Maclean’s Magazine, December 1, 1921

GINGER took a step toward the door, then paused, rigid, with one leg in the air, as though some spell had been cast upon him. From the passage outside there had sounded a shrill yapping. Ginger looked at Sally. Then he looked longingly at the bed.

“Don’t be such a coward,” said Sally severely.

“Yes, but—”

“How much do you owe Mrs. Meecher?”

“Round about twelve dollars, I think, it is.”

“I’ll pay her.”

Ginger flushed awkwardly. “No, I’m hanged if you will! I mean,” he stammered, “it’s frightfully good of you and all that, and I can’t tell you how grateful I am, but honestly I couldn’t—”

Sally did not press the point. She liked him the better for a rugged independence which in the days of his impecuniousness brother Fillmore had never dreamed of exhibiting.

“Very well,” she said. “Have it your own way. Proud. That’s me all over, Mabel. Ginger!” she broke off sharply. “Pull yourself together. Where is your manly spirit? I’d be ashamed to be such a coward.”

“Awfully sorry, but, honestly, that woolly dog—”

“Never mind the dog. I’ll see you through.”

THEY passed on down the stairs and Ginger, pausing on the sidewalk drew a long breath.

“You know, you’re wonderful!” he said, regarding Sally with unconcealed admiration.

Sally accepted the compliment composedly. “Now we’ll go and hunt up Fillmore,” she said. “But there’s no need to hurry, of course, really. We’ll go for a walk first, and then call at the Astor and make him give us lunch. I want to hear all about you. I’ve heard something already. I met your cousin Mr. Carmyle. He was on the train coming from Detroit. Did you know he was in America?”

“No. I’ve—er—rather lost touch with the Family.”

“So I gathered from Mr. Carmyle. And I feel hideously responsible. It was all through me that all this has happened.”

“Oh, no.”

“Of course it was. Ginger tell me, what did happen? I’m dying to know. Mr. Carmyle said you insulted your uncle Ronald.”

“Donald. Yes, we did have a bit of a scrap, as a matter of fact. He made me go out to dinner with him and we—er—sort of disagreed. To start with, he wanted me to apologize to old Scrymgeour, and I rather gave it a miss.”

“Noble fellow!”

“Scrymgeour?”

“No, silly! You!”

“Oh, ah!” Ginger blushed. “And then there was all that about the soup, you know.”

“How do you mean ‘all that about the soup’? What about the soup? What soup?”

“Well, things sort of hotted up a bit when the soup arrived.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I mean, the trouble seemed to start as it were, when the waiter had finished ladling out the mulligatawny. Thick soup, you know.”

“I know mulligatawny is a thick soup. Yes?”

“Well, my old uncle—I’m not blaming him, don’t you know; more his misfortune than his fault; I can see that now—but he’s got a heavy mustache. Like a walrus, rather. And he’s a bit apt to inhale the stuff through it. And I—well, I asked him not to. It was just a suggestion, you know. We cut up fairly rough, and by the time the fish came round we were more or less down on the mat chewing holes in one another. My fault probably. I wasn’t feeling particularly well-disposed toward the family that night. I’d just had a talk with Bruce—my cousin, you know—in Piccadilly, and that had rather got the wind up me—Bruce always seems to get on my nerves a bit somehow—and Uncle Donald asking me to dinner and all that. . . . . .By the way, did you get the books?”

“What books?”

“Bruce said he wanted to send you some books. That was why I gave him your address.”

Sally stared. “He never sent me any books.”

“Well, he said he was going to, and I had to tell him where to send them.”

Sally walked on, a little thoughtfully. She was not a vain girl, but it was impossible not to perceive in the light of this fresh evidence that Mr. Carmyle had made a journey of three thousand miles with the sole object of renewing his acquaintance with her.

“Go on telling me about your uncle,” she said.

“Well, there’s not much more to tell. I’d happened to get that wireless of yours just before I started out to dinner with him, and I was more or less feeling that I wasn’t going to stand any rot from the family. I’d got to the fish course, hadn’t I? Well, we managed to get through that somehow, but we didn’t survive the fillet steak. One thing seemed to lead up to another, and the show sort of bust up. He called me a good many things, and I got a bit fed, and finally I told him I hadn’t any more use for the Family and was going to start out on my own. And—well, I did, don’t you know. And here I am.”

“We’ll go to the Astor now,” she said, “and I’ll introduce you to Fillmore. He’s a theatrical manager, and he’s sure to have something for you.”

“It’s awfully good of you to bother about me.”

“Ginger,” said Sally. “I regard you as a grandson. Hail that cab, will you?”

X

IT SEEMED to Sally in the weeks that followed her reunion with Ginger Kemp that a sort of Golden Age had set in. On all the frontiers of her little kingdom there was peace and prosperity, and she woke each morning in a world so neatly smoothed and ironed out that the most captious pessimist could hardly have found anything in it to criticize.

True, Gerald was still a thousand miles away. Going to Chicago to superintend the opening of “The Primrose Way”—for Fillmore had acceded to his friend Ike’s suggestion in the matter of producing it first in Chicago—he had been called in by a distracted manager to revise the work of a brother dramatist whose comedy was in difficulties at one of the theatres in that city and this meant that he would have to remain on the spot for some time to come. It was disappointing, for Sally had been looking forward to having him back in New York in a few days, but she refused to allow herself to be depressed. Life as a whole was much too satisfactory for that. Life, indeed, in every other respect seemed almost perfect. Fillmore was going strong; Ginger was off her conscience; she had found an apartment; her new hat suited her, and “The Primrose Way” was a tremendous success.

Of all these satisfactory happenings, the most satisfactory to Sally’s thinking was the fact that the problem of Ginger’s future had been solved. Ginger had entered the service of the Fillmore Nicholas Theatrical Enterprises, Ltd. (Managing Director, Fillmore Nicholas)—Fillmore would have made the title longer, only that was all that would go on the brass plate—and was to be found daily in the outer office, his duties consisting, it seemed mainly in reading the evening papers. What exactly he was, even Ginger hardly knew. Sometimes he felt like the man at the wheel; sometimes like a glorified office boy, and not so very glorified at that. For the most part he had to prevent the mob rushing in and getting at Fillmore, who sat in semi-regal state in the inner office pondering great schemes.

BUT, though there might be an occasional passing uncertainty in Ginger’s mind as to just what he was supposed to be doing in exchange for the fifty dollars he drew every Friday, there was nothing uncertain about his gratitude to Sally for having pulled the strings and enabled him to do it. He tried to thank her every time they met, and nowadays they were meeting frequently, for Ginger was helping her to furnish her new apartment. In this task he spared no efforts. He said that it kept him in condition.

“And what I mean to say is,” said Ginger, pausing in the act of carrying a massive easy-chair to the third spot which Sally had selected in the last ten minutes, “if I didn’t sweat about a bit and help you after the way you got me that job—”

“Ginger, desist!” said Sally.

“Yes, but honestly—”

“If you don’t stop it, I’ll make you move that chair into the next room.”

Sally sat down in the armchair and stretched herself. Watching Ginger work had given her a vicarious fatigue. The apartment was small, but it was undeniably a haven. She looked about her and could see no flaw in it—except—she had a sudden sense of something missing.

“Hullo!” she said. “Where’s that photograph of me? I’m sure I put it on the mantelpiece yesterday.”

His exertions seemed to have brought the blood to Ginger’s face. He was a rich red. He inspected the mantelpiece narrowly. “No. No photograph here.”

“I know there isn’t. But it was there yesterday. Or was it! I know I meant to put it there. Perhaps I forgot. It’s the most beautiful thing you ever saw. not a bit like me, but what of that? They touch ’em up in the dark room, you know. I value it because it looks the way I should like to look if I could.”

“I’ve never had a beautiful photograph taken of myself,” said Ginger, solemnly, with gentle regret.

“Cheer up!”

“Oh, I don’t mind. I only mentioned——”

“GINGER,” said Sally, “Pardon my interrupting your remarks, which I know are valuable, but this chair is—not—right. It ought to be where it was at the beginning. Could you give your imitation of a pack mule just once more? And after that I’ll make you some tea. If there’s any tea—or milk—or cups.”

“There are cups all right. I know because I smashed two the day before yesterday. I’ll nip round the corner for some milk, shall I?”

“Yes, please nip. All this hard work has taken it out of me, terribly.”

Over the tea table Sally became inquisitive. “What I can’t understand about this job of yours, Ginger—which, as you are just about to observe, I was noble enough to secure for you—is the amount of leisure that seems to go with it. How is it that you are able to spend your valuable time—Fillmore’s valuable time, rather—juggling with my furniture every day?”

“Oh, I can usually get off.”

“But oughtn’t you to be at your post doing—whatever it is you do? What do you do?”

Ginger sipped his tea thoughtfully and gave his mind to the question.

“Well, I sort of mess about, you know.” He pondered. “I interview divers blighters and tell ’em your brother is out and take their names and addresses and oh, all that sort of thing.”

“Does Fillmore consult you much?”

“He lets me read some of the plays that are sent in. Awful tosh, most of them. Sometimes he sends me off to a vaudeville house of an evening.”

“As a treat?”

“To see some special act, you know. To report on it. In case he might want to use it for this revue of his.”

“Which revue?”

“Didn’t you know he was going to put on a revue? Oh, rather. A whacking big affair. Going to cut out the Follies and all that sort of thing.”

“But—my goodness!” Sally was alarmed. It was just like Fillmore, she felt, to go branching out into these expensive schemes when he ought to be moving warily and trying to consolidate the small success he had had. All his life he had thought in millions where the prudent man would have been content with hundreds. An inexhaustible fount of optimism bubbled eternally within him. “That is rather ambitious,” she said.

“Yes. Ambitious sort of cove, your brother. Quite the Napoleon.”

“I shall have to talk to him,” said Sally decidedly. She was annoyed with Fillmore.

“Of course,” argued Ginger, “there’s money in revues. Over in London fellows make pots out of them.”

Sally shook her head. “It won’t do,” she said. “And I’ll tell you another thing that won’t do. That arm chair. Of course it ought to be over by the window. You can see that yourself, can’t you?”

“Absolutely!” said Ginger, patiently preparing for action once more.

SALLY’S anxiety with regard to her ebullient brother was not lessened by the receipt shortly afterward of a telegram from Miss Winch in Chicago.

“Have you been feeding Fillmore meat?” the telegram ran; and, while Sally could not have claimed that she completely understood it, there was a sinister suggestion about the message which decided her to wait no longer before making investigations. She tore herself away from the joys of furnishing and went round to the headquarters of the Fillmore Nicholas Theatrical Enterprises, Ltd. (Managing Director, Fillmore Nicholas), without delay.

Ginger, she discovered on arrival, was absent from his customary post, his place in the outer office being taken by a lad of tender years and pimply exterior, who thawed and cast off a proud reserve on hearing Sally’s name, and told her to walk right in. Sally walked right in and found Fillmore with his feet on an untidy desk, studying what appeared to be costume designs.

“Ah, Sally!” he said in the distrait, tired voice which speaks of vast preoccupations. Prosperity was still putting in its silent, deadly work on the Hope of the American Theatre. What, even at as late an epoch as the return from Detroit, had been merely a smooth fullness around the angle of the jaw was now frankly and without disguise a double chin. He was wearing a new waistcoat, and it was unbuttoned. “I am rather busy,” he went on. “Always glad to see you, but I am rather busy. I have a hundred things to attend to.”

“Well, attend to me. That’ll only make a hundred and one. Fill, what’s all this I hear about a revue?”

Fillmore looked as like a small boy caught in the act of stealing jam as it is possible for a great theatrical manager to look. He had been wondering in his darker moments what Sally would say about that project when she heard of it, and he had hoped that she would not hear of it until all the preparations were so complete that interference would be impossible. He was extremely fond of Sally, but there was, he knew, a lamentable vein of caution in her make-up which might lead her to criticize. And how can your man of affairs carry on if women are buzzing around criticizing all the time? He picked up a pen and put it down; buttoned his waistcoat and unbuttoned it, and scratched his ear with one of the costume designs.

“Oh, yes, the revue!”

“It’s no good saying ‘Oh, yes’! You know perfectly well it’s a crazy idea.”

“Really. . . .these business matters. . . .this interference—”

“I have no wish, Fill, to run your affairs for you, but that money of mine does make me a sort of partner, I suppose, and I think I have a right to raise a loud yell of agony when I see you risking it on a—”

“Pardon me,” said Fillmore loftily, looking happier. “Let me explain. Women never understand business matters. Your money is tied up exclusively in ‘The Primrose Way’, which, as you know, is a tremendous success. You have nothing whatever to worry about as regards any new production I may make.”

“I’m not worrying about the money. I’m worrying about you.”

A tolerant smiled played about the lower slopes of Fillmore’s face.

“Don’t be alarmed about me. I’m all right.”

“You aren’t all right. You’ve no business, when you’ve only just started as a manager, to be rushing into an enormous production like this. You can’t afford it.”

“My dear child, as I said before, women cannot understand these things. A man in my position can always command money for a new venture.”

“Do you mean to say you have found somebody silly enough to put up money?”

“Certainly. I don’t know that there is any secret about it. Your friend Mr. Carmyle has taken an interest in some of my forthcoming productions.”

“What!”

SALLY had been disturbed before, but she was aghast now. This was something she had never anticipated. Bruce Carmyle seemed to be creeping into her life like an advancing tide. There appeared to be no eluding him. Wherever she turned, there he was, and she could do nothing but rage impotently. The situation was becoming impossible.

Fillmore misinterpreted the note of dismay in her voice.

“It’s quite all right,” he assured her. “He’s a very rich man. Large private means besides his big income. Even if anything goes wrong—”

“It isn’t that. It’s—”

The hopelessness of explaining to Fillmore stopped Sally. And while she was chafing at this new complication which had come to upset the orderly course of her life there was an outburst of voices in the other office. Ginger’s understudy seemed to be endeavoring to convince somebody that the Big Chief was engaged and not to be intruded upon. In this he was unsuccessful for the door opened tempestuously and Miss Winch sailed in.

“Fillmore, you poor nut,” said Miss Winch, for, though she might wrap up her meaning somewhat obscurely in her telegraphic communications, when it came to the spoken word she was directness itself—“stop sticking straws in your hair and listen to me. You’re dippy!”

The last time Sally had seen Fillmore’s fiancée, she had been impressed by her imperturbable calm. Miss Winch in Detroit had seemed a girl whom nothing could ruffle. That she had lapsed now from this serene placidity struck Sally as ominous. Slightly though she knew her, she felt that it could be no ordinary happening that had so animated her sister-in-law-to-be.

“Ah! Here you are!” said Fillmore. He had started to his feet indignantly at the opening of the door, like a lion bearded in its den, but calm had returned when he saw who the intruder was.

“Yes, here I am!” Miss Winch dropped despairingly into a swivel chair and endeavored to restore herself with a stick of chewing gum. “Fillmore, darling, you’re the sweetest thing on earth and I love you, but on present form you could just walk straight into Bloomingdale’s and they’d give you the royal suite.”

“My dear girl—”

“What do you think?” demanded Miss Winch turning to Sally.

“I’ve just been telling him,” said Sally, welcoming this ally. “I think it’s absurd at this stage of things for him to put on an enormous revue. . . .”

“Revue?” Miss Winch stopped in the act of gnawing her gum. “What revue?” She flung up her arms. “I shall have to swallow this gum,” she said. “You can’t chew with your head going round. Are you putting on a revue too?”

FILLMORE was buttoning and unbuttoning his waistcoat. He had a hounded look. “Certainly, certainly,” he replied in a tone of some feverishness. “I wish you girls would leave me to manage—”

“Dippy!” said Miss Winch once more. “Telegraphic address, Teapot, Matteawan.” She swiveled round to Sally again. “Say, listen! This boy must be stopped. We must form a gang in his best interests and get him put away. What do you think he proposes doing? I’ll give you three guesses. Oh, what’s the use? You’d never hit it. This poor wandering lad has got it all fixed up to star me—me—in a new show!”

Fillmore removed a hand from his waistcoat buttons and waved it protestingly.

“I have used my own judgment—”

“Yes, sir!” proceeded Miss Winch, riding over the interruption. “That’s what he’s planning to spring on an unsuspicious public. I’m sitting peacefully in my room at the hotel in Chicago, pronging a few cents’ worth of scrambled eggs and reading the morning paper, when the telephone rings. Gentleman below would like to see me. Oh, ask him to wait. Business of flinging on a few clothes. Down stairs in elevator. Bright sunrise effects in lobby.”

“What on earth do you mean?”

“The gentleman had a head of red hair which had to be seen to be believed,” explained Miss Winch. “Lit up the lobby. Management had switched off all the electrics for sake of economy. An Englishman he was. Nice fellow. Named Kemp.”

“Oh, is Ginger in Chicago?” said Sally. “I wondered why he wasn’t on his little chair in the outer office.”

“I sent Kemp to Chicago,” said Fillmore, “to have a look at the show. It is my policy, if I am unable to pay periodical visits myself, to send a representative.”

“Save it for the long winter evenings,” advised Miss Winch cutting in on this statement of managerial tactics. “Mr. Kemp may have been there to look at the show, but his chief reason for coming was to tell me to beat it back to New York to enter into my kingdom. Fillmore wanted me on the spot, he told me, so that I could sit around in this office here, interviewing my supporting company. Me! Can you or can you not,” inquired Miss Winch frankly, “tie it?”

“Well—” Sally hesitated.

“Don’t say it! I know it just as well as you do. It’s all too sad for words.”

“You persist in underestimating your abilities, Gladys,” said Fillmore reproachfully. “I have had a certain amount of experience in theatrical matters. I have seen a good deal of acting—and I assure you that—”

MISS WINCH rose swiftly from her seat, kissed Fillmore energetically, and sat down again. She produced another stick of chewing gum, then shook her head and replaced it in her bag.

“You’re a darling old thing to talk that way,” she said, “and I hate to wake you out of your daydreams, but, honestly, Fillmore, dear, do just step out of the padded cell for one moment and listen to reason. I know exactly what has been passing in your poor disordered bean. You took Elsa Doland out of a minor part and made her a star overnight. She goes to Chicago, and the critics and everybody else rave about her. As a matter of fact,” she said to Sally with enthusiasm, for hers was an honest and a generous nature, “you can’t realize, not having seen her play there, what an amazing hit she has made. She really is a sensation. Everybody says she’s going to be the biggest thing on record. Very well, then. What does Fillmore do? The poor fish claps his hand to his forehead and cries: ‘Gadzooks! An idea! I’ve done it before, I’ll do it again. I’m the fellow who can make a star out of anything.’ Easy! Easy! And he picks on me!”

“My dear girl—”

“No, the flaw in the scheme is this. Elsa is a genius, and if he hadn’t made her a star somebody else would have done. But little Gladys? That’s something else again.” She turned to Sally. “You’ve seen me in action, and let me tell you you’ve seen me at my best. Give me a maid’s part, with a tray to carry on in Act One and a couple of ‘Yes, madam’s,’ in Act Two, and I’m there! Margaret Anglin hasn’t anything on me when it comes to saying ‘Yes, madam,’ and I’m willing to back myself for gold, notes, or lima beans against Sarah Bernhardt as a tray carrier. But there I finish. That lets me out. And anybody who thinks otherwise is going to lose a lot of money. Between ourselves, the only thing I can do really well is to cook—”

“My dear Gladys!” cried Fillmore, revolted.

“I’m a heaven-born cook, and I don’t mind notifying the world to that effect. I can cook a chicken casserole so that you would leave home and mother for it. Also, my English pork pies! One of these days I’ll take an afternoon off and assemble one for you. You’d be surprised! But acting—no. I can’t do it and I don’t want to do it. I only went on the stage for fun, and my idea of fun isn’t to plow through a star part with all the critics waving their axes in the front row, and me knowing all the time that it’s taking money out of Fillmore’s bank roll that ought to be going toward buying the little home with stationary washtubs. . . .Well, that’s that, Fillmore, old darling. I thought I’d just mention it.”

Sally could not help being sorry for Fillmore. He was sitting with his chin on his hands, staring moodily before him. Napoleon at Elba. It was plain that this project of taking Miss Winch by the scruff of the neck and hurling her to the heights had been very near his heart.

“If that is how you feel,” he said in a stricken voice, “there is nothing more to say.”

“Oh, yes, there is. We will now talk about this revue of yours. It’s off!”

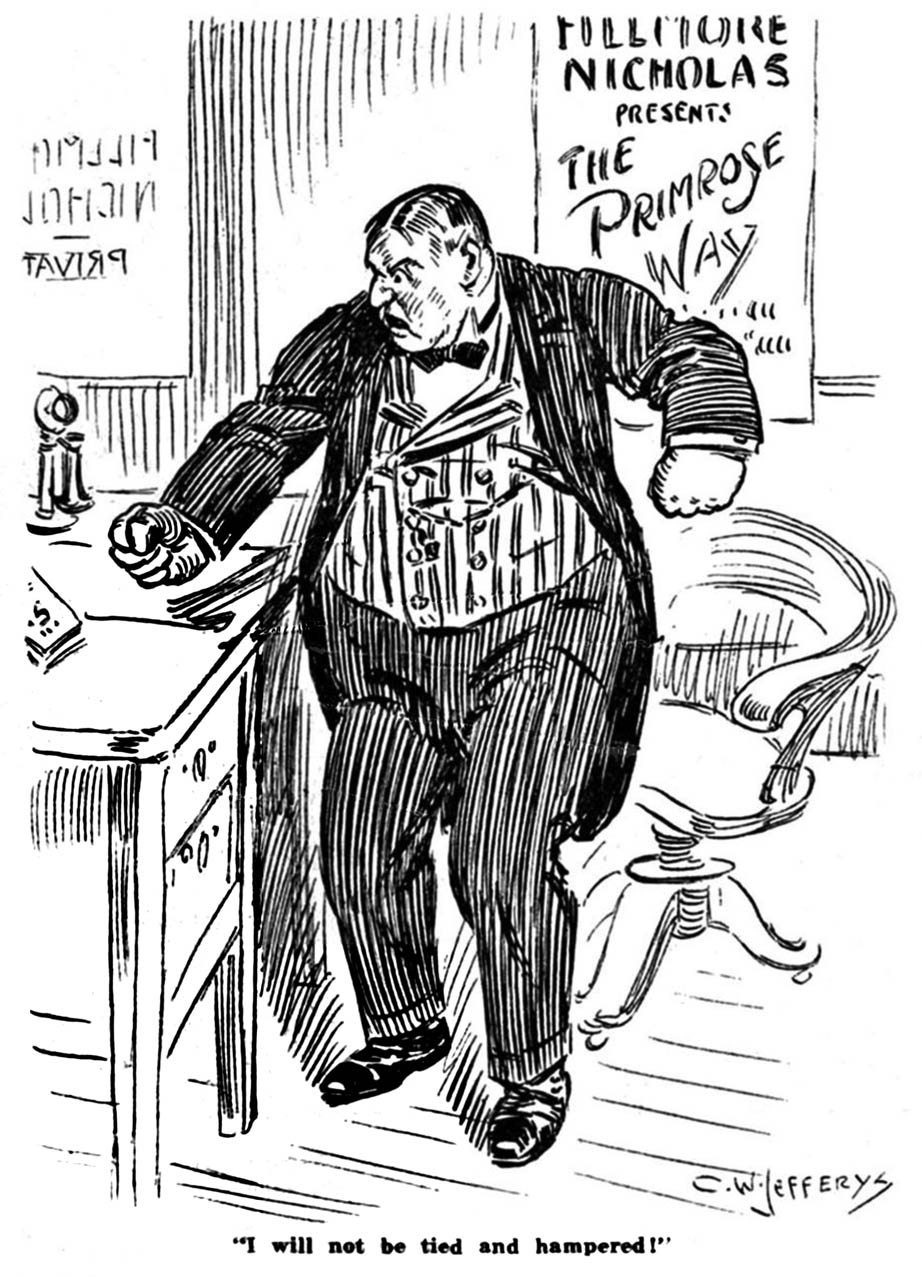

FILLMORE bounded to his feet. He thumped the desk with a well-nourished fist. A man can stand just so much.

“It is not off! Great heavens! It’s too much! I will not put up with this interference with my business concerns. I will not be tied and hampered. Here am I, a man of broad vision and. . . .and. . . .broad vision. . . .I form my plans. . . .my plans. . . .I form them. . . .I shape my schemes. . . .and what happens? A horde of girls flock into my private office while I am endeavoring to concentrate. . . .and concentrate. . . .I won’t stand it! Where’s my hat? I’ll tell you once and for all I won’t stand it. Advice, yes. Interference no. I. . . .I. . . .I—and kindly remember that!”

The door dosed with a bang. A fainter detonation announced the whirlwind passage through the outer office. Footsteps died away down the corridor.

Sally looked at Miss Winch, stunned. A roused and militant Fillmore was new to her.

Miss Winch took out the stick of chewing gum again and unwrapped it. “Isn’t he cute!” she said. “I hope he doesn’t get the soft kind,” she murmured, chewing reflectively.

“The soft kind?”

“He’ll be back soon with a box of candy,” explained Miss Winch, “and he will get that sloshy, creamy sort, though I keep telling him I like the other. Well, one thing’s certain. Fillmore’s got it up his nose! He’s beginning to hop about and sing in the sunlight. It’s going to be hard work to get that boy down to earth again.” Miss Winch heaved a gentle sigh. “I should like him to have enough left in the old stocking to pay the first year’s rent when the wedding bells ring out.” She bit meditatively on her chewing gum. “Not,” she said, “that it matters. I’d be just as happy in two rooms and a kitchenette, so long as Fillmore was there. You’ve no notion how dippy I am about him.” Her freckled face glowed. “He grows on me like a darned drug. And the funny thing is that I keep right on admiring him, though I can see all the while that he’s the most perfect chump. He is a chump, you know. That’s what I love about him. That and the way his ears wiggle when he gets excited. Chumps always make the best husbands. When you marry, Sally, grab a chump. Tap his forehead first, and if it rings solid don’t hesitate. All the unhappy marriages come from the husband having brains. What good are brains to a man? They only unsettle him.” She broke off and scrutinized Sally closely. “Say what do you do with your skin?”

She spoke with a solemn earnestness which made Sally laugh.

“What do I do with my skin? I just carry it around with me.”

“Well,” said Miss Winch enviously, “I wish I could train my darned fool of a complexion to get that way. Freckles are the devil. When I was eight, I had the finest collection in the Middle West and I’ve been adding to them right along. Some folks say lemon juice’ll cure ’em. Don’t you believe it! It just encourages ’em. Mine lap up all I give ’em and ask for more. There’s only one way of getting rid of freckles, and that is to saw the head off at the neck.”

“But why do you want to get rid of them?”

“Why? Because a sensitive girl, anxious to retain her future husband’s love, doesn’t enjoy going about looking like something out of a dime museum.”

“How absurd! Fillmore worships freckles.”

“Did he tell you so?” asked Miss Winch eagerly.

“Not in so many words, but you can see it in his eye.”

“Well, he certainly asked me to marry him, knowing all about them, I will say that. And, what’s more, I don’t think feminine loveliness means much to Fillmore, or he’d never have picked on me. Still, it is calculated to give a girl a jar, you must admit, when she picks up a magazine and reads an advertisement of a face cream beginning: ‘Your husband is growing cold to you. Can you blame him? Have you really tried to cure those unsightly blemishes?’—meaning what I’ve got. Still, I haven’t noticed Fillmore growing cold to me, so maybe it’s all right.” . . . . . .

IT WAS a subdued Sally who received Ginger when he called at her apartment a few days later on his return from Chicago. It seemed to her, thinking over the recent scene, that matters were even worse than she had feared. This absurd revue, which she had looked on as a mere isolated outbreak of foolishness, was, it would appear, only a specimen of the sort of thing her misguided brother proposed to do, a sample selected at random from a wholesale lot of frantic schemes. Fillmore, there was no longer any room for doubt, was preparing to express his great soul on a vast scale. Even if she could dissuade him from this particular rash act, it would only be a matter of minutes before he thought up something else equally devastating.

And she could not dissuade him; humiliating thought. She had grown so accustomed through the years to being the dominating mind that this revolt from her authority made her feel helpless and inadequate. Her self-confidence was shaken.

And Bruce Carmyle was financing him. . . . It was illogical, but Sally could not help feeling that when—she had not the optimism to say “if”—he lost his money, she would somehow be under an obligation to him, as if the disaster had been her fault. She disliked with a whole-hearted intensity the thought of being under an obligation to Mr. Carmyle.

Ginger said he had looked in to inspect the furniture, on the chance that Sally might want it shifted again, but Sally had no criticism to make on that subject. Weightier matters occupied her mind. She sat Ginger down in the armchair and started to pour out her troubles. It soothed her to talk to him. In a world which had somehow become chaotic again after an all too brief period of peace, he was solid and consoling.

“I shouldn’t worry,” observed Ginger with Winch-like calm, when she had finished drawing for him the picture of a Fillmore rampant against a background of expensive revues.

Sally nearly shook him. “It’s all very well to tell me not to worry,” she said. “How can I help worrying? Fillmore’s simply a baby, and he’s just playing the fool. He has lost his head completely. And I can’t stop him! That is the awful part of it. I used to be able to look him in the eye, and he would wag his tail and crawl back into his basket but now I seem to have no influence at all over him. He just snorts and goes on running round in circles, breathing fire.”

Ginger did not abandon his attempt to indicate the silver lining. “I think you’re making too much of all this, you know. I mean to say, it’s quite likely he’s found some mug—what I mean is, it’s just possible that your brother isn’t standing the racket himself. Perhaps some rich Johnny has breezed along with a pot of money. It often happens like that, you know. You read in the paper that some manager or other is putting on some show or other, when really the chap who’s actually supplying the pieces of eight is some anonymous lad in the background.”

“That is just what has happened, and it makes it worse than ever. Fillmore tells me that your cousin, Mr. Carmyle, is providing the money.”

THIS did interest Ginger. He sat up with a jerk. “Oh, I say!” he exclaimed.

“Yes,” said Sally, still agitated but pleased that she had at last shaken him out of his trying attitude of detachment.

Ginger was scowling. “That’s a bit off,” he observed.

“I think so too.”

“I don’t like that.”

“Nor do I.”

“Do you know what I think?” said Ginger, ever a man of plain speech and a reckless plunger into delicate subjects. “The blighter’s in love with you.”

Sally flushed. After examining the evidence before her, she had reached the same conclusion in the privacy of her thoughts, but it embarrassed her to hear the thing put into bald words.

“I know Bruce,” continued Ginger, “and, believe me, he isn’t the sort of cove to take any kind of a flutter without a jolly good motive. Of course he’s got tons of money. His old guv’nor was the Carmyle of Carmyle, Brent & Co.—coal mines up in Wales, and all that sort of thing—and I suppose he must have left Bruce something like half a million. No need for the fellow to have worked at all if he hadn’t wanted to. As far as having the stuff goes, he’s in a position to have all the shows he wants to. But the point is, it’s right out of his line. He doesn’t do that sort of thing. Not a drop of sporting blood in the chap! Why, I’ve known him sick the whole d—— Family onto me just because it got noised about that I’d dropped a couple of quid on the Grand National. If he’s really brought himself to the point of shelling out on a risky proposition like a show, it means something, take my word for it. And I don’t see what else it can mean except—Well, I mean to say, is it likely that he’s doing it simply to make your brother look on him as a good egg and a pal and all that sort of thing?”

“No, it’s not,” agreed Sally. “But don’t let’s talk about it any more. Tell me all about your trip to Chicago.”

“All right. But, returning to this binge for a moment, I don’t see how it matters to you one way or the other. You’re engaged to another Johnnie, and when Bruce rolls up and says ‘What about it?’ you’ve simply to tell him that the shot isn’t on the board and will he kindly melt away. Then you hand him his hat and out he goes.”

Sally gave a troubled laugh. “You think that’s simple, do you? I suppose you imagine that a girl enjoys that sort of interview? Oh, what’s the use of talking about it? It’s horrible, and no amount of arguing will make it anything else. Do let’s change the subject. How did you like Chicago?”

“Oh, all right. Rather a grubby sort of place.”

“So I’ve always heard. But you ought not to mind that, being a Londoner.”

“Oh, I didn’t mind it. As a matter of fact, I had rather a good time. Saw one or two shows, you know. Got in on my face as your brother’s representative, which was all to the good. By the way, it’s rummy how you run into people when you move about, isn’t it?”

“You talk as if you had been dashing about the streets with your eyes shut. Did you meet somebody you knew?”

“Chap I hadn’t seen for years. Was at school with him, as a matter of fact. Fellow named Foster. But I expect you know him too, don’t you? By name, at any rate. He wrote your brother’s show.”

SALLY’S heart jumped. “Oh! Did you meet Gerald—Foster?”

“Ran into him one night at the theatre.”

“And you were really at school with him?”

“Yes. He was in the footer team with me my last year.”

“Was he a scrum half too?” asked Sally dimpling.

Ginger looked shocked. “You don’t have two scrum halves in a team,” he said, pained at this ignorance on a vital matter. “The scrum half is the half who works the scrum and—”

“Yes, you told me that at Roville. What was Gerald—Mr. Foster, then? A six and seven-eighths, or something?”

“He was a wing three,” said Ginger with a gravity befitting his theme. “Rather fast, with a fairly decent swerve. But he would not learn to give the reverse pass inside to his center.”

“Ghastly!” said Sally.

“If,” said Ginger earnestly, “a wing’s bottled up by his wing and the back, the only thing he can do, if he doesn’t want to be bundled into touch, is to give the reverse pass.”

“I know,” said Sally. “If I’ve thought that once, I’ve thought it a hundred times. How nice it must have been for you, meeting again. I suppose you had all sorts of things to talk about?”

Ginger shook his head. “Not such a frightful lot. We were never very thick. You see, this chap Foster was by way of being a bit of a worm.”

“What!”

“A tick,” explained Ginger. “A rotter. He was pretty generally barred at school. Personally, I never had any use for him at all.”

Sally stiffened. She had liked Ginger up to that moment, and later on, no doubt, she would resume her liking for him, but in the immediate instant which followed these words she found herself regarding him with a stormy hostility. How dare he sit there saying things like that about Gerald?

Ginger who was lighting a cigarette without a care in the world, proceeded to develop his theme.

“It’s a rummy thing about school. Generally, if a fellow’s good at games—in the cricket team or the footer team and so forth—he can hardly help being fairly popular. But this blighter Foster—nobody seemed very keen on him. Of course he had a few of his own pals, but most of the chaps rather gave him a miss. It may have been because he was a bit sidey—had rather an edge on him, you know. Personally, the reason I barred him was because he wasn’t straight. You didn’t notice it if you weren’t thrown a goodish bit with him, of course, but he and I were in the same house and—”

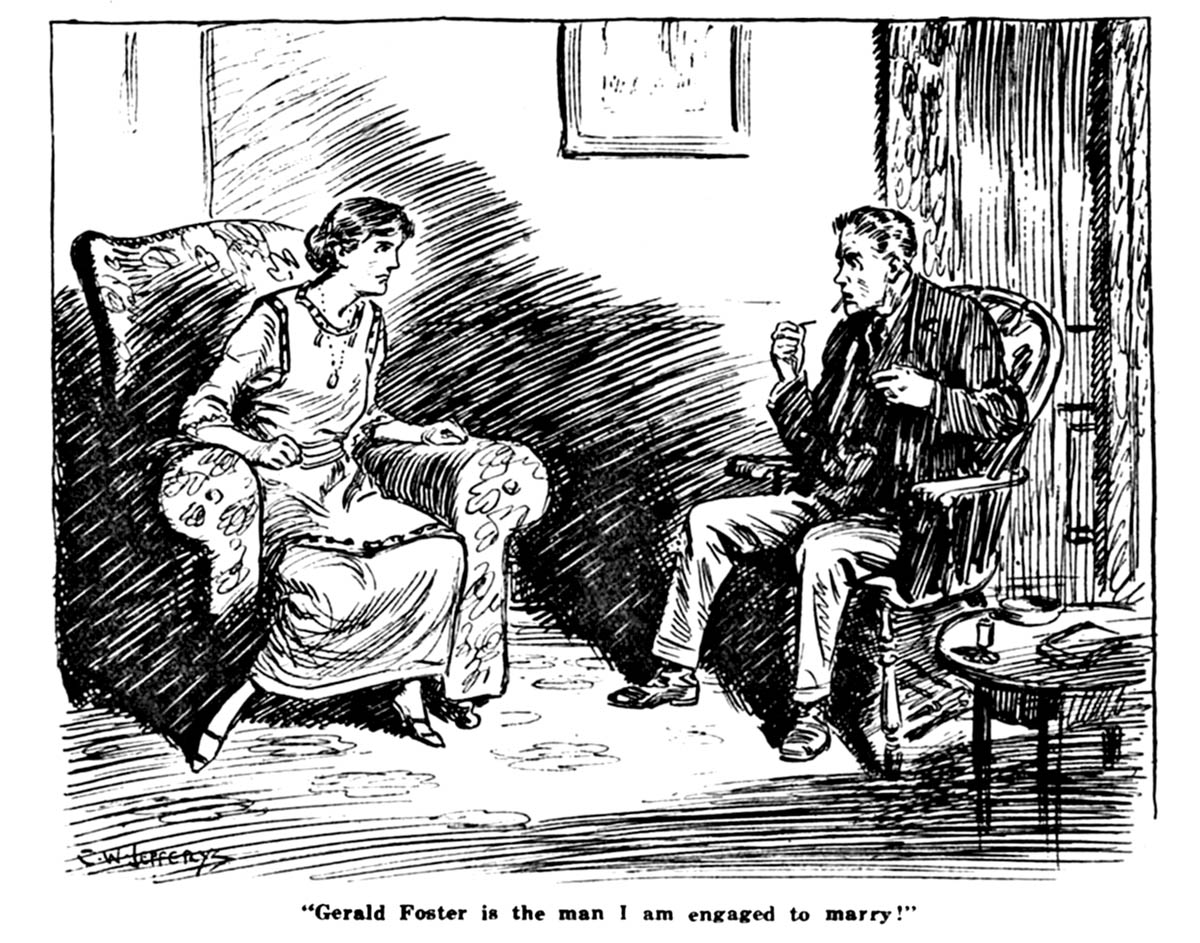

SALLY managed to control her voice though it shook a little. “I ought to tell you,” she said, and her tone would have warned him had he been less occupied, “that Mr. Foster is a great friend of mine.”

But Ginger was intent on the lighting of his cigarette, a delicate operation with the breeze blowing in through the open window. His head was bent, and he had formed his hands into a protective framework which half hid his face. “If you take my tip,” he mumbled, “you’ll drop him. He’s a wrong ’un.”

He spoke with the absent-minded drawl of preoccupation, and Sally could keep the conflagration under no longer. She was aflame from head to foot.

“It may interest you to know,” she said, shooting the words out like bullets from between clenched teeth, “that Gerald Foster is the man I am engaged to marry.”

Ginger’s head came slowly up from his cupped hands. Amazement was in his eyes, and a sort of horror. The cigarette hung limply from his mouth. He did not speak, but sat looking at her, dazed. Then the match burned his fingers, and he dropped it with a start. The sharp sting of it seemed to wake him. He blinked.

“You’re joking,” he said feebly. There was a note of wistfulness in his voice. “It isn’t true?”

Sally kicked the leg of her chair irritably. She read insolent disapproval into the words. He was daring to criticize!. . . . . .

“Of course it’s true!”

“But—” A look of hopeless misery came into Ginger’s pleasant face. He hesitated. Then, with the air of a man bracing himself to a dreadful but unavoidable ordeal, he went on. He spoke gruffly, and his eyes, which had been fixed on Sally’s wandered down to the match on the carpet. It was still glowing and mechanically he put a foot on it.

“Foster’s married,” he said shortly. “He was married the day before I left Chicago.”. . . . . .

IT SEEMED to Ginger that in the silence which followed, brooding over the room like a living presence, even the noises in the street had ceased, as though what he had said had been a spell, cutting Sally and himself off from the outer world. Only the little clock on the mantelpiece ticked—ticked—ticked, like a heart beating fast. He stared straight before him, conscious of a strange rigidity. He felt incapable of movement, as he had sometimes felt in nightmares, and not for all the wealth of America, could he have raised his eyes just then to Sally’s face. He could see her hand. It had tightened on the arm of her chair. The knuckles were white.

He was blaming himself bitterly now for his calfish clumsiness in blurting out the news so abruptly. And yet curiously, in his remorse there was something of elation. Never before had he felt so near to her. It was as though a barrier that had been between them had fallen.

Something moved. It was Sally’s hand slowly relaxing. The fingers loosed their grip, tightened again, then, as if reluctantly, relaxed once more. The blood flowed back.

“Your cigarette’s out.”

Ginger started violently. Her voice, coming suddenly out of the silence, had struck him like a blow. “Oh, thanks.”

He forced himself to light another match. It sputtered noisily in the stillness. He blew it out, and the uncanny quiet fell again.

Ginger drew at his cigarette mechanically. For an instant he had seen Sally’s face, white-cheeked and bright-eyed, the chin tilted like a flag flying over a stricken field. His mood changed. All his emotions had crystallized into a dull, futile rage, a helpless fury directed at a man a thousand miles away.

Sally spoke again. Her voice sounded small and far off, an odd flatness in it. “Married?”

Ginger threw his cigarette out of the window. He was shocked to find that he was smoking. Nothing could have been further from his intention than to smoke. He nodded.

“Whom has he married?”

Ginger coughed. Something was sticking in his throat, and speech was difficult. “A girl called Doland.”

“Oh, Elsa Doland?”

“Yes.”

“Elsa Doland.” Sally drummed with her fingers on the arm of her chair. “Oh, Elsa Doland?”

There was silence again. The little clock ticked fussily on the mantelpiece. Out in the street automobile horns were blowing. From somewhere in the distance came faintly the rumble of an elevated train. Familiar sounds, but they came to Sally now with a curious unreal sense of novelty. She felt as though she had been projected into another world where everything was new and strange and horrible—everything except Ginger. About him, in the mere sight of him, there was something known and heartening.

SUDDENLY she became aware that she was feeling that Ginger was behaving extremely well. She seemed to have been taken out of herself and to be regarding the scene from outside, regarding it coolly and critically; and it was plain to her that Ginger in this upheaval of all things, was bearing himself perfectly. He had attempted no banal words of sympathy. He had said nothing, and he was not looking at her. And Sally felt that sympathy just now would be torture and that she could not have borne to be looked at.

Ginger was wonderful. In that curious, detached spirit that had come upon her, she examined him impartially and gratitude welled up from the very depths of her. There he sat, saying nothing and doing nothing, as if he knew that all she needed, the only thing that could keep her sane in this world of nightmare, was the sight of that dear flaming head of his that made her feel that the world had not slipped away from her altogether.

Ginger did not move. The room had grown almost dark now. A spear of light from a street lamp shone in through the window.

Sally got up abruptly. Slowly, gradually, inch by inch, the great suffocating cloud which had been crushing her had lifted. She felt alive again. Her black hour had gone, and she was back in the world of living things once more. She was afire with a fierce, tearing pain that tormented her almost beyond endurance, but dimly she sensed the fact that she had passed through something that was worse than pain and, with Ginger’s stolid presence to aid her, had passed triumphantly.

“Go and have dinner, Ginger,” she said. “You must be starving.”

Ginger came to life like a courtier in the palace of the Sleeping Beauty. He shook himself and rose stiffly from his chair. “Oh—no,” he said. “Not a bit, really.”

Sally switched on the light and set him blinking. She could bear to be looked at now. “Go and dine,” she said. “Dine lavishly and luxuriously. You’ve certainly earned it.” Her voice faltered for a moment. She held out her hand. “Ginger,” she said shakily, “I—Ginger, you’re a pal.”

When he had gone Sally sat down and began to cry. Then she dried her eyes in a businesslike manner.

“There, Miss Nicholas,” she said, “you couldn’t have done that an hour ago. We will now boil you an egg for your dinner and see how that suits you!”

(To be Continued)

Notes:

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine had “all over, Mabel, Ginger!”; corrected to period after Mabel.

Magazine had period and “he” in “ ‘go and hunt up Fillmore,’ she said”

Magazine omitted “that” in “How do you mean ‘all that about the soup’?”

Magazine had “when the waited had finished”

Magazine had “brassplate”

Magazine omitted “I” in “What I can’t understand about this job”

Magazine had “one of the custume designs”

Magazine had “while, she was chaffing”

Magazine had “Sally had seen Fillmore’s fiancé”; amended to fiancée

Magazine had “policy. If I am unable”

Magazine had “was new to hear.”; changed to “her” as in books.

Magazine had “humilating”

Magazine had “accustomed through the year”; changed to “years” as in books.

Magazine had “he said pained at this ignorance”; comma added.

Magazine had “ ‘A thick,’ explained Ginger.”; changed to “tick” as in books.

Magazine had “struck him like a low”

Magazine omitted the comma after “white-cheeked and bright-eyed”

Magazine had an extraneous comma after “All his emotions”

Magazine failed to break for a new paragraph at “Whom has he married?”

Magazine had “A girl called Donald.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums