The Strand Magazine, December 1920

IN the smoking-room of the club-house a cheerful fire was burning, and the Oldest Member glanced from time to time out of the window into the gathering dusk. Snow was falling lightly on the links. From where he sat, the Oldest Member had a good view of the ninth green; and presently, out of the greyness of the December evening, there appeared over the brow of the hill a golf-ball. It trickled across the green, and stopped within a yard of the hole. The Oldest Member nodded approvingly. A good approach-shot.

A young man in a tweed suit clambered on to the green, holed out with easy confidence, and, shouldering his bag, made his way to the club-house. A few moments later he entered the smoking-room, and uttered an exclamation of rapture at the sight of the fire.

“I’m frozen stiff!”

He rang for a waiter and ordered a hot drink. The Oldest Member gave a gracious assent to the suggestion that he should join him.

“I like playing in winter,” said the young man. “You get the course to yourself, for the world is full of slackers who only turn out when the weather suits them. I cannot understand where they get the nerve to call themselves golfers.”

“Not everyone is as keen as you are, my boy,” said the Sage, dipping gratefully into his hot drink. “If they were, the world would be a better place, and we should hear less of all this modern unrest.”

“I am pretty keen,” admitted the young man.

“I have only encountered one man whom I could describe as keener. I allude to Mortimer Sturgis.”

“The fellow who took up golf at thirty-eight and let the girl he was engaged to marry go off with someone else because he hadn’t the time to combine golf with courtship? I remember. You were telling me about him the other day.”

“There is a sequel to that story, if you would care to hear it,” said the Oldest Member.

“You have the honour,” said the young man. “Go ahead!”

Some people (began the Oldest Member) considered that Mortimer Sturgis was too wrapped up in golf, and blamed him for it. I could never see eye to eye with them. In the days of King Arthur nobody thought the worse of a young knight if he suspended all his social and business engagements in favour of a search for the Holy Grail. In the Middle Ages a man could devote his whole life to the Crusades, and the public fawned upon him. Why, then, blame the man of to-day for a zealous attention to the modern equivalent, the Quest of Scratch? Mortimer Sturgis never became a scratch player, but he did eventually get his handicap down to nine, and I honour him for it.

The story which I am about to tell begins in what might be called the middle period of Sturgis’s career. He had reached the stage when his handicap was a wobbly twelve; and, as you are no doubt aware, it is then that a man really begins to golf in the true sense of the word. Mortimer’s fondness for the game until then had been merely tepid compared with what it now became. He had played a little before, but now he really buckled to and got down to it. It was at this point, too, that he began once more to entertain thoughts of marriage. A profound statistician in this one department, he had discovered that practically all the finest exponents of the art are married men; and the thought that there might be something in the holy state which improved a man’s game, and that he was missing a good thing, troubled him a great deal. Moreover, the paternal instinct had awakened in him. As he justly pointed out, whether marriage improved your game or not, it was to Old Tom Morris’s marriage that the existence of young Tommy Morris, winner of the British Open Championship four times in succession, could be directly traced. In fact, at the age of forty-two, Mortimer Sturgis was in just the frame of mind to take some nice girl aside and ask her to become a step-mother to his eleven drivers, his baffy, his twenty-eight putters, and the rest of the ninety-four clubs which he had accumulated in the course of his golfing career. The sole stipulation, of course, which he made when dreaming his day-dreams was that the future Mrs. Sturgis must be a golfer. I can still recall the horror in his face when one girl, admirable in other respects, said that she had never heard of Harry Vardon, and didn’t he mean Dolly Varden? She has since proved an excellent wife and mother, but Mortimer Sturgis never spoke to her again.

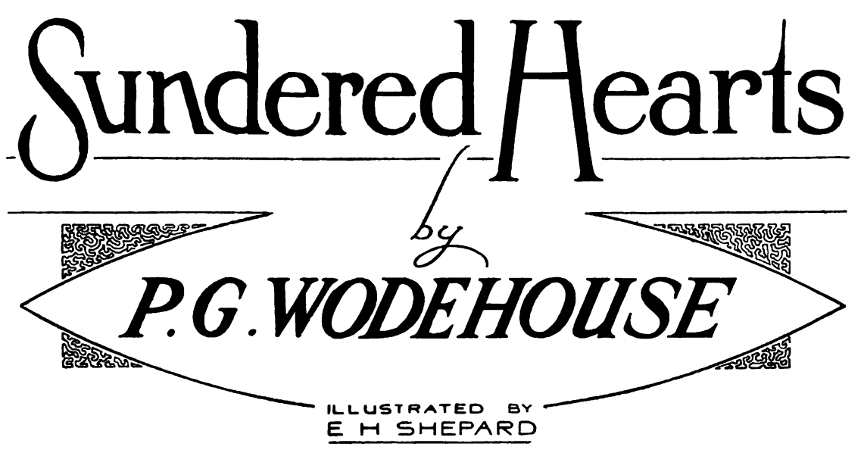

With the coming of January, it was Mortimer’s practice

to leave England and go to the South of France, where there was sunshine

and crisp dry turf. He pursued his usual custom this year. With his suit-case

and his ninety-four clubs he went off to Saint Brule, staying as he always

did at the Hotel Superbe, where they knew him, and treated with an amiable

tolerance his habit of practising chip-shots in his bedroom. On the first

evening, after breaking a statuette of the Infant Samuel in Prayer, he

dressed and went down to dinner. And the first thing he saw was Her.

With the coming of January, it was Mortimer’s practice

to leave England and go to the South of France, where there was sunshine

and crisp dry turf. He pursued his usual custom this year. With his suit-case

and his ninety-four clubs he went off to Saint Brule, staying as he always

did at the Hotel Superbe, where they knew him, and treated with an amiable

tolerance his habit of practising chip-shots in his bedroom. On the first

evening, after breaking a statuette of the Infant Samuel in Prayer, he

dressed and went down to dinner. And the first thing he saw was Her.

Mortimer Sturgis, as you know, had been engaged before, but Betty Weston had never inspired the tumultuous rush of emotion which the mere sight of this girl had set loose in him. He told me later that just to watch her holing out her soup gave him the sort of feeling you get when your drive collides with a rock in the middle of a tangle of rough and kicks back into the middle of the fairway. If golf had come late in life to Mortimer Sturgis, love came later still, and just as the golf, attacking him in the middle life, had been some golf, so was the love considerable love. Mortimer finished his dinner in a trance, which is the best way to do it at some hotels, and then scoured the place for someone who would introduce him. He found such a person eventually and the meeting took place.

SHE was a small and rather fragile-looking girl, with big blue eyes and a cloud of golden hair. She had a sweet expression, and her left wrist was in a sling. She looked up at Mortimer as if she had at last found something that amounted to something. I am inclined to think it was a case of love at first sight on both sides.

“Fine weather we’re having,” said Mortimer, who was a capital conversationalist.

“Yes,” said the girl.

“I like fine weather.”

“So do I.”

“There’s something about fine weather!”

“Yes.”

“It’s—it’s—well, fine weather’s so much finer than weather that isn’t fine,” said Mortimer.

He looked at the girl a little anxiously, fearing he might be taking her out of her depth, but she seemed to have followed his train of thought perfectly.

“Yes, isn’t it?” she said. “It’s so—so fine.”

“That’s just what I meant,” said Mortimer. “So fine. You’ve just hit it.”

He was charmed. The combination of beauty with intelligence is so rare.

“I see you’ve hurt your wrist,” he went on, pointing to the sling.

“Yes. I strained it a little playing in the championship.”

“The championship?” Mortimer was interested. “It’s awfully rude of me,” he said, apologetically, “but I didn’t catch your name just now.”

“My name is Somerset.”

Mortimer had been bending forward solicitously. He overbalanced and nearly fell off his chair. The shock had been stunning. Even before he had met and spoken to her, he had told himself that he loved this girl with the stored-up love of a lifetime. And she was Mary Somerset! The hotel lobby danced before Mortimer’s eyes.

The name will, of course, be familiar to you. In the early rounds of the Ladies’ Open Golf Championship of that year nobody had paid much attention to Mary Somerset. She had survived her first two matches, but her opponents had been nonentities like herself. And then, in the third round, she had met and defeated the champion. From that point on, her name was on everybody’s lips. She became favourite. And she had justified the public confidence by sailing into the final and winning it easily. And here she was, talking to him like an ordinary person, and, if he could read the message in her eyes, not altogether indifferent to his charms, if you could call them that.

“Golly!” said Mortimer, awed.

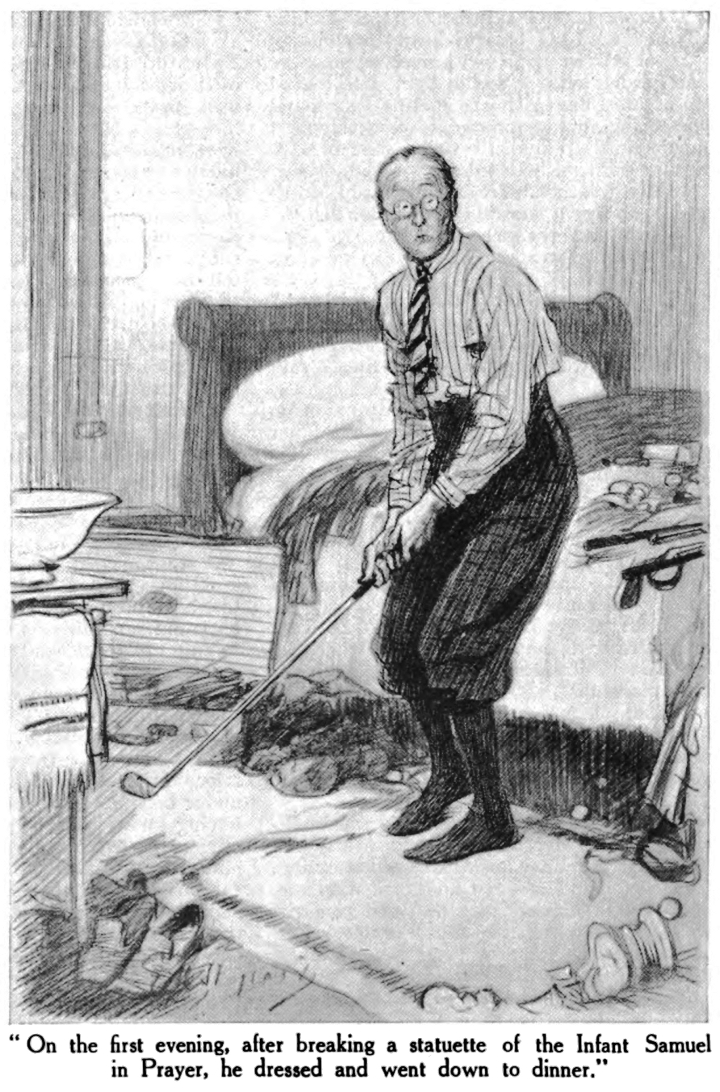

THEIR friendship ripened rapidly, as friendships do in the South of France. In that favoured clime, you find the girl and Nature does the rest. On the second morning of their acquaintance Mortimer invited her to walk round the links with him and watch him play. He did it a little diffidently, for his golf was not of the calibre that would be likely to extort admiration from a champion. On the other hand, one should never let slip the opportunity of acquiring wrinkles on the game, and he thought that Miss Somerset, if she watched one or two of his shots, might tell him just what he ought to do. And sure enough, the opening arrived on the fourth hole, where Mortimer, after a drive which surprised even himself, found his ball in a nasty cuppy lie.

He turned to the girl.

“What ought I to do here?” he asked.

Miss Somerset looked at the ball. She seemed to be weighing the matter in her mind.

“Give it a good hard knock,” she said.

Mortimer knew what she meant. She was advocating a full iron. The only trouble was that, when he tried anything more ambitious than a half-swing, except off the tee, he almost invariably topped. However, he could not fail this wonderful girl, so he swung well back and took a chance. His enterprise was rewarded. The ball flew out of the indentation in the turf as cleanly as though John Henry Taylor had been behind it, and rolled, looking neither to left nor to right, straight for the pin. A few moments later Mortimer Sturgis had holed out one under bogey, and it was only the fear that, having known him for so short a time, she might be startled and refuse him that kept him from proposing then and there. This exhibition of golfing generalship on her part had removed his last doubts. He knew that, if he lived for ever, there could be no other girl in the world for him. With her at his side, what might he not do? He might get his handicap down to six—to three—to scratch—to plus something! Good heavens, why, even the Amateur Championship was not outside the range of possibility. Mortimer Sturgis shook his putter solemnly in the air, and vowed a silent vow that he would win this pearl among women.

Now, when a man feels like that, it is impossible to restrain him long. For a week Mortimer Sturgis’s soul sizzled within him: then he could contain himself no longer. One night, at one of the informal dances at the hotel, he drew the girl out on to the moonlit terrace.

“Miss Somerset——” he began, stuttering with emotion like an imperfectly-corked bottle of ginger-beer. “Miss Somerset—may I call you Mary?”

The girl looked at him with eyes that shone softly in the dim light.

“Mary?” she repeated. “Why, of course, if you like——”

“If I like!” cried Mortimer. “Don’t you know that it is my dearest wish? Don’t you know that I would rather be permitted to call you Mary than do the first hole at Muirfield in two? Oh, Mary, how I have longed for this moment! I love you! I love you! Ever since I met you I have known that you were the one girl in this vast world whom I would die to win! Mary, will you be mine? Shall we go round together? Will you fix up a match with me on the links of life which shall end only when the Grim Reaper lays us both a stymie?”

She drooped towards him.

“Mortimer!” she murmured.

He held out his arms, then drew back. His face had grown suddenly tense, and there were lines of pain about his mouth.

“Wait!” he said, in a strained voice. “Mary, I love you dearly, and because I love you so dearly I cannot let you trust your sweet life to me blindly. I have a confession to make. I am not—I have not always been”—he paused—“a good man,” he said, in a low voice.

She started indignantly.

“How can you say that? You are the best, the kindest, the bravest man I have ever met! Who but a good man would have risked his life to save me from drowning?”

“Drowning?” Mortimer’s voice seemed perplexed. “You? What do you mean?”

“Have you forgotten the time when I fell in the sea last week, and you jumped in with all your clothes on——”

“Of course, yes,” said Mortimer. “I remember now. It was the day I did the long seventh in five. I got off a good tee-shot straight down the fairway, took a baffy for my second, and—— But that is not the point. It is sweet and generous of you to think so highly of what was the merest commonplace act of ordinary politeness, but I must repeat that, judged by the standards of your snowy purity, I am not a good man. I do not come to you clean and spotless as a young girl should expect her husband to come to her. Once, playing in a foursome, my ball fell in some long grass. Nobody was near me. We had no caddies, and the others were on the fairway. God knows——” His voice shook. “God knows I struggled against the temptation. But I fell. I kicked the ball on to a little bare mound, from which it was an easy task with a nice half-mashie to reach the green for a snappy seven. Mary, there have been times when, going round by myself, I have allowed myself ten-foot putts on three holes in succession, simply in order to be able to say I had done the course in under a hundred. Ah! you shrink from me! You are disgusted!”

“I’m not disgusted! And I don’t shrink! I only shivered because it is rather cold.”

“Then you can love me in spite of my past?”

“Mortimer!”

She fell into his arms.

“My dearest,” he said, presently, “what a happy life ours will be. That is, if you do not find that you have made a mistake.”

“A mistake!” she cried, scornfully.

“Well, my handicap is twelve, you know, and not so darned twelve at that. There are days when I play my second from the fairway of the next hole but one, days when I couldn’t putt into a coal-hole with ‘Welcome!’ written over it. And you are a Ladies’ Open Champion. Still, if you think it’s all right—— Oh, Mary, you little know how I have dreamed of some day marrying a really first-class golfer! Yes, that was my vision—of walking up the aisle with some sweet plus two girl on my arm. You shivered again. You are catching cold.”

“It is a little cold,” said the girl. She spoke in a small voice.

“Let me take you in, sweetheart,” said Mortimer. “I’ll just put you in a comfortable chair with a nice cup of coffee, and then I think I really must come out again and tramp about and think how perfectly splendid everything is.”

THEY were married a few weeks later, very quietly, in the little village church of Saint Brüle. The secretary of the local golf-club acted as best man for Mortimer, and a girl from the hotel was the only bridesmaid. The whole business was rather a disappointment to Mortimer, who had planned out a somewhat florid ceremony at St. George’s, Hanover Square, with the Vicar of Tooting (a scratch player, excellent at short approach shots) officiating, and “The Voice That Breathed O’er St. Andrews” booming from the organ. He had even had the idea of copying the military wedding and escorting his bride out of the church under an arch of crossed cleeks. But she would have none of this pomp. She insisted on a quiet wedding, and for the honeymoon trip preferred a tour through Italy. Mortimer, who had wanted to go to Scotland to visit the birthplace of James Braid, yielded amiably, for he loved her dearly. But he did not think much of Italy. In Rome, the great monuments of the past left him cold. Of the Temple of Vespasian, all he thought was that it would be a devil of a place to be bunkered behind. The Colosseum aroused a faint spark of interest in him, as he speculated whether Abe Mitchell would use a full brassey to carry it. In Florence, the view over the Tuscan Hills from the Torre Rosa, Fiesole, over which his bride waxed enthusiastic, seemed to him merely a nasty bit of rough which would take a deal of getting out of.

And so, in the fullness of time, they came home to Mortimer’s cosy little house adjoining the links.

MORTIMER was so busy polishing his ninety-four clubs on the evening of their arrival that he failed to notice that his wife was preoccupied. A less busy man would have perceived at a glance that she was distinctly nervous. She started at sudden noises, and once, when he tried the newest of his mashie-niblicks and broke one of the drawing-room windows, she screamed sharply. In short, her manner was strange, and, if Edgar Allan Poe had put her into “The Fall Of The House Of Usher,” she would have fitted it like the paper on the wall. She had the air of one waiting tensely for the approach of some imminent doom. Mortimer, humming gaily to himself as he sand-papered the blade of his twenty-second putter, observed nothing of this. He was thinking of the morrow’s play.

“Your wrist’s quite well again now, darling, isn’t it?” he said.

“Yes. Yes, quite well.”

“Fine!” said Mortimer. “We’ll breakfast early—say at half-past seven—and then we’ll be able to get in a couple of rounds before lunch. A couple more in the afternoon will about see us through. One doesn’t want to over-golf oneself the first day.” He swung the putter joyfully. “How had we better play, do you think? We might start with you giving me a half.”

She did not speak. She was very pale. She clutched the arm of her chair tightly till the knuckles showed white under the skin.

To anybody but Mortimer her nervousness would have been even more obvious on the following morning, as they reached the first tee. Her eyes were dull and heavy, and she started when a grasshopper chirruped. But Mortimer was too occupied with thinking how jolly it was having the course to themselves to notice anything.

He scooped some sand out of the box, and took a ball out of her bag. His wedding-present to her had been a brand-new golf-bag, six dozen balls, and a full set of the most expensive clubs, all born in Scotland.

“Do you like a high tee?” he asked.

“Oh, no,” she replied, coming with a start out of her thoughts. “Doctors say it’s indigestible.”

Mortimer laughed merrily.

“Deuced good!” he chuckled. “Is that your own or did you read it in a comic paper? There you are!” He placed the ball on a little hill of sand, and got up. “Now let’s see some of that championship form of yours!”

She burst into tears.

“My darling!”

Mortimer ran to her and put his arms round her. She tried weakly to push him away.

“My angel! What is it?”

She sobbed brokenly. Then, with an effort, she spoke.

“Mortimer, I have deceived you!”

“Deceived me?”

“I have never played golf in my life! I don’t even know how to hold the caddie!”

Mortimer’s heart stood still. This sounded like the gibberings of an unbalanced mind, and no man likes his wife to begin gibbering immediately after the honeymoon.

“My precious! You are not yourself!”

“I am! That’s the whole trouble! I’m myself and not the girl you thought I was!”

Mortimer stared at her, puzzled. He was thinking that it was a little difficult and that, to work it out properly, he would need a pencil and a bit of paper.

“My name is not Mary!”

“But you said it was.”

“I didn’t. You asked if you could call me Mary, and I said you might, because I loved you too much to deny your smallest whim. I was going on to say that it wasn’t my name, but you interrupted me.”

“Not Mary!” The horrid truth was coming home to Mortimer. “You were not Mary Somerset?

“Mary is my cousin. My name is Mabel.”

“But you said you had sprained your wrist playing in the championship.”

“So I had. The mallet slipped in my hand.”

“The mallet!” Mortimer clutched at his forehead. “You didn’t say ‘the mallet’?”

“Yes, Mortimer! The mallet!”

A faint blush of shame mantled her cheek, and into her blue eyes there came a look of pain, but she faced him bravely.

“I am the Ladies’ Open Croquet Champion!” she whispered.

Mortimer Sturgis cried aloud, a cry that was like the shriek of some wounded animal.

“Croquet!” He gulped, and stared at her with unseeing eyes. He was no prude, but he had those decent prejudices of which no self-respecting man can wholly rid himself, however broad-minded he may try to be. “Croquet!”

There was a long silence. The light breeze sang in the pines above them. The grasshoppers chirruped at their feet.

She began to speak again, in a low, monotonous voice.

“I blame myself! I should have told you before, while there was yet time for you to withdraw. I should have confessed this to you that night on the terrace in the moonlight. But you swept me off my feet, and I was in your arms before I realized what you would think of me. It was only then that I understood what my supposed skill at golf meant to you, and then it was too late. I loved you too much to let you go! I could not bear the thought of you recoiling from me. Oh, I was mad—mad! I knew that I could not keep up the deception for ever, that you must find me out in time. But I had a wild hope that by then we should be so close to one another that you might find it in your heart to forgive. But I was wrong. I see it now. There are some things that no man can forgive. Some things,” she repeated, dully, “which no man can forgive.”

She turned away. Mortimer awoke from his trance.

“Stop!” he cried. “Don’t go!”

“I must go.”

“I want to talk this over.”

She shook her head sadly and started to walk slowly across the sunlit grass. Mortimer watched her, his brain in a whirl of chaotic thoughts. She disappeared through the trees.

Mortimer sat down on the tee-box, and buried his face in his hands. For a time he could think of nothing but the cruel blow he had received. This was the end of those rainbow visions of himself and her going through life side by side, she lovingly criticizing his stance and his back-swing, he learning wisdom from her. A croquet-player! He was married to a woman who hit coloured balls through hoops. Mortimer Sturgis writhed in torment. A strong man’s agony.

The mood passed. How long it had lasted, he did not know. But suddenly, as he sat there, he became once more aware of the glow of the sunshine and the singing of the birds. It was as if a shadow had lifted. Hope and optimism crept into his heart.

He loved her. He loved her still. She was part of him, and nothing that she could do had power to alter that. She had deceived him, yes. But why had she deceived him? Because she loved him so much that she could not bear to lose him. Dash it all, it was a bit of a compliment.

And, after all, poor girl, was it her fault? Was it not rather the fault of her upbringing? Probably she had been taught to play croquet when a mere child, hardly able to distinguish right from wrong. No steps had been taken to eradicate the virus from her system, and the thing had become chronic. Could she be blamed? Was she not more to be pitied than censured?

Mortimer rose to his feet, his heart swelling with generous forgiveness. The black horror had passed from him. The future seemed once more bright. It was not too late. She was still young, many years younger than he himself had been when he took up golf, and surely, if she put herself into the hands of a good specialist and practised every day, she might still hope to become a fair player. He reached the house and ran in, calling her name.

No answer came. He sped from room to room, but all were empty.

She had gone. The house was there. The furniture was there. The canary sang in its cage, the cook in the kitchen. The pictures still hung on the walls. But she had gone. Everything was at home except his wife.

Finally, propped up against the cup he had once won in a handicap competition, he saw a letter. With a sinking heart he tore open the envelope.

It was a pathetic, a tragic letter, the letter of a woman endeavouring to express all the anguish of a torn heart with one of those fountain-pens which suspend the flow of ink about twice in every three words. The gist of it was that she felt she had wronged him; that, though he might forgive, he could never forget; and that she was going away, away out into the world, alone.

Mortimer sank into a chair, and stared blankly before him. She had scratched the match.

I AM not a married man myself, so have had no experience of how it feels to have one’s wife whizz off silently into the unknown; but I should imagine that it must be something like taking a full swing with a brassey and missing the ball. Something, I take it, of the same sense of mingled shock, chagrin, and the feeling that nobody loves one, which attacks a man in such circumstances, must come to the bereaved husband. And one can readily understand how terribly the incident must have shaken Mortimer Sturgis. I was away at the time, but I am told by those who saw him that his game went all to pieces.

He had never shown much indication of becoming anything in the nature of a first-class golfer, but he had managed to acquire one or two decent shots. His work with the light iron was not at all bad, and he was a fairly steady putter. But now, under the shadow of this tragedy, he dropped right back to the form of his earliest period. It was a pitiful sight to see this gaunt, haggard man with the look of dumb anguish behind his spectacles taking as many as three shots sometimes to get past the ladies’ tee. His slice, of which he had almost cured himself, returned with such virulence that in the list of ordinary hazards he had now to include the tee-box. And, when he was not slicing, he was pulling. I have heard that he was known, when driving at the sixth, to get bunkered in his own caddie, who had taken up his position directly behind him. As for the deep sand-trap in front of the seventh green, he spent so much of his time in it that there was some informal talk among the members of the committee of charging him a small weekly rent.

A man of comfortable independent means, he lived during these days on next to nothing. Golf-balls cost him a certain amount, but the bulk of his income he spent in efforts to discover his wife’s whereabouts. He advertised in all the papers. He employed private detectives. He even, much as it revolted his finer instincts, took to travelling about the country, watching croquet matches. But she was never among the players. I am not sure that he did not find a melancholy comfort in this, for it seemed to show that, wherever his wife might be and whatever she might be doing, she had not gone right under.

Summer passed. Autumn came and went. Winter arrived. The days grew bleak and chill, and an early fall of snow, heavier than had been known at that time of the year for a long while, put an end to golf. Mortimer spent his days indoors, staring gloomily through the window at the white mantle that covered the earth.

It was Christmas Eve.

The young man shifted uneasily on his seat. His face was long and sombre.

“All this is very depressing,” he said.

“These soul tragedies,” agreed the Oldest Member, “are never very cheery.”

“Look here,” said the young man, firmly, “tell me one thing frankly, as man to man. Did Mortimer find her dead in the snow, covered except for her face, on which still lingered that faint, sweet smile which he remembered so well? Because, if he did, I’m going home.”

“No, no,” protested the Oldest Member. “Nothing of that kind.”

“You’re sure? You aren’t going to spring it on me suddenly?”

“No, no!”

The young man breathed a relieved sigh.

“It was your saying that about the white mantle covering the earth that made me suspicious.”

The Sage resumed.

IT was Christmas Eve. All day the snow had been falling, and now it lay thick and deep over the countryside. Mortimer Sturgis, his frugal dinner concluded—what with losing his wife and not being able to get any golf, he had little appetite these days—was sitting in his drawing-room, moodily polishing the blade of his jigger. Soon wearying of this once congenial task, he laid down the club and went to the front door, to see if there was any chance of a thaw. But no. It was freezing. The snow, as he tested it with his shoe, crackled crisply. The sky above was black and full of cold stars. It seemed to Mortimer that the sooner he packed up and went to the south of France, the better. He was just about to close the door, when suddenly he thought he heard his own name called.

“Mortimer!”

Had he been mistaken? The voice had sounded faint and far away.

“Mortimer!”

He thrilled from head to foot. This time there could be no mistake. It was the voice he knew so well, his wife’s voice, and it had come from somewhere down near the garden-gate. It is difficult to judge distance where sounds are concerned, but Mortimer estimated that the voice had spoken about a short mashie-niblick and an easy putt from where he stood.

The next moment he was racing down the snow-covered path. And then his heart stood still. What was that dark something on the ground just inside the gate? He leaped towards it. He passed his hands over it. It was a human body. Quivering, he struck a match. It went out. He struck another. That went out, too. He struck a third, and it burnt with a steady flame; and, stooping, he saw that it was his wife who lay there, cold and stiff. Her eyes were closed, and on her face still lingered that faint, sweet smile he remembered so well.

The young man rose with a set face. He reached for his golf-bag.

“I call that a dirty trick,” he said, “after you promised——”

The Sage waved him back to his seat.

“Have no fear! She had only fainted.”

“You said she was cold.”

“Wouldn’t you be cold if you were lying in the snow?”

“And stiff.”

“Mrs. Sturgis was stiff because the train-service was bad, it being the holiday-season, and she had had to walk all the way from the Junction, a distance of eight miles. Sit down and allow me to proceed.”

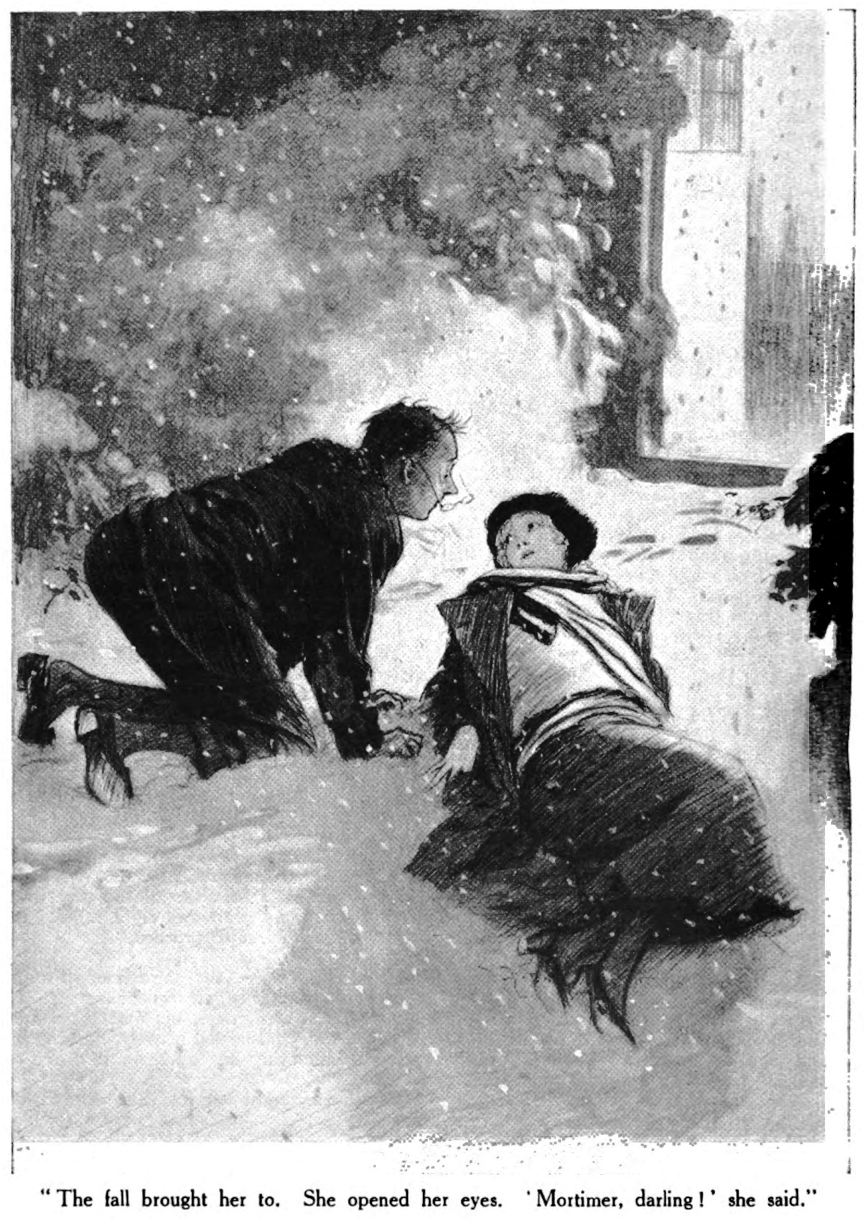

Tenderly, reverently Mortimer Sturgis picked her up and began to bear her into the house. Half-way there, his foot slipped on a piece of ice and he fell heavily, barking his shin and shooting his lovely burden out on to the snow.

The fall brought her to. She opened her eyes.

“Mortimer, darling!” she said.

Mortimer had just been going to say something else, but he checked himself.

“Are you alive?” he asked.

“Yes,” she replied.

“Thank God!” said Mortimer, scooping some of the snow out of the back of his collar.

Together they went into the house, and into the drawing-room. Wife gazed at husband, husband at wife. There was a silence.

“Rotten weather!” said Mortimer.

“Yes, isn’t it!”

The spell was broken. They fell into each other’s arms. And presently they were sitting side by side on the sofa, holding hands, just as if that awful parting had been but a dream.

It was Mortimer who made the first reference to it.

“I say, you know,” he said, “you oughtn’t to have nipped away like that!”

“I thought you hated me!”

“Hated you! I love you better than life itself! I would sooner have smashed my pet driver than have had you leave me!”

She thrilled at the words.

“Darling!”

Mortimer fondled her hand.

“I was just coming back to tell you that I loved you still. I was going to suggest that you took lessons from some good professional. And I found you gone!”

“I wasn’t worthy of you, Mortimer!”

“My angel!” He pressed his lips to her hair, and spoke solemnly. “All this has taught me a lesson, dearest. I knew all along, and I know it more than ever now, that it is you—you that I want. Just you! I don’t care if you don’t play golf. I don’t care——” He hesitated, then went on manfully. “I don’t care even if you play croquet, so long as you are with me!”

For a moment her face showed a rapture that made it almost angelic. She uttered a low moan of ecstasy. She kissed him. Then she rose.

“Mortimer, look!”

“What at?”

“Me. Just look!”

The jigger which he had been polishing lay on a chair close by. She took it up. From the bowl of golf-balls on the mantelpiece she selected a brand new one. She placed it on the carpet. She addressed it. Then, with a merry cry of ‘Fore!’ she drove it hard and straight through the glass of the china-cupboard.

“Good God!” cried Mortimer, astounded. It had been a bird of a shot.

She turned to him, her whole face alight with that beautiful smile.

“When I left you, Mortie,” she said, “I had but one aim in life, somehow to make myself worthy of you. I saw your advertisements in the papers, and I longed to answer them, but I was not ready. All this long, weary while I have been in the village of Auchtermuchtie, in Scotland, studying under Tammas McMickle.”

“Not the Tammas McMickle who finished fourth in the Open Championship of 1911, and had the best ball in the foursome in 1912 with Jock McHaggis, Andy McHeather, and Sandy McHoots!”

“Yes, Mortimer, the very same. Oh, it was difficult at first. I missed my mallet, and longed to steady the ball with my foot and use the toe of the club. Wherever there was a direction post I aimed at it automatically. But I conquered my weakness. I practised steadily. And now Mr. McMickle says my handicap would be a good twenty-four on any links.” She smiled apologetically. “Of course, that doesn’t sound much to you! You were a twelve when I left you, and now I suppose you are down to eight or something.”

Mortimer shook his head.

“Alas, no!” he replied, gravely. “My game went right off for some reason or other, and I’m twenty-four, too.”

“For some reason or other!” She uttered a cry. “Oh, I know what the reason was! How can I ever forgive myself! I have ruined your game!”

The brightness came back to Mortimer’s eyes. He embraced her fondly.

“Do not reproach yourself, dearest,” he murmured. “It is the best thing that could have happened. From now on, we start level, two hearts that beat as one, two drivers that drive as one. I could not wish it otherwise. By George! It’s just like that thing of Tennyson’s.”

He recited the lines softly:—

My bride,

My wife, my life. Oh, we will walk the links

Yoked in all exercise of noble end,

And so thro’ those dark bunkers off the course

That no man knows. Indeed, I love thee: come.

Yield thyself up: our handicaps are one:

Accomplish thou my manhood and thyself;

Lay thy sweet hands in mine and trust to me.

She laid her hands in his.

“And now, Mortie, darling,” she said, “I want to tell you all about how I did the long twelfth at Auchtermuchtie in one under bogey.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums