Daily Mail, May 13, 1905

I AM the honorary secretary of the D. and S. of B.O.A.D., the P.K.M., the E.O.P.T.E.A.A.O.V.S., the I.O.T.R.O.T.C.E.F., and the P.O.D.I.S.

And I wish I wasn’t.

It was Babington who got me into it. Babington is a man

who is never really happy unless he’s lowering the record for absolute idiocy.

He came into the study one afternoon—we share a study—and said, “Look here, do

you see that some chaps at Swindon have formed a league which insists on kindness

to dumb animals, and about a hundred other things?”

It was Babington who got me into it. Babington is a man

who is never really happy unless he’s lowering the record for absolute idiocy.

He came into the study one afternoon—we share a study—and said, “Look here, do

you see that some chaps at Swindon have formed a league which insists on kindness

to dumb animals, and about a hundred other things?”

“Silly idiots,” I said.

“I don’t know,” said Babington. “It must be rather a rag. I vote we start one. I’ll be president, and you can be secretary.”

It’s no good talking to him when he’s taken like that. In the end it came to not one league, but five.

There was the Society for the Discouragement and Suppression of Bullying of all Descriptions, the Society for the Promotion of Kindness to Masters, the Encouragement of Politeness to Equals and Abolition of Vulgar Slang, the Society for Insisting on the Rights of the Citizen, Especially Fags and the Society for the Propagation of Decency in Smith’s. I suggested the last one.

Smith’s is the house next door, and there is always some sort of a row on between them and us. I thought mine the only decent league of the lot. And if it had come off, it would have been a great thing for the world. Smith’s wants improving badly.

I see that our mistake was in running such a lot of leagues all at once, specially as Babington and I were the only members. We were bound to muck it. We got off the mark first with the bullying business. Of course, there isn’t any bullying nowadays. Any one but Babington would have known that. But he said there was if you only looked for it, and he found a kid who’d just been touched up by Robinson, so he said he’d do for a start. Robinson’s the head of the house, and the kid had been bunking footer, so naturally he got touched up; but Babington said that wasn’t the point. The point was that a big chap had been detected striking a kid, and if that wasn’t bullying, what was?

So I had to write an official letter to Robinson: “Dear Sir,—It has come to the notice of the Society for the Discouragement and Suppression of Bullying of All Descriptions that you have been guilty of striking Blithers II. Should such a thing happen again, the society will be compelled to take steps.—I am, my dear sir, your obedient servant, the Hon. Sec.”

The rummy thing about the business was that Robinson thought Blithers had sent the letter, and touched him up again for cheek.

After that we wired in with the other leagues. The P.K.M. was the first to go wrong. You see, kindness is no good with masters. They’re so beastly suspicious they think you’re trying to rag them. That’s what happened when I tried to be kind to Grimstone. Perhaps I overdid it. Grimstone’s a Johnny who leaves the things on his desk all anyhow at the end of morning school, so I nipped in in the dinner hour, and put them all tidy. All the books in a neat heap, all the papers I thought he wouldn’t want again in the waste paper basket, and the mark-book and a pen and a clean piece of blotting-paper all ready. It looked top-hole. Yet he wasn’t pleased. “Who—who has had the impertinence to meddle with my desk?” he shouted. I rose and said, “Please sir, I tidied it up.” “You’re the most disorderly boy in the form. Two hundred lines.” Bit thick, considering the trouble I’d taken.

Then, during the afternoon there was more trouble. He kept dropping things—he always does, and I always dashed out from the other end of the room to pick them up, and—well, it had got to six hundred lines before four o’clock. Perhaps I ought to have seen that he wasn’t in the mood for it; but anyhow, when I went up to his desk at the end of school and asked him to tea in my study things got livelier than ever, and I’m in extra lesson for the next three half-holidays.

The E.O.P.T.E.A.A.O.V.S. was a bit of a frost too. I don’t know why it is that people have such suspicious minds. When I tried being Polite to my Equals, they thought I was being sarcastic, and I finished the evening on the floor with young Hackenschmidt III. sitting on my head.

The I.O.T.R.O.T.C.E.F. made trouble with the house-prefects. It began when I objected conscientiously to cleaning football boots. By the time I had finished passively resisting a request to make toast, I had begun to have enough of it. Babington, by the way, had kept out of it all. He said the hour was not yet ripe or something.

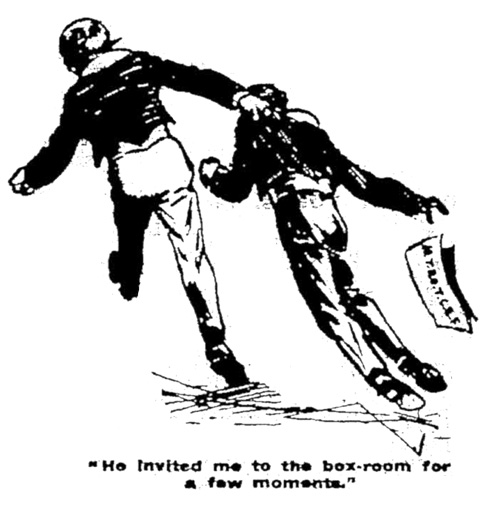

I was just bathing my eye after trying to propagate decency in Smith’s when Blithers came in. He said Robinson had found out who really wrote that letter, and I was to go to his study. Afterwards, added Blithers, who seemed annoyed, he himself would like to see me in the box-room for a few moments. After which, he said, he would help me to bed.

If there is a silver lining to this cloud—and there isn’t much of one—it is thought that when I am through with Robinson and Blithers, I shall have a word or two to say to Babington.

P. G. Wodehouse.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums