Chapter 27

The Thief Explains

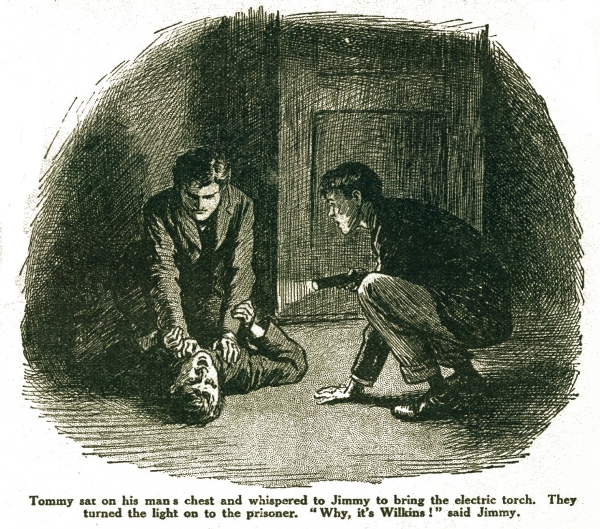

THE struggle was short and sharp. Taken by surprise, the unknown looter of play-boxes made very little resistance after the first half-minute. His head had come into contact, as he fell, with the edge of a box, and this had discouraged him as much as anything.

The whole affair, except for the crack of the head on the box and the quick breathing of the three as they struggled, had been conducted with perfect quiet. The thief was just as anxious as were Jimmy and Tommy not to be heard.

Tommy sat on the man’s chest and whispered to Jimmy to bring the torch, which lay some feet away. They turned the light on to the prisoner.

“Why, it’s Wilkins!” said Jimmy.

Wilkins was the overgrown youth who cleaned the knives and boots of the house. Jimmy and Tommy had sometimes given him twopence to fetch them biscuits and jam from the village after lock-up.

“Is that you, Mr. Stewart?” whined the prostrate knife-and-boot expert. “Let me up, Mr. Stewart. I won’t never do it again. Give a feller a chance, Mr. Stewart.”

Tommy rapped him on the top of the head with his knuckles.

“Not so much of it,” he said severely. “What were you playing at with these boxes? That’s what we want to know? Buck up and tell us, or I’ll jolly well screw your neck.”

“Oh, Mr. Armstrong,” said Wilkins, “do let me up. Don’t be ’arsh on a feller, Mr. Armstrong. I promise faithful it shan’t ’appen again, Mr. Armstrong. I——”

“Less of it—less of it,” said Tommy. “Good heavens! The chap’s a perfect gas-bag. You lie still for a bit and don’t talk. I want to discuss this matter. If you jaw again till I tell you you may I’ll smother you.”

Wilkins subsided with a sniff.

“Now then, Jimmy,” said Tommy in a brisk undertone, “what’s to be done about this?”

“Oh, let him go,” said Jimmy. Now that the excitement was over he was tired of the whole thing, and wanted to get safely back to bed. Besides, though he knew that Wilkins deserved whatever he might get, he always felt sorry for anybody who was in a tight place. He did not wish to treat Wilkins with the severity which a stern moralist would have considered proper.

“Oh, thank yer, Mr. Stewart, thank—ow!”

The last word was the result of a vigorous smack on the head from Tommy.

“Keep quiet, you worm!” said Tommy. “Reserve your remarks till this court calls upon you to speak. By Jingo, if you interrupt again I’ll give you a jab in the bazooka, which’ll make you see stars for the rest of the night.”

Another sniff was the reply. Tommy turned to Jimmy again.

“Let him go?” he said. “But, dash it, we’ve only just caught him.”

“I know. But it’s no good getting the poor beast into the dickens of a row. If you let him go now he’ll probably turn over a what-d’you call-it—new leaf, I mean. Let’s make him give back the things he’s bagged, and then let him go.”

Tommy reflected.

“All right,” he said at last. “I suppose we may as well. It’ll be a lesson to him. And, by Jove, I forgot! There’s another reason. Tell you later.”

It had suddenly dawned upon Tommy that his own and Jimmy’s position in this matter was more than a little questionable. True, they had caught the thief. But they had broken out of their dormitory and climbed the locked railing at the end of the passage to do it; and there was no doubt that, after the authorities had made it warm for Wilkins for stealing, they would proceed to make it more than a little warm for the captors for breaking school rules. This had the effect of quenching Tommy’s zeal for arresting malefactors. In the detective stories the detective does not have to think whether he will get caned or given lines after he has captured his man. He can concentrate his mind on the capture. This, thought Tommy, gives him an unfair advantage over the amateur detective at school.

“All right,” he said, “we’ll let you go. But you’ve jolly well got to put back everything you’ve bagged. You can leave them somewhere in here where the chaps will find them.”

“Oh, thank yer, thank yer, Mr. Armstrong and Mr. Stewart; but I’ve ate the chocolates.”

“Well, you needn’t worry about those, then. I only hope they made you ill. But all the rest of the things—see?”

“Yes, Mr. Armstrong.”

“To-morrow morning, first thing.”

“Yes, Mr. Armstrong.”

“And now,” said Tommy, “before I let you up, you can go ahead and tell us how you managed to open these boxes. That’s what’s been puzzling me.”

“I was led away, Mr. Armstrong.”

“Don’t be an ass. That doesn’t account for it. You can’t open a locked play-box simply by being led away,”

“It was the chap wot led me away wot give me the key.”

“What key?”

“He called it a skellington key.”

“Skeleton key! Ah, that accounts for it. Now we are getting hold of something, as the bulldog said when he bit the tramp’s Sunday trousers.”

Wilkins laughed respectfully, but was discouraged with a rap on the head.

“Don’t giggle there like a hyæna,” said Tommy sternly. “What you’ve got to do is to fix your mind on the painful details, and tell me them in a low, clear voice. Who’s this chap you’re talking about—the chap who gave you the key? And what on earth did he give you the key for?”

“He wanted me to find him something in Mr. Stewart’s box——”

“What!” cried Jimmy, suddenly interested.

“Yes, Mr. Stewart. He said it was a small blue stone, what looked like a piece of sealing-wax, and I was to take it from your box and he’d give me half a crown for it. And he give me the key. He said it would open any box—it didn’t matter what sort of lock it was; and, being easily led away, I tried some of the boxes, and——”

“By Jove, Jimmy, then you were right after all!” said Tommy excitedly. “That rummy stone was really worth something. I thought you were only piling it on about it for a lark. By Jove, this is getting interesting! Go on, you blighter. Who was the man?”

“I ’adn’t never set eyes on him before, Mr. Armstrong.”

“Was it a biggish, clean-shaven man, with queer-looking eyes?” asked Jimmy. It was the nearest he could get to a description of Marshall.

“No, Mr. Stewart. He was a stout man with a moustache. He talked rather slow and pleasant-like. Sort of like a cat, he reminded me.”

“Ferris!” cried Jimmy. So this was a sample of Ferris’s methods! He could not help admitting that they were subtler than Marshall’s, as Ferris himself had said. But for the accident of the stone having passed in the first instance out of Jimmy’s possession it would have been in the play-box, and the move would have been successful. Jimmy felt that Ferris was more to be feared than Marshall. Ferris could strike where Marshall could not. Wilkins’s comparison of him to a cat struck him as particularly apt. It was that smooth, cat-like quality in him which made him so formidable as a foe.

“Have you got the key?” asked Tommy. “Oh, it’s in that lock now, is it? Well, I’ll keep it, I think. It’s a useful thing to have about the house. Now,” he said, rising, “you can clear out. We needn’t detain you.”

Wilkins began to utter profuse expressions of gratitude, but was cut short. He slid noiselessly from the room; and Tommy and Jimmy, bearing the electric torch to light their way, returned hurriedly to their dormitory.

“I say, Jimmy,” said Tommy, sitting on his bed, “this has been a bit of an eye-opener. I’d no notion you weren’t simply rotting about that blue stone of yours. Do you mean to say these fellows really are after it?”

Jimmy related briefly the events which had taken place in the cottage. Tommy’s eyes bulged as he listened.

“My word!” he gasped.

There was a silence while he rearranged his view on the whole matter, and examined it afresh in the light of this new information.

“Do you mean to say they shot at you?” he said at last.

Jimmy nodded.

“I say!” said Tommy.

“But, dash it, you ought to do something,” he went on. “I mean it’s dangerous.”

“It is a bit,” agreed Jimmy with a short laugh. “But what can I do?”

“Why, tell the—No, you can’t do that. Not tell the police, I mean. They wouldn’t believe you any more than I did.”

“No.”

“The queer part about it is that these fellows are after the wrong man the whole time. They really don’t want you at all, if they only knew it. They want Spinder; he’s got the stone.”

“I know he has—somewhere. I wish I knew where.”

Tommy leaped excitedly from his bed.

“I know where it is! Great Scott, of course. Do you remember, when we were hiding in his study, seeing him——”

“I couldn’t see him from where I was.”

“Nor you could. Well, I saw him go to one of the shelves, pull out a book, and take out something from behind it. It was the stone, of course. I can see that now. Well, when he was ragging me in his room yesterday, the Head sent for him, and I was left alone. So I nipped to the shelf and began lugging out the books. I’d just pulled out the seventh, and felt there was something small and hard behind it, when he came back, and I had only just time to shove the book in again.”

It was Jimmy’s turn to be excited.

“Are you sure?” he said eagerly.

“Absolutely certain.”

Jimmy sprang to his feet.

“Let’s go down and look,” he said.

They left the room and made the difficult journey a second time, creeping stealthily down the stairs and along the corridor to the master’s study.

They stopped at the door. There was no light underneath it. Jimmy seized the handle, turned it gently, and pushed. The door did not open. He pushed again, but with no result.

“Locked,” he whispered.

“He must have started locking it after that fight between Sam and the man,” said Tommy. “We’d better get back.”

“Yes; we must look out for another chance.”

They crept upstairs again to their dormitory.

Chapter 28

The Great Football Match

THE next day was the day of the football match. Most of the members of the team spent their spare time during the morning practising shooting goals with crumpled-up balls of paper, and Bellamy, who was to keep goal, being a youth who believed in taking no chances, was observed sitting in a corner studying “Hints to Young Goal-keepers,” by a Scottish International. He thought it might contain one or two tips which would come in useful in the heat of the struggle.

As Jimmy was standing in the road by the school that morning, a village boy addressed him.

“Could yoou tell Oi——”

He held out a note.

“Let’s have a look,” said Jimmy. He glanced at the note. It was addressed to himself, written in pencil in a hand that was strange to him. “That’s all right,” he said. “It’s for me. Thanks.”

He opened it. It was from Sam Burrows.

“Mr. Stewart,” it ran. “Sir—Must see you if possible to-day. Very important. Hear you are playing football at the College to-day. Should respectfully request you meet me at the first mile-stone as you leave College at five sharp. Please be there, as matter is very important.—SAML. BURROWS.”

Jimmy stared at the note thoughtfully. He re-read it. What could this thing be about which Sam wished to see him? He wished he had given a hint in the note, but recollected that it might not have been safe. The note was written on a scrap of paper, not enclosed in an envelope.

He had not seen Sam since that day when he had told him of the loss of the stone, and he had wondered at the latter’s silence. Where had he been all this time? Why had he sent no message? However, he would soon know. He resolved to bicycle to the match, instead of riding with the others in the brake. That would give him an opportunity of slipping away. He could ride on and catch them up after he had seen Sam. Or he could slip away before the brake started. Bowdon would probably ask him to tea. He could go to tea and come away early. The team would know where he had gone, and would not expect to see him again till they returned to the school.

He showed the note to Tommy. Tommy, greatly interested, suggested that he should come too; but Jimmy thought not. Sam would prefer to see him alone.

“I tell you what,” said Tommy, “I’ve been thinking this business over, and I see the force of what you told me that fellow Marshall said in the cottage about the difficulty of getting at a chap at school. I think you’re all right as long as you stick to the rest of us. You’re sure there’s no risk of them getting you if you come home alone?”

“Oh, no. They wouldn’t tackle me while Sam was there. Sam’s got a revolver.”

“How about the air-gun?”

“They won’t get him that way again. There’s no cover by that milestone. They couldn’t hide near enough to shoot. Besides, it’s pretty dark about five o’clock. They couldn’t see to aim from a distance. I shall be all right.”

“I hope so,” said Tommy doubtfully. “I wish you’d let me come.”

The match was due to begin at half-past two. It was a dry, cold day, with a rather strong wind blowing across the ground. The Marleigh team took the field, somewhat nervous. They were playing away from home—which is always a handicap to a football team—and the jaunty confidence of the College boys tended to make them think less of themselves. The only unconcerned member of the eleven was Bellamy, who perused his “Hints to Young Goal-keepers” till the last possible moment, putting the book away in his great-coat pocket with reluctance when the teams began to strip.

“I’d only got to page eighty-one,” he confided to Jimmy in an aggrieved tone. “Still, I’ve got hold of some useful information. I think we shall be all right.”

He was the only one of the eleven who did think so. The rest were unmistakably nervous. Even Jimmy felt doubtful, and Tommy was remarkably subdued.

The Alderton team filed on to the ground, looking very trim and workmanlike. Bowdon came across and shook hands with Jimmy.

“Hullo!” he said. “Feeling fit?”

“Pretty well, thanks. Where are you playing?”

“Outside right. Where are you?”

“Right back.”

“Oh, then we shan’t meet, I suppose. By the way, you ought to see O’Connell. He’s a different man. You seem to have knocked all the side out of him. It was a splendid thing for him. Come in and have some tea in my study afterwards?”

“Thanks awfully.”

“Good. Oh, I say, how’s your pal—the black man who recited? All right?”

“Splendid. Hullo, they’re just going to start.”

“So they are. Well, see you afterwards.”

“Right ho. Thanks.”

Bowdon trotted to his place, and the referee blew his whistle.

It was evident from the first that the College team thought little of the capabilities of their opponents. They started with a cheerful confidence in their own powers, which had the effect of upsetting the Marleigh eleven still further. A little tricky passing, and the ball was in the visitors’ territory. Bowdon, racing down on the right, tricked Tommy, made for the corner flag, and centred. The Alderton centre forward steadied himself for a moment, then banged the ball hard and tight into the corner of the net. Alderton was one up after two minutes play.

Bellamy, the goal-keeper, had stood stock still while the shot was being made.

“For goodness’ sake get to them, Bellamy,” said Jimmy. “You didn’t move.”

“I know,” said Bellamy indignantly. “It was all that book. It’s a beastly fraud. That was one of the cases mentioned in the second chapter. By right that man ought to have shot along dotted line A to B, clean into my hands. Instead of which he let me down by sending the ball into the corner. I’m going to forget that book for the rest of the game.”

“I should,” said Jimmy. “We don’t want to get licked by double figures.”

The early goal had two effects. It increased the self-confidence of the Alderton team to just beyond that point where self-confidence is a good thing; and it stung the Marleigh eleven into activity. The feeling of strangeness and nervousness wore off, leaving only a determination to play their own game and win if they could.

A stout attack by the forwards was stopped by the Alderton backs, and the ball returned to the Marleigh half. The College forwards began to attack again. But their over-confidence robbed the movement of all its force. Instead of going hard for the goal they wasted time in exhibition passing and trick-work. It baffled the Marleigh halves, but Tommy and Jimmy, lying behind them, found no difficulty in tackling. The fact was that the College team was suffering the curious effect of being too scientific. Every year in the cup ties one sees instances of what is plainly the less skilful team beating by rugged, straightforward play a team that plays too clever a game.

This was what happened now. The College forwards did surprising things with the ball. They passed with the greatest neatness, and tricked their men time after time. They did everything, in fact, but score goals. Whereas Marleigh, when they attacked, did it with a direct purpose which was infinitely more effective.

After twenty minutes’ play, Morrison, running straight through in the centre, slung the ball across to Jarvis on the left. Jarvis sprinted straight down the touchline, dodged the back, and centred. Morrison got to the ball just before the goal-keeper, and headed it through. The scores were now equal.

This unexpected reverse sobered the College team. Their forwards abandoned their exhibition tactics, and endeavoured to get through. But Marleigh was now on its mettle. Tommy and Jimmy at back were not to be passed. Time after time they cleared with long kicks which gave their forward line chances of which they availed themselves. The scientific College forwards were knocked off the ball again and again till their combination became ragged and uncertain. The college goal-keeper was kept busy.

Just before half-time, stopping a hot shot from Morrison, he could not get rid of the ball at once, and Binns, who had come up from centre half to join in the attack, rushed in and hustled him over the line.

Marleigh crossed over at half-time a goal to the good.

Alderton never recovered the lost ground. Bowdon made some good runs on his wing, but the team, as a team, were all to pieces. They passed wildly. They lost their heads, and dribbled when they should have passed. The wind, which was now blowing straight down the ground, helped Tommy and Jimmy with their clearing kicks; and when, shortly after the restart, Sloper scored with a long dropping shot, the thing became a rout. Marleigh had all the game. Bellamy was only called upon to save twice more, on which occasions, relying on his own methods, he kept the ball out with great success. Ten minutes later Morrison shot the fourth goal. And when the whistle blew the score was six to one in favour of Marleigh. The College team left the field with rather less jauntiness than they had entered it. Marleigh strolled off with a careless air, as if that sort of thing was a mere nothing to them.

Tommy went home with the others in the brake, leaving Jimmy with Bowdon. He was not easy in his mind. He was vaguely afraid. Jimmy should have taken him to the rendezvous in case of accidents.

He went to his study and waited. He waited for what seemed to him quite a long time. Surely, he thought, Jimmy should have been back by now. He looked at his watch. A quarter-past six. It was queer.

Half-past six came and went, and a quarter to seven. Tommy began to feel more than vaguely uneasy. He was almost certain now that something must have happened.

Five to seven.

He went into the road, and looked out along it.

There were no signs of Jimmy. It was empty.

(Another absorbing instalment of this serial next week.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums