Collier’s Weekly, November 12, 1921

SALLY cut short a holiday in France, and Ginger Kemp’s proposal, to reach Detroit for the opening of her fiancé’s play. She found it dying in its last rehearsals. Her brother Fillmore persuaded her to buy it and make him manager. This saved its life. Sally had an unexpected encounter with Bruce Carmyle, Ginger Kemp’s cousin, who seemed more interested in seeing her than America. Ginger, he said, had disappeared.

VI (Chapter 8 Continued)

DAYLIGHT brought no comforting answer to the question about Ginger Kemp. Breakfast failed to manufacture an easy mind. Sally got off the train at the Grand Central Terminal in a state of remorseful concern. She declined the offer of Mr. Carmyle to drive her to the boarding house, and started to walk there, hoping that the crisp morning air would effect a cure.

She wondered now how she could ever have looked with approval on her rash act. She wondered what demon of interference and meddling had possessed her, to make her blunder into people’s lives, upsetting them. She wondered that she was allowed to go around loose. She was nothing more nor less than a menace to society. Here was an estimable young man, obviously the sort of young man who would always have to be assisted through life by his relatives, and she had deliberately egged him on to wreck his prospects. She blushed hotly as she remembered that mad wireless she had sent him from the boat.

Miserable Ginger! She pictured him, his little stock of money gone, wandering footsore about London, seeking in vain for work; forcing himself to call on Uncle Donald; being thrown down front steps by haughty footmen; sleeping on the Embankment; gazing into the dark waters of the Thames with the stare of hopelessness; climbing onto the parapet and . . .

“Ugh!” said Sally.

She had arrived at the door of the boarding house, and Mrs. Meecher was regarding her with welcoming eyes, little knowing that to all practical intents and purposes she had slain in his prime a red-headed young man of amiable manners and—when not ill-advised by meddling, muddling females—of excellent behavior.

Mrs. Meecher was friendly and garrulous. “Variety,” the journal which, next to the little woolly dog Toto, was the thing she loved best in the world, had informed her on the Friday morning that Mr. Foster’s play had got over big in Detroit and that Miss Doland had made every kind of a hit. It was not often that the old alumni of the boarding house forced their way after this fashion into the Hall of Fame, and, according to Mrs. Meecher, the establishment was ringing with the news. That blue ribbon round Toto’s neck was being worn in honor of the triumph. There was also, though you could not see it, a chicken dinner in Toto’s interior, by way of further celebration. And was it true that Mr. Fillmore had bought the piece? A great man, was Mrs. Meecher’s verdict. Mr. Faucitt had always said so.

“Oh, how is Mr. Faucitt?” Sally asked, reproaching herself for having allowed the pressure of other matters to drive all thoughts of her late patient from her mind.

“He’s gone,” said Mrs. Meecher with such relish that to Sally in her morbid condition the words had only one meaning. She turned white and clutched at the banisters.

“Gone!”

“To England,” added Mrs. Meecher.

Sally was vastly relieved.

“Oh, I thought you meant—”

“Oh, no, not that.” Mrs. Meecher sighed, for she had been a little disappointed in the old gentleman, who had started out as such a promising invalid, only to fall away into the dullness of robust health once more. “He’s well enough. I never seen anybody better. You’d think,” said Mrs. Meecher, bearing up with difficulty under her grievance—“you’d think this here now Spanish influenza was a sort of a tonic or somep’n, the way he looks now. Of course,” she added, trying to find justification for a respected lodger, “he’d had good news. His brother’s dead.”

“What!”

“Not, I don’t mean, that that was good news, far from it, though, come to think of it, all flesh is as grass and we all got to be prepared for somep’n of the sort breaking loose . . . but it seems this here now brother of his—I didn’t know he’d a brother, and I don’t suppose you knew he had a brother: men are secretive, ain’t they?—this brother of his has left him a parcel of money, and Mr. Faucitt he had to get on the Wednesday boat quick as he could and go right over to the other side to look after things. Wind up the estate, I believe they call it. Left in a awful hurry, he did. Sent his love to you and said he’d write. Funny him having a brother now, wasn’t it? Not,” said Mrs. Meecher, at heart a reasonable woman, “that folks don’t have brothers. I got two myself, one in Portland, Ore., and the other goodness knows where he is. But what I’m trying to say—”

Sally disengaged herself and went up to her rooms. For a brief while the excitement which comes of hearing good news about those of whom we are fond acted as a stimulant, and she felt almost cheerful. Dear old Mr. Faucitt! She was sorry for his brother, of course, though she had never had the pleasure of his acquaintance; but it was nice to think that her old friend’s remaining years would be years of affluence.

Presently, however, she found her thoughts wandering back into their melancholy groove. She threw herself wearily on the bed. She was tired after her bad night. But she could not sleep. Remorse kept her wakeful. Besides, she could hear Mrs. Meecher prowling disturbingly about the house, apparently in search of some one, her progress indicated by creaking boards and the strenuous yapping of Toto.

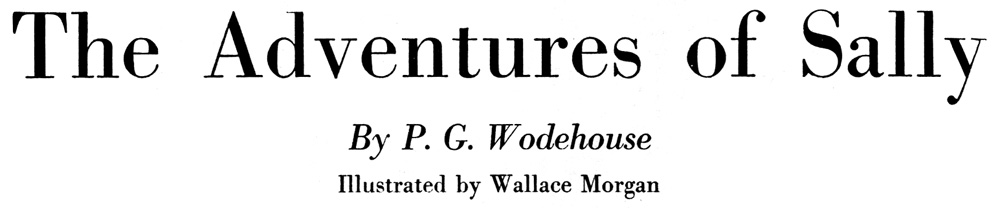

Sally turned restlessly and, having turned, remained for a long instant transfixed and rigid. She had seen something, and what she had seen was enough to surprise any girl in the privacy of her bedroom. From underneath the bed there peeped coyly forth an undeniably masculine shoe and six inches of gray trouser leg.

Sally bounded to the floor. She was a girl of courage, and she meant to probe this matter thoroughly.

“What are you doing under my bed?”

The question was a reasonable one, and evidently seemed to the intruder to deserve an answer. There was a muffled sneeze, and he began to crawl out.

The shoe came first. Then the legs. Then a sturdy body in a dusty coat. And finally there flashed on Sally’s fascinated gaze a head of so nearly the maximum redness that it could only belong to one person in the world.

“Ginger!”

Mr. Lancelot Kemp, on all fours, blinked up at her.

“Oh, hullo!” he said.

IX

IT was not till she saw him actually standing there before her with his hair rumpled and a large smut on the tip of his nose that Sally really understood how profoundly troubled she had been about this young man and how vivid had been that vision of him bobbing about on the waters of the Thames, a cold and unappreciated corpse. She was a girl of keen imagination, and she had allowed her imagination to riot unchecked. Astonishment, therefore, at the extraordinary fact of his being there was for the moment thrust aside by relief. Never before in her life had she experienced such an overwhelming rush of exhilaration. She flung herself into a chair and burst into a screech of laughter which even to her own ears sounded strange. It struck Ginger as hysterical.

“I say, you know,” said Ginger as the merriment showed no signs of abating. Ginger was concerned. Nasty shock for a girl, finding blighters under her bed. Enough to make her go in off the deep end.

Sally sat up, gurgling, and wiped her eyes.

“Oh, I am glad to see you!” she gasped.

“No, really?” said Ginger, gratified. “That’s fine!” It occurred to him that some sort of apology would be a graceful act. “I say, you know, awfully sorry. About barging in here, I mean. Never dreamed it was your room. Unoccupied, I thought.”

“Don’t mention it. I ought not to have disturbed you. You were having a nice sleep, of course. Do you always sleep on the floor?”

“It was like this—”

“Of course, if you’re wearing it for ornament, as a sort of beauty spot,” said Sally, “all right. But, in case you don’t know, you’ve a smut on your nose.”

“Oh, my aunt! Not really?”

“Now, would I deceive you on an important point like that?”

“Do you mind if I have a look in the glass?”

“Certainly, if you can stand it.”

GINGER moved hurriedly to the dressing table. “You’re perfectly right,” he announced, applying his handkerchief.

“I thought I was. I’m very quick at noticing things.”

“My hair’s a bit rumpled too, what?”

“Very much so, what?”

“You take my tip,” said Ginger earnestly, “and never lie about under beds. There’s nothing in it.”

“That reminds me. You won’t be offended if I ask you something?”

“No, no. Go ahead.”

“It’s rather an impertinent question. You may resent it.”

“No, no.”

“Well, then, what were you doing under my bed?”

“Oh, under your bed?”

“Yes. Under my bed. This. It’s a bed, you know. Mine. My bed. You were under it. Why? Or, putting it another way, why were you under my bed?”

“I was hiding.”

“Playing hide-and-seek? That explains it.”

“Mrs. What’s-her-name—Beecher—Meecher was after me.”

Sally shook her head disapprovingly. “You mustn’t encourage Mrs. Meecher in these childish pastimes. It unsettles her.”

Ginger passed an agitated hand over his forehead.

“It’s like this—”

“I hate to keep criticizing your appearance,” said Sally, “and personally I like it; but, when you clutched your brow just then, you put about a pound of dust on it. Your hands are probably grubby.”

Ginger inspected them. “They are!”

“Why not make a really good job of it and have a wash?”

“Do you mind?”

“I’d prefer it.”

“Thanks awfully. I mean to say it’s your basin, you know, and all that. What I mean is, I seem to be making myself pretty well at home.”

“Oh, no.”

“Touching the matter of soap—”

“Use mine. We Americans are famous for our hospitality.”

“Thanks awfully.”

“The towel is on your right.”

“Thanks awfully.”

“And I’ve a clothes brush in my bag.”

“Thanks awfully.”

Splashing followed, like a sea lion taking a dip.

“Now then,” said Sally, “why were you hiding from Mrs. Meecher?”

A careworn, almost hunted look came into Ginger’s face. “I say, you know, that woman is rather by way of being one of the lads, what! I mean to say, she’s got a nasty way with her. Scares me! Word was brought to me that she was on the prowl, so it seemed to me a judicious move to take cover till she sort of blew over. If she’d found me, she’d have made me take that dog of hers for a walk.”

“Toto?”

“Toto. You know,” said Ginger, with a strong sense of injury, “no dog’s got a right to be a dog like that. I don’t suppose there’s anyone keener on dogs than I am, but a thing like a woolly rat!” He shuddered slightly. “Well, one hates to be seen about with it in the public streets.”

“Why couldn’t you have refused in a firm but gentlemanly manner to take Toto out?”

“Ah! There you rather touch the spot. You see, the fact of the matter is, I’m a bit behind with the rent, and that makes it rather hard to take what you might call a firm stand.”

“But how can you be behind with the rent? I only left here the Saturday before last and you weren’t in the place then. You can’t have been here more than a week.”

“I’ve been here just a week. That’s the week I’m behind with.”

“But why? You were a millionaire when I left you at Roville.”

“Well, the fact of the matter is, I went back to the tables that night and lost a goodish bit of what I’d won. And, somehow or another, when I got to America, the stuff seemed to slip away.”

“What made you come to America at all?” said Sally, asking the question which, she felt, any sensible person would have asked at the opening of the conversation.

ONE of his familiar blushes raced over Ginger’s face. “Oh, I thought I would. Land of Opportunity, you know.”

“Have you managed to find any of the opportunities yet?”

“Well, I have got a job of sorts. I’m a waiter at a rummy little place on Second Avenue. The salary isn’t big, but I’d have wangled enough out of it to pay last week’s rent, only they docked me a goodish bit for breaking plates and what not. The fact is, I’m making rather a hash of it.”

“Oh, Ginger! You oughtn’t to be a waiter!”

“That’s what the boss seems to think.”

“I mean, you ought to be doing something ever so much better than that.”

“But what? You’ve no notion how well all these blighters here seem to be able to get along without my help. I’ve tramped all over the place, offering my services, but they all say they’ll try to carry on as they are.”

Sally reflected. “I know.”

“What?”

“I’ll make Fillmore give you a job. I wonder I didn’t think of it before.”

“Fillmore?”

“My brother. Yes, he’ll be able to use you.”

“What as?”

Sally considered. “As a—as a—oh, as his right-hand man.”

“ ’M, yes,” said Ginger reflectively. “Of course, I’ve never been a right-hand man, you know.”

“Oh, you’d pick it up. I’ll take you round to him now. He’s staying at the Astor.”

“There’s just one thing,” said Ginger.

“What’s that?”

“I might make a hash of it.”

“Heavens, Ginger! There must be something in this world that you wouldn’t make a hash of. Don’t stand arguing any longer. Are you dry? And clean? Very well, then. Let’s be off.”

“Right ho.”

GINGER took a step toward the door, then paused, rigid, with one leg in the air, as though some spell had been cast upon him. From the passage outside there had sounded a shrill yapping. Ginger looked at Sally. Then he looked—longingly—at the bed.

“Don’t be such a coward,” said Sally severely.

“Yes, but—”

“How much do you owe Mrs. Meecher?”

“Round about twelve dollars, I think it is.”

“I’ll pay her.”

Ginger flushed awkwardly. “No, I’m hanged if you will! I mean,” he stammered, “it’s frightfully good of you and all that, and I can’t tell you how grateful I am, but honestly I couldn’t—”

Sally did not press the point.

“Very well,” she said. “Have it your own way. Proud. That’s me all over, Mabel. Ginger!” she broke off sharply. “Pull yourself together. Where is your manly spirit? I’d be ashamed to be such a coward.”

“Awfully sorry, but, honestly, that woolly dog—”

“Never mind the dog. I’ll see you through.”

They came out into the passage almost on top of Toto, who was chasing phantom rats. Mrs. Meecher was maneuvering in the background. Her face lit up grimly at the sight of Ginger. “Mister Kemp! I been looking for you.”

Sally intervened brightly. “Oh, Mrs. Meecher,” she said, shepherding her young charge through the danger zone, “I was so surprised to meet Mr. Kemp here. He is a great friend of mine. We met in France. We’re going off now to have a long talk about old times, and then I’m taking him to see my brother.”

“Toto—”

“Dear little thing! You ought to take him for a walk,” said Sally. “It’s a lovely day. Mr. Kemp was saying just now that he would have liked to take him, but we’re rather in a hurry and shall probably have to get into a taxi.”

The front door had closed before Mrs. Meecher had collected her faculties; and Ginger, pausing on the sidewalk, drew a long breath.

“You know, you’re wonderful!” he said, regarding Sally with unconcealed admiration.

Sally accepted the compliment composedly. “Now we’ll go and hunt up Fillmore,” she said. “But there’s no need to hurry, of course, really. We’ll go for a walk first, and then call at the Astor and make him give us lunch. I want to hear all about you. I’ve heard something already. I met your cousin, Mr. Carmyle. He was on the train coming from Detroit. Did you know he was in America?”

“No. I’ve—er—rather lost touch with the Family.”

“So I gathered from Mr. Carmyle. And I feel hideously responsible. It was through me that all this has happened.”

“Oh, no.”

“Of course it was. I made you what you are to-day—I hope I’m satisfied. I know perfectly well that you wouldn’t have dreamed of savaging the Family as you seem to have done, if it hadn’t been for what I said to you at Roville. Ginger, tell me, what did happen? I’m dying to know. Mr. Carmyle said you insulted your uncle Ronald.”

“Donald. Yes, we did have a bit of a scrap, as a matter of fact. He made me go out to dinner with him and we—er—sort of disagreed. To start with, he wanted me to apologize to old Scrymgeour, and I rather gave it a miss.”

“Noble fellow!”

“Scrymgeour?”

“No, silly! You!”

“Oh, ah!” Ginger blushed. “And then there was all that about the soup, you know.”

“How do you mean ‘all that about the soup’? What about the soup? What soup?”

“Well, things sort of hotted up a bit when the soup arrived. I mean, the trouble seemed to start, as it were, when the waiter had finished ladling out the mulligatawny. Thick soup, you know.”

“I know mulligatawny is a thick soup. Yes?”

“Well, my old uncle—I’m not blaming him, don’t you know: more his misfortune than his fault; I can see that now—but he’s got a heavy mustache. Like a walrus, rather. And he’s a bit apt to inhale the stuff through it. And I—well, I asked him not to. It was just a suggestion, you know. We cut up fairly rough, and by the time the fish came round we were more or less down on the mat chewing holes in one another. My fault, probably. I wasn’t feeling particularly well-disposed toward the Family that night. I’d just had a talk with Bruce—my cousin, you know—in Piccadilly, and that had rather got the wind up me—Bruce always seems to get on my nerves a bit somehow. By the way, did you get the books?”

“What books?”

“Bruce said he wanted to send you some books. That was why I gave him your address.”

Sally stared. “He never sent me any books.”

SALLY walked on, a little thoughtfully. She was not a vain girl, but it was impossible not to perceive in the light of this fresh evidence that Mr. Carmyle had made a journey of three thousand miles with the sole object of renewing his acquaintance with her. It did not matter, of course, but it was vaguely disturbing.

“Go on telling me about your uncle,” she said.

“Well, there’s not much more to tell. I’d happened to get that wireless of yours just before I started out to dinner with him, and I was more or less feeling that I wasn’t going to stand any rot from the Family. One thing seemed to lead to another, and the show sort of busted up. He called me a good many things, and I got a bit fed, and finally I told him I hadn’t any more use for the Family and was going to start out on my own. And—well, I did, don’t you know. And here I am.”

Sally listened to this saga breathlessly. More than ever did she feel responsible for her young protégé. It was her plain duty to see that Ginger was started well in the race of life, and Fillmore was going to come in uncommonly handy.

“We’ll go to the Astor now,” she said, “and I’ll introduce you to Fillmore. He’s a theatrical manager, and he’s sure to have something for you.”

“It’s awfully good of you to bother about me.”

“Ginger,” said Sally, “I regard you as a grandson. Hail that cab, will you?”

X

IT seemed to Sally in the weeks that followed her reunion with Ginger Kemp that a sort of Golden Age had set in. On all the frontiers of her little kingdom there was peace and prosperity, and she woke each morning in a world so neatly smoothed and ironed out that the most captious pessimist could hardly have found anything in it to criticize.

True, Gerald was still a thousand miles away. Going to Chicago to superintend the opening of “The Primrose Way”—for Fillmore had acceded to his friend Ike’s suggestion of producing it first in Chicago—he had been called in by a distracted manager to revise the work of a brother dramatist whose comedy was in difficulties at one of the theatres in that city, and this meant that he would have to remain on the spot for some time to come. It was disappointing, but Sally refused to allow herself to be depressed. Life as a whole was much too satisfactory for that. Fillmore was going strong; Ginger was off her conscience; she had found an apartment; her new hat suited her, and “The Primrose Way” was a tremendous success. The production of the piece, according to Fillmore, had been the most terrific experience that had come to stir Chicago since the celebrated fire.

Of all these satisfactory happenings, the most satisfactory, to Sally’s thinking, was the fact that the problem of Ginger’s future had been solved. Ginger had entered the service of the Fillmore Nicholas Theatrical Enterprises, Ltd. (Managing Director, Fillmore Nicholas)—Fillmore would have made the title longer, only that was all that would go on the brass plate. What exactly he was, even Ginger hardly knew. Sometimes he felt like the man at the wheel; sometimes like a glorified office boy, and not so very glorified at that. For the most part he had to prevent the mob rushing in and getting at Fillmore, who sat in semiregal state in the inner office pondering great schemes.

BUT, though there might be an occasional passing uncertainty in Ginger’s mind as to just what he was supposed to be doing in exchange for the fifty dollars he drew every Friday, there was nothing uncertain about his gratitude to Sally for having pulled the strings and enabled him to do it. He tried to thank her every time they met, and nowadays they were meeting frequently, for Ginger was helping her to furnish her new apartment. In this task he spared no efforts. He said that it kept him in condition.

“And what I mean to say is,” said Ginger, pausing in the act of carrying a massive easy-chair to the third spot which Sally had selected in the last ten minutes, “if I didn’t sweat about a bit and help you after the way you got me that job—”

“Ginger, desist!” said Sally.

“Yes, but honestly—”

“If you don’t stop it, I’ll make you move that chair into the next room.”

“Shall I?” Ginger rubbed his blistered hands and took a new grip. “Anything you say.”

“Silly! Of course not. The only other rooms are my bedroom, the bathroom, and the kitchen. What on earth would I want a great lumbering chair in them for? All the same, I believe the first place we chose was the best.”

“Back she goes, then, what?”

Sally reflected frowningly. This business of setting up house was causing her much thought.

“No,” she decided. “By the window is better.” She looked at him remorsefully. “I am giving you a lot of trouble.”

“Trouble!” Ginger, accompanied by the chair, staggered across the room. “The way I look at it is this.” He wiped a bead of perspiration from his freckled forehead. “You got me that job, and—”

“Stop!”

“Right-ho. . . . Still, you did, you know.”

Sally sat down in the armchair and stretched herself. Watching Ginger work had given her a vicarious fatigue. She surveyed the room proudly. It was certainly beginning to look cozy. The pictures were up, the carpet down, the furniture very neatly in order. For almost the first time in her life she had the restful sensation of being at home. She had always longed during the past three years of boarding-house existence for a settled abode, a place where she could lock the door on herself and be alone. The apartment was small, but it was undeniably a haven. She looked about her and could see no flaw in it—except— She had a sudden sense of something missing.

“Hullo!” she said. “Where’s that photograph of me? I’m sure I put it on the mantelpiece yesterday.”

His exertions seemed to have brought the blood to Ginger’s face. He was a rich red. He inspected the mantelpiece narrowly. “No. No photograph here.”

“I know there isn’t. But it was there yesterday. Or was it? I know I meant to put it there. Perhaps I forgot. It’s the most beautiful thing you ever saw. Not a bit like me, but what of that? They touch ’em up in the dark room, you know. I value it because it looks the way I should like to look if I could.”

“I’ve never had a beautiful photograph taken of myself,” said Ginger, solemnly, with gentle regret.

“Cheer up!”

“Oh, I don’t mind. I only mentioned . . .”

“GINGER,” said Sally, “pardon my interrupting your remarks, which I know are valuable, but this chair is—not—right! It ought to be where it was at the beginning. Could you give your imitation of a pack mule just once more? And after that I’ll make you some tea. If there’s any tea—or milk—or cups.”

“There are cups all right. I know, because I smashed two the day before yesterday. I’ll nip round the corner for some milk, shall I?”

“Yes, please nip. All this hard work has taken it out of me terribly.”

Over the tea table Sally became inquisitive. “What I can’t understand about this job of yours, Ginger—which, as you are just about to observe, I was noble enough to secure for you—is the amount of leisure that seems to go with it. How is it that you are able to spend your valuable time—Fillmore’s valuable time, rather—juggling with my furniture every day?”

“Oh, I can usually get off.”

“But oughtn’t you to be at your post doing—whatever it is you do? What do you do?”

Ginger stirred his tea thoughtfully and gave his mind to the question.

“Well, I sort of mess about, you know.” He pondered. “I interview divers blighters and tell ’em your brother is out and take their names and addresses and—oh, all that sort of thing.”

“Does Fillmore consult you much?”

“He lets me read some of the plays that are sent in. Awful tosh, most of them. Sometimes he sends me off to a vaudeville house of an evening.”

“As a treat?”

“To see some special act, you know. To report on it. In case he might want to use it for this revue of his.”

“Which revue?”

“Didn’t you know he was going to put on a revue? Oh, rather. A whacking big affair. Going to cut out the Follies and all that sort of thing.”

“But—my goodness!” Sally was alarmed. It was just like Fillmore, she felt, to go branching out into these expensive schemes when he ought to be moving warily and trying to consolidate the small success he had had. An inexhaustible fount of optimism bubbled eternally within him.

“I shall have to talk to him,” said Sally decidedly. She was annoyed with Fillmore. Everything had been going so beautifully, with everybody peaceful and happy and prosperous and no anxiety anywhere, till he had spoiled things. Now she would have to start worrying again.

“Of course,” argued Ginger, “there’s money in revues. Over in London fellows make pots out of them.”

Sally shook her head. “It won’t do,” she said. “And I’ll tell you another thing that won’t do. This armchair. Of course it ought to be over by the window. You can see that yourself, can’t you?”

“Absolutely!” said Ginger, patiently preparing for action once more.

Editor’s note:

I made you what you are to-day—I hope I’m satisfied: Humorous inversion of lines from the song “The Curse of an Aching Heart” (1913) by Henry Fink and Al Piantadosi: “You made me what I am today / I hope you’re satisfied”

Printer’s error corrected above:

In Chapter IX, magazine had “How do you mean ‘all about the soup’?”; amended to “all that about the soup” as in all other versions.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums