The Century Magazine, Febuary 1915

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough-hew them how we will.

CONSIDER the case of Henry Pifield Rice, detective.

I must explain Henry early, to avoid disappointment. If I simply said he was a detective, and let it go at that, I should be obtaining the reader’s interest under false pretenses. He was really only a sort of detective, a near-sleuth. At Stafford’s International Investigation Bureau, where he was employed, they did not require him to solve mysteries which had baffled the police. He had never measured a footprint in his life, and what he did not know about blood-stains would have filled a library. The sort of job they gave Henry was to stand outside a restaurant in the rain and note what time some one inside left it. In short, it is not “Pifield Rice, Investigator. No. I. The Adventure of the Maharajah’s Ruby,” that I submit to your notice, but the unsensational doings of a commonplace young man, variously known to his comrades at the bureau as “bone-head,” “that chump What’s-his-name,” “Here, you!”

Henry lived at a boarding-house on Fourth Avenue. One day a new girl came to the boarding-house, and sat next to Henry at meals. Her name was Alice Weston. She was small and quiet and rather pretty. They got on splendidly. Their conversation, at first confined to the weather, base-ball, and the moving-pictures, rapidly became more intimate. Henry was surprised to find that she was on the stage, in the chorus. Previous chorus-girls at the boarding-house had been of a more pronounced type; good girls, but noisy, and apt to chew gum. Alice Weston was different.

“I’m rehearsing at present,” she said. “I’m going out on the road next month in ‘The Girl from Broadway.’ What do you do, Mr. Rice?”

Henry paused for a moment before replying. He knew how sensational he was going to be.

“I’m a detective.”

Usually, when he told girls his profession, squeaks of amazed admiration greeted him. Now he was chagrined to perceive distinct disapproval in the brown eyes that met his.

“What’s the matter?” he said a little anxiously, for even at this early stage in their acquaintance he was aware of a strong desire to win her approval. “Don’t you like detectives?”

“I don’t know. Somehow I shouldn’t have thought you were one.” This restored Henry’s equanimity somewhat. Naturally a detective does not want to look like a detective. “I think—you won’t be offended?” she went on after a pause.

“Go on.”

“I’ve always looked on it as rather a sneaky job.”

“Sneaky!” moaned Henry.

“Well, creeping about, spying on people.’’

Henry was appalled. She had defined his own trade to a nicety. There might be detectives whose work was above this reproach, but he was a confirmed creeper, and he knew it. It was not his fault. The boss told him to creep, and he crept. If he declined to creep, he would be fired instanter. It was hard, and yet he felt the sting of her words; and in his bosom the first seeds of dissatisfaction with his occupation took root.

One might have thought that this frankness on the girl’s part would have kept Henry from falling in love with her. Certainly the dignified thing would have been to change his seat at table, and take his meals next to some one who appreciated the romance of detective work a little more. But no, he remained where he was, and presently Cupid, who never shoots with a surer aim than through the steam of boarding-house corned beef, sniped him where he sat.

He proposed to Alice Weston. She refused him.

“It’s not because I’m not fond of you. I think you’re the nicest man I ever met.” A good deal of assiduous attention had enabled Henry to win this place in her affections. He had worked patiently and well before actually putting his fortune to the test. “I’d marry you to-morrow if things were different. But I’m on the stage, and I mean to stick there. Most of the girls are crazy to get off it, but not I. And one thing I’ll never do is to marry some one who isn’t in the profession. My sister Genevieve did, and look what happened to her. She married a traveling-salesman, and, believe me, he traveled. She never saw him for more than five minutes in the year, except when he was selling bath-tubs in the same town where she was doing her refined specialty; and then he’d just wave his hand, and whiz by, and start right in traveling again. My husband has got to be right there where I can see him. I’m sorry, Henry, but I know I’m right.”

It seemed final, but Henry did not wholly despair. He was a resolute young man. One has to be, to wait outside restaurants in the rain for any length of time.

He had an inspiration. He sought out a dramatic agent.

“I want to go on the stage in musical comedy.”

“Let’s see you dance.”

“I can’t dance.”

“Sing!” said the agent. “Stop singing!” he broke in, then added soothingly, “You go away and have a nice cup of hot tea, and you’ll be as right as anything in the morning.”

Henry went away.

A few days later, at the bureau, his fellow-detective Simmonds hailed him.

“Here, you! The boss wants you. Hustle!”

Mr. Stafford was talking into the telephone. He replaced the receiver as Henry entered.

“Oh, Rice, here’s a woman wants her husband shadowed while he’s on the road. He’s an actor. I’m sending you. Beat it up to this address, and get photographs and all particulars. You’ll have to make the eleven o’clock train on Friday.”

“Yes, sir.”

“He’s in ‘The Girl from Broadway’ company. They open at Syracuse.”

It sometimes seemed to Henry as if Fate did it on purpose. If the commission had had to do with any other company, it would have been well enough, for, professionally speaking, it was the most important with which he had ever been intrusted. If he had never met Alice Weston, and heard her views upon detective work, he would have been pleased and flattered. Things being as they were, it was Henry’s considered opinion that Fate had slipped one over on him.

In the first place, what torture to be always near her, unable to reveal himself; to watch her while she disported herself in the company of other men! He would be disguised, and she would not recognize him; but he would recognize her, and his sufferings would be dreadful. In the second place, to have to do his creeping about and spying virtually in her presence! Still, business was business.

At five minutes to eleven on the morning named he was at the station, a false beard and spectacles shielding his identity from the public eye. If you had asked him, he would have said that he was a German business man. As a matter of fact, he looked far more like an automobile coming through a haystack.

The platform was crowded. Friends of the company had come to see the company off. Henry looked on discreetly from behind a negro porter, whose bulk formed a capital screen. He recognized celebrities. The fat man in the brown suit was Walter Jelliffe, the comedian and star of the company. Henry stared keenly at him through the spectacles.

He saw Alice. She was talking to a man with a face like a hatchet, and smiling, too, as if she enjoyed it. Behind the matted foliage which he had inflicted on his face Henry’s teeth came together with a snap.

In the weeks that followed, as he dogged “The Girl from Broadway” company from town to town, it would be difficult to say whether Henry was happy or unhappy. On the one hand, to realize that Alice was so near and yet so inaccessible was a constant source of misery; yet, on the other, he could not but admit that he was enjoying the life.

He was made for it, he considered. Fate had placed him in an office in New York, but what he really enjoyed was this unfettered travel. Some Gipsy strain in him rendered even the obvious discomforts of theatrical touring agreeable. He liked catching trains; he liked invading strange hotels; above all, he reveled in the artistic pleasure of watching unsuspected fellow-men as if they were so many ants.

That was really the best part of the whole thing. It was all very well for Alice to talk about creeping and spying, but, if you considered it without bias, there was nothing degrading about it at all. It was an art. It took brains and a genius for disguise to make a man a successful creeper and spier. You couldn’t simply say to yourself, “I will creep.” If you attempted to do it in your own person, you would be detected instantly. You had to be an adept at masking your personality. You had to be one man at Syracuse and another at Buffalo, especially if, like Henry, you were of a gregarious disposition, and liked the society of actors.

The stage had always fascinated Henry. To meet even minor members of the profession off the boards gave him a thrill. There was a resting juvenile, of one-night-stand caliber, at his boarding-house who could always get half a dollar out of him simply by talking about how he had jumped in and saved the show at various hamlets that he had visited in the course of his wanderings. And on this “Girl from Broadway” tour he was in constant touch with men who really amounted to something. Walter Jelliffe had been a celebrity when Henry was attending school, and Sidney Crane, the baritone, and others of the lengthy cast were all players not unknown in New York. Henry courted them assiduously.

It had not been hard to scrape acquaintance with them. The principals of the company always put up at the best hotel, and, his expenses being paid by his employer, so did Henry. It was the easiest thing possible to bridge with a well-timed cocktail the gulf between non-acquaintance and warm friendship. Walter Jelliffe in particular was peculiarly accessible. Every time Henry accosted him—as a different person, of course—and renewed in a fresh disguise the friendship which he had enjoyed at the last town, Walter Jelliffe met him more than halfway.

It was in the sixth week of the tour that the comedian, promoting him from casual acquaintanceship, invited him to come up to his room and smoke a cigar. Henry was pleased and flattered. Jelliffe was a personage, always surrounded by admirers, and the compliment was consequently of a high order.

He lit his cigar. Among his friends at the Lambs’ Club it was unanimously held that Walter Jelliffe’s cigars brought him within the scope of the Sullivan Law: but Henry would have smoked the gift of such a man if it had been a cabbage-leaf. He puffed away contentedly. He was made up as an old Southern colonel that week, and he complimented his host on the aroma with a fine Old-World courtesy.

Walter Jelliffe seemed gratified.

“Quite comfortable?” he asked.

“Quite, I thank you, suh,” said Henry, fondling his silver beard.

“That’s right. And now tell me, old man, which of us is it you’re trailing?”

Henry nearly swallowed his cigar.

“What do you mean—suh?”

“Oh, come,” protested Jelliffe, “there’s no need to keep it up with me. I know you’re a detective, and you’re here because somebody’s wife has sicked you on. I’ve had it happen before. The question is, Who’s the man? That’s what we’re all been wondering all this time.”

All—they had all been wondering! It was worse than Henry could have imagined. Till now he had pictured his position with regard to “The Girl from Broadway” company as that of some scientist who, seeing, but unseen, keeps a watchful eye on the denizens of a drop of water under his microscope. And they had all detected him—every one of them.

It was a stunning blow. If there was one thing on which Henry prided himself, it was the impenetrability of his disguises. He might be slow, he might be on the stupid side; but, he contended, he could disguise himself. He had a variety of disguises, each designed to befog the public more hopelessly than the last.

Henry did not know it, but he had achieved in the eyes of the Afro-American lady who answered the front-door bell at his boarding-house a well-established reputation as a humorist of the more practical kind. It was his habit to try out his disguises on her. He would ring the bell, inquire for the landlady, and, when Lottie had gone, leap up the stairs to his room. Here he would remove the disguise, resume his normal appearance, and come down-stairs again, humming a careless air. Lottie, meanwhile, in the kitchen, would be confiding to her ally, the cook, that Mistuh Rice had jest came in, lookin’ kind o’ funny again.

He sat and gaped at Walter Jelliffe. The comedian regarded him curiously.

“You look at least a hundred years old,” he said. “What are you made up as? A piece of cheese?”

Henry glanced hastily at the mirror. Yes, he did look rather old. He must have overdone some of the lines on his forehead. He looked something between a youngish centenarian and a nonagenarian who had seen a good deal of trouble.

“If you knew how you were demoralizing the company,” Jelliffe went on, “you would have a heart and quit. As nice and quiet a lot of boys as ever you met till you came along. Now they do nothing but bet on what disguise you’re going to choose for the next town. I don’t see why you need to change so often. You were all right as the German in Syracuse. We were all saying how cute you looked. You should have stuck to that. But what do you do at Buffalo but roll in in a scrubby mustache and a sack-coat, looking rotten. However, all that is beside the point. It’s a free country. If you like to spoil your beauty, I guess there’s no law against it. What I want to know is, Who’s the man? Whose track are you sniffing on, Bill? You’ll pardon my calling you Bill. You’re known as ‘Bill, the Bloodhound,’ in the company. Who’s the man?”

“Never mind,” said Henry.

He was aware, as he made it, that it was not a very able retort, but he was feeling too limp for satisfactory repartee. Criticisms in the bureau, dealing with his alleged solidity of skull, he did not resent. He attributed them to man’s natural desire to josh his fellow-man. But to be unmasked by the general public in this way was another matter. It struck at the root of all things.

“But I do mind,” objected Jelliffe. “It’s most important. A wad of money hangs on it. We’ve got a sweepstake on in the company, the holder of the winning name to draw down the entire receipts. Come on; slip us the info’.”

Henry rose, and made for the door. His feelings were too deep for words. Even a minor detective has his professional pride, and the knowledge that his espionage is being made the basis of sweepstakes by his quarry cuts this to the quick.

“Here, don’t go! Where are you going?”

“Back to New York,” said Henry, bitterly. “It’s a lot of good, my trailing along now, isn’t it!”

“You bet it is—to me. Don’t be in a hurry. Stop, look, and listen. You’re thinking that, now we are on to you, your utility as a sleuth has waned to some extent—is that it?”

“Well?”

“Well, you shouldn’t get perturbed. What does it matter to you? You don’t get paid by results, do you? Your boss said, ‘Tag along.’ Well, do it, then. I should hate to lose you. I don’t suppose you know it, but you’ve been the best mascot on this tour that I’ve ever come across. Right from the start we’ve been playing to enormous business. I’d rather kill a black cat than lose you. Cut out the disguises, and stick along with us. Come behind all you want, and be sociable.”

A detective is only human. The less a detective, the more human he is. Henry was not much of a detective, and his human traits were consequently highly developed. From boyhood he had never been able to resist curiosity. If a crowd collected in the street, he always added himself to it; and he would have stopped to gape at a window with “Watch This Window” written on it if he had been running for his life from wild bulls. He was, and always had been, intensely desirous of some day penetrating behind the scenes of a theater.

And there was another thing. At last, if he accepted this invitation, he would be able to see and speak to Alice Weston, and interfere with the manœuvers of the hatchet-faced man, on whom he had brooded with suspicion and jealousy since that first morning at the station. To see Alice! Perhaps, with eloquence, to talk her out of that ridiculous resolve of hers.

“Why, there’s something in that,” he said.

“You bet there is. Well, that’s settled. And now, touching that sweep, who is it?”

“I can’t tell you that. You see, as far as that goes, I’m just where I was before. I can still watch, whoever it is I’m watching.”

“Darn it! so you can. I didn’t think of that,” said Jelliffe, who possessed a sensitive conscience. “Purely between ourselves, it isn’t me, is it?”

Henry eyed him inscrutably. He could look inscrutable at times.

“Ah!” he said, and left quickly, with the feeling that, however poorly he had shown up during the actual interview, his exit had been good. He might have been a failure in the matter of disguise, but Sherlock Holmes could not have put more quiet sinisterness into that “Ah!” It did much to soothe him and insure a peaceful night’s rest.

Henry, as a consequence, was the center of a kaleidoscopic whirl of feminine loveliness, dressed to represent such varying flora and fauna as rabbits, Parisian students, piccaninnies, Dutch peasants, and daffodils. Musical comedy is the Irish stew of the drama. Anything may be put into it, with the certainty that it will improve the general effect.

He scanned the throng for a sight of Alice. Often as he had seen the piece in the course of its six-weeks’ wandering in the wilderness, he had never succeeded in recognizing her from the front of the house. Quite possibly, he thought, she might be on the stage already, hidden in a rose-tree or some other shrub, ready at the signal to burst forth in short skirts upon the audience; for in “The Girl from Broadway” almost anything could turn suddenly into a chorus-girl.

Then he saw her among the daffodils. She was not a particularly convincing daffodil, but she looked good to Henry. With wabbling knees he butted his way through the crowd, and seized her hand enthusiastically.

“Why, Henry! Where did you come from?”

“I am glad to see you.”

“How did you get here?”

“Say, I am glad to see you!”

At this point the stage-manager, bellowing from the prompt-box, urged Henry to check it with his hat. It is one of the mysteries of behind-the-scenes acoustics that a whisper from any minor member of the company can be heard all over the house, while the stage-manager can burst himself without annoying the audience.

Henry, awed by authority, relapsed into silence. From the unseen stage came the sound of some one singing a song about the moon. June was also mentioned. He recognized the song as one that had always bored him. He disliked the woman who was singing it, a Miss Clarice Weaver, who played the heroine of the piece to Sidney Crane’s hero.

In this opinion he was not alone. Miss Weaver was not popular in the company. She had secured the rôle rather as a testimony of personal esteem from the management than because of any innate ability. She sang badly, acted indifferently, and was uncertain what to do with her hands. All these things might have been forgiven her, but she supplemented them by the crime known in stage circles as “throwing her weight about.” That is to say, she was hard to please, and, when not pleased, apt to say so in no uncertain voice. To his personal friends Walter Jelliffe had frequently confided that, though not wealthy, he was in the market with a substantial reward for any one who was man enough to drop a ton of iron on Miss Weaver.

To-night the song annoyed Henry more than usual, for he knew that very soon the daffodils were due on the stage to clinch the verisimilitude of the scene by dancing a fox-trot with the rabbits. He tried to make the most of the time at his disposal.

“I am glad to see you,” he said.

“ ’Sh!” said the stage-manager.

Henry was discouraged. Romeo could not have made love under these conditions. He wandered moodily off into the dusty semi-darkness. He avoided the prompt-corner, whence he could have caught a glimpse of Alice, being loath to meet the stage-manager just at present.

Walter Jelliffe came up to him as he sat on a box and brooded on life.

“A little less of the double forte, old man,” he said. “Miss Weaver has been kicking about the noise on the side. She wanted you thrown out, but I said you were my mascot, and I would die sooner than part with you. But I should go easy on the chest-notes, I think, all the same.”

Henry nodded moodily. He was depressed. He had the feeling, which comes easily to the intruder behind the scenes, that nobody loved him.

The drama proceeded. From the front of the house roars of laughter indicated the presence on the stage of Walter Jelliffe, while now and then a lethargic silence suggested that Miss Clarice Weaver was in action. From time to time the empty space about him filled with girls dressed in accordance with the exuberant fancy of the producer of the piece. When this happened, Henry would leap from his seat and endeavor to locate Alice; but always, just as he thought he had done so, the hidden orchestra would burst into melody and the chorus would be called to the front.

It was not till late in the second act that he found an opportunity for further speech.

The plot of “The Girl from Broadway” had by then reached a critical stage. The situation was as follows: the hero, having been disinherited by his millionaire father for falling in love with the heroine, a poor shop-girl, has disguised himself (by wearing a different colored necktie), and has come in pursuit of her to a well-known seaside resort, where, having disguised herself by changing her dress, she is serving in a shop on the board-walk. The family butler, disguised as a frankfurter-seller, has followed the hero; and the millionaire father, disguised as an Italian opera-singer, has come to the place in search of a receipt for the manufacture of pickled walnuts, which a dying inventor has bequeathed to him. They all meet on the board-walk. Each recognizes the other, but thinks he himself is unrecognized. All disappear hurriedly, leaving the heroine alone on the stage.

It is a crisis in her life. She meets it bravely: she sings a song entitled “My Honolulu Queen,” with chorus of Japanese girls and Bulgarian officers.

Alice was one of the Japanese girls. She was standing a little apart from the other Japanese girls. Henry hurried to her side. Now was his time. He felt keyed up, full of persuasive words. In the interval which had elapsed since their last conversation, yeasty emotions had been playing the dickens with his self-control. It is virtually impossible for a novice, suddenly introduced behind the scenes of a musical comedy, not to fall in love with somebody; and, if he is already in love, his fervor is increased to a dangerous point.

Henry felt that it was now or never. He forgot that it was perfectly possible, indeed, reasonable, to wait till the performance was over and renew on the way back to her hotel his appeal to Alice to marry him. He had the feeling that he had just about a quarter of a minute. Quick action was Henry’s slogan.

He seized her hand.

“Alice!”

“ ’Sh!” hissed the stage-manager.

“Listen! I love you. I’m crazy about you. What does it matter whether I’m on the stage or not? I love you.”

“Can that forcibly qualified row there!”

“Won’t you marry me?”

She looked at him. It seemed to him that she hesitated.

“Cut it out!” bellowed the stage-manager, and Henry cut it out.

At that moment, when his whole fate hung in the balance, there came from the stage that devastating high note which was the sign that the solo was over and that the chorus was about to mobilize. As if drawn by some magnetic power, she suddenly receded from him, and went out to the stage.

A man in Henry’s position and frame of mind is not responsible for his actions. He saw nothing but her; he was blind to the fact that important manœuvers were in progress; all he understood was that she was going from him, and that he must stop her and get this thing settled.

He clutched at her. She was out of range, and getting farther away every instant.

He sprang forward.

The advice that should be given to every young man starting life is, if he happens to be behind the scenes at a theater, never to spring forward. The whole architecture of the place is designed to undo those who spring. Hours before the stage carpenters have laid their traps, and in the semi-darkness one cannot but fall into them.

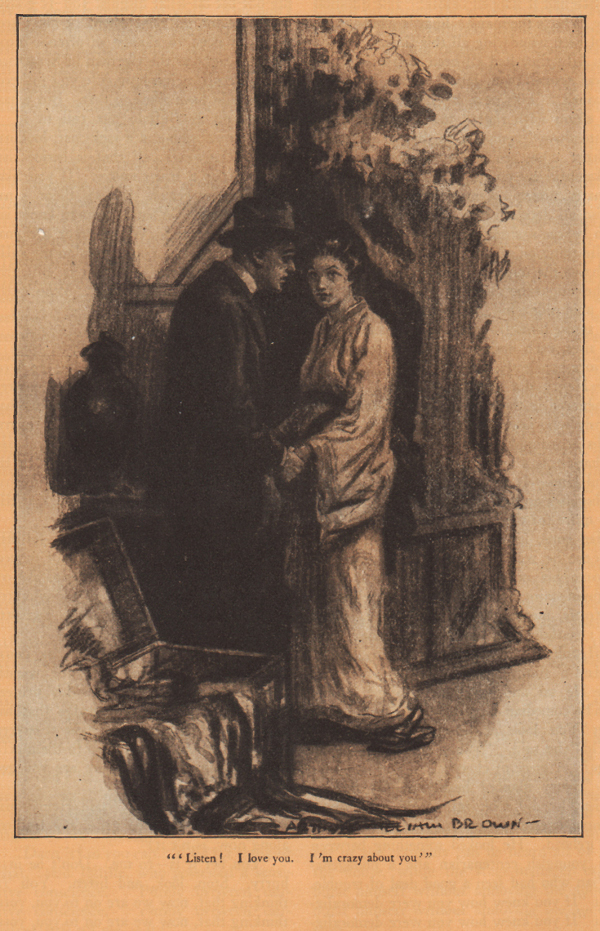

The trap into which Henry fell was a raised board. It was not a very highly raised board. Stubbing it squarely with his toe, Henry shot forward, all arms and legs.

It is the instinct of man, in such a situation, to grasp at the nearest support. Henry caught at the Hotel Superba, the pride of the board-walk. It was a thin wooden edifice, and it supported him for perhaps a tenth of a second. Then he staggered with it into the spotlight, tripped over a Bulgarian officer who was inflating himself for a deep note, and finally fell in a complicated heap as exactly in the center of the stage as if he had been a star of years’ standing.

It went well. There was no question of that. Previous audiences had always been rather cold toward this particular song, but this one got on its feet and yelled for more. From all over the house came rapturous demands that Henry go back and do it again.

But Henry was giving no encores. A little stunned, he rose to his feet, and automatically began to dust his clothes. The orchestra, unnerved by this unrehearsed infusion of new business, had stopped playing. Bulgarian officers and Japanese girls alike seemed unequal to the situation. They stood about, waiting for the next thing to break loose. From somewhere far away came faintly the voice of the stage-manager inventing new words, new combinations of words, and new throat noises.

Then Henry, massaging a stricken elbow, was aware of Miss Weaver at his side. Looking up, he caught Miss Weaver’s eye.

A familiar stage-direction of melodrama reads, “Exit cautious through gap in hedge.” It was Henry’s first appearance on any stage, but he did it like a veteran.

“My dear fellow,” said Walter Jelliffe, “don’t apologize.” The hour was midnight, and he was sitting in Henry’s bedroom at the hotel. Leaving the theater, Henry had gone to bed almost instinctively. Bed seemed the only haven for him. “You have put me under lasting obligations,” Jelliffe continued. “In the first place, with your unerring sense of the stage, you saw just the spot where the piece needed livening up, and you livened it up. That was good; but far better was it that you also sent our Miss Weaver into violent hysterics, from which she emerged to hand in her notice. She leaves us to-morrow.”

Henry was appalled at the extent of the disaster for which he was responsible.

“What will you do?”

“Do? Why, it’s what we have all been praying for—a miracle that would eject Miss Weaver. It needed a genius like you to come and put it across. Sidney Crane’s wife can play the part without rehearsal. She understudied it all last season on Broadway. Crane has just been speaking to her on the long distance, and she is making the first train to-morrow.”

Henry sat up in bed.

“What!” he exclaimed.

“What’s the trouble now?” asked Jelliffe.

“Sidney Crane’s wife?”

“What about her?”

A bleakness fell upon Henry’s soul.

“She was the woman who was employing me. Now I shall be taken off the job, and have to go back to New York.”

“You don’t mean that it was really Crane’s wife—”

Jelliffe was regarding him with a kind of awe.

“Laddie,” he said in a hushed voice, “you almost scare me. There seems to be no limit to your powers as a mascot. You fill the house every night, you get rid of the Weaver woman, and now you tell me this. I drew Crane in the sweep, and I would have taken five cents for my chance of pulling down the dough.”

“I shall get a telegram from the boss to-morrow, recalling me.”

“Don’t go. Stick with me. Join the troupe.”

Henry stared.

“What do you mean? I can’t sing or act.”

Jelliffe’s voice thrilled with earnestness.

“My boy, I can go down Broadway and pick up a hundred fellows who can sing and act. I don’t want them; I turn them away. But a seventh son of a seventh son like you, a human horseshoe like you, a king of mascots like you, they don’t make them nowadays. They’ve lost the pattern. If you like to come with me, I’ll give you a life contract. I need you in my business.” He rose. “Think it over, laddie, and let me know to-morrow. Look here upon this picture, and on that. As a sleuth, you are poor. You couldn’t detect the cherry at the bottom of a cocktail glass. You have no future. You are merely among those present. But as a mascot, my boy, you’re the only thing in sight. You can’t help succeeding on the stage. You don’t have to know how to act. Look at the dozens of good actors who are playing tank-towns. Why? Unlucky. No other reason. With your rabbit’s foot and a little experience, you’ll be a star before you know you’ve begun. Think it over, and let me know in the morning.”

Before Henry’s eyes there rose a sudden vision of Alice—Alice no longer unattainable, Alice walking on his arm down the aisle, Alice mending his socks, Alice with her heavenly hands fingering his salary envelop.

“Don’t go,” he said. “Don’t go. I’ll let you know now.”

The scene is Broadway, hard by Fortieth Street; the time that restful hour of the afternoon when they of the gnarled faces and the bright clothing gather together in groups to tell one another how good they are. A voice is heard:

“Sure, K—— and E—— keep right on trying to get me, but I turn them down every time. ‘Nix,’ I said to Joe Brooks only yesterday; ‘nothing doing, Joe. I’m going with old Wally Jelliffe, same as usual, and there isn’t the money in the Sub-Treasury that’ll get me away.’ Joe got all worked up. He—”

It is the voice of H. Pifield Rice, actor.

Note: Thanks to Neil Midkiff for providing the transcription and images for this story.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums