The Captain, November 1908

CHAPTER VI.

psmith explains.

OR the space of about

twenty-five minutes Psmith sat in silence, concentrated on his ledger, the

picture of the model bank-clerk. Then he flung down his pen, slid from his

stool with a satisfied sigh, and dusted his waistcoat. “A commercial crisis,”

he said, “has passed. The job of work which Comrade Rossiter indicated for me

has been completed with masterly skill. The period of anxiety is over. The bank

ceases to totter. Are you busy, Comrade Jackson, or shall we chat awhile?”

OR the space of about

twenty-five minutes Psmith sat in silence, concentrated on his ledger, the

picture of the model bank-clerk. Then he flung down his pen, slid from his

stool with a satisfied sigh, and dusted his waistcoat. “A commercial crisis,”

he said, “has passed. The job of work which Comrade Rossiter indicated for me

has been completed with masterly skill. The period of anxiety is over. The bank

ceases to totter. Are you busy, Comrade Jackson, or shall we chat awhile?”

Mike was not busy. He had worked off the last batch of letters, and there was nothing to do but to wait for the next, or—happy thought—to take the present batch down to the post, and so get out into the sunshine and fresh air for a short time. “I rather think I’ll nip down to the post-office,” said he, “You couldn’t come too, I suppose?”

“On the contrary,” said Psmith, “I could, and will. A stroll will just restore those tissues which the gruelling work of the last half-hour has wasted away. It is a fearful strain, this commercial toil. Let us trickle towards the post office. I will leave my hat and gloves as a guarantee of good faith. The cry will go round, ‘Psmith has gone! Some rival institution has kidnapped him!’ Then they will see my hat”—he built up a foundation of ledgers, planted a long ruler in the middle, and hung his hat on it—“my gloves,”—he stuck two pens into the desk and hung a lavender glove on each—“and they will sink back swooning with relief. The awful suspense will be over. They will say, ‘No, he has not gone permanently. Psmith will return. When the fields are white with daisies he’ll return.’ And now, Comrade Jackson, lead me to this picturesque little post-office of yours of which I have heard so much.”

Mike picked up the long basket into which he had thrown the letters after entering the addresses in his ledger, and they moved off down the aisle. No movement came from Mr. Rossiter’s lair. Its energetic occupant was hard at work. They could just see part of his hunched-up back.

“I wish Comrade Downing could see us now,” said Psmith. “He always set us down as mere idlers. Triflers. Butterflies. It would be a wholesome corrective for him to watch us perspiring like this in the cause of Commerce.”

“You haven’t told me yet what on earth you’re doing here,” said Mike. “I thought you were going to the ’Varsity. Why the dickens are you in a bank? Your pater hasn’t lost his money, has he?”

“No. There is still a tolerable supply of doubloons in the old oak chest. Mine is a painful story.”

“It always is,” said Mike.

“You are very right, Comrade Jackson. I am the victim of Fate. Ah, so you put the little chaps in there, do you?” he said, as Mike, reaching the post-office, began to bundle the letters into the box. “You seem to have grasped your duties with admirable promptitude. It is the same with me. I fancy we are both born men of Commerce. In a few years we shall be pinching Comrade Bickersdyke’s job. And talking of Comrade B. brings me back to my painful story. But I shall never have time to tell it to you during our walk back. Let us drift aside into this tea-shop. We can order a buckwheat cake or a butter-nut, or something equally succulent, and carefully refraining from consuming those dainties, I will tell you all.”

“Right O!” said Mike.

“When last I saw you,” resumed Psmith, hanging Mike’s basket on the hat-stand and ordering two portions of porridge, “you may remember that a serious crisis in my affairs had arrived. My father, inflamed with the idea of Commerce, had invited Comrade Bickersdyke——”

“When did you know he was a manager here?” asked Mike.

“At an early date. I have my spies everywhere. However, my pater invited Comrade Bickersdyke to our house for the week-end. Things turned out rather unfortunately. Comrade B. resented my purely altruistic efforts to improve him mentally and morally. Indeed, on one occasion he went so far as to call me an impudent young cub, and to add that he wished he had me under him in his bank, where, he asserted, he would knock some of the nonsense out of me. All very painful. I tell you, Comrade Jackson, for the moment it reduced my delicately vibrating ganglions to a mere frazzle. Recovering myself, I made a few blithe remarks, and we then parted. I cannot say that we parted friends, but at any rate I bore him no ill-will. I was still determined to make him a credit to me. My feelings towards him were those of some kindly father to his prodigal son. But he, if I may say so, was fairly on the hop. And when my pater, after dinner the same night, played into his hands by mentioning that he thought I ought to plunge into a career of commerce, Comrade B. was, I gather, all over him. Offered to make a vacancy for me in the bank, and to take me on at once. My pater, feeling that this was the real hustle which he admired so much, had me in, stated his case, and said, in effect, ‘How do we go?’ I intimated that Comrade Bickersdyke was my greatest chum on earth. So the thing was fixed up and here I am. But you are not getting on with your porridge, Comrade Jackson. Perhaps you don’t care for porridge? Would you like a finnan haddock instead? Or a piece of shortbread? You have only to say the word.”

“It seems to me,” said Mike gloomily, “that we are in for a pretty rotten time of it in this bally bank. If Bickersdyke’s got his knife into us, he can make it jolly warm for us. He’s got his knife into me all right about that walking-across-the-screen business.”

“True,” said Psmith, “to a certain extent. It is an undoubted fact that Comrade Bickersdyke will have a jolly good try at making life a nuisance to us; but, on the other hand, I propose, so far as in me lies, to make things moderately unrestful for him, here and there.”

“But you can’t,” objected Mike. “What I mean to say is, it isn’t like a school. If you wanted to score off a master at school, you could always rag and so on. But here you can’t. How can you rag a man who’s sitting all day in a room of his own while you’re sweating away at a desk at the other end of the building?”

“You put the case with admirable clearness, Comrade Jackson,” said Psmith approvingly. “At the hard-headed, common-sense business you sneak the biscuit every time with ridiculous case. But you do not know all. I do not propose to do a thing in the bank except work. I shall be a model as far as work goes. I shall be flawless. I shall bound to do Comrade Rossiter’s bidding like a highly trained performing dog. It is outside the bank, when I have staggered away dazed with toil, that I shall resume my attention to the education of Comrade Bickersdyke.”

“But, dash it all, how can you? You won’t see him. He’ll go off home, or to his club, or——”

Psmith tapped him earnestly on the chest.

“There, Comrade Jackson,” he said, “you have hit the bull’s-eye, rung the bell, and gathered in the cigar or cocoanut according to choice. He will go off to his club. And I shall do precisely the same.”

“How do you mean?”

“It is this way. My father, as you may have noticed during your stay at our stately home of England, is a man of a warm, impulsive character. He does not always do things as other people would do them. He has his own methods. Thus, he has sent me into the City to do the hard-working, bank-clerk act, but at the same time he is allowing me just as large an allowance as he would have given me if I had gone to the ’Varsity. Moreover, while I was still at Eton he put my name up for his clubs, the Senior Conservative among others. My pater belongs to four clubs altogether, and in course of time, when my name comes up for election, I shall do the same. Meanwhile, I belong to one, the Senior Conservative. It is a bigger club than the others, and your name comes up for election sooner. About the middle of last month a great yell of joy made the West End of London shake like a jelly. The three thousand members of the Senior Conservative had just learned that I had been elected.”

Psmith paused, and ate some porridge.

“I wonder why they call this porridge,” he observed with mild interest. “It would be far more manly and straightforward of them to give it its real name. To resume. I have gleaned, from casual chit-chat with my father, that Comrade Bickersdyke also infests the Senior Conservative. You might think that that would make me, seeing how particular I am about whom I mix with, avoid the club. Error. I shall go there every day. If Comrade Bickersdyke wishes to emend any little traits in my character of which he may disapprove, he shall never say that I did not give him the opportunity. I shall mix freely with Comrade Bickersdyke at the Senior Conservative Club. I shall be his constant companion. I shall, in short, haunt the man. By these strenuous means I shall, as it were, get a bit of my own back. And now,” said Psmith, rising, “it might be as well, perhaps, to return to the bank and resume our commercial duties. I don’t know how long you are supposed to be allowed for your little trips to and from the post-office, but, seeing that the distance is about thirty yards, I should say at a venture not more than half an hour. Which is exactly the space of time which has flitted by since we started out on this important expedition. Your devotion to porridge, Comrade Jackson, has led to our spending about twenty-five minutes in this hostelry.”

“Great Scott,” said Mike, “there’ll be a row.”

“Some slight temporary breeze, perhaps,” said Psmith. “Annoying to men of culture and refinement, but not lasting. My only fear is lest we may have worried Comrade Rossiter at all. I regard Comrade Rossiter as an elder brother, and would not cause him a moment’s heart-burning for worlds. However, we shall soon know,” he added, as they passed into the bank and walked up the aisle, “for there is Comrade Rossiter waiting to receive us in person.”

The little head of the Postage Department was moving restlessly about in the neighbourhood of Psmith’s and Mike’s desk.

“Am I mistaken,” said Psmith to Mike, “or is there the merest suspicion of a worried look on our chief’s face? It seems to me that there is the slightest soupçon of shadow about that broad, calm brow.”

CHAPTER VII.

going into winter quarters.

HERE was.

HERE was.

Mr. Rossiter had discovered Psmith’s and Mike’s absence about five minutes after they had left the building. Ever since then, he had been popping out of his lair at intervals of three minutes, to see whether they had returned. Constant disappointment in this respect had rendered him decidedly jumpy. When Psmith and Mike reached the desk, he was a kind of human soda-water bottle. He fizzed over with questions, reproofs and warnings.

“What does it mean? What does it mean?” he cried. “Where have you been? Where have you been?”

“Poetry,” said Psmith approvingly.

“You have been absent from your places for over half an hour. Why? Why? Why? Where have you been? Where have you been? I cannot have this. It is preposterous. Where have you been? Suppose Mr. Bickersdyke had happened to come round here. I should not have known what to say to him.”

“Never an easy man to chat with, Comrade Bickersdyke,” agreed Psmith.

“You must thoroughly understand that you are expected to remain in your places during business hours.”

“Of course,” said Psmith, “that makes it a little hard for Comrade Jackson to post letters, does it not?”

“Have you been posting letters?”

“We have,” said Psmith. “You have wronged us. Seeing our absent places you jumped rashly to the conclusion that we were merely gadding about in pursuit of pleasure. Error. All the while, we were furthering the bank’s best interests by posting letters.”

“You had no business to leave your place. Jackson is on the posting desk.”

“You are very right,” said Psmith, “and it shall not occur again. It was only because it was the first day. Comrade Jackson is not used to the stir and bustle of the City. His nerve failed him. He shrank from going to the post-office alone. So I volunteered to accompany him. And,” concluded Psmith, impressively, “we won safely through. Every letter has been posted.”

“That need not have taken you half an hour.”

“True. And the actual work did not. It was carried through swiftly and surely. But the nerve-strain had left us shaken. Before resuming our more ordinary duties we had to refresh. A brief breathing-space, a little coffee and porridge, and here we are, fit for work once more.”

“If it occurs again, I shall report the matter to Mr. Bickersdyke.”

“And rightly so,” said Psmith, earnestly. “Quite rightly so. Discipline, discipline. That is the cry. There must be no shirking of painful duties. Sentiment must play no part in business. Rossiter, the man, may sympathise, but Rossiter, the Departmental head, must be adamant.”

Mr. Rossiter pondered over this for a moment, then went off on a side-issue.

“What is the meaning of this foolery?” he asked, pointing to Psmith’s gloves and hat. “Suppose Mr. Bickersdyke had come round, and seen them, what should I have said?”

“You would have given him a message of cheer. You would have said, ‘All is well. Psmith has not left us. He will come back.’ And Comrade Bickersdyke, relieved, would have——”

“You do not seem very busy, Mr. Smith.”

Both Psmith and Mr. Rossiter were startled.

Mr. Rossiter jumped as if somebody had run a gimlet into him, and even Psmith started slightly. They had not heard Mr. Bickersdyke approaching. Mike, who had been stolidly entering addresses in his ledger during the latter part of the conversation, was also taken by surprise.

Psmith was the first to recover. Mr. Rossiter was still too confused for speech, but Psmith took the situation in hand.

“Apparently no,” he said, swiftly removing his hat from the ruler. “In reality, yes. Mr. Rossiter and I were just scheming out a line of work for me as you came up. If you had arrived a moment later, you would have found me toiling.”

“H’m. I hope I should. We do not encourage idling in this bank.”

“Assuredly not,” said Psmith warmly. “Most assuredly not. I would not have it otherwise. I am a worker. A bee, not a drone. A Lusitania, not a limpet. Perhaps I have not yet that grip on my duties which I shall soon acquire; but it is coming. It is coming. I see daylight.”

“H’m. I have only your word for it.” He turned to Mr. Rossiter, who had now recovered himself, and was as nearly calm as it was in his nature to be. “Do you find Mr. Smith’s work satisfactory, Mr. Rossiter?”

Psmith waited resignedly for an outburst of complaint respecting the small matter that had been under discussion between the head of the department and himself; but to his surprise it did not come.

“Oh—ah—quite, quite, Mr. Bickersdyke. I think he will very soon pick things up.”

Mr. Bickersdyke turned away. He was a conscientious bank-manager, and one can only suppose that Mr. Rossiter’s tribute to the earnestness of one of his employés was gratifying to him. But for that, one would have said that he was disappointed.

“Oh, Mr. Bickersdyke,” said Psmith.

The manager stopped.

“Father sent his kind regards to you,” said Psmith benevolently.

Mr. Bickersdyke walked off without comment.

“An uncommonly cheery, companionable feller,” murmured Psmith, as he turned to his work.

The first day anywhere, if one spends it in a sedentary fashion, always seemed unending; and Mike felt as if he had been sitting at his desk for weeks when the hour for departure came. A bank’s day ends gradually, reluctantly, as it were. At about five there is a sort of stir, not unlike the stir in a theatre when the curtain is on the point of falling. Ledgers are closed with a bang. Men stand about and talk for a moment or two before going to the basement for their hats and coats. Then, at irregular intervals, forms pass down the central aisle and out through the swing-doors. There is an air of relaxation over the place, though some departments are still working as hard as ever under a blaze of electric light. Somebody begins to sing, and an instant chorus of protests and maledictions rises from all sides. Gradually, however, the electric lights go out. The procession down the centre aisle becomes more regular; and eventually the place is left to darkness and the night-watchman.

The postage department was one of the last to be freed from duty. This was due to the inconsiderateness of the other departments, which omitted to disgorge their letters till the last moment. Mike, as he grew familiar with the work, and began to understand it, used to prowl round the other departments during the afternoon and wrest letters from them, usually receiving with them much abuse for being a nuisance and not leaving honest workers alone. To-day, however, he had to sit on till nearly six, waiting for the final batch of correspondence.

Psmith, who had waited patiently with him, though his own work was finished, accompanied him down to the post-office and back again to the bank to return the letter basket; and they left the office together.

“By the way,” said Psmith, “what with the strenuous labours of the bank and the disturbing interviews with the powers that be, I have omitted to ask you where you are digging. Wherever it is, of course you must clear out. It is imperative, in this crisis, that we should be together. I have acquired a quite snug little flat in Clement’s Inn. There is a spare bedroom. It shall be yours.”

“My dear chap,” said Mike, “it’s all rot. I can’t sponge on you.”

“You pain me, Comrade Jackson. I was not suggesting such a thing. We are business men, hard-headed young bankers. I make you a business proposition. I offer you the post of confidential secretary and adviser to me in exchange for a comfortable home. The duties will be light. You will be required to refuse invitations to dinner from crowned heads, and to listen attentively to my views on Life. Apart from this, there is little to do. So that’s settled.”

“It isn’t,” said Mike. “I——”

“You will enter upon your duties to-night. Where are you suspended at present?”

“Dulwich. But, look here——”

“A little more, and you’ll get the sack. I tell you the thing is settled. Now, let us hail yon taximeter cab, and desire the stern-faced aristocrat on the box to drive us to Dulwich. We will then collect a few of your things in a bag, have the rest sent off by train, come back in the taxi, and go and bite a chop at the Carlton. This is a momentous day in our careers, Comrade Jackson. We must buoy ourselves up.”

Mike made no further objections. The thought of that bed-sitting room in Acacia Road and the pantomime dame rose up and killed them. After all, Psmith was not like any ordinary person. There would be no question of charity. Psmith had invited him to the flat in exactly the same spirit as he had invited him to his house for the cricket-week.

“You know,” said Psmith, after a silence, as they flitted through the streets in the taximeter, “one lives and learns. Were you so wrapped up in your work this afternoon that you did not hear my very entertaining little chat with Comrade Bickersdyke, or did it happen to come under your notice? It did? Then I wonder if you were struck by the singular conduct of Comrade Rossiter?”

“I thought it rather decent of him not to give you away to that blighter Bickersdyke.”

“Admirably put. It was precisely that that struck me. He had his opening, all ready made for him, but he refrained from depositing me in the soup. I tell you, Comrade Jackson, my rugged old heart was touched. I said to myself, ‘There must be good in Comrade Rossiter, after all. I must cultivate him.’ I shall make it my business to be kind to our Departmental head. He deserves the utmost consideration. His action shone like a good deed in a wicked world. Which it was, of course. From to-day onwards I take Comrade Rossiter under my wing. We seem to be getting into a tolerably benighted quarter. Are we anywhere near? ‘Through Darkest Dulwich in a Taximeter.’ ”

The cab arrived at Dulwich station, and Mike stood up to direct the driver. They whirred down Acacia Road. Mike stopped the cab and got out. A brief and somewhat embarrassing interview with the pantomime dame, during which Mike was separated from a week’s rent in lieu of notice, and he was in the cab again, bound for Clement’s Inn.

His feelings that night differed considerably from the frame of mind in which he had gone to bed the night before. It was partly a very excellent dinner and partly the fact that Psmith’s flat, though at present in some disorder, was obviously going to be extremely comfortable, that worked the change. But principally it was due to his having found an ally. The gnawing loneliness had gone. He did not look forward to a career of Commerce with any greater pleasure than before; but there was no doubt that with Psmith, it would be easier to get through the time after office-hours. If all went well in the bank, he might find that he had not drawn such a bad ticket after all.

CHAPTER VIII.

the friendly native.

HE first principle

of warfare,” said Psmith at breakfast next morning, doling out bacon and eggs

with the air of a mediæval monarch distributing largesse, “is to collect a

gang, to rope in allies, to secure the cooperation of some friendly native. You

may remember that at Sedleigh it was partly the sympathetic cooperation of that

record blitherer, Comrade Jellicoe, which enabled us to nip the pro-Spiller

movement in the bud. It is the same in the present crisis. What Comrade

Jellicoe was to us at Sedleigh, Comrade Rossiter must be in the City. We must

make an ally of that man. Once I know that he and I are as brothers, and that he

will look with a lenient and benevolent eye on any little shortcomings in my

work, I shall be able to devote my attention whole-heartedly to the moral

reformation of Comrade Bickersdyke, that man of blood. I look on Comrade

Bickersdyke as a bargee of the most pronounced type; and anything I can do

towards making him a decent member of Society shall be done freely and

ungrudgingly. A trifle more tea, Comrade Jackson?”

HE first principle

of warfare,” said Psmith at breakfast next morning, doling out bacon and eggs

with the air of a mediæval monarch distributing largesse, “is to collect a

gang, to rope in allies, to secure the cooperation of some friendly native. You

may remember that at Sedleigh it was partly the sympathetic cooperation of that

record blitherer, Comrade Jellicoe, which enabled us to nip the pro-Spiller

movement in the bud. It is the same in the present crisis. What Comrade

Jellicoe was to us at Sedleigh, Comrade Rossiter must be in the City. We must

make an ally of that man. Once I know that he and I are as brothers, and that he

will look with a lenient and benevolent eye on any little shortcomings in my

work, I shall be able to devote my attention whole-heartedly to the moral

reformation of Comrade Bickersdyke, that man of blood. I look on Comrade

Bickersdyke as a bargee of the most pronounced type; and anything I can do

towards making him a decent member of Society shall be done freely and

ungrudgingly. A trifle more tea, Comrade Jackson?”

“No, thanks,” said Mike. “I’ve done. By Jove, Smith, this flat of yours is all right.”

“Not bad,” assented Psmith, “not bad. Free from squalor to a great extent. I have a number of little objects of vertu coming down shortly from the old homestead. Pictures, and so on. It will be by no means un-snug when they are up. Meanwhile, I can rough it. We are old campaigners, we Psmiths. Give us a roof, a few comfortable chairs, a sofa or two, half a dozen cushions, and decent meals, and we do not repine. Reverting once more to Comrade Rossiter——”

“Yes, what about him?” said Mike. “You’ll have a pretty tough job turning him into a friendly native, I should think. How do you mean to start?”

Psmith regarded him with a benevolent eye.

“There is but one way,” he said. “Do you remember the case of Comrade Outwood, at Sedleigh? How did we corral him, and become to him practically as long-lost sons?”

“We got round him by joining the Archæological Society.”

“Precisely,” said Psmith. “Every man has his hobby. The thing is to find it out. In the case of comrade Rossiter, I should say that it would be either postage stamps, dried seaweed, or Hall Caine. I shall endeavour to find out to-day. A few casual questions, and the thing is done. Shall we be putting in an appearance at the busy hive now? If we are to continue in the running for the bonus stakes, it would be well to start soon.”

Mike’s first duty at the bank that morning was to check the stamps and petty cash. While he was engaged on this task, he heard Psmith conversing affably with Mr. Rossiter.

“Good morning,” said Psmith.

“Morning,” replied his chief, doing sleight-of-hand tricks with a bundle of letters which lay on his desk. “Get on with your work, Psmith. We have a lot before us.”

“Undoubtedly. I am all impatience. I should say that in an institution like this, dealing as it does with distant portions of the globe, a philatelist would have excellent opportunities of increasing his collection. With me, stamp-collecting has always been a positive craze. I——”

“I have no time for nonsense of that sort myself,” said Mr. Rossiter. “I should advise you, if you mean to get on, to devote more time to your work and less to stamps.”

“I will start at once. Dried seaweed, again——”

“Get on with your work, Smith.”

Psmith retired to his desk.

“This,” he said to Mike, “is undoubtedly something in the nature of a set-back. I have drawn blank. The papers bring out posters, ‘Psmith Baffled.’ I must try again. Meanwhile, to work. Work, the hobby of the philosopher and the poor man’s friend.”

The morning dragged slowly on without incident. At twelve o’clock Mike had to go out and buy stamps, which he subsequently punched in the punching-machine in the basement, a not very exhilarating job in which he was assisted by one of the bank messengers, who discoursed learnedly on roses during the séance. Roses were his hobby. Mike began to see that Psmith had reason in his assumption that the way to every man’s heart was through his hobby. Mike made a firm friend of William, the messenger, by displaying an interest and a certain knowledge of roses. At the same time the conversation had the bad effect of leading to an acute relapse in the matter of home-sickness. The rose-garden at home had been one of Mike’s favourite haunts on a summer afternoon. The contrast between it and the basement of the new Asiatic Bank, the atmosphere of which was far from being rose-like, was too much for his feelings. He emerged from the depths, with his punched stamps, filled with bitterness against Fate.

He found Psmith still baffled.

“Hall Caine,” said Psmith regretfully, “has also proved a frost. I wandered round to Comrade Rossiter’s desk just now with a rather brainy excursus on ‘The Eternal City,’ and was received with the Impatient Frown rather than the Glad Eye. He was in the middle of adding up a rather tricky column of figures, and my remarks caused him to drop a stitch. So far from winning the man over, I have gone back. There now exists between Comrade Rossiter and myself a certain coldness. Further investigations will be postponed till after lunch.”

The postage department received visitors during the morning. Members of other departments came with letters, among them Bannister. Mr. Rossiter was away in the manager’s room at the time.

“How are you getting on?” said Bannister to Mike.

“Oh, all right,” said Mike.

“Had any trouble with Rossiter yet?”

“No, not much.”

“He hasn’t run you in to Bickersdyke?”

“No.”

“Pardon my interrupting a conversation between old college chums,” said Psmith courteously, “but I happened to overhear, as I toiled at my desk, the name of Comrade Rossiter.”

Bannister looked somewhat startled. Mike introduced them.

“This is Smith,” he said. “Chap I was at school with. This is Bannister, Smith, who used to be on here till I came.”

“In this department?” asked Psmith.

“Yes.”

“Then, Comrade Bannister, you are the very man I have been looking for. Your knowledge will be invaluable to us. I have no doubt that, during your stay in this excellently managed department, you had many opportunities of observing Comrade Rossiter?”

“I should jolly well think I had,” said Bannister with a laugh. “He saw to that. He was always popping out and cursing me about something.”

“Comrade Rossiter’s manners are a little restive,” agreed Psmith. “What used you to talk to him about?”

“What used I to talk to him about?”

“Exactly. In those interviews to which you have alluded, how did you amuse, entertain Comrade Rossiter?”

“I didn’t. He used to do all the talking there was.”

Psmith straightened his tie, and clicked his tongue, disappointed.

“This is unfortunate,” he said, smoothing his hair. “You see, Comrade Bannister, it is this way. In the course of my professional duties, I find myself continually coming into contact with Comrade Rossiter.”

“I bet you do,” said Bannister.

“On these occasions I am frequently at a loss for entertaining conversation. He has no difficulty, as apparently happened in your case, in keeping up his end of the dialogue. The subject of my shortcomings provides him with ample material for speech. I, on the other hand, am dumb. I have nothing to say.”

“I should think that was a bit of a change for you, wasn’t it?”

“Perhaps, so,” said Psmith, “perhaps so. On the other hand, however restful it may be to myself, it does not enable me to secure Comrade Rossiter’s interest and win his esteem.”

“What Smith wants to know,” said Mike, “is whether Rossiter has any hobby of any kind. He thinks, if he has, he might work it to keep in with him.”

Psmith, who had been listening with an air of pleased interest, much as a father would listen to his child prattling for the benefit of a visitor, confirmed this statement.

“Comrade Jackson,” he said, “has put the matter with his usual admirable clearness. That is the thing in a nutshell. Has Comrade Rossiter any hobby that you know of? Spillikins, brass-rubbing, the Near Eastern Question, or anything like that? I have tried him with postage-stamps (which you’d think, as head of a postage department, he ought to be interested in), dried seaweed, and Hall Caine, but I have the honour to report total failure. The man seems to have no pleasures. What does he do with himself when the day’s toil is ended? That giant brain must occupy itself somehow.”

“I don’t know,” said Bannister, “unless it’s football. I saw him once watching Chelsea. I was rather surprised.”

“Football,” said Psmith thoughtfully, “football. By no means a scaly idea. I rather fancy, Comrade Bannister, that you have whanged the nail on the head. Is he strong on any particular team? I mean, have you ever heard him, in the intervals of business worries, stamping on his desk and yelling, ‘Buck up, Cottagers!’ or ‘Lay ’em out, Pensioners!’ or anything like that? One moment.” Psmith held up his hand. “I will get my Sherlock Holmes system to work. What was the other team in the modern gladiatorial contest at which you saw Comrade Rossiter?”

“Manchester United.”

“And Comrade Rossiter, I should say, was a Manchester man.”

“I believe he is.”

“Then I am prepared to bet a small sum that he is nuts on Manchester United. My dear Holmes, how—! Elementary, my dear fellow, quite elementary. But here comes the lad in person.”

Mr. Rossiter turned in from the central aisle through the counter-door, and, observing the conversational group at the postage-desk, came bounding up. Bannister moved off.

“Really, Smith,” said Mr. Rossiter, “you always seem to be talking. I have overlooked the matter once, as I did not wish to get you into trouble so soon after joining; but, really, it cannot go on. I must take notice of it.”

Psmith held up his hand.

“The fault was mine,” he said, with manly frankness. “Entirely mine. Bannister came in a purely professional spirit to deposit a letter with Comrade Jackson. I engaged him in conversation on the subject of the Football League, and I was just trying to correct his view that Newcastle United were the best team playing, when you arrived.”

“It is perfectly absurd,” said Mr. Rossiter, “that you should waste the bank’s time in this way. The bank pays you to work, not to talk about professional football.”

“Just so, just so,” murmured Psmith.

“There is too much talking in this department.”

“I fear you are right.”

“It is nonsense.”

“My own view,” said Psmith, “was that Manchester United were by far the finest team before the public.”

“Get on with your work, Smith.”

Mr. Rossiter stumped off to his desk, where he sat as one in thought.

“Smith,” he said at the end of five minutes.

Psmith slid from his stool, and made his way deferentially towards him.

“Bannister’s a fool,” snapped Mr. Rossiter.

“So I thought,” said Psmith.

“A perfect fool. He always was.”

Psmith shook his head sorrowfully, as who should say, “Exit Bannister.”

“There is no team playing to-day to touch Manchester United.”

“Precisely what I said to Comrade Bannister.”

“Of course. You know something about it.”

“The study of League football,” said Psmith, “has been my relaxation for years.”

“But we have no time to discuss it now.”

“Assuredly not, sir. Work before everything.”

“Some other time, when——”

“——We are less busy. Precisely.”

Psmith moved back to his seat.

“I fear,” he said to Mike, as he resumed work, “that as far as Comrade Rossiter’s friendship and esteem are concerned, I have to a certain extent landed Comrade Bannister in the bouillon; but it was in a good cause. I fancy we have won through. Half an hour’s thoughtful perusal of the ‘Footballers’ Who’s Who,’ just to find out some elementary facts about Manchester United, and I rather think the Friendly Native is corralled. And now once more to work. Work, the hobby of the hustler and the deadbeat’s dread.”

CHAPTER IX.

the haunting of mr. bickersdyke.

NYTHING in the nature

of a rash and hasty move was wholly foreign to Psmith’s tactics. He had the

patience which is the chief quality of the successful general. He was content

to secure his base before making any offensive movement. It was a fortnight

before he turned his attention to the education of Mr. Bickersdyke. During that

fortnight he conversed attractively, in the intervals of work, on the subject

of League football in general and Manchester United in particular. The subject

is not hard to master if one sets oneself earnestly to it; and Psmith spared no

pains. The football editions of the evening papers are not reticent about those

who play the game: and Psmith drank in every detail with the thoroughness of

the conscientious student. By the end of the fortnight he knew what was the

favourite breakfast-food of J. Turnbull; what Sandy Turnbull wore next his

skin; and who, in the opinion of Meredith, was England’s leading politician.

These facts, imparted to and discussed with Mr. Rossiter, made the progress of

the entente cordiale rapid. It was on the eighth day that Mr. Rossiter

consented to lunch with the Old Etonian. On the tenth he played the host. By

the end of the fortnight the flapping of the white wings of Peace over the

Postage Department was setting up a positive draught. Mike, who had been

introduced by Psmith as a distant relative of Moger, the goalkeeper, was

included in the great peace.

NYTHING in the nature

of a rash and hasty move was wholly foreign to Psmith’s tactics. He had the

patience which is the chief quality of the successful general. He was content

to secure his base before making any offensive movement. It was a fortnight

before he turned his attention to the education of Mr. Bickersdyke. During that

fortnight he conversed attractively, in the intervals of work, on the subject

of League football in general and Manchester United in particular. The subject

is not hard to master if one sets oneself earnestly to it; and Psmith spared no

pains. The football editions of the evening papers are not reticent about those

who play the game: and Psmith drank in every detail with the thoroughness of

the conscientious student. By the end of the fortnight he knew what was the

favourite breakfast-food of J. Turnbull; what Sandy Turnbull wore next his

skin; and who, in the opinion of Meredith, was England’s leading politician.

These facts, imparted to and discussed with Mr. Rossiter, made the progress of

the entente cordiale rapid. It was on the eighth day that Mr. Rossiter

consented to lunch with the Old Etonian. On the tenth he played the host. By

the end of the fortnight the flapping of the white wings of Peace over the

Postage Department was setting up a positive draught. Mike, who had been

introduced by Psmith as a distant relative of Moger, the goalkeeper, was

included in the great peace.

“So that now,” said Psmith, reflectively polishing his eye-glass, “I think that we may consider ourselves free to attend to Comrade Bickersdyke. Our bright little Mancunian friend would no more run us in now than if we were the brothers Turnbull. We are as inside forwards to him.”

The club to which Psmith and Mr. Bickersdyke belonged was celebrated for the steadfastness of its political views, the excellence of its cuisine, and the curiously Gorgonzolaesque marble of its main staircase. It takes all sorts to make a world. It took about four thousand of all sorts to make the Senior Conservative Club. To be absolutely accurate, there were three thousand seven hundred and eighteen members.

To Mr. Bickersdyke for the next week it seemed as if there was only one.

There was nothing crude or overdone about Psmith’s methods. The ordinary man, having conceived the idea of haunting a fellow clubman, might have seized the first opportunity of engaging him in conversation. Not so Psmith. The first time he met Mr. Bickersdyke in the club was on the stairs after dinner one night. The great man, having received practical proof of the excellence of cuisine referred to above, was coming down the main staircase at peace with all men, when he was aware of a tall young man in the “faultless evening dress” of which the female novelist is so fond, who was regarding him with a fixed stare through an eye-glass. The tall young man, having caught his eye, smiled faintly, nodded in a friendly but patronising manner, and passed on up the staircase to the library. Mr. Bickersdyke sped on in search of a waiter.

As Psmith sat in the library with a novel, the waiter entered, and approached him.

“Beg pardon, sir,” he said. “Are you a member of this club?”

Psmith fumbled in his pocket and produced his eye-glass, through which he examined the waiter, button by button.

“I am Psmith,” he said simply.

“A member, sir?”

“The member,” said Psmith. “Surely you participated in the general rejoicings which ensued when it was announced that I had been elected? But perhaps you were too busy working to pay any attention. If so, I respect you. I also am a worker. A toiler, not a flat-fish. A sizzler, not a squab. Yes, I am a member. Will you tell Mr. Bickersdyke that I am sorry, but I have been elected, and have paid my entrance fee and subscription.”

“Thank you, sir.”

The waiter went downstairs and found Mr. Bickersdyke in the lower smoking-room.

“The gentleman says he is, sir.”

“H’m,” said the bank-manager. “Coffee and Benedictine, and a cigar.”

“Yes, sir.”

On the following day Mr. Bickersdyke met Psmith in the club three times, and on the day after that seven. Each time the latter’s smile was friendly, but patronising. Mr. Bickersdyke began to grow restless.

On the fourth day Psmith made his first remark. The manager was reading the evening paper in a corner, when Psmith sinking gracefully into a chair beside him, caused him to look up.

“The rain keeps off,” said Psmith.

Mr. Bickersdyke looked as if he wished his employee would imitate the rain, but he made no reply.

Psmith called a waiter.

“Would you mind bringing me a small cup of coffee?” he said. “And for you,” he added to Mr. Bickersdyke.

“Nothing,” growled the manager.

“And nothing for Mr. Bickersdyke.”

The waiter retired. Mr. Bickersdyke became absorbed in his paper.

“I see from my morning paper,” said Psmith, affably, “that you are to address a meeting at the Kenningford Town Hall next week. I shall come and hear you. Our politics differ in some respects, I fear—I incline to the Socialist view—but nevertheless I shall listen to your remarks with great interest, great interest.”

The paper rustled, but no reply came from behind it.

“I heard from father this morning,” resumed Psmith.

Mr. Bickersdyke lowered his paper and glared at him.

“I don’t wish to hear about your father,” he snapped.

An expression of surprise and pain came over Psmith’s face.

“What!” he cried. “You don’t mean to say that there is any coolness between my father and you? I am more grieved than I can say. Knowing, as I do, what a genuine respect my father has for your great talents, I can only think that there must have been some misunderstanding. Perhaps if you would allow me to act as a mediator——”

Mr. Bickersdyke put down his paper and walked out of the room.

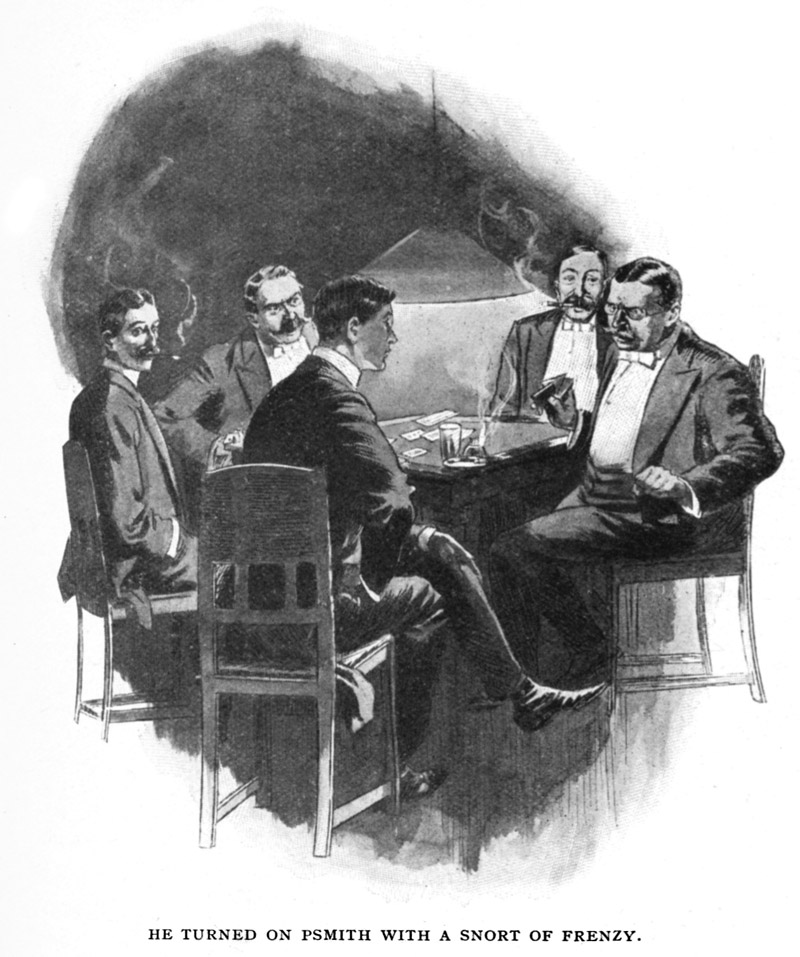

Psmith found him a quarter of an hour later in the card-room. He sat down beside his table, and began to observe the play with silent interest. Mr. Bickersdyke, never a great performer at the best of times, was so unsettled by the scrutiny that in the deciding game of the rubber he revoked, thereby presenting his opponents with the rubber by a very handsome majority of points. Psmith clicked his tongue sympathetically.

Dignified reticence is not a leading characteristic of the bridge-player’s manner at the Senior Conservative Club on occasions like this. Mr. Bickersdyke’s partner did not bear his calamity with manly resignation. He gave tongue on the instant. “What on earth’s” and “Why on earth’s” flowed from his mouth like molten lava. Mr. Bickersdyke sat and fermented in silence. Psmith clicked his tongue sympathetically throughout.

Mr. Bickersdyke lost that control over himself which every member of a club should possess. He turned on Psmith with a snort of frenzy.

“How can I keep my attention fixed on the game when you sit staring at me like a—like a——”

“I am sorry,” said Psmith gravely, “if my stare falls short in any way of your ideal of what a stare should be; but I appeal to these gentlemen. Could I have watched the game more quietly?”

“Of course not,” said the bereaved partner warmly. “Nobody could have any earthly objection to your behaviour. It was absolute carelessness. I should have thought that one might have expected one’s partner at a club like this to exercise elementary——”

But Mr. Bickersdyke had gone. He had melted silently away like the driven snow.

Psmith took his place at the table.

“A somewhat nervous, excitable man, Mr. Bickersdyke, I should say,” he observed.

“A somewhat dashed, blanked idiot,” emended the bank-manager’s late partner. “Thank goodness he lost as much as I did. That’s some slight consolation.”

Psmith arrived at the flat to find Mike still out. Mike had repaired to the Gaiety earlier in the evening to refresh his mind after the labours of the day. When he returned, Psmith was sitting in an arm-chair with his feet on the mantelpiece, musing placidly on Life.

“Well?” said Mike.

“Well? And how was the Gaiety? Good show?”

“Jolly good. What about Bickersdyke?”

Psmith looked sad.

“I cannot make Comrade Bickersdyke out,” he said. “You would think that a man would be glad to see the son of a personal friend. On the contrary, I may be wronging Comrade B., but I should almost be inclined to say that my presence in the Senior Conservative Club to-night irritated him. There was no bonhomie in his manner. He seemed to me to be giving a spirited imitation of a man about to foam at the mouth. I did my best to entertain him. I chatted. His only reply was to leave the room. I followed him to the card-room, and watched his very remarkable and brainy tactics at bridge, and he accused me of causing him to revoke. A very curious personality, that of Comrade Bickersdyke. But let us dismiss him from our minds. Rumours have reached me,” said Psmith, “that a very decent little supper may be obtained at a quaint, old-world eating-house called the Savoy. Will you accompany me thither on a tissue-restoring expedition? It would be rash not to probe these rumours to their foundation, and ascertain their exact truth.”

CHAPTER X.

mr. bickersdyke addresses his constituents.

T was noted by the

observant at the bank next morning that Mr. Bickersdyke had something on his

mind. William, the messenger, knew it, when he found his respectful salute

ignored. Little Briggs, the accountant, knew it when his obsequious but

cheerful “Good morning” was acknowledged only by a “Morn’ ” which was almost an

oath. Mr. Bickersdyke passed up the aisle and into his room like an east wind.

He sat down at his table and pressed the bell. Harold, William’s brother and

co-messenger, entered with the air of one ready to duck if any missile should

be thrown at him. The reports of the manager’s frame of mind had been

circulated in the office, and Harold felt somewhat apprehensive. It was on an

occasion very similar to this that George Barstead, formerly in the employ of

the New Asiatic Bank in the capacity of messenger, had been rash enough to

laugh at what he had taken for a joke of Mr. Bickersdyke’s, and had been

instantly presented with the sack for gross impertinence.

T was noted by the

observant at the bank next morning that Mr. Bickersdyke had something on his

mind. William, the messenger, knew it, when he found his respectful salute

ignored. Little Briggs, the accountant, knew it when his obsequious but

cheerful “Good morning” was acknowledged only by a “Morn’ ” which was almost an

oath. Mr. Bickersdyke passed up the aisle and into his room like an east wind.

He sat down at his table and pressed the bell. Harold, William’s brother and

co-messenger, entered with the air of one ready to duck if any missile should

be thrown at him. The reports of the manager’s frame of mind had been

circulated in the office, and Harold felt somewhat apprehensive. It was on an

occasion very similar to this that George Barstead, formerly in the employ of

the New Asiatic Bank in the capacity of messenger, had been rash enough to

laugh at what he had taken for a joke of Mr. Bickersdyke’s, and had been

instantly presented with the sack for gross impertinence.

“Ask Mr. Smith——” began the manager. Then he paused. “No, never mind,” he added.

Harold remained in the doorway, puzzled.

“Don’t stand there gaping at me, man,” cried Mr. Bickersdyke. “Go away.”

Harold retired and informed his brother, William, that in his, Harold’s, opinion, Mr. Bickersdyke was off his chump.

“Off his onion,” said William, soaring a trifle higher in poetic imagery.

“Barmy,” was the terse verdict of Samuel Jakes, the third messenger. “Always said so.” And with that the New Asiatic Bank staff of messengers dismissed Mr. Bickersdyke and proceeded to concentrate themselves on their duties; which consisted principally of hanging about and discussing the prophecies of that modern seer, Captain Coe.

What had made Mr. Bickersdyke change his mind so abruptly was the sudden realization of the fact that he had no case against Psmith. In his capacity of manager of the bank he could not take official notice of Psmith’s behaviour outside office hours, especially as Psmith had done nothing but stare at him. It would be impossible to make anybody understand the true inwardness of Psmith’s stare. Theoretically, Mr. Bickersdyke had the power to dismiss any subordinate of his whom he did not consider satisfactory, but it was a power that had to be exercised with discretion. The manager was accountable for his actions to the Board of Directors. If he dismissed Psmith, Psmith would certainly bring an action against the bank for wrongful dismissal, and on the evidence he would infallibly win it. Mr. Bickersdyke did not welcome the prospect of having to explain to the Directors that he had let the shareholders of the bank in for a fine of whatever a discriminating jury cared to decide upon, simply because he had been stared at while playing bridge. His only hope was to catch Psmith doing his work badly.

He touched the bell again, and sent for Mr. Rossiter.

The messenger found the head of the Postage Department in conversation with Psmith. Manchester United had been beaten by one goal to nil on the previous afternoon, and Psmith was informing Mr. Rossiter that the referee was a robber, who had evidently been financially interested in the result of the game. The way he himself looked at it, said Psmith, was that the thing had been a moral victory for the United. Mr. Rossiter said yes, he thought so too. And it was at this moment that Mr. Bickersdyke sent for him, to ask whether Psmith’s work was satisfactory.

The head of the Postage Department gave his opinion without hesitation. Psmith’s work was about the hottest proposition he had ever struck. Psmith’s work—well, it stood alone. You couldn’t compare it with anything. There are no degrees in perfection. Psmith’s work was perfect, and there was an end to it.

He put it differently, but that was the gist of what he said.

Mr. Bickersdyke observed he was glad to hear it, and smashed a nib by stabbing the desk with it.

It was on the evening following this that the bank-manager was due to address a meeting at the Kenningford Town Hall.

He was looking forward to the event with mixed feelings. He had stood for Parliament once before, several years back, in the North. He had been defeated by a couple of thousand votes, and he hoped that the episode had been forgotten. Not merely because his defeat had been heavy. There was another reason. On that occasion he had stood as a Liberal. He was standing for Kenningford as a Unionist. Of course, a man is at perfect liberty to change his views, if he wishes to do so, but the process is apt to give his opponents a chance of catching him (to use the inspired language of the music-halls) on the bend. Mr. Bickersdyke was rather afraid that the light-hearted electors of Kenningford might avail themselves of this chance.

Kenningford, S.E., is undoubtedly by way of being a tough sort of place. Its inhabitants incline to a robust type of humour, which finds a verbal vent in catch-phrases and expends itself physically in smashing shop-windows and kicking policemen. He feared that the meeting at the Town Hall might possibly be a trifle rowdy.

All political meetings are very much alike. Somebody gets up and introduces the speaker of the evening, and then the speaker of the evening says at great length what he thinks of the scandalous manner in which the Government is behaving or the iniquitous goings-on of the Opposition. From time to time confederates in the audience rise and ask carefully rehearsed questions, and are answered fully and satisfactorily by the orator. When a genuine heckler interrupts, the orator either ignores him, or says haughtily that he can find him arguments but cannot find him brains. Or, occasionally, when the question is an easy one, he answers it. A quietly conducted political meeting is one of England’s most delightful indoor games. When the meeting is rowdy, the audience has more fun, but the speaker a good deal less.

Mr. Bickersdyke’s introducer was an elderly Scotch peer, an excellent man for the purpose in every respect, except that he possessed a very strong accent.

The audience welcomed that accent uproariously. The electors of Kenningford who really had any definite opinions on politics were fairly equally divided. There were about as many earnest Liberals as there were earnest Unionists. But besides these there was a strong contingent who did not care which side won. These looked on elections as Heaven-sent opportunities for making a great deal of noise. They attended meetings in order to extract amusement from them; and they voted, if they voted at all, quite irresponsibly. A funny story at the expense of one candidate told on the morning of the polling, was quite likely to send these brave fellows off in dozens filling in their papers for the victim’s opponent.

There was a solid block of these gay spirits at the back of the hall. They received the Scotch peer with huge delight. He reminded them of Harry Lauder and they said so. They addressed him affectionately as “ ’Arry,” throughout his speech, which was rather long. They implored him to be a pal and sing “The Saftest of the Family.” Or, failing that, “I love a lassie.” Finding they could not induce him to do this, they did it themselves. They sang it several times. When the peer, having finished his remarks on the subject of Mr. Bickersdyke, at length sat down, they cheered for seven minutes, and demanded an encore.

The meeting was in excellent spirits when Mr. Bickersdyke rose to address it.

The effort of doing justice to the last speaker had left the free and independent electors at the back of the hall slightly limp. The bank-manager’s opening remarks were received without any demonstration.

Mr. Bickersdyke spoke well. He had a penetrating, if harsh, voice, and he said what he had to say forcibly. Little by little the audience came under his spell. When, at the end of a well-turned sentence, he paused and took a sip of water, there was a round of applause, in which many of the admirers of Mr. Harry Lauder joined.

He resumed his speech. The audience listened intently. Mr. Bickersdyke, having said some nasty things about Free Trade and the Alien Immigrant, turned to the Needs of the Navy and the necessity of increasing the fleet at all costs.

“This is no time for

half-measures,” he said. “We must do our utmost. We must burn our boats——”

“This is no time for

half-measures,” he said. “We must do our utmost. We must burn our boats——”

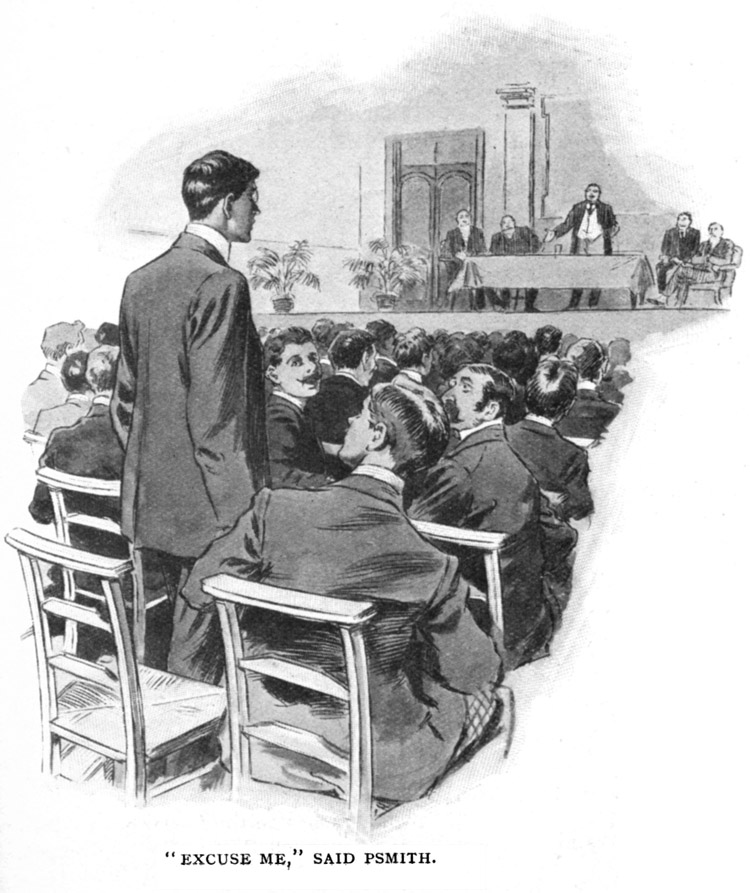

“Excuse me,” said a gentle voice.

Mr. Bickersdyke broke off. In the centre of the hall a tall figure had risen. Mr. Bickersdyke found himself looking at a gleaming eye-glass which the speaker had just polished and inserted in his eye.

The ordinary heckler Mr. Bickersdyke would have taken in his stride. He had got his audience, and simply by continuing and ignoring the interruption, he could have won through in safety. But the sudden appearance of Psmith unnerved him. He remained silent.

“How,” asked Psmith, “do you propose to strengthen the Navy by burning boats?”

The inanity of the question enraged even the pleasure-seekers at the back.

“Order! Order!” cried the earnest contingent.

“Sit down, fice!” roared the pleasure-seekers.

Psmith sat down with a patient smile.

Mr. Bickersdyke resumed his speech. But the fire had gone out of it. He had lost his audience. A moment before, he had grasped them and played on their minds (or what passed for minds down Kenningford way) as on a stringed instrument. Now he had lost his hold.

He spoke on rapidly, but he could not get into his stride. The trivial interruption had broken the spell. His words lacked grip. The dead silence in which the first part of his speech had been received, that silence which is a greater tribute to the speaker than any applause, had given place to a restless medley of little noises; here a cough; there a scraping of a boot along the floor, as its wearer moved uneasily in his seat; in another place a whispered conversation. The audience was bored.

Mr. Bickersdyke left the Navy, and went on to more general topics. But he was not interesting. He quoted figures, saw a moment later that he had not quoted them accurately, and instead of carrying on boldly, went back and corrected himself.

“Gow up top!” said a voice at the back of the hall, and there was a general laugh.

Mr. Bickersdyke galloped unsteadily on. He condemned the Government. He said they had betrayed their trust.

And then he told an anecdote.

“The Government, gentlemen,” he said, “achieves nothing worth achieving, and every individual member of the Government takes all the credit for what is done to himself. Their methods remind me, gentlemen, of an amusing experience I had while fishing one summer in the Lake District.”

In a volume entitled “Three Men in a Boat” there is a story of how the author and a friend go into a riverside inn and see a very large trout in a glass case. They make inquiries about it. Five men assure them, one by one, that the trout was caught by themselves. In the end the trout turns out to be made of plaster of Paris.

Mr. Bickersdyke told that story as an experience of his own while fishing one summer in the Lake District.

It went well. The meeting was amused. Mr. Bickersdyke went on to draw a trenchant comparison between the lack of genuine merit in the trout and the lack of genuine merit in the achievements of His Majesty’s Government.

There was applause.

When it had ceased, Psmith rose to his feet again.

“Excuse me,” he said.

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums