Land and Water Illustrated, November 26, 1904

The Cricketer in Winter.

This has been called a remedial age, an age of keys for all manner of locks, but how few have been the attempts, up to the present, to solve the great unemployed problem—what is a cricketer to do in winter? It is becoming more serious every year. And if, as is almost certain to be the case, the recovery of the Ashes leads to an increased zeal for the game, there is no knowing what will happen in 1905 or 1906.

People who like to dismiss the profoundest sociological questions after a moment’s thought will probably say that the cricketer can amuse himself in winter with football, or even hockey. They do not understand the cricketer’s mind. He is not to be put off with the “This is just as good, sir,” against which manufacturers of patent foods and soaps so strenuously warn their clients. Football is very well in its way. An excellent game. But, after all, only a game. What he wants is cricket.

Hitherto his chief solace has been Wisden. And, as far as a mere book can fill the void, Wisden meets the case. There is a rare pleasure in looking up the scores of matches, and poring over the photographs of the five players of the season on the front page. But even this palls after a time. It is good as far as it goes, but it does not go far enough. Something more strenuous is required. So the cricketer takes his bat from the bag and oils it pensively, or practises drives, draws, and cuts in front of a pier-glass, to the detriment of his bedroom furniture. Later on, if it is not too wet, he may play stump-cricket in the back garden with a walking-stick and a tennis-ball. There has recently been made a more ambitious attempt to provide the cricketer with employment by boarding over the swimming-bath at the St. Bride’s Institute, erecting thereon two nets, and laying down cocoa-nut matting. The floor is long enough to allow the bowler a run of a few yards, and the result is as near to success as any makeshift can be. Net practice is the prose of cricket. Indoor net practice is very lame and halting prose indeed. It was not to be expected that these nets would be perfect. There were bound to be drawbacks. But as at present there seem to be more drawbacks than are absolutely unavoidable, I will proceed to a brief indictment.

Imprimis, the light. What there is of it is excellent, but there is not enough. For any game but cricket the place would deserve to be described as brilliantly lighted. But to play cricket with any comfort one needs more. A few more globes towards the middle of the building would be an improvement. At present the light is perhaps the trickiest in which the game has ever been played. There is a sense of unreality about the whole performance. It is like playing cricket in a dream, which becomes a nightmare when, as occasionally happens even on the best-behaved matting, the bowler finds a spot. Standing at the batting end one sees the bowler run to the mark and deliver. Then the ball totally disappears. Another second and it is visible again, but it is now so close that the batsman is obliged to play for it, so to speak, “all anyhow.” This may be good training for matches on gloomy days, but it is harassing for the nerves.

Another queer effect of the light is felt by the bowler. Just as the ball disappears on leaving the bowler’s hand, so does it vanish directly the batsman has hit it. For more than half a second after the batsman has made his stroke, there is entire uncertainty as to the direction the ball has taken. Perhaps it flies off towards point or the slips. Occasionally it comes humming back down the pitch, and the little knot of bowlers scatter and allow it to crash against the back wall. Some day somebody is going to be mortally wounded by a hot return. But it will be a glorious death. “Here lies a cricketer. He died while doing his duty.” The pioneer always has a poor time.

My next grumble is one that may be laid to heart. It has to do with the bowlers. Owing to the fact that two dozen cricket balls were destroyed in the first week, battered to pieces by the hard wicket, it has been found necessary to substitute composition balls; and, as everybody knows, the amount of “stuff” it is possible to “get on” with a composition ball on a matting pitch is prodigious. It therefore behoves the bowler to bowl with a certain amount of self-repression. He should try to remember that he is not playing in a match, and should eschew those fast short balls on the off, which whip in and pulverise the unfortunate batsman before he knows what has happened to him. “Pitch ’em up” is the golden rule in the composition-cum-matting game.

Thirdly, the wicket. At present it is black against a white background. It would show up better if it were white against a black background. The effect of the white wall at the batsman’s end is too dazzling.

Fourthly and lastly, it cannot be necessary to keep the temperature at such a height. Pleasant as the change is after the rawness of the atmosphere outside, it speedily becomes oppressive, especially after a bowler has sent down an over or two of his fastest. Cricket loses its charm when played in a hothouse.

But in every other way the conditions are perfect. The wicket is as true as possible, and the ball rarely rises to more than half the height of the stumps. Of the two wickets the one next to the entrance is considerably the better, as the manner in which the lights are arranged makes it easier to get an accurate sight of the ball there than on the further pitch, where the batsman has to stand with his back to the light. Also there is a “spot” on the latter pitch off which the ball springs—and stings—like a snake.

If the cricketer wearies of his Wisden on his return home after a visit to the St. Bride’s Institute, he may extract some amusement from a game which is a blend of Dr. Grace’s Indoor Cricket and another similar game. A cardboard barrier is placed round the table. The wickets are on a wooden pitch covered with green baize. There are fieldmen on concave tin stands. If the ball goes into one of these stands and stays there, the batsman is out. The bowling is done with a wooden marble and an iron spring. The excitement of playing a big innings is tremendous, but as a rule the bowler has the upper hand. In such ways may the cricketer pass his winter, and feel that his time, though not spent wholly as he could wish, has nevertheless not been altogether wasted.

P. G. Wodehouse.

Ashes: a venerated symbolic trophy of the England-Australia cricket rivalry.

St. Bride’s Institute: founded in 1891 and opened in 1894 in Bride Lane just off Fleet Street as a cultural, educational, and recreational center for the printing and publishing trade. The space over the swimming pools is now a theatre: see their web site.

Dr. Grace’s Indoor Cricket: A tabletop game invented by W. G. Grace, one of the most prominent cricketers of the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

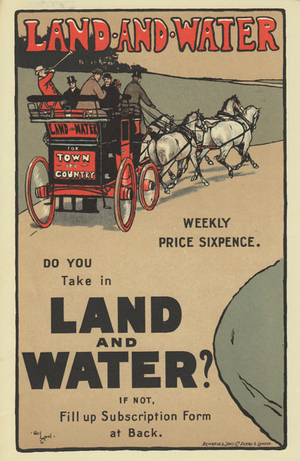

Land and Water was founded in 1866 by the naturalist Frank Buckland. “Illustrated” was added to the title in 1894. Cecil Aldin worked for the journal as a correspondent and illustrator, and painted the 1903 advertisement at left. Wodehouse’s story “Gone Wrong” appeared in The Cecil Aldin Book in 1932.

Land and Water was founded in 1866 by the naturalist Frank Buckland. “Illustrated” was added to the title in 1894. Cecil Aldin worked for the journal as a correspondent and illustrator, and painted the 1903 advertisement at left. Wodehouse’s story “Gone Wrong” appeared in The Cecil Aldin Book in 1932.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums