The Saturday Evening Post, August 21, 1915

HE CAME breezing up to me with Hicks Corners written all over him.

“Why, Miss Roxborough!”

“Why not?” I said.

“Don’t you remember me?”

I didn’t.

“My name is Ferris.”

He was probably right, but still the glad light of recognition kept out of my eyes. The name meant nothing in my young life.

“I was introduced to you last time I came here. We danced together.”

This seemed to bear the stamp of truth. If he was introduced to me, he probably danced with me. It’s what I’m at Geisenheimer’s for.

“When was that?” I asked.

“A year ago last April,” he said.

You’ve got to hand it to these rural charmers. They think that New York is folded up and put away in camphor when they leave, and not taken out again till they pay their next visit. The notion that anything could possibly have happened since he was last in our midst, to blur the memory of that happy evening, had not occurred to Mr. Ferris.

I suppose he was so accustomed to dating things from “when I was in New York” that he thought everybody else must do the same.

“Why, sure I remember you,” I said. “Algernon Clarence, isn’t it?”

“Not Algernon Clarence. My name’s Charlie.”

“My mistake. And what’s the big idea? Do you want to dance with me again?”

He did. So we went to it. Mine not to reason why, mine but to do and die, as the poem says. If an elephant had blown into Geisenheimer’s and asked me to dance I’d have had to do it. And I’m not saying that Mr. Ferris wasn’t the next thing to it. He was one of those earnest, persevering dancers—the kind that have taken twelve correspondence lessons.

I guess I was about due that night to meet someone from the country. There still come days in the spring when the country seems to get a strangle-hold on me and to start in pulling. I got up in the morning and looked out of the window, and the breeze just wrapped me round and began whispering about pigs and chickens. And when I went out on the Avenue, there seemed to be flowers everywhere. I headed for the Park, and there was the grass all green and the trees coming out, and a sort of something in the air. Why, if there hadn’t been a big cop keeping an eye on me I’d have flung myself down and bitten chunks out of the turf.

And the first tune they played when I got to Geisenheimer’s was the one that runs something like this:

I want to go back, I want to go back

To the place where I was born,

Far away from harm

With a milk-pail on my arm.

Why, Charlie from Squeedunk’s entrance couldn’t have been better worked up if he’d been a star in a Broadway show. The stage was just waiting for him.

But somebody’s always taking the joy out of life. I ought to have remembered that the most metropolitan thing in the metropolis is a rube who’s putting in a week there. We weren’t thinking on the same plane, Charlie and me. I wanted to talk about last season’s crops—the subject he fancied was this season’s chorus girls. I wanted to hear what the village patriarch said to the local constable about the hens—he wanted to hear what Georgie Cohan said to Willie Collier about the Lambs. Our souls didn’t touch by a mile and a half. Not that he cared.

“This is the life!” he said.

There’s always a point where this sort of man says that.

“I suppose you come here quite a lot.”

“Pretty often,” I said.

I didn’t tell him that I came there every night, and that I came because I was paid for it. If you’re a professional dancer at Geisenheimer’s you aren’t supposed to advertise the fact. The management has an idea that, if you did, it might send the public away thinking too hard when they had seen you win the Great Contest for the Lovely Silver Cup, which they offer later in the evening. And I guess they’re right, at that. That lovely silver cup’s a joke. I win it on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays; and Mabel Francis wins it on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. It’s all perfectly fair and square, of course. It’s purely a matter of merit who wins the lovely cup. Anybody could walk right into Geisenheimer’s and get it. Only somehow they don’t. And the coincidence that Mabel and I always happen to gather it in has kind of got on the management’s nerves, and they don’t like us to tell people we’re employed at the restaurant. They prefer us to blush unseen.

“It’s a great place,” said Mr. Ferris, “and New York’s a great place. I’d like to live all the time in New York.”

“The loss is ours. Why don’t you?”

“Some city! But dad’s dead now, and I’ve got the drug store, you know.”

He spoke as if I ought to remember reading about it in the papers.

“And I’m making good with it, what’s more. I’ve got push and ideas. I’m doing fine. Say, I got married since I saw you last.”

“You did, did you!” I said. “Then what are you doing, may I ask, cutting up on Broadway like a gay bachelor? I suppose you have left Friend Wife at Bodville Center, singing ‘Where is my wandering boy to-night?’ ”

“Not Bodville Center; Ashley, Maine. That’s where I live. My wife comes from Rodney. Pardon me, I’m afraid I stepped on your foot.”

“My fault. I lost step. Well, aren’t you ashamed even to think of your wife, when you’ve left her all alone out there, while you come whooping it up in New York? Haven’t you any conscience?”

“But I haven’t left her. She’s here.”

“In New York?”

“In this restaurant. She’s up there.”

I looked up at the balcony. There was a face hanging over the red-plush rail. I had noticed it before when we were dancing round. I had wondered why she was looking so sorry for herself. Now I began to see.

“Why aren’t you dancing with her and giving her a good time, then?” I said.

“Oh, she’s having a good time.”

“She doesn’t look it. She looks as if she would like to be down here dancing.”

“She doesn’t dance much.”

“Don’t you have dances at Ashley?”

“It’s different at home. She dances well enough for Ashley, but—well, this isn’t Ashley.”

“I see. But you’re not like that.”

He gave a kind of smirk.

“Oh, I’ve been in New York before.”

I could have slapped his wrist, the sawed-off little rube! He made me mad. He was ashamed to dance in public with his wife, didn’t think her good enough for him. So he had dumped her in a chair, fed her a lemonade, and then sashayed off to give himself a tall time. They could have had me pinched for what I was thinking just then.

The band started again.

“This is the life,” said Mr. Ferris. “Come along!”

“Let somebody else do it,” I said. “I’m tired. I’ll introduce you to some friends of mine.”

So I took him off, and wished him on to some girls I knew at one of the tables.

“Shake hands with my friend Vernon Castle,” I said. “He wants to show you the latest steps. He does most of them on your feet.”

“This is the life!” said Charlie.

And I left him and headed for the balcony.

She was leaning with her elbows on the red plush, looking down at the dancing-floor. They had just started another tune, and hubby was moving round with one of the girls I’d introduced him to.

She didn’t have to prove to me that she came from the country. I knew it. She was a little bit of a thing, old-fashioned looking. She was dressed in gray, with white muslin collar and cuffs, and her hair done simple under a black hat.

I kind of hovered for a while. As a general thing I’m more or less there with the nerve, but somehow I sort of hesitated to butt in. I guess it was because she looked so sorry for herself. Then I took a brace on myself and made for the vacant chair.

“I’ll sit here, if you don’t mind,” I said.

I could see she was wondering who I was and what right I had horning in, but wasn’t certain whether it might not be Broadway etiquette for strangers to come and sit down and start chatting.

“I’ve just been dancing with your husband,” I said to ease things along.

“I saw you.”

She gave me a look with her big brown eyes, and it was only the thought that the management might not like it that prevented me picking up something large and heavy and dropping it over the rail on to hubby. That was how I felt about Mr. Ferris just then. The poor kid was doing everything with those eyes except cry, and it didn’t look as if she could keep off that for long. She looked like a dog that’s been kicked and can’t understand why.

She looked away and began to fiddle with the string of the electric light. There was a hatpin on the table. She picked it up and dug at the red plush.

“Ah, come on, sis,” I said, “tell me all about it.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Quit your kidding. You can’t fool me. Tell me your troubles.”

“I don’t know you.”

“You don’t have to know a person to tell her your troubles. I sometimes tell mine to the cat that camps out on the wall opposite my room. What did you want to leave the country for, with the summer just coming on?”

She didn’t answer, but I could see it coming, so I sat still and waited. And presently she seemed to make up her mind that, even if it was no business of mine, it would be a relief to talk about it.

“We’re on our honeymoon. Charlie wanted to come to New York. I didn’t want to, but he was set on it. He has been here before.”

“So he told me.”

“He’s crazy about New York.”

“But you’re not?”

“I hate it.”

“What’s your kick?”

She dug away at the red plush with the hatpin, picking out little bits and dropping them over the edge. I could see she was bracing herself to put me wise to the whole trouble. There’s a time comes, when things aren’t going right and you’ve had all you can stand, when you’ve got to tell somebody about it, no matter who it is.

“I hate New York,” she said, getting it out with a rush at last. “I’m scared of it. It—it isn’t fair, Charlie bringing me here. I didn’t want to come. I knew what would happen. I felt it all along.”

“What do you reckon will happen, then?”

She must have picked away an inch of the red plush before she answered. It was lucky that Jimmy, the balcony waiter, didn’t see her. It would have broken his heart. He’s as proud of that red plush as if he had paid for it himself.

“When I first went to Rodney,” she said, “two years ago—we moved there from Illinois—and began to get to know people, I found there was a man there named Tyson, Jack Tyson, who lived all alone and didn’t seem to want to know anybody. I couldn’t understand it, till someone told me all about him. I can understand it now. Jack Tyson married a Rodney girl, and they came to the city for their honeymoon, just like us. And when they got there I guess she got to comparing him with the fellows she saw and comparing the city with Rodney, and when she got home she just couldn’t settle down.”

“Well?”

“After they had been back in Rodney for a little while she ran away—back to the city, I guess.”

“And he got a divorce, I suppose?”

“No.”

“He didn’t?”

“He still thinks she may come back to him.”

“Still thinks she may come back? After three years?”

“Yes. He keeps her things just the same as she left them—everything the same as when she went away.”

“But isn’t he sore at her for what she did? If I was a man and a girl treated me that way I’d be apt to swing on her, if she tried to show up again.”

“He wouldn’t. Nor would I, if—if anything like that happened to me. I’d wait and wait, and go on hoping all the time. And I’d go down to the depot every afternoon to meet the train, just like Jack Tyson.”

Something splashed on the tablecloth. It made me jump.

“For the love of Mike!” I said. “What’s the trouble? Brace up! I know it’s a sad story, but it’s not your funeral.”

“It is. It is. The same thing’s going to happen to me.”

“Take a hold on yourself. Don’t cry like that!”

“I can’t help it. Oh, I knew it would happen. It’s happening right now. Look—look at him!”

I glanced over the rail, and I saw what she meant. There was her Charlie, cutting up all over the floor as if he had just discovered that he hadn’t lived till then. I saw him say something to the girl he was dancing with. I wasn’t near enough to hear him, but I bet it was “This is the life!” If I had been his wife and in the same position as this kid, I guess I’d have felt as bad as she did, for if ever a man exhibited all the symptoms of incurable Newyorkitis, it was this Charlie Ferris.

“I’m not like these New York girls,” she choked. “I’m not smart. I don’t want to be. I just want to live at home and be quiet and happy. I knew it would happen if we came to the city. He looks down on me. He doesn’t think me good enough for him.”

“Stop it! Pull yourself together!”

“And I do love him so.”

Goodness knows what I should have said if I could have thought of anything to say. Seeing someone really up against it simply makes a dummy of me, as if somebody had turned off my ideas with a tap. But just then the music stopped, and somebody on the floor below began to speak.

“Ladeez ’n’ gemmen! There will now take place our great num-bah contest. This gen-u-ine sporting contest. . . .”

It was Izzy Baermann, doing his nightly spiel, introducing the lovely silver cup; and it meant that, for me, duty called. From where I was sitting I could see Izzy looking anxiously about the room, and I knew that he was looking for me. It’s the management’s nightmare that one of these evenings Mabel or I won’t show up and some stranger will get away with the lovely cup. It doesn’t cost above ten dollars, that cup, but they would hate to have it go out of the family.

“Sorry I’ve got to go,” I said. “I have to be in this.”

And then suddenly I had the great idea. It came to me like a flash. I looked at her, and I looked over the rail at Charlie, the Debonair Pride of Ashley, and I knew that this was where I got a cinch on my place in the Hall of Fame, along with the great thinkers of the age.

I took her by the shoulder and shook her—shook her good.

“Come on!” I said. “Stop crying and powder your nose, and get a move on. You’re going to dance this.”

She looked up at me as if I had suggested that she should jump off the Brooklyn Bridge.

“But I couldn’t!”

“You’re going to!”

“But Charlie doesn’t want to dance with me.”

“It may have escaped your notice, but your Charlie is not the only man here. I’m going to dance with Charlie myself, and I’ll introduce you to someone who can go through the movements. Listen!”

“The lady of each competing couple”—this was Izzy, getting it off his diaphragm—“will receive a ticket containing a num-bah. The dance will then proceed, and the num-bahs will be eliminated one by one, those called out by the judge kindly returning to their seats as their num-bah is called. The num-bah finally remaining is the winning num-bah. This contest is a genuine sporting contest decided purely by the skill of the holders of the various num-bahs, as judged upon by the competent judge appointed by the management.” Izzy stopped blushing at the age of six. “Will ladies now kindly step forward and receive their num-bahs? The winner, the holder of the num-bah left on the floor when the other num-bahs have been eliminated”—I could see Izzy getting more and more uneasy, wondering where on earth I’d got to—“will receive this love-r-ly silver cup, presented by the management. Ladies will now kindly step forward and receive their num-bahs!” I turned to the kid.

“There,” I said, “wouldn’t you like to win a love-r-ly silver cup?”

“But I couldn’t.”

“You never know your luck.”

“But it isn’t luck. Didn’t you hear him say? It’s a contest decided purely by skill.”

“Well, try your skill then. For the love of Mike,” I said, “show a little pep. Exhibit some ginger. You aren’t a quitter, are you? Aren’t you ready to stir a finger to keep your Charlie? I thought you had more sand. Suppose you win, think what it will mean. He will look up to you for the rest of your life. When he starts yawping about New York all you will have to say is ‘New York? Ah, yes, that was the town where I won the love-r-ly silver cup, was it not?’ And he’ll drop as if you had hit him behind the ear with a sand-bag. Can’t you see that this is your chance to get the ball and chain on him for the term of his natural life? Pull yourself together and try!”

Well, the girl had sand, after all. I saw those brown eyes of hers flash.

“I’ll try,” she said after a second.

“Good for you! Now get those tears dried off and fix yourself up, and I’ll go down and get the tickets.”

Izzy was mighty relieved when I bore down on him.

“Gee!” he said. “You got my goat! I thought you was sick or something. Here’s your ticket!”

“I want two, Izzy. One’s for a friend of mine. And say, Izzy, I’d take it as a personal favor if you could square the competent judge appointed by the management to let her stop on the floor as one of the last two couples. There’s a reason. She’s a kid from the country, and she wants to make a hit.”

“Sure,” said Izzy, “that’ll be all right. Here are the tickets.” He lowered his voice. “Yours is thirty-six, hers is ten. Don’t forget and go mixing them up!”

I went back to the balcony. On the way I got hold of Charlie.

“We’re dancing this together,” I said. He grinned all across his face. I could hear him saying to himself: “Am I a hit? I guess not!”

I found Mrs. Charlie looking as if she had never shed a tear in her life. She certainly had pluck, that kid. Her eyes were shining, and she was bursting to get action.

“Come along!” I said. “Stick to your ticket like glue and watch your step!”

I guess you have seen these sporting contests at Geisenheimer’s. Or, if you haven’t seen them at Geisenheimer’s, you’ve probably seen them some place else. They’re all the same.

When we began the floor was crowded so that there was hardly standing room. Don’t tell me there aren’t any optimists nowadays! Why, everyone was looking as if they were the guys who had put the trot in fox-trot and was wondering whether to have the cup in the parlor or the bedroom. You never saw such a happy, hopeful crowd in your life.

Presently Izzy gave tongue. The management expects him to pull some comedy stuff on these occasions, so he did his best.

“Num-bahs seven, eleven, and twenty-one will kindly rejoin their sorrowing friends.”

That gave us a little more elbowroom, and the band started again.

I want to go back, I want to go back,

I want to go back to the farm,

Far away from harm,

With a milk-pail on my arm.

I miss the rooster,

The one that useter

Wake me up at four a. m.

I think your great big city’s

Very pretty.

But nevertheless I want to be there. . . .

“Num-bahs thirteen, sixteen and seventeen, good-by!” Off we went again.

I was born in Michigan,

And I wish and wish again

That I was back

In the town where I was born. . . .

“Num-bah twelve, we hate to part with you, but—back to your table!”

A plump dame in a red hat, who had been dancing with a kind smile as if she were doing it to amuse the children, left the floor.

“Num-bahs six, fifteen and twenty, thumbs down!”

And pretty soon the only couples left were Charlie and me, Mrs. Charlie and the fellow I’d introduced her to, and a bald-headed man and a girl in a white hat. He was one of your stick-at-it performers. He had been dancing all the evening. I had noticed him from the balcony. From up there he looked like a hard-boiled egg.

He was a trier all right, that guy, and had things been otherwise than what they were, so to speak, I’d have been glad to see him win. But it was not to be. Ah, no!

“Num-bah nineteen, you’re getting all flushed. Take a rest!”

So there it was, a straight sporting contest between me and Charlie, and Mrs. Charlie and her man. Every nerve in my system was trembling with excitement, was it not? It was not.

Charlie hadn’t a suspicion of the state of the drama. As I’ve already hinted, he wasn’t a dancer who took much of his attention off his feet while in action. He was there to do his durnedest, not to inspect objects of interest by the wayside. The correspondence college he had graduated from doesn’t guarantee to teach you to do two things at once when it mails you your diploma.

He was breathing heavily down my neck, with eyes glued to the floor. All he knew was that the sporting contest had thinned out some, and the honor of Ashley, Maine, was in his hands.

You know how the public begins to sit up and take notice when these dance contests have been narrowed down to two couples. There are evenings when I quite forget myself, when I’m one of the last two left in, and get all excited.

There’s a sort of hum in the air, and as you go round the room people at the tables start applauding. Why, if you weren’t wise to the inner workings of the thing you’d be all of a twitter.

It didn’t take my practiced ear long to get next to the fact that it wasn’t me and Charlie that the great public was rooting for. We would go round the floor without getting a hand, and every time Mrs. Charlie and her guy got to a corner there was a noise like election night.

I took a look at her across the floor, and I didn’t wonder that she was making a hit. Say, she was a different kid. I never saw anyone look so happy and pleased with herself. Her eyes were like lamps, and her cheeks all pink, and she was going to it like a champion. I knew what had made the hit with the people. It was the look of her. She made you think of fresh milk and new-laid eggs and birds singing. Just to take a slant at her was like getting away to the country in August. It’s funny about guys who live all the time in the city. They chuck out their chests, and talk about little old New York being good enough for them, and there’s a street in heaven they call Broadway, and all the rest of it, but it seems to me that what they really live for is the three weeks in the summer when they get away into the country. I knew exactly why they were rooting so hard for Mrs. Charlie. She made them think of their vacation which was coming along, when they would go and board at the farm, and drink out of the old oaken bucket, and call the cows by their first names.

Gee! I felt like that myself. All day the country had been tugging at me, and now it tugged worse than ever.

I could have smelled the new-mown hay if it hadn’t been that when you’re at Geisenheimer’s you have to smell Geisenheimer’s and nothing else, because it leaves no chance for competition.

“ ’At-a-boy!” I breathed into Charlie’s ear. “Keep-a-working. It looks to me as if we were going back in the betting.”

“Uh-huh!” he grunted, too busy to blink.

“Pull some of those fancy steps of yours. We need them in our business.”

And the way that boy worked—it was a sin!

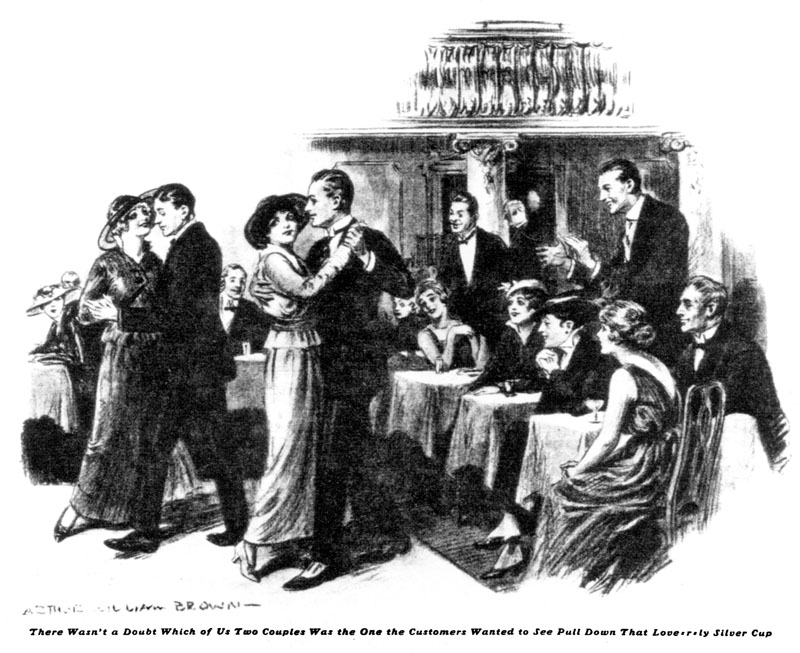

Out of the corner of my eye I could see Izzy Baermann, and he wasn’t looking happy. He was nerving himself for one of those quick referee’s decisions—the sort you make and then duck under the ropes and run five miles to avoid the incensed populace. It was this sort of thing happening now and again that prevented Izzy’s job, otherwise one of the world’s softest, from being the perfect cinch. Mabel Francis told me that one night, when Izzy declared her the winner of the great sporting contest, it was such raw work that she thought there’d have been a riot. It looked pretty much as if he was afraid the same thing was going to happen now. There wasn’t a doubt which of us two couples was the one the customers wanted to see pull down that love-r-ly silver cup. It was a walk-over for Mrs. Charlie, and Charlie and I were simply among those present.

But Izzy had his duty to do, and drew a pay envelope for doing it, so he moistened his lips, looked round to see that his strategic railroads weren’t blocked, swallowed twice, pulled at his collar, and said in a husky voice:

“Num-bah ten, please re-tiah!”

I stopped at once.

“Come along,” I said to Charlie. “That’s our exit cue.”

And we walked off the floor, amidst applause.

“Well,” says Charlie, taking out his handkerchief and attending to his brow, which was like the village blacksmith’s, “we didn’t do so bad, did we? We didn’t do so bad, I guess! We——”

And he looks up at the balcony, expecting to see the dear little wife draped over it with that worshiping look in her eyes, adoring him. And just as his eye is moving up, it gets caught by the sight of her a whole heap lower down than he had expected—on the floor, in fact, behaving like Mrs. Castle and the Dolly Sisters rolled into one.

She wasn’t doing much in the worshiping line just then. She was too busy.

It was a regular triumphal procession for the kid. She couldn’t have felt much more popular if she had been Queen of Coney at the Mardi Gras. She and her partner were doing one or two rounds now for exhibition purposes, like the winning couple always does at Geisenheimer’s, and the room was fairly rising at them. You’d have thought from the way they clapped that they had been betting all their spare cash on her.

Charlie gets her well focused, then he lets his jaw drop till it pretty near bumped against the floor.

“But—but—but——” he began.

“I know,” I said. “It begins to look as if she could dance well enough for the city after all. It begins to look as if she had sort of put one over on somebody, don’t it! It begins to look as if it were a pity you didn’t think of dancing with her yourself.”

“I—I—I——”

“You come along and have a nice cold drink,” I said, “and you’ll soon pick up.”

He tottered after me to a table, looking as if he had been hit by a street car. He had got his.

I was so busy looking after Charlie, flapping the towel and working on him with the oxygen, that, if you’ll believe me, it wasn’t for quite a time that I thought of glancing round and finding out how the thing had struck Izzy Baermann.

If you can imagine a fond and trusting father whose only son has swung on him with a brick, jumped on his stomach, and then gone South with all his money, you have a pretty good notion of how poor Izzy looked. He was staring at me across the room and talking to himself and jerking his hands about. Whether he thought he was talking to me or whether he was rehearsing the scene where he broke it to the boss that a mere stranger had got away with his love-r-ly silver cup, I don’t know. Whichever it was, he was being mighty eloquent.

I gave him a nod, as much as to say that it would all come right in the future, and then I turned to Charlie again. He was beginning to pick up.

“She won the cup!” he said in a dazed voice, looking at me as if he expected me to do something about it.

“You bet she did!”

“But—but—well, what do you know about that!”

I saw the moment had come to put it straight to him.

“I’ll tell you what I know about it,” I said. “If you take my advice you’ll hustle that kid straight back to Ashley, or wherever it is that you poison the natives by making up the wrong prescriptions, before she gets New York into her system so deep that you can’t get it out. Otherwise you’re in for trouble. When I was talking to her upstairs she was telling me about a fellow in her village who got it in the neck just the same as you’re apt to do.”

He started.

“She was telling you about Jack Tyson?”

“That was his name. It seems he lost his wife by letting her have too much Broadway. Say, don’t you think it’s funny she should have mentioned him, if she hadn’t had some notion that she might act the same way his wife did?”

He turned quite green.

“You don’t think she would do that!”

“Well, if you had heard her! She couldn’t talk of anything except this Tyson and what his wife did to him. She spoke of it sort of sad, kind of regretful, as if she was sorry but felt that it had to be. I could see she had been thinking about it a whole lot.”

Charlie stiffened in his seat, and then began to melt with pure fright. He held up his empty glass with a shaking hand and took a long drink out of it. It didn’t take much observation to see that he had had the jolt he wanted and was going to be quite a lot less jaunty and metropolitan from now on. In fact, the way he looked, I suspected that he was through with metropolitan jauntiness for the rest of his life.

“I’ll take her home to-morrow,” he said. “But—will she come?”

“That’s up to you. If you get real smooth and persuasive, maybe. . . . Here she is now. I should get busy at once.”

Mrs. Charlie, carrying the cup, came to the table. I was wondering what would be the first thing she would say. If it had been Charlie in the same position, of course he would have said “This is the life!” but I looked for something snappier from her. If I had been in her place there were at least ten things I could have thought of to say, each nastier than the other.

She sat down and put the cup on the table. Then she gave the cup a long look. Then she drew a deep breath. Then she looked at Charlie.

“Oh, Charlie dear,” she said, “I do wish I had been dancing with you!”

Well, I’m not sure, but I guess that that must have stung about as much as any of the things I would have said.

Charlie got right off the mark. After what I had told him he wasn’t wasting any time.

“Darling,” he said humbly, “you’re a wonder. What will they say about this at home!”

He did pause here for a moment, for it took nerve to say it; but then he went right on.

“Mary, how would it be if we went home right away—first train to-morrow—and showed the folks the cup?”

“Oh, Charlie!” she said.

His face lit up as if someone had pulled a switch.

“You will? You don’t want to stop on? You aren’t crazy about New York?”

“If there was a train I’d start to-night. But I thought you loved the city so, Charlie?”

He gave a sort of shiver.

“I never want to see it again in my life!” he said.

“You’ll excuse me,” I said, getting up. “I think there’s a friend of mine wants to speak to me.”

And I crossed the room to where Izzy had been standing for the last five minutes, making signals to me with his eyebrows.

You couldn’t have called Izzy coherent at first. He certainly had trouble with his vocal cords, poor fellow! There was one of those African explorer men used to come to Geisenheimer’s a lot when he was home from roaming the trackless desert, and he used to tell me about tribes he’d met, who didn’t use real words at all but talked to one another in clicks and gurgles. He pulled some of their chatter one night to amuse me and, believe me, Izzy Baermann was talking the same language now. Only he wasn’t doing it to amuse me.

He was like one of those talking machines when it’s getting into its stride.

“Be calm, Isadore,” I said. “Something is troubling you. Tell me all about it!”

He clicked some more, and then he got it out.

“Are you crazy?”

“I’m not. Why do you ask?”

“What did you do it for? Didn’t I tell you as plain as I could, didn’t I tell you twenty times, when you came for the tickets, that yours was thirty-six?”

“Didn’t you say my friend’s was thirty-six?”

“Are you deaf? I said hers was ten.”

“Then,” I said handsomely, “say no more. The mistake was mine. It begins to look as if I must have got them mixed.”

He did a few Swedish exercises.

“Say no more? That’s good! That’s great! That’s the best I’ve heard! You’ve got the nerve! I will say that.”

“It was a lucky mistake of mine, Izzy. It saved your life. These guys would have lynched you if you had given me the cup instead of her. They were solid for her all right.”

“Never mind about that. What’s the boss going to say when I tell him?”

“Forget the boss! Haven’t you any romance in your system, Izzy? Look at those two, sitting there with their heads together. Isn’t it worth a silver cup to have made them happy for life? They are on their honeymoon, Izzy. Tell the boss exactly what happened, and say that I thought it was up to Geisenheimer’s to give them a wedding present.”

He clicked for a spell.

“Ah!” he said. “Ah! Now you’ve said it! Now you’ve given yourself away! You did it on purpose. You meant to mix those tickets. I thought as much. Say, who do you think you are, getting fresh that way? Don’t you know that professional dancers are three for ten cents? I could go right out now and whistle and get a dozen girls for your job. Just one minute after I tell the boss what you’ve done you’ll find yourself fired.”

“No, I shan’t, Izzy, because I’m going to resign.”

“You’d better!”

“That’s what I think. I’m sick of this joint, Izzy. I’m sick of dancing. I’m sick of Broadway. I’m sick of everything. I’m going back to the country while the going is good. I thought I had got gingham and sunbonnets clear out of my system, but I hadn’t. You can write this out and stick it up over your shaving mirror, Izzy, because it’s true: Once a rube, always a rube. I’ve suspected it for a long, long time, and to-night I know it. Tell the boss that I’m sorry, but it had to be done. And if he wants to talk back, he’ll have to do it by mail. Mrs. John Tyson, General Delivery, Rodney, Maine, is the address.”

Compare the British version of this story.

Thanks to Neil Midkiff for providing the transcription and images for this story.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums