The Strand Magazine, October 1925

THE summer day was drawing to a close. Over the terrace outside the club-house the chestnut trees threw long shadows, and such bees as still lingered in the flower-beds had the air of tired business men who are about ready to shut up the office and go off to dinner and a musical comedy. The Oldest Member, stirring in his favourite chair, glanced at his watch and yawned.

As he did so, from the neighbourhood of the eighteenth green, hidden from his view by the slope of the ground, there came suddenly a medley of shrill animal cries, and he deduced that some belated match must just have reached a finish. His surmise was correct. The babble of voices drew nearer, and over the brow of the hill came a little group of men. Two, who appeared to be the ringleaders in the affair, were short and stout. One was cheerful, the other dejected. The rest of the company consisted of friends and adherents; and one of these, a young man who seemed to be amused, strolled to where the Oldest Member sat.

“What,” inquired the Sage, “was all the shouting for?” The young man sank into a chair and lighted a cigarette.

“Perkins and Broster,” he said, “were all square at the seventeenth, and they raised the stakes to fifty pounds. They were both on the green in seven, and Perkins had a two-foot putt to halve the match. He missed it by six inches. They play pretty high, those two.”

“It is a curious thing,” said the Oldest Member, “that men whose golf is of a kind that makes hardened caddies wince always do. The more competent a player, the smaller the stake that contents him. It is only when you get down into the submerged tenth of the golfing world that you find the big gambling. However, I would not call fifty pounds anything sensational in the case of two men like Perkins and Broster. They are both well provided with the world’s goods. If you would care to hear the story——”

The young man’s jaw fell a couple of notches.

“I had no idea it was so late,” he bleated. “I ought to be——”

“——of a man who played for really high stakes——”

“I promised to——”

“——I will tell it to you,” said the Sage, affectionately attaching himself to the other’s buttonhole.

“Look here,” said the young man, sullenly, “it isn’t one of those stories about two men who fall in love with the same girl and play a match to decide which is to marry her, is it? Because, if so——”

“The stake to which I allude,” said the Oldest Member, “was something far higher and bigger than a woman’s love. Shall I proceed?”

“All right,” said the young man, resignedly. “Snap into it.”

IT has been well said—I think by the man who wrote the sub-titles for “Cage-Birds of Society” (began the Oldest Member)—that wealth does not always bring happiness. It was so with Bradbury Fisher, the hero of the story which I am about to relate. One of America’s most prominent tainted millionaires, he had two sorrows in life—his handicap refused to stir from twenty-four and his wife disapproved of his collection of famous golf relics. Once, finding him crooning over the trousers in which Ouimet had won his historic replay against Vardon and Ray in the American Open, she had asked him why he did not collect something worth while like Old Masters or first editions.

Worth while! Bradbury had forgiven, for he loved the woman, but he could not forget.

For Bradbury Fisher, like so many men who have taken to the game in middle age, after a youth misspent in the pursuits of commerce, was no half-hearted enthusiast. Although he still occasionally descended on Wall Street in order to pry the small investor loose from another couple of million, what he really lived for now was golf and his collection. He had begun the collection in his first year as a golfer, and he prized it dearly. And when he reflected that his wife had stopped him purchasing J. H. Taylor’s shirt-stud, which he could have had for a few hundred pounds, the iron seemed to enter into his soul.

The distressing episode had occurred in London, and he was now on his way back to New York, having left his wife to continue her holiday in England. All through the voyage he remained moody and distrait; and at the ship’s concert, at which he was forced to take the chair, he was heard to observe to the purser that if the alleged soprano who had just sung “My Little Grey Home in the West” had the immortal gall to take a second encore he hoped that she would trip over a high note and dislocate her neck.

SUCH was Bradbury Fisher’s mood throughout the ocean journey, and it remained constant until he arrived at his palatial home at Goldenville, Long Island, where, as he sat smoking a moody after-dinner cigar in the Versailles drawing-room, Blizzard, his English butler, informed him that Mr. Gladstone Bott desired to speak to him on the telephone.

“Tell him to go and boil himself,” said Bradbury.

“Very good, sir.”

“No, I’ll tell him myself,” said Bradbury. He strode to the telephone. “Hullo!” he said, curtly.

He was not fond of this Bott. There are certain men who seem fated to go through life as rivals. It was so with Bradbury Fisher and J. Gladstone Bott. Born in the same town within a few days of one another, they had come to New York in the same week; and from that moment their careers had run side by side. Fisher had made his first million two days before Bott, but Bott’s first divorce had got half a column and two sticks more publicity than Fisher’s.

At Sing-Sing, where each had spent several happy years of early manhood, they had run neck and neck for the prizes which that institution has to offer. Fisher secured the position of catcher on the baseball nine in preference to Bott, but Bott just nosed Fisher out when it came to the choice of a tenor for the glee club. Bott was selected for the debating contest against Auburn, but Fisher got the last place on the crossword puzzle team, with Bott merely first reserve.

They had taken up golf simultaneously, and their handicaps had remained level ever since. Between such men it is not surprising that there was little love lost.

“Hullo!” said Gladstone Bott. “So you’re back? Say, listen, Fisher. I think I’ve got something that’ll interest you. Something you’ll be glad to have in your golf collection.”

Bradbury Fisher’s mood softened. He disliked Bott, but that was no reason for not doing business with him. And though he had little faith in the man’s judgment, it might be that he had stumbled upon some valuable antique. There crossed his mind the comforting thought that his wife was three thousand miles away and that he was no longer under her penetrating eye—that eye which, so to speak, was always “about his bath and about his bed and spying out all his ways.”

“I’ve just returned from a trip down South,” proceeded Bott, “and I have secured the authentic baffy used by Bobbie Jones in his first important contest—the Infants’ All-In Championship of Atlanta, Georgia, open to those of both sexes not yet having finished teething.”

Bradbury gasped. He had heard rumours that this treasure was in existence, but he had never credited them.

“You’re sure?” he cried. “You’re positive it’s genuine?”

“I have a written guarantee from Mr. Jones, Mrs. Jones, and the nurse.”

“How much, Bott, old man?” stammered Bradbury. “How much do you want for it, Gladstone, old top? I’ll give you a hundred thousand dollars.”

“Ha!”

“Five hundred thousand.”

“Ha, ha!”

“A million.”

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“Two million.”

“Ha, ha, ha, ha!”

Bradbury Fisher’s strong face twisted like that of a tortured fiend. He registered in quick succession rage, despair, hate, fury, anguish, pique, and resentment. But when he spoke again his voice was soft and gentle.

“Gladdy, old socks,” he said, “we have been friends for years.”

“No, we haven’t,” said Gladstone Bott.

“Yes, we have.”

“No, we haven’t.”

“Well, anyway, what about two million five hundred?”

“Nothing doing. Say, listen. Do you really want that baffy?”

“I do, Botty, old egg, I do indeed.”

“Then listen. I’ll exchange it for Blizzard.”

“For Blizzard?” quavered Fisher.

“For Blizzard.”

It occurs to me that, when describing the closeness of the rivalry between these two men, I may have conveyed the impression that in no department of life could either claim a definite advantage over the other. If that is so, I erred. It is true that in a general way, whatever one had, the other had something equally good to counterbalance it; but in just one matter Bradbury Fisher had triumphed completely over Gladstone Bott. Bradbury Fisher had the finest English butler on Long Island.

Blizzard stood alone. There is a regrettable tendency on the part of English butlers to-day to deviate more and more from the type which made their species famous. The modern butler has a nasty knack of being a lissom young man in perfect condition who looks like the son of the house. But Blizzard was of the fine old school. Before coming to the Fisher home he had been for fifteen years in the service of an earl, and his appearance suggested that throughout those fifteen years he had not let a day pass without its pint of port. He radiated port and pop-eyed dignity. He had splay feet and three chins, and when he walked his curving waistcoat preceded him like the advance guard of some royal procession.

Blizzard stood alone. There is a regrettable tendency on the part of English butlers to-day to deviate more and more from the type which made their species famous. The modern butler has a nasty knack of being a lissom young man in perfect condition who looks like the son of the house. But Blizzard was of the fine old school. Before coming to the Fisher home he had been for fifteen years in the service of an earl, and his appearance suggested that throughout those fifteen years he had not let a day pass without its pint of port. He radiated port and pop-eyed dignity. He had splay feet and three chins, and when he walked his curving waistcoat preceded him like the advance guard of some royal procession.

From the first, Bradbury had been perfectly aware that Bott coveted Blizzard, and the knowledge had sweetened his life. But this was the first time he had come out into the open and admitted it.

“Blizzard?” whispered Fisher.

“Blizzard,” said Bott, firmly. “It’s my wife’s birthday next week, and I’ve been wondering what to give her.”

Bradbury Fisher shuddered from head to foot, and his legs wobbled like asparagus stalks. Beads of perspiration stood out on his forehead. The serpent was tempting him—tempting him grievously.

“You’re sure you won’t take three million—or four—or something like that?”

“No; I want Blizzard.”

Bradbury Fisher passed his handkerchief over his streaming brow.

“So be it,” he said in a low voice.

The Jones baffy arrived that night, and for some hours Bradbury Fisher gloated over it with the unmixed joy of a collector who has secured the prize of a lifetime. Then, stealing gradually over him, came the realization of what he had done.

He was thinking of his wife and what she would say when she heard of this. Blizzard was Mrs. Fisher’s pride and joy. She had never, like the poet, nursed a dear gazelle, but, had she done so, her attitude towards it would have been identical with her attitude towards Blizzard. Although so far away, it was plain that her thoughts still lingered with the treasure she had left at home, for on his arrival Bradbury had found three cables awaiting him.

The first ran:—

“How is Blizzard? Reply.”

The second:—

“How is Blizzard’s sciatica? Reply.”

The third:—

“Blizzard’s hiccups. How are they? Suggest Doctor Murphy’s Tonic Swamp-Juice. Highly spoken of. Three times a day after meals. Try for week and cable result.”

It did not require a clairvoyant to tell Bradbury that, if on her return she found that he had disposed of Blizzard in exchange for a child’s cut-down baffy, she would certainly sue him for divorce. And there was not a jury in America that would not give their verdict in her favour without a dissentient voice. His first wife, he recalled, had divorced him on far flimsier grounds. So had his second, third, and fourth. And Bradbury loved his wife. There had been a time in his life when, if he lost a wife, he had felt philosophically that there would be another along in a minute; but, as a man grows older, he tends to become set in his habits, and he could not contemplate existence without the company of the present incumbent.

What, therefore, to do? What, when you came right down to it, to do?

There seemed no way out of the dilemma. If he kept the Jones baffy, no other price would satisfy Bott’s jealous greed. And to part with the baffy, now that it was actually in his possession, was unthinkable.

And then, in the small hours of the morning, as he tossed sleeplessly on his Louis Quinze bed, his giant brain conceived a plan.

ON the following afternoon he made his way to the club-house, and was informed that Bott was out playing a round with another millionaire of his acquaintance. Bradbury waited, and presently his rival appeared.

“Hey!” said Gladstone Bott, in his abrupt, uncouth way. “When are you going to deliver that butler?”

“I will make the shipment at the earliest date,” said Bradbury.

“I was expecting him last night.”

“You shall have him shortly.”

“What do you feed him on?” asked Gladstone Bott.

“Oh, anything you have yourselves. Put sulphur in his port in the hot weather. Tell me, how did your match go?”

“He beat me. I had rotten luck.”

Bradbury Fisher’s eyes gleamed. His moment had come.

“Luck?” he said. “What do you mean, luck? Luck has nothing to do with it. You’re always beefing about your luck. The trouble with you is that you play rottenly.”

“Luck?” he said. “What do you mean, luck? Luck has nothing to do with it. You’re always beefing about your luck. The trouble with you is that you play rottenly.”

“What?”

“It is no use trying to play golf unless you learn the first principles and do it properly. Look at the way you drive.”

“What’s wrong with my driving?”

“Nothing, except that you don’t do anything right. In driving, as the club comes back in the swing, the weight should be shifted by degrees, quietly and gradually, until, when the club has reached its topmost point, the whole weight of the body is supported by the right leg, the left foot being turned at the time and the left knee bent in toward the right leg. But, regardless of how much you perfect your style, you cannot develop any method which will not require you to keep your head still so that you can see your ball clearly.”

“Hey!”

“It is obvious that it is impossible to introduce a jerk or a sudden violent effort into any part of the swing without disturbing the balance or moving the head. I want to drive home the fact that it is absolutely essential to——”

“Hey!” cried Gladstone Bott.

The man was shaken to the core. From the local pro, and from scratch men of his acquaintance, he would gladly have listened to this sort of thing by the hour, but to hear these words from Bradbury Fisher, whose handicap was the same as his own and out of whom it was his unperishable conviction that he could hammer the tar any time he got him out on the links, was too much.

“Where do you get off,” he demanded, heatedly, “trying to teach me golf?”

Bradbury Fisher chuckled to himself. Everything was working out as his subtle mind had foreseen.

“My dear fellow,” he said, “I was only speaking for your good.”

“I like your nerve! I can lick you any time we start.”

“It’s easy enough to talk.”

“I trimmed you twice the week before you sailed to England.”

“Naturally,” said Bradbury Fisher, “in a friendly round, with only a few thousand dollars on the match, a man does not extend himself. You wouldn’t dare to play me for anything that really mattered.”

“I’ll play you when you like for anything you like.”

“Very well. I’ll play you for Blizzard.”

“Against what?”

“Oh, anything you please. How about a couple of railroads?”

“Make it three.”

“Very well.”

“Next Friday suit you?”

“Sure,” said Bradbury Fisher.

It seemed to him that his troubles were over. Like all twenty-four handicap men, he had the most perfect confidence in his ability to beat all other twenty-four handicap men. As for Gladstone Bott, he knew that he could disembowel him any time he was able to lure him out of the club-house.

NEVERTHELESS, as he breakfasted on the morning of the fateful match, Bradbury Fisher was conscious of an unwonted nervousness. He was no weakling. In Wall Street his phlegm in moments of stress was a byword. On the famous occasion when the B. and G. crowd had attacked C. and D., and in order to keep control of L. and M. he had been compelled to buy so largely of S. and T., he had not turned a hair. And yet this morning, in endeavouring to prong up segments of bacon, he twice missed the plate altogether and on a third occasion speared himself in the cheek with his fork. The spectacle of Blizzard, so calm, so competent, so supremely the perfect butler, unnerved him.

“I am jumpy to-day, Blizzard,” he said, forcing a laugh.

“Yes, sir. You do, indeed, appear to have the willies.”

“Yes. I am playing a very important golf-match this morning.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“I must pull myself together, Blizzard.”

“Yes, sir. And, if I may respectfully make the suggestion, you should endeavour, when in action, to keep the head down and the eye rigidly upon the ball.”

“I will, Blizzard, I will,” said Bradbury Fisher, his keen eyes clouding under a sudden mist of tears. “Thank you, Blizzard, for the advice.”

“Not at all, sir.”

“How is your sciatica, Blizzard?”

“A trifle improved, I thank you, sir.”

“And your hiccups?”

“I am conscious of a slight, though possibly only a temporary, relief, sir.”

“Good,” said Bradbury Fisher.

He left the room with a firm step; and, proceeding to his library, read for awhile portions of that grand chapter in James Braid’s “Advanced Golf” which deals with driving into the wind. It was a fair and cloudless morning, but it was as well to be prepared for emergencies. Then, feeling that he had done all that could be done, he ordered the car and was taken to the links.

Gladstone Bott was awaiting him on the first tee, in company with two caddies. A curt greeting, a spin of the coin, and Gladstone Bott, securing the honour, stepped out to begin the contest.

ALTHOUGH there are, of course, endless sub-species in their ranks, not all of which have yet been classified by science, twenty-four handicap golfers may be stated broadly to fall into two classes, the dashing and the cautious—those, that is to say, who endeavour to do every hole in a brilliant one and those who are content to win with a steady nine. Gladstone Bott was one of the cautious brigade. He fussed about for a few moments like a hen scratching gravel, then with a stiff quarter-swing sent his ball straight down the fairway for a matter of seventy yards, and it was Bradbury Fisher’s turn to drive.

Now, normally, Bradbury Fisher was essentially a dasher. It was his habit, as a rule, to raise his left foot some six inches from the ground and, having swayed forcefully back on to his right leg, to sway sharply forward again and lash out with sickening violence in the general direction of the ball. It was a method which at times produced excellent results, though it had the flaw that it was somewhat uncertain. Bradbury Fisher was the only member of the club, with the exception of the club champion, who had ever carried the second green with his drive; but, on the other hand, he was also the only member who had ever laid his drive on the eleventh dead to the pin of the sixteenth.

But to-day the magnitude of the issues at stake had wrought a change in him. Planted firmly on both feet, he fiddled at the ball in the manner of one playing spillikens. When he swung, it was with a swing resembling that of Gladstone Bott; and, like Bott, he achieved a nice, steady, rainbow-shaped drive of some seventy yards straight down the middle. Bott replied with an eighty-yard brassy shot. Bradbury held him with another. And so, working their way cautiously across the prairie, they came to the green, where Bradbury, laying his third putt dead, halved the hole.

The second was a repetition of the first, the third and fourth repetitions of the second. But on the fifth green the fortunes of the match began to change. Here Gladstone Bott, faced with a fifteen-foot putt to win, smote his ball firmly off the line, as had been his practice at each of the preceding holes, and the ball, hitting a worm-cast and bounding off to the left, ran on a couple of yards, hit another worm-cast, bounded to the right, and finally, bumping into a twig, leaped to the left again and clattered into the tin.

“One up,” said Gladstone Bott. “Tricky, some of these greens are. You have to gauge the angles to a nicety.”

At the sixth a donkey in an adjoining field uttered a raucous bray just as Bott was addressing his ball with a mashie-niblick on the edge of the green. He started violently and, jerking his club with a spasmodic reflex action of the forearm, holed out.

“Nice work,” said Gladstone Bott.

The seventh was a short hole, guarded by two large bunkers between which ran a narrow footpath of turf. Gladstone Bott’s mashie-shot, falling short, ran over the rough, peered for a moment into the depths to the left, then, winding up the path, trickled on to the green, struck a fortunate slope, acquired momentum, ran on, and dropped into the hole.

“Nearly missed it,” said Gladstone Bott, drawing a deep breath.

BRADBURY FISHER looked out upon a world that swam and danced before his eyes. He had not been prepared for this sort of thing. The way things were shaping, he felt that it would hardly surprise him now if the cups were to start jumping up and snapping at Bott’s ball like starving dogs.

“Three up,” said Gladstone Bott.

With a strong effort Bradbury Fisher mastered his feelings. His mouth set grimly. Matters, he perceived, had reached a crisis. He saw now that he had made a mistake in allowing himself to be intimidated by the importance of the occasion into being scientific. Nature had never intended him for a scientific golfer, and up till now he had been behaving like an animated illustration out of a book by Vardon. He had taken his club back along and near the turf, allowing it to trend around the legs as far as was permitted by the movement of the arms. He had kept his right elbow close to the side, this action coming into operation before the club was allowed to describe a section of a circle in an upward direction, whence it was carried by means of a slow, steady, swinging movement. He had pivoted, he had pronated the wrists, and he had been careful about the lateral hip-shift.

And it had all been wrong. That sort of stuff might suit some people, but not him. He was a biffer, a swatter, and a slosher; and it flashed upon him now that only by biffing, swatting, and sloshing as he had never biffed, swatted, and sloshed before could he hope to recover the ground he had lost.

Gladstone Bott was not one of those players who grow careless with success. His drive at the eighth was just as steady and short as ever. But this time Bradbury Fisher made no attempt to imitate him. For seven holes he had been checking his natural instincts, and now he drove with all the banked-up fury that comes with release from long suppression.

For an instant he remained poised on one leg like a stork; then there was a whistle and a crack, and the ball, smitten squarely in the midriff, flew down the course and, soaring over the bunkers, hit the turf and gambolled to within twenty yards of the green.

He straightened out the kinks in his spine with a grim smile. Allowing himself the regulation three putts, he would be down in five, and only a miracle could give Gladstone Bott anything better than a seven.

“Two down,” he said some minutes later, and Gladstone Bott nodded sullenly.

It was not often that Bradbury Fisher kept on the fairway with two consecutive drives, but strange things were happening to-day. Not only was his drive at the ninth a full two hundred and forty yards, but it was also perfectly straight.

“One down,” said Bradbury Fisher, and Bott nodded even more sullenly than before.

There are few things more demoralizing than to be consistently outdriven; and when he is outdriven by a hundred and seventy yards at two consecutive holes the bravest man is apt to be shaken. Gladstone Bott was only human. It was with a sinking heart that he watched his opponent heave and sway on the tenth tee: and when the ball once more flew straight and far down the course a strange weakness seemed to come over him. For the first time he lost his morale and topped. The ball trickled into the long grass, and after three fruitless stabs at it with a niblick he picked up, and the match was squared.

At the eleventh Bradbury Fisher also topped, and his tee-shot, though nice and straight, travelled only a couple of feet. He had to scramble to halve in eight.

The twelfth was another short hole; and Bradbury, unable to curb the fine, careless rapture which had crept into his game, had the misfortune to overshoot the green by some sixty yards, thus enabling his opponent to take the lead once more.

The thirteenth and fourteenth were halved, but Bradbury, driving another long ball, won the fifteenth, squaring the match.

IT seemed to Bradbury Fisher, as he took his stand on the sixteenth tee, that he now had the situation well in hand. At the thirteenth and fourteenth his drive had flickered, but on the fifteenth it had come back in all its glorious vigour and there appeared to be no reason to suppose that it had not come to stay. He recollected exactly how he had done that last colossal slosh, and he now prepared to reproduce the movements precisely as before. The great thing to remember was to hold the breath on the back-swing and not to release it before the moment of impact. Also, the eyes should not be closed until late in the down-swing. All great golfers have their little secrets, and that was Bradbury’s.

With these aids to success firmly fixed in his mind, Bradbury Fisher prepared to give the ball the nastiest bang that a golf-ball had ever had since Edward Blackwell was in his prime. He drew in his breath and, with lungs expanded to their fullest capacity, heaved back on to his large, flat right foot. Then, clenching his teeth, he lashed out.

When he opened his eyes, they fell upon a horrid spectacle. Either he had closed those eyes too soon or else he had breathed too precipitately—whatever the cause, the ball, which should have gone due south, was travelling with great speed sou’-sou’-east. And, even as he gazed, it curved to earth and fell into as uninviting a bit of rough as he had ever penetrated. And he was a man who had spent much time in many roughs.

LEAVING Gladstone Bott to continue his imitation of a spavined octogenarian rolling peanuts with a toothpick, Bradbury Fisher, followed by his caddie, set out on the long trail into the jungle.

Hope did not altogether desert him as he walked. In spite of its erratic direction, the ball had been so shrewdly smitten that it was not far from the green. Provided luck was with him and the lie not too desperate, a mashie would put him on the carpet. It was only when he reached the rough and saw what had happened that his heart sank. There the ball lay, half hidden in the grass, while above it waved the straggling tentacle of some tough-looking shrub. Behind it was a stone, and behind the stone, at just the elevation required to catch the back-swing of the club, was a tree. And, by an ironical stroke of fate which drew from Bradbury a hollow, bitter laugh, only a few feet to the right was a beautiful, smooth piece of turf from which it would have been a pleasure to play one’s second.

Dully Bradbury looked round to see how Bott was getting on. And then suddenly, as he found that Bott was completely invisible behind the belt of bushes through which he had just passed, a voice seemed to whisper to him, “Why not?”

Bradbury Fisher, remember, had spent thirty years in Wall Street.

It was at this moment that he realized that he was not alone. His caddie was standing at his side.

Bradbury Fisher gazed upon the caddie, whom until now he had not had any occasion to observe with any closeness.

The caddie was not a boy. He was a man, apparently in the middle forties, with bushy eyebrows and a walrus moustache; and there was something about his appearance which suggested to Bradbury that here was a kindred spirit. He reminded Bradbury a little of Spike Huggins, the safe-blower, who had been a member of his frat at Sing-Sing. It seemed to him that this caddie could be trusted in a delicate matter involving secrecy and silence. Had he been some babbling urchin, the risk might have been too great.

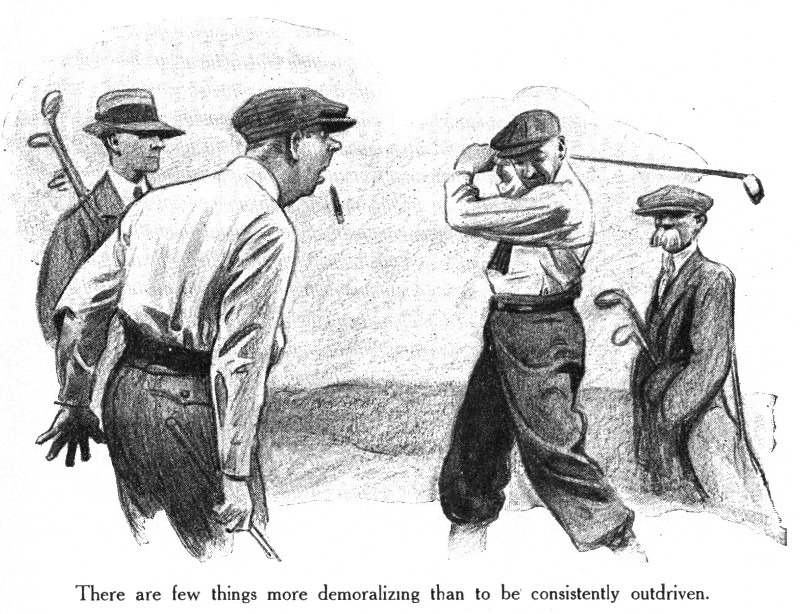

“Caddie,” said Bradbury.

“Sir?” said the caddie.

“Yours is an ill-paid job,” said Bradbury.

“It is, indeed, sir,” said the caddie.

“Would you like to earn fifty dollars?”

“Would you like to earn fifty dollars?”

“I would prefer to earn a hundred.”

“I meant a hundred,” said Bradbury.

He produced a roll of bills from his pocket, and peeled off one of that value. Then, stooping, he picked up his ball and placed it on the little oasis of turf. The caddie bowed intelligently.

“You mean to say,” cried Gladstone Bott a few moments later, “that you were out with your second? With your second!”

“I had a stroke of luck.”

“You’re sure it wasn’t about six strokes of luck?”

“My ball was right out in the open in an excellent lie.”

“Oh!” said Gladstone Bott, shortly.

“I have four for it, I think.”

“One down,” said Gladstone Bott.

“And two to play,” trilled Bradbury.

It was with a light heart that Bradbury Fisher teed up on the seventeenth. The match, he felt, was as good as over. The whole essence of golf is to discover a way of getting out of rough without losing strokes; and with this sensible, broad-minded man of the world caddying for him he seemed to have discovered the ideal way. It cost him scarcely a pang when he saw his drive slice away into a tangle of long grass, but for the sake of appearances he affected a little chagrin.

“Tut, tut!” he said.

“I shouldn’t worry,” said Gladstone Bott. “You will probably find it sitting up on an indiarubber tee which someone has dropped there.”

He spoke sardonically, and Bradbury did not like his manner. But then he never had liked Gladstone Bott’s manner, so what of that? He made his way to where the ball had fallen. It was lying under a bush.

“Caddie,” said Bradbury.

“Sir?” said the caddie.

“A hundred?”

“And fifty.”

“And fifty,” said Bradbury Fisher.

Gladstone Bott was still toiling along the fairway when Bradbury reached the green.

“How many?” he asked, eventually winning to the goal.

“On in two,” said Bradbury. “And you?”

“Playing seven.”

“Then let me see. If you take two putts, which is most unlikely, I shall have six for the hole and match.”

A minute later Bradbury had picked his ball out of the cup. He stood there, basking in the sunshine, his heart glowing with quiet happiness. It seemed to him that he had never seen the countryside looking so beautiful. The birds appeared to be singing as they had never sung before. The trees and the rolling turf had taken on a charm beyond anything he had ever encountered. Even Gladstone Bott looked almost bearable.

“A very pleasant match,” he said, cordially, “conducted throughout in the most sporting spirit. At one time I thought you were going to pull it off, old man, but there—class will tell.”

“I will now make my report,” said the caddie with the walrus moustache.

“Do so,” said Gladstone Bott, briefly.

Bradbury Fisher stared at the man with blanched cheeks. The sun had ceased to shine, the birds had stopped singing. The trees and the rolling turf looked pretty rotten, and Gladstone Bott perfectly foul. His heart was leaden with a hideous dread.

“Your report? Your—your report? What do you mean?”

“You don’t suppose,” said Gladstone Bott, “that I would play you an important match unless I had detectives watching you, do you? This gentleman is from the Quick Results Agency. What have you to report?” he said, turning to the caddie.

The caddie removed his bushy eyebrows, and with a quick gesture swept off his moustache.

“On the twelfth inst.,” he began in a monotonous, sing-song voice, “acting upon instructions received, I made my way to the Goldenville Golf Links in order to observe the movements of the man Fisher. I had adopted for the occasion the Number Three disguise and——”

“All right, all right,” said Gladstone Bott, impatiently. “You can skip all that. Come down to what happened at the sixteenth.”

The caddie looked wounded, but he bowed deferentially.

“At the sixteenth hole the man Fisher moved his ball into what—from his actions and furtive manner—I deduced to be a more favourable position.”

“Ah!” said Gladstone Bott.

“On the seventeenth the man Fisher picked up his ball and threw it with a movement of the wrist on to the green.”

“It’s a lie. A foul and contemptible lie,” shouted Bradbury Fisher.

“Realizing that the man Fisher might adopt this attitude, sir,” said the caddie, “I took the precaution of snapshotting him in the act with my miniature wrist-watch camera, the detective’s best friend.”

Bradbury Fisher covered his face with his hands and uttered a hollow groan.

“My match,” said Gladstone Bott, with vindictive triumph. “I’ll trouble you to deliver that butler to me f.o.b. at my residence not later than noon to-morrow. Oh, yes, and I was forgetting. You owe me three railroads.”

BLIZZARD, dignified but kindly, met Bradbury in the Byzantine hall on his return home.

“I trust your golf-match terminated satisfactorily, sir?” said the butler.

A pang, almost too poignant to be borne, shot through Bradbury.

“No, Blizzard,” he said. “No. Thank you for your kind inquiry, but I was not in luck.”

“Too bad, sir,” said Blizzard, sympathetically. “I trust the prize at stake was not excessive?”

“Well—er—well, it was rather big. I should like to speak to you about that a little later, Blizzard.”

“At any time that is suitable to you, sir. If you will ring for one of the assistant-underfootmen when you desire to see me, sir, he will find me in my pantry. Meanwhile, sir, this cable arrived for you a short while back.”

Bradbury took the envelope listlessly. He had been expecting a communication from his London agents announcing that they had bought Kent and Sussex, for which he had instructed them to make a firm offer just before he left England. No doubt this was their cable.

He opened the envelope, and started as if it had contained a scorpion. It was from his wife.

“Returning immediately ‘Aquitania,’ ” (it ran). “Docking Friday night. Meet without fail.”

Bradbury stared at the words, frozen to the marrow. Although he had been in a sort of trance ever since that dreadful moment on the seventeenth green, his great brain had not altogether ceased to function; and, while driving home in the car, he had sketched out roughly a plan of action which, he felt, might meet the crisis. Assuming that Mrs. Fisher was to remain abroad for another month, he had practically decided to buy a daily paper, insert in it a front-page story announcing the death of Blizzard, forward the clipping to his wife, and then sell his house and move to another neighbourhood. In this way it might be that she would never learn of what had occurred.

But if she was due back next Friday, the scheme fell through and exposure was inevitable.

He wondered dully what had caused her change of plans, and came to the conclusion that some feminine sixth sense must have warned her of peril threatening Blizzard. With a good deal of peevishness he wished that Providence had never endowed women with this sixth sense. A woman with merely five took quite enough handling.

“Sweet suffering soup-spoons!” groaned Bradbury.

“Sir?” said Blizzard.

“Nothing,” said Bradbury.

“Very good, sir,” said Blizzard.

FOR a man with anything on his mind, any little trouble calculated to affect the joie de vivre, there are few spots less cheering than the Customs sheds of New York. Draughts whistle dismally there—now to, now fro. Strange noises are heard. Customs officials chew gum and lurk grimly in the shadows like tigers awaiting the luncheon-gong. It is not surprising that Bradbury’s spirits, low when he reached the place, should have sunk to zero long before the gangplank was lowered and the passengers began to stream down it.

His wife was among the first to land. How beautiful she looked, thought Bradbury, as he watched her. And, alas, how intimidating. His tastes had always lain in the direction of spirited women. His first wife had been spirited. So had his second, third, and fourth. And the one at the moment holding office was perhaps the most spirited of the whole platoon. For one long instant, as he went to meet her, Bradbury Fisher was conscious of a regret that he had not married one of those meek, mild girls who suffer uncomplainingly at their husbands’ hands in the more hectic type of feminine novel. What he felt he could have done with at the moment was the sort of wife who thinks herself dashed lucky if the other half of the sketch does not drag her round the billiard-room by her hair, kicking her the while with spiked shoes.

Three conversational openings presented themselves to him as he approached her.

“Darling, there is something I want to tell you——”

“Dearest, I have a small confession to make——”

“Sweetheart, I don’t know if by any chance you remember Blizzard, our butler. Well, it’s like this——”

But, in the event, it was she who spoke first.

“Oh, Bradbury,” she cried, rushing into his arms, “I’ve done the most awful thing, and you must try to forgive me!”

Bradbury blinked. He had never seen her in this strange mood before. As she clung to him, she seemed timid, fluttering, and—although a woman who weighed a full hundred and fifty-seven pounds—almost fragile.

“What is it?” he inquired, tenderly. “Has somebody stolen your jewels?”

“No, no.”

“Have you been losing money at bridge?”

“No, no. Worse than that.”

Bradbury started.

“You didn’t sing ‘My Little Grey Home in the West’ at the ship’s concert?” he demanded, eyeing her closely.

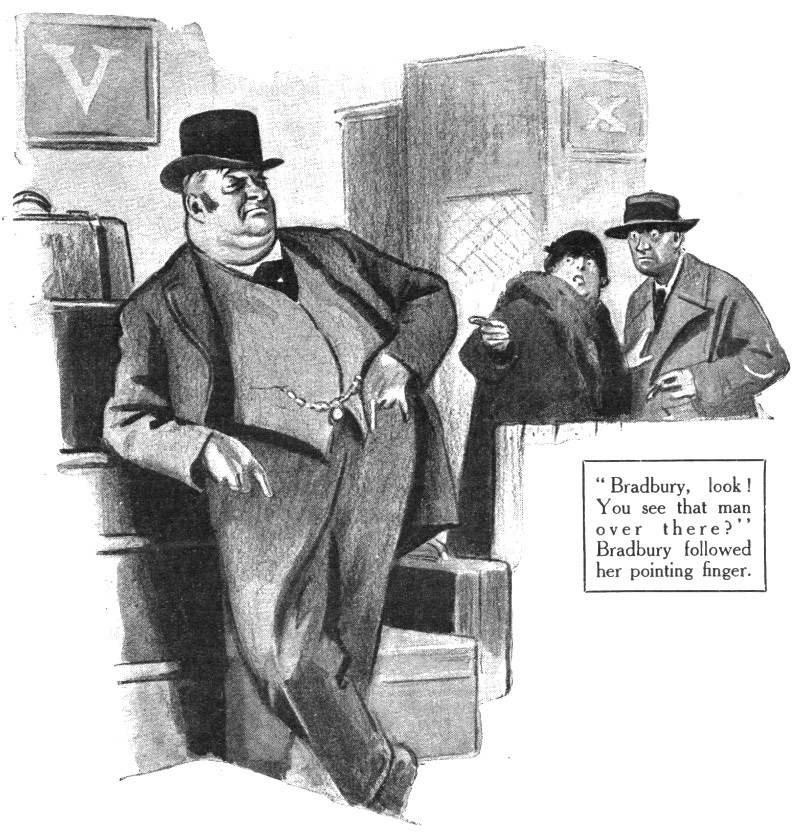

“No, no! Ah, how can I tell you? Bradbury, look! You see that man over there?”

Bradbury followed her pointing finger. Standing in an attitude of negligent dignity beside a pile of trunks under the letter V was a tall, stout, ambassadorial man, at the very sight of whom, even at this distance, Bradbury Fisher felt an odd sense of inferiority. His pendulous cheeks, his curving waistcoat, his protruding eyes, and the sequence of rolling chins combined to produce in Bradbury that instinctive feeling of being in the presence of a superior which we experience when meeting scratch golfers, head-waiters of fashionable restaurants, and traffic-policemen. A sudden pang of suspicion pierced him.

“Well?” he said, hoarsely. “What of him?”

“Bradbury, you must not judge me too harshly. We were thrown together and I was tempted——”

“Woman,” thundered Bradbury Fisher, “who is this man?”

“His name is Vosper.”

“And what is there between you and him, and when did it start, and why and how and where?”

Mrs. Fisher dabbed at her eyes with her handkerchief.

“It was at the Duke of Bootle’s, Bradbury. I was invited there for the weekend.”

“And this man was there?”

“Yes.”

“Ha! Proceed!”

“The moment I set eyes on him, something seemed to go all over me.”

“Indeed!”

“At first it was his mere appearance. I felt that I had dreamed of such a man all my life, and that for all these wasted years I had been putting up with the second-best.”

“Oh, you did, eh? Really? Is that so? You did, did you?” snorted Bradbury Fisher.

“I couldn’t help it, Bradbury. I know I have always seemed so devoted to Blizzard, and so I was. But, honestly, there is no comparison between them—really there isn’t. You should see the way Vosper stood behind the Duke’s chair. Like a high priest presiding over some mystic religious ceremony. And his voice when he asks you if you will have sherry or hock! Like the music of some wonderful organ. I couldn’t resist him. I approached him delicately, and found that he was willing to come to America. He had been eighteen years with the Duke, and he told me he couldn’t stand the sight of the back of his head any longer. So——”

Bradbury Fisher reeled.

“This man—this Vosper. Who is he?”

“Why, I’m telling you, honey. He was the Duke’s butler, and now he’s ours. Oh, you know how impulsive I am. Honestly, it wasn’t till we were half-way across the Atlantic that I suddenly said to myself, ‘What about Blizzard?’ What am I to do, Bradbury? I simply haven’t the nerve to fire Blizzard. And yet what will happen when he walks into his pantry and finds Vosper there? Oh, think, Bradbury, think!”

Bradbury Fisher was thinking—and for the first time in a week without agony.

“Evangeline,” he said, gravely, “this is awkward.”

“I know.”

“Extremely awkward.”

“I know, I know. But surely you can think of some way out of the muddle!”

“I may. I cannot promise, but I may.” He pondered deeply. “Ha! I have it! It is just possible that I may be able to induce Gladstone Bott to take on Blizzard.”

“Do you really think he would?”

“He may—if I play my cards carefully. At any rate, I will try to persuade him. For the moment you and Vosper had better remain in New York, while I go home and put the negotiations in train. If I am successful, I will let you know.”

“Do try your very hardest.”

“I think I shall be able to manage it. Gladstone and I are old friends, and he would stretch a point to oblige me. But let this be a lesson to you, Evangeline.”

“Oh, I will.”

“By the way,” said Bradbury Fisher, “I am cabling my London agents to-day to instruct them to buy J. H. Taylor’s shirt-stud for my collection.”

“Quite right, Bradbury, darling. And anything else you want in that way you will get, won’t you?”

“I will,” said Bradbury Fisher.

Notes:

Annotations to this story are in the end notes to the Saturday Evening Post version of the story.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums