The Strand Magazine, October 1914

IR GODFREY TANNER, K.C.M.G.,

was dining alone in his chambers at the Albany. Before him a plate of soup, so

clear and serene that it seemed wrong to ruffle its surface, relieved the snowy

whiteness of the tablecloth. Subdued lights shone on costly and tasteful

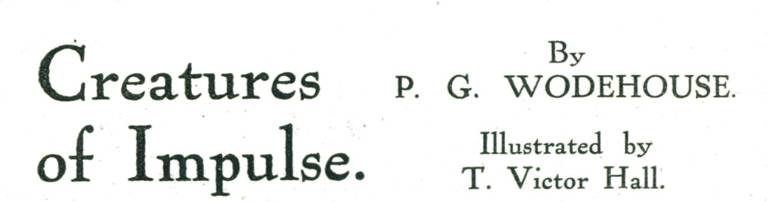

furniture. Behind him Jevons, for the last fifteen years his faithful servant,

wrestled decorously with a bottle of hock.

IR GODFREY TANNER, K.C.M.G.,

was dining alone in his chambers at the Albany. Before him a plate of soup, so

clear and serene that it seemed wrong to ruffle its surface, relieved the snowy

whiteness of the tablecloth. Subdued lights shone on costly and tasteful

furniture. Behind him Jevons, for the last fifteen years his faithful servant,

wrestled decorously with a bottle of hock.

A peaceful scene.

The thought passed through Sir Godfrey’s mind as he allowed his spoon to volplane slowly down into the golden lake that life was very pleasant. He had ample means. As a Colonial governor he had just that taste of power and authority which is enough for the sensible man; more might have spoiled him for the simpler pleasures of life; less would have left him restless and unsatisfied. He had had exactly enough, and was now ready to dream away the rest of his life in this exceedingly comfortable hermit’s cell, supported by an excellent digestion, ministered to by the faithful Jevons.

A muffled pop behind him occurred here almost as if there had been a stage direction for it. The sound seemed to emphasize the faithfulness of Jevons, working unseen in his master’s interests. It filled Sir Godfrey with a genial glow of kindliness. What a treasure Jevons was! What a model of what a gentleman’s servant should be! Existence without Jevons would be unthinkable.

As he mused Jevons silently manifested himself, bottle in hand. He filled Sir Godfrey’s glass.

“A little ice, Jevons.”

“Very good, Sir Godfrey.”

Sir Godfrey addressed himself once more to his soup. He glowed with benevolence. What an admirable fellow Jevons was! How long was it that they had been together? Fifteen years! And in all that time——

“Wow!” shrieked Sir Godfrey, and leaped from his chair with an agility highly creditable in one who strained his tailor’s tact almost to breaking-point every time he had to submit himself to the tape-measure.

For one moment he doubted his senses. It was incredible that that should have happened which had happened. Jevons was Jevons. An archbishop might have done this thing, but not Jevons.

But the evidence was incontrovertible. It was—at present—solid, not to be brushed aside.

Facts were facts, even if they seemed to outrage the fundamental laws of Nature.

Jevons, for fifteen years paragon of every possible virtue, had put a piece of ice down the back of his neck!

Sir Godfrey turned like a wounded lion. There was a terrible pause.

Jevons was certainly wonderful.

He met his employer’s gaze with grave solicitude.

“I think it would be wise, Sir Godfrey,” he said, “if you were to change your upper garments. The night is mild, but it is unwise to risk a chill. I will go and lay out another shirt.”

He disappeared silently into the bedroom, leaving Sir Godfrey staring at the spot where he had been.

Sir Godfrey received a clean shirt from his hands without a word. He had not intended the episode to proceed on these lines, but the practical sense of Jevons was too strong for him. Already the thaw had set in in earnest, and his back was both clammy and cold.

In fearful silence he changed his clothes. Then he wheeled round upon his companion of fifteen years.

“Now, then!” he snorted.

“I am extremely sorry that this should have happened, Sir Godfrey. I regret it exceedingly.”

“You do, eh? You’ll regret it more in a minute.”

“Just so, Sir Godfrey.”

There was something in the man’s imperturbability which ruined the speech which the ex-governor had intended to deliver. He had meant, when he once began, to go on for about ten minutes. But somehow Jevons’s attitude made it impossible to begin.

He condensed the meaning of the proposed speech into a question.

“What did you do it for? What—the—devil did you do it for?”

“I am extremely sorry, Sir Godfrey, but I just felt I had to. It sort of came over me. It is difficult to explain myself.”

“Difficult!”

“It was a kind of what I might describe as an impulse, sir. I was just coming from behind with the piece of ice in the tongs, thinking of nothing except to put it in the glass, when it suddenly crossed my mind that I’d been doing the same thing night in and night out for fifteen years, and it came over me what a long time it was and all. And then you leaned forward to drink the soup. And somehow I just couldn’t resist it. I now regret it exceedingly.”

Sir Godfrey gulped.

“You’ll go to-morrow.”

Jevons bowed.

“Shall I serve the fish, Sir Godfrey?”

He seemed to regard the incident as closed.

Dinner was resumed in silence. Sir Godfrey’s mind was still in a whirl. All he realized clearly was that the end of the world had come. He had dismissed Jevons, and without Jevons life was impossible. But he was not going to alter his decision. By Gad, no! not if he had to spend the rest of his existence in beastly hotels being maddened to distraction by a set of blanked incompetents who were probably foreign spies. And that seemed to him at the moment his only course, for the idea of engaging a successor to the victim of impulse was too bizarre to be grappled with yet. At whatever cost to himself, Jevons must go. That was settled and done with.

“I mean it,” he snapped, over his shoulder, as the other filled his liqueur-glass.

“Sir?”

“I say I mean it. What I said. You must go.”

“Just so, Sir Godfrey.”

He placed the cigars on the table. Sir Godfrey selected one, cracked the end of it, and placed it in the flame which his still faithful servant held for him. It was a magnificent cigar, and the first puff almost softened him to the extent of changing his mind. But dignity jerked at the reins.

“Of course I’ll give you a character.”

“Thank you, Sir Godfrey, but I do not feel as if I could take service with anybody but yourself. I have saved money. I shall retire.”

“Please yourself.”

“Just so, Sir Godfrey.”

“Leave me your address.”

“Sir?”

Sir Godfrey scowled. He was feeling nervous. More, there was a suggestion of a death-bed parting about this interview which he found strangely weakening. Fifteen years! As Jevons had said, it was a long time.

“Your address. You know perfectly well that I promised you a small—er—confound it!—the pension, man!”

“I had imagined that after what has occurred——”

“Don’t be a fool. That will be all. I am going to the club. I shall not want you any more to-night.”

“Very good, sir.”

He closed the door softly. Sir Godfrey sat on, chewing the end of his cigar.

A week later Sir Godfrey sat in his private sitting-room at the Hotel Guelph and kicked moodily at a foot-stool.

“This,” he said to himself, “is perfectly infernal.”

He got up and began to pace the room.

“If I stop any longer in this pot-house I shall go mad.”

Of course he was doing the place an injustice. The Guelph is one of the three best hotels in London. The management pride themselves on making guests as comfortable as modern ingenuity will allow. There was every possible convenience in this suite to which Sir Godfrey had fled from an Albany which for him was now haunted.

And Sir Godfrey spoke of it as a pot-house. But then, the Hotel Guelph had one defect which outweighed all its merits. It could not supply him with a valet who had been with him for fifteen years. Losing Jevons was like losing a leg.

But he was not going to take him back. All his life he had been a victim to what his admirers called determination and his detractors pig-headedness, and he never reversed a decision.

“I’ll get out of here to-day,” he said to himself.

A thought struck him. “I’ll go and spend a week or two with George.”

He wondered why he had not thought of it before. He saw now where his initial mistake had lain: he had tried to carry on, without Jevons, the sort of life with which Jevons had been so closely associated. It was all very well to leave the Albany and move to the Guelph, but that was not enough. He was still in the groove in which he had been in the days before Jevons had left him. He still spent his evenings at his club, rode in the Row, and so on—actions irretrievably connected with Jevons. What he must do, he decided, was to get temporarily into some entirely different milieu. He must go to the country. And it was the thought of the country which had suggested George.

George Tanner kept a private school in Kent. What was more, he had started this school on money lent to him by Sir Godfrey. The money had since been returned, with interest, for George’s venture had proved a success; but Sir Godfrey considered that his nephew had cause to be grateful to him, and consequently saw no reason why he should not descend upon him in the middle of term demanding food and shelter. He did not even prepay the telegram in which he announced his visit, but arrived on the heels of it, sure of his welcome.

George received him with a rather worried geniality. He stood in awe of his uncle, as did most of those who knew him. Sir Godfrey in years gone by had spanked him with a hair-brush for breaking his bedroom-window with a tennis-ball, and this and similar episodes of the stormy past coloured George’s attitude towards him, even though he was now in the thirties and had begun to grow grey at the temples. Besides, in a school even the most genial visitor is not an unmixed blessing. And George’s school was peculiar in the respect that there was no sharp division between the boys’ part of the house and that of the proprietor. It was a rambling old mansion, in which the inhabitants lived like a large family. Sir Godfrey had not anticipated this.

There were boys everywhere, in the house and out of it; boys who yelled unexpectedly in a man’s ear; boys who shot out of doorways at incredible rates of speed within a hair’s breadth of a man’s prominent and sensitive solar plexus; boys who, when once their shyness had worn off, asked a man endless questions on every subject under the sun. Nephew George seemed rather to enjoy this sort of thing, but in the first few days of his visit it nearly drove Sir Godfrey mad.

A hundred times he was on the point of leaving, but every time the thought of solitude in an hotel kept him where he was. And then, one morning as he lay in bed, he achieved an attitude of mind which he felt would enable him to bear his present mode of life with fortitude, if not with enjoyment.

This visit to George’s school, he told himself, must be regarded in the light of a sort of mental discipline. It was a kind of Purgatory. A man of his years could not change his habits smoothly, like a motor-car changing speeds. There must be an interval, the more unpleasant and unlike his old life the better, for thus would it stick the more firmly in his memory, and form the more admirable corrective to vain regret. For the rest of his life, as he sat in his solitary hotel sitting-room, instead of mourning the fact that he was not at the Albany with Jevons he would be thanking a kindly Providence that he was not at his Nephew George’s school.

It was the same process of thought which leads the philosopher suffering from a blend of toothache and earache to cheer himself up by reflecting how much worse it would be if he had a combination of rheumatism and St. Vitus’s dance.

He had found the solution. It was simply wonderful what a difference it made. His whole nervous system became miraculously soothed. Where when a sprinting boy whizzed past his waistcoat he had puffed and trembled for minutes afterwards in an ecstasy of fear and indignation, he now stood firm and calm, and sometimes even achieved an indulgent smile.

As the days passed the indulgent smile became more and more frequent. The process was so subtle that he could not have said when it had begun, but frequently now he could almost have declared that he was enjoying himself. He was beginning to revise his views upon the boys. These boys here, whom he had lumped together in his mind with all other existing small boys under the collective head of nuisances, began to develop individual characters. With something of the thrill of a scientific discovery, he awoke to the fact that boys were human beings, who did things for definite reasons and not purely from innate deviltry. The reason, for instance, why Thomas Billing, aged eleven, had eaten a slice of bread covered with brown boot-polish, thereby acquiring a severe bout of sickness and a heavy punishment, was that Rupert Atkinson, aged fourteen, and Alexander Jones, aged twelve, had betted him he wouldn’t. He had done it, in short, not for the pleasure of making himself ill, but to keep his word and preserve his self-respect. Nations have gone to war for reasons less compelling.

Thomas Billing explained the ethics of this particular episode to Sir Godfrey in person; and it may be said that the latter’s rejuvenation really began from that conversation. For it led to what was practically a friendship between them, and in the constant society of Thomas Sir Godfrey renewed his youth.

It was so long since he had been a boy that the process of rejuvenation hung fire at the start; but, once started, it was rapid. In the third week of his uncle’s visit, Nephew George, with the feeling of one who sees miracles, gazed, fascinated, at the spectacle of his guest playing cricket in the stable-yard. He was playing unskilfully, but with extreme energy, and his face, when he joined George, was damp and scarlet.

A belated sense of his dignity awoke in Sir Godfrey. He felt that it behoved him to keep George in a state of respectful subjection.

“I have been doing my best to amuse these little fellows, George.”

“I was watching you.”

Sir Godfrey coughed a little self-consciously.

“They seemed to wish me to join in their game. I did not like to disappoint them. I suppose, many years ago, one would have found a positive pleasure in ridiculous foolery of that sort. It seems hardly credible, but I imagine there was a time when I might really have enjoyed it.”

“It’s a good game.”

“For children, possibly. Merely for children. However, it certainly appears to be capital exercise. My doctor strongly recommended me exercise. I—I have half a mind to play again to-morrow.”

“If you enjoy it——”

“Enjoy is altogether too strong a word. If I decide to play, it will be entirely for the sake of exercise. A man of my build requires a certain amount of exercise. My doctor was emphatic.”

“Quite right.”

“By Gad, I’ll do it every day!” said Sir Godfrey.

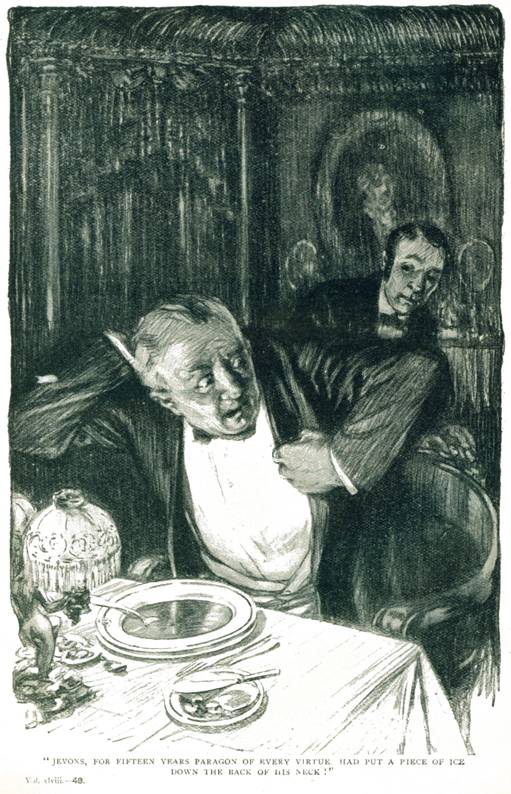

One morning, towards the end of the fourth week of his visit, the ex-governor, sunning himself after breakfast, came upon his young friend, Thomas Billing, plainly depressed. The morning was so perfect, and he himself was feeling so entirely at peace with the world, that Sir Godfrey noted the depression as a remarkable phenomenon. That he should have noted it at all is proof of the alteration in his outlook. A week or so before he would simply have seen a small boy, with his hands in his pockets, kicking pebbles; and, if he had given the matter a second thought, would merely have felt relieved that the boy was not shouting or rushing about. The humanizing process had, however, sharpened his faculties, and he now perceived clearly that on Thomas Billing’s youthful mind there was a burden, that for some reason Black Care was perched upon Thomas Billing’s youthful back.

“What’s the matter, my boy?” he inquired.

“It’s an air-gun,” said Thomas, with a certain vagueness.

“An air-gun?”

“My air-gun. He’s confiscated it.”

The pronoun “he,” used without reference to a foregoing substantive, indicated Nephew George.

Sir Godfrey acted in a manner which would have amazed him if he could have foreseen it a few weeks back. Now there seemed nothing unusual about it at all. He took out a shilling. He was feeling quite surprisingly in sympathy with the boy.

“Cheer up, my boy,” he said. “Buy yourself something with this, and forget about it.”

He proceeded upon his way, leaving Thomas in a state of speechless gratitude.

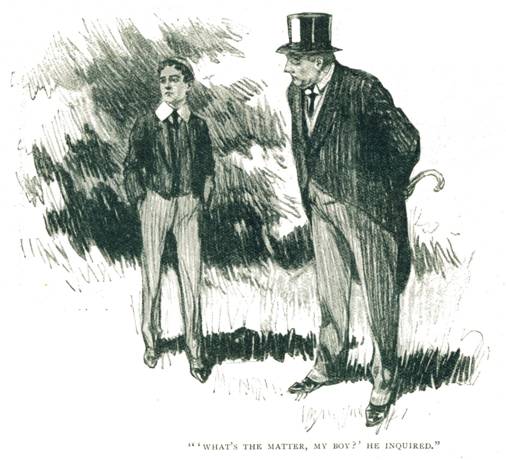

Sir Godfrey went to his nephew’s study. He had not yet finished reading the morning paper, and it was usually to be found there. It was not immediately visible. He looked round the room. His eye was caught by a lethal weapon lying on the window-sill.

He picked it up.

There is probably no action possible to a man which so unfailingly restores his vanished youth as the handling of an air-gun. There is something in the feel of the wood and the gleam of the steel which rolls away the years as if by some magic spell. Toying with the confiscated gun of Thomas Billing, Sir Godfrey was a boy again. How long was it since he had handled one of these things? Years? Centuries? Not a bit of it. A few minutes, he was prepared to swear.

“By Gad,” he murmured, as he took imaginary aim, “I’ve killed sparrows with these things! By Gad I have! It all comes back to me, by Gad!”

He ran his eye lovingly along the barrel.

Crime is the result, in nine cases out of ten, of impulse. It is the chemical outcome of opportunity reacting upon a mood. A man commits murder because, when in a certain mood, he finds a knife ready to his hand. Neither the mood nor the knife alone would produce the crime.

Sir Godfrey was in a dangerously-excited mood. He was not himself. He was, indeed, at that moment, a matter of fifty years younger than himself. And to him, in this state of mind, Fate presented, almost simultaneously, a box of ammunition and Herbert, the school gardener.

The box lay open on the window-sill. The broad back view of Herbert appeared beside a flower-bed not twenty yards away.

No boy could have resisted the temptation; and Sir Godfrey in the last five minutes had become a boy.

He took careful aim and fired.

It was stupendous. Herbert, a good two hundred pounds of solid flesh, leaped like a young gazelle. From behind the curtain where he lurked Sir Godfrey, with gleaming eyes, saw him turn and turn again, scanning the world for the author of this outrage. For a full minute he looked accusingly at the house, while the house looked back at him with its empty windows. Then, his lips moving silently, he bent to his work again.

Sir Godfrey crept from his hiding-place and dipped his fingers into the box of bullets.

If it were not for the aftermath, crime would be the jolliest thing in the world. Sir Godfrey discovered this. His actual crime gave him the happiest five minutes he could recall in a long and not ill-spent life. The phut of the bullets on Herbert’s corduroys had been music to his ears. During the actual engagement he had been quite drunk with sinful pride at the accuracy of his aim and the Red Indian cunning with which he secreted his portly form behind the curtain at the exact moment when his victim faced wrathfully round.

And then his wild mood vanished as swiftly as it had come. One moment he was a happy child, pumping lead into the lower section of a gardener; the next, a man of age, position, and respectability, acutely conscious of having committed an unpardonable assault on a harmless fellow-citizen. He sank back into a convenient chair, his face a light mauve, the nearest approach Nature would permit to an ashen pallor.

Ghastly thoughts raced, jostling each other, through his brain. Discovery—action for assault and battery—vindictive prosecutor—heavy fine—query: imprisonment?—strong remarks from the Bench—ruined reputation—or, worse, verdict of insanity—evening of life spent in padded cell!

And he was the man who had dismissed Jevons, good, faithful, honest Jevons, after fifteen years of service, for a mere peccadillo.

At dinner that night Nephew George appeared amused.

“It’s nothing to laugh at, really,” he said, “but you can’t help it. I was laughing when I licked him—Young Tom Billing. Apparently he spent a happy morning shooting at the gardener with an air-gun. With a confiscated air-gun, too! You never know what the little brutes——”

Sir Godfrey uttered a strangled gurgle.

“George! George, my dear boy! What are you saying?”

“Your friend Tom——”

“But how——?”

“The gardener came to me and made a complaint. I harangued the school and invited the criminal to confess. The Billing child stepped forward.”

“He said that he did it!”

“Yes. Why, what’s the matter, uncle?”

Sir Godfrey drew a deep breath.

“Nothing, my boy; nothing at all,” he said.

Sir Godfrey writhed in his bed, a chastened man. Relief, shame, and a stunned admiration for the quixotic generosity of the younger generation forbade sleep. He could understand the whole thing so clearly. This boy Billing must have seen the episode, realized the consequences if it were brought home to the real criminal, and, prompted by pure amiability—supplemented possibly by gratitude for that shilling—sacrificed himself to save his friend. Among the few pleasant thoughts which came to Sir Godfrey that night was the resolve to make Thomas Billing his sole heir, give him a pony, buy him everything he could suggest, and take him to the pantomime next Christmas.

He met the young hero next morning after breakfast. To his surprise, his benefactor seemed more than a little sheepish. He shuffled his feet. He even blushed.

Finally he spoke.

“I hope you aren’t frightfully sick about it, sir. I know it was frightful cheek my pretending I had done it, after you’d thought of it and all that; but I thought you wouldn’t mind. It was awfully decent of you not to give me away. You don’t know what a difference it makes to a chap if chaps think he’s done a thing like that. It makes them look up to you frightfully. I only came here this term, and I’m too small to be much good at games just yet, so of course they don’t think much of me. But now, you see, it’s all right.”

Sir Godfrey was silent.

“You don’t really mind my saying it was me, do you?” said Thomas, anxiously. “Of course, if you say I must, I’ll tell them that it was really you. It’ll make things rather rotten for me, but if you want me to——”

“By no means. By no means. By—ah!—by no means.”

“Thanks awfully, sir,” said Thomas, gratefully.

There was a pause.

“I expect you really think it was frightful cheek, don’t you, sir? I honestly didn’t mean to do it, because I’d seen the whole thing and I knew I’d no right to pretend it was me. But when He asked who had done it, it—it sort of came over me.”

Sir Godfrey uttered a startled cry.

“The impulse of the moment!”

“Yes, sir.”

Sir Godfrey had produced paper and was writing.

“I want you to take a telegram for me at once to the village, my little man,” he said. “I will tell Mr. Tanner I sent you. It is most important. Here it is. Can you read it? My handwriting is shaky this morning. I am much disturbed, much disturbed.”

Thomas scanned the message.

“Jones, 193, Adelaide Street, Fulham Road, London.”

“Jevons, Jevons. Jevons, my boy; not Jones. J-e-v-o-n-s.”

“ ‘Be prepared to rejoin me in—in——’ ”

“ ‘Instantly. Everything forgiven. Await letter. Godfrey Tanner.’ There, you have it now. Run with it at once. It is most—it is vitally important.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums