Pearson’s Magazine (UK), January 1906

I was standing on the pavement, drinking in the fresh air, when the dilapidated man spoke to me. Brown had finished telling me his favourite story on the doorstep; but under the influence of the bracing atmosphere of Soho I was rapidly recovering, and was preparing to retire, when the man in the very old frock-coat touched me on the shoulder.

“The rain keeps off,” he began.

I wished he would imitate the rain.

“A word with you,” he said.

“I have no small——” I was beginning, when he proceeded with that quiet determination which marks the born bore to tell me the following narrative:

“To look at George Pennefather Wilkinson now,” he said—he had rather a pretty narrative style—“nobody would think that he was once in possession of a comfortable berth in a City office, heir to a rich and invalid uncle, and engaged”—here he dashed away a tear—“to a wealthy and beautiful young lady of a family highly respected in South Balham. Yet such was the case. And look at me now? What brought me to this? Did I drink?”

“I suppose so,” I said, as he seemed to expect an answer.

“If we except a small raspberry vinegar at lunch—no. Was I dishonest? No. Then why, you ask, am I now so entirely, if I may so express it, in the soup? Why, you ask?”

“I don’t,” I said.

He proceeded without noticing the interruption.

“It was because I was honest. Nothing else. They say honesty is the best policy. Bah! Listen.”

I listened. It occurred to me that if this unfortunate creature had really a story to tell, I might steal it and make a bit. Besides, it would have been unkind to have denied him the pleasure of pouring out his troubles.

“I heard you laughing at that story1 your friend was telling you about the bit of chalk and the man who dreamed that he went to Heaven. It was that that induced me to speak to you. The lamp-light flashed on your face as he told you the story, and I saw that it was contorted with pain.”

I have often wondered since what lamp-light looks like when contorted with pain.

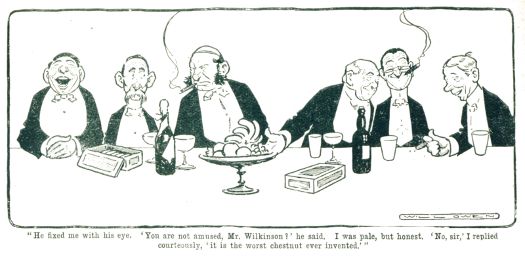

“That story was my ruin. Listen, I have told you that I was in a City office. By the exercise of great pains I had risen to the position of head clerk. One night the boss invited the staff to dinner. I sat on his right. After dinner, as we smoked our cigars, he said: ‘Talking of dreams’—we had been discussing Mr. Chamberlain and the mention of Joseph of course suggested dreams—‘I had a curious one last night. I dreamed I went to Heaven.’ At this point one of the younger clerks, thinking that that was a joke, laughed loudly. He was dismissed next day without a character. I will not inflict the whole story upon you, especially as you have just heard it from your friend. Suffice it to say that, when he concluded, the table was in a roar. I alone sat silent. He fixed me with his eye. ‘You are not amused, Mr. Wilkinson?’ he said. I was pale but honest. ‘No, sir,’ I replied firmly. ‘Perhaps you have heard the story before?’ he said icily. ‘Sir,’ I answered courteously, ‘it is the worst chestnut ever invented. I heard it for the first time from my nurse in my cradle, and the present occasion is the four hundred and sixty-fifth on which I have had to listen to it.’ ‘Jones,’ he said, turning pointedly to the man on his left, ‘what are your views on Fiscal Reform?’ And the subject was changed. Next day I was informed that the firm had no further use for my services.

“Wandering disconsolately homewards, I met my Uncle Robert. He was in high spirits, and insisted on my lunching with him. After luncheon he said: ‘Talking of dreams’—we had been eating lobster salad, which, of course suggested dreams—and out came the story again. ‘Why, damme, George,’ he said, ‘you aren’t laughing. No sense of humour, what?’ ‘Uncle,’ I replied, ‘I cannot tell a lie. That is the four hundred and sixty-sixth time I have heard that story.’ ‘Bill, waiter,’ he said with awful calm. ‘George, my boy, just call me a cab. I want to go down to my lawyer’s to put a codicil in my will.’ He died a month ago, when it was found that he had left all his money to the Society for Supplying Captains of London County Council steambeats with life-belts. When he had left me—it was all he ever did leave me—I called on Angelin—on the young lady whom I have mentioned.”

“And she?” I said.

“Told me the story again, bringing the total up to four hundred and sixty-seven. I will not dwell upon the scene. We parted for ever, and that evening I received back my letters. The presents she unaccountably forgot to return. And now, if you happen to be able to spare——”

I wished him good night, and went indoors.

1 Possibly the joke referred to:

I had a dream and was told that if I wished to go to Heaven, I must go up a certain flight of stairs and chalk my sins on each step I went up. I did so, and as I went up and found that the farther I went the more chalk I wanted. As I continued to go up I saw someone coming down, and discovered at last that it was the Doctor himself. So I said “Doctor, man, you are going the wrong way. You are going down instead of up. For what are you going down?” And the Doctor answered in a most lugubrious manner “More chalk!” (Evening Telegraph, January 9, 1901)

—Credited to Ian Maclaren, pseudonym of Rev. John Watson (1850–1907), a Scottish author and theologian.

—John Dawson

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums