Pearson’s Magazine (US), September 1905

IT had begun to snow. The policeman who was looking after Chinatown muttered an Irish oath which lost itself in his huge blonde moustache, and quickened his pace, wishing that he were off duty. Chinamen flitted to and fro in their furtive way, or stood gesticulating in groups at the corners. It was growing dusk.

The boy turned out of Pell Street in the aimless way common to those who are conscious of having many hours before them and no obvious means of passing them. He was a trim-built little fellow, but thinner than he should have been. That was because his meals were irregular, and not large even when he got them. A man in a shop had given him half a loaf that morning, which was a stroke of luck; but that had long since gone the way of all loaves. He was feeling hungry again now. That was why he lounged into Mott Street and stationed himself before the shop of Yen Lo. Somehow he never felt so hungry when he looked at the food in the window. Chinamen have quaint tastes in the matter of feeding. Yen Lo’s window was full of the gruesome carcasses of pigs. There were also certain fishes, pickled. Years had passed since they swam into the net. The smell of them was like the smell of the lion-house in Central Park, but more emphatic. The boy felt as he looked at them that there might be worse things than hunger.

A kick roused him from his reflections, not the powerful kick of an enemy, but the affectionate kick of a friend, the equivalent of a tap on the shoulder. He looked around to find the tall policeman towering over him.

“Well, sonny, what’s doin’?”

“Nothin’ doin’.”

“Go to that man I told you wanted an office boy?”

“Yep.”

“Wasn’t he wantin’ any of you?”

The boy shook his head mournfully. The tall policeman had been very good to him. Ever since they had struck up their queer friendship a month before, he had been fertile in suggestions for the boy’s advancement. Every time they met he had some new proposal which was to put him on the high road to fortune and a brownstone house on Fifth Avenue. Somebody was wanting an office boy, or perhaps a boy to run errands; a hotel needed a new bell-boy. There was no end to his well-meant suggestions. But nothing ever came of them. The places were always filled by the time the boy applied for them, and he was beginning to feel that he should never find one. He lived—somehow—from day to day. It had been difficult at first, when the death of his parents had flung him on his own resources, to wring a living out of the iron city. But he had managed it. The charity of the poor to one another is as wonderful in New York as in other big cities.

His history was of a common kind; he was English by birth, but his father, who had suffered from the popular superstition that America is a country where dollar bills grow on trees, had sold the small Devon farm to emigrate to the United States. He had found, like a great many others, that the United States did not particularly want him. And now he was dead, and his wife too; and the boy was alone.

The policeman strolled off, and the boy, having temporarily quelled his hunger by means of the scent of the pickled fish, moved on into the Bowery.

As he turned the corner he blundered into a man who was walking swiftly along the street, muffled in a huge overcoat.

“Now then, ye young devil,” said a deep voice not unkindly.

The man recovered his balance and was about to walk on, when he caught sight of the boy more distinctly and paused in astonishment. His costume was certainly not in keeping with the season. Winter and summer he wore nothing but a red shirt and a pair of very old breeches, though he sometimes, as at the present moment, added a still older pair of shoes to his equipment.

“Ye’re cold?” boomed the man from the depths of his great-coat.

The boy supposed, on reflection, that he was; but he had not noticed it particularly until now. He was used to his costume. But now that it was brought home to him by a direct question, he realized that his vague feeling of discomfort was due to that cause.

“Yep,” he said.

“Why don’t ye go home?”

“Haven’t got a home,” replied the boy shortly.

The man regarded him with a compassionate stare.

“Here,” he said.

He unbuttoned his coat, produced a coin from his pocket, and passed on at a swinging walk.

The boy examined the coin. It was a half-dollar. He stood looking at it, almost dazed. He had never handled specie in the bulk before.

As he stood there his eye was caught by something small and black on the ground. It was a pocket-book; and as he picked it up he saw that it was stuffed with greenbacks. As long as there had been anybody to do it, the boy had been well brought up, and remnants of what he had been taught remained with him. He had a rigid code of honesty, and not for a moment did it occur to him to appropriate this treasure that had apparently fallen from the skies for his own special benefit. He must find the big man in the overcoat and return the pocket-book. As a preliminary step, he would consult his friend the policeman. Meanwhile, being passing rich with half-a-dollar in his pocket, he would fill himself as full as one might for fifteen cents, and put by the remainder for the morrow.

Officer O’Gorman took charge of the pocket-book next morning, and commended the boy’s sagacity in entrusting it to an able and intelligent officer.

“Oi’ll take ut to the station,” he said, “and when we’ve found who it belongs to, ye climb in sharp, sonny, and get the reward. Why—”

He broke off with an exclamation of surprise. “Mike Mulroon!” he said. “Bedad, now if that’s not remarkable! Ye’re in luck, sonny. I was just goin’ to tell ye to scuttle to Mike Mulroon’s to ask for the “Boy Wanted” which he’s put on his door, an’ here ye’re introducin’ yerself to him without my knowin’ it. See, here’s his name in the pocket-book. Ye run ’round to his gymnasium, sonny, an’ give him the long green an’ tell him you’re the boy he’s been advertisin’ for. Ye know Mike’s gymnasium?”

The boy nodded. Mike Mulroon, toughest of middle-weight boxers in his day, which was now past, had set up a gymnasium on retiring from active work, and now devoted his time to teaching the noble art and training fighters for their battles. Every boy in the Bowery knew Mike by reputation, and secretly longed to follow in his footsteps. It was an unexampled piece of good luck that he should be able to present himself with such an excellent argument in his favor as the returned pocket-book, just when Mike was wanting a boy for his gymnasium. He started to run, but, recollecting that he was a monied man, stopped after he had reached the Bowery, and sprang on a car, where he had the perfect joy of putting the conductor to utter rout by presenting him with his fare. The conductor was a man who had little faith in human nature as represented by the youth of the Bowery, and he judged people by their exteriors. He thought the boy was stealing a ride, and said so.

“You had better be careful, me man,” said the boy haughtily, as he paid over the five cents.

Mulroon’s gymnasium was in Sixteenth Street. The boy charged in like a thunderbolt, to find the stalwart Michael engaged in sparring with a gilded youth who looked as if he had been in the habit of sitting up late.

The round came to an end, and Mike looked around.

“Well,” he said, “an’ what can I do for you?”

“Please, Mr. Mulroon,” said the boy rapidly, in the manner of one speaking a piece, “you dropped this last night when you gave me half-a-dollar and I picked it up, and Mr. O’Gorman says it’s got your name in it so it must be yours, so I’ve brought it and there ain’t any missing. And Mr. O’Gorman says you want a boy here, and will I do?”

“Bai Jove!” said the gilded youth, who had once spent a summer in London, and wished people to know it, “Bai Jove, smart boy that, really smart!” Mike Mulroon took the pocket-book in silence. The exhibition of honesty in one who was young enough to know worse had quite overpowered him.

“I’m much obliged to you,” he said at length.

“And can I be the boy wanted?”

“What can you do?”

“Anything.”

“Well, you can’t want more than that, Mulroon, eh?” said the gilded one, “and he’s honest, bai Jove. Here, kid, help me out of these bally pudding-cases, and I’ll give you a dollar.”

Thus did the boy enter upon his duties at Mike Mulroon’s gymnasium.

At first these were not extensive, nor was his pay; but both were greatly to his taste. He speedily fell into the ways of the gymnasium, and after a few weeks Mike began to feel that he could not get on without him. By the combination of an agile brain and a strict attention to business the boy made himself indispensable, and between Mike and himself there sprang up a friendship which was destined to last. Mike had all the Irishman’s fondness for children, and as for the boy he worshipped the ex-champion as only a boy can worship a man whose muscle has won him fame. There were scores of boys in the Bowery who would have boasted of it for weeks if the ex-champion of the middle-weight had spoken a couple of words to them. To be with him all day on the footing of an honored assistant was almost too much happiness.

In this way he passed the next four years of his life, drinking with his every breath the exhilarating atmosphere of the ring. It was small wonder that his ambitions were limited to the only profession of which he knew the ins and outs. He understood vaguely that there were in the world soldiers, and politicians, and artists, and that other boys had their eyes set on these professions as a goal; but for himself, his tastes lay in another direction. He wanted to be a fighting-man. There had been a feverish time, after a visit to Weber and Field’s theater, in the days before that famous partnership was dissolved, when he had wished to go on the stage. But learning from Mike that it was quite the fashionable thing for a first-class pugilist to take to the boards, his ambitions had veered around again to the ring, where they remained.

It was when he was sixteen, two years after his introduction to the gymnasium on Sixteenth Street, that his prospects of realizing his ambition began to grow brighter. Until then, greatly as he desired to do so, he had not been able to bring himself to ask Mike to take him in hand and educate his fists. He had to content himself with watching the tuition of others, and imitating the blows as best he could from memory.

But one day he arrived at the gymnasium in a state that commanded the attention even of the usually unobservant Mulroon. One of his eyes was closed, and his face wore a generally damaged expression.

“You’ve been fightin’, kid,” said Mike, proud of his penetration.

“Yes,” said the boy. During his two years at the gymnasium he had observed the speech of the gentlemen who came there, and had pruned his own of the little growth of dialect which had grown on him.

“Did ye win?”

“No.”

There was a pause.

“I can’t fight,” said the boy despairingly; “I don’t know how. Couldn’t you teach me, Mike?”

“Tache ye!” said Mike. “If ye’ve got it in yer, I’ll make a champeen of ye. But I’ll wait till ye’ve got two eyes to see by.”

And the boy retired, hugely delighted, to put raw steak on his injuries.

From this time his progress may be said to have been fairly steady and continuous. He was a pupil of the sort that Mike loved best, quick and active, willing to learn, and with no shadow of fear of punishment. From being “Boy Wanted,” he was promoted to the post of assistant instructor. When more than ordinarily enervated youths came to the gymnasium to be built up, preparatory to plunging once more into a whirl of cotillons and late suppers, they were turned over to the Kid, as more suited to their powers than the massive Mike. And occasionally when some fighter came to train with Mike for a battle, the Kid was allowed to act as one of the sparring-partners. So he acquired speed and knowledge, and learned by experience the difference that lies between the amateur and the professional.

It was two days after his eighteenth birthday that, arriving a little late at the gymnasium, he found Mike in conversation with a tall, wiry-looking young negro.

“Here, Kid,” said Mike, as he sighted him, “come here. Ye’ve read of Mr. Van Courtlandt’s unknown which is to fight Eddie Brock next month? This is the lad—only it’s a secret, so ye mustn’t tell—Joe Johnson, colored champeen of Brooklyn at the light-weight limit. Ye’ll be one of his sparrin’-partners.”

The Kid shook hands with the stranger. Being British-born, he had none of the American’s inherited dislike of the “coon,” but there was something in the Brooklyn man’s face which he did not fancy. His early life in the street had given him the habit of summing up the men he met at a glance.

Training work began that day, and with it a feud between the Kid and the colored man. In his first bout the former after being severely handled—for the Brooklyn champion was evidently not one of those boxers who play light in a training-bout—succeeded in planting a jab with his left on the mark, always a weak spot with negro fighters, which put an abrupt end to the encounter.

Johnson, as he rose to his feet again, shot a venomous glance at his antagonist. From that day onward every bout between the two was a pitched battle. Mike, unobservant as ever, did not notice any particular malice on the part of his man, but merely saw what he took to be a promising vigor. At the end of each day’s training the Kid ached as if he had been through a stiff fight in the roped ring. Incidentally he, too, began to train. It was evident to him that only fine condition could enable him to hold his own. Thus it came about that two men were getting into shape under Mike’s care.

And as events turned out, this was fortunate. This match between Eddie Brock and an unknown was one that was exciting considerable interest in sporting circles. Brock was a rising light-weight, and was supposed to have claims to the championship. This fight would decide his merit. Nothing remains secret for very long in New York, and it was generally understood, though unofficially, that the colored boxer, Johnson, was to be his opponent. Johnson was known to be a clever, resolute fighter, and it was thought that if Brock could obtain the decision over him, his backers would be justified in trying to arrange a match for him with Jimmy Garvis the Californian, the light-weight champion of America. A good deal of money would be won and lost over the present contest.

About a week before the fight, the Kid, walking home after his day’s work, met officer O’Gorman. Four years had had no effect on their friendship.

“An’ how is yer unknown?” inquired O’Gorman, after they had exchanged greetings.

“Oh, fine,” said the Kid. “Well inside the weight, and strong. He loosened a tooth for me to-day. Mike tells me not to give it away that the coon’s the man who’s to fight Brock; but, there, what’s the use? Everybody knows.”

Officer O’Gorman tapped him mysteriously on the chest and lowered his voice.

“An’ I’ll tell ye somethin’ which everybody doesn’t know,” he growled through his moustache.

The Kid looked interrogative.

“An’ that is that ’ere Joe Johnson won’t win,” said the policeman.

“Well, I’ve not seen Eddie fight, “said the Kid,” but he’ll have to be a warm proposition to put it over Johnson.”

“He’ll not win,” proceeded O’Gorman, “bekase he manes not to win.”

“What?”

The policeman nodded.

“Sure. We cops get next to the game easier than most. We hear things. There’s bin framing-propositions made to him. He’s bin paid to lose, an’ it’s up to him to do ut. He’s buncoed ye, Kid.”

“How do you know?” cried the Kid. “How did you hear?”

Officer O’Gorman displayed a coy reticence.

“Mustn’t tell pro-fessional secrets,” he said. “But you may stand on me. On the wor-rud of a mimber of the city police. So don’t ye go puttin’ yere long green on the wrong man, Kid,” he concluded, paternally.

The Kid was a man of action. He was early at the gymnasium next day. The colored representative of Brooklyn was alone in the room, punching the bag with bare fists in a meditative manner. He did not look up when the door opened.

The Kid came straight to the point. He was not fulsomely polite.

“You black beast!” he said, “so you’ve been playing double.”

The colored man’s reply was swift and direct. He wheeled around on the Kid, and his thick lips parted in a grin of rage. The next moment he sprang in like a flash with both arms working like flails.

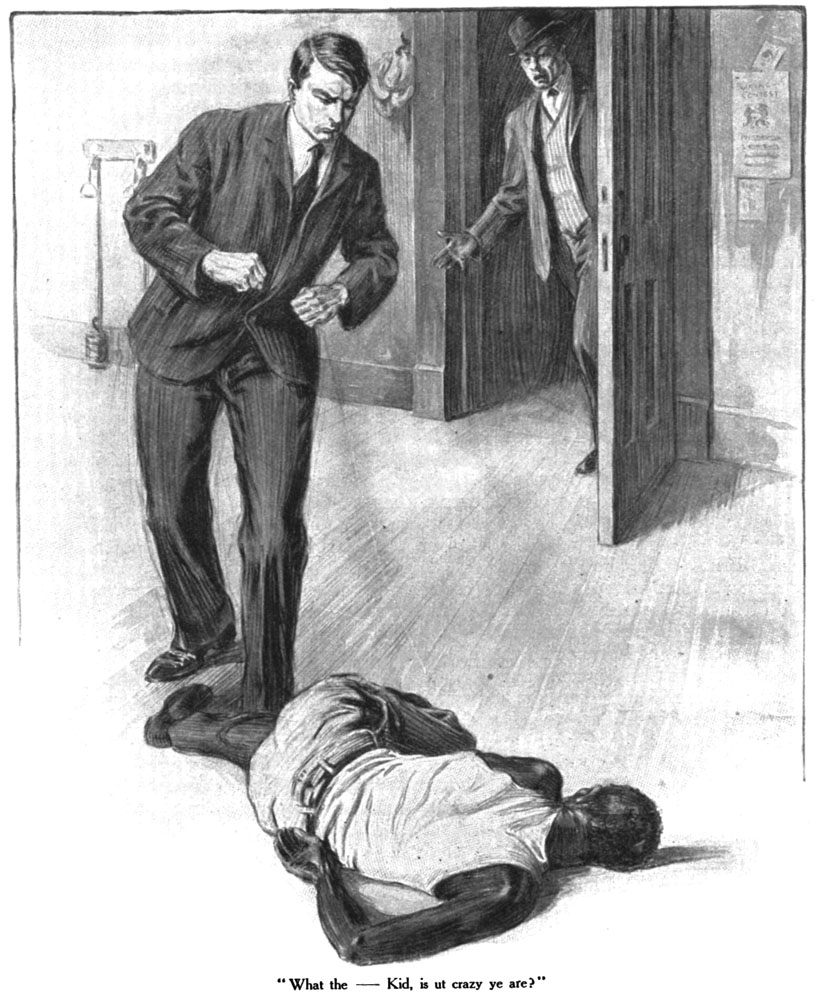

The Kid side-stepped to avoid the furious rush, and put in a left hook which brought his man up sharp. The black rushed again, landing heavily on the Kid’s ear. It was the last blow he delivered. As he came in to follow up his advantage, the Kid spied an opening. His right shot across, and Mike Mulroon, opening the door at that moment, was just in time to see the colored champion collapse in a heap like an empty sack.

“What the—Kid, is ut crazy ye are?”

The Kid wrenched himself free.

“Let me go, Mike,” he cried angrily.

“But what in the worruld do ye mane by knockin’ our man about just before his fight?”

“Yes, bai Jove,” said another voice, which the Kid remembered, “it certainly requires explanation. I’m Mr. Van Courtlandt, my lad. What do you mean by man-handling my nominee like this?”

The Kid faced him.

“You’ve been buncoed, sir,” he said excitedly. “Johnson never meant to win. He’s been got at. I was telling him that I knew, and he rushed at me.”

“And how do you know?”

For the first time the Kid realized that his evidence was, to say the least, thin.

But he had not to produce it. As he stood wondering how to begin, the prostrate negro suddenly rose and rushed through the door, banging it behind him. He had come to during the conversation and had remained where he lay, waiting for events to develop themselves. Apparently in his opinion they were not developing themselves satisfactorily, and he thought it best to quit a scene which promised neither profit nor pleasure.

Mr. Van Courtlandt stared after him blankly.

“There, sir!” said the Kid in triumph, “don’t that show it?”

“It does,” admitted Mr. Van Courtlandt pensively, “it does. But,” he added, “it does not show me how I am to find a boy who really will beat Master Eddie.”

“Try the Kid, son, try the Kid. Ye needn’t fear he’ll not do his best. An’ he’s as good a lad with his hands as ye’ll need to see.”

“Well,” said Mr. Van Courtlandt, “he was certainly good enough for the lamented Master Johnson. Then may I rely on your services?”

“Proud, sir,” said the Kid.

“An’ I’ll bet,” put in Mike, “six to four with any man in four-spot wafers that my Kid gets the decoration.”

And as was subsequently proved in fifteen rounds and part of a sixteenth, he could not have made a sounder investment.

(The next “Kid Brady—Light-Weight” story, “How he Broke his Training,” will appear in the November issue.)

Editors’ notes:

Pell Street, Mott Street: These names make it clear from the start that the Chinatown of the story is in New York City.

the way of all loaves: ironic variation on “the way of all flesh” as a euphemism for death (first cited from Westward Hoe [1607] by Webster and Dekker); here it means extinction via digestion.

specie: money in the form of coins

greenbacks: American paper money (United States Notes) printed in green on the reverse side, first issued as legal tender during the Civil War

bedad: a mild oath in Irish dialect, “by dad” as a euphemism for “by God”

middle-weight: weighing not over 160 pounds; although the weight classes are more finely divided now than then, the upper limit of the middleweight division has not changed since 1884.

speaking a piece: reciting a memorized passage

bai Jove: affected regional variant of “By Jove,” a mild oath

bally: British slang euphemism for ‘bloody’; confounded, dashed, blasted

pudding-cases: either the boxing gloves themselves or the protective cloth hand-wrappings beneath the gloves, from their resemblance to the cloth bag in which a pudding is boiled

Weber and Fields: Joe Weber (1867–1942) and Lew Fields (1867–1941), American vaudevillian “Dutch” (German-dialect) comics and longtime stage and business partners from youth. They opened the Weber and Fields Music Hall on Broadway in 1896; their partnership broke up in 1904.

pugilist to take to the boards: Notably, “Gentleman Jim” Corbett (1866–1933) had a successful show-business career after defeating John L. Sullivan for the heavyweight title in 1892, appearing on the vaudeville stage telling his own story, and acting in plays, comic sketches, and silent films. See this article for a broader history of boxers on stage.

enervated youths: From the activities listed, it seems that these weaklings had been worn out by the upper-class social whirl of dances and parties, and sought boxing training purely for the sake of fitness.

cotillons: in the American sense, formal balls at which debutantes are introduced to society; Wodehouse uses the original French spelling derived from a type of dance for four couples in a square (the classic origin from which American square-dancing was popularized). The American spelling is more often anglicized to ‘cotillion.’

on the mark: in boxing, a hit on the pit of the stomach, just beneath where the ribs divide, a sensitive spot due to the bundle of nerves called the solar plexus

light-weight: weighing no more than 135 pounds

manes: Irish-American dialect pronunciation of “means”

buncoed: American slang for swindled, cheated; OED has citations from the 1870s.

is ut crazy ye are?: Literally, “is it crazy you are?”: i.e., is it because you’re crazy that you’ve acted so?

long green; wafers: Slang for money. A 1903 article in The Booklovers Magazine defending slang lists as “current slang within the last five years: the coin, the scads, the long green, the dough, the dust, the shekels, the stamps, the beans, the wafers, the simoleons, the price, the spondulics, the needful, the tin, the collateral, cartwheels, plunks, balls (the last three limited, strictly, to dollars), the rocks, the stuff, the necessary, the boodle, and the ooks.” Wodehouse certainly picked up on several of these. To an Irish-American like Mulroon, the word ‘wafer’ probably brings to mind a Communion wafer, round and thin, so a money wafer is likely by this analogy to be a coin rather than a bill. David McGrann reminds us that ‘spot’ means ‘dollar’ in bills such as a five-spot or a ten-spot, and mentions the “Stella,” a $4 gold coin of 1879, though not many of these were minted. Still, it seems likely that the idea of a four-dollar coin is what is meant by a four-spot wafer (just as British bills quoted in guineas are not paid up in guinea coins), and that Mulroon is offering in essence to bet $24 against $16.

—Notes by Troy Gregory and Neil Midkiff

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums