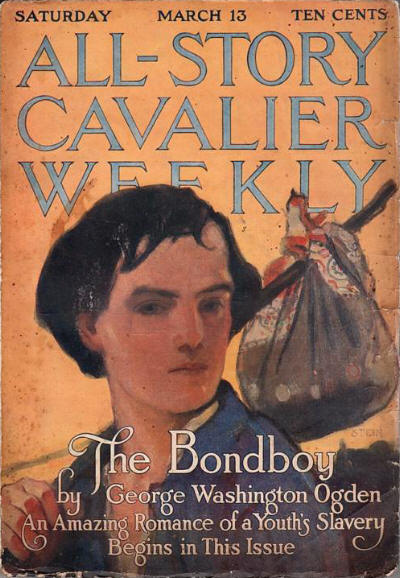

All-Story Cavalier Weekly, March 13, 1915

CHAPTER I.

A Strange Death.

HE room was the typical bedroom

of the typical better-class boarding-house, furnished, so far as it was furnished at all,

with a severe simplicity. It contained two beds, a pine chest of drawers, a

strip of faded carpet, and a wash-hand stand.

HE room was the typical bedroom

of the typical better-class boarding-house, furnished, so far as it was furnished at all,

with a severe simplicity. It contained two beds, a pine chest of drawers, a

strip of faded carpet, and a wash-hand stand.

All these things might have been guessed at from the other side of the closed door. But there was that on the floor which set this room apart from a thousand rooms of the same kind.

Flat on his back, one leg twisted oddly over the other, his hands clenched and his teeth gleaming through his black beard in a horrible grin, Captain John Gunner stared at the ceiling with eyes that saw nothing.

Until a moment before he had had the little room to himself. But now two people were standing just inside the door, looking down at him.

One was a large policeman, who twisted his cap nervously in his hands. The other was a tall, gaunt old woman in a rusty black dress, who gazed with pale eyes at the dead man.

Her face was quite expressionless.

The woman was Mrs. Pickett, owner of the Excelsior Boarding-house. The policeman’s name was Grogan. He was a genial giant, a terror to the riotous element of the Long Island water-front, but obviously ill at ease in the presence of death.

He drew in his breath with a curious hissing sound, wiped his forehead, and whispered: “Would you look at his eyes, ma’am!”

Mrs. Pickett did not answer. She had not spoken since she had brought the policeman into the room.

Officer Grogan looked at her quickly from the corner of his eyes. He was afraid of Mother Pickett, as was everybody else along the water-front.

Her silence, her pale eyes, and the quiet formidableness of her personality cowed even the tough old salts who patronized the Excelsior. She was a queen in that little community of sailormen.

“You’ve phoned for the doctor, ma’am?”

Mrs. Pickett nodded.

The breeze, blowing in through the open window, brought with it the sound of noisy laughter. A cheerful voice bellowed a popular song.

“That’s just how I found him,” said Mrs. Pickett. She did not speak loudly, but her voice made the policeman start.

He wiped his forehead again.

“It might have been apoplexy,” he hazarded.

Mrs. Pickett said nothing.

“Some guys drop in their tracks on account of a bum heart,” he went on. “There’s no marks on him.”

The old woman did not answer.

There was a sound of footsteps outside. A young man entered, carrying a black bag.

“Good morning, Mrs. Pickett. What’s the— Good Heavens!”

He dropped to his knees beside the body, and raised one of the arms. He lowered it gently to the floor and shook his head.

“Been dead for hours. When did you find him?”

“Twenty minutes back,” said the old woman. “I guess he died last night. He never would be called in the morning. Said he liked to sleep on. Well, he’s got his wish.”

“What did he die of, doc?” asked the policeman.

“Impossible to say without an examination. It looks like apoplexy, but it isn’t. It might be heart-disease, but I happen to know the poor fellow’s heart was as sound as a bell. He called in to see me only a week ago, and I tested him thoroughly. Lord knows what it is! The coroner’s inquest will tell us.”

He eyed the body almost resentfully.

“It beats me,” he said. “The man had no right to drop dead like this. He was a tough old sailor, who ought to have been good for another twenty years. If you ask me, though I can’t possibly be certain till after the inquest, I should say he had been poisoned.”

”For the love of Pete!” exclaimed Officer Grogan.

“How would he be poisoned?” said Mrs. Pickett.

“That’s more than I can tell you. There’s no glass about that he could have drunk it from. He might have got it in capsule form. But why should he have done it? He was always a pretty cheerful sort of old man, wasn’t he?”

“Sure!” said Officer Grogan. “He had the name of being a champion josher in these parts. I’ve had guys come to me all raw from being mixed up in arguments with him. He had a way with him. Kind of sarcastic, though he never tried it on me.”

“This man must have died quite early last night,” said the doctor. “What’s become of Captain Muller? If he shares this room he ought to be able to tell us something about it.”

“Captain Muller spent the night with some friends at Brooklyn,” said Mrs. Pickett. “He wasn’t here from after supper.”

The doctor looked round the room, frowning.

“I don’t like it. I can’t understand it. If this had happened in India I should have said the man had died from some form of snake-bite. I was out there two years, and I’ve seen a hundred cases of it. They all looked just like this. The thing’s ridiculous. How could a man be bitten by a snake in a water-front boarding-house? The whole thing’s mad. Was the door locked when you found him, Mrs. Pickett?”

Mrs. Pickett nodded.

“I opened it with my own key. I had been calling to him, and he didn’t answer, so I guessed something was wrong.”

The policeman spoke:

“You ain’t touched anything, ma’am? They’re always mighty particular about that. If doc’s right, and there’s been any funny work here, that’s the first thing they’ll ask.”

“Everything is just as I found it.”

“What’s that on the floor beside him?”

“That’s his harmonica. He liked to play it of an evening in his room. I’ve had complaints about it from some of the gentlemen; but I never saw any harm, so as he didn’t play too late.”

“Seems as if he was playing it when—it happened. That don’t look much like suicide, doc.”

“I didn’t say it was suicide.”

Officer Grogan whistled.

“You don’t think—”

“I don’t think anything—till after the inquest. All I say is that it’s queer.”

Another aspect of the matter seemed to strike the policeman.

“I guess this ain’t going to help the Excelsior any, ma’am,” he said sympathetically.

Mrs. Pickett shrugged her shoulders. Silence fell upon the room.

“I suppose I had better telephone to the coroner,” said the doctor.

He went out, and after a momentary pause the policeman followed him.

Officer Grogan was not greatly troubled with nerves, but he felt a decided desire to be somewhere where he could not see those staring eyes.

Mrs. Pickett remained where she was, looking down at the dead man. Her face was still expressionless, but inwardly she was in a ferment. This was the first time such a thing as this had happened at the Excelsior, and, as Officer Grogan had hinted, it was not likely to increase the attractiveness of the house in the eyes of possible boarders.

However well established the reputation of a house may be for comfort and the excellence of its cuisine, if it is a house of tragedy, people, for a time at any rate, will look askance at it.

It was not the possible pecuniary loss which was troubling Mrs. Pickett. As far as money was concerned, she could have retired from business years before and lived comfortably on her savings. She was richer than those who knew her supposed.

It was the blot on the escutcheon of the Excelsior—the stain on the Excelsior’s reputation—which was tormenting her.

The Excelsior was her life. Starting many years before, beyond the memory of the oldest boarder, she had built up this model establishment, the fame of which had been carried to every corner of the world.

In saloons and places where sailormen gathered together from Liverpool to Yokohama, from Cape Town to Marseilles, the reputation of Pickett’s was of pure gold. Men spoke of it as a place where you were well fed, cleanly housed, and where petty robbery was unknown.

Such was the chorus of praise from end to end of the world that it is not likely that much harm could come to Pickett’s from a single mysterious death; but Mother Pickett was not consoling herself with such reflections.

She was wounded sore. Pickett’s had had a clean slate; now it had not. That was the sum of her thoughts.

She looked at the dead man with pale, grim eyes. From down the passage came the doctor’s voice as he spoke on the telephone.

CHAPTER II.

Detective Oakes.

THE offices of the Paul J. Snyder Detective Agency had grown in the course of half a dozen years from a single room to a palatial suite full of polished wood, clicking typewriters, and other evidences of success. Where once Mr. Snyder had sat and waited for clients and attended to those clients on the rare occasions when they arrived in person, he now sat in his private office and directed a corps of assistants.

His cap was no longer in his hand, and his time at the disposal of any who would pay a modest fee. He was an autocrat who accepted or refused cases at his pleasure.

He had just accepted a case. It seemed to him a case that might be nothing at all or something exceedingly big; and on the latter possibility he had gambled.

The fee offered was, judged by his present standards of prosperity, small; but the bizarre facts, coupled with something in the personality of the client, had won him over; and he touched the bell and desired that Mr. Oakes should be sent in to him.

Elliott Oakes was a young man who amused and interested Mr. Snyder. He was so intensely confident. He had only recently joined the staff, but he made very little secret of his intention of electrifying and revolutionizing the methods of the agency.

Mr. Snyder himself, in common with most of his assistants, relied for results on hard work and plenty of common sense. He had never been a detective of the showy type. Results had justified his methods, but he was perfectly aware that young Mr. Oakes looked on him as a dull old man who had been miraculously favored by luck.

Mr. Snyder had selected Oakes for the case in hand principally because it was one where inexperience could do no harm, and where the brilliant guesswork which the latter called his inductive reasoning might achieve an unexpected success.

It was one of those bizarre cases which call for the dashing amateur rather than the dogged rule-of-thumb professional.

Mr. Snyder had, moreover, a kind of superstitious faith in the luck of the beginner.

Another motive actuated Mr. Snyder in his choice. He had a strong suspicion that the conduct of this case was going to have the beneficial result of lowering Oakes’s self-esteem.

If failure achieved this end, Mr. Snyder felt that failure, though it would not help the agency, would not be an unmixed ill.

The door opened and Oakes entered tensely. He did everything tensely, partly from a natural nervous energy, and partly as a pose. He was a lean young man, with dark eyes and a thin-lipped mouth, and looked as like a typical detective as Mr. Snyder looked like a comfortably prosperous stock-broker.

Mr. Snyder had never bothered himself about the externals of his profession. One could imagine Mr. Snyder in his moments of leisure watching a ball-game or bowling. Oakes gave the impression of having no moments of leisure.

“Sit down, Oakes,” said Mr. Snyder. “I’ve a job for you.”

Oakes sank into a chair like a crouching leopard and placed the tips of his fingers together. He nodded curtly. It was part of his pose to be keen and silent.

“I want you to go to this address”—he handed him an envelope—“and look around. Whether you will find out anything, or whether there’s anything to find out, is more than I can say. When the old lady was telling me the story I own I was carried away. She made it convincing. She thinks it was murder. I don’t know what to think.”

“The facts?” said Oakes briefly.

Mr. Snyder smiled quietly to himself.

“The address on that envelope is of a boarding-house on the water-front, down in Long Island. You know the sort of place—retired sea-captains and so on.

“All most respectable. Don’t run away with the idea that I’m sending you to some melodramatic hell’s-kitchen where the guests are drugged and shanghaied on the day of their arrival.

“As far as I can gather, this place is a sort of male Martha Washington. In all its history nothing more sensational has happened than a case of suspected cheating at pinochle. Well, a man has died there.”

“Murdered?”

“I don’t know. That’s for you to find out. The coroner left it open. I don’t see how it could have been murder. The door was locked; nobody could have got in.”

“The window?”

“The window was open. But the room is on the first floor. And, anyway, you may dismiss the window. I remember the old lady saying there was a bar across it, and that nobody could have squeezed through.”

Oakes’s eyes glistened. He was interested.

“What was the cause of death?”

Mr. Snyder coughed.

“Snake-bite,” he said.

Oakes’s careful calm deserted him. He uttered a cry of astonishment.

“What!”

“It’s the literal truth. The medical examination proved that the fellow had been killed by snake-poison. To be exact, the poison of a snake known as the krait. In this Long Island boarding-house, in a room with a locked door, this man was stung by a krait. It’s a small snake, found principally in India.

“To add a little mystification to the limpid simplicity of the affair, when the door was opened there was no sign of any snake.

“It couldn’t have got out through the door, because the door was locked. It couldn’t have got up the chimney, because there was no chimney. And it couldn’t have got out of the window, because the window was too high up, and snakes can’t jump. So there you have it.”

He looked at Oakes with a certain quiet satisfaction. It had come to his ears that Oakes had been heard to complain of the infantile simplicity, unworthy of a man of his attainments, of the last two cases to which he had been assigned, and had said that he hoped some day to be given a problem which would be beyond the reasoning powers of a child of six.

It seemed to Mr. Snyder that he had got what he wanted.

“I should like further details,” said Oakes a little breathlessly.

“You had better apply to Mrs. Pickett, who owns the boarding-house. It was she who put the case in my hands. She is convinced that it is murder. But, excluding the ghosts, I don’t see how any third party could have taken a hand in the thing at all. However, she wanted a man from this agency, and was prepared to pay for him, so I said I would send one. It’s not for me to turn business away.

“So, as I said, I want you to go and put up at Mrs. Pickett’s Excelsior Boarding-House and do your best to put things straight. I would suggest that you pose as a ship’s chandler or something of that sort. You will have to be something maritime or they’ll get on to you.

“And if your visit produces no other results, it will at least enable you to make the acquaintance of a very remarkable woman. I commend Mrs. Pickett to your notice. By the way, she says she will help you in your investigations.”

Oakes laughed shortly. The idea amused him.

“Don’t you scoff at amateur assistance, my boy,” said Mr. Snyder in the fatherly manner which had made a score of criminals refuse to believe him a detective until the moment when the handcuffs snapped on their wrists. “Detection isn’t an exact science. It’s a question of using common sense and having a great deal of special information. Mrs. Pickett probably knows a great deal which neither you or I know, and it’s just possible that she may have some trivial piece of knowledge which will prove the key to this mystery.”

Oakes laughed again.

“It is very kind of Mrs. Pickett, but I think I prefer to trust to my own powers of deduction.”

“Do just what you please, but recollect that a detective is only a man, not an encyclopedia. He doesn’t know everything, and it may be just some small thing which he does not know which turns out to be the missing letter in the combination.”

Oakes rose. His face was keen and purposeful.

“I had better be starting at once,” he said. “I will mail you reports from time to time.”

“I shall be interested to read them,” said Mr. Snyder genially. “I hope your visit to the Excelsior will be pleasant. If you run across a man with a broken nose, who used to rejoice in the name of Horse-Face Simmons, give him my best. I had the pleasure of sending him up the road some years ago for highway robbery, and I understand that he has settled in those parts. And cultivate Mrs. Pickett; she’s worth while.”

The door closed, and Mr. Snyder lighted a fresh cigar.

“Damned young fool,” he murmured, and turned his mind to other matters.

CHAPTER III.

Flat Up Against It.

A DAY later Mr. Snyder sat in his office reading a typewritten manuscript. It appeared to be of a humorous nature, for as he read chuckles escaped him. Finishing the last sheet, he threw back his head and laughed heartily.

The manuscript had not been intended by its author for a humorous effort. What Mr. Snyder had been reading was the first of Elliott Oakes’s reports from the Excelsior. It was as follows:

I am sorry to be unable to report any real progress. I have formed several theories, which I will put forward later, but up to the present I cannot say that I am hopeful.

Directly I arrived here I sought out Mrs. Pickett, explained who I was, and requested her to furnish me with any further information which might be of service to me.

She is a strange, silent woman, who impressed me as having very little intelligence. Your suggestion that I should avail myself of her assistance in unraveling this mystery seems more curious than ever now that I have seen her.

She is a hard-working woman, who certainly conducts this boarding-house with remarkable efficiency, but I should not credit her with brains. She never speaks except when spoken to, and even then is curt to the point of unintelligibility.

However, I managed to extract from her a good deal of information, which may or may not prove useful.

The whole affair seems to me at the moment of writing quite inexplicable. Assuming that this Captain Gunner was murdered, there appears to have been no motive for the crime whatsoever.

I have made careful inquiries about him, and find that he was a man of fifty-five; had spent nearly forty years of his life at sea, the last dozen in command of his own ship; was of a somewhat overbearing and tyrannous disposition, though with a fund of rough humor; had traveled all over the world; and had been an inmate of the Excelsior for about ten months.

He had a small annuity, and no other money at all, which disposes of money as the motive of the crime.

In my character of James Burton, a retired ship’s chandler, I have mixed with the other boarders, and have heard all they have to say about the affair.

I gather that the deceased was by no means popular. He appears to have had a bitter tongue, and was not sparing in its use, and I have not met one man who seems to regret his death.

On the other hand, I have heard nothing which would suggest that he had any active and violent enemy. He was simply the unpopular boarder—there is always one in every boarding-house—but nothing more.

I have seen a good deal of the man who shared his room. He, too, is a sea-captain, by name Muller. He is a big, silent German, and it is not easy to get him to talk on any subject.

As regards the death of Captain Gunner, he can tell me nothing. It seems that on the night of the tragedy he was away at Brooklyn with some friends. All I have got from him is some information as to Captain Gunner’s habits, which leads nowhere. The dead man seldom drank except at night, when he would take some whisky. His head was not strong, and a little of the spirit was enough to make him semiintoxicated, when he would be hilarious and often insulting.

I gather that Muller found him a difficult roommate, but he is one of those placid Germans who can put up with anything. He and Gunner were in the habit of playing checkers together every night in their room, and Gunner had a harmonica which he played frequently.

Apparently, he was playing it very soon before he died, which is significant, as seeming to dispose of the idea of suicide.

But if Captain Gunner did not kill himself, I cannot at present imagine who did kill him, or why he was killed, or how.

As I say, I have one or two theories, but they are in a very nebulous state. The most plausible is that on one of his visits to India—I have ascertained that he made several voyages there—Captain Gunner may in some way have fallen foul of the natives.

Kipling’s story “The Mark of the Beast,” is suggestive. Is it not possible that Captain Gunner, a rough, overbearing man, easily intoxicated, may in a drunken frolic have offered some insult to an Indian god?

The fact that he certainly died of the poison of the krait, an Indian snake, supports this theory.

I am making inquiries as to the movements of several Indian sailors who were here in their ships at the time of the tragedy.

I have another theory. Does Mrs. Pickett know more about this affair than she appears to?

I may be wrong in my estimate of her mental qualities. Her apparent stupidity may be cunning.

But here again the absence of motive brings me up against a dead wall. I must confess that at present I do not see my way clearly. However, I will write again shortly.

Mr. Snyder derived the utmost enjoyment from the report. He liked the matter of it, and he liked Oakes’s literary style.

Above all, he was tickled by the obvious querulousness of it. Oakes was baffled, and his knowledge of Oakes told him that the sensation of being baffled was gall and wormwood to that high-spirited young gentleman.

Whatever might be the result of this investigation, it would at least have the effect of showing Oakes that there was more in the art of detection than he had supposed. It would teach him the virtue of patience.

He wrote his assistant a short note:

Dear Oakes:

Your report received. You certainly seem to have got the hard case which, I hear, you were pining for. I wish you luck.

Don’t build too much on plausible motives in a case of this sort. Fauntleroy, the London murderer, killed a woman for no other reason than that she had thick ankles. Many years ago I myself was on a case where a man murdered an intimate friend because of a dispute about a ball-game.

My experience is that five murderers out of ten act on the whim of the moment, without anything which, properly speaking, you could call a motive at all.

Yours,

Paul Snyder.

P.S.—I don’t think much of your Pickett theory. However, it’s up to you. Enjoy yourself.

CHAPTER IV.

Baffling Clues.

YOUNG Mr. Oakes, however, did not enjoy himself.

For the first time in his life he was beginning to be conscious of the possession of nerves. He had gone into this investigation with the self-confident alertness which characterized all his actions. He believed in himself thoroughly.

The fact that the case had the appearance of presenting unusual difficulties had merely stimulated him. He was tired of being assigned to investigations which offered no scope for the inductive genius which he considered that he possessed.

Hitherto he had been a razor cutting wood. Now, however, he told himself, he could really show Mr. Snyder the difference between modern methods and the stupid rule-of-thumb which seemed to be the agency’s only form of mental expression.

This mood had lasted for some hours. Then doubts had begun to creep in. The problem began to appear insoluble.

True, he had only just taken it up, but something told him that, for all the progress he was likely to make, he might just as well have been working on it for a month. He was baffled.

And every moment which he spent in the Excelsior Boarding House made it clearer to him that that infernal old woman with the pale eyes thought him an incompetent fool.

It was this, more than anything, which had brought to Elliott Oakes’s notice the fact that he had nerves. Those nerves were being sorely troubled by the quiet scorn of Mrs. Pickett’s gaze.

He began to think that perhaps he had been a shade too self-confident and brusk in the short interview which he had had with her on his arrival.

She had struck him as a thoroughly stupid old woman, and his manner had shown it.

He had been keen and abrupt during that interview. He had cut in on her remarks. He had examined her with regard to the facts which he needed to supplement those which he had had from Mr. Snyder with a curt superciliousness which now he was beginning to regret.

Such an attitude as he had assumed could only be justified by results, and the fear was creeping over him that he could not produce those results. Failure was staring him in the face. Since his arrival he had not ceased to brood over this problem, but he could see no light.

Mrs. Pickett’s pale eyes somehow made him feel very young.

Elliott Oakes’s first act after his brief interview with the proprietress had been to examine the room where the tragedy had taken place. The body had gone, but, with that exception, nothing had been moved.

Oakes belonged to the magnifying-glass school of detection. The first thing he did on entering the room was to make a careful examination of the floor, the walls, the furniture, and the window-sill.

He would have hotly denied the assertion that he did this because it looked well, but he would have been hard put to it to advance any other reason.

He discovered what probably, in his heart, he had expected to discover—nothing. There were particles of dust on the floor, but they conveyed nothing to him. There were marks on the window-sill, but what they signified he had no notion.

However, he went through his performance conscientiously. It was his way of taking formal possession of the case.

He rose, a little flushed, and, abandoning the magnifying-glass, made a comprehensive survey of the room from a position near the door. If he discovered anything, his discoveries were entirely negative, and served only to deepen the mystery of the case.

As Mr. Snyder had said, there was no chimney, and nobody could have entered through the locked door.

There remained the window. It was small, and apprehensiveness possibly on the score of burglars had caused the proprietress to make it doubly secure with an iron bar. No human being could have squeezed his way through it.

After a quarter of an hour he left the room, locking the door behind him. No more unsatisfactory preliminary investigation could ever have been made.

It was late that night that he wrote and despatched to headquarters the report which had amused Mr. Snyder. The interval he filled up by making guarded inquiries among his fellow boarders.

He had no difficulty in making them talk. Nothing like the death of Captain Gunner had ever happened among them, and the difficulty would have been to start successfully any other topic of conversation.

Captain Muller, the big German, who, by virtue of being the dead man’s roommate, might, if he had desired, have held the position of principal speaker and star-witness, was the only man who seemed to have nothing to say. He was plainly a man of silent habit, and not even his vicarious connection with the tragedy could shake him from it.

The theories of the others ranged from heart-disease—in spite of the doctor’s definite statement to the contrary—to the ingenious suggestion from one of the party that Captain Gunner had been bitten by a snake at some previous date, several years before, and that the poison had lain dormant in his system until this moment.

The theorist claimed to have known a man who had made a voyage with a man to whom a precisely similar experience had happened. The only weak spot in the story was the fact that the speaker’s informant had the reputation of being the most persevering liar in his native State of Massachusetts, and had twice claimed to have see the sea-serpent.

Young Mr. Oakes went to his room with the beginnings of a bad headache.

All the really reliable information which he had acquired from his companions he had embodied in his report, and, as he had admitted in that document, it did not lead to anything very definite.

It was in his room that he first snatched at the avenging Indian theory as a possible solution, and, if he had been honest with himself he would have admitted that there was a good deal of the emotions of the drowning man toward the straw in his attitude toward it.

Nothing supported the theory except his active imagination.

Captain Gunner had certainly visited India in the course of his wanderings, but there the trail stopped. He had never shown any of the signs which might be supposed to mark the man conscious of being ceaselessly pursued by the outraged servants of an Indian god.

In his rambles along the water-front he had frequently met Indians, but he had betrayed no nervousness. On the contrary, if they happened to get in his way, he had usually kicked them. This was not the attitude of a haunted man.

Oakes was bound to admit that his confidence in the Indian theory was not very robust. He had put it to Mr. Snyder in his report more as an evidence of good faith, as a proof that his busy brain was at work and that he was bringing a laudable nimbleness of imagination to the quest, than because he really believed it.

His innuendo against Mrs. Pickett was pure spite. The woman irritated him profoundly, and it soothed him to fancy himself even for a moment watching her like a hawk, and causing her uneasiness by his relentless pursuit.

He was a detective, but he was human.

Certainly Elliott Oakes was not enjoying himself. The man of all others whom he had admired and revered most intensely all his life—Elliott Oakes, to wit—was beginning to show signs of not being so tremendous as he had always pictured him.

He was being tried and found wanting.

He wished Mrs. Pickett would not look at him like that. It hurt his self-esteem.

CHAPTER V.

The Mystery Solved?

TWO days later Mr. Snyder sat in his office. There was a telegram before him.

It ran as follows:

Have solved Gunner mystery. Returning.

Oakes.

Mr. Snyder rang the bell.

“Send Mr. Oakes to me directly he arrives,” he said.

He put his feet up on the desk, tilted his chair back, and frowned at the ceiling.

He was pained to find that the chief emotion with which the telegram from Oakes had affected him was annoyance. The swift solution of such an apparently insoluble problem would reflect the highest credit on the agency, and there were picturesque circumstances connected with the case which would make it popular with the newspapermen and lead to its being accorded a great deal of publicity.

On the whole, no case of recent years promised to give the agency a bigger advertisement than this one.

Yet, in spite of all this, Mr. Snyder was annoyed. It was ridiculous and unprofessional of him to be annoyed, but human nature was too strong for him.

He realized now how large a part the desire to reduce Oakes’s self-esteem had played with him.

Looking at the thing honestly, he owned to himself that he had had no expectation that the young man would come within a mile of a reasonable solution of the mystery; and he had calculated that his failure would prove a valuable piece of education for him.

For the professional was mixed up with the unprofessional in Mr. Snyder’s attitude toward his assistant. It was not only as a private individual that he had hoped to see Oakes reduced to humility by failure: he also believed that failure in this particular point in his career would make Oakes a more valuable asset to the agency.

Oakes had intelligence. That he had never denied. Mr. Snyder’s grievance against him was that he had only about half the intelligence with which he credited himself.

His aggressive belief in himself impaired his utility as a detective. He needed breaking in, and Mr. Snyder had looked to this case to effect this end.

And here he was, within a ridiculously short space of time, returning to the fold, not humble and defeated, but with flying colors.

Mr. Snyder looked forward with apprehension to the young man’s probable demeanor under the intoxicating influence of victory.

His apprehensions were well grounded. He had barely finished the second of the series of cigars which, like milestones, marked the progress of his afternoon, when the door opened and young Mr. Oakes entered, rampant.

Mr. Snyder could not repress a faint moan at the sight of him. One glance was enough to tell him that his worst fears were realized.

Few people in the history of New York can have been so pleased with themselves as Oakes obviously was at that moment. He diffused self-satisfaction like a scent. In some mysterious way he seemed to have grown bigger.

He was still tense, but his tenseness now was that of the leopard returning from some important kill, announcing his magnificence to the rest of the jungle.

He sat down before Mr. Snyder had time to invite him, and the older man looked with dismay at this significant sign of his increased importance.

“I got your telegram,” said Mr. Snyder.

Oakes nodded.

“It surprised you, eh?”

Mr. Snyder resented the patronizing tone of the question, but he had resigned himself to be patronized and gave no sign of resentment.

One of the old man’s chief virtues, which had compensated him for a certain lack of genius in his make-up, was his level-headedness and his ability to refuse anything to disturb him seriously. His sense of humor had saved him in a hundred difficult situations, and it saved him now.

He realized that Oakes could no more help being patronizing at this moment than a dog could help barking after retrieving its master’s walking-stick from a pond.

“Yes,” he replied. “I must say it did surprise me. I didn’t gather from your report that you had even found a clue. Was it the Indian theory that won out, or did you catch Mrs. Pickett with the goods?”

Oakes laughed tolerantly.

“Oh, that was all moonshine. I never really believed that truck. I put it in to fill up. I hadn’t begun to think about the case then—not really think.”

“No?”

“No. I was just looking around it—giving it the once over.”

“And having given it the once over—”

“Why, I took my coat off and waded in.”

“You weren’t long about it.”

“Not so very.”

Mr. Snyder extended his cigar-case.

“Light up and tell me all about it.”

“Well, I won’t say I haven’t earned this,” said Oakes, puffing smoke. “Shall I begin at the beginning?”

“Sure. But tell me first, who was it did it? Was it one of the boarders?”

“No.”

“Somebody from outside, then?”

Oakes smiled quietly.

“Yes, you might call it somebody from outside. But I had better trace my reasoning from the start.”

“That’s right. It spoils a story knowing the finish. Go to it.”

Oakes let the ash of his cigar fall delicately to the floor, another action which seemed significant to his employer. As a rule, his assistants, unless particularly pleased with themselves, used the ash-tray.

“My first act on arriving,” he said, “was to have a talk with Mrs. Pickett. A very dull old woman.”

“Curious. She struck me as rather intelligent.”

“Not on your life. She doesn’t know beans from buttermilk. She gave me no assistance whatever.

“I then examined the room where the death had taken place. It was much as you had described it. Locked door. Window high up. No chimney. I’m bound to say that, at first sight, it looked fairly unpromising.

“Then I had a chat with some of the other boarders. They had nothing to tell me that was of the least use. Most of them simply gibbered.

“I then gave up trying to get help from outside, and resolved to rely on my own intelligence.”

He smiled complacently.

“It is a theory of mine, Mr. Snyder, which I have found valuable that, in nine cases out of ten, remarkable things don’t happen.”

“I don’t quite get that.”

“I mean exactly what I say. I will put it another way if you like. What I mean is that the simplest explanation is nearly always the right one.”

“Well, I don’t—”

“I have tested and proved it. Consider this case. Was there ever a case which was more entitled by rights to a bizarre solution? One was almost inclined to believe in the supernatural. It seemed impossible that there should have been any reasonable explanation of the man’s death. Most men would have worn themselves out guessing at wild theories. If I had started to do that, I should have been guessing now.

“As it is—here I am. I trusted to my belief that nothing remarkable ever happens, and I won out.”

Mr. Snyder sighed softly. Oakes was entitled to a certain amount of gloating, but there was no doubt that his way of telling a story was a little trying.

“I believe in the logical sequence of events. I refuse to accept effects unless they are preceded by causes. In other words, with all due deference to you, Mr. Snyder, I simply decline to believe in a murder unless there is a motive for it.

“The first thing I set myself to ascertain was—what was the motive for this murder of Captain Gunner? And, after thinking it over and making every possible inquiry, I decided that there was no motive. Therefore, there was no murder. It was like an elementary sum.”

Mr. Snyder’s mouth opened, and he apparently intended to speak, but he changed his mind and Oakes proceeded:

“I then tested the suicide theory. What motive was there for suicide? There was no motive. Therefore, there was no suicide.”

This time Mr. Snyder spoke.

“Say, my boy, you haven’t been spending the last few days in the wrong house by any chance, have you? You will be telling me next that there wasn’t any dead man.”

Oakes smiled.

“Not at all. Captain John Gunner was dead as mutton, and, as the medical evidence proved, he died of the bite of a krait.”

Mr. Snyder shrugged his shoulders.

“Go on,” he said. “It’s your story. I’m listening.”

“Well, I won’t keep you long. Captain Gunner died from snake-bite for the very excellent reason that he was bitten by a snake.”

“Bitten by a snake?”

“By a krait. If you want further details, by a krait which came from Java.”

Mr. Snyder stared at him.

“How do you know?”

“I do know.”

“Did you see the snake?”

“No.”

“Then how—”

“I have enough evidence to make a jury convict Mr. Snake without leaving the box.”

“How did the snake get out of the room?”

“By the window.”

“How do you make that out? You say yourself that the window was high up.”

“Nevertheless, it got out by the window. It’s the logical sequence of events. That’s proof enough that it was in the room. It killed Captain Gunner there. And that’s proof enough that it got out of the room, because it left traces of its presence outside. Therefore, as the window was the only exit, it must have gone out that way. It may have climbed or it may have jumped, but it got out of the window.”

“What do you mean—proofs of its presence outside?”

“It killed a dog.”

“Hello! This is new. You didn’t mention that before.”

“No.”

“How do you know that it killed the dog?”

“Because analysis proved that it had died from snake-bite.”

“Where was it?”

“There is a sort of back-yard behind the house. The window of Captain Gunner’s room looks out onto it. It is full of boxes and litter of all sorts, and there are a few stunted shrubs scattered about. In fact, there is enough cover to hide any small object like the body of a dog, and that’s why it was not discovered at first.

“Katie, the maid-of-all-work at the Excelsior, came on it the morning after I had sent you my report while she was emptying a box of ashes in the yard. Nobody claimed the dog. It was just an ordinary mutt dog. I don’t suppose it belonged to anybody. It had no collar.”

“It was fortunate you happened to think of having the analysis made.”

“Not at all. It was the obvious thing to do. It constituted a coincidence, and I was on the lookout for that sort of coincidence. It supported my theory.

“Well, as I say, the analyst examined the body, and found that the dog had died of the bite of a krait.”

“But you didn’t find the snake?”

“No. We cleaned out that yard till you could have eaten your breakfast there, but the snake had gone.”

“Good Heavens! Is it wandering at large along the water-front?”

“We’ll hope it has been killed. It is not a pleasant thing to have about the streets. It must have got out through the door of the yard, which was open. But it is a couple of days now since it escaped, and there has been no further tragedy, so I guess it’s dead. The nights are pretty cold now, and it would probably have died of exposure. Anyway, let’s hope so.”

“But, for goodness’ sake, how did a krait get to Long Island, anyway?”

“There is a very simple explanation of that. Can’t you guess it? I told you it came from Java.”

“How do you know that?”

“Captain Muller told me. Not directly I mean. I gathered it from what he said. It seems that Captain Muller had a friend, an old shipmate, living in Java. They corresponded, and occasionally this man sends the captain a present as a mark of his esteem. The last present he sent him was our friend, the snake.”

“What?”

“He didn’t know he was sending it. He imagined he was sending a crate of bananas, without any extras. Unfortunately, the snake must have got in unnoticed. These unsuspected additions to crates of bananas are quite common. You must have read about them in the papers. It was only the other day that a man found a tarantula inside one.

“Well, that’s my case against Mr. Snake, and, short of catching him with the goods, I don’t see how I could have made out a stronger one. Don’t you agree with me?”

It went against the grain for Mr. Snyder to play the rôle of admiring friend to his assistant’s Triumphant Detective, but he was a fair-minded man, and he was forced to admit that Oakes did certainly seem to have solved the insoluble.

“I congratulate you, my boy,” he said as heartily as he could. “I’m bound to say when you started out I didn’t think you could do it. It looked to me like one of those cases we fail on, and keep mighty quiet about when we are printing our reminiscences. You’re a wonder.”

“Not at all. I merely used what wits God has given me, and refused to be led down blind alleys. And you must admit, Mr. Snyder, that I won through without the amateur assistance of Mrs. Pickett, which you recommended so strongly.”

Mr. Snyder looked embarrassed.

“That was just a little joke, my boy. How did you leave the old lady? I guess she was pleased?”

“She didn’t show it. She’s only half alive, that woman. She hasn’t sense enough to be pleased at anything. However, she has invited me to dine to-night in her private room, which, I suppose, is an honor. It certainly will be a bore. Still, I accepted. She made such a point of it.”

CHAPTER VI.

Mrs. Pickett Takes a Hand.

FOR some time after Oakes had gone, Mr. Snyder sat smoking and thinking. His meditations were not altogether pleasant. Oakes, he felt, after this would be unbearable as a man, and, what was worse from a professional view-point, of greatly diminished value as a servant of the agency.

To a temperament like Oakes’s, a spectacular success at such an early stage in his career would be disastrous.

Oakes as a detective—and, perhaps, as a man, too—was in the schoolboy stage. He was being educated. What he most needed at this point in his education was a failure which should keep his self-confidence in check.

That he should have succeeded so swiftly and brilliantly in this matter of the death of Captain Gunner was nothing less than a disaster.

To Mr. Snyder, meditating thus, there was brought the card of a caller. Mrs. Pickett would be glad if he could spare a few moments.

Mr. Snyder was glad to see Mrs. Pickett. He was a student of character, and she had interested him at their first meeting.

She fell into none of the groups into which he divided his fellow men and women. There was something about her which had seemed to him unique.

He welcomed this second chance of studying her at close range. She puzzled Mr. Snyder, and when any one or anything puzzled him, he liked to keep him, her, or it under observation.

She came in and sat down stiffly, balancing herself on the extreme edge of the chair in which a short while before young Mr. Oakes had lounged so luxuriously.

Her hands were folded on her lap, and her eyes had the penetrating stare which in the early periods of the investigation had disconcerted Elliott Oakes. She gave Mr. Snyder, an expert in the difficult art of weighing people up, an extraordinary impression of reserved force.

“Sit down, Mrs. Pickett,” said Mr. Snyder genially. “Very glad you looked in. Well, so it wasn’t murder, after all.”

“Sir?”

“I’ve just been seeing Mr. Oakes,” explained the detective. “He has told me all about it.”

“He told me all about it,” said Mrs. Pickett dryly.

Mr. Snyder looked at her inquiringly. Her manner seemed more suggestive than her words.

“A conceited, headstrong young fool,” said Mrs. Pickett.

It was no new picture of his assistant that she had drawn. Mr. Snyder had often drawn it himself, but at the present juncture it surprised him. Oakes, in his hour of triumph, surely did not deserve this sweeping condemnation.

“Did not Mr. Oakes’s solution of the mystery satisfy you, Mrs. Pickett?”

“No.”

“It struck me as logical and convincing.”

“You may call it all the fancy names you please, Mr. Snyder; but it was not the right one.”

“Have you an alternative to offer?”

“Yes.”

“I should like to hear it.”

“At the proper time you shall.”

“What makes you so certain that Mr. Oakes is wrong?”

“He takes for granted what isn’t possible, and makes his whole case stand on it. There couldn’t have been a snake in that room, because it couldn’t have got out. The window was too high.”

“But surely the evidence of the dead dog?”

Mrs. Pickett looked at him as if he had disappointed her.

“I had always heard you spoken of as a man with common sense, Mr. Snyder.”

“I have always tried to use common sense.”

“Then why are you trying now to make yourself believe that something happened which could not possibly have happened just because it fits in with something which isn’t easy to explain?”

“You mean that there is another explanation of the dead dog?”

“Not another. Mr. Oakes’s is not an explanation. But there is an explanation, and if he had not been so headstrong and conceited he might have found it.”

“You speak as if you had found it.”

“I have.”

Mr. Snyder started.

“You have!”

“Yes.”

“What is it?”

“You shall hear when I am ready to tell you. In the mean time try and think it out for yourself. A great detective agency like yours, Mr. Snyder, ought to do something in return for a fee.”

There was something so reminiscent of the school-teacher reprimanding a recalcitrant urchin that Mr. Snyder’s sense of humor came to his rescue.

“Well, we do our best, Mrs. Pickett. We are only human. And, remember, we guarantee nothing. The public employs us at its own risk.”

Mrs. Pickett did not pursue the subject. She waited grimly till he had finished speaking, and then proceeded to astonish Mr. Snyder still further by asking him to swear out a warrant for arrest on a charge of murder.

Mr. Snyder’s breath was not often taken away in his own office; as a rule, he received his clients’ communications, strange as they often were, calmly.

But at her words he gasped. The thought crossed his mind that Mrs. Pickett was not quite sane.

The details of the case were fresh in his memory, and he distinctly recollected that the person she mentioned had been away from the boarding-house on the night of Captain Gunner’s death, and, he imagined, could if necessary bring witnesses to prove as much.

Mrs. Pickett was regarding him with an unfaltering stare. To all outward appearances she was sane.

“But you can’t swear out warrants without evidence.”

“I have evidence.”

“What is it?”

“If I told you now you would think that I was out of my mind.”

“But, my dear madam, do you realize what you are asking me to do? I cannot make this agency responsible for the casual arrest of people in this way. It might ruin me. At the least it would make me a laughing-stock.”

“Mr. Snyder, listen to me. You shall use your own judgment whether or not to make the arrest on that warrant. You shall hear what I have to say, and you shall see for yourself how it is taken. If after that you feel that you cannot make the arrest you need do nothing.”

Her voice rose. For the first time since they had met she began to throw off the stony calm which served to mask all her thoughts and emotions.

“I know who killed Captain Gunner. I can prove it. I knew it from the beginning. It was like a vision. Something told me. But I had no proof. Now, things have come to light, and everything is clear.”

Against his judgment Mr. Snyder was impressed. This woman had the magnetism which makes for persuasiveness. He wavered.

“It—it sounds incredible.”

Even as he spoke he remembered that it had long been a professional maxim of his that nothing was incredible, and he weakened still further.

“Mr. Snyder, I ask you to swear out that warrant.”

The detective gave in.

“Very well.”

Mrs. Pickett rose.

“If you will come and dine at my house to-night I think I can prove to you that it will be needed. Will you come?”

“I’ll come,” said Mr. Snyder.

CHAPTER VII.

The Solution.

WHEN Mr. Snyder arrived at the Excelsior, and was shown into the little private sitting-room where the proprietress held her court on the rare occasions when she entertained, he found Oakes already there. Oakes was surprised.

“What—are you invited, too?” Mr. Snyder said. “Say, I guess this is her idea of winding up the case formally. A sort of old-home-week celebration for all concerned.”

Oakes laughed.

“Well, all I can say is that I hope there won’t be another case of poisoning at the Excelsior in the papers to-morrow. A woman like our hostess is certain to provide some special home-made wine for an occasion. We ought to have had the doctor wait outside with antidotes.”

Mr. Snyder did not reply.

It struck Oakes that his employer was preoccupied and nervous. He would have inquired into this unusual frame of mind, but at that moment the third guest of the evening entered.

Mr. Snyder looked curiously at the newcomer. The big German had a morbid interest for him. Many years in the exercise of a profession which tends to rob its votaries of sentiment had toughened Mr. Snyder, but there was something macabre about the present circumstances which struck home to his imagination.

He was not used to this furtive work. Till now he had met his man in the open as an enemy, and it struck him as an unpleasantly gruesome touch that he must presently sit at meat with one whom it might be his task to send to the electric chair.

He wished Mrs. Pickett could have arranged things otherwise; but she was his employer, and when on duty in the service of an employer Mr. Snyder was wont to sink his personal feelings.

Captain Muller, the German, was an interesting study to one in the detective’s peculiar position.

It was not Mr. Snyder’s habit to trust overmuch to appearances, but he could not help admitting that there was something about this man’s aspect which brought Mrs. Pickett’s charges out of the realm of the fantastic into that of the possible.

Here, to a student of men like Mr. Snyder, was obviously a man with something on his mind. That that something need not necessarily be murder, or any crime whatsoever, the detective admitted.

But under the circumstances the fact that Captain Muller was in a highly nervous condition was worthy of notice if nothing more.

There was something odd—an unnatural gloom—about the man. He bore himself like one carrying a heavy burden. His eyes were dull, his face haggard.

The next moment the detective was reproaching himself with allowing his imagination to run away with his calmer judgment. It mortified him to think that he was permitting himself to be carried away by a train of thought precisely as Oakes would have been.

Nevertheless, whether it was a real oddness or whether Mrs. Pickett’s words had overstimulated his fancy, there certainly did seem something odd about the German.

Mr. Snyder disposed himself to watch events.

At this moment Oakes gave evidence that he, too, had been struck by the expression of the other’s face.

“You’re not looking well, captain,” he said.

The German raised his heavy eyes.

“I do not sleep goot.”

The door opened and Mrs. Pickett came in.

To Mr. Snyder one of the most remarkable points about a dinner, which for the rest of his life had a place of its own in his memory, was the peculiar metamorphosis of Mrs. Pickett from the brooding, silent woman he had known to the polished hostess.

Oakes, who had dealt with her in her official capacity of owner and manager of the boarding-house, was patently struck by the change. Mr. Snyder found himself speculating as to the early history of this curious old woman who was so very much at ease at the head of her own table.

Oakes, that buoyant soul, was unable to keep his surprise to himself. He had come prepared to steel his stomach against home-made wine, absorbed in grim silence, and he found himself opposite a bottle of champagne of a brand and year which commanded his utmost respect and a pleasant old lady whose only aim seemed to be to make him feel at home.

Beside each of the guests’ plates was a neat paper parcel. He picked his up.

“Why, ma’am, this is princely! Souvenirs! I call this very handsome of you, Mrs. Pickett!”

“Yes, that is a souvenir, Mr. Burton. I am glad you are pleased.”

“Pleased? I am overwhelmed, ma’am!”

“You must not think of me simply as the keeper of a boarding-house, Mr. Burton. I am an ambitious hostess. I do not often give these little parties, but when I do I like to do my best to make them a success. I want each of you to remember this dinner of mine.”

“I’m sure I shall.”

Mrs. Pickett smiled.

“I think you all will. You, Mr. Snyder.” She paused. “And you, Captain Muller.”

To Mr. Snyder there was so much meaning in her voice as she said this that he was amazed that it conveyed no warning to the German.

Captain Muller, however, was already drinking heavily. He looked up when addressed and uttered a sound which might have been taken for an expression of polite acquiescence. Then he filled his glass again.

Mr. Snyder, eying his hostess with a tense watchfulness which told him that his nerves were strung to their utmost, fancied that her eyes gleamed for an instant with the sinister light.

It faded next moment, as she turned to speak to Oakes, who was still fingering his parcel with the restless curiosity of a boy.

“Do we open these, ma’am?”

“Not yet, Mr. Burton.”

“I’m wondering what mine is.”

“I hope it will not be a disappointment to you.”

A sense of the strangeness of the situation came over Mr. Snyder with renewed force as the meal progressed. He looked round the table and wondered if an odder quartet had ever been assembled.

Oakes, his fears that the dulness of this dinner-party would eclipse the dulness of all other dinner-parties in his experience, miraculously relieved, was at peace with all men. He was in high spirits and waxed garrulous over his wine.

Mr. Snyder could read his mind easily enough. It was when he attempted to guess at the thoughts of his hostess and the German that he was baffled.

What was that heavy man with the dull eyes thinking of as he drained and refilled his glass? And the old woman?

She had slipped back, once the party had begun to progress smoothly, into something of her former grim manner, and conversation at table had practically developed into a monologue on the part of the unconscious Oakes.

As for Mr. Snyder himself, he felt mysteriously deprived of his usual healthy appetite and simultaneously of the easy geniality which distinguished him. He sat and crumbled bread, nervously watchful.

Oakes picked up his souvenir again. He had been fiddling with it at intervals for the past quarter of an hour.

“Surely now, ma’am?” he said plaintively.

“I did not want them opened till after dinner,” said Mrs. Pickett. “But just as you please.”

Oakes tore the wrapper eagerly. He produced a little silver match-box.

“Thank you kindly, ma’am,” he said. “Just what I have always wanted.”

Mr. Snyder’s parcel revealed a watch-charm fashioned in the shape of a dark-lantern.

“That,” said Mrs. Pickett, “is a compliment to your profession.” She leaned toward the German. “Mr. Snyder is a detective, Captain Muller.”

The German looked up.

It seemed to Mr. Snyder that a look of fear lit up his heavy eyes for an instant. It came and went, if indeed it came at all, so swiftly that he could not be certain.

“So?” said Captain Muller.

He spoke quite evenly, with just the amount of interest which such an announcement would naturally produce; but Mr. Snyder was conscious of a return of his old feeling of distrust for the man.

He had been fighting against this all the evening, for he had a professional horror of approaching any case in a biased frame of mind. He was trying his hardest not to prejudge this suspect, but he found himself wavering.

“Now for yours, captain,” said Oakes. “I guess it’s something special. It’s twice the size of mine, anyway.”

It may have been something in the old woman’s expression as she watched the German slowly tearing the paper that sent a thrill of excitement through Mr. Snyder.

Something seemed to warn him of the approach of a psychological moment. He bent forward eagerly. Under the table his hands were clutching his knees in a bruising grip.

There was a strangled gasp, a clatter, and onto the table from the German’s hands there fell a little harmonica.

In the silence which followed all the suspicion which Mr. Snyder had been so sedulously keeping in check burst its bonds.

There was no mistaking the look on the German’s face now. His cheeks were like wax, and his eyes, so dull till then, blazed with a panic and horror which he could not repress. The glasses on the table rocked as he clutched at the cloth.

Mrs. Pickett spoke.

“Why, Captain Muller, has it upset you? I thought that, as his best friend, the man who shared his room, you would value a memento of Captain Gunner. How fond you must have been of him for the sight of his harmonica to be such a shock.”

The German did not speak. He was staring fascinated at the thing on the table.

Mrs. Pickett turned to Mr. Snyder. Her eyes, as they met his, were the eyes of a fanatic. They held him.

“Mr. Snyder, as a detective, you will be interested in a curious affair which happened in this house a few days ago. One of my boarders, Captain Gunner, was found dead in his room—the room which he shared with Captain Muller.

“I am very proud of the reputation of my house, Mr. Snyder, and it was a blow to me that this should have happened.

“I applied to an agency for a detective, and they sent me a stupid boy, with nothing to recommend him except his belief in himself. He said that Captain Gunner had died by accident, killed by a snake which had come out of a crate of bananas. I knew better.

“I knew that Captain Gunner had been murdered.

“Are you listening, Captain Muller? This will interest you, as you were such a friend of his.”

The German did not answer. He was staring straight before him, as if he saw something invisible to other eyes.

“Yesterday we found the body of a dog. It had been killed, as Captain Gunner had been, by the poison of a snake.

“The boy from the detective agency said that this was conclusive—that the snake had escaped from the room after killing Captain Gunner and killed the dog. I knew that was impossible, for, if there had been a snake in that room it could not have got out.

“It was not a snake that killed Captain Gunner; it was a cat.

“Captain Gunner had a friend. This man hated him. One day, in opening a crate of bananas, the friend found a snake and killed it. He took out the poison.

“He knew Captain Gunner’s habits; he knew that he played a harmonica.

“This man had a cat. He knew that cats hated the sound of the harmonica. He had often seen this particular cat fly at Captain Gunner and scratch him when he played.

“He took the cat and covered its claws with the poison. And then he left it in the room with Captain Gunner. He knew what would happen.”

Oakes and Mr. Snyder were on their feet. The German had not moved. He sat there, his fingers gripping the cloth.

Mrs. Pickett rose and went to a closet. She unlocked the door.

“Kitty!” she called. “Kitty! Kitty!”

A black cat ran swiftly out into the room.

With a clatter of crockery and a ringing of glass the table heaved, rocked, and overturned as the German staggered to his feet. He threw up his hands as if to ward something off. A choking cry came from his lips.

“Gott! Gott!”

Mrs. Pickett’s voice rang through the room, cold and biting:

“Captain Muller, you murdered Captain Gunner!”

The German shuddered. Then mechanically he replied:

“Gott! Yes, I killed him.”

“You heard, Mr. Snyder,” said Mrs. Pickett. “He has confessed before witnesses. Take him away.”

The German allowed himself to be moved toward the door. His arm in Mr. Snyder’s grip felt limp and lifeless.

Mrs. Pickett stooped and took something from the débris on the floor. She rose, holding the harmonica.

“You are forgetting your souvenir, Captain Muller,” she said.

(The end.)

Printer’s errors corrected above:

In Ch. II, magazine had “pinocle”; corrected to “pinochle”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums