of feminine loveliness so monotonous that they become surfeited and morose. I know of none of the world’s workers whom I pity more sincerely than the fashionable photographer; and yet it is the ambition of every youngster who enters the profession some day to become one.

“At the outset of his career, you see, a young photographer is sorely oppressed by human gargoyles, and gradually this begins to prey upon his nerves.

“ ‘Why is it,’ I remember my cousin Clarence asking, after he had been about a year in the business, ‘that all these misfits want to be photographed? Why do men with faces which you would think they would be anxious to hush up wish to be strewn about the country on whatnots and in albums? I started out full of ardor and enthusiasm and my eager soul is being crushed. This morning the Mayor of Tooting East came to make an appointment. He is coming tomorrow afternoon to be taken in his cocked hat and robes of office, and there is absolutely no excuse for a man with a face like that perpetuating his features. I wish to goodness I was one of those fellows who only take camera portraits of beautiful women.’

“His dream was to come true sooner than he had imagined. Within a week the great test case of Biggs vs. Mulliner had raised my cousin Clarence from an obscure studio in West Kensington to the position of London’s most famous photographer.

“You possibly remember the case? The events that led up to it were, briefly, as follows:

JNO. HORATIO BIGGS, O. B. E., the newly elected Mayor of Tooting East, alighted from a cab at the door of Clarence Mulliner’s studio at four-ten on the afternoon of June the seventeenth. At four-eleven he went in. And at four-sixteen and a half he was observed shooting out of a first-floor window, vigorously assisted by my cousin, who was prodding him in the seat of the trousers with the sharp end of a photographic tripod. Those who were in a position to see stated that Clarence’s face was distorted by a fury scarcely human.

A week later the case of Biggs vs. Mulliner had begun, the plaintiff claiming damages to the extent of ten thousand pounds and a new pair of trousers. And at first things looked very black for Clarence.

It was the speech of Sir Joseph Bodger, K. C., for the defense, that turned the scale.

“I do not,” said Sir Joseph, addressing the jury on the second day, “propose to deny the charges that have been brought against my client. We freely admit that on the seventeenth instant we did jab the defendant with our tripod in a manner to cause alarm and despondency. But, gentlemen, we plead justification. The whole case turns upon one question: Is a photographer entitled to assault—either with or, as the case may be, without a tripod—a sitter who, after being warned that his face is not up to the minimum standard requirements, insists upon remaining in the chair and moistening the lips with the tip of the tongue? Gentlemen, I say Yes!

“Unless you decide in favor of my client, gentlemen of the jury, photographers—debarred by law from the privilege of rejecting sitters—will be at the mercy of anyone who comes along with the price of a dozen photographs in his pocket. You have seen the plaintiff, Biggs. You have noted his broad, slablike face, intolerable to any man of refinement and sensibility. You have observed his walrus mustache, his double chin, his protruding eyes. Take another look at him, and then tell me if my client was not justified in chasing him with a tripod out of that sacred temple of Art and Beauty, his studio.

“Gentlemen, I have finished. I leave my client’s fate in your hands with every confidence that you will return the only verdict that can conceivably issue from twelve men of your obvious intelligence, your manifest sympathy, and your superb breadth of vision.”

The jury decided in Clarence’s favor without leaving the box; and the crowd waiting outside to hear the verdict carried him shoulder high to his house, refusing to disperse until he had made a speech and sung Photographers Never, Never, Never Shall Be Slaves. And next morning every paper in England came out with leading articles commending him for having so courageously established, as it had not been established since the days of Magna Charta, the fundamental principle of the Liberty of the Subject.

The effect of this publicity on Clarence’s fortunes was naturally stupendous. He had become in a flash the best known photographer in the United Kingdom, and was now in a position to realize that vision which he had had of taking the pictures of none but the beaming and the beautiful. Every day the loveliest ornaments of Society and the Stage flocked to his studio; and it was with the utmost astonishment, therefore, that, calling upon him one morning on my return to England after an absence of two years in the East, I learned that fame and wealth had not brought him happiness.

I FOUND him sitting moodily in his studio, staring with dull eyes at a camera portrait of a well known actress in a bathing-suit. He looked up listlessly as I entered.

“Clarence!” I cried, shocked at his appearance. “What is wrong?”

“Everything,” he replied. “I’m fed up.”

“What with?”

“Life. Beautiful women. This beastly photography business.”

I was amazed. Rumors of his success had reached me. In every photographers’ club in the metropolis, from the Negative and Solution in Pall Mall to the humble public houses frequented by the men who do your picture while you wait, I had heard, he was being freely spoken of as the logical successor to the Presidency of the Amalgamated Guild of Bulb-Squeezers.

“I can’t stick it much longer,” said Clarence, tearing the camera portrait into a dozen pieces with a dry sob and burying his face in his hands. “Actresses nursing their dolls! Countesses simpering over kittens! Film stars among their books! . . . In ten minutes I go to catch a train at Waterloo. I have been sent for by the Duchess of Hampshire to take some studies of Lady Monica Southbourne in the castle grounds.”

A shudder ran through him. I patted him on the shoulder. He spoke on:

“And I bet she will want to be taken offering a lump of sugar to her dog, and the picture will appear in the Sketch and the Tatler as Lady Monica Southbourne and Friend.”

“Clarence, this is morbid.”

He was silent for a moment.

“Ah, well,” he said, pulling himself together with a visible effort, “I have made my sodium sulphite, and I must lie in it.”

I saw him off in a cab, looking, I thought, like an aristocrat of the French Revolution being borne off to his doom on a tumbrel. How little he guessed that the only girl in the world was waiting for him round the corner.

No, you are wrong. Lady Monica did not turn out to be the only girl in the world. If what I said caused you to expect that, I misled you. Lady Monica proved to be all his fancy had pictured her. In addition to her two dogs, which she was portrayed in the act of feeding with two lumps of sugar, she possessed a totally unforeseen pet monkey, of which he was compelled to take no fewer than eleven studies.

No, it was not Lady Monica who captured Clarence’s heart.

IT was in a traffic jam at the top of Whitehall that he first observed the girl. His cab had become becalmed in a sea of omnibuses. Within a few feet of him was another taxi. There was a face at its window. It turned toward him, and their eyes met.

IT was in a traffic jam at the top of Whitehall that he first observed the girl. His cab had become becalmed in a sea of omnibuses. Within a few feet of him was another taxi. There was a face at its window. It turned toward him, and their eyes met.

To Clarence, surfeited with the coy, the beaming, and the delicately chiseled, it was the most wonderful face he had ever looked at. All his life, he felt, he had been searching for something on these lines. That snub nose—those freckles—that breadth of cheekbone—the squareness of that chin—and not a dimple in sight. He told me afterward that his only feeling was one of incredulity. He had not believed the world contained women like this.

And then the traffic jam loosened up and he was carried away.

It was as he was passing the Houses of Parliament that the realization came to him that the strange bubbly sensation that seemed to start from just above the lower left side pocket of his waistcoat was not, as he had at first supposed, dyspepsia, but love. Yes, love had come at long last to Clarence Mulliner; and he loved a girl whom he probably would never see again.

Next day Clarence was back in his studio, diving into the velvet nose bag as of yore, and telling peeresses to watch the little birdie, just as if nothing had happened. And if there was now a strange, haunting look of pain in his eyes, nobody objected to that. Indeed, inasmuch as the grief that gnawed at his heart had the effect of deepening and mellowing his camera-side manner to an almost sacerdotal unctuousness, his private sorrows actually helped his professional prestige. Women told one another that being photographed by Clarence Mulliner was like undergoing some wonderful spiritual experience in a noble cathedral; and his appointment book became fuller than ever.

AND yet he was not happy. He had lost the only girl he had ever loved, and without her what was Fame? What was Affluence? What were the Highest Honors in the Land?

These were the questions he was asking himself one night as he sat in his library, somberly sipping a final whisky and soda before retiring.

He had asked them once and was just going to ask them again, when he was interrupted by the sound of someone ringing the front-door bell.

He rose, surprised. It was late for callers. The domestic staff had gone to bed, so he went to the door and opened it. A shadowy figure was standing on the steps.

“Mr. Mulliner?”

“I am Mr. Mulliner.”

The man stepped past him into the hall. And, as he did so, Clarence saw that he was wearing over the upper half of his face a black velvet mask.

“I must apologize for hiding my face, Mr. Mulliner,” the visitor said as Clarence led him to the library.

“Not at all,” replied Clarence courteously. “No doubt it is all for the best.”

“Indeed?” said the other, with a touch of asperity. “If you really want to know, I am probably the handsomest man in London. But my mission is one of such extraordinary secrecy that I dare not run the risk of being recognized.” He paused, and Clarence saw his eyes glint through the holes in the mask as he directed a rapid gaze into each corner of the library. “Mr. Mulliner, have you any acquaintance with the ramifications of international secret politics?”

With a gesture Clarence indicated his well stocked shelves.

“I have read everything E. Phillips Oppenheim ever wrote.”

“And you are a patriot?”

“I am.”

“Then I can speak freely. No doubt you are aware, Mr. Mulliner, that for some time past this country and a certain rival Power have been competing for the friendship and alliance of a certain other Power?”

“No,” said Clarence; “they didn’t tell me that.”

“Such is the case. And the President of this Power—”

“Which one?”

“The second one.”

“Call it B.”

“The President of Power B is now in London. He arrived incognito, traveling under an assumed name; and the representatives of Power A, to the best of our knowledge, are not yet aware of his presence. This gives us just the few hours necessary to clinch this treaty with Power B before Power A can interfere. I ought to tell you, Mr. Mulliner, that if Power B forms an alliance with this country, the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon race will be secured for hundreds of years. Whereas if Power A gets hold of Power B, civilization will be thrown into the melting-pot. In the eyes of all Europe—and when I say all Europe I refer particularly to Powers C, D, and E—this nation would sink to the rank of a fourth-class Power.”

“Call it Power F,” said Clarence.

“It rests with you, Mr. Mulliner, to save England.”

“Great Britain,” corrected Clarence. He is half Scotch on his mother’s side. “But how? What can I do about it?”

“The position is this: The President of Power B has an overwhelming desire to have his photograph taken by Clarence Mulliner. Consent to take it, and our difficulties will be at an end. Overcome with gratitude, he will sign the treaty, and the Anglo-Saxon race will be safe.”

CLARENCE did not hesitate. Apart from the natural gratification of feeling that he was doing the Anglo-Saxon race a bit of good, business was business; and if the President took a dozen of the large size finished in silver wash it would mean a nice profit.

“I shall be delighted,” he said.

“Your patriotism,” said the visitor, “will not go unrewarded. It will be gratefully noted in the very highest circles.”

Clarence reached for his appointment book.

“Now, let me see. Wednesday? No, I’m full up Wednesday. Thursday? No. Suppose the President looks in at my studio between four and five on Friday?”

The visitor uttered a gasp.

“Good heavens, Mr. Mulliner!” he exclaimed. “Surely you do not imagine that, with the vast issues at stake, these things can be done openly and in daylight? If the devils in the pay of Power A were to learn that the President intended to have his photograph taken by you, I would not give a straw for your chances of living an hour.”

“Then what do you suggest?”

“You must accompany me now to the President’s suite at the Milan Hotel. We shall travel in a closed car, and God send that those fiends did not recognize me as I came here. If they did, we shall never reach that car alive. Have you, by any chance, while we have been talking, heard the hoot of an owl?”

“No,” said Clarence; “no owls.”

“Then perhaps they are nowhere near. The fiends always imitate the hoot of an owl.”

“A thing,” said Clarence, “which I tried to do when I was a small boy and never seemed able to manage. The popular idea that owls say ‘Tu-whit, tu-whoo’ is all wrong. The actual noise they make is something far more difficult and complex, and it was beyond me.”

“Quite so.” The visitor looked at his watch. “Shall we be making a start?”

“Certainly.”

“Then follow me.”

It appeared to be holiday time for fiends, or else the night shift had not yet come on, for they reached the car without being molested. Clarence stepped in, and his masked visitor, after a keen look up and down the street, followed him.

“Talking of my boyhood—” began Clarence.

The sentence was never completed. A soft, wet pad was pressed over his nostrils; the air became a-reek with the sickly fumes of chloroform; and Clarence knew no more.

When he came to, he was lying on a bed in a room in a strange house. It was a medium-sized room with scarlet wall paper, simply furnished with a wash-hand stand, a chest of drawers, two cane-bottomed chairs, and a God Bless Our Home motto framed in oak. He was conscious of a severe headache, and was about to rise and make for the water bottle on the washstand, when, to his consternation, he discovered that his arms and legs were shackled with stout cord.

AS a family, the Mulliners have always been noted for their reckless courage; and Clarence was no exception to the rule. But for an instant his heart undeniably beat a little faster. He saw now that his masked visitor had tricked him. Instead of being a representative of His Majesty’s Diplomatic Service (a most respectable class of men), he had really been all along a fiend in the pay of Power A.

Clarence gritted his teeth and struggled vainly to loose the knots that secured his wrists. He had fallen back, exhausted, when he heard the sound of a key turning, and the door opened. Somebody crossed the room and stood by the bed, looking down at him.

The newcomer was a stout man with a complexion that matched the wall paper. He was puffing slightly, as if he had found the stairs trying. He had broad, slablike features; and his face was split in the middle by a walrus mustache. Somewhere and in some place, Clarence was convinced, he had seen this man before.

And then it all came back to him: An open window with a pleasant summer breeze blowing in; a stout man in a cocked hat trying to climb through this window; and he, Clarence, doing his best to help him with the sharp end of a tripod. It was Jno. Horatio Biggs, the Mayor of Tooting East.

A shudder of loathing ran through Clarence.

“Traitor!” he cried.

“Eh?” said the Mayor.

“If anybody had told me that a son of Tooting, nursed in the keen air of freedom that blows across the Common, would sell himself for gold to the enemies of his country, I would never have believed it. Well, you may tell your employers—”

“What employers?”

“Power A.”

“Oh, that?” said the Mayor. “I am afraid my secretary, whom I instructed to bring you to this house, was obliged to romance a little in order to insure your accompanying him, Mr. Mulliner. All that about Power A and Power B was just his little joke. If you want to know why you were brought here—”

Clarence uttered a low groan.

“I have guessed your ghastly object, you ghastly object,” he said quietly. “You want me to photograph you.”

The Mayor shook his head.

“Not myself. I realize that that can never be. My daughter.”

“Does she take after you?”

“People tell me there is a resemblance.”

“I refuse,” said Clarence.

“Think well, Mr. Mulliner.”

“I have done all the thinking that is necessary. England—or, rather, Great Britain—looks to me to photograph only her fairest and loveliest. History has yet to record an instance of a photographer playing his country false, and Clarence Mulliner is not the man to supply the first one. I decline your offer.”

“I wasn’t looking on it exactly as an offer,” said the Mayor thoughtfully. “More as a command, if you get my meaning.”

“You imagine that you can bend a lens-artist to your will and make him false to his professional reputation?”

“I was thinking of having a try.”

“Do you realize that, if my incarceration here were known, ten thousand photographers would tear this house brick from brick and you limb from limb?”

“But it isn’t,” the Mayor pointed out. “And that, if you follow me, is the whole point. You came here by night in a closed car. You could stay here for the rest of your life, and no one would be any the wiser. I really think you had better reconsider, Mr. Mulliner.”

“You have had my answer.”

“Well, I’ll leave you to think it over. Dinner will be served at seven-thirty. Don’t bother to dress.”

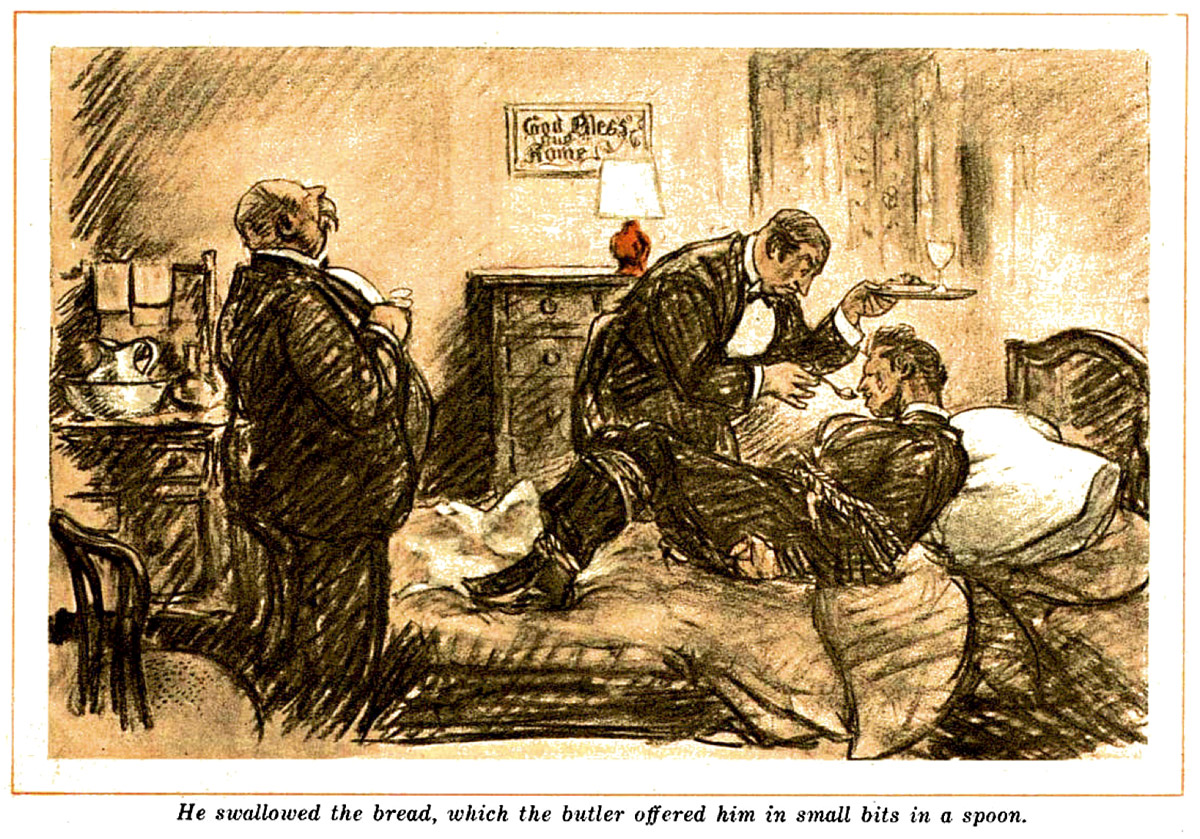

AT half-past seven precisely the door opened again, and the Mayor reappeared, followed by a butler bearing on a silver salver a glass of water and a small slice of bread. Pride urged Clarence to reject the refreshment, but hunger overcame pride. He swallowed the bread, which the butler offered him in small bits in a spoon, and drank the water.

“At what hour would the gentleman desire breakfast, sir?” asked the butler.

“Now,” said Clarence, for his appetite, always healthy, seemed to have been sharpened.

“Let us say nine o’clock,” suggested the Mayor. “Put aside another slice of that bread, Meadowes. And no doubt Mr. Mulliner would enjoy a glass of this excellent water.”

For perhaps half an hour after his host had left him, Clarence’s mind was obsessed to the exclusion of all other thoughts by a vision of the dinner he would have liked to be enjoying. All we Mulliners have been good trenchermen, and to put a bit of bread into it after it had been unoccupied for a whole day was to offer to Clarence’s stomach an insult which it resented with indescribable bitterness. Clarence’s only emotion for some time, then, was that of hunger. His thoughts centered themselves on food. And it was to this fact, oddly enough, that he owed his release.

FOR, as he lay there in a sort of delirium, picturing himself getting outside a medium-cooked steak smothered in onions, with grilled tomatoes and floury potatoes on the side, it was suddenly borne in upon him that this steak did not taste quite so good as other steaks he had eaten in the past. It was tough and lacked juiciness. It tasted just like rope.

And then, his mind clearing, he saw that it actually was rope. Carried away by the anguish of hunger, he had been chewing the cord that bound his hands; and he now discovered that he had bitten into it quite deeply.

A sudden flood of hope poured over Clarence Mulliner. Carrying on at this rate, he perceived, he would be able ere long to free himself. It needed only a little imagination. After a brief interval to rest his aching jaws, he put himself deliberately into that state of relaxation which is recommended by the apostles of Suggestion.

“I am entering the dining-room of my club,” murmured Clarence. “I am sitting down. The waiter is handing me the bill of fare. I have selected roast duck with green peas and new potatoes, lamb cutlets with Brussels sprouts, fricassee of chicken, porterhouse steak, boiled beef and carrots, leg of mutton, haunch of mutton, mutton chops, curried mutton, veal, kidneys sauté, spaghetti Caruso, and eggs and bacon, fried on both sides. The waiter is now bringing my order. I have taken up my knife and fork. I am beginning to eat.”

And, murmuring a brief grace, Clarence flung himself on the rope and set to.

Twenty minutes later he was hobbling about the room, restoring the circulation to his cramped limbs.

Just as he had succeeded in getting himself nicely limbered up, he heard the key turning in the door.

Clarence crouched for the spring. The room was quite dark now, and he was glad of it, for darkness well fitted the work that lay before him. His plans conceived on the spur of the moment were necessarily sketchy, but they included jumping on the Mayor’s shoulders and pulling his head off. After that, no doubt, other modes of self-expression would suggest themselves.

The door opened. Clarence made his leap. And he was just about to start on the program as arranged, when he discovered with a shock of horror that he was being rough with a woman. And no photographer worthy of the name will ever lay a hand upon a woman, save to raise her chin and tilt it a little more to the left.

“I beg your pardon!” he cried.

“Don’t mention it,” said his visitor in a low voice. “I hope I didn’t disturb you.”

“Not at all,” said Clarence.

There was a pause.

“Rotten weather,” said Clarence, feeling that it was for him, as the male member of the sketch, to keep the conversation going.

“Yes, isn’t it?”

“A lot of rain we’ve had this summer.”

“Yes. It seems to get worse every year.”

“Doesn’t it?”

“I hate rain.”

“So do I.”

“Of course, we may have a fine August.”

“Yes, there’s always that.”

THE ice was broken, and the girl seemed to become more at her ease.

“I came to let you out,” she said. “I must apologize for my father. He has always yearned to have me photographed by you, but I cannot consent to allow a photographer to be coerced into abandoning his principles. If you will follow me, I will let you out by the front door.”

“It’s awfully good of you,” said Clarence awkwardly. He was embarrassed. He wished that he could have obliged this kind-hearted girl by taking her picture, but a natural delicacy restrained him from touching on this subject. They went down the stairs in silence.

On the first landing, a hand was placed on his in the darkness and the girl’s voice whispered in his ear.

“We are just outside father’s study,” he heard her say. “We must be as quiet as mice.”

“As what?” said Clarence.

“Mice.”

“Oh, rather,” said Clarence, and immediately bumped into a pedestal of some sort with a vase on top. There was a noise like ten simultaneous dinner services coming apart in the hands of ten simultaneous parlor maids. And then the door was flung open. The landing became flooded with light, and the Mayor of Tooting East stood before them. He was carrying a revolver, and his face was dark with menace.

“Ha!” said the Mayor.

But Clarence was staring open-mouthed at the girl. She had shrunk back against the wall, and the light fell full upon her.

“You!” cried Clarence.

“This—” began the Mayor.

“You! At last!”

“This is a pretty—”

“Am I dreaming?”

“This is a pretty state of af—”

“Ever since that day I saw you in the cab I have been scouring London for you. To think that I have found you at last!”

“This is a pretty state of affairs,” said the Mayor—breathing on the barrel of his revolver and polishing it on the sleeve of his coat—“my daughter helping the foe of her family to fly—”

“Flee, father,” corrected the girl faintly.

“Flee or fly—this is no time for arguing about insects. Let me tell you—”

Clarence interrupted him indignantly.

“What do you mean,” he said, “by telling me that she took after you? She is the loveliest girl in the world, while you look like Lon Chaney made up for something. Your face—if you can call it that—is one of those beastly, blobby, squashy sort of faces—”

“Here!” said the Mayor.

“—whereas hers is simply divine. Your eyes are bulbous and prawnlike—”

“Hey!” said the Mayor.

“—while hers are sweet and soft and intelligent. Your ears—”

“Yes, yes,” said the Mayor petulantly. “Some other time, some other time. Then am I to take it, Mr. Mulliner—”

“Call me Clarence.”

“I refuse to call you Clarence.”

“You will have to very shortly, when I am your son-in-law.”

The girl uttered a cry. The Mayor uttered a louder cry.

“My son-in-law!”

“That,” said Clarence firmly, “is what I intend to be—and speedily.”

He turned to the girl.

“I am a man of volcanic passions, and now that love has come to me there is no power in heaven or earth that can keep me from the object of my love. It will be my never-ceasing task—er—”

“Gladys,” prompted the girl.

“Thank you. It will be my never-ceasing task, Gladys, to strive daily to make you return that love—”

“You need not strive, Clarence,” she whispered softly. “It is already returned.”

Clarence reeled.

“Already?” he gasped.

“I have loved you since I saw you in that cab. When we were torn asunder, I felt quite faint.”

“So did I. I was in a daze. I tipped my cabman at Waterloo three half crowns. I was aflame with love.”

“I can hardly believe it.”

“Nor could I, when I found out. I thought it was threepence. And ever since that day—”

THE Mayor coughed.

“Then am I to take it—er—Clarence,” he said, “that your objections to photographing my daughter are removed?”

Clarence laughed happily.

“Listen,” he said, “and I’ll show you the sort of son-in-law I am. Ruin my professional reputation though it may, I will take a photograph of you too!”

“Me!”

“Absolutely. Standing beside her with the tips of your fingers on her shoulder. And, what’s more, you may wear your cocked hat.”

Tears had begun to trickle down the Mayor’s cheeks.

“My boy!” he sobbed brokenly. “My boy!”

And so happiness came to Clarence Mulliner at last.

He never became President of the Bulb-Squeezers, for he retired from business the next day, declaring that the hand that had snapped the shutter when taking the photograph of his dear wife should never snap it again for sordid profit.

The wedding, which took place some six weeks later, was attended by almost everybody of any note in Society or on the Stage, and was the first occasion on which a bride and bridegroom had ever walked out of church beneath an arch of crossed tripods.

the end

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums