The Captain, November 1905

CHAPTER V.

the white feather.

T was not until he had reached his study that Sheen thoroughly realised

what he had done. All the way home he had been defending himself eloquently

against an imaginary accuser; and he had built up a very sound, thoughtful, and

logical series of arguments to show that he was not only not to blame for what

he had done, but had acted in highly statesmanlike and praiseworthy manner.

After all, he was in the sixth. Not a prefect, it was true, but, still,

practically a prefect. The headmaster disliked unpleasantness between school

and town, much more so between the sixth form of the school and the town.

Therefore, he had done his duty in refusing to be drawn into a fight with

Albert and friends. Besides, why should he be expected to join in whenever he

saw a couple of fellows fighting? It wasn’t reasonable. It was no

business of his. Why, it was absurd. He had no quarrel with those fellows. It

wasn’t cowardice. It was simply that he had kept his head better than

Drummond, and seen further into the matter. Besides. . . .

T was not until he had reached his study that Sheen thoroughly realised

what he had done. All the way home he had been defending himself eloquently

against an imaginary accuser; and he had built up a very sound, thoughtful, and

logical series of arguments to show that he was not only not to blame for what

he had done, but had acted in highly statesmanlike and praiseworthy manner.

After all, he was in the sixth. Not a prefect, it was true, but, still,

practically a prefect. The headmaster disliked unpleasantness between school

and town, much more so between the sixth form of the school and the town.

Therefore, he had done his duty in refusing to be drawn into a fight with

Albert and friends. Besides, why should he be expected to join in whenever he

saw a couple of fellows fighting? It wasn’t reasonable. It was no

business of his. Why, it was absurd. He had no quarrel with those fellows. It

wasn’t cowardice. It was simply that he had kept his head better than

Drummond, and seen further into the matter. Besides. . . .

But when he sat down in his chair, this mood changed. There is a vast difference between the view one takes of things when one is walking briskly, and that which comes when one thinks the thing over coldly. As he sat there, the wall of defence which he had built up slipped away brick by brick, and there was the fact staring at him, without covering or disguise.

It was no good arguing against himself. No amount of argument could wipe away the truth. He had been afraid, and had shown it. And he had shown it when, in a sense, he was representing the school, when Wrykyn looked to him to help it keep its end up against the town.

The more he reflected, the more he saw how far-reaching were the consequences of that failure in the hour of need. He had disgraced himself. He had disgraced Seymour’s. He had disgraced the school. He was an outcast.

This mood, the natural reaction from his first glow of almost jaunty self-righteousness, lasted till the lock-up bell rang, when it was succeeded by another. This time he took a more reasonable view of the affair. It occurred to him that there was a chance that his defection had passed unnoticed. Nothing could make his case seem better in his own eyes, but it might be that the thing would end there. The house might not have lost credit.

An overwhelming curiosity seized him to find out how it had all ended. The ten minutes of grace which followed the ringing of the lock-up bell had passed. Drummond and the rest must be back by now.

He went down the passage to Drummond’s study. Somebody was inside. He could hear him.

He knocked at the door.

Drummond was sitting at the table reading. He looked up, and there was a silence. Sheen’s mouth felt dry. He could not think how to begin. He noticed that Drummond’s face was unmarked. Looking down, he saw that one of the knuckles of the hand that held the book was swollen and cut.

“Drummond, I——”

Drummond lowered the book.

“Get out,” he said. He spoke without heat, calmly, as if he were making some conventional remark by way of starting a conversation.

“I only came to ask——”

“Get out,” said Drummond again.

There was another pause. Drummond raised his book and went on reading.

Sheen left the room.

Outside he ran into Linton. Unlike Drummond, Linton bore marks of the encounter. As in the case of the hero of Calverley’s poem, one of his speaking eyes was sable. The swelling of his lip was increased. There was a deep red bruise on his forehead. In spite of these injuries, however, he was cheerful. He was whistling when Sheen collided with him.

“Sorry,” said Linton, and went on into the study.

“Well,” he said, “how are you feeling, Drummond? Lucky beggar, you haven’t got a mark. I wish I could duck like you. Well, we have fought the good fight. Exit Albert—sweep him up. You gave him enough to last him for the rest of the term. I couldn’t tackle the brute. He’s as strong as a horse. My word, it was lucky you happened to come up. Albert was making hay of us. Still, all’s well that ends well. We have smitten the Philistines this day. By the way——”

“What’s up now?”

“Who was that chap with you when you came up?”

“Which chap?”

“I thought I saw some one.”

“You shouldn’t eat so much tea. You saw double.”

“There wasn’t anybody?”

“No,” said Drummond.

“Not Sheen?”

“No,” said Drummond, irritably. “How many more times do you want me to say it?”

“All right,” said Linton, “I only asked. I met him outside.”

“Who?”

“Sheen.”

“Oh?”

“You might be sociable.”

“I know I might. But I want to read.”

“Lucky man. Wish I could. I can hardly see. Well, good-bye, then. I’m off.”

“Good,” grunted Drummond. “You know your way out, don’t you?”

Linton went back to his own study.

“It’s all very well,” he said to himself, “for Drummond to deny it, but I’ll swear I saw Sheen with him. So did Dunstable. I’ll cut out and ask him about it after prep. If he really was there, and cut off, something ought to be done about it. The chap ought to be kicked. He’s a disgrace to the house.”

Dunstable, questioned after preparation, refused to commit himself.

“I thought I saw somebody with Drummond,” he said, “and I had a sort of idea it was Sheen. Still, I was pretty busy at the time, and wasn’t paying much attention to anything, except that long, thin bargee with the bowler. I wish those men would hit straight. It’s beastly difficult to guard a round-arm swing. My right ear feels like a cauliflower. Does it look rum?”

“Beastly. But what about this? You can’t swear to Sheen then?”

“No. Better give him the benefit of the doubt. What does Drummond say? You ought to ask him.”

“I have. He says he was alone.”

“Well, that settles it. What an ass you are. If Drummond doesn’t know, who does?”

“I believe he’s simply hushing it up.”

“Well, let us hush it up, too. It’s no good bothering about it. We licked them all right.”

“But it’s such a beastly thing for the house.”

“Then why the dickens do you want it to get about? Surely the best thing you can do is to dry up and say nothing about it.”

“But something ought to be done.”

“What’s the good of troubling about a man like Sheen? He never was any good, and this doesn’t make him very much worse. Besides, he’ll probably be sick enough on his own account. I know I should, if I’d done it. And, anyway, we don’t know that he did do it.”

“I’m certain he did. I could swear it was him.”

“Anyhow, for goodness’ sake let the thing drop.”

“All right. But I shall cut him.”

“Well, that would be punishment enough for anybody, whatever he’d done. Fancy existence without your bright conversation. It doesn’t bear thinking of. You do look a freak with that eye and that lump on your forehead. You ought to wear a mask.”

“That ear of yours,” said Linton with satisfaction, “will be about three times its ordinary size to-morrow. And it always was too large. Good-night.”

On his way back to Seymour’s, Mason, of Appleby’s, who was standing at his house gate imbibing fresh air preparatory to going to bed, accosted him.

“I say, Linton,” he said, “—hullo, you look a wreck, don’t you!—I say, what’s all this about your house?”

“What about my house?”

“Funking, and all that. Sheen, you know. Stanning has just been telling me.”

“Then he saw him, too!” exclaimed Linton, involuntarily.

“Oh, it’s true, then? Did he really cut off like that? Stanning said he did, but I wouldn’t believe him at first. You aren’t going? Good-night.”

So the thing was out. Linton had not counted on Stanning having seen what he and Dunstable had seen. It was impossible to hush it up now. The scutcheon of Seymour’s was definitely blotted. The name of the house was being held up to scorn in Appleby’s. Probably everywhere else as well. It was a nuisance, thought Linton, but it could not be helped. After all, it was a judgment on the house for harbouring such a specimen as Sheen.

In Seymour’s there was tumult and an impromptu indignation meeting. Stanning had gone to work scientifically. From the moment that, ducking under the guard of a sturdy town youth, he had caught sight of Sheen retreating from the fray, he had grasped the fact that here, ready-made, was his chance of working off his grudge against him. All he had to do was to spread the news abroad, and the school would do the rest. On his return from the town he had mentioned the facts of the case to one or two of the more garrulous members of his house, and they had passed it on to everybody they met during the interval in the middle of preparation. By the end of preparation half the school knew what had happened.

Seymour’s was furious. The senior day-room to a man condemned Sheen. The junior day-room was crimson in the face and incoherent. The demeanour of a junior in moments of excitement generally lacks that repose which marks the philosopher.

“He ought to be kicked,” shrilled Renford.

“We shall get rotted by those kids in Dexter’s,” moaned Harvey.

“Disgracing the house!” thundered Watson.

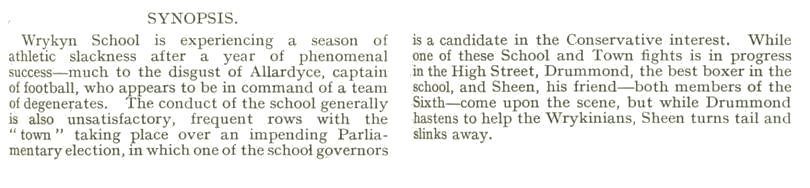

“Let’s go and chuck things at his door,” suggested Renford.

A move was made to the passage in which Sheen’s study was situated, and, with divers groans and howls, the junior day-room hove football boots and cricket stumps at the door.

The success of the meeting, however, was entirely neutralised by the fact that in the same passage stood the study of Rigby, the head of the house. Also Rigby was trying at the moment to turn into idiomatic Greek verse the words: “The Days of Peace and Slumberous Calm have fled,” and this corroboration of the statement annoyed him to the extent of causing him to dash out and sow lines among the revellers like some monarch scattering largesse. The junior day-room retired to its lair to inveigh against the brutal ways of those in authority and begin working off the commission it had received.

The howls in the passage were the first official intimation Sheen had received that his shortcomings were public property. The word “Funk!” shouted through his keyhole, had not unnaturally given him an inkling as to the state of affairs.

So Drummond had given him away, he thought. Probably he had told Linton the whole story the moment after he (Sheen) had met the latter at the door of the study. And perhaps he was now telling it to the rest of the house. Of all the mixed sensations from which he suffered as he went to his dormitory that night, one of resentment against Drummond was the keenest.

Sheen was in the fourth dormitory, where the majority of the day-room slept. He was in the position of a sort of extra house prefect, as far as the dormitory was concerned. It was a large dormitory, and Mr. Seymour had fancied that it might, perhaps, be something of a handful for a single prefect. As a matter of fact, however, Drummond, who was in charge, had shown early in the term that he was more than capable of managing the place single handed. He was popular and determined. The dormitory was orderly, partly because it liked him, principally because it had to be.

He had an opportunity of exhibiting his powers of control that night. When Sheen came in, the room was full. Drummond was in bed, reading his novel. The other ornaments of the dormitory were in various stages of undress.

As Sheen appeared, a sudden hissing broke out from the farther corner of the room. Sheen flushed, and walked to his bed. The hissing increased in volume and richness.

“Shut up that noise,” said Drummond, without looking up from his book.

The hissing diminished. Only two or three of the more reckless kept it up.

Drummond looked across the room at them.

“Stop that noise, and get into bed,” he said quietly.

The hissing ceased. He went on with his book again.

Silence reigned in dormitory four.

CHAPTER VI.

albert redivivus.

Y murdering in cold blood a large and respected family, and afterwards

depositing their bodies in a reservoir, one may gain, we are told, much

unpopularity in the neighbourhood of one’s crime; while robbing a church

will get one cordially disliked, especially by the vicar. But, to be really an outcast,

to feel that one has no friend in the world, one must break an important

public-school commandment.

Y murdering in cold blood a large and respected family, and afterwards

depositing their bodies in a reservoir, one may gain, we are told, much

unpopularity in the neighbourhood of one’s crime; while robbing a church

will get one cordially disliked, especially by the vicar. But, to be really an outcast,

to feel that one has no friend in the world, one must break an important

public-school commandment.

Sheen had always been something of a hermit. In his most sociable moments he had never had more than one or two friends; but he had never before known what it meant to be completely isolated. It was like living in a world of ghosts, or, rather, like being a ghost in a living world. That disagreeable experience of being looked through, as if one were invisible, comes to the average person, it may be, half a dozen times in his life. Sheen had to put up with it a hundred times a day. People who were talking to one another stopped when he appeared, and waited until he had passed on before beginning again. Altogether, he was made to feel that he had done for himself, that, as far as the life of the school was concerned, he did not exist.

There had been some talk, particularly in the senior day-room, of more active measures. It was thought that nothing less than a court-martial could meet the case. But the house prefects had been against it. Sheen was in the sixth, and, however monstrous and unspeakable might have been his acts, it would hardly do to treat him as if he were a junior. And the scheme had been definitely discouraged by Drummond, who had stated, without wrapping the gist of his remarks in elusive phrases, that in the event of a court-martial being held he would interview the president of the same and knock his head off. So Seymour’s had fallen back on the punishment which from their earliest beginnings the public schools have meted out to their criminals. They had cut Sheen dead.

In a way Sheen benefited from this excommunication. Now that he could not even play fives, for want of an opponent, there was nothing left for him to do but work. Fortunately, he had an object. The Gotford would be coming on in a few weeks, and the more work he could do for it, the better. Though Stanning was the only one of his rivals whom he feared, and though he was known to be taking very little trouble over the matter, it was best to run as few risks as possible. Stanning was one of those people who produce great results in their work without seeming to do anything for them.

So Sheen shut himself up in his study and ground grimly away at his books; and for exercise went for cross-country walks. It was a monotonous kind of existence. For the space of a week the only Wrykinian who spoke a single word to him was Bruce, the son of the Conservative candidate for Wrykyn: and Bruce’s conversation had been limited to two remarks. He had said, “You might play that again, will you?” and, later, “Thanks.” He had come into the music-room while Sheen was practising one afternoon, and had sat down, without speaking, on a chair by the door. When Sheen had played for the second time the piece which had won his approval, Bruce thanked him and left the room. As the solitary break in the monotony of the week, Sheen remembered the incident rather vividly.

Since the great rout of Albert and his minions outside Cook’s, things, as far as the seniors were concerned, had been quiet between school and town. Linton and Dunstable had gone to and from Cook’s two days in succession without let or hindrance. It was generally believed that, owing to the unerring way in which he had put his head in front of Drummond’s left on that memorable occasion, the scarlet-haired one was at present dry-docked for repairs. The story in the school—it had grown with the days—was that Drummond had laid the enemy out on the pavement with a sickening crash, and that he had still been there at, so to speak, the close of play. As a matter of fact, Albert was in excellent shape, and only an unfortunate previous engagement prevented him from ranging the streets near Cook’s as before. Sir William Bruce was addressing a meeting in another part of the town, and Albert thought it his duty to be on hand to boo.

In the junior portion of the school the feud with the town was brisk. Mention has been made of a certain St. Jude’s, between which seat of learning and the fags of Dexter’s and the School House there was a spirited vendetta.

Jackson, of Dexter’s, was one of the pillars of the movement. Jackson was

a calm-brow’d lad,

Yet mad, at moments, as a hatter,

and he derived a great deal of pleasure from warring against St. Jude’s. It helped him to enjoy his meals. He slept the better for it. After a little turn-up with a Judy he was fuller of that spirit of manly fortitude and forbearance so necessary to those whom Fate brought frequently into contact with Mr. Dexter. The Judies wore mortar-boards, and it was an enjoyable pastime sending these spinning into space during one of the usual rencontres in the High Street. From the fact that he and his friends were invariably outnumbered, there was a sporting element in these affairs, though occasionally this inferiority of numbers was the cause of his executing a scientific retreat with the enemy harassing his men up to the very edge of the town. This had happened on the last occasion. There had been casualties. No fewer than six house-caps had fallen into the enemy’s hands, and he himself had been tripped up and rolled in a puddle.

He burned to avenge this disaster.

“Coming down to Cook’s?” he said to his ally, Painter. It was just a week since the Sheen episode.

“All right,” said Painter.

“Suppose we go by the High Street,” suggested Jackson, casually.

“Then we’d better get a few more chaps,” said Painter.

A few more chaps were collected, and the party, numbering eight, set off for the town. There were present such stalwarts as Borwick and Crowle, both of Dexter’s, and Tomlin, of the School House, a useful man to have by you in an emergency. It was Tomlin who, on one occasion, attacked by two terrific champions of St. Jude’s in a narrow passage, had vanquished them both, and sent their mortar-boards miles into the empyrean, so that they were never the same mortar-boards again, but wore ever after a bruised and draggled look.

The expedition passed down the High Street without adventure, until, by common consent, it stopped at the lofty wall which bounded the playground of St. Jude’s.

From the other side of the wall came sounds of revelry, shrill squealings and shoutings. The Judies were disporting themselves at one of their weird games. It was known that they played touch-last, and Scandal said that another of their favourite recreations was marbles. The juniors at Wrykyn believed that it was to hide these excesses from the gaze of the public that the playground wall had been made so high. Eye witnesses, who had peeped through the door in the said wall, reported that what the Judies seemed to do mostly was to chase one another about the playground, shrieking at the top of their voices. But, they added, this was probably a mere ruse to divert suspicion. They had almost certainly got the marbles in their pockets all the time.

The expedition stopped, and looked itself in the face.

“How about buzzing something at them?” said Jackson earnestly.

“You can get oranges over the road,” said Tomlin in his helpful way.

Jackson vanished into the shop indicated, and reappeared a few moments later with a brown paper bag.

“It seems a beastly waste,” suggested the economical Painter.

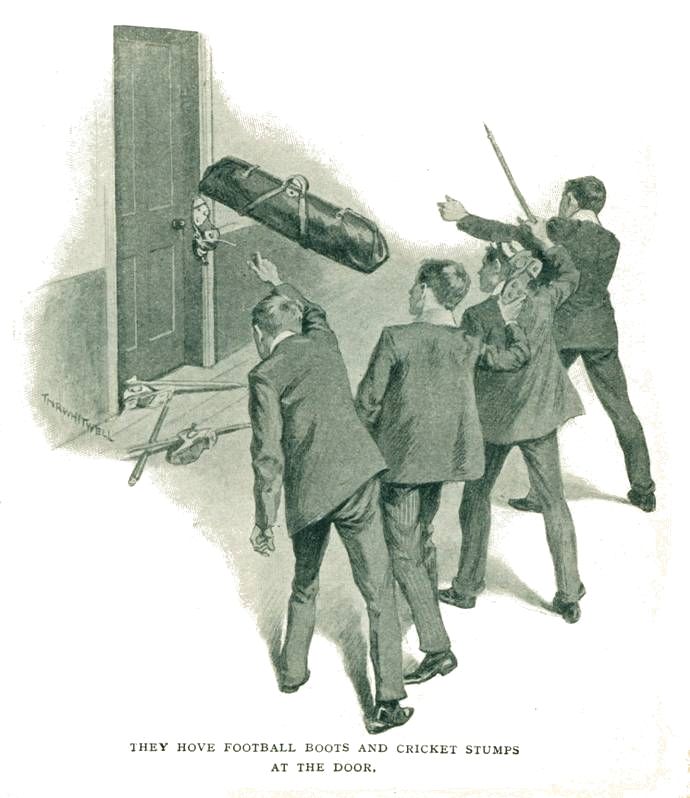

“That’s all right,” said Jackson, “they’re all bad. The man thought I was rotting him when I asked if he’d got any bad oranges, but I got them at last. Give us a leg up, some one.”

Willing hands urged him to the top of the wall. He drew out a green orange, and threw it.

There was a sudden silence on the other side of the wall. Then a howl of wrath went up to the heavens. Jackson rapidly emptied his bag.

“Got him!” he exclaimed, as the last orange sped on its way. “Look out, they’re coming!”

The expedition had begun to move off with quiet dignity, when from the doorway in the wall there poured forth a stream of mortar-boarded warriors, shrieking defiance. The expedition advanced to meet them.

As usual, the Judies had the advantage in numbers, and, filled to the brim with righteous indignation, they were proceeding to make things uncommonly warm for the invaders—Painter had lost his cap, and Tomlin three waistcoat buttons—when the eye of Jackson, roving up and down the street, was caught by a Seymour’s cap. He was about to shout for assistance when he perceived that the newcomer was Sheen, and refrained. It was no use, he felt, asking Sheen for help.

But just as Sheen arrived and the ranks of the expedition were beginning to give way before the strenuous onslaught of the Judies, the latter, almost with one accord, turned and bolted into their playground again. Looking round, Tomlin, that first of generals, saw the reason, and uttered a warning.

A mutual foe had appeared. From a passage on the left of the road there had debouched on to the field of action Albert himself and two of his band.

The expedition flew without false shame. It is to be doubted whether one of Albert’s calibre would have troubled to attack such small game, but it was the firm opinion of the Wrykyn fags and the Judies that he and his men were to be avoided.

The newcomers did not pursue them. They contented themselves with shouting at them. One of the band threw a stone.

Then they caught sight of Sheen.

Albert said, “Oo er!” and advanced at the double. His companions followed him.

Sheen watched them come, and backed against the wall. His heart was thumping furiously. He was in for it now, he felt. He had come down to the town with this very situation in his mind. A wild idea of doing something to restore his self-respect and his credit in the eyes of the house had driven him to the High Street. But now that the crisis had actually arrived, he would have given much to have been in his study again.

Albert was quite close now. Sheen could see the marks which had resulted from his interview with Drummond. With all his force Sheen hit out, and experienced a curious thrill as his fist went home. It was a poor blow from a scientific point of view, but Sheen’s fives had given him muscle, and it checked Albert. That youth, however, recovered rapidly, and the next few moments passed in a whirl for Sheen. He received a stinging blow on his left ear, and another which deprived him of his whole stock of breath, and then he was on the ground, conscious only of a wish to stay there for ever.

CHAPTER VII.

mr. joe bevan.

LMOST involuntarily he staggered up to receive another blow which sent him

down again.

LMOST involuntarily he staggered up to receive another blow which sent him

down again.

“That’ll do,” said a voice.

Sheen got up, panting. Between him and his assailant stood a short, sturdy man in a tweed suit. He was waving Albert back, and Albert appeared to be dissatisfied. He was arguing hotly with the newcomer.

“Now, you go away,” said that worthy, mildly, “just you go away.”

Albert gave it as his opinion that the speaker would do well not to come interfering in what didn’t concern him. What he wanted, asserted Albert, was a thick ear.

“Coming pushing yourself in,” added Albert querulously.

“You go away,” repeated the stranger. “You go away. I don’t want to have trouble with you.”

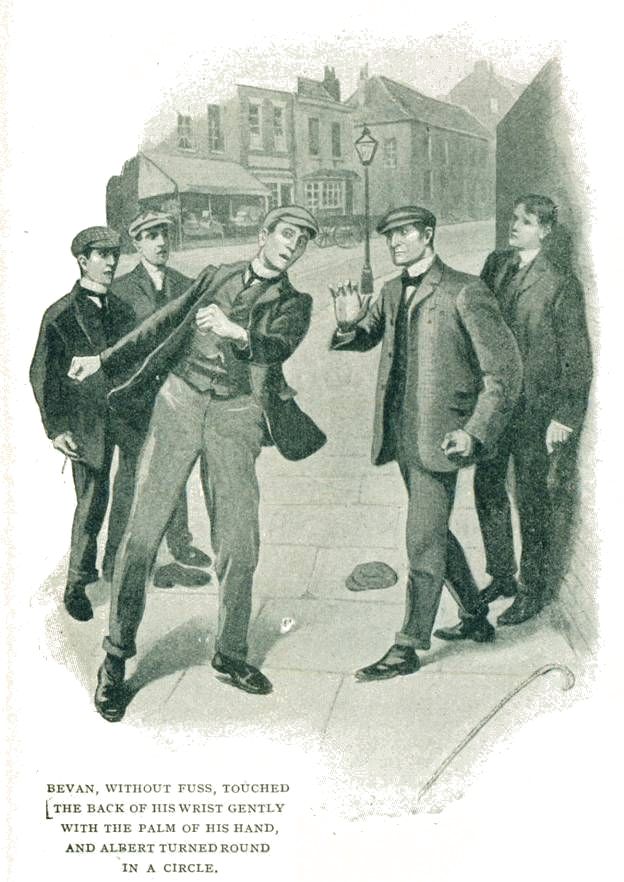

Albert’s reply was to hit out with his left hand in the direction of the speaker’s face. The stranger, without fuss, touched the back of Albert’s wrist gently with the palm of his right hand, and Albert, turning round in a circle, ended the manœuvre with his back towards his opponent. He faced round again irresolutely. The thing had surprised him.

“You go away,” said the other, as if he were making the observation for the first time.

“It’s Joe Bevan,” said one of Albert’s friends, excitedly.

Albert’s jaw fell. His freckled face paled.

“You go away,” repeated the man in the tweed suit, whose conversation seemed inclined to run in a groove.

This time Albert took the advice. His friends had already taken it.

“Thanks,” said Sheen.

“Beware,” said Mr. Bevan oracularly, “of entrance to a quarrel; but, being in, bear’t that th’ opposed may beware of thee. Always counter back when you guard. When a man shows you his right like that, always push out your hand straight. The straight left rules the boxing world. Feeling better, sir?”

“Yes, thanks.”

“He got that right in just on the spot. I was watching. When you see a man coming to hit you with his right like that, don’t you draw back. Get on top of him. He can’t hit you then.”

That feeling of utter collapse which is the immediate result of a blow in the parts about the waistcoat was beginning to pass away, and Sheen now felt capable of taking an interest in sublunary matters once more. His ear smarted horribly, and when he put up a hand and felt it the pain was so great that he could barely refrain from uttering a cry. But, however physically battered he might be, he was feeling happier and more satisfied with himself than he had felt for years. He had been beaten, but he had fought his best, and not given in. Some portion of his self-respect came back to him as he reviewed the late encounter.

Mr. Bevan regarded him approvingly.

“He was too heavy for you,” he said. “He’s a good twelve stone, I make it. I should put you at ten stone—say ten stone three. Call it nine stone twelve in condition. But you’ve got pluck, sir.”

Sheen opened his eyes at this surprising statement.

“Some I’ve met would have laid down after getting that first hit, but you got up again. That’s the secret of fighting. Always keep going on. Never give in. You know what Shakespeare says about the one who first cries, ‘Hold, enough!’ Do you read Shakespeare, sir?”

“Yes,” said Sheen.

“Ah, now he knew his business,” said Mr. Bevan enthusiastically. “There was ringcraft, as you may say. He wasn’t a novice.”

Sheen agreed that Shakespeare had written some good things in his time.

“That’s what you want to remember. Always keep going on, as the saying is. I was fighting Dick Roberts at the National—an American, he was, from San Francisco. He come at me with his right stretched out, and I think he’s going to hit me with it, when blessed if his left don’t come out instead, and, my Golly! it nearly knocked a passage through me. Just where that fellow hit you, sir, he hit me. It was just at the end of the round, and I went back to my corner. Jim Blake was seconding me. ‘What’s this, Jim?’ I says, ‘is the man mad, or what?’ ‘Why,’ he says, ‘he’s left-handed, that’s what’s the matter. Get on top of him.’ ‘Get on top of him? I says. ‘My Golly, I’ll get on top of the roof if he’s going to hit me another of those.’ But I kept on, and got close to him, and he couldn’t get in another of them, and he give in after the seventh round.”

“What competition was that?” asked Sheen.

Mr. Bevan laughed. “It was a twenty-round contest, sir, for seven-fifty aside and the Light Weight Championship of the World.”

Sheen looked at him in astonishment. He had always imagined professional pugilists to be bullet-headed and beetle-browed to a man. He was not prepared for one of Mr. Joe Bevan’s description. For all the marks of his profession that he bore on his face, in the shape of lumps and scars, he might have been a curate. His face looked tough, and his eyes harboured always a curiously alert, questioning expression, as if he were perpetually “sizing up” the person he was addressing. But otherwise he was like other men. He seemed also to have a pretty taste in Literature. This, combined with his strong and capable air, attracted Sheen. Usually he was shy and ill at ease with strangers. Joe Bevan he felt he had known all his life.

“Do you still fight?” he asked.

“No,” said Mr. Bevan, “I gave it up. A man finds he’s getting on, as the saying is, and it don’t do to keep at it too long. I teach and I train, but I don’t fight now.”

A sudden idea flashed across Sheen’s mind. He was still glowing with that pride which those who are accustomed to work with their brains feel when they have gone honestly through some labour of the hands. At that moment he felt himself capable of fighting the world and beating it. The small point, that Albert had knocked him out of time in less than a minute, did not damp him at all. He had started on the right road. He had done something. He had stood up to his man till he could stand no longer. An unlimited vista of action stretched before him. He had tasted the pleasure of the fight, and he wanted more.

Why, he thought, should he not avail himself of Joe Bevan’s services to help him put himself right in the eyes of the house? At the end of the term, shortly before the Public Schools’ Competitions at Aldershot, inter-house boxing cups were competed for at Wrykyn. It would be a dramatic act of reparation to the house if he could win the Light-Weight cup for it. His imagination, jumping wide gaps, did not admit the possibility of his not being good enough to win it. In the scene which he conjured up in his mind he was an easy victor. After all, there was the greater part of the term to learn in, and he would have a Champion of the World to teach him.

Mr. Bevan cut in on his reflections as if he had heard them by some process of wireless telegraphy.

“Now, look here, sir,” he said, “you should let me give you a few lessons. You’re plucky, but you don’t know the game as yet. And boxing’s a thing every one ought to know. Supposition is, you’re crossing a field or going down a street with your sweetheart or your wife——”

Sheen was neither engaged nor married, but he let the point pass.

—“And up comes one of these hooligans, as they call ’em. What are you going to do if he starts his games? Why, nothing, if you can’t box. You may be plucky, but you can’t beat him. And if you beat him, you’ll get half murdered yourself. What you want to do is to learn to box, and then what happens? Why, as soon as he sees you shaping, he says to himself, ‘Hullo, this chap knows too much for me. I’m off,’ and off he runs. Or supposition is, he comes for you. You don’t mind. Not you. You give him one punch in the right place, and then you go off to your tea, leaving him lying there. He won’t get up.”

“I’d like to learn,” said Sheen. “I should be awfully obliged if you’d teach me. I wonder if you could make me any good by the end of the term. The House Competitions come off then.”

“That all depends, sir. It comes easier to some than others. If you know how to shoot your left out straight, that’s as good as six months’ teaching. After that it’s all ring-craft. The straight left beats the world.”

“Where shall I find you?”

“I’m training a young chap—eight stone seven, and he’s got to get down to eight stone four, for a bantam weight match—at an inn up the river here. I daresay you know it, sir. Or any one would tell you where it is. The ‘Blue Boar,’ it’s called. You come there any time you like to name, sir, and you’ll find me.”

“I should like to come every day,” said Sheen. “Would that be too often?”

“Oftener the better, sir. You can’t practise too much.”

“Then I’ll start next week. Thanks very much. By the way, I shall have to go by boat, I suppose. It isn’t far, is it? I’ve not been up the river for some time. The school generally goes down stream.”

“It’s not what you’d call far,” said Bevan. “But it would be easier for you to come by road.”

“I haven’t a bicycle.”

“Wouldn’t one of your friends lend you one?”

Sheen flushed. It was hardly likely.

“No, I’d better come by boat, I think. I’ll turn up on Tuesday at about five. Will that suit you?”

“Yes, sir. That will be a good time. Then I’ll say good-bye, sir, for the present.”

Sheen went back to his house in a different mood from the one in which he had left it. He did not care now when the other Seymourites looked through him.

In the passage he met Linton, and grinned pleasantly at him.

“What the dickens was that man grinning at?” said Linton to himself. “I must have a smut or something on my face.”

But a close inspection in the dormitory looking-glass revealed no blemish on his handsome features.

Sheen had smiled at his thoughts.

CHAPTER VIII.

a naval battle and its consequences.

HAT a go is life!

HAT a go is life!

Let us examine the case of Jackson, of Dexter’s. O’Hara, who had left Dexter’s at the end of the summer term, had once complained to Clowes of the manner in which his housemaster treated him, and Clowes had remarked in his melancholy way that it was nothing less than a breach of the law that Dexter should persist in leading a fellow a dog’s life without a dog licence for him.

That was precisely how Jackson felt on the subject.

Things became definitely unbearable on the day after Sheen’s interview with Mr. Joe Bevan.

’Twas morn—to begin at the beginning—and Jackson sprang from his little cot to embark on the labours of the day. Unfortunately, he sprang ten minutes too late, and came down to breakfast about the time of the second slice of bread and marmalade. Result, a hundred lines. Proceeding to school, he had again fallen foul of his housemaster—in whose form he was—over a matter of unprepared Livy. As a matter of fact, Jackson had prepared the Livy. Or, rather, he had not absolutely prepared it; but he had meant to. But it was Mr. Templar’s preparation, and Mr. Templar was short-sighted. Any one will understand, therefore, that it would have been simply chucking away the gifts of Providence if he had not gone on with the novel which he had been reading up till the last moment before prep.-time, and had brought along with him accidentally, as it were. It was a book called A Spoiler of Men, by Mr. Richard Marsh, and was thick with crime and desparate deed. It was Hot Stuff. Much better than Livy. . . .

Lunch Score—Two hundred lines.

During lunch he had the misfortune to upset a glass of water. Pure accident, of course, but there it was, don’t you know, all over the table.

Mr. Dexter had called him:

(a) clumsy;

(b) a pig;

and had given him

(1) Advice—“You had better be careful, Jackson.”

(2) A present—“Two hundred lines, Jackson.”

On the match being resumed at two o’clock, with four hundred lines on the score-sheet, he had played a fine, free game during afternoon school, and Mr. Dexter, who objected to fine, free games—or, indeed, any games—during school hours, had increased the total to six hundred, when stumps were drawn for the day.

So on a bright, sunny Saturday afternoon, when he should have been out in the field cheering the house team on to victory against the School House, Jackson sat in the junior day-room at Dexter’s copying out portions of Virgil, Æneid Two.

To him, later on in the afternoon, when he had finished half his task, entered Painter, with the news that Dexter’s had taken thirty points off the School House just after half-time.

“Mopped them up,” said the terse and epigrammatic Painter. “Made rings round them. Haven’t you finished yet? Well, chuck it, and come out.”

“What’s on?” asked Jackson.

“We’re going to have a boat race.”

“Pile it on.”

“We are, really. Fact. Some of these School House kids are awfully sick about the match, and challenged us. That chap Tomlin thinks he can row.”

“He can’t row for nuts,” said Jackson. “He doesn’t know which end of the oar to shove into the water. I’ve seen cats that could row better than Tomlin.”

“That’s what I told him. At least, I said he couldn’t row for toffee, so he said all right, I bet I can lick you, and I said I betted he couldn’t, and he said all right, then, let’s try, and then the other chaps wanted to join in, so we made an inter-house thing of it. And I want you to come and stroke us.”

Jackson hesitated. Mr. Dexter, setting the lines on Friday, had certainly said that they were to be shown up “to-morrow evening.” He had said it very loud and clear. Still, in a case like this. . . . After all, by helping to beat the School House on the river he would be giving Dexter’s a leg-up. And what more could the man want?

“Right ho,” said Jackson.

Down at the School boat-house the enemy were already afloat when Painter and Jackson arrived.

“Buck up,” cried the School House crew.

Dexter’s embarked, five strong. There was room for two on each seat. Jackson shared the post of stroke with Painter. Crowle steered.

“Ready?” asked Tomlin from the other boat.

“Half a sec.,” said Jackson. “What’s the course?”

“Oh, don’t you know that yet? Up to the town, round the island just below the bridge,—the island with the croquet ground on it, you know—and back again here. Ready?”

“In a jiffy. Look here, Crowle, remember about steering. You pull the right line if you want to go to the right and the other if you want to go to the left.”

“All right,” said the injured Crowle. “As if I didn’t know that.”

“Thought I’d mention it. It’s your fault. Nobody could tell by looking at you that you knew anything except how to eat. Ready, you chaps?”

“When I say ‘Three,’ ” said Tomlin.

It was a subject of heated discussion between the crews for weeks afterwards whether Dexter’s boat did or did not go off at the word “Two.” Opinions were divided on the topic. But it was certain that Jackson and his men led from the start. Pulling a good, splashing stroke which had drenched Crowle to the skin in the first thirty yards, Dexter’s boat crept slowly ahead. By the time the island was reached, it led by a length. Encouraged by success, the leaders redoubled their already energetic efforts. Crowle sat in a shower-bath. He was even moved to speech about it.

“When you’ve finished,” said Crowle.

Jackson, intent upon repartee, caught a crab, and the School House drew level again. The two boats passed the island abreast.

Just here occurred one of those unfortunate incidents. Both crews had quickened their stroke until the boats had practically been converted into submarines, and the rival coxswains were observing bitterly to Space that this was jolly well the last time they ever let themselves in for this sort of thing, when round the island there hove in sight a flotilla of boats, directly in the path of the racers.

There were three of them, and not even the spray which played over them like a fountain could prevent Crowle from seeing that they were manned by Judies. Even on the river these outcasts wore their mortar-boards.

“Look out!” shrieked Crowle, pulling hard on his right line. “Stop rowing, you chaps. We shall be into them.”

At the same moment the School House oarsmen ceased pulling. The two boats came to a halt a few yards from the enemy.

“What’s up?” panted Jackson, crimson from his exertions. “Hullo, it’s the Judies!”

Tomlin was parleying with the foe.

“Why the dickens can’t you keep out of the way? Spoiling our race. Wait till we get ashore.”

But the Judies, it seemed, were not prepared to wait even for that short space of time. A miscreant, larger than the common run of Judy, made a brief, but popular, address to his men.

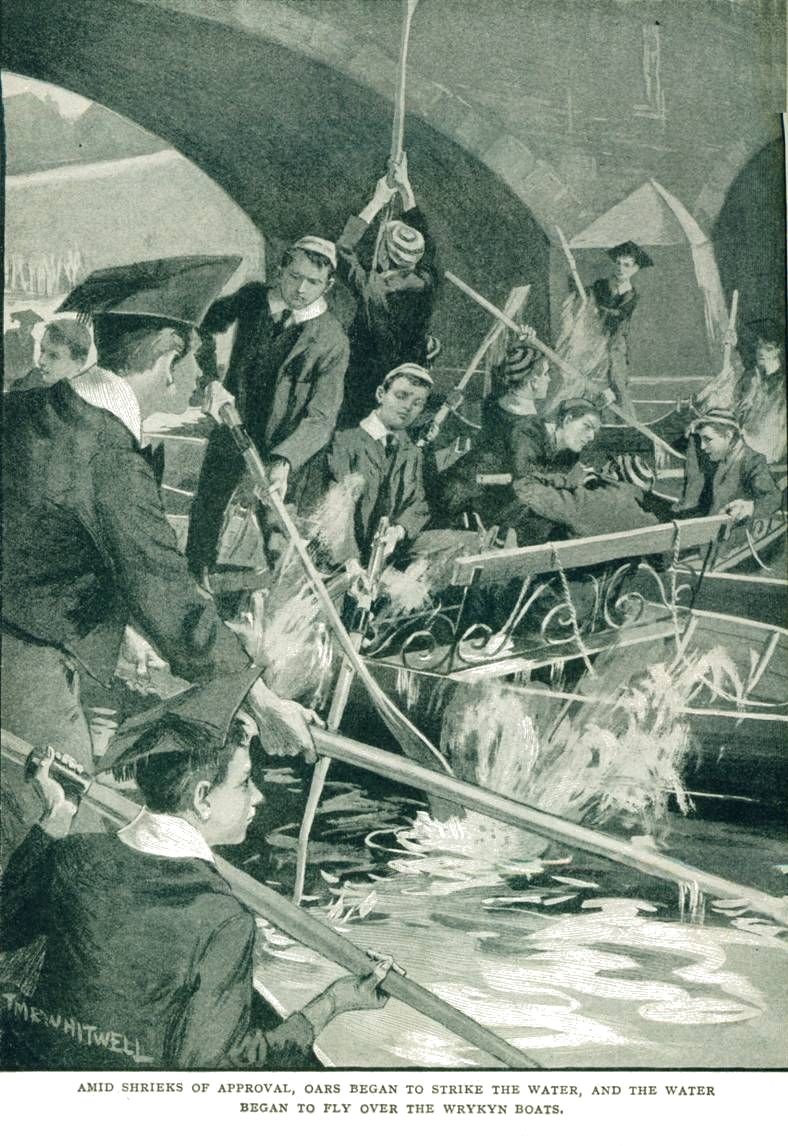

“Splash them!” he said.

Instantly, amid shrieks of approval, oars began to strike the water, and the water began to fly over the Wrykyn boats, which were now surrounded. The latter were not slow to join battle with the same weapons. Homeric laughter came from the bridge above. The town bridge was a sort of loafers’ club, to which the entrance fee was a screw of tobacco, and the subscription an occasional remark upon the weather. Here gathered together day by day that section of the populace which resented it when they “asked for employment, and only got work instead.” From morn till eve they lounged against the balustrades, surveying nature, and hoping it would be kind enough to give them some excitement that day. An occasional dog-fight found in them an eager audience. No runaway horse ever bored them. A broken-down motor-car was meat and drink to them. They had an appetite for every spectacle.

When, therefore, the water began to fly from boat to boat, kind-hearted men fetched their friends from neighbouring public-houses and craned with them over the parapet, observing the sport and commenting thereon. It was these comments that attracted Mr. Dexter’s attention. When, cycling across the bridge, he found the south side of it entirely congested, and heard raucous voices urging certain unseen “little ’uns” now to “go it” and anon to “vote for Pedder,” his curiosity was aroused. He dismounted and pushed his way through the crowd until he got a clear view of what was happening below.

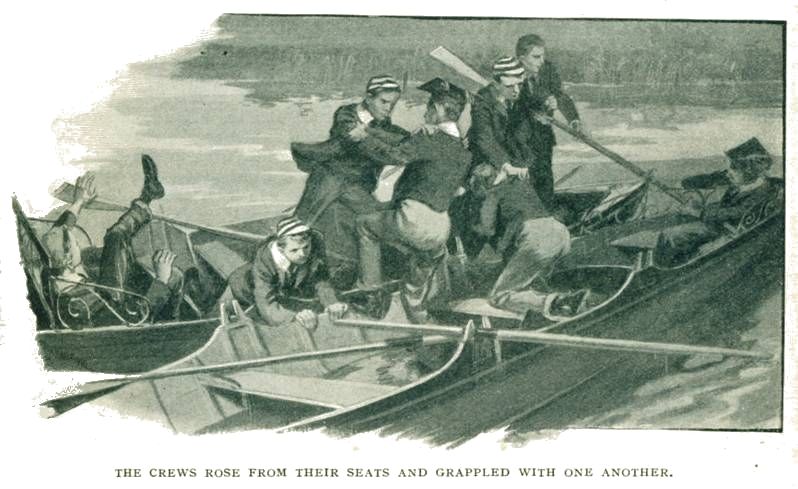

He was just in time to see the most stirring incident of the fight. The biggest of the Judy boats had been propelled by the current nearer and nearer to the Dexter Argo. No sooner was it within distance than Jackson, dropping his oar, grasped the side and pulled it towards him. The two boats crashed together and rocked violently as the crews rose from their seats and grappled with one another. A hurricane of laughter and applause went up from the crowd upon the bridge.

The next moment both boats were bottom upwards and drifting sluggishly down towards the island, while the crews swam like rats for the other boats.

Every Wrykinian had to learn to swim before he was allowed on the river; so that the peril of Jackson and his crew was not extreme: and it was soon speedily evident that swimming was also part of the Judy curriculum, for the shipwrecked ones were soon climbing drippingly on board the surviving ships, where they sat and made puddles, and shrieked defiance at their antagonists.

This was accepted by both sides as the end of the fight, and the combatants parted without further hostilities, each fleet believing that the victory was with them.

And Mr. Dexter, mounting his bicycle again, rode home to tell the headmaster.

That evening, after preparation, the headmaster held a reception. Among distinguished visitors were Jackson, Painter, Tomlin, Crowle, and six others.

On the Monday morning the headmaster issued a manifesto to the school after prayers. He had, he said, for some time entertained the idea of placing the town out of bounds. He would do so now. No boy, unless he was a prefect, would be allowed till further notice to cross the town bridge. As regarded the river, for the future boating Wrykinians must confine their attentions to the lower river. Nobody must take a boat up-stream. The school boatman would have strict orders to see that this rule was rigidly enforced. Any breach of these bounds would, he concluded, be punished with the utmost severity.

The headmaster of Wrykyn was not a hasty man. He thought before he put his foot down. But when he did, he put it down heavily.

Sheen heard the ultimatum with dismay. He was a law-abiding person, and here he was, faced with a dilemma that made it necessary for him to choose between breaking school rules of the most important kind or pulling down all the castles he had built in the air before the mortar had had time to harden between their stones.

He wished he could talk it over with somebody. But he had nobody with whom he could talk over anything. He must think it out for himself.

He spent the rest of the day thinking it out, and by nightfall he had come to his decision.

Even at the expense of breaking bounds and the risk of being caught at it, he must keep his appointment with Joe Bevan. It would mean going to the town landing-stage for a boat, thereby breaking bounds twice over.

But it would have to be done.

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums