The Saturday Evening Post, June 8, 1918

YOU know, the longer I live in New York, the more clearly I see that half the trouble in this bally world is caused by the light-hearted and thoughtless way in which chappies dash off letters of introduction and hand them to other chappies to deliver to chappies of the third part. It’s one of those things that make you wish you were living in the Stone Age. What I mean to say is: If a fellow in those days wanted to give anyone a letter of introduction he had to spend a month or so carving it on a large sized bowlder; and the chances were that the other chappie got so sick of lugging the thing round in the hot sun that he dropped it after the first mile. But nowadays it’s so easy to write letters of introduction that everybody does it without a second thought, with the result that some perfectly harmless cove like myself gets into the soup. The last time that happened to me was when the chump, Cyril Bassington-Bassington, came over with a letter from my Aunt Agatha.

This chump, Bassington-Bassington, would seem from contemporary accounts to have blown in one morning at seven-forty-five. He was given the respectful raspberry by my man, Jeeves, and told to try again about three hours later, when there would be a sporting chance of my having sprung from my bed with a glad cry to welcome another day, and all that sort of thing. Which was rather decent of Jeeves, by the way; for it so happened that there was a slight estrangement, a touch of coldness—a bit of a row, in other words—between us at the moment because of some rather priceless purple socks, which I was wearing against his wishes; and a lesser man might easily have snatched at the chance of getting back at me a bit by loosing Cyril into my bedchamber at a moment when I couldn’t have stood a two-minute conversation with my dearest pal.

You know how it is. The fierce rush of modern life; the cheery supper party; the wine when it is red—and so forth. . . . Well, what I mean to say is, as far as I’m concerned, what with one thing and another, the old bean is a trifle slow at getting into its stride in the morning; and until I have had my early cup of tea and brooded on life for a bit, absolutely undisturbed, I’m not much of a lad for the merry chitchat.

So Jeeves very sportingly shot Cyril out into the crisp morning air and didn’t let me know of his existence until he brought his card in with my tea.

“And what might all this be, Jeeves?” I said, giving the thing the glassy gaze.

“The gentleman called to see you earlier in the day, sir.”

“Good Lord, Jeeves! You don’t mean to say the day starts earlier than this?”

“He desired me to say he would return later, sir.”

“I’ve never heard of him. Have you ever heard of him, Jeeves?”

“I am familiar with the name Bassington-Bassington, sir. There are three branches of the Bassington-Bassington family—the Shropshire Bassington-Bassingtons, the Hampshire Bassington-Bassingtons, and the Kent Bassington-Bassingtons.”

“England seems pretty well stocked up with them.”

“Tolerably so, sir.”

“No chance of a sudden shortage, I mean—what?”

“Presumably not, sir,”

“And what sort of a specimen is this one?”

“I could not say, sir, on such short acquaintance.”

“Will you give me a sporting two to one, Jeeves, judging from what you have seen of him, that this chappie is not a blighter or an excrescence?”

“No, sir. I should not care to venture such odds.”

“I knew it. Well, the only thing that remains to be discovered is what kind of a blighter he is.”

“Time will tell, sir! The gentleman brought this letter for you, sir.”

“What ho! What ho! What ho! I say, Jeeves; this is from my Aunt Agatha!”

“Indeed, sir?”

I gave the thing the rapid eye. The wassail bowl, which had flowed overnight with a fairly steady gush into the small hours, had left me rather pessimistic that morning; and the moment I saw Aunt Agatha’s handwriting something seemed to tell me that Fate was about to let me have it in the lower ribs once again. It’s a rummy thing.

Aunt Agatha is the one person in the world I daren’t offend, and it always happens that everyone she sends to me with letters of introduction gets into trouble of some sort. And she always seems to think that I ought to have watched over them while they were in New York like a blend of nursemaid and guardian angel. Which, of course, is a bit thick. There was only one gleam of comfort.

“He isn’t going to stay in New York long, Jeeves. He’s headed for Washington. Going to give the chappies there the up-and-down before taking a whirl at the diplomatic service. So he ought to be leaving us eftsoon or right speedily, thank goodness! I should say a lunch and a couple of dinners would about meet the case—what?”

“I fancy that would be entirely adequate, sir.”

He started to put out my things and there was an awkward sort of silence.

“Not those socks, Jeeves,” I said, gulping a bit, but having a dash at the careless offhand sort of tone. “Give me the purple ones.”

“I beg your pardon, sir?” said Jeeves coldly.

“Those jolly purple ones.”

“Very good, sir.”

He lugged them out of the drawer as if he were a vegetarian fishing a caterpillar out of his salad. You could see he was feeling deeply. Deuced painful and all that, this sort of thing; but a chappie has got to assert himself every now and then if he doesn’t want his valet to treat him as an absolute serf. Absolutely!

I was looking for Cyril to show up again any time after breakfast, but he didn’t appear; so, toward one o’clock I trickled out to the club, where I had a date to feed the Wooster face with a pal of mine of the name of Caffyn—George Caffyn, a fellow who writes plays, and what not. He was a bit late, but bobbed up finally, saying that he had been kept at a rehearsal of his new piece, Ask Dad; and we started in. We had just reached the coffee when the waiter came up and said that Jeeves wanted to see me.

Jeeves was in the waiting room. He gave the socks one pained look as I came in; then averted his eyes.

“Mr. Bassington-Bassington has just telephoned, sir.”

“Why interrupt my lunch to tell me that, Jeeves? It means little or nothing in my young life.”

“He was somewhat insistent that I should inform you at the earliest possible moment, sir, as he has been arrested and would be glad if you could step round and bail him out.”

“Arrested!”

“Yes, sir.”

“What for?”

“He did not favor me with his confidence, sir.”

“This is a bit thick, Jeeves.”

“Precisely, sir.”

“I suppose I had better totter round—what?”

“That might be the judicious course, sir.”

So I collected Old George, who very decently volunteered to stagger along with me, and we hopped into a taxi. We sat round at the police station for a bit on a wooden bench in a sort of anteroom, and presently a policeman appeared, leading in Cyril.

“Hullo! Hullo! Hullo!” I said. “What?”

My experience is that a fellow never really looks his best just after he’s come out of a cell. When I was up at Oxford I used to have a regular job bailing out a pal of mine who never failed to get pinched every boat-race night; and he always looked like something that had been dug up by the roots.

Cyril was in pretty much the same sort of shape. He had a black eye and a torn collar, and altogether was nothing to write home about—especially if one was writing to Aunt Agatha. He was a thin, tall chappie, with a lot of light hair and pale blue goggly eyes, which made him look like one of the rarer kinds of fish. He had just that expression of peeved surprise that one of those sheepshead fish in Florida has when you haul it over the side of the boat.

“I got your message,” I said.

“Oh, are you Bertie Wooster?”

“Absolutely! And this is my pal, George Caffyn. Writes plays, and what not, don’t you know!”

We all shook hands; and the policeman, having retrieved a piece of chewing gum from the under side of a chair, where he had parked it against a rainy day, went off into a corner and began to contemplate the infinite.

“This is a rotten country!” said Cyril.

“Oh, I don’t know, you know, don’t you know!” I said.

“We do our best,” said George.

“Old George is an American,” I explained. “Writes plays, don’t you know, and what not.”

“Of course I didn’t invent the country,” said George. “That was Columbus. But I shall be delighted to consider any improvements you may suggest and lay them before the proper authorities.”

“Well, why don’t the policemen in New York dress properly?”

George took a look at the chewing officer across the room.

“I don’t see anything missing,” he said.

“I mean to say, why don’t they wear helmets, like they do in London? Why do they look like postmen? It isn’t fair on a fellow! Makes it dashed confusing. I was simply standing on the pavement, looking at things, when a fellow who looked like a postman prodded me in the ribs with a club. I didn’t see why I should have postmen prodding me. Why the dickens should a fellow come three thousand miles to be prodded by postmen?”

“The point is well taken,” said George. “What did you do?”

“I gave him a shove, you know. I’ve got a frightfully hasty temper, you know. All the Bassington-Bassingtons have got frightfully hasty tempers, don’t you know!”

“One of these days the clan will go hurting somebody.”

“And then he biffed me in the eye and lugged me off to this beastly place.”

“I’ll fix it, old son,” I said.

And I hauled out the bank roll and went off to open negotiations, leaving Cyril to talk to George. I don’t mind admitting that I was a bit perturbed. There were furrows in the old brow and I had a kind of foreboding feeling. So long as this chump stayed in New York I was sort of responsible for him, and he didn’t give me the impression of being the species of cove a reasonable chappie would care to be responsible for for more than about three minutes.

I mused with a considerable amount of tensity over Cyril that night when I got home and Jeeves had brought me the final highball. I couldn’t help feeling that this visit of his to America was going to be one of those times that try men’s souls, and what not. I hauled out Aunt Agatha’s letter of introduction and reread it; and there was no getting away from the fact that she undoubtedly appeared to be somewhat wrapped up in this blighter, and considered it my mission in life to shield him from harm while on the premises.

I was deuced thankful that he had taken such a liking for George Caffyn, Old George being a steady sort of cove. After I had got him out of his dungeon cell, he and Old George had gone off together, as chummy as brothers, to watch the afternoon rehearsal of Ask Dad.

There was some talk, I gathered, of their dining together. I felt pretty easy in my mind while George had his eye on him.

I had got about as far as this in my meditation when Jeeves came in with a telegram. At least, it wasn’t a telegram; it was a cable—from Aunt Agatha. And this is what it said:

Has Cyril Bassington Bassington called yet On no account introduce him into theatrical circles Vitally important Letter follows

I read it a couple of times.

“This is rummy, Jeeves!”

“Yes, sir?”

“Very rummy and dashed disturbing!”

“Will there be anything further to-night, sir?”

Of course, if he was going to be as bally unsympathetic as that, there was nothing to be done. My idea had been to show him the cable and ask his advice. But if he was letting those purple socks rankle to that extent the good old noblesse oblige of the Woosters couldn’t lower itself to the extent of pleading with the man. Absolutely not! So I gave it a miss.

“Nothing more, thanks.”

“Good night, sir.”

“Good night.”

He floated away and I sat down to think the thing over. I had been directing the best efforts of the old bean to the problem for a matter of half an hour when there was a ring at the bell.

I went to the door, and there was Cyril, looking pretty festive.

“I’ll come in for a bit if I may,” he said. “Got something rather priceless to tell you.” He curvetted past me into the sitting room, and when I got there after shutting the front door I found him reading Aunt Agatha’s cable and giggling in a rummy sort of manner. “Oughtn’t to have looked at this, I suppose. Caught sight of my name and read it without thinking. I say, Wooster, old friend of my youth, this is rather funny. Do you mind if I have a drink? Thanks awfully, and all that sort of rot. Yes; it’s rather funny, considering what I came to tell you. Jolly Old Caffyn has given me a small part in that musical comedy of his, Ask Dad. Only a bit, you know; but quite tolerably ripe. I’m feeling frightfully braced, don’t you know!”

He drank his drink and went on. He didn’t seem to notice that I wasn’t jumping about the room, yapping with joy.

“You know—I’ve always wanted to go on the stage, you know,” he said; “but my jolly old guv’nor wouldn’t stick it at any price; put the old Waukeesi down with a bang and turned bright purple whenever the subject was mentioned. That’s the real reason why I came over here, if you want to know. I knew there wasn’t a chance of my being able to work this stage wheeze in London without somebody getting on to it and tipping off the guv’nor; so I sprang the scheme of popping over to Washington to broaden my mind. There’s nobody to interfere on this side, you see; so I can go right ahead.”

I tried to reason with the poor chump.

“But your guv’nor will have to know, sometime.”

“That’ll be right. I shall be the jolly old star by then and he won’t have a leg to stand on.”

“It seems to me he’ll have one leg to stand on while he kicks me with the other.”

“Why, where do you come in? What have you got to do with it?”

“I introduced you to George Caffyn.”

“So you did, old top; so you did. I’d quite forgotten. I ought to have thanked you before. Well, so long! There’s an early rehearsal of Ask Dad to-morrow morning and I must be toddling.

“Rummy the thing should be called Ask Dad, when that’s just what I’m not going to do. See what I mean—what? Well, pip-pip!”

“Toodle-oo!” I said sadly, and the blighter scudded off. I dived for the phone and called up George Caffyn.

“I say, George, what’s all this about Cyril Bassington-Bassington?”

“What about him?”

“He tells me you’ve given him a part in your show.”

“Oh, yes; just a few lines.”

“But I’ve just had fifty-seven cables from home telling me on no account to let him go on the stage!”

“I’m sorry. But Cyril is just the type I need for that part. He’s simply got to be himself.”

“It’s pretty tough on me, George, old man. My Aunt Agatha sent this blighter over with a letter of introduction to me and she will hold me responsible.”

“She’ll cut you out of her will?”

“It isn’t a question of money. But—of course you’ve never met my Aunt Agatha; so it’s rather hard to explain. But she’s a sort of human vampire bat, and she’ll make things most fearfully unpleasant for me when I go back to England. She’s the kind of woman who comes and rags you before breakfast, don’t you know!”

“Well, don’t go back to England, then. Stick round and become President.”

“But, George, old top——”

“Good night!”

“But, I say, George, old man!”

“You didn’t get my last remark. It was Good night! You idle rich may not need any sleep, but I’ve got to be bright and fresh in the morning. God bless you!”

I felt as if I hadn’t a friend in the world. I was so jolly well worked up that I went and banged on Jeeves’ door. It wasn’t a thing I’d have cared to do, as a rule; but it seemed to me that now was the time for all good men to come to the aid of the party, so to speak, and that it was up to Jeeves to rally round the young master, even if it broke up his beauty sleep.

Jeeves emerged in a brown dressing gown.

“Sir?”

“Deuced sorry to wake you up, Jeeves, and what not; but all sorts of dashed disturbing things have been happening.”

“I was not asleep. It is my practice, on retiring, to read a few pages of some instructive book.”

“That’s good! What I mean to say is: If you’ve just finished exercising the old bean it’s probably in midseason form for tackling problems. Jeeves, Mr. Bassington-Bassington is going on the stage!”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Ah! The thing doesn’t hit you! You don’t get it properly! Here’s the point: All his family are most fearfully dead against his going on the stage. There’s going to be no end of trouble if he isn’t headed off. And, what’s worse, my Aunt Agatha will blame me, you see! And you know what she is!”

“Very much so, sir.”

“Well, can’t you think of some way of stopping him?”

“Not, I confess, at the moment, sir.”

“Well, have a stab at it.”

“I will give the matter my best consideration, sir. Will there be anything further to-night?”

“I hope not! I’ve had all I can stand already.”

“Very good, sir.”

He popped off.

The part Old George had written for the chump, Cyril, took up about two pages of type script; but it might have been Hamlet, the way that poor misguided pinhead worked himself to the bone over it. I suppose that if I heard him his lines once I did it a dozen times in the first couple of days. He seemed to think that my only feeling about the whole affair was one of enthusiastic admiration, and that he could rely on my support and sympathy.

What with trying to imagine how Aunt Agatha was going to take this thing, and being wakened up out of the dreamless in the small hours every other night to give my opinion of some new bit of business Cyril had invented, I became more or less the good old shadow. And all the time Jeeves was still pretty cold and distant about the purple socks. It’s this sort of thing that ages a chappie, don’t you know, and makes his youthful joie de vivre go a bit groggy at the knees.

In the middle of it Aunt Agatha’s letter arrived. It took her about six pages to do justice to Cyril’s father’s feelings in regard to his going on the stage, and about six more to give me a kind of sketch of what she would say, think and do if I didn’t keep him clear of injurious influences while he was in America.

The letter came by the afternoon mail and left me with a pretty firm conviction that it wasn’t a thing I ought to keep to myself. I didn’t even wait to ring the bell; I whizzed for the kitchen, bleating for Jeeves, and butted into the middle of a regular tea party of sorts. Seated at the table were a depressed-looking cove, who might have been a valet or something, and a boy in a Norfolk suit. The valet chappie was drinking a highball, and the boy was being tolerably rough with some jam and cake.

“Oh, I say, Jeeves!” I said. “Sorry to interrupt the feast of reason and flow of soul, and so forth, but——”

At this juncture the small boy’s eye hit me like a bullet and stopped me in my tracks. It was one of those cold, clammy, accusing sort of eyes—the kind that make you reach up to see if your tie is straight; and he looked at me as if I were some sort of unnecessary product Cuthbert the Cat had brought in after a ramble among the local ash cans. He was a stoutish infant, with a lot of freckles and a good deal of jam on his face.

“Hullo! Hullo! Hullo!” I said. “What?”

There didn’t seem much else to say.

The stripling stared at me in a nasty sort of way through the jam. He may have loved me at first sight; but the impression he gave me was that he didn’t think a lot of me and wasn’t betting much that I would improve a great deal on acquaintance. I had a kind of feeling that I was about as popular with him as a cold Welsh rabbit.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

“My name? Oh—Wooster, don’t you know, and what not.”

“My pop’s richer than you are!”

That seemed to be all about me. The child, having said his say, started in on the jam again. I turned to Jeeves.

“I say, Jeeves, can you spare a moment? I want to show you something.”

“Very good, sir.”

We toddled into the sitting room.

“Who is your little friend, Sidney the Sunbeam, Jeeves?”

“The young gentleman, sir?”

“It’s a loose way of describing him; but I know what you mean.”

“I trust I was not taking a liberty in entertaining him, sir?”

“Not a bit! If that’s your idea of a large afternoon, go ahead.”

“I happened to meet the young gentleman taking a walk with his father’s valet, sir, whom I used to know somewhat intimately in London, and I ventured to invite them both to join me here.”

“Well, never mind about him, Jeeves. Read this letter.” He gave it the up-and-down.

“Very disturbing, sir!” was all he could find to say.

“What are we going to do about it?”

“Time may provide a solution, sir.”

“On the other hand, it mayn’t—what?”

“Extremely true, sir.”

We’d got as far as this when there was a ring at the door. Jeeves shimmered off; and Cyril blew in, full of good cheer and blitheringness.

“I say, Wooster, old thing,” he said, “I want your advice. You know this jolly old part of mine. How ought I to dress it? What I mean is, the first act scene is laid in a hotel of sorts at about three in the afternoon. What ought I to wear, do you think?”

I wasn’t feeling fit for a discussion of gents’ suitings.

“You’d better consult Jeeves,” I said.

“A hot and by no means unripe idea! Where is he?”

“Gone back to the kitchen, I suppose.”

“I’ll smite the good old bell—shall I? Yes? No?”

“Right-oh!”

Jeeves poured silently in.

“Oh, I say, Jeeves,” began Cyril, “I just wanted to have a syllable or two with you. It’s this way—— Hullo, who’s this?”

I then perceived that the stout stripling had trickled into the room after Jeeves. He was standing near the door, looking at Cyril as if his worst fears had been realized. There was a bit of silence. The child remained there, drinking Cyril in for about half a minute; then he gave his verdict:

“Fish face!”

“Fish face!”

“Eh? What?” said Cyril.

The child, who had evidently been taught at his mother’s knee to speak the truth, made his meaning a trifle clearer.

“You’ve a face like a fish!”

“You’ve a face like a fish!”

He spoke as if Cyril was more to be pitied than censured, which I’m bound to say I thought rather decent and broad-minded of him.

I don’t mind admitting that whenever I looked at Cyril’s face I always had a feeling that he couldn’t have got that way without its being mostly his own fault. I found myself warming to this child. Absolutely, don’t you know! I liked his conversation.

It seemed to take Cyril a moment or two really to grasp the thing; and then you could hear the blood of the Bassington-Bassingtons begin to sizzle.

“Well, I’m dashed!” he said. “I’m dashed if I’m not!”

“I wouldn’t have a face like that,” proceeded the child, with a good deal of earnestness—“not if you gave me a million dollars!” He thought for a moment; then corrected himself. “Two million dollars!” he added.

Just what occurred then I couldn’t exactly say; but the next few minutes were a bit exciting. I take it that Cyril must have made a dive for the infant. Anyway, the air seemed pretty well congested with arms and legs and things. Something bumped into the Wooster waistcoat just round the third button, and I collapsed on the settee and rather lost interest in things for the moment. When I had unscrambled myself I found that Jeeves and the child had retired, and Cyril was standing in the middle of the room, snorting a bit.

“Who’s that frightful little brute, Wooster?”

“I don’t know. I never saw him before to-day.”

“I gave him a couple of tolerably juicy buffets before he legged it. I say, Wooster, that kid said a dashed odd thing: he yelled out something about Jeeves’ promising him a dollar if he called me—er—what he said.”

It sounded pretty unlikely to me.

“What would Jeeves do that for?”

“It struck me as rummy too.”

“Where would be the sense of it?”

“That’s what I can’t see.”

“I mean to say it’s nothing to Jeeves what sort of a face you have.”

“No!” said Cyril. He spoke a little coldly, I fancied. I don’t know why. “Well, I’ll be popping. Toodle-oo!”

“Pip-pip!”

It must have been about a week after this rummy little episode that George Caffyn called me up and asked me if I would care to go and see a run-through of his show. Ask Dad, it seemed, was to open out of town, in Schenectady, on the following Monday, and this was to be a sort of preliminary dress rehearsal.

A preliminary dress rehearsal, Old George explained, was the same as a regular dress rehearsal, inasmuch as it was apt to look like nothing on earth and last into the small hours; but it was more exciting because they wouldn’t be timing the piece, and consequently all the blighters who on these occasions let their angry passions rise would have plenty of scope for interruptions, with the result that a pleasant time would be had by all.

The thing was billed to start at eight o’clock. I rolled up at ten-fifteen, so as not to have too long to wait before they began. The dress parade was still going on. George was on the stage, talking to an absolutely round chappie with big spectacles and a practically hairless dome. I had seen George with the latter merchant once or twice at the club, and I knew he was Blumenfeld, the manager.

I waved to George, and slid into a seat at the back of the house, so as to be out of the way when the fighting started. Presently George hopped down off the stage and came and joined me; and fairly soon after that the curtain went down. The chappie at the piano whacked out a well-meant bar or two and the curtain went up again.

I can’t quite recall what the plot of Ask Dad was about, but I do know that it seemed able to jog along all right without much help from Cyril. I was rather puzzled at first. What I mean is, through brooding on Cyril and hearing him his part and listening to his views on what ought and what ought not to be done, I suppose I had a sort of impression rooted in the old bean that he was pretty well the backbone of the show, and that the rest of the company didn’t do much except go on and fill in when he happened to be off the stage.

I sat there for nearly half an hour, waiting for him to make his entrance, until I suddenly discovered he had been on from the start. He was, in fact, the rummy-looking plug-ugly who was now leaning against a potted palm a couple of feet from the O. P. side, trying to appear intelligent while the heroine sang a song about love being like something that for the moment has slipped my memory. After the second refrain he began to dance in company with a dozen other equally weird birds, the whole platoon giving rather the impression of a bevy of car conductors from the tall grass dressed up in their Sunday clothes for a swift visit to the city.

A painful spectacle for one who could see a vision of Aunt Agatha reaching for the hatchet and old Bassington-Bassington Senior putting on his strongest pair of hobnailed boots! Absolutely!

The dance had just finished, and Cyril and his pals had shuffled off into the wings, when a voice spoke from the darkness on my right:

“Pop!”

Old Blumenfeld clapped his hands, and the hero, who had just been about to get the next line off his diaphragm, cheesed it. I peered into the shadows. Who should it be but Jeeves’ little playmate with the freckles! He was now strolling down the aisle with his hands in his pockets, as if the place belonged to him. An air of respectful attention seemed to pervade the building.

“Pop,” said the stripling, “that number’s no good.”

“Pop,” said the stripling, “that number’s no good.”

Old Blumenfeld beamed over his shoulder.

“Don’t you like it, darling?”

“It’s a louse, pop!”

“You’re dead right.”

“You want something zippy there; something with a bit of jazz to it.”

“Quite right, my boy! I’ll make a note of it. All right. Go on!”

I turned to George, who was muttering to himself in rather an overwrought way.

“I say, George, old man, who the dickens is that kid?”

Old George groaned a bit hollowly, as if things were a trifle thick.

“I didn’t know he had crawled in! It’s Blumenfeld’s son. Now we’re going to have a Hades of a time!”

“Does he always run things like this?”

“Always!”

“But why does old Blumenfeld listen to him?”

“Nobody seems to know. It may be pure fatherly love, or he may regard him as a mascot. My own idea is that he thinks the kid has exactly the amount of intelligence of the average member of a Broadway audience, and that what makes a hit with him will please the general public; while, conversely, what he doesn’t like will be too rotten for anyone. The kid is a pest, a wart, and a pot of poison, and he should be strangled!”

The rehearsal went on. The hero got off his lines. There was a slight outburst of frightfulness between the stage manager and a voice named Bill that came from somewhere near the roof, the subject under discussion being where the devil Bill’s “ambers” were at that particular juncture. Then things went on again until the moment arrived for Cyril’s big scene.

I was still a trifle hazy about the plot; but I had got on to the fact that Cyril was some sort of an English peer who had come over to America doubtless for the best reasons. So far, he had had only two lines to say. One was “Oh, I say!” And the other was “Yes; by Jove!” But I seemed to recollect from hearing him his part that pretty soon he was due rather to spread himself. I sat back in my seat and waited for him to bob up. He bobbed up about five minutes later. Things had got a bit stormy by that time. The voice and the stage director had had another of their love feasts—this time something to do with why Bill’s “blues” weren’t on the job, or something. And almost as soon as that was over there was a bit of unpleasantness because a flowerpot fell off a window ledge and nearly brained the hero.

The atmosphere was consequently more or less hotted up when Cyril, who had been hanging about at the back of the stage with a squad of his village inseparables, breezed down the center and toed the mark for his most substantial chunk of entertainment. The heroine had been saying something—I forget what: something about love being something or not being something, if you follow me—and all the car conductors, with Cyril at their head, had begun to surge round her in the restless sort of way those chappies always do when there’s a number coming along.

Cyril’s first line was: “Oh, I say, you know; you mustn’t say that—really!” And it seemed to me he passed it over the larynx with a goodish deal of vim and je ne sais quoi. But—by Jove!—before the heroine had time for the comeback our little friend with the freckles had risen to lodge a protest.

“Pop!”

“Yes, darling?”

“That one’s no good!”

“Which one, darling?”

“The one with a face like a fish.”

“But they all have faces like fish, darling.”

The child seemed to see the justice of this objection. He became more definite:

“The ugly one.”

“Which ugly one? That one?” said Old Blumenfeld, pointing to Cyril.

“Yep! He’s rotten!”

“I thought so, myself.”

“He’s a pill!”

“You’re dead right, my boy! I’ve noticed it for some time.”

Cyril had been gaping a bit while these few remarks were in progress. He now shot down to the footlights. Even from where I was sitting, I could see that these harsh words had hit the old Bassington-Bassington family pride a frightful wallop. He started to get pink in the ears, and then in the nose, and then in the cheeks; until in about a quarter of a minute he looked pretty much like an explosion in a tomato cannery on a sunset evening.

“What the deuce do you mean?”

“What the deuce do you mean?” shouted Old Blumenfeld. “Don’t yell at me across the footlights!”

“I’ve a dashed good mind to come down and spank that little brute!”

“What?”

“A dashed good mind!”

Old Blumenfeld swelled like a pumped-up tire. He got rounder than ever.

“See here, mister—I don’t know your dam’ name——”

“My name’s Bassington-Bassington; and the jolly old Bassington-Bassingtons—I mean the Bassington-Bassingtons aren’t accustomed——”

Old Blumenfeld told him in a few brief words pretty much what he thought of the Bassington-Bassingtons and what they weren’t accustomed to. The whole strength of the company rallied round to enjoy his remarks. You could see them jutting out from the wings and protruding from behind trees.

“You’ve got to work good for my pop!” said the stout child, waggling his head reprovingly at Cyril.

“I don’t want any bally cheek from you!” said Cyril, gurgling a bit.

“What’s that?” barked Old Blumenfeld. “Do you know that this boy is my son?”

“Yes; I do,” said Cyril. “And you both have my sympathy!”

“You’re fired!’’ bellowed Old Blumenfeld, swelling a good bit more. “Get out of my theater!”

About half past ten next morning, just after I had finished lubricating the good old interior with a soothing cup of oolong, Jeeves filtered into my bedroom and said that Cyril was waiting to see me in the sitting room.

“How does he look, Jeeves?”

“Sir?”

“What does Mr. Bassington-Bassington look like?”

“It is hardly my place, sir, to criticize the facial peculiarities of your friends.”

“I don’t mean that. I mean: Does he appear peeved, and what not?”

“Not noticeably, sir. His manner is tranquil.”

“That’s rum!”

“Sir?”

“Nothing. Shoo him in, will you?”

I’m bound to say I had expected to see Cyril showing a few more traces of last night’s battle. I was looking for a bit of the overwrought soul and the quivering ganglions, if you know what I mean. He seemed pretty ordinary and quite fairly cheerful.

“Hullo, Wooster, old thing!”

“Cheero!”

“I just looked in to say good-by.”

“Good-by?”

“Yes; I’m off to Washington in an hour.” He sat down on the bed. “You know, Wooster, old top,” he went on, “I’ve been thinking it all over, and really it doesn’t seem quite fair to the jolly old guv’nor—my going on the stage, and so forth. What do you think?”

“I see what you mean.”

“I mean to say he sent me over here to broaden my jolly old mind, or words to that effect, don’t you know! And I can’t help thinking it would be a bit of a jar for the old boy if I gave him the bird and went on the stage instead. I don’t know if you understand me; but what I mean to say is that it’s a sort of question of conscience.”

“Can you leave the show without upsetting everything?”

“Oh, that’s all right. I’ve explained everything to Old Blumenfeld and he quite sees my position. Of course he’s sorry to lose me—said he didn’t see how he could fill my place, and all that sort of thing; but, after all, even if it does land him in a bit of a hole, I think I’m right in resigning my part. Don’t you?”

“Oh, absolutely!”

“I thought you’d agree with me. Well, I ought to be shifting. Awfully glad to have seen something of you, and all that sort of rot. Pip-pip!”

“Toodle-oo!”

He sallied forth, having told all those bally lies with the clear, blue, popeyed gaze of a young child. I rang for Jeeves. You know, ever since last night I had been exercising the old bean to some extent, and a good deal of light had dawned upon me.

“Jeeves?”

“Sir?”

“Did you put that pie-faced infant up to bullyragging Mr. Bassington-Bassington?”

“Sir?”

“Oh, you know what I mean. Did you tell him to get Mr. Bassington-Bassington sacked from the Ask Dad company?”

“I would not take such a liberty, sir.” He started to put out my clothes. “It is possible, however, that young Master Blumenfeld may have gathered from casual remarks of mine that I did not consider the stage altogether a suitable sphere for Mr. Bassington-Bassington.”

“I say, Jeeves, you know, you’re a bit of a marvel. A chappie can generally rely on you, don’t you know! Absolutely!”

“I endeavor to give satisfaction, sir.”

“And I’m frightfully obliged, if you know what I mean. Aunt Agatha would have had sixteen or seventeen fits if you hadn’t headed him off.”

“I fancy there might have been some little unpleasantness, sir. I am laying out the blue suit with the thin red stripe, sir. I fancy the effect will be pleasing.”

It’s a rummy thing; but I had finished breakfast and gone out and got as far as the elevator before I remembered what it was that I had meant to do to reward Jeeves for his really sporting behavior in this matter of the chump, Cyril. My heart warmed to the chappie. Absolutely!

It’s a rummy thing; but I had finished breakfast and gone out and got as far as the elevator before I remembered what it was that I had meant to do to reward Jeeves for his really sporting behavior in this matter of the chump, Cyril. My heart warmed to the chappie. Absolutely!

It cut me to the heart to do it, but I had decided to give him his way and let those purple socks pass out of my life. After all, there are times when a cove must make sacrifices. I was just going to nip back and break the glad news to him when the elevator came up; so I thought I would leave it until I got home.

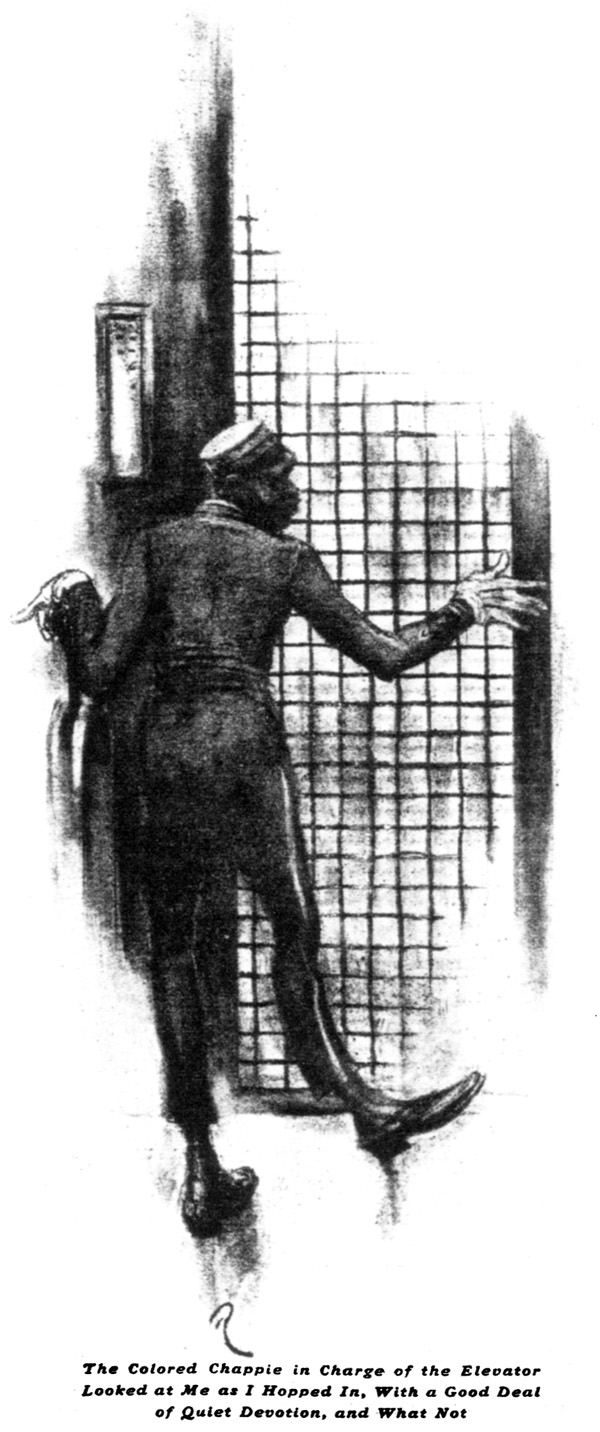

The colored chappie in charge of the elevator looked at me as I hopped in, with a good deal of quiet devotion, and what not.

“I wish to thank yo’, suh,” he said, “for yo’ kindness.”

“Eh? What?”

“Misto’ Jeeves done give me them purple socks, as you told him. Thank yo’ very much, suh!”

I looked down. The blighter was a blaze of mauve from the ankle bone southward. I don’t know when I’ve seen anything so dressy.

“Oh, ah! Not at all! Right-oh! Glad you like them,” I said.

Well, I mean to say—— What? Absolutely!

Compare the British magazine appearance of this story.

This story was adapted into chapters 9–10 of The Inimitable Jeeves; follow that link to annotations on this site.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums