Cassell’s Magazine, July 1907

I SHOULD like to start by saying that all this happened two days after my sixteenth birthday, when my hair was still down, so that I hadn’t anything to live up to, and it didn’t matter what I did—or not much, at any rate. That’s how it was.

It all began at breakfast on the Saturday. We were going to play Anfield that afternoon. Anfield is a town a few miles off, and the match is one of the best that Much Middlefold plays. So that I wasn’t surprised that father was annoyed when he got the curate’s letter. He opened it at breakfast, just after I had come down. I was pouring out the coffee when I heard him snort in the way he always does when anything goes wrong.

I said, “What’s the matter, father dear?”

“Here’s a nice thing,” he said, waving the letter. “Morning of match—most important match—team not any too strong—wanting everyone we can possibly get, and here’s Parminter writing to say that he can’t play!”

“Can’t play?”

Mr. Parminter was our best bowler. He had nearly got his blue at Cambridge. Father once told me that the Vicar advertised for a curate, and said that theology didn’t matter, but he must have a good break from the off; and I thought it was true till I happened to find an old number of Punch with the same thing in. But, anyhow, Mr. Parminter had got a break from the off. Whenever we won a match it was nearly always through his bowling. He bowled very fast. A man we know once said that there was much too much devil in his bowling, considering that he was a clergyman.

“Why can’t he play?” I asked.

“The wretched man,” said father, “was at the school treat yesterday, and fell out of the swing and sprained his right wrist. Would have let me know last night, he says, but thought it might be better in the morning. Finds it impossible to move his arm without considerable pain; is dictating this letter to his housekeeper, and hopes that I shall be able to fill his place without difficulty, even at such short notice. Fill his place, indeed! And I hear that Anfield are strong in batting this year, though weak in bowling.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I suppose we must play young Hardy. He’s quite incompetent, but he is the only one. Unless you can think of anybody else, Joan?”

I thought.

“No,” I said, “I can’t, father.”

And it was not till the end of breakfast that I did. And even then I wasn’t sure that he would be able to play. The person I thought of was my cousin—or, rather, he’s only a sort of cousin, about twice removed. His name was Alan Gethryn, and he was at school at Beckford, which is quite near to us, if you bicycle. He had sometimes been to stay with us on Visiting Sundays. I knew he was good, because he had taken a lot of wickets for the Beckford team in matches. So I suggested him.

Father brightened up.

“That’s an uncommonly good idea, Joan,” he said. “Beckford always have a pretty useful sort of side—they coach ’em well there—and if Alan’s in the team he ought to be a decent player.”

“He’s in the team all right,” I said. “He was top of the bowling averages last year.”

“This is excellent. I wonder if we could get him.”

“And I could easily bike over and ask him, father,” I added. “Shall I? And if he can play, I could wire to you, so that you would know in time. If he can’t play, you can always get Hardy.”

Father said, “Very well,” so I got my bicycle, and, after sending off a wire telling Alan to meet me outside the school-gates during the quarter of an hour interval in the morning I went off. I got to the school at twenty to eleven, and rode up and down outside, and presently Alan strolled out.

“Hullo!” he said.

“I say, Alan,” I said, “would you like a game this afternoon for Much Middlefold?”

“A what?” he said.

“A game. Father sent me over to ask you if you’d play. Mr. Parminter has sprained his wrist, so we want a bowler. It’ll be an awfully jolly match, and you could have tea with us, and get back afterwards.”

He looked thoughtful.

“Difficulty is, you see, the corps are going off on a field-day this afternoon, and I shall be in charge here. Got to take roll-call, and so on.”

“When’s roll-call?”

“Four.”

“Oh, I say. Then you can’t come?”

“Wait. Let’s think this thing over. Reece would take roll-call all right if I asked him, so that disposes of that. It would be out of bounds, of course, going to your place, but I don’t see who’s to know. So there goes that, too. I could change here and bike over. There wouldn’t be any difficulty about that. And I happen to know that Leicester is going to be out of the way all the afternoon. So it’s all right. I shall be able to come.”

“Oh, good!” I said. “Who’s Leicester?”

“My house-master. Under ordinary circs he’d be at roll-call while I ticked off the names, and I’d have to hand the list to him then. But he was telling us this morning at breakfast that he was going to spend the afternoon looking at an old church somewhere. He’s keen on antiquities, you know, and brass-rubbing, and all that sort of thing. So he won’t be on hand. All I’ve got to do is to get back here by about six or half-past and give him the list then.”

After lunch Alan came.

“Ah, Alan, my boy,” said father. “Glad you were able to turn up. Had lunch? That’s right. I’ve got to go down to meet these Anfield fellows. You come on later. We don’t start till two-thirty. You know your way down to the ground, don’t you? See you there.”

He went out of the room, carrying his cricket-bag, and returned almost at once.

“Pretty nearly forgotten it, by gad!” he said. “I say, Joan, there’s something I want you to do for me. It won’t make you miss more than an over or two of the game. I met a man at the Burley-Grey’s some time back, and we got talking about antiquities—seems he’s keen about them—so I gave him a general invitation to come over here and let me show him over our church. He has rather unfortunately chosen to-day for his visit. I had his letter at breakfast, only this Parminter business put it out of my mind. I wish you would just show him the way to the church when he comes, Joan. He will arrive here at about three on his bicycle. Just explain that I can’t possibly get away. You needn’t stay with him, of course. Simply take him to the church, and leave him. He won’t want conversation. He is going to rub brass, or some such thing. I don’t know what he means—it doesn’t sound a very amusing way of spending a fine summer’s afternoon—but that is what he said. Just tell him there will be tea here at about half-past four if he cares to turn up for it. But I should not think he would.”

I looked at Alan in a perfect panic. It could not be a coincidence.

“What is his name, father?” I asked.

Father actually had to think before he could tell me. I could have told him at once.

“Leinster? Leicester—that’s it. Leicester. Mrs. Burley-Grey introduced him to me.”

Father went out again, and Alan and I were alone. I waited till I heard the front door shut.

“This,” Alan said, “wants thinking out. Ginger-beer may help.” He poured some into a glass and drank it, but it didn’t seem to act. He offered no suggestion.

“Oh, do say something, Alan,” I said. “What are we going to do? Will you go back?”

“And leave your father in the cart? Not much. I’m a fixture for the afternoon if the place was crawling with Leicesters. Am I down-hearted? No! . . . On the other hand, it’s rather a brick, this happening. The thing we want to do is to keep him off the field altogether, if possible, at any rate as long as we can. I don’t see why he shouldn’t be perfectly happy rubbing brass all the afternoon. Why not leave him there and risk it?”

“I couldn’t. We must think of something better.”

“Well, you have a shot. I’m getting a headache. I’ll tell you one thing I’ll do. I’ll ask your father if he wins the toss to put them in first, as I have to leave early. That’ll help a bit. Hullo, it’s twenty past! I shall have to rush. I leave you in charge of this thing. Knock him on the head and tie him up. Lock him in the church and bag the keys.”

I saw him to the door, and watched him bike off in the direction of the field. Then I went back to the dining-room to think it all over.

There was a ring at the front door about three o’clock, and I thought it was bound to be Mr. Leicester. A bicycle was against the pillar at the front of the steps, and a thin, elderly man was standing on the top one, leaning down and picking trouser-clips off himself. He stood up when I opened the door, and looked at me inquiringly through a pair of gold-rimmed glasses. He had a very mild, kind face, rather like a sheep.

“Oh, are you Mr. Leicester?” I said. “Because father’s very sorry he’s had to go off to the match—we’re playing Anfield to-day—and I’m going to show you to the church.”

“I shall be very much obliged, if it would not be giving you too much trouble. I fear I have called at an inconvenient time.”

He had, of course, but I couldn’t say so.

I said, politely, “Not at all.”

We put his bicycle in the stables and set off across the fields to the church, about half a mile away.

Mr. Leicester didn’t talk much while we were walking. I think he didn’t quite know what to say to me. And I was wondering so much what I was to do to keep him from meeting Alan that I didn’t talk much either.

When we got in sight of the church he brightened up.

“How very beautiful!” he said, standing quite still and pointing, like a dog when it smells a bird. “How picturesque! That grey stone has a delightfully soothing effect against the green of the trees, with the white road winding behind it. How truly picturesque!”

I said, “Yes, isn’t it top-hole!”

He said, “I beg your pardon?”

I said, “Not at all.”

And we went on.

As soon as we got inside he pointed again. I saw that he was looking at the old brass tablet at the end of the aisle, the one that was put there by the widow of a man who died in Edward III.’s time. He put a large piece of paper, which he had been carrying, on it, and knelt down and began to scratch at it with something black. I locked the door, and came and sat in a pew near, and watched him. He scratched and scratched away, and I sat and sat till I heard the clock strike four. I almost wished I had gone and left him, for I was dying to see the match, and I was pretty sure that he would have stopped there.

At about a quarter past four it suddenly occurred to me that there wasn’t any need for me to go on sitting there, because the door was locked and I had the key, so he couldn’t get out without my knowing. So I got up and began to explore. I had never been anywhere in the church except in our pew, and in the vestry, at a christening, so there was lots to see. I wandered about, and at last I saw a little door with some steps behind it. I went up and up, till I found myself looking into a great sort of loft place full of ropes, which I knew must be the belfry. The steps went on round the corner. I started off again, and came to a trap-door. I pulled this down, and there I was on the roof of the tower, with the loveliest view in front of me you ever saw.

I could see the cricket-field, with little specks of white on it. If I had had some glasses I could have watched the match beautifully.

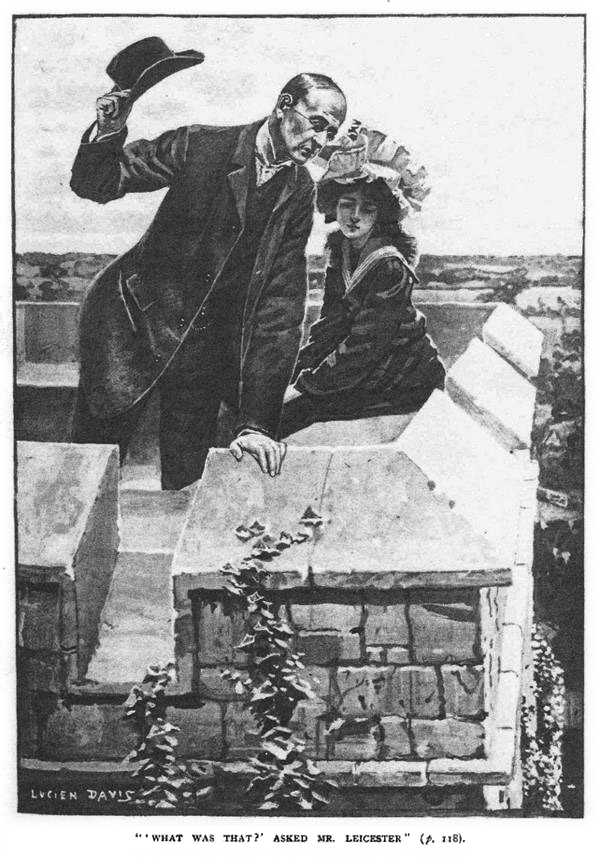

I sat there looking at the view till I heard a scraping on the steps, and Mr. Leicester’s head bobbed up through the trap-door. He beamed at me, panting rather hard, and then pulled himself up.

“Ah! the roof!” he said. “What a delightful view! I suppose that is the cricket-field, with the little white figures beyond the stream. How delightfully cool the breeze is up here! Really, one is almost sorry to have to descend into the heat below.”

I didn’t like this. It sounded as if he were going.

“Why not stop up here?” I said.

“It would certainly be pleasant. But I should like to see your father before I return to Beckford. I must thank him for the great treat he has given me this afternoon in allowing me the privilege of seeing this beautiful old church.”

I said, in a hurry, “Oh, it doesn’t matter about father, really. I mean, of course, he may be batting or anything. He’ll probably be very busy.”

“I should like very much to see him bat,” said Mr. Leicester benevolently.

“Aren’t you going on doing the brass?” I asked.

“I think not to-day—not to-day. I find the continuous stooping a little trying for the back, and I have obtained a very satisfactory impression. I think that we had better be going down, if you have no objection.”

So I dropped the keys over the parapet, and they fell with a rattle on the gravel path. It was a desperate measure, as they say in the books, but I couldn’t think of anything else.

“What was that?” asked Mr. Leicester.

“Oh, I say,” I said, “I’m awfully sorry. I’ve dropped the keys!”

“We had better go down and recover them.”

“But don’t you see? We can’t get out. The door’s locked.”

Mr. Leicester’s mouth opened feebly.

“We must sit here and wait for someone to come and let us out. The worst of it is everybody’s at the match. Still, we can’t stay here for ever, because when father finds I don’t come in to dinner—”

“Dinner! In to dinner! My dear young lady, it is imperative that I should be back at Beckford at half-past six!”

“I’m awfully sorry,” I said, “but unless somebody comes along —”

“Is there no other way out?” he asked.

“I’m afraid not,” I said. “It was careless of me to drop them.”

“Pray, pray do not distress yourself. These accidents happen to everyone.”

I have always thought it awfully nice of him not to be angry, because he might easily have been. I know I should have been if somebody had kept me locked in a place when I wanted to get out.

We sat and waited there for about another quarter of an hour. It was jolly awkward. I didn’t know what to say. It was no good talking about the view, because he was too worried by the thought of not being able to get back in time to care much about anything else.

“I really think,” he said at last, “that we had better shout for assistance.”

It is all very well to make up your mind to shout for assistance, but it isn’t easy to think what to shout. We both began at the same time. He cried, “Help!” I shouted “Hi!”

We didn’t make very much noise really, because he had a weak voice and I didn’t shout my loudest, as I was afraid of making myself hoarse. But it sounded quite loud in the stillness.

“I fear it is hopeless,” said Mr. Leicester. “The neighbourhood appears completely deserted.” But just then, as I was hoping that it was all right and that we shouldn’t be let out till Alan had got safely home, I heard somebody shuffling along in the road, and singing. It was like the bit in “The White Company,” where they’re on the burning tower and can’t get down and hear the archers singing the Song of the Bow in the distance. Only they were pleased, and I wasn’t.

Mr. Leicester jumped up and leaned over the side and shouted quite loud. The singing stopped.

“ ’Ullo! ’ullo!” said a voice, and the gate clicked. I looked over Mr. Leicester’s shoulder, and saw a tramp standing below, shading his eyes with his hand.

“My good man,” said Mr. Leicester, “I should be very much obliged if you would let us out.”

“Wot’s the little gime?” said the man.

“We are locked in, and cannot get out. You will find the key a little to your left, lying on the gravel path. Take it and unlock the door.”

The tramp was a man of business.

“Wot do I make outer this?” he wanted to know.

“I will give you a shilling,” said Mr. Leicester.

“ ’Arf a dollar, guv’nor, ’arf a dollar. Liberty, the bloomin’ ’eritage of the bloomin’ Briton, thet’s wot I’m going to give yer. It’s cheap at ’arf a dollar.”

“Very well,” said Mr. Leicester.

We went down the steps, and presently we heard the key in the lock and the door opened.

I wasted as much time as possible walking home, and we did not get to the field till about half-past five. I was faint for want of tea. Father and Thoms, the son of the vicar’s gardener, were batting. Just as we came on to the ground father hit a beautiful four to leg. I raced on ahead of Mr. Leicester to warn Alan. I found him in the pavilion—at least, we call it a pavilion; it’s really only a sort of shed. There are two floors. On the top one the scorer sits, but not often anybody else. Alan was there, with his pads on.

“Hullo!” he said, “what a time you’ve been. What have you been doing? Where’s Leicester?”

I told him all about it in a whisper, so that the scorer shouldn’t hear. He seemed to think it funny, but he remembered to thank me. If he hadn’t, after all I had been through, I don’t know what I should have done.

“Where’s he now?” he asked.

“He would come here with me. He’s somewhere on the ground.”

“That’s rather awkward. Half a second! I’ll go down and spy out the land.”

He went down the ladder, but came up again almost at once. He shut down the trap-door very quietly, and came and sat at the back of the room.

“That was a close thing,” he said, grinning. “He’s sitting on a bench down there, watching the game. I nearly charged into him.”

“What are you going to do?”

“Sit tight. That’s the programme at present. I say, though, this is about the tightest place I’ve ever been in. I’m in next! Bit awkward, isn’t it? If either Thoms or your pater gets out, I’m pipped; I must go down. But perhaps he won’t stop.”

“He will,” I said miserably. “He’s waiting to see father, to thank him for asking him to come to the church.”

Alan grinned again. I really believe he enjoyed it.

“Well, I don’t see that we can do anything. It’s just possible that your pater may knock off the runs. He’s playing a ripping game.”

“It’s the other man I’m worried about,” said Alan. “He’s a rabbit from the old original hutch. Look at him scratching away at the fast man.”

I looked at him and wondered why they could not get him out. Every ball seemed to go just above or just to one side of the wicket. Then it was the end of the over, and father had the bowling. The first ball was a full-pitch, and he hit it right into the shed. We could hear it bumping against things down below.

“Well hit, sir,” said Alan. “Let’s hope that’s killed Leicester.”

Somebody threw the ball back. The bowler bowled again, and father drove it over his head. They got three for it.

“Oh, don’t run odd numbers,” said Alan. “Now the rabbit’s got the bowling, and he’ll be shattered to a certainty.”

Every ball looked as if it was going to bowl that wretched Thoms. The first two hopped over his wicket. The next was to leg, and he swiped at it but missed. The last of the over was a half volley. He mowed at it, and it hit the top of his bat and up it went into the air, the easiest catch for point you ever saw.

Alan got up with a resigned expression, and began to take off his blazer.

“He can’t miss that,” he said. “The young hero will now walk with a firm step to his doom.”

Point was standing with his hands behind his back and a smile on his face, waiting for the ball to come down. It came, and he—missed it. I was quite sorry for him, especially as all the village boys shouted and jeered. (They will do it. We can’t get them not to.)

“I shouldn’t have thought,” said Alan, sitting down again, “that a man could drop a sitter like that if he’d been paid for it. Now it ought to be all right.”

“What are you going to do about getting back?” I asked. “If you both start at the same time he’s sure to see you.”

“That’s true. I’d forgotten that. This business seems to develop difficulties while you wait. Where’s his bike?”

“In the stables.”

“Mine’s just round behind the pav. So I shall get a sort of start. Can’t you keep him hanging about a bit, till I’ve got well off?”

“I’ll try.”

A ripping idea suddenly occurred to me. I got up.

“Where are you off to?” asked Alan.

“The stables,” I said. “Good-bye. I shan’t see you again before you go. Thanks awfully for playing.”

“Thanks for the game. Jolly good game. There’s another four. Only six to win now.”

I went down the ladder and ran across the ground. When I got to the gate I heard tremendous yelling from the village boys, and I saw them all going back to the pavilion, so I knew that we had won.

After I had been to the stables, I went back to the field, and met father and Mr. Leicester coming to our house. They had just passed the lodge gates.

“Well, Joan,” said father, “we won, you see, thanks to—”

I said, quickly: “Thanks to you, father dear. Didn’t he bat well, Mr. Leicester.”

“Exceedingly vigorously,” said Mr. Leicester. “Exceedingly vigorously. But I must really hurry away. We left the bicycle in the stables, did we not?”

But when we got to the stables we found the back tyre absolutely flat.

Mr. Leicester’s face lengthened.

“How very unfortunate,” he said.

“Great nuisance,” said father.

I said, “What an awful pity!”

“Particularly,” said Mr. Leicester, “as I omitted to bring my repairing outfit with me. It was a deplorable oversight.”

“Oh, that’s all right,” said father. “My daughter has whatever you will want. Run along and get the things, Joan.”

It was about ten minutes before I got back. I found them looking at the bicycle in silence. I put down the repairing stuff. Then I said, “You know, it may not be a puncture, after all. Perhaps the valve has worked loose. Mine sometimes does.”

“I hardly think,” said Mr. Leicester, “that that can be the——why, yes, you are perfectly right: it is quite loose. I wonder how that can have happened?”

I said, “I wonder.”

Note:

The anecdote about cricketing qualifications for a curate was published in the Daily Telegraph of July 31, 1900, and was made famous by a Punch cartoon of August 15, 1900.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums