The Captain, May 1908

CHAPTER VI.

unpleasantness in the small hours.

ELLICOE, that human encyclopædia,

consulted on the probable movements of the enemy,

deposed that Spiller, retiring at ten, would make

for Dormitory One in the same passage, where Robinson

also had a bed. The rest of the opposing forces

were distributed among other and more distant rooms.

It was probable, therefore, that Dormitory One would

be the rendezvous. As to the time when an attack

might be expected, it was unlikely that it would occur

before half-past eleven. Mr. Outwood went the

round of the dormitories at eleven.

ELLICOE, that human encyclopædia,

consulted on the probable movements of the enemy,

deposed that Spiller, retiring at ten, would make

for Dormitory One in the same passage, where Robinson

also had a bed. The rest of the opposing forces

were distributed among other and more distant rooms.

It was probable, therefore, that Dormitory One would

be the rendezvous. As to the time when an attack

might be expected, it was unlikely that it would occur

before half-past eleven. Mr. Outwood went the

round of the dormitories at eleven.

“And touching,” said Psmith, “the matter of noise, must this business be conducted in a subdued and sotto voce manner, or may we let ourselves go a bit here and there?”

“I shouldn’t think old Outwood’s likely to hear you—he sleeps miles away on the other side of the house. He never hears anything. We often rag half the night and nothing happens.”

“This appears to be a thoroughly nice, well-conducted establishment. What would my mother say if she could see her Rupert in the midst of these reckless youths!”

“All the better,” said Mike; “we don’t want anybody butting in and stopping the show before it’s half started.”

“Comrade Jackson’s Berserk blood is up—I can hear it sizzling. I quite agree: these things are all very disturbing and painful, but it’s as well to do them thoroughly when one’s once in for them. Is there nobody else who might interfere with our gambols?”

“Barnes might,” said Jellicoe, “only he won’t.”

“Who is Barnes?”

“Head of the house—a rotter. He’s in a funk of Stone and Robinson; they rag him; he’ll simply sit tight.”

“Then I think,” said Psmith placidly, “we may look forward to a very pleasant evening. Shall we be moving?”

Mr. Outwood paid his visit at eleven, as predicted by Jellicoe, beaming vaguely into the darkness over a candle, and disappeared again, closing the door.

“How about that door?” said Mike. “Shall we leave it open for them?”

“Not so, but far otherwise. If it’s shut we shall hear them at it when they come. Subject to your approval, Comrade Jackson, I have evolved the following plan of action. I always ask myself on these occasions, ‘What would Napoleon have done?’ I think Napoleon would have sat in a chair by his washhand-stand, which is close to the door; he would have posted you by your washhand-stand, and he would have instructed Comrade Jellicoe, directly he heard the door-handle turned, to give his celebrated imitation of a dormitory breathing heavily in its sleep. He would then——”

“I tell you what,” said Mike, “how about tying a string at the top of the steps?”

“Yes, Napoleon would have done that, too. Hats off to Comrade Jackson, the man with the big brain!”

The floor of the dormitory was below the level of the door. There were three steps leading down to it. Psmith lit a candle and they examined the ground. The leg of a wardrobe and the leg of Jellicoe’s bed made it possible for the string to be fastened in a satisfactory manner across the lower step. Psmith surveyed the result with approval.

“Dashed neat!” he said. “Practically the sunken road which dished the Cuirassiers at Waterloo. I seem to see Comrade Spiller coming one of the finest purlers in the world’s history.”

“If they’ve got a candle——”

“They won’t have. If they have, stand by with your water-jug and douse it at once; then they’ll charge forward and all will be well. If they have no candle, fling the water at a venture—fire into the brown! Lest we forget, I’ll collar Comrade Jellicoe’s jug now and keep it handy. A couple of sheets would also not be amiss—we will enmesh the enemy!”

“Right ho!” said Mike.

“These humane preparations being concluded,” said Psmith, “we will retire to our posts and wait. Comrade Jellicoe, don’t forget to breathe like an asthmatic sheep when you hear the door opened; they may wait at the top of the steps, listening.”

“You are a chap!” said Jellicoe.

Waiting in the dark for something to happen is always a trying experience, especially if, as on this occasion, silence is essential. Mike found his thoughts wandering back to the vigil he had kept with Mr. Wain at Wrykyn on the night when Wyatt had come in through the window and found authority sitting on his bed, waiting for him. Mike was tired after his journey, and he had begun to doze when he was jerked back to wakefulness by the stealthy turning of the door-handle; the faintest rustle from Psmith’s direction followed, and a slight giggle, succeeded by a series of deep breaths, showed that Jellicoe, too, had heard the noise.

There was a creaking sound.

It was pitch dark in the dormitory, but Mike could follow the invaders’ movements as clearly as if it had been broad daylight. They had opened the door and were listening. Jellicoe’s breathing grew more asthmatic; he was flinging himself into his part with the whole-heartedness of the true artist.

The creak was followed by a sound of whispering, then another creak. The enemy had advanced to the top step. . . . Another creak. . . . The vanguard had reached the second step. . . . In another moment——

CRASH!

And at that point the proceedings may be said to have formally opened.

A struggling mass bumped against Mike’s shins as he rose from his chair; he emptied his jug on to this mass, and a yell of anguish showed that the contents had got to the right address.

Then a hand grabbed his ankle and he went down, a million sparks dancing before his eyes as a fist, flying out at a venture, caught him on the nose.

Mike had not been well-disposed towards the invaders before, but now he ran amok, hitting out right and left at random. His right missed, but his left went home hard on some portion of somebody’s anatomy. A kick freed his ankle and he staggered to his feet. At the same moment a sudden increase in the general volume of noise spoke eloquently of good work that was being put in by Psmith.

Even at that crisis, Mike could not help feeling that if a row of this calibre did not draw Mr. Outwood from his bed, he must be an unusual kind of house-master.

He plunged forward again with outstretched arms, and stumbled and fell over one of the on-the-floor section of the opposing force. They seized each other earnestly and rolled across the room till Mike, contriving to secure his adversary’s head, bumped it on the floor with such abandon that, with a muffled yell, the other let go, and for the second time he rose. As he did so he was conscious of a curious thudding sound that made itself heard through the other assorted noises of the battle.

All this time the fight had gone on in the blackest darkness, but now a light shone on the proceedings. Interested occupants of other dormitories, roused from their slumbers, had come to observe the sport. They were crowding in the doorway with a candle.

By the light of this Mike got a swift view of the theatre of war. The enemy appeared to number five. The warrior whose head Mike had bumped on the floor was Robinson, who was sitting up feeling his skull in a gingerly fashion. To Mike’s right, almost touching him, was Stone. In the direction of the door, Psmith, wielding in his right hand the cord of a dressing-gown, was engaging the remaining three with a patient smile. They were clad in pyjamas, and appeared to be feeling the dressing-gown cord acutely.

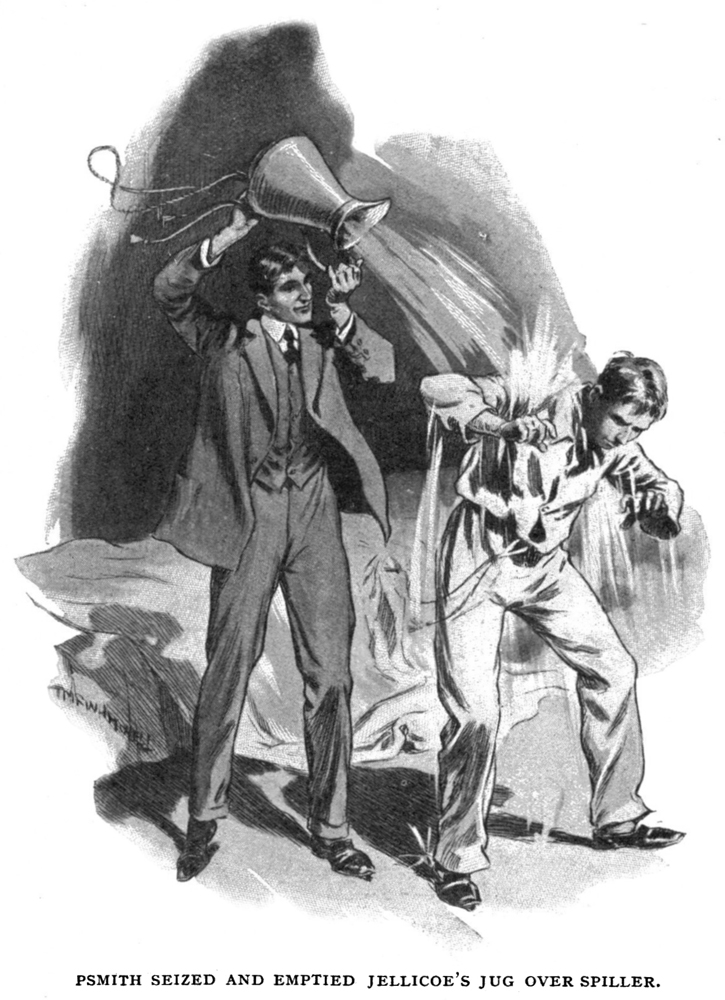

The sudden light dazed both sides

momentarily. The defence was the first to recover,

Mike, with a swing, upsetting Stone, and Psmith, having

seized and emptied Jellicoe’s jug over Spiller,

getting to work again with the cord in a manner that

roused the utmost enthusiasm of the spectators.

The sudden light dazed both sides

momentarily. The defence was the first to recover,

Mike, with a swing, upsetting Stone, and Psmith, having

seized and emptied Jellicoe’s jug over Spiller,

getting to work again with the cord in a manner that

roused the utmost enthusiasm of the spectators.

Agility seemed to be the leading feature of Psmith’s tactics. He was everywhere—on Mike’s bed, on his own, on Jellicoe’s (drawing a passionate complaint from that non-combatant, on whose face he inadvertently trod), on the floor—he ranged the room, sowing destruction.

The enemy were disheartened; they had started with the idea that this was to be a surprise attack, and it was disconcerting to find the garrison armed at all points. Gradually they edged to the door, and a final rush sent them through.

“Hold the door for a second,” cried Psmith, and vanished. Mike was alone in the doorway.

It was a situation which exactly suited his frame of mind; he stood alone in direct opposition to the community into which Fate had pitchforked him so abruptly. He liked the feeling; for the first time since his father had given him his views upon school reports that morning in the Easter holidays, he felt satisfied with life. He hoped, outnumbered as he was, that the enemy would come on again and not give the thing up in disgust; he wanted more.

On an occasion like this there is rarely anything approaching concerted action on the part of the aggressors. When the attack came, it was not a combined attack; Stone, who was nearest to the door, made a sudden dash forward, and Mike hit him under the chin.

Stone drew back, and there was another interval for rest and reflection.

It was interrupted by the reappearance of Psmith, who strolled back along the passage swinging his dressing-gown cord as if it were some clouded cane.

“Sorry to keep you waiting, Comrade Jackson,” he said politely. “Duty called me elsewhere. With the kindly aid of a guide who knows the lie of the land, I have been making a short tour of the dormitories. I have poured divers jugfuls of water over Comrade Spiller’s bed, Comrade Robinson’s bed, Comrade Stone’s—Spiller, Spiller, these are harsh words; where you pick them up I can’t think—not from me. Well, well, I suppose there must be an end to the pleasantest of functions. Good-night, good-night.”

The door closed behind Mike and himself. For ten minutes shufflings and whisperings went on in the corridor, but nobody touched the handle.

Then there was a sound of retreating footsteps, and silence reigned.

On the following morning there was a notice on the house-board. It ran:

INDOOR GAMES.

Dormitory-raiders are informed that in future neither Mr. Psmith nor Mr. Jackson will be at home to visitors. This nuisance must now cease.

R. Psmith.

M. Jackson.

CHAPTER VII.

adair.

N the same morning Mike met Adair for the first time.

N the same morning Mike met Adair for the first time.

He was going across to school with Psmith and Jellicoe, when a group of three came out of the gate of the house next door.

“That’s Adair,” said Jellicoe, “in the middle.”

His voice had assumed a tone almost of awe.

“Who’s Adair?” asked Mike.

“Captain of cricket, and lots of other things.”

Mike could only see the celebrity’s back. He had broad shoulders and wiry, light hair, almost white. He walked well, as if he were used to running. Altogether a fit-looking sort of man. Even Mike’s jaundiced eye saw that.

As a matter of fact, Adair deserved more than a casual glance. He was that rare type, the natural leader. Many boys and men, if accident, or the passage of time, places them in a position where they are expected to lead, can handle the job without disaster; but that is a very different thing from being a born leader. Adair was of the sort that comes to the top by sheer force of character and determination. He was not naturally clever at work, but he had gone at it with a dogged resolution which had carried him up the school, and landed him high in the Sixth. As a cricketer he was almost entirely self-taught. Nature had given him a good eye, and left the thing at that. Adair’s doggedness had triumphed over her failure to do her work thoroughly. At the cost of more trouble than most people give to their life-work he had made himself into a bowler. He read the authorities, and watched first-class players, and thought the thing out on his own account, and he divided the art of bowling into three sections. First, and most important—pitch. Second on the list—break. Third—pace. He set himself to acquire pitch. He acquired it. Bowling at his own pace and without any attempt at break, he could now drop the ball on an envelope seven times out of ten.

Break was a more uncertain quantity. Sometimes he could get it at the expense of pitch, sometimes at the expense of pace. Some days he could get all three, and then he was an uncommonly bad man to face on anything but a plumb wicket.

Running he had acquired in a similar manner. He had nothing approaching style, but he had twice won the mile and half-mile at the Sports off elegant runners, who knew all about stride and the correct timing of the sprints and all the rest of it.

Briefly, he was a worker. He had heart.

A boy of Adair’s type is always a force in a school. In a big public school of six or seven hundred, his influence is felt less; but in a small school like Sedleigh he is like a tidal wave, sweeping all before him. There were two hundred boys at Sedleigh, and there was not one of them in all probability who had not, directly or indirectly, been influenced by Adair. As a small boy his sphere was not large, but the effects of his work began to be apparent even then. It is human nature to want to get something which somebody else obviously values very much; and when it was observed by members of his form that Adair was going to great trouble and inconvenience to secure a place in the form eleven or fifteen, they naturally began to think, too, that it was worth being in those teams. The consequence was that his form always played hard. This made other forms play hard. And the net result was that, when Adair succeeded to the captaincy of football and cricket in the same year, Sedleigh, as Mr. Downing, Adair’s house-master and the nearest approach to a cricket master that Sedleigh possessed, had a fondness for saying, was a keen school. As a whole, it both worked and played with energy.

All it wanted now was opportunity.

This Adair was determined to give it. He had that passionate fondness for his school which every boy is popularly supposed to have, but which really is implanted in about one in every thousand. The average public-school boy likes his school. He hopes it will lick Bedford at footer and Malvern at cricket, but he rather bets it won’t. He is sorry to leave, and he likes going back at the end of the holidays, but as for any passionate, deep-seated love of the place, he would think it rather bad form than otherwise. If anybody came up to him, slapped him on the back, and cried, “Come along, Jenkins, my boy! Play up for the old school, Jenkins! The dear old school! The old place you love so!” he would feel seriously ill.

Adair was the exception.

To Adair, Sedleigh was almost a religion. Both his parents were dead; his guardian, with whom he spent the holidays, was a man with neuralgia at one end of him and gout at the other; and the only really pleasant times Adair had had, as far back as he could remember, he owed to Sedleigh. The place had grown on him, absorbed him. Where Mike, violently transplanted from Wrykyn, saw only a wretched little hole not to be mentioned in the same breath with Wrykyn, Adair, dreaming of the future, saw a colossal establishment, a public school among public schools, a lump of human radium, shooting out Blues and Balliol Scholars year after year without ceasing.

It would not be so till long after he was gone and forgotten, but he did not mind that. His devotion to Sedleigh was purely unselfish. He did not want fame. All he worked for was that the school should grow and grow, keener and better at games and more prosperous year by year, till it should take its rank among the schools, and to be an Old Sedleighan should be a badge passing its owner everywhere.

“He’s captain of cricket and footer,” said Jellicoe impressively. “He’s in the shooting eight. He’s won the mile and half two years running. He would have boxed at Aldershot last term, only he sprained his wrist. And he plays fives jolly well!”

“Sort of little tin god,” said Mike, taking a violent dislike to Adair from that moment.

Mike’s actual acquaintance with this all-round man dated from the dinner-hour that day. Mike was walking to the house with Psmith. Psmith was a little ruffled on account of a slight passage-of-arms he had had with his form-master during morning school.

“ ‘There’s a P before the Smith,’ I said to him. ‘Ah, P. Smith, I see,’ replied the goat. ‘Not Peasmith,’ I replied, exercising wonderful self-restraint, ‘just Psmith.’ It took me ten minutes to drive the thing into the man’s head; and when I had driven it in, he sent me out of the room for looking at him through my eye-glass. Comrade Jackson, I fear me we have fallen among bad men. I suspect that we are going to be much persecuted by scoundrels.”

“Both you chaps play cricket, I suppose?”

They turned. It was Adair. Seeing him face to face, Mike was aware of a pair of very bright blue eyes and a square jaw. In any other place and mood he would have liked Adair at sight. His prejudice, however, against all things Sedleighan was too much for him. “I don’t,” he said shortly.

“Haven’t you ever played?”

“My little sister and I sometimes play with a soft ball at home.”

Adair looked sharply at him. A temper was evidently one of his numerous qualities.

“Oh,” he said. “Well, perhaps you wouldn’t mind turning out this afternoon and seeing what you can do with a hard ball—if you can manage without your little sister.”

“I should think the form at this place would be about on a level with hers. But I don’t happen to be playing cricket, as I think I told you.”

Adair’s jaw grew squarer than ever. Mike was wearing a gloomy scowl.

Psmith joined suavely in the dialogue.

“My dear old comrades,” he said, “don’t let us brawl over this matter. This is a time for the honeyed word, the kindly eye, and the pleasant smile. Let me explain to Comrade Adair. Speaking for Comrade Jackson and myself, we should both be delighted to join in the mimic warfare of our National Game, as you suggest, only the fact is, we happen to be the Young Archæologists. We gave in our names last night. When you are being carried back to the pavilion after your century against Loamshire—do you play Loamshire?—we shall be grubbing in the hard ground for ruined abbeys. The old choice between Pleasure and Duty, Comrade Adair. A Boy’s Cross-Roads.”

“Then you won’t play?”

“No,” said Mike.

“Archæology,” said Psmith, with a deprecatory wave of the hand, “will brook no divided allegiance from her devotees.”

Adair turned, and walked on.

Scarcely had he gone, when another voice hailed them with precisely the same question.

“Both you fellows are going to play cricket, eh?”

It was a master. A short, wiry little man with a sharp nose and a general resemblance, both in manner and appearance, to an excitable bullfinch.

“I saw Adair speaking to you. I suppose you will both play. I like every new boy to begin at once. The more new blood we have, the better. We want keenness here. We are, above all, a keen school. I want every boy to be keen.”

“We are, sir,” said Psmith, with fervour.

“Excellent.”

“On archæology.”

Mr. Downing—for it was no less a celebrity—started, as one who perceives a loathly caterpillar in his salad.

“Archæology!”

“We gave in our names to Mr. Outwood last night, sir. Archæology is a passion with us, sir. When we heard that there was a society here, we went singing about the house.”

“I call it an unnatural pursuit for boys,” said Mr. Downing vehemently. “I don’t like it. I tell you I don’t like it. It is not for me to interfere with one of my colleagues on the staff, but I tell you frankly that in my opinion it is an abominable waste of time for a boy. It gets him into idle, loafing habits.”

“I never loaf, sir,” said Psmith.

“I was not alluding to you in particular. I was referring to the principle of the thing. A boy ought to be playing cricket with other boys, not wandering at large about the country, probably smoking and going into low public-houses.”

“A very wild lot, sir, I fear, the Archæological Society here,” sighed Psmith, shaking his head.

“If you choose to waste your time, I suppose I can’t hinder you. But in my opinion it is foolery, nothing else.”

He stumped off.

“Now he’s cross,” said Psmith, looking after him. “I’m afraid we’re getting ourselves disliked here.”

“Good job, too.”

“At any rate, Comrade Outwood loves us. Let’s go on and see what sort of a lunch that large-hearted fossil-fancier is going to give us.”

CHAPTER VIII.

mike finds occupation.

HERE was more than one moment during

the first fortnight of term when Mike found himself

regretting the attitude he had imposed upon himself

with regard to Sedleighan cricket. He began to

realise the eternal truth of the proverb about half

a loaf and no bread. In the first flush of his

resentment against his new surroundings he had refused

to play cricket. And now he positively ached

for a game. Any sort of a game. An innings

for a Kindergarten v. the Second Eleven of a

Home of Rest for Centenarians would have soothed him.

There were times, when the sun shone, and he caught

sight of white flannels on a green ground, and heard

the “plonk” of bat striking ball, when

he felt like rushing to Adair and shouting, “I

will be good. I was in the Wrykyn team

three years, and had an average of over fifty the last

two seasons. Lead me to the nearest net, and let

me feel a bat in my hands again.”

HERE was more than one moment during

the first fortnight of term when Mike found himself

regretting the attitude he had imposed upon himself

with regard to Sedleighan cricket. He began to

realise the eternal truth of the proverb about half

a loaf and no bread. In the first flush of his

resentment against his new surroundings he had refused

to play cricket. And now he positively ached

for a game. Any sort of a game. An innings

for a Kindergarten v. the Second Eleven of a

Home of Rest for Centenarians would have soothed him.

There were times, when the sun shone, and he caught

sight of white flannels on a green ground, and heard

the “plonk” of bat striking ball, when

he felt like rushing to Adair and shouting, “I

will be good. I was in the Wrykyn team

three years, and had an average of over fifty the last

two seasons. Lead me to the nearest net, and let

me feel a bat in my hands again.”

But every time he shrank from such a climb down. It couldn’t be done.

What made it worse was that he saw, after watching behind the nets once or twice, that Sedleigh cricket was not the childish burlesque of the game which he had been rash enough to assume that it must be. Numbers do not make good cricket. They only make the presence of good cricketers more likely, by the law of averages.

Mike soon saw that cricket was by no means an unknown art at Sedleigh. Adair, to begin with, was a very good bowler indeed. He was not a Burgess, but Burgess was the only Wrykyn bowler whom, in his three years’ experience of the school, Mike would have placed above him. He was a long way better than Neville-Smith, and Wyatt, and Milton, and the others who had taken wickets for Wrykyn.

The batting was not so good, but there were some quite capable men. Barnes, the head of Outwood’s, he who preferred not to interfere with Stone and Robinson, was a mild, rather timid-looking youth—not unlike what Mr. Outwood must have been as a boy—but he knew how to keep balls out of his wicket. He was a good bat of the old plodding type.

Stone and Robinson themselves, that swash-buckling pair, who now treated Mike and Psmith with cold but consistent politeness, were both fair batsmen, and Stone was a good slow bowler.

There were other exponents of the game, mostly in Downing’s house.

Altogether, quite worthy colleagues even for a man who had been a star at Wrykyn.

One solitary overture Mike made during that first fortnight. He did not repeat the experiment. It was on a Thursday afternoon, after school. The day was warm, but freshened by an almost imperceptible breeze. The air was full of the scent of the cut grass which lay in little heaps behind the nets. This is the real cricket scent, which calls to one like the very voice of the game.

Mike, as he sat there watching, could stand it no longer.

He went up to Adair.

“May I have an innings at this net?” he asked. He was embarrassed and nervous, and was trying not to show it. The natural result was that his manner was offensively abrupt.

Adair was taking off his pads after his innings. He looked up. “This net,” it may be observed, was the first eleven net.

“What?” he said.

Mike repeated his request. More abruptly this time, from increased embarrassment.

“This is the first eleven net,” said Adair coldly. “Go in after Lodge over there.”

“Over there” was the end net, where frenzied novices were bowling on a corrugated pitch to a red-haired youth with enormous feet, who looked as if he were taking his first lesson at the game.

Mike walked away without a word.

The Archæological Society expeditions, even though they carried with them the privilege of listening to Psmith’s views on life, proved but a poor substitute for cricket. Psmith, who had no counter attraction shouting to him that he ought to be elsewhere, seemed to enjoy them hugely, but Mike almost cried sometimes from boredom. It was not always possible to slip away from the throng, for Mr. Outwood evidently looked upon them as among the very faithful, and kept them by his aide.

Mike on these occasions was silent and jumpy, his brow “sicklied o’er with the pale cast of care.” But Psmith followed his leader with the pleased and indulgent air of a father whose infant son is showing him round the garden. Psmith’s attitude towards archæological research struck a new note in the history of that neglected science. He was amiable, but patronising. He patronised fossils, and he patronised ruins. If he had been confronted with the Great Pyramid, he would have patronised that.

He seemed to be consumed by a thirst for knowledge.

That this was not altogether a genuine thirst was proved on the third expedition. Mr. Outwood and his band were pecking away at the site of an old Roman camp. Psmith approached Mike.

“Having inspired confidence,” he said, “by the docility of our demeanour, let us slip away, and brood apart for awhile. Roman camps, to be absolutely accurate, give me the pip. And I never want to see another putrid fossil in my life. Let us find some shady nook where a man may lie on his back for a bit.”

Mike, over whom the proceedings connected with the Roman camp had long since begun to shed a blue depression, offered no opposition, and they strolled away down the hill.

Looking back, they saw that the archæologists were still hard at it. Their departure had passed unnoticed.

“A fatiguing pursuit, this grubbing for mementoes of the past,” said Psmith. “And, above all, dashed bad for the knees of the trousers. Mine are like some furrowed field. It’s a great grief to a man of refinement, I can tell you, Comrade Jackson. Ah, this looks a likely spot.”

They had passed through a gate into the field beyond. At the further end there was a brook, shaded by trees and running with a pleasant sound over pebbles.

“Thus far,” said Psmith, hitching up the knees of his trousers, and sitting down, “and no farther. We will rest here awhile, and listen to the music of the brook. In fact, unless you have anything important to say, I rather think I’ll go to sleep. In this busy life of ours these naps by the wayside are invaluable. Call me in about an hour.” And Psmith, heaving the comfortable sigh of the worker who by toil has earned rest, lay down, with his head against a mossy tree stump, and closed his eyes.

Mike sat on for a few minutes, listening to the water and making centuries in his mind, and then, finding this a little dull, he got up, jumped the brook, and began to explore the wood on the other side.

He had not gone many yards when a dog emerged suddenly from the undergrowth, and began to bark vigorously at him.

Mike liked dogs, and, on acquaintance, they always liked him. But when you meet a dog in some one else’s wood, it is as well not to stop in order that you may get to understand each other. Mike began to thread his way back through the trees.

He was too late.

“Stop! What the dickens are you doing here?” shouted a voice behind him.

In the same situation a few years before, Mike would have carried on, and trusted to speed to save him. But now there seemed a lack of dignity in the action. He came back to where the man was standing.

“I’m sorry if I’m trespassing,” he said. “I was just having a look round.”

“The dickens you— Why, you’re Jackson!”

Mike looked at him. He was a short, broad young man with a fair moustache. Mike knew that he had seen him before somewhere, but he could not place him.

“I played against you for the Free Foresters last summer. In passing, you seem to be a bit of a free forester yourself, dancing in among my nesting pheasants.”

“I’m frightfully sorry.”

“That’s all right. Where do you spring from?”

“Of course—I remember you now. You’re Prendergast. You made fifty-eight not out.”

“Thanks. I was afraid the only thing you would remember about me was that you took a century mostly off my bowling.”

“You ought to have had me second ball, only cover dropped it.”

“Don’t rake up forgotten tragedies. How is it you’re not at Wrykyn? What are you doing down here?”

“I’ve left Wrykyn.”

Prendergast suddenly changed the conversation. When a fellow tells you that he has left school unexpectedly, it is not always tactful to inquire the reason. He began to talk about himself.

“I hang out down here. I do a little farming and a good deal of pottering about.”

“Get any cricket?” asked Mike, turning to the subject next his heart.

“Only village. Very keen, but no great shakes. By the way, how are you off for cricket now? Have you ever got a spare afternoon?”

Mike’s heart leaped.

“Any Wednesday or Saturday. Look here, I’ll tell you how it is.”

And he told how matters stood with him.

“So, you see,” he concluded, “I’m supposed to be hunting for ruins and things”—Mike’s ideas on the subject of archæology were vague—“but I could always slip away. We all start out together, but I could nip back, get on to my bike—I’ve got it down here—and meet you anywhere you liked. By Jove, I’m simply dying for a game. I can hardly keep my hands off a bat.”

“I’ll give you all you want. What you’d better do is to ride straight to Lower Borlock—that’s the name of the place—and I’ll meet you on the ground. Any one will tell you where Lower Borlock is. It’s just off the London road. There’s a sign-post where you turn off. Can you come next Saturday?”

“Rather. I suppose you can fix me up with a bat and pads? I don’t want to bring mine.”

“I’ll lend you everything. I say, you know, we can’t give you a Wrykyn wicket. The Lower Borlock pitch isn’t a shirt-front.”

“I’ll play on a rockery, if you want me to,” said Mike.

“You’re going to what?” asked Psmith, sleepily, on being awakened and told the news.

“I’m going to play cricket, for a village near here. I say, don’t tell a soul, will you? I don’t want it to get about, or I may get lugged in to play for the school.”

“My lips are sealed. I think I’ll come and watch you. Cricket I dislike, but watching cricket is one of the finest of Britain’s manly sports. I’ll borrow Jellicoe’s bicycle.”

That Saturday, Lower Borlock smote the men of Chidford hip and thigh. Their victory was due to a hurricane innings of seventy-five by a newcomer to the team, M. Jackson.

CHAPTER IX.

the fire brigade meeting.

RICKET is the great safety-valve.

If you like the game, and are in a position to play

it at least twice a week, life can never be entirely

grey. As time went on, and his average for Lower

Borlock reached the fifties and stayed there, Mike

began, though he would not have admitted it, to enjoy

himself. It was not Wrykyn, but it was a very

decent substitute.

RICKET is the great safety-valve.

If you like the game, and are in a position to play

it at least twice a week, life can never be entirely

grey. As time went on, and his average for Lower

Borlock reached the fifties and stayed there, Mike

began, though he would not have admitted it, to enjoy

himself. It was not Wrykyn, but it was a very

decent substitute.

The only really considerable element making for discomfort now was Mr. Downing. By bad luck it was in his form that Mike had been placed on arrival; and Mr. Downing, never an easy form master to get on with, proved more than usually difficult in his dealings with Mike.

They had taken a dislike to each other at their first meeting; and it grew with further acquaintance. To Mike, Mr. Downing was all that a master ought not to be, fussy, pompous, and openly influenced in his official dealings with his form by his own private likes and dislikes. To Mr. Downing, Mike was simply an unamiable loafer, who did nothing for the school and apparently had none of the instincts which should be implanted in the healthy boy. Mr. Downing was rather strong on the healthy boy.

The two lived in a state of simmering hostility, punctuated at intervals by crises, which usually resulted in Lower Borlock having to play some unskilled labourer in place of their star batsman, employed doing “overtime.”

One of the most acute of these crises, and the most important, in that it was the direct cause of Mike’s appearance in Sedleigh cricket, had to do with the third weekly meeting of the School Fire Brigade.

It may be remembered that this well-supported institution was under Mr. Downing’s special care. It was, indeed, his pet hobby and the apple of his eye.

Just as you had to join the Archæological Society to secure the esteem of Mr. Outwood, so to become a member of the Fire Brigade was a safe passport to the regard of Mr. Downing. To show a keenness for cricket was good, but to join the Fire Brigade was best of all. The Brigade was carefully organised. At its head was Mr. Downing, a sort of high priest; under him was a captain, and under the captain a vice-captain. These two officials were those sportive allies, Stone and Robinson, of Outwood’s house, who, having perceived at a very early date the gorgeous opportunities for ragging which the Brigade offered to its members, had joined young and worked their way up.

Under them were the rank and file, about thirty in all, of whom perhaps seven were earnest workers, who looked on the Brigade in the right, or Downing, spirit. The rest were entirely frivolous.

The weekly meetings were always full of life and excitement.

At this point it is as well to introduce Sammy to the reader.

Sammy, short for Sampson, was a young bull-terrier belonging to Mr. Downing. If it is possible for a man to have two apples of his eye, Sammy was the other. He was a large, light-hearted dog with a white coat, an engaging expression, the tongue of an ant-eater, and a manner which was a happy blend of hurricane and circular saw. He had long legs, a tenor voice, and was apparently made of indiarubber.

Sammy was a great favourite in the school, and a particular friend of Mike’s, the Wrykynian being always a firm ally of every dog he met after two minutes’ acquaintance.

In passing, Jellicoe owned a clock-work rat, much in request during French lessons.

We will now proceed to the painful details.

The meetings of the Fire Brigade were held after school in Mr. Downing’s form-room. The proceedings always began in the same way, by the reading of the minutes of the last meeting. After that the entertainment varied according to whether the members happened to be fertile or not in ideas for the disturbing of the peace.

To-day they were in very fair form.

As soon as Mr. Downing had closed the minute-book, Wilson, of the School House, held up his hand.

“Well, Wilson?”

“Please, sir, couldn’t we have a uniform for the Brigade?”

“A uniform?” Mr. Downing pondered.

“Red, with green stripes, sir.”

Red, with a thin green stripe, was the Sedleigh colour.

“Shall I put it to the vote, sir?” asked Stone.

“One moment, Stone.”

“Those in favour of the motion move to the left, those against it to the right.”

A scuffling of feet, a slamming of desk-lids and an upset blackboard, and the meeting had divided.

Mr. Downing rapped irritably on his desk.

“Sit down!” he said, “sit down! I won’t have this noise and disturbance. Stone, sit down—Wilson, get back to your place.”

“Please, sir, the motion is carried by twenty-five votes to six.”

“Please, sir, may I go and get measured this evening?”

“Please, sir——”

“Si-lence! The idea of a uniform is, of course, out of the question.”

“Oo-o-oo-oo, sir-r-r!”

“Be quiet! Entirely out of the question. We cannot plunge into needless expense. Stone, listen to me. I cannot have this noise and disturbance! Another time when a point arises it must be settled by a show of hands. Well, Wilson?”

“Please, sir, may we have helmets?”

“Very useful as a protection against falling timbers, sir,” said Robinson.

“I don’t think my people would be pleased, sir, if they knew I was going out to fires without a helmet,” said Stone.

The whole strength of the company: “Please, sir, may we have helmets?”

“Those in favour——” began Stone.

Mr. Downing banged on his desk. “Silence! Silence!! Silence!!! Helmets are, of course, perfectly preposterous.”

“Oo-oo-oo-oo, sir-r-r!”

“But, sir, the danger!”

“Please, sir, the falling timbers!”

The Fire Brigade had been in action once and once only in the memory of man, and that time it was a haystack which had burnt itself out just as the rescuers had succeeded in fastening the hose to the hydrant.

“Silence!”

“Then, please, sir, couldn’t we have an honour cap? It wouldn’t be expensive, and it would be just as good as a helmet for all the timbers that are likely to fall on our heads.”

Mr. Downing smiled a wry smile.

“Our Wilson is facetious,” he remarked frostily.

“Sir, no, sir! I wasn’t facetious! Or couldn’t we have footer-tops, like the first fifteen have? They——”

“Wilson, leave the room!”

“Sir, please, sir!”

“This moment, Wilson. And,” as he reached the door, “do me one hundred lines.”

A pained “OO-oo-oo, sir-r-r,” was cut off by the closing door.

Mr. Downing proceeded to improve the occasion. “I deplore this growing spirit of flippancy,” he said. “I tell you I deplore it! It is not right! If this Fire Brigade is to be of solid use, there must be less of this flippancy. We must have keenness. I want you boys above all to be keen. I— What is that noise?”

From the other side of the door proceeded a sound like water gurgling from a bottle, mingled with cries half-suppressed, as if somebody were being prevented from uttering them by a hand laid over his mouth. The sufferer appeared to have a high voice.

There was a tap at the door and Mike walked in. He was not alone. Those near enough to see, saw that he was accompanied by Jellicoe’s clock-work rat, which moved rapidly over the floor in the direction of the opposite wall.

“May I fetch a book from my desk, sir?” asked Mike.

“Very well—be quick, Jackson; we are busy.”

Being interrupted in one of his addresses to the Brigade irritated Mr. Downing.

The muffled cries grew more distinct.

“What—is—that—noise?” shrilled Mr. Downing.

“Noise, sir?” asked Mike, puzzled.

“I think it’s something outside the window, sir,” said Stone, helpfully.

“A bird, I think, sir,” said Robinson.

“Don’t be absurd!” snapped Mr. Downing. “It’s outside the door. Wilson!”

“Yes, sir?” said a voice “off.”

“Are you making that whining noise?”

“Whining noise, sir? No, sir, I’m not making a whining noise.”

“What sort of noise, sir?” inquired Mike, as many Wrykynians had asked before him. It was a question invented by Wrykyn for use in just such a case as this.

“I do not propose,” said Mr. Downing acidly, “to imitate the noise; you can all hear it perfectly plainly. It is a curious whining noise.”

“They are mowing the cricket field, sir,” said the invisible Wilson. “Perhaps that’s it.”

“It may be one of the desks squeaking, sir,” put in Stone. “They do sometimes.”

“Or somebody’s boots, sir,” added Robinson.

“Silence! Wilson?”

“Yes, sir?” bellowed the unseen one.

“Don’t shout at me from the corridor like that. Come in.”

“Yes, sir!”

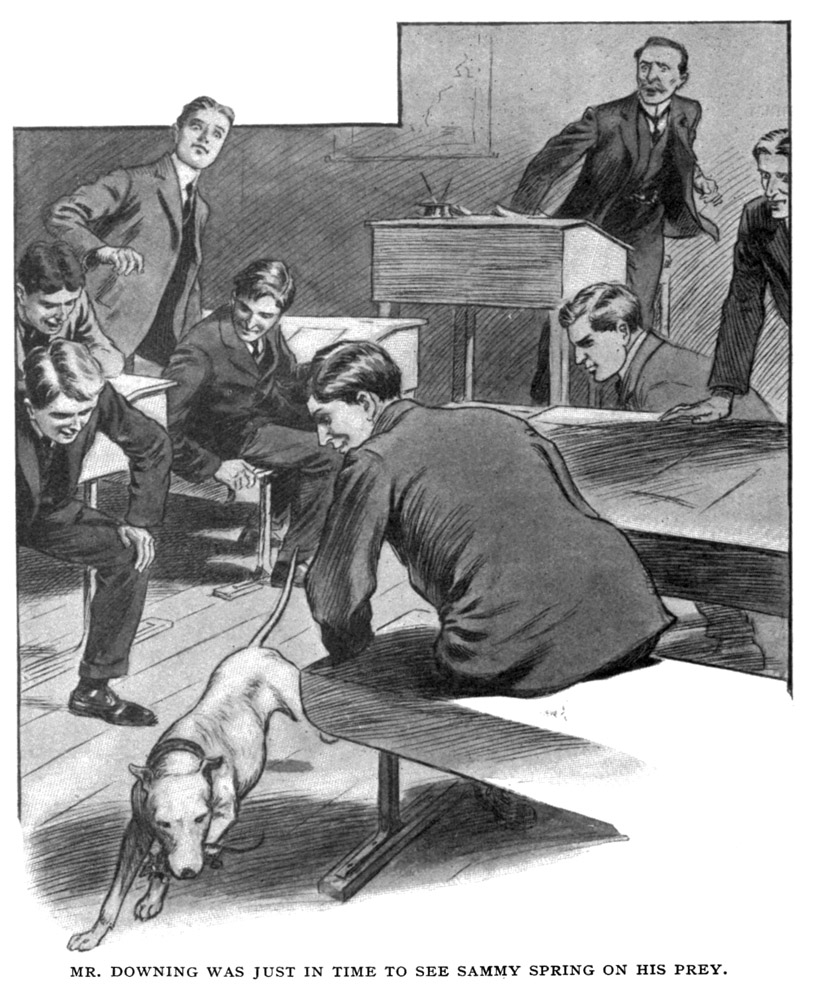

As he spoke the muffled whining changed suddenly to a series of tenor shrieks, and the indiarubber form of Sammy bounded into the room like an excited kangaroo.

Willing hands had by this time deflected the clock-work rat from the wall to which it had been steering, and pointed it up the alley-way between the two rows of desks. Mr. Downing, rising from his place, was just in time to see Sammy with a last leap spring on his prey and begin worrying it.

Chaos reigned.

“A rat!” shouted Robinson.

The twenty-three members of the Brigade who were not earnest instantly dealt with the situation, each in the manner that seemed proper to him. Some leaped on to forms, others flung books, all shouted. It was a stirring, bustling scene.

Sammy had by this time disposed of the clock-work rat, and was now standing, like Marius, among the ruins barking triumphantly.

The banging on Mr. Downing’s desk resembled thunder. It rose above all the other noises till in time they gave up the competition and died away.

Mr. Downing shot out orders, threats, and penalties with the rapidity of a Maxim gun.

“Stone, sit down! Donovan, if you do not sit down, you will be severely punished. Henderson, one hundred lines for gross disorder! Windham, the same! Go to your seat, Vincent. What are you doing, Boughton-Knight? I will not have this disgraceful noise and disorder! The meeting is at an end; go quietly from the room, all of you. Jackson and Wilson, remain. Quietly, I said, Durand! Don’t shuffle your feet in that abominable way.”

Crash!

“Wolferstan, I distinctly saw you upset that blackboard with a movement of your hand—one hundred lines. Go quietly from the room, everybody.”

The meeting dispersed.

“Jackson and Wilson, come here. What’s the meaning of this disgraceful conduct? Put that dog out of the room, Jackson.”

Mike removed the yelling Sammy and shut the door on him.

“Well, Wilson?”

“Please, sir, I was playing with a clock-work rat——”

“What business have you to be playing with clock-work rats?”

“Then I remembered,” said Mike, “that I had left my Horace in my desk, so I came in——”

“And by a fluke, sir,” said Wilson, as one who tells of strange things, “the rat happened to be pointing in the same direction, so he came in, too.”

“I met Sammy on the gravel outside and he followed me.”

“I tried to collar him, but when you told me to come in, sir, I had to let him go, and he came in after the rat.”

It was plain to Mr. Downing that the burden of sin was shared equally by both culprits. Wilson had supplied the rat, Mike the dog; but Mr. Downing liked Wilson and disliked Mike. Wilson was in the Fire Brigade, frivolous at times, it was true, but nevertheless a member. Also he kept wicket for the school. Mike was a member of the Archæological Society, and had refused to play cricket.

Mr. Downing allowed these facts to influence him in passing sentence.

“One hundred lines, Wilson,” he said. “You may go.”

Wilson departed with the air of a man who has had a great deal of fun, and paid very little for it.

Mr. Downing turned to Mike. “You will stay in on Saturday afternoon, Jackson; it will interfere with your Archæological studies, I fear, but it may teach you that we have no room at Sedleigh for boys who spend their time loafing about and making themselves a nuisance. We are a keen school; this is no place for boys who do nothing but waste their time. That will do, Jackson.”

And Mr. Downing walked out of the room. In affairs of this kind a master has a habit of getting the last word.

CHAPTER X.

achilles leaves his tent.

HEY say misfortunes never come singly.

As Mike sat brooding over his wrongs in his study,

after the Sammy incident, Jellicoe came into the room,

and, without preamble, asked for the loan of a sovereign.

HEY say misfortunes never come singly.

As Mike sat brooding over his wrongs in his study,

after the Sammy incident, Jellicoe came into the room,

and, without preamble, asked for the loan of a sovereign.

When one has been in the habit of confining one’s lendings and borrowings to sixpences and shillings, a request for a sovereign comes as something of a blow.

“What on earth for?” asked Mike.

“I say, do you mind if I don’t tell you? I don’t want to tell anybody. The fact is, I’m in a beastly hole.”

“Oh, sorry,” said Mike. “As a matter of fact, I do happen to have a quid. You can freeze on to it, if you like. But it’s about all I have got, so don’t be shy about paying it back.”

Jellicoe was profuse in his thanks, and disappeared in a cloud of gratitude.

Mike felt that Fate was treating him badly. Being kept in on Saturday meant that he would be unable to turn out for Little Borlock against Claythorpe, the return match. In the previous game he had scored ninety-eight, and there was a lob bowler in the Claythorpe ranks whom he was particularly anxious to meet again. Having to yield a sovereign to Jellicoe—why on earth did the man want all that?—meant that, unless a carefully worded letter to his brother Bob at Oxford had the desired effect, he would be practically penniless for weeks.

In a gloomy frame of mind he sat down to write to Bob, who was playing regularly for the ’Varsity this season, and only the previous week had made a century against Sussex, so might be expected to be in a sufficiently softened mood to advance the needful. (Which, it may be stated at once, he did, by return of post.)

Mike was struggling with the opening sentences of this letter—he was never a very ready writer—when Stone and Robinson burst into the room.

Mike put down his pen, and got up. He was in warlike mood, and welcomed the intrusion. If Stone and Robinson wanted battle, they should have it.

But the motives of the expedition were obviously friendly. Stone beamed. Robinson was laughing.

“You’re a sportsman,” said Robinson.

“What did he give you?” asked Stone.

They sat down, Robinson on the table, Stone in Psmith’s deck-chair. Mike’s heart warmed to them. The little disturbance in the dormitory was a thing of the past, done with, forgotten, contemporary with Julius Cæsar. He felt that he, Stone and Robinson must learn to know and appreciate one another.

There was, as a matter of fact, nothing much wrong with Stone and Robinson. They were just ordinary raggers of the type found at every public school, small and large. They were absolutely free from brain. They had a certain amount of muscle, and a vast store of animal spirits. They looked on school life purely as a vehicle for ragging. The Stones and Robinsons are the swashbucklers of the school world. They go about, loud and boisterous, with a whole-hearted and cheerful indifference to other people’s feelings, treading on the toes of their neighbour and shoving him off the pavement, and always with an eye wide open for any adventure. As to the kind of adventure, they are not particular so long as it promises excitement. Sometimes they go through their whole school career without accident. More often they run up against a snag in the shape of some serious-minded and muscular person who objects to having his toes trodden on and being shoved off the pavement, and then they usually sober down, to the mutual advantage of themselves and the rest of the community.

One’s opinion of this type of youth varies according to one’s point of view. Small boys whom they had occasion to kick, either from pure high spirits or as a punishment for some slip from the narrow path which the ideal small boy should tread, regarded Stone and Robinson as bullies of the genuine “Eric” and “St. Winifred’s” brand. Masters were rather afraid of them. Adair had a smouldering dislike for them. They were useful at cricket, but apt not to take Sedleigh as seriously as he could have wished.

As for Mike, he now found them pleasant company, and began to get out the tea-things.

“Those Fire Brigade meetings,” said Stone, “are a rag. You can do what you like, and you never get more than a hundred lines.”

“Don’t you!” said Mike. “I got Saturday afternoon.”

“What!”

“Is Wilson in too?”

“No. He got a hundred lines.”

Stone and Robinson were quite concerned.

“What a beastly swindle!”

“That’s because you don’t play cricket. Old Downing lets you do what you like if you join the Fire Brigade and play cricket.”

“ ‘We are above all a keen school,’ ” quoted Stone. “Don’t you ever play?”

“I have played a bit,” said Mike.

“Well, why don’t you have a shot? We aren’t such flyers here. If you know one end of a bat from the other, you could get into some sort of a team. Were you at school anywhere before you came here?”

“I was at Wrykyn.”

“Why on earth did you leave?” asked Stone. “Were you sacked?”

“No. My pater took me away.”

“Wrykyn?” said Robinson. “Are you any relation of the Jacksons there—J. W. and the others?”

“Brother.”

“What!”

“Well, didn’t you play at all there?”

“Yes,” said Mike, “I did. I was in the team three years, and I should have been captain this year, if I’d stopped on.”

There was a profound and gratifying sensation. Stone gaped, and Robinson nearly dropped his tea-cup.

Stone broke the silence.

“But I mean to say—look here! What I mean is, why aren’t you playing? Why don’t you play now?”

“I do. I play for a village near here. Place called Little Borlock. A man who played against Wrykyn for the Free Foresters captains them. He asked me if I’d like some games for them.”

“But why not for the school?”

“Why should I? It’s much better fun for the village. You don’t get ordered about by Adair, for a start.”

“Adair sticks on side,” said Stone.

“Enough for six,” agreed Robinson.

“By Jove,” said Stone, “I’ve got an idea. My word, what a rag!”

“What’s wrong now?” inquired Mike politely.

“Why, look here. To-morrow’s Mid-term Service day. It’s nowhere near the middle of the term, but they always have it in the fourth week. There’s chapel at half-past nine till half-past ten. Then the rest of the day’s a whole holiday. There are always house matches. We’re playing Downing’s. Why don’t you play and let’s smash them?”

“By Jove, yes,” said Robinson. “Why don’t you? They’re always sticking on side because they’ve won the house cup three years running. I say, do you bat or bowl?”

“Bat. Why?”

Robinson rocked on the table.

“Why, old Downing fancies himself as a bowler. You must play, and knock the cover off him.”

“Masters don’t play in house matches, surely?”

“This isn’t a real house match. Only a friendly. Downing always turns out on Mid-term Service day. I say, do play.”

“Think of the rag.”

“But the team’s full,” said Mike.

“The list isn’t up yet. We’ll nip across to Barnes’ study, and make him alter it.”

They dashed out of the room. From down the passage Mike heard yells of “Barnes!” the closing of a door, and a murmur of excited conversation. Then footsteps returning down the passage.

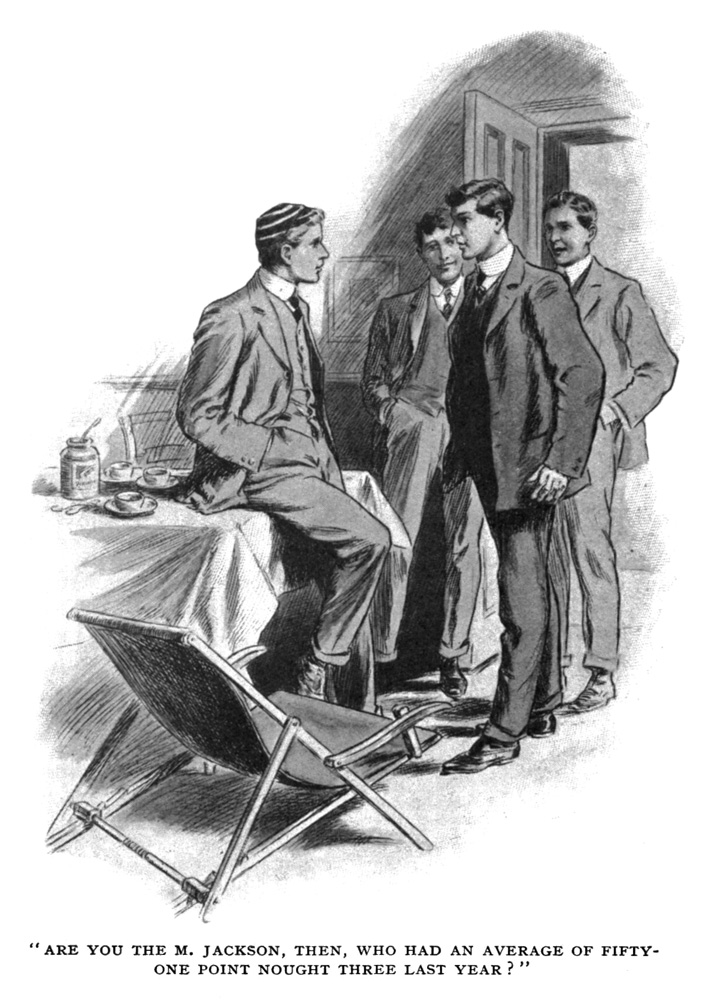

Barnes appeared, on his face the look of one who has seen visions.

“I say,” he said, “is it true? Or is Stone rotting? About Wrykyn, I mean.”

“Yes, I was in the team.”

Barnes was an enthusiastic cricketer. He studied his Wisden, and he had an immense respect for Wrykyn cricket.

“Are you the M. Jackson, then, who had an average of fifty-one point nought three last year?”

“Yes.”

Barnes’s manner became like that of a curate talking to a bishop.

“I say,” he said, “then—er—will you play against Downing’s to-morrow?”

“Rather,” said Mike. “Thanks awfully. Have some tea?”

(To be continued.)

Note:

The name Boughton-Knight (ch. IX) was changed to Broughton-Knight in Mike (1909). Both spellings are found in compound names of British families, so it is not clear which was Wodehouse’s preference.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums