The Saturday Evening Post, May 10, 1919

INASMUCH as the scene of this story is that historic pile, Belpher Castle, in the county of Hampshire, England, it would be an agreeable task to open it with a leisurely description of the place, followed by some notes on the history of the Earls of Marshmoreton who have owned it since the fifteenth century. Unfortunately, in these days of rush and hurry a novelist works at a disadvantage. He must leap into the middle of his tale with as little delay as he would employ in boarding a moving street car. He must get off the mark with the smooth swiftness of the Californian jack rabbit surprised while lunching. Otherwise, people throw him aside and go out to picture palaces.

I may briefly remark that the present Lord Marshmoreton is a widower of some forty-eight years; that he has two children—a son, Percy Wilbraham Marsh, Lord Belpher, who is on the brink of his twenty-first birthday, and a daughter, Lady Patricia Maud Marsh, who is just twenty; that the chatelaine of the castle is Lady Caroline Byng, Lord Marshmoreton’s sister, who married the very wealthy colliery owner, Clifford Byng, a few years before his death—which unkind people say she hastened; and that she has a stepson, Reginald. Give me time to mention these few facts and I am done. On the glorious past of the Marshmoretons I will not even touch.

Luckily the loss to literature is not irreparable. Lord Marshmoreton himself is engaged upon a history of the family, which will doubtless be on every bookshelf as soon as his lordship gets it finished. And as for the castle and its surroundings, including the model dairy and the amber drawing-room, you may see them for yourself any Thursday, when Belpher is thrown open to the public on payment of a fee of one shilling a head. The money is collected by Keggs, the butler, and goes to a worthy local charity. At least that is the idea; but the voice of calumny is never silent and there exists a school of thought, headed by Albert, the page boy, which holds that Keggs sticks to these shillings like glue and adds them to his already considerable savings in the Farmers and Merchants’ Bank on the left side of the High Street in Belpher village, next door to the Odd Fellows’ Hall.

With regard to this, one can only say that Keggs looks far too much like a particularly saintly bishop to indulge in any such practices. On the other hand, Albert knows Keggs. We must leave the matter open.

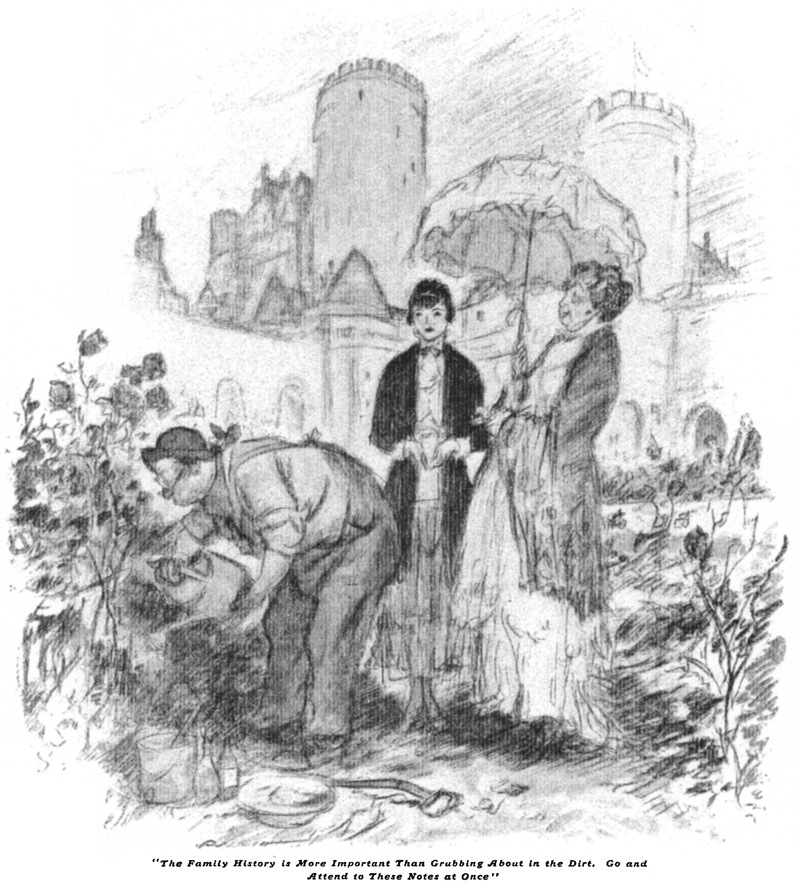

Of course appearances are deceptive. Anyone, for instance, who had been standing outside the front entrance of the castle at eleven o’clock on a certain June morning might easily have made a mistake. Such a person would probably have jumped to the conclusion that the middle-aged lady of a determined cast of countenance who was standing near the rose garden, talking to the gardener and watching the young couple strolling on the terrace below, was the mother of the pretty girl; and that she was smiling because the latter had recently become engaged to the tall, pleasant-faced youth at her side.

Sherlock Holmes himself might have been misled. One can hear him explaining the thing to Watson in one of those lightning flashes of inductive reasoning of his: “It is the only explanation, my dear Watson. If the lady were merely complimenting the gardener on his rose garden, and if her smile were merely caused by the excellent appearance of that rose garden, there would be an answering smile on the face of the gardener. But, as you see, he looks morose and gloomy.”

As a matter of fact the gardener—that is to say, the stocky, brown-faced man in shirt sleeves and corduroy trousers who was frowning into a can of whale-oil solution—was the Earl of Marshmoreton; and there were two reasons for his gloom: He hated to be interrupted while working, and, furthermore, Lady Caroline Byng always got on his nerves, and never more so than when, as now, she speculated on the possibility of a romance between her stepson Reggie and his lordship’s daughter Maud.

Only his intimates would have recognized in this curious corduroy-trousered figure the seventh Earl of Marshmoreton. The Lord Marshmoreton who made intermittent appearances in London, who lunched among bishops at the Athenæum Club without exciting remark, was a correctly dressed gentleman whom no one would have suspected of covering his sturdy legs in anything but the finest cloth. But if you will glance at your copy of Who’s Who and turn up the M’s, you will find in the space allotted to the Earl the words “Hobby—Gardening.” To which, in a burst of modest pride, his lordship has added “Awarded first prize for Hybrid Teas, Temple Flower Show, 1911.” The words tell their own story.

Lord Marshmoreton was the most enthusiastic amateur gardener in a land of enthusiastic amateur gardeners. He lived for his garden. The love which other men expend on their nearest and dearest, Lord Marshmoreton lavished on seeds, roses and loamy soil. The hatred which some of his order feel for socialists and demagogues, Lord Marshmoreton kept for rose slugs, rose beetles, and the small, yellowish-white insect which is so depraved and sinister a character that it goes through life with an alias, being sometimes called a rose hopper and sometimes a thrip. A simple soul, Lord Marshmoreton, mild and pleasant. Yet put him among the thrips and he became a dealer-out of death and slaughter, a destroyer of the class of Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan.

Thrips feed on the underside of rose leaves, sucking their juice and causing them to turn yellow; and Lord Marshmoreton’s views on these things were so rigid that he would have poured whale-oil solution on his grandmother if he had found her on the underside of one of his rose leaves sucking the juice.

The only time in the day when he ceased to be the horny-handed toiler and became the aristocrat was in the evening after dinner when, egged on by Lady Caroline, who gave him no rest in the matter, he would retire to his private study and work on his history of the family, assisted by his able secretary, Alice Faraday. His progress on that massive work was, however, slow. Ten hours in the open air make a man drowsy, and too often Lord Marshmoreton would fall asleep in mid-sentence, to the annoyance of Miss Faraday, who was a conscientious girl and liked to earn her salary.

The couple on the terrace had turned. Reggie Byng’s face as he bent over Maud was earnest and animated, and even from a distance it was possible to see how the girl’s eyes lit up at what he was saying. She was hanging on his words. Lady Caroline’s smile became more and more benevolent.

“They make a charming pair,” she murmured. “I wonder what dear Reggie is saying. Perhaps at this very moment ——”

She broke off with a sigh of content. She had had her troubles over this affair. Dear Reggie, usually so plastic in her hands, had displayed an unaccountable reluctance to offer his agreeable self to Maud, in spite of the fact that never, not even on the public platform which she adorned so well, had his stepmother reasoned more clearly than she did when pointing out to him the advantages of the match. It was not that Reggie disliked Maud. He admitted that she was a “topper,” on several occasions going so far as to describe her as “absolutely priceless.” But he seemed reluctant to ask her to marry him. How could Lady Caroline know that Reggie’s entire world—or such of it as was not occupied by racing cars and golf—was filled by Alice Faraday? Reggie had never told her. He had not even told Miss Faraday.

“—— perhaps at this very moment,” went on Lady Caroline, “the dear boy is proposing to her.”

Lord Marshmoreton grunted, and continued to peer with a questioning eye into the awesome brew which he had prepared for the thrips.

“One thing is very satisfactory,” said Lady Caroline. “I mean that Maud seems entirely to have got over that ridiculous infatuation of hers for that man she met in Wales last summer. She could not be so cheerful if she were still brooding on that. I hope you will admit now, John, that I was right in keeping her practically a prisoner here and never allowing her a chance of meeting the man again either by accident or design. They say absence makes the heart grow fonder. Stuff! A girl of Maud’s age falls in and out of love half a dozen times a year. I feel sure she has almost forgotten the man by now.”

“Eh?” said Lord Marshmoreton. His mind had been far away dealing with green flies.

“I was speaking about that man Maud met when she was staying with Brenda in Wales.”

“Oh, yes!”

“Oh, yes!” echoed Lady Caroline, annoyed. “Is that the only comment you can find to make? Your only daughter becomes infatuated with a perfect stranger, a man we have never seen, of whom we know nothing, not even his name—nothing except that he is an American and hasn’t a penny—Maud admitted that. And all you say is ‘Oh, yes!’ ”

“But it’s all over now, isn’t it? I understood the dashed affair was all over.”

“We hope so. But I should feel far safer if Maud were engaged to Reggie. I do think you might take the trouble to speak to Maud.”

“Speak to her? I do speak to her.” Lord Marshmoreton’s brain moved slowly when he was preoccupied with his roses. “We’re on excellent terms.”

Lady Caroline frowned impatiently. Hers was an alert, vigorous mind, bright and strong like a steel trap; and her brother’s vagueness and growing habit of inattention irritated her.

“I mean speak to her about becoming engaged to Reggie. You are her father. Surely you can at least try to persuade her.”

“Can’t coerce a girl!”

“I never suggested that you should coerce her, as you put it.

“I merely meant that you could point out to her, as a father, where her duty and happiness lie.”

“Drink this!” cried his lordship with sudden fury, spraying his can over the nearest bush, and addressing his remark to the invisible thrips. He had forgotten Lady Caroline completely. “Don’t stint yourselves! There’s lots more!”

A girl came down the steps of the castle and made her way toward them. She was a good-looking girl with an air of quiet efficiency about her. Her eyes were gray and whimsical. Her head was uncovered and the breeze stirred her dark hair. She made a graceful picture in the morning sunshine, and Reggie Byng, sighting her from the terrace, wabbled in his tracks, turned pink, and lost the thread of his remarks. The sudden appearance of Alice Faraday always affected him like that.

“I have copied out the notes you made last night, Lord Marshmoreton. I typed two copies.” Alice Faraday spoke in a quiet, respectful, yet subtly authoritative voice. She was a girl of great character. Previous employers of her services as secretary had found her a jewel. To Lord Marshmoreton she was rapidly becoming a perfect incubus. Their views on the relative importance of gardening and family histories did not coincide. To him the history of the Marshmoreton family was the occupation of the idle hour; she seemed to think that he ought to regard it as a life work. She was always coming and digging him out of the garden and dragging him back to what should have been a purely after-dinner task. It was Lord Marshmoreton’s habit when he awoke after one of his naps too late to resume work to throw out some vague promise of “attending to it to-morrow”; but, he reflected bitterly, the girl ought to have the tact and sense to understand that this was only polite persiflage and not to be taken literally.

“They are very rough,” continued Alice, addressing her conversation to the seat of his lordship’s corduroy trousers. Lord Marshmoreton always assumed a stooping attitude when he saw Miss Faraday approaching with papers in her hand; for he labored under a pathetic delusion, of which no amount of failures could rid him, that if she did not see his face she would withdraw. “You remember last night you promised you would attend to them this morning.”

She paused long enough to receive a noncommittal grunt by way of answer.

“Of course if you’re busy,” . . . she said placidly, with a half glance at Lady Caroline. That masterful woman could always be counted on as an ally in these little encounters.

“Nothing of the kind!” said Lady Caroline crisply. She was still ruffled by the lack of attention which her recent utterances had received, and welcomed the chance of administering discipline. “Get up at once, John, and go in and work.”

“I am working!” pleaded Lord Marshmoreton. Despite his forty-eight years his sister Caroline still had the power at times to make him feel like a small boy. She had been a great martinet in the days of their mutual nursery.

“The family history is more important than grubbing about in the dirt. I cannot understand why you do not leave this sort of thing to MacPherson. Why you should pay him liberal wages and then do his work for him I cannot see. You know the publishers are waiting for the history. Go and attend to these notes at once.”

“You promised you would attend to them this morning, Lord Marshmoreton,” said Alice invitingly.

Lord Marshmoreton clung to his can of whale-oil solution with the clutch of a drowning man. None knew better than he that these interviews, especially when Caroline was present to lend the weight of her dominating personality, always ended in the same way.

“Yes, yes, yes!” he said. “To-night, perhaps. After dinner, eh? Yes, after dinner. That will be capital.”

“I think you ought to attend to them this morning,” said Alice, gently persistent. It really perturbed this girl to feel that she was not doing work enough to merit her generous salary. And on the subject of the history of the Marshmoreton family she was an enthusiast. It had a glamour for her.

Lord Marshmoreton’s fingers relaxed their hold. Throughout the rose garden hundreds of spared thrips went on with their morning meal, unwitting of doom averted.

“Oh, all right, all right, all right. Come into the library.”

“Very well, Lord Marshmoreton.” Miss Faraday turned to Lady Caroline. “I have been looking up the trains, Lady Caroline. The best is the twelve-fifteen. It has a dining car, and stops at Belpher if signaled.”

“Are you going away, Caroline?” inquired Lord Marshmoreton hopefully.

“I am giving a short talk to the Social Progress League at Lewisham. I shall return to-morrow.”

“Oh!” said Lord Marshmoreton, hope fading from his voice.

“Thank you, Miss Faraday,” said Lady Caroline. “The twelve-fifteen.”

“The motor will be round at a quarter to twelve.”

“Thank you. Oh, by the way, Miss Faraday, will you call to Reggie as you pass and tell him I wish to speak to him.”

Maud had left Reggie by the time Alice Faraday reached him, and that ardent youth was sitting on a stone seat smoking a cigarette and entertaining himself with meditations in which thoughts of Alice competed for precedence with graver reflections connected with the subject of the correct stance for his approach shots. Reggie’s was a troubled spirit these days. He was in love, and he had developed a bad slice with his mid-iron. He was practically a soul in torment.

“Lady Caroline asked me to tell you that she wishes to speak to you, Mr. Byng.”

Reggie leaped from his seat.

“Hullo-ullo-ullo! There you are! I mean to say, what!”

He was conscious, as was his custom in her presence, of a warm, prickly sensation in the small of the back. Some kind of elephantiasis seemed to have attacked his hands and feet, swelling them to enormous proportions. He wished profoundly that he could get rid of his habit of yelping with nervous laughter whenever he encountered the girl of his dreams. It was calculated to give her a wrong impression of a chap—make her think him a fearful chump and what not!

“Lady Caroline is leaving by the twelve-fifteen.”

“That’s good! What I mean to say is—oh, she is, is she? I see what you mean.” The absolute necessity of saying something at least moderately coherent gripped him. He rallied his forces. “You wouldn’t care to come for a stroll, after I’ve seen the mater, or a row on the lake, or any rot like that, would you?”

“Thank you very much, but I must go in and help Lord Marshmoreton with his book.”

“What a rotten—I mean what a damn shame!” The pity of it tore at Reggie’s heartstrings. He burned with generous wrath against Lord Marshmoreton, that modern Simon Legree, who used his capitalistic power to make a slave of this girl and keep her toiling indoors when all the world was sunshine.

“Shall I go and ask him if you can’t put it off till after dinner?”

“Oh, no, thanks very much. I’m sure Lord Marshmoreton wouldn’t dream of it.”

She passed on with a pleasant smile. When he had recovered from the effect of this, Reggie proceeded slowly to the upper level to meet his stepmother.

“Hullo, mater! Pretty fit and so forth? What did you want to see me about?”

“Well, Reggie? What is the news?”

“Eh? What? News? Didn’t you get hold of a paper at breakfast? Nothing much in it. Tam Duggan beat Alec Fraser three up and two to play at Prestwick. I didn’t notice anything else much. There’s a new musical comedy at the Regal. An American piece. Opened last night and seems to be just like mother makes. The Morning Post gave it a topping notice. I must trickle up to town and see it some time this week.”

Lady Caroline frowned. This slowness in the uptake, coming so soon after her brother’s inattention, displeased her.

“No, no, no! I mean you and Maud have been talking to each other for quite a long time, and she seemed very interested in what you were saying. I hoped you might have some good news for me.”

Reggie’s face brightened. He caught her drift.

“Oh, ah, yes, I see what you mean. No, there wasn’t anything of that sort or shape or order.”

“What were you saying to her, then, that interested her so much?”

“I was explaining how I landed dead on the pin with my spoon out of a sand-trap at the eleventh hole yesterday. It certainly was a pretty ripe shot, considering. I’d sliced into this bally bunker, don’t you know—I simply can’t keep ’em straight with the iron nowadays—and there the pill was, grinning up at me from the sand. Of course, strictly speaking, I ought to have used a niblick, but ——”

“Do you mean to say, Reggie, that, with such an excellent opportunity, you did not ask Maud to marry you?”

“I see what you mean. Well, as a matter of absolute fact, I, as it were, didn’t!”

Lady Caroline uttered a wordless sound.

“By the way, mater,” said Reggie, “I forgot to tell you about that. It’s all off!”

“What!”

“Absolutely! You see, it appears there’s a chappie unknown for whom Maud has an absolute pash. It seems she met this sportsman up in Wales last summer. She was caught in the rain and he happened to be passing and rallied round with his raincoat, and one thing led to another. Always raining in Wales, what! Good fishing, though, here and there. Well, what I mean is, this cove was so deucedly civil, and all that, that now she won’t look at anybody else. He’s the blue-eyed boy, and everybody else is an also-ran with about as much chance as a blind man with one arm trying to get out of a bunker with a toothpick.”

“What perfect nonsense! I know all about that affair. It was just a passing fancy that never meant anything. Maud has got over that long ago.”

“She didn’t seem to think so.”

“Now, Reggie,” said Lady Caroline tensely, “please listen to me. You know that the castle will be full of people in a day or two for Percy’s coming-of-age, and this next few days may be your last chance of having a real, long, private talk with Maud. I shall be seriously annoyed if you neglect this opportunity. There is no excuse for the way you are behaving. Maud is a charming girl ——”

“Oh, absolutely! One of the best!”

“Very well, then!”

“But, mater, what I mean to say is ——”

“I don’t want any more temporizing, Reggie!”

“No, no! Absolutely not!” said Reggie dutifully, wishing he knew what the word meant, and wishing also that life had not become so frightfully complex.

“Now this afternoon, why should you not take Maud for a long ride in your car?”

Reggie grew more cheerful. At least he had an answer for that.

“Can’t be done, I’m afraid. I’ve got to motor into town to meet Percy. He’s arriving from Oxford this morning. I promised to meet him in town and tool him back in the car.”

“I see. Well, then, why couldn’t you ——”

“I say, mater, dear old soul,” said Reggie hastily, “I think you’d better tear yourself away and what not. If you’re catching the twelve-fifteen you ought to be staggering round to see you haven’t forgotten anything. There’s the car coming round now.”

“I wish now I had decided to go by a later train.”

“No, no, mustn’t miss the twelve-fifteen. Good, fruity train! Everybody speaks well of it. Well, see you anon, mater. I think you’d better run like a hare.”

“You will remember what I said?”

“Oh, absolutely!”

“Good-by, then. I shall be back to-morrow.”

Reggie returned slowly to his stone seat. He breathed a little heavily as he felt for his cigarette case. He felt like a hunted fawn.

Maud came out of the house as the car disappeared down the long avenue of elms. She crossed the terrace to where Reggie sat brooding on life and its problem.

“Reggie!”

Reggie turned.

“Hullo, Maud, dear old thing! Take a seat.”

Maud sat down beside him. There was a flush on her pretty face, and when she spoke her voice quivered with suppressed excitement.

“Reggie,” she said, laying a small hand on his arm, “we’re friends, aren’t we?”

Reggie patted her back paternally. There were few people he liked better than Maud.

“Always have been since the dear old days of childhood, what!”

“I can trust you, can’t I?”

“Absolutely!”

“There’s something I want you to do for me, Reggie. You’ll have to keep it a dead secret, of course.”

“The strong, silent man! That’s me! What is it?”

“You’re driving into town in your car this afternoon, aren’t you, to meet Percy?”

“That was the idea.”

“Could you go this morning instead, and take me?”

“Of course.”

Maud shook her head.

“You don’t know what you are letting yourself in for, Reggie, or I’m sure you wouldn’t agree so lightly. I’m not allowed to leave the castle, you know—because of what I was telling you about.”

“The chappie?”

“Yes. So there would be terrible scenes if anybody found out.”

“Never mind, dear old soul. I’ll risk it! None shall learn your secret from these lips!”

“You’re a darling, Reggie!”

“But what’s the idea? Why do you want to go to-day particularly?”

Maud looked over her shoulder.

“Because”—she lowered her voice, though there was no one near—“because he is back in London! He’s a sort of secretary, you know, to his uncle, and I saw in the paper this morning that the uncle returned yesterday after a long voyage in his yacht. So he must have come back too. He has to go everywhere his uncle goes.”

“And everywhere the uncle went the Chappie was sure to go!” murmured Reggie. “Sorry! Didn’t mean to interrupt!”

“I must see him. I haven’t seen him since last summer, nearly a whole year! And he hasn’t written to me, and I haven’t dared to write to him for fear of the letter going wrong. So, you see, I must go. To-day’s my only chance. Aunt Caroline has gone away. Father will be busy in the garden and won’t notice whether I’m here or not. And besides, to-morrow it will be too late because Percy will be here. He was more furious about the thing than anyone.”

“Rather the proud young aristocrat, Percy!” agreed Reggie. “I understand absolutely. Tell me just what you want me to do.”

“I want you to pick me up in the car about half a mile down the road. You can drop me somewhere in Piccadilly. That will be near enough to where I want to go. But the most important thing is about Percy. You must persuade him to stay and dine in town and come back here after dinner. Then I shall be able to get back by an afternoon train and no one will know I’ve been gone.”

“That’s simple enough, what! Consider it done. When do you want to start?”

“That’s simple enough, what! Consider it done. When do you want to start?”

“At once.”

“I’ll toddle round to the garage and fetch the car.” Reggie chuckled amusedly. “Rum thing! The mater’s just been telling me I ought to take you for a drive!”

“You are a darling, Reggie, really!”

Reggie gave her back another paternal pat.

“I know what it means to be in love, dear soul. I say, Maud, old thing, do you find love puts you off your stroke? What I mean is, does it make you slice your approach shots?”

Maud laughed.

“No. It hasn’t had any effect on my game so far. I went round in eighty-six the other day.”

Reggie sighed enviously.

“Women are wonderful!” he said. “Well, I’ll be legging it and fetching the car. When you’re ready, stroll along down the road and wait for me.”

When he had gone Maud pulled a small newspaper clipping from her pocket. She had extracted it from yesterday’s copy of the Morning Post’s society column. It contained only a few words:

Mr. Wilbur Raymond has returned to his residence at No. 11a Belgrave Square from a prolonged voyage in his yacht, the Siren.

Maud did not know Mr. Wilbur Raymond, and yet that paragraph had sent the blood tingling through every vein in her body. For as she had indicated to Reggie, when the Wilbur Raymonds of this world return to their town residences they bring with them their nephew and secretary, Geoffrey Raymond. And Geoffrey Raymond was the man Maud had loved ever since the day when she had met him in Wales.

II

THE sun that had shone so brightly on Belpher Castle at noon, when Maud and Reggie Byng set out on their journey, shone on the west end of London with equal pleasantness at two o’clock. In Little Gooch Street all the children of all the small shopkeepers, who support life in that backwater by selling each other vegetables and singing canaries, were out and about playing curious games of their own invention. Cats washed themselves on doorsteps preparatory to looking in for lunch at one of the numerous garbage cans which dotted the sidewalk. Waiters peered austerely from the windows of the two Italian restaurants which carry on the Lucretia Borgia tradition by means of one shilling and sixpenny table-d’hôte luncheons. The proprietor of the grocery store on the corner was bidding a silent farewell to a tomato which even he, though a dauntless optimist, had been compelled to recognize as having outlived its utility. On all these things the sun shone with a genial smile. Round the corner in Shaftesbury Avenue, an east wind was doing its best to pierce the hardened hides of the citizenry; but it did not penetrate into Little Gooch Street which, facing south and being narrow and sheltered, was enabled practically to bask.

Mac, the stout guardian of the stage door of the Regal Theater, whose gilded front entrance is on the avenue, emerged from the little glass case in which the management kept him and came out to observe life and its phenomena with an indulgent eye. Mac was feeling happy this morning. His job was a permanent one, not influenced by the success or failure of the productions which followed one another at the theater throughout the year; but he felt, nevertheless, a sort of proprietary interest in these ventures and was pleased when they secured the approval of the public. Last night’s opening, a musical piece by an American author and composer, had undoubtedly made a big hit, and Mac was glad because he liked what he had seen of the company and, in the brief time in which he had known him, had come to entertain a warm regard for George Bevan, the composer, who had traveled over from New York to help with the London production.

George Bevan turned the corner now, walking slowly and, it seemed to Mac, gloomily toward the stage door. He was a young man of about twenty-seven, tall and well-knit, with an agreeable, clean-cut face of which a pair of good and honest eyes were the most noticeable feature. His sensitive mouth was drawn down a little at the corners, and he looked tired.

“Morning, Mac.”

“Good morning, sir.”

“Anything for me?”

“Yes, sir, some telegrams. Oh, I’ll get ’em,” said Mac, as if reassuring some doubting friend and supporter as to his ability to carry through a labor of Hercules.

He disappeared into his glass case. George Bevan remained outside in the street surveying the frisking children with a somber glance. They seemed to him very noisy, very dirty and very young—disgustingly young. Theirs was joyous, exuberant youth which made a fellow feel at least sixty. Something was wrong with George to-day, for normally he was fond of children. Indeed, normally he was fond of most things. He was a good-natured and cheerful young man who liked life and the great majority of those who lived it contemporaneously with himself. He had no enemies and many friends.

But to-day he had noticed from the moment he had got out of bed that something was amiss with the world. Either he was in the grip of some divine discontent due to the highly developed condition of his soul, or else he had a grouch. One of the two. Or it might have been the reaction from the emotions of the previous night. On the morning after an opening your sensitive artist is always apt to feel as if he had been dried over a barrel.

Besides, last night there had been a supper party after the performance at the flat which the comedian of the troupe had rented in Jermyn Street, a forced, rowdy supper party where a number of tired people with overstrained nerves had seemed to feel it a duty to be artificially vivacious. It had lasted till four o’clock, when the morning papers with the notices arrived; and George had not got to bed till four-thirty. These things color the mental outlook.

Mac reappeared.

“Here you are, sir.”

“Thanks.”

George put the telegrams in his pocket. A cat, on its way back from lunch, paused beside him in order to use his leg as a serviette. George tickled it under the ear abstractedly. He was always courteous to cats, but to-day he went through the movements perfunctorily and without enthusiasm.

The cat moved on. Mac became conversational.

“They tell me the piece was a hit last night, sir.”

“It seemed to go very well.”

“My missus saw it from the gallery, and all the first-nighters was speaking very ’ighly of it. There’s a regular click, you know, sir, over here in London, that goes to all the first nights in the gallery. ’Ighly critical they are always. Specially if it’s an American piece like this one. If they don’t like it they precious soon let you know. My missus says they was all speakin’ very ’ighly of it. My missus says she ain’t seen a livelier show for a long time, and she’s a great theater-goer. My missus says they was all specially pleased with the music.”

“That’s good.”

“The Morning Leader give it a fine write-up. How was the rest of the papers?”

“Splendid, all of them. I haven’t seen the evening papers yet. I came out to get them.”

Mac looked down the street.

“There’ll be a rehearsal this afternoon, I suppose, sir? Here’s Miss Dore coming along.”

George followed his glance. A tall girl in a tailor-made suit of blue was coming toward them. Even at a distance one caught the genial personality of the new arrival. It seemed to go before her like a heartening breeze. She picked her way carefully through the children crawling on the sidewalk. She stopped for a moment and said something to one of them. The child grinned. Even the proprietor of the grocery store appeared to brighten up at the sight of her, as at the sight of some old friend.

“How’s business, Bill?” she called to him, as she passed the spot where he stood brooding on the mortality of tomatoes. And though he replied “Rotten!” a faint, grim smile did nevertheless flicker across his tragic mask.

Billie Dore, who was one of the chorus of George Bevan’s musical comedy, had an attractive face, a mouth that laughed readily, rather bright golden hair—which, she was fond of insisting with perfect truth, was genuine though appearances were against it—and steady blue eyes. The latter were frequently employed by her in quelling admirers who were encouraged by the former to become too ardent. Billie’s views on the opposite sex who forgot themselves were as rigid as those of Lord Marshmoreton concerning thrips. She liked men, and she would signify this liking in a practical manner by lunching and dining with them, but she was entirely self-supporting and when men overlooked that fact she reminded them of it in no uncertain voice, for she was a girl of ready speech and direct.

“ ’Morning, George. ’Morning, Mac. Any mail?”

“I’ll see, miss.”

“How did your better four-fifths like the show, Mac?”

“I was just telling Mr. Bevan, miss, that the missus said she ’adn’t seen a livelier show for a long time.”

“Fine. I knew I’d be a hit. Well, George, how’s the boy this bright afternoon?”

“Limp and pessimistic.”

“That comes of sitting up till four in the morning with festive hams.”

“You were up as late as I was, and you look like Little Eva after a night of sweet, childish slumber.”

“Yes, but I drank ginger ale and didn’t smoke eighteen cigars. And yet I don’t know. I think I must be getting old, George. All-night parties seem to have lost their charm. I was ready to quit at one o’clock, but it didn’t seem matey. I think I’ll marry a farmer and settle down.”

George was amazed. He had not expected to find his present view of life shared in this quarter.

“I was just thinking myself,” he said, feeling not for the first time how different Billie was from the majority of those with whom his profession brought him in contact, “how flat it all was. The show business, I mean, and these darned first nights, and the party after the show which you can’t sidestep. Something tells me I’m about through.”

Billie Dore nodded.

“Anybody with any sense is always about through with the show business. I know I am. If you think I’m wedded to my art let me tell you I’m going to get a divorce the first chance that comes along. It’s funny about the show business—the way one drifts into it and sticks, I mean. Take me, for example. Nature had it all doped out for me to be the belle of Hicks Corners. What I ought to have done was to buy a gingham bonnet and milk cows. But I would come to the great city and help brighten up the tired business man.”

“I didn’t know you were fond of the country, Billie.”

“Me? I wrote the words and music. Didn’t you know I was a country kid? My dad ran a Bide A Wee Home for flowers, and I used to know them all by their middle names. He was a nursery gardener out in Indiana. I tell you, when I see a rose nowadays, I shake its hand and say: ‘Well, well, Cyril, how’s everything with you? And how are Joe and Jack and Jimmy and all the rest of the boys at home?’ Do you know how I used to put in my time the first few nights I was over here in London? I used to hang round Covent Garden with my head back, sniffing. The boys that mess about with the flowers there used to stub their toes on me so often that they got to look on me as part of the scenery.”

“That’s where we ought to have been last night.”

“We’d have had a better time. Say, George, did you see the awful mistake on nature’s part that Babe Sinclair showed up with toward the middle of the proceedings? You must have noticed him, because he took up more room than any one man was entitled to. His name was Spenser Gray.”

George recalled having been introduced to a fat man of his own age who answered to that name.

“It’s a darned shame,” said Billie indignantly. “Babe is only a kid. This is the first show she’s been in. And I happen to know there’s an awfully nice boy over in New York crazy to marry her. And I’m certain this gink is giving her a raw deal. He tried to get hold of me about a week ago, but I turned him down hard; and I suppose he thinks Babe is easier. And it’s no good talking to her; she thinks he’s wonderful. That’s another kick I have against the show business. It seems to make girls such darned chumps! Well, I wonder how much longer Mr. Arbuckle is going to be retrieving my mail. What ho within there, Fatty?”

Mac came out, apologetic, carrying letters.

“Sorry, miss. By an oversight I put you among the G’s.”

“All’s well that ends well. ‘Put Me Among the G’s.’ There’s a good title for a song for you, George. Excuse me while I grapple with the correspondence. I’ll bet half of these are mash notes. I got three between the first and second acts last night. Why the nobility and gentry of this burg should think that I’m their affinity just because I’ve got golden hair—which is perfectly genuine, Mac, I can show you the pedigree—and because I earn an honest living singing off the key, is more than I can understand.”

Mac leaned his massive shoulders comfortably against the building and resumed his chat.

“I expect you’re feeling very ’appy to-day, sir?”

George pondered. He was certainly feeling better since he had seen Billie Dore, but he was far from being himself.

“I ought to be, I suppose, but I’m not.”

“Ah, you’re getting blarzy, sir, that’s what it is. You’ve ’ad too much of the fat, you ’ave. This piece was a big ’it in America, wasn’t it?”

“Yes. It ran over a year in New York, and there are three companies of it out now.”

“That’s ’ow it is, you see. You’ve gone and got blarzy. Too big a ’elping of success you’ve ’ad.” Mac wagged a head like a harvest moon. “You aren’t a married man, are you, sir?”

Billie Dore finished skimming through her mail, and crumpled the letters up into a large ball, which she handed to Mac.

“Here’s something for you to read in your spare moments, Mac. Glance through them any time you have a suspicion you may be a chump, and you’ll have the comfort of knowing that there are others. What were you saying about being married?”

“Mr. Bevan and I was ’aving a talk about ’im being blarzy, miss.”

“Are you blarzy, George?”

“So Mac says.”

“And why is he blarzy, miss?” demanded Mac rhetorically.

“Don’t ask me,” said Billie. “It’s not my fault.”

“It’s because, as I was saying, ’e’s ’ad too big a ’elping of success, and because ’e ain’t a married man. You did say you wasn’t a married man, didn’t you, sir?”

“I didn’t. But I’m not.”

“That’s ’ow it is, you see. You pretty soon gets sick of pulling off good things, if you ain’t got nobody to pat you on the back for doing of it. Why, when I was single, if I got ’old of a sure thing for the three-o’clock race and picked up a couple of quid, the thrill of it didn’t seem to linger somehow. But now, if some of the gentlemen that come ’ere put me onto something safe and I make a bit, ’arf the fascination of it is taking the stuff ’ome and rolling it onto the kitchen table and ’aving ’er pat me on the back.”

“How about when you lose?”

“I don’t tell ’er,” said Mac simply.

“You seem to understand the art of being happy, Mac.”

“It ain’t an art, sir. It’s just gettin’ ’old of the right little woman and ’aving a nice little ’ome of your own to go back to at night.”

“Mac,” said Billie admiringly, “you talk like a Tin Pan Alley song hit, except that you’ve left out the scent of honeysuckle and old Mister Moon climbing up over the trees. Well, you’re quite right. I’m all for the simple and domestic myself. If I could find the right man, and he didn’t see me coming and duck, I’d become one of the Mendelssohn’s March Daughters right away. Are you going, George? There’s a rehearsal at two-thirty for cuts.”

“I want to get the evening papers and send off a cable or two. See you later.”

“We shall meet at Philippi.”

Mac eyed George’s retreating back till he had turned the corner.

“A nice, pleasant gentleman, Mr. Bevan,” he said. “Too bad ’e’s got the pip the way ’e ’as, just after ’avin’ a big success like this ’ere. Comes of bein’ a artist, I suppose.”

Miss Dore dived into her vanity case and produced a puff, with which she proceeded to powder her nose.

“All composers are nuts, Mac. I was in a show once where the manager was panning the composer because there wasn’t a number in the score that had a tune to it. The poor geek admitted they weren’t very tuney, but said the thing about his music was that it had such a wonderful aroma. They all get that way. The jazz seems to go to their heads. George is all right though, and don’t let anyone tell you different.”

“Have you known him long, miss?”

“About five years. I was a stenographer in the house that published his songs when I first met him. And there’s another thing you’ve got to hand it to George for—he hasn’t let success give him a swelled head. The money that boy makes is sinful, Mac. He wears thousand-dollar bills next to his skin winter and summer. But he’s just the same as he was when I first knew him, when he was just hanging round Broadway looking out for a chance to be allowed to slip a couple of interpolated numbers into any old show that came along. Yes. Put it in your diary, Mac, and write it on your cuff, George Bevan’s all right. He’s an ace.”

Unconscious of these eulogies which, coming from one whose judgment he respected, might have cheered him up, George wandered down Shaftesbury Avenue, feeling more depressed than ever. The sun had gone in for the time being, and the east wind was frolicking round him like a playful puppy, patting him with a cold paw, nuzzling his ankles, bounding away and bounding back again, and behaving generally as east winds do when they discover a victim who has come out without his spring overcoat. It was plain to George now that the sun and the wind were a couple of confidence tricksters, working together as a team. The sun had disarmed him with specious promises and an air of cheery goodfellowship and had delivered him into the hands of the wind, which was now going through him with the swift thoroughness of the professional hold-up artist. He quickened his steps, and began to wonder if he was so sunk in senile decay as to have acquired a liver.

He discarded the theory as repellent. And yet there must be a reason for his depression. To-day of all days, as Mac had pointed out, he had everything to make him happy. Popular as he was in America, this was the first piece of his to be produced in London, and there was no doubt that it was a success of unusual dimensions. And yet he felt no elation.

He reached Piccadilly and turned westward. And then, as he passed the gates of the In and Out Club, he had a moment of clear vision and understood everything. He was depressed because he was bored, and he was bored because he was lonely. Mac, that solid thinker, had been right. The solution of the problem of life was to get hold of the right girl and have a home to go back to at night. He was mildly surprised that he had tried in any other direction for an explanation of his gloom. It was all the more inexplicable in that fully eighty per cent of the lyrics which he had set in the course of his career had had that thought at the back of them.

George gave himself up to an orgy of sentimentality. He seemed to be alone in the world which had paired itself off into a sort of seething welter of happy couples. Taxicabs full of happy couples rolled by every minute. Passing omnibuses creaked beneath the weight of happy couples. The very policeman across the street had just grinned at a flitting shopgirl, and she had smiled back at him. The only female in London who did not appear to be attached was a girl in brown who was coming along the sidewalk at a leisurely pace, looking about her in a manner that suggested that she found Piccadilly a new and stimulating spectacle.

As far as George could see she was an extremely pretty girl, small and dainty, with a proud little tilt to her head and the jaunty walk that spoke of perfect health. She was, in fact, precisely the sort of girl that George felt he could love with all the stored-up devotion of an old buffer of twenty-seven who had squandered none of his rich nature in foolish flirtations. He had just begun to weave a rose-tinted romance about their two selves, when a cold reaction set in. Even as he paused to watch the girl threading her way through the crowd, the east wind jabbed an icy finger down the back of his neck and the chill of it sobered him. After all, he reflected bitterly, this girl was only alone because she was on her way somewhere to meet some confounded man. Besides, there was no earthly chance of getting to know her. You can’t rush up to pretty girls in the street and tell them you are lonely. At least you can, but it doesn’t get you anywhere except the police station. George’s gloom deepened, a thing he would not have believed possible a moment before. He felt that he had been born too late. The restraints of modern civilization irked him. It was not, he told himself, like this in the good old days.

In the Middle Ages, for example, this girl would have been a damsel; and in that happy time practically everybody whose technical rating was that of damsel was in distress and only too willing to waive the formalities in return for services rendered by the casual passer-by. But the twentieth century is a prosaic age, when girls are merely girls and have no troubles at all. Were he to stop this girl in brown and assure her that his aid and comfort were at her disposal, she would undoubtedly call that large policeman from across the way, and the romance would begin and end within the space of thirty seconds or, if the policeman were a quick mover, rather less.

Better to dismiss dreams and return to the practical side of life by buying the evening papers from the shabby individual beside him who had just thrust an early edition in his face. After all, notices are notices—even when the heart is aching. George felt in his pocket for the necessary money, found emptiness, and remembered that he had left all his ready funds at his hotel.

It was just one of the things he might have expected on a day like this.

The man with the papers had the air of one whose business is conducted on purely cash principles. There was only one thing to be done, return to the hotel, retrieve his money, and try to forget the weight of the world and its cares in lunch. And from the hotel he could dispatch the two or three cables which he wanted to send to New York.

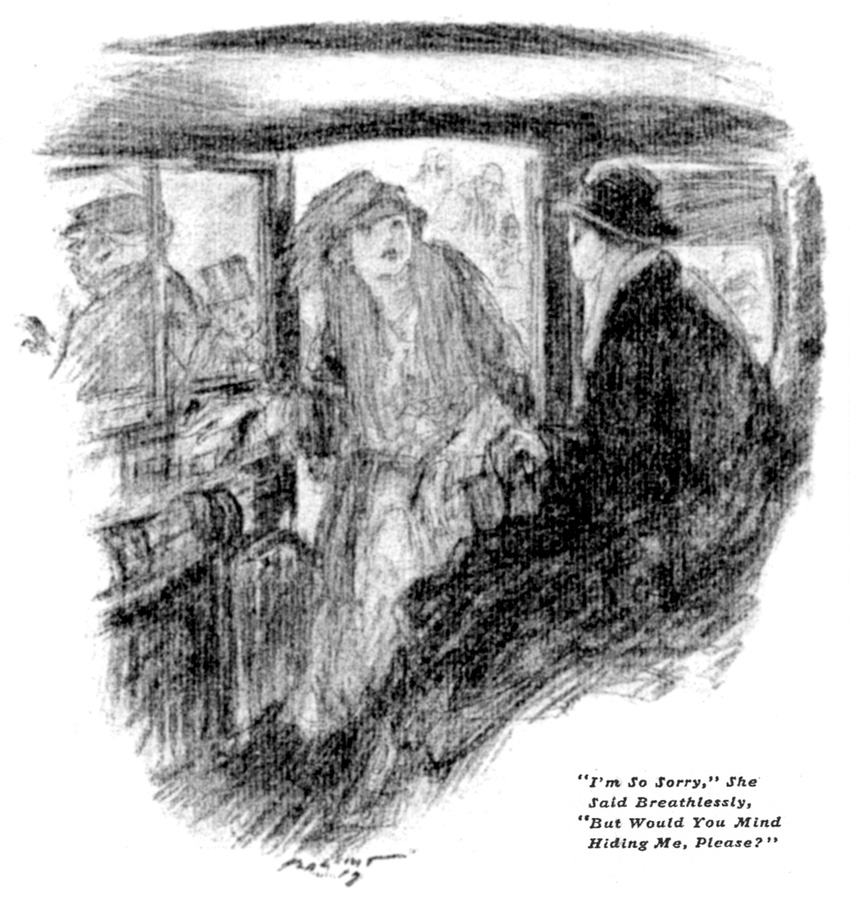

The girl in brown was quite close now, and George was enabled to get a clearer glimpse of her. She more than fulfilled the promise she had given at a distance. Had she been constructed to his own specifications, she could not have been more acceptable in George’s sight. And now she was going out of his life forever. With an overwhelming sense of pathos, for there is no pathos more bitter than that of parting from someone we have never met, George hailed a taxicab which crawled at the side of the road and, with all the refrains of all the sentimental song hits he had ever composed ringing in his ears, got in and passed away.

“A rotten world,” he mused, as the cab, after proceeding a couple of yards, came to a standstill in a block of the traffic. “A dull, flat bore of a world, in which nothing happens or ever will happen. Even when you take a cab, it just sticks and doesn’t move.”

At this point, the door of the cab opened and the girl in brown jumped in.

“I’m so sorry,” she said breathlessly, “but would you mind hiding me, please?”

(to be continued)

Note: Annotations to this story as it appeared in book form are on this site.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums