The American Legion Weekly, October 24, 1919

An English Master of Yankee Slang

A Writer Who Never Lets His Americans Say

“The Blighter Is Indeed a Rough Cookie”

P. G. Wodehouse has a jolly good time even when it is beastly hot and all that sort of thing, but he doesn’t let his American characters talk that way. He attributes his bi-slangual ability to deep study of such masters of English as Mutt and Jeff, Judge Rumhauser, Rube Goldberg’s Boobs, and the other children of the cartoonists.

TO the doughboy who shared trench and billet with the Tommy and to the gob who chased subs with the Limey, the idea of an Americanized Englishman is preposterous. Our men found the English good brothers-in-arms, but they found them exasperatingly lacking in the ability to absorb, assimilate or even understand American expressions and mannerisms.

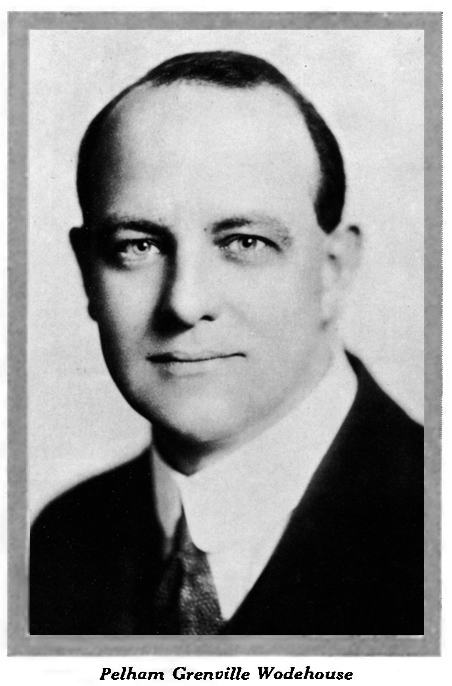

A magazine editor has called Pelham Grenville Wodehouse an Americanized Englishman. That this appellation is justified is shown by the fact that thousands who read the Wodehouse stories and see the Wodehouse plays do not suspect that he was—still is—a subject of George V, of the House of Guelph.

Few authors in America today are so prolific and entertaining as is Pelham Grenville Wodehouse. The short story, the novel, the musical comedy and the play, all are his fields.

He has sold more than 200 short stories and has published several novels. Last year twelve theatrical companies played theatrical offerings in the writing of which he took part. Most of these were musical comedies for which he wrote the lyrics.

Through some strange adaptability, Mr. Wodehouse has been able to write American, as distinguished from English. The language we speak in these United States is still referred to as English, but it is distinctively American and should be called so.

Usually, when an Englishman tries to write American, he produces results compatible with the artistic effects of a hod carrier attempting embroidery work. When he attempts slang he commits some such atrocities as, “Ah, yes,” said Mrs. Willoughby, “the dear blighter is indeed a rough cookie,” or “Tin the uncouth stuff, kid,” he said, angrily. “If you desire to shout, obtain a lease on an auditorium or some such sort of thing.”

Wodehouse writes for his American audience as though he has been one of us from birth. When he writes American slang he writes it as it is slung, with the ring of sincerity. The mystery of his adaptability grows with meeting him, for he is thoroughly English. He has a “jolly good time” even when it is “beastly hot” “and all that sort of thing.” But when he takes an American character into his fiction-framing mind, he makes it say just what an American would say under the circumstances. His speech is as subtly sprinkled with humor as his fiction.

THE source of Mr. Wodehouse’s slang vocabulary—he says he loves to use slang because it is a short cut to expression—is unusual. He is a student at those fonts of slang perpetrations, Mutt and Jeff, Judge Rumhauser, Happy Hooligan, Goldberg’s Boobs, and the other grotesque children of cartoonists’ pens.

Mr. Wodehouse is a keen student of human nature. One infers as much from his writings, but knows it better after meeting him and watching him watch others. People interest him, and it is because they do that he is able to interest them with his stories.

Mr. Wodehouse is 38 years old. He doesn’t look it. He’s a strapping fellow with the virility of youth in his eyes and his bearing. Not even a slight baldness indicates a birthdate of 1881. Writing is not drudgery for him. He has been doing it ever since he was a youth in school. Then he wrote boys’ stories that brought him only $10 and $15 each. Now the sums he receives for his stories are considerably in excess of those amounts. Before he left England he had received $70 for a story and his first effort in America brought what to him seemed an unheard-of price, $300. When he left school he started work in a bank. The employment wasn’t to his liking and it did not take him long to seek a new field. He chose newspaper work. He conducted a column for the London Daily Globe—one of those chatty English columns. He kept up his fiction writing and gradually branched away from his original line, boys’ stories, into the general field.

A five-week vacation while he was still in the newspaper field afforded Mr. Wodehouse an opportunity to visit America for the first time in 1904. It was just a short visit and he didn’t get out of New York, but America had won him when he sailed back, and five years later he returned to make this country his home.

He lives at Great Neck, Long Island, where, on a superannuated typewriter, to which is attached a tradition of superstition, he pounds out the Wodehouse stories. The typewriter was second-hand when he bought it and it shows still further signs of decrepitude now, but the first story that it turned out found a ready sale and it has been producing marketable goods ever since, so the author clings to it. He operates it with one finger of each hand, not the approved stenographic system, but quite fast enough for him, he says.

WRITING, itself, is the easiest part of his work, he says. When he sits down at his rustic typewriter there is little hesitancy about the flow. Before starting the actual writing, however, he outlines his plot and its development thoroughly.

The place isn’t important—last year he wrote a successful novel in hotel bedrooms as he toured the country with one of his plays. The time, however, enters into Mr. Wodehouse’s writing more or less. He does most of his work in the morning, not because he writes any better at that time, but because he is lured to a golf course if he delays work, and once at golf he forgets fiction.

Mr. Wodehouse has been a reigning magazine favorite for several years. His days are full—work in the morning, golf in the afternoon, and in the evening study, that is, study of the day’s cartoon slang.

This article gives evidence of Wodehouse’s study of American comic strips, which accords well with speculations about his presumably unconscious borrowing of a character name, J. Filliken Wilburfloss, from a 1909 New York newspaper cartoon. See the note at the end of Psmith, Journalist, episode 4.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums