The Captain, April 1905

I.

HERE

was not a great deal of Master Reginald Rankin, of Seymour’s—he weighed seven

stone three—but his acquaintances objected very strongly to all that there

was. Reginald, indeed, did not court popularity. He had not that winsome,

debonnair manner which characterises the Social Pet. He was small and ugly. His

eyes, which were green, wore a chronic look of suspicion and secretiveness. In

fact, the superficial observer, who judged only by appearances, would have

summed him up without further trouble as a little brute.

HERE

was not a great deal of Master Reginald Rankin, of Seymour’s—he weighed seven

stone three—but his acquaintances objected very strongly to all that there

was. Reginald, indeed, did not court popularity. He had not that winsome,

debonnair manner which characterises the Social Pet. He was small and ugly. His

eyes, which were green, wore a chronic look of suspicion and secretiveness. In

fact, the superficial observer, who judged only by appearances, would have

summed him up without further trouble as a little brute.

The superficial observer would have been quite right. He was.

Reginald’s hobby was Revenge. I hope the printer will not fail to use a capital R for that word. A small letter might send the reader away with the impression that the Revenges of Reginald were of the same hasty, unscientific kind as those affected by the average boy. If the average boy is kicked on the shin by an enemy, he kicks back, and goes on his way rejoicing, and the episode is closed. Not so Reginald. One of his most treasured possessions was a small leather-covered diary of the sort one’s aunt gives one at Christmas. In this he entered the important events of each day, and, unlike most people, he did not grow tired of it on January the third, and leave the rest of the year blank. He went conscientiously through the whole three hundred and sixty-five days; and, read as a consecutive story, it was not uninteresting. Thus, if one had been privileged to probe its mysteries, one would have found on March the sixth the following entry:—

“Got up. Washed. Said my prayers.

(The last two statements rest on the unsupported word of the author. Neither feat produced any noticeable result.)

Continuing:—

“After breakfast Smith said I was a little beast, and smacked my head. Got turned in Livy. Templar gave me the lesson to write out.”

The next entry of interest is March the eighth, where we see Mr. Templar rewarded for his trouble: “Ragged a lot in form.”

All this while Nemesis has been hovering over the too truthful Smith. The incident of Mr. Templar has been a parenthesis. Honour, as far as Smith is concerned, remains unsatisfied. A whole week elapses before our hero gets his own back. All that while one imagines him dogging his victim’s footsteps remorselessly. At last, on March the thirteenth, this item leaps to the eye:

“Got up. Washed. Said my prayers. Hid Smith’s boots, and he was late for school and got two hundred lines. Beef for dinner, and some muck that looked like plum pudding. Wrote home for money. Said my prayers. Went to bed.”

Exit Smith, properly punished.

With which excursus on the manners and customs of the ruthless one, we can begin our story.

Rankin fagged for Rigby, of the Sixth. In this he was fortunate; for Rigby, as a rule, when he was not wrestling with some obstinate set of Iambics or Elegiacs, was of a placid nature, and rarely fell foul of those who fagged for him. And when he did, he merely relieved his feelings with sarcasm, the same passing over Rankin’s head so completely that he generally imagined that he was being complimented. Yet even Rigby got into Rankin’s black book.

It happened in this way.

The architect who had built Mr. Seymour’s house was a man with a quiet, but strongly marked, sense of humour. The place was full of quaint surprises. One of his original effects was to cause the partition wall between Rigby’s study and the one adjoining it to stop short of the ceiling by a couple of feet. How he hoped to benefit his fellow-man by this is not known. Probably, he reflected that the used-up air of one study would be enabled to escape into the other, and vice versâ, a healthy and incessant ventilation being thus secured. At any rate, there the opening was, and it had never been filled up.

When Rigby got his study he lodged a complaint. Two chatty persons, named Dent and Hammond, dwelt next door, and when three consecutive nights’ work had been spoiled by the conversation which flowed over the wall in an unceasing stream, he flung down his Liddell and Scott and bounded off to the house-master. Since when the next-door study had been empty.

But even then his troubles had not ceased altogether. Time sometimes hung heavy on the hands of the Senior Day-room, and when this happened it was the custom with the gay sparks who led the revels in that den of disorder to adjourn to the vacant study (having first ascertained that Rigby was at home and hard at work) and make weird noises there. When the goaded worker finally plunged in to investigate with a stick, he found the room bare and empty, while the sound of receding footsteps in the distance told him that the revellers, much refreshed, were returning to their own quarters. These little things irritated Rigby.

Now it chanced one evening that Linton and Menzies, of the Senior Day-room, prowling the passages in search of adventure, came upon Rankin near Rigby’s door.

“Hullo,’’ said Linton, “lost anything?”

“No,” replied Rankin, edging away suspiciously.

“You look as if you were looking for something. Do you want to find Rigby?”

“No,” said Rankin, essaying a flanking movement.

“Don’t you be an ass,” said Menzies kindly. “You must want to see Rigby. You’re fagging for him, and if you don’t go to him you’ll get into trouble. I’m sure he wants you now. Come on.”

The procession passed into the empty study. From the other side of the wall heavy breathing could be heard. The sound of a great soul struggling with a line that would not “come out.”

“Let go, you cads!” shrilled Reginald.

“Stop that beastly row there!” shouted Rigby from the other study. “Is that you, Rankin? Come here. I want you.”

“I told you so,” whispered Menzies. “Come along. Better go by the short cut.”

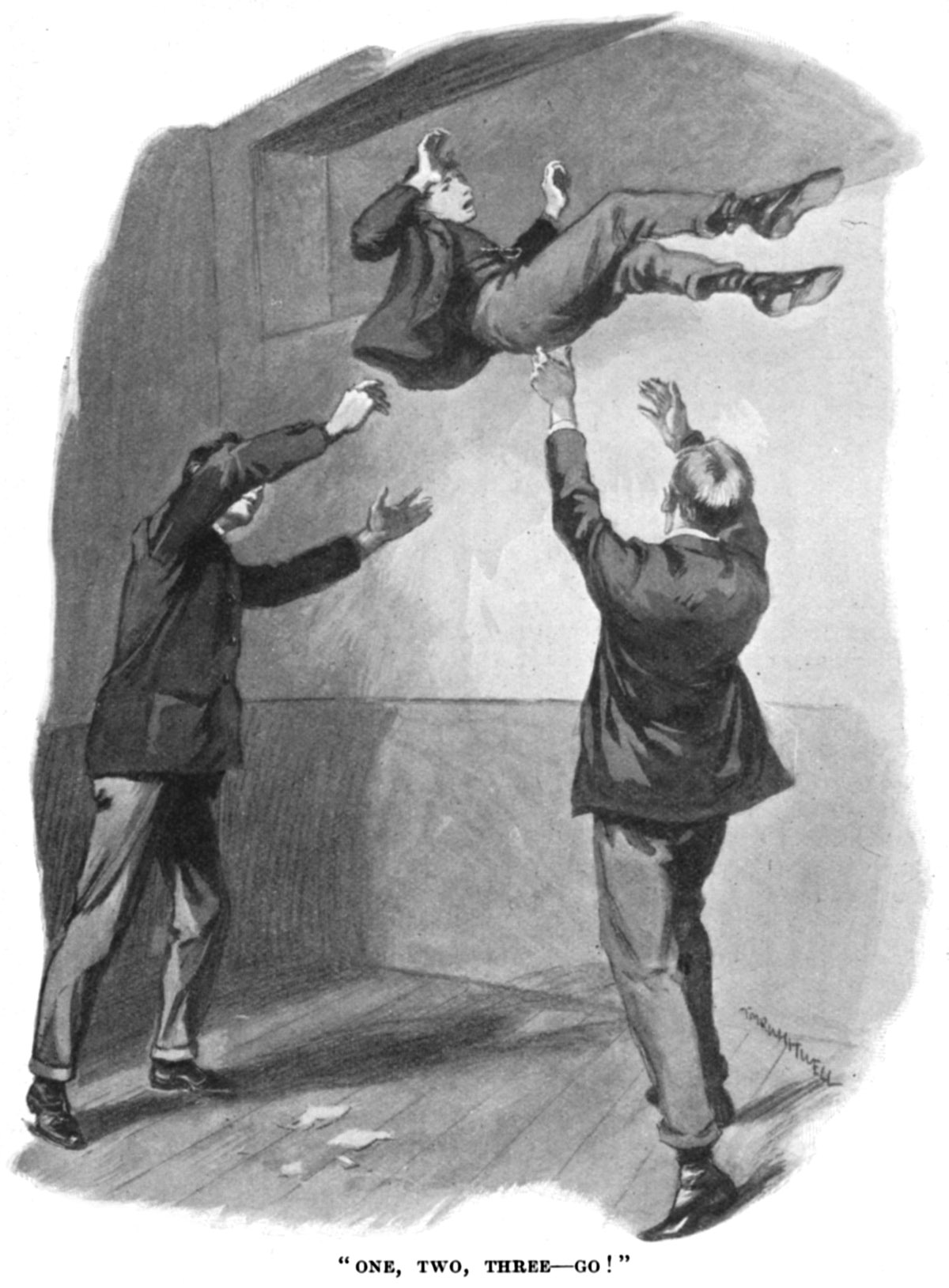

He grabbed Rankin by the knees.

“Saves time,” agreed Linton, attaching himself to Rankin’s shoulders. “One, two, three—go!”

“Do you hear, Rankin?” said Rigby.

“Come here.”

And Reginald came.

What followed was distinctly a miscarriage of justice. When Rigby had picked up—in the following order—himself, his table, his chair, his books, his pen, and his ink-pot, and mopped up the last drop of ink on his waistcoat with his last sheet of blotting-paper, he proceeded to fall upon the much-enduring Reginald with the stick which he took with him to church on Sundays. Long before the interview concluded, Reginald had reason to regret that it had not been left behind in the pew on the previous Sabbath.

In the case of another hero in similar circumstances we read that “Corporal punishment produced the worst effect upon Eric. He burned, not with grief and remorse, but with rage and passion.” Or words to that effect. Just so with our Reginald. His symptoms were identical. In his diary for that day the following entry appears:—

“Got up. Washed. Said my prayers. After school two cads, Linton and Menzies, heaved me over the partition wall bang on to Rigby’s table, and Rigby licked me when it wasn’t my fault at all. He is a beast. Said my prayers. Went to bed.”

After preparation that night Linton and Menzies, talking it over, came to the conclusion that the sequel to the affair must be a confession. They had little sympathy with Rankin, but the code of etiquette at Wrykyn demanded that he who got another into trouble should own up, and take all that was going in the matter of consequences. So Linton and Menzies went to Rigby’s study. Rigby was immersed in some work which was apparently disturbing him a little. His hair was rumpled, and he was turning over the pages of his lexicon with feverish rapidity.

“Get out,” he said, when the pair made their appearance. “What do you want?”

“It’s only about this afternoon,” said Linton.

“What about this afternoon?” said Rigby, putting in a spell of rapid finger-work with the pages of the lexicon. “What does—oh, it’s all right, I’ve got it. Well, go on. Don’t be all night.”

“About Rankin,” said Menzies, gently, as one explaining to a lunatic.

“Pushing him over, you know,” said Linton.

“We did it,” said Menzies.

“Did what?” said Rigby, from the depths of the lexicon.

“Shoved him over the wall,” said Menzies patiently.

“Yes?” said Rigby, in an absent tone of voice. “I wonder what—oh, here it is. Now, what do you chaps want? If you can’t come to the point and talk sense, get out. Can’t you see I’m busy?”

“We thought you ought to know that it was us who shoved Rankin over the wall on to your——” He stopped. Rigby’s head was bent over the lexicon.

“Good-night, Rigby,” said Menzies.

“Good-night,” said Rigby.

And the pair departed. They had done their best. It was not their fault if the man refused to listen to their chivalrous explanations.

Rigby worked on till the gas went out suddenly, as was its habit. Then he went to bed, and in the small hours the purport of Menzies’ visit dawned upon him, and he realised that for all practical purposes he had been the Beetle-Browed Bully that afternoon, ill-treating the innocent small boy without cause or excuse. His was a genial nature, when not roused, and he resolved to make it all right with Rankin on the following morning.

After breakfast, accordingly, he summoned him to his study, made what was, in the circumstances—from prefect to fag—a handsome apology, and then dismissed the matter from his mind in favour of the second book of Thucydides, satisfied that the Entente Cordiale was sealed.

II.

But in the black depths of Reginald’s soul the desire for Vengeance still remained. Apologies are good enough in their way, but there are some things which cannot be wiped out by apologies. Reginald was not yet able to sit down with any comfort.

A lesser injury might have been repaid by the burning of toast or the over-boiling of an egg, but for a special case such as this Reginald scorned these obvious modes of retaliation as inadequate. This was an occasion for really drastic measures. Rigby thus escaped punishment for a season. And then, while the avenger was halting irresolutely between the various modes of retribution open to him, Fate, by the medium of a mild illness, removed his intended victim to the secure retreat of the Infirmary. Reginald felt as those Homeric warriors must have felt who, when they had, after great trouble, succeeded in rattling an opponent, had the mortification of seeing him rescued by some local god of unsportsmanlike nature, and conveyed to a place of safety in a special cloud.

One afternoon, however, he received a message from the invalid. Rigby wanted to see him at the Infirmary. It was important, said the message.

Reginald went to the Infirmary, where he found his foe lying on a sofa, reading an old volume of Punch. There was a pleasant fire blazing in the grate, and the whole aspect of the room, with its air of snugness and luxury, deepened his sense of injury. Not only had Rigby been permitted to evade his rightful punishment, but he was, in addition, being Pampered.

“Come in, Rankin,” said the sufferer. “Look here, I’ve got something for you to do. My uncle and aunt are coming down to-morrow, and they’ll want to see my study after they’ve looked me up here. So you might do the honours. And there’s another thing. On the second shelf of my book-case you’ll find a crib to the ‘Agamemnon.’ You’d better cart that away and hide it till they’ve gone. My uncle’s a bishop, and he has views of his own on cribs. Thinks they’re deceitful. See? You’ll know the book. It’s blue, and it’s one of Bohn’s series. Don’t forget. And mind the study’s tidy. Thanks. Shut the door.”

Reginald shut the door gently. A sudden thought had come,

“like a full-blown rose,

Flushing his brow.”

He meant to make that study very tidy. If ever there was a tidy study on the face of the earth, this tidy study was going to be that tidy study. But with respect to details he intended to exercise a certain license.

There lived in the town of Wrykyn one J. Mereweather Cooke, a day-boy. Having been associated with him in dark deeds, Reginald had formed an alliance with him. Cooke’s father was a sporting doctor. To the maison Cooke Reginald therefore made his way after leaving the Infirmary.

“I want to borrow some books,” he said. “Can you bag any of your pater’s?”

“What sort of books?”

“Oh, anything. Let’s have a look, and I’ll choose.”

He chose.

III.

This was the letter.

The Station Hotel, Wrykyn.

My Dear George (Rigby’s name was George),—I am both grieved and disappointed. I have no wish to be unduly harsh with you at a time when you are laid up, but my duty compels me to speak out.

It seems incredible, I know, but I regret to say that my dear George’s impression after reading so far was that his uncle had been lunching.

He read on.

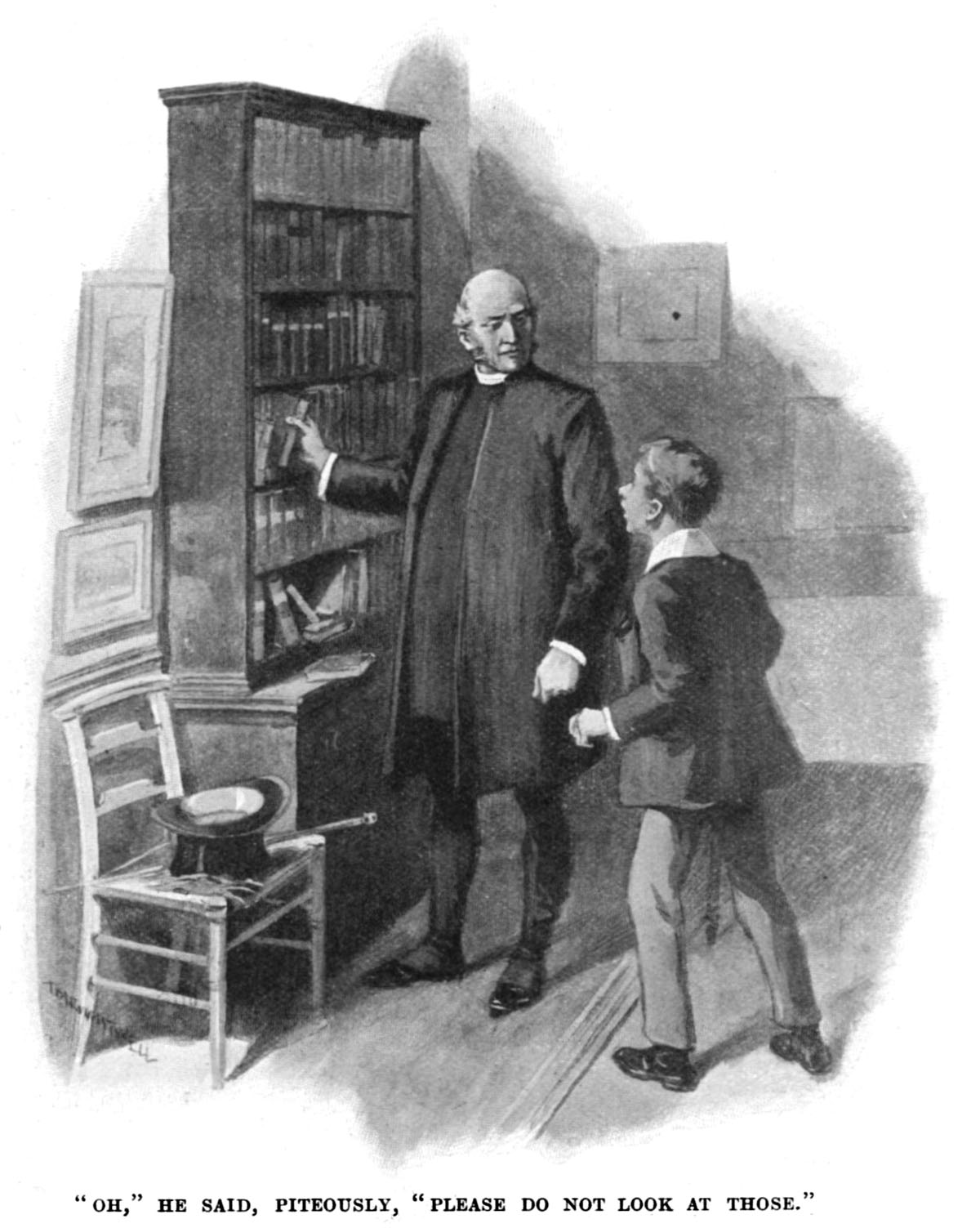

That you were not wholly free from the failings of boyhood I was aware. I knew you to be in a measure deficient in reverence for your elders, and thoughtless. But I did not dream that you were also deceitful. My visit to your study to-day convinces me that I was wrong. Escorted to the room by a small lad, who was throughout most polite, I found on your shelves such an array of Dr. Bohn’s English Translations of the Classics as I could not have believed (but for ocular evidence) to have existed at one of our public schools. Nor is that all. Seeing me glancing at these volumes, the small boy to whom I have alluded uttered an irrepressible cry of mental distress. “Oh,” he said, piteously, “please do not look at those. He told me to hide them, and said he would beat me if I did not.” I have underlined those words, George. That you should so corrupt the mind of one of your juniors (to whom you ought to set a good example) is bad; but that you should force him with blows to carry out an act offensive to his conscience is worse, far worse. This petty tyranny did not, however, avail you, for I observed the books. In addition to these deceitful aids to study, I regret to say that I noticed other evidences of a perverted taste not often to be found in one so young. Of a dozen or more yellow-covered novels (so-called) I can recall the titles of but two, Jenny, the Girl Jockey, by Hawley Gould, and A Tale of the Stableyard, by Nat Smart. That you might have no more money to waste on such trash, I decided to give the sovereign with which I had intended to present you, to the small lad of whom I have made mention. I shall hope to see you when you return home for your holidays. Meanwhile,

I am, your uncle,

Peter Peckham.

Ten minutes later Rigby, having pondered deeply over the matter, and traced his misfortunes to the right source, asked the Infirmary matron if she would be good enough to send for Rankin, as he had something very particular and important that he wished to say to him.

The reply came back, per messenger.

Master Reginald Rankin presented his compliments to Mr. Rigby, and very much regretted that one of those unfortunate previous engagements rendered it impossible for him to accept his kind invitation to come and listen to something very particular and important.

Two days after breaking-up day Rigby came out of hospital.

When the school re-assembled on the last night of the holidays, Rigby smiled a glad smile, and sought out the Seymour’s matron.

“Oh, has Rankin come back yet?” he asked winningly. “I’ve got something rather particular and important to say to him.”

“Rankin?” said the matron. “Oh, Rankin. No, he’s left the house. His parents have come to live in the town, and he is a day-boy now.”

“Oh,” said Rigby.

And he moved away disappointedly, feeling that some considerable time would probably have to elapse before he got square with Master Reginald Rankin.

(Next Month: “The Politeness of Princes.” )

Notes:

seven stone three: 101 pounds.

got turned in Livy: got chastised for failing to translate this Roman historian (Titius Livius, 59 bc–17 ad). At Marlborough School at this time, “turn” meant to chastise with a cane or stick.

Liddell and Scott: a standard Greek-English lexicon; revised editions are still in use today, available online.

another hero . . . Eric: Eric, or Little by Little (1858), by Frederic W. Farrar, a novel of school life.

crib: a printed translation, especially one used as a shortcut by students. See Wodehouse’s essay “Treating of Cribs” from the Public School Magazine.

lunching: here, a euphemism for having drinks with lunch.

Dr. Bohn: Henry George Bohn (1796–1884), a British publisher of popularly-priced uniform editions of standard works and translations of classics.

Hawley Gould and Nat Smart: These authors, and the titles named, are fictional, but the names are derived from real-life authors. Captain Hawley Smart (1833–1893) wrote 38 entertaining novels of society, military life, racing, and hunting, appealing to popular tastes rather than to literary critics. Nat Gould (1857–1919) worked as a journalist in Australia, where he began writing novels serialized in sporting newspapers, mainly about horse racing; one, Harry Dale’s Jockey “Wild Rose” (1894), featured a young woman jockey. Upon his return to England he continued writing fiction, and completed about 130 books, selling many millions of copies in all. [Thanks to Karen Shotting for identifying these originals.]

—Notes by Neil Midkiff

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums