The Captain, August 1905

NCE,

on an average, in every four years, there comes to most public schools such a

season of athletic prosperity that many who would, in ordinary years, have been

certain of places in the first eleven or fifteen have to be content with second

caps. This happened at Wrykyn in the year when Trevor was captain of football

and Henfrey captain of cricket. The fifteen won all their school matches and

most of the club games, and, which only happened at very rare intervals, beat

Ripton twice. The cricket team did, if anything, better. All the four schools

they played went down before them. The M.C.C., who brought a poor team, were

positively massacred; and the O.W.’s were beaten, though including in their

ranks three county men, one of whom had been in the last English eleven to

Australia.

NCE,

on an average, in every four years, there comes to most public schools such a

season of athletic prosperity that many who would, in ordinary years, have been

certain of places in the first eleven or fifteen have to be content with second

caps. This happened at Wrykyn in the year when Trevor was captain of football

and Henfrey captain of cricket. The fifteen won all their school matches and

most of the club games, and, which only happened at very rare intervals, beat

Ripton twice. The cricket team did, if anything, better. All the four schools

they played went down before them. The M.C.C., who brought a poor team, were

positively massacred; and the O.W.’s were beaten, though including in their

ranks three county men, one of whom had been in the last English eleven to

Australia.

It may be imagined, therefore, that there was some competition for places in the team. There were eight old colours, which left only three caps for the twenty odd second- and third-eleven men who wanted them.

At the beginning of the summer term it was found that Strachan had not returned, and news came that he was ill at home with scarlet fever. Strachan, who played back for the school fifteen, was a reckless, hard-hitting bat and a useful field. He had got one of the last places in the team of the previous year, and was the eighth of the eight old colours mentioned above. Henfrey bore his loss philosophically enough, having such magnificent material to his hand with which to fill the vacant place, wrote him a letter of sympathy, telling him to come back as soon as he could, and in the list for the first school match, against the Emeriti, included Ellison and Selwicke, both of Donaldson’s.

In an ordinary season both of them would have been high up in the team on their form of that year. Three years later they were playing for Oxford together. They were good, stylish bats, curiously alike in method, and they fielded beautifully, Ellison at third man, Selwicke at cover. Out of the cricket-field they were inseparable. Wrykinians as a class were rather inclined to hunt in couples, but Selwicke and Ellison lowered all records. For years, since the days when they had been fags, they had walked to school together, sat next to one another in form, gone for afternoon strolls together on Sundays, boated together, and prepared their work together. They were now in the Sixth together, and house prefects. They did not share one study, but they were so constantly in each other’s dens that it amounted to that. In the holidays, it was believed, they visited each other’s homes. The school knew curiously little of them except the fact that they were good at games. It was said that they were good sorts, but the firm was so self-sufficient that it did not recognise the necessity of knowing anybody outside it. They were very quiet, and not even Trevor or Clowes, who had gone up the school with them and been in the same house for five years, could remember an occasion on which they had let themselves go, and plunged into any public escapade. There were single hermits at Wrykyn, though not many, fellows who seemed to know nobody and to want to know nobody, but the Ellison-Selwicke combination was the only case of a firm of hermits.

The match against the Emeriti resulted in a fairly easy win for the school. Ellison and Selwicke were at the wickets together towards the middle of the innings, and scored respectively twenty-nine and thirty-one. Ellison caught a couple of catches at third man, Selwicke held a nice one at cover. Each came out of the ordeal, therefore, with credit, and, as might have been expected, with equal credit. One could not imagine either of the two making a century to the other’s duck. One expected a neat twenty or thirty from both. Clowes and Trevor talked the match over that night after tea. Both were certain to be in the eleven at the end of the season. Trevor was an old colour, and, after Jackson and Henfrey, perhaps the best bat on the side. Clowes, though not a great bat, was sure of his place as wicket-keeper.

“What did you think of Ellison’s innings?” asked Clowes.

“Good,” said Trevor.

“And what did you think of Selwicke’s?”

“Good,” said Trevor again.

“Not much to choose between them, was there? And there never will be, either. You see. As long as Henfrey goes on playing them they’ll each make exactly the same number of runs in exactly the same sort of way, and they’ll each field exactly as well as the other. I tell you what, Trevor, and that is that there’s brain-fag waiting for our popular and energetic skipper. He can put it off, but he’s got to have it. What would you do in his place? I should cry, I think.”

“But there are three places,” said Trevor.

“Nothing escapes you,” said Clowes admiringly. “On the other hand, in my modest way I had already bagged one of the said three for myself. At any rate, if they don’t have me—and I shall bring an action if they try to turn me out—that won’t affect Ellison and pard. Because they’ve got to have a wicket-keeper, and, if it’s not me, it’ll be Dunstable or some one in the third.”

“Yes, you’re right there.”

“I’m always right,” said Clowes. “They call me Archibald the All Right, for I am infallible. Then there’s Milton. He must get one of the vacant places for his bowling. You must have a fast bowler in the team. And if Milton didn’t get in, which he will, that, again, wouldn’t let in Ellison or Selwicke. They’d give the place to some other bowler. Clephane, perhaps; only he’s too erratic. So, however you look at it, there’s only one place for the two of them. And, I tell you what, if this doesn’t smash up the firm, I shall be surprised. I could imagine David quarrelling with Jonathan if they both wanted the same place in a cricket team.”

“I hope it won’t,” said Trevor. “I rather like seeing two chaps pals like that. They don’t interfere with anybody, and they give the house a leg-up whenever they can.”

The house was Trevor’s hobby.

“So do I hope it won’t,” said Clowes. “Who said they hoped it would? I used to be sick with them at one time, but it amuses me now. Still, it’ll be interesting watching the effect of this on them. If anybody came between me and that cap for which I hope shortly to write to Devereux, I should feel it my painful duty to blot him off the face of the globe. I should feel that he wasn’t wanted, that he didn’t fit into the general scheme of utility. And I bet that’s what Ellison and Selwicke ’ll be feeling before long. You watch ’em. And, in the meanwhile, lest we become rusty in the noble language of old Greece, make a long arm and hoik down yon ‘Prometheus Vinctus,’ and let’s do a little work for a change. For slackness,” said Clowes, opening his Bohn’s English translation, “I can’t abear.”

Clowes was right. Slowly but surely the rivalry began to have its effect on Selwicke and Ellison. There was something almost ludicrous in the way they kept together in their cricket performances. Against the Gentlemen of the County Ellison made twenty-five. Selwicke replied with twenty-four. In the first of the school matches Selwicke had made nine and Ellison ten, when Henfrey declared the innings closed. Without inflicting upon the reader their full scores in every match, it may be said that three-quarters of the way through the term there were not a dozen runs between them. They had played in every match, and neither had failed nor yet achieved a big success. Useful twenties and thirties stood to their names in the score sheets of every match.

Henfrey was not disturbed. As far as he was concerned, all was well. He had not to decide on the final composition of his team till after the return match against Ripton, three weeks away. And, meanwhile, he had two absolutely reliable men to go in sixth or seventh and knock up a nice little score as a background to the scintillations of Jackson, Trevor, O’Hara, or himself earlier in the innings. He was not going to worry himself yet about which of the two must have his cap. “Sufficient unto the day”—he felt. He gave Milton his colours after the M.C.C. match, and Clowes his after the game against the old Wrykinians. But the last place remained open; and Selwicke and Ellison grew more silent than ever. They avoided one another now. It had started in a small way, by Ellison omitting to come to his friend’s study to work, but it grew till sometimes they barely spoke half a dozen times to one another in the day. Like the heroes of Mr. Gilbert’s “Etiquette,”

“At first they didn’t quarrel very

openly, I’ve heard.

They nodded when they met, and now

and then exchanged a word.

The word grew rare, and rarer still

the nodding of the head,

And when they meet each other now,

they cut each other dead.”

It was a pity. But when two dogs want the same bone, there is always unpleasantness.

“What did I tell you?” said Clowes to Trevor.

“Fools—they are,” growled Trevor. “What’s it matter, when you come to think of it! In another five years nobody’ll remember they were at the school.”

“It’s all very well to say that,” said Clowes, “and thank you very much for the moral reflection, but I should like to see you if somebody tried to bag your place in the first.”

A fortnight before the Ripton match the situation was further complicated by the reappearance of Strachan, who turned up at the school thin but cheerful. There was one match before the game which would settle the team for good and all, for, as in the case of the fifteen, it was a school tradition that the eleven which played against Ripton in the return match should be the official Wrykyn eleven. This last remaining fixture before Ripton was against the Incogniti, and took place a week after Strachan’s return. All through that week the ex-invalid had been practising hard at the nets, and it was certain that he would play against the Incogs. The excitement in the school was great now that it seemed that Henfrey must make his choice between the two rivals. Selwicke and Ellison went about looking gaunt and anxious.

And after all the choice was not made. When the list went up on the Friday morning the school, crowding round the notice-board, saw that the two names still figured on the list. Strachan’s was there also. Examination revealed that O’Hara was not playing. And presently authoritative information came (through the fags of the house) that O’Hara had bruised his right hand, and that, in order to ensure its being serviceable against Ripton, he intended to rest it for a few days.

There must have been a bigger gathering at that Incogs. match than at any other match on the school grounds for years. Not even the Ripton matches had aroused such interest. There was a sporting flavour about this long-drawn-out duel between the Damon and Pythias of Donaldson’s which appealed to the school.

By five o’clock the match was in a most exciting state. The Incogs. had batted first. They had brought down a sound side, with a Middlesex man who had scored a double century against Essex during the previous week, in command, and quite a number of well-known players in the ranks. The Incogniti did not intend to make the mistake the M.C.C. had made. They recognised that the Wrykyn team this year was an uncommonly good one. Starting on a good wicket, the earlier batsmen had helped themselves freely off the school bowling. At lunch time a hundred and forty was on the board, and only three wickets were down. But lunch had had its effect on the eye of the visiting team. Milton, in the course of a couple of very destructive overs immediately after the start, had disposed of three men, including a dangerously adhesive gentleman who had made seventy before the interval. After this the game settled down. The tail wagged comfortably, and the total score when Clowes whipped the last man’s bails off at a moment when that impulsive player had gone out of his ground to the extent of a couple of yards in order to hit one of Allardyce’s slows into the pavilion, was two hundred and eighty-one.

The Wrykyn ground was made for fast scoring. The turf was hard and dry, and the ball travelled beautifully, like a red streak along the green. The school went in at three o’clock confidently. Eighty an hour is quick work, but on just such a day as this, in the Masters’ Match, runs had come at the rate of ninety an hour and more. Wrykyn never played for a draw, and to-day they meant to win, even if it entailed the taking of risks.

And so at five o’clock it came about that, with four wickets down, the school had one hundred and sixty-three runs to its name. So far the rate of scoring had been exactly right. Some good men had gone in the amassing of those hundred and sixty-three runs. Henfrey was out: l.b.w. 31. Worse still, Jackson was out: clean bowled 54. Trevor had knocked up a beautiful seventy before being caught in the slips; but Strachan, after scratching about miserably for a few minutes, had been yorked for six. Allardyce was in at one end. At the other was Clowes. Neither had scored.

For some overs the scoring was slow. Then Clowes got the fast bowler away for a couple of fours. Off the next ball he was caught at third man.

Ellison came in. He played the last ball of the over, but half-way through the next Allardyce’s leg stump was knocked askew by a lovely length-ball from the slow bowler. The score was now one hundred and seventy-nine, and six wickets were down.

Selwicke was the next man. There was a stir of excitement round the ropes as he walked down the pavilion steps. The school clapped encouragingly. The interest was twofold. Would Wrykyn save the match? And would Selwicke do better than Ellison, or vice versâ?

Selwicke took guard amidst a profound silence, and played the remaining balls of the over carefully. Both he and Ellison were always slow starters.

Soon it began to be apparent that they had played themselves in. The rot was stopped. Selwicke hit the fast bowler twice past cover, scoring seven by the strokes. Ellison took eight off the slow bowler. Two hundred went up on the board. Ellison had made eleven, Selwicke ten.

Selwicke glanced the fast bowler to the boundary. It looked as if the two were going to knock off the runs. The opinion of the school was that each would make forty not out and that Henfrey would get brain fever.

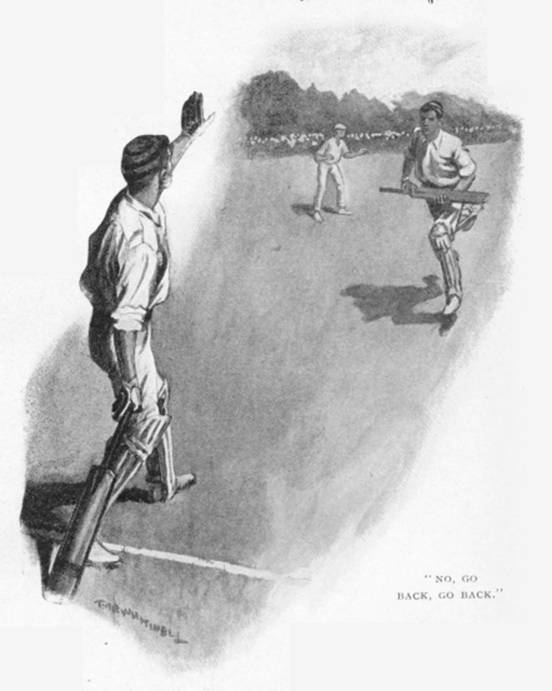

But the very next ball the gruesome thing happened. It was a short, fast ball. Selwicke got well over it and cut it crisply to third man. Third man just reached it. For a moment Ellison thought he had let it pass him.

“Come on,” he shouted. Then in the same breath, in an agonised yell, “No, go back, go back.”

But Selwicke was already half-way up the pitch. Back came the ball, and off went the bails. The wicket-keeper looked a query at the umpire. The umpire’s hand went up, and Selwicke, white as a sheet, turned sharply off to the pavilion. There was a dead silence all round the ground.

“Hard lines, sir,” said the wicket-keeper consolingly. Selwicke made no reply.

Ellison stood where he was, as if he had been frozen. There seemed to be lead in his chest. The sun seemed to have gone in, and a chill wind to have begun to blow. He walked down the pitch, and tapped a worn spot mechanically with his bat. He felt as if he were in a dream. He could feel vaguely that somebody had just committed the most stupendous act of folly on record, and he seemed to know the fellow, and be sorry for him. The suddenness of the thing had stunned him.

“Man in!” said somebody.

He looked up, and saw Milton walking to the crease. His first impulse was to get himself out, to knock his wicket down, as a sort of atonement. But he realised in time that he must do his best to win the match for the school. But he longed to hear the rattle of the stumps behind him. If only they would get him out before he could make any more!

But somehow no bowling he had ever played had seemed so absurdly easy. How could a fellow be expected to get out against such stuff! Soon he began to feel a sort of dull fury at the feebleness of it. He hit out viciously. There were roars from the school on the ropes. The incident of the run-out was forgotten in this brilliant display of hitting. Every over the ball skimmed along the turf and flew under the ropes. It’s your fault, Ellison kept saying to himself; you shouldn’t bowl such muck. And yet the bowling was fully as good as it had been during the earlier part of the innings, and Milton, at the other end, was in considerable trouble whenever he had to face it.

Two hundred and fifty went up. Another over from the slow man, and two hundred and sixty succeeded it. There was a brief consultation among the authorities. Then the field spread out like a fan. Ellison laughed savagely to himself. What was the good of lobs?

The lob-bowler’s name was Saintsbury. If you look at the analysis of that match in the Wrykinian you will find:

Overs. Maidens. Runs. Wickets.

Saintsbury, E. J. . 1 0 24 0

Ellison hit every single ball full-pitch over the boundary, and the Incogniti helped to chair him into the pavilion.

“The man’s a lunatic!” said Henfrey, some hours later that evening, as he read the letter Ellison’s fag had brought him.

“Dear Henfrey [it ran],—It is very good of you to offer me my colours for the first, but I’m afraid I cannot accept them. I would much rather you played Selwicke against Ripton. He was quite set when I ran him out, and but for my folly would have made a century.

“Yours faithfully,

“G. B. Ellison.”

“He’s off his dot,” said Henfrey. “Of course, he feels raw about that run out; but Selwicke couldn’t play an innings like that if he tried all the summer. And yet Selwicke’s a jolly good bat. I wish—but it can’t be helped.”

It was to be proved, however, that it could. As Henfrey was going to his dormitory that night, he was stopped by Strachan. Strachan was very calm and business-like.

“Made out the list for Ripton yet, Henfrey?”

“Not written it yet. But of course Ellison gets the place. Chap who can make an eighty-three like that——!”

“Half a second,” said Strachan. “I just wanted to speak to you about that. Put in Ellison, of course. And put in Selwicke, too. I’m not going to play.”

“Not going to play!”

In spite of himself Henfrey could not help feeling pleased. He had not even thought of such a solution of his difficulty, but it was the very best possible. Poor old Strachan was dead out of form. Selwicke was worth two of him at present.

“No,” said Strachan, “I thought I’d make this afternoon’s game a test, and I found I’d lost all my hitting powers. No nerve either. So I’m no good. Be all right next year, I suppose. So count me out. See?”

“Well, if you really——” said Henfrey.

“That’s all right,” said Strachan. “Good night.”

“One minute. I see how we’ll manage it. You’ll keep your cap, of course. It’ll be quite in order, you know, as you’ve been ill. ‘Not placed.’ There’ll be twelve caps instead of eleven this year.”

“All right. So long as you get Ellison and Selwicke in, I don’t care what you do. Good-night.”

“Good-night. I say, Strachan.”

“Hullo ?”

“Er—you’re a good chap,” said Henfrey gratefully.

. . . .

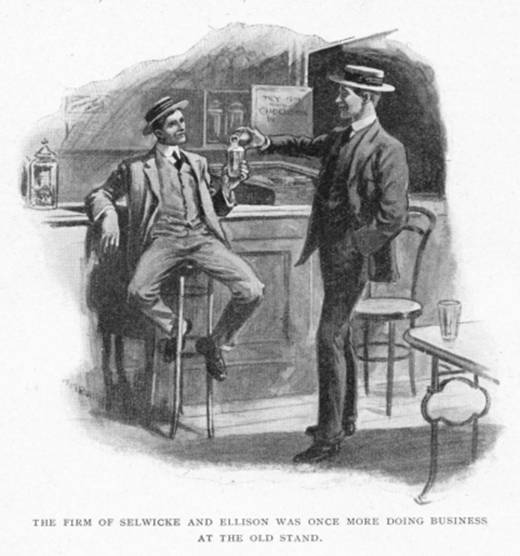

Next day it was noticed by the observant that the firm of Selwicke and Ellison was once more doing business at the old stand.

Note:

Devereux: E. C. Devereux of Eton, supplier of handmade cricket caps and other apparel.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums