The Strand Magazine, November 1928

THE day was so warm, so fair, so magically a thing of sunshine and blue skies and bird-song that anyone acquainted with Clarence, ninth Earl of Emsworth, and aware of his liking for fine weather would have pictured him going about the place on this summer morning with a beaming smile and an uplifted heart. Instead of which, humped over the breakfast table, he was directing at a blameless kippered herring a look of such intense bitterness that the fish seemed to sizzle beneath it. For it was August Bank Holiday, and Blandings Castle on August Bank Holiday became, in his lordship’s opinion, a miniature Inferno.

This was the day when his park and grounds broke out into a noisome rash of swings, roundabouts, marquees, toy balloons, and paper bags; when a tidal wave of the peasantry and its squealing young engulfed those haunts of immemorial peace. On August Bank Holiday he was not allowed to potter pleasantly about his gardens in an old coat; forces beyond his control shoved him into a stiff collar and a top-hat and told him to go out and be genial. And in the cool of the quiet evenfall they put him on a platform and made him make a speech. To a man with a day like that in front of him fine weather was a mockery.

His sister, Lady Constance Keeble, looked brightly at him over the coffee-pot.

“What a lovely morning!” she said.

Lord Emsworth’s gloom deepened. He chafed at being called upon—by this woman of all others—to behave as if everything was for the jolliest in the jolliest of all possible worlds. But for his sister Constance and her hawk-like vigilance, he might, he thought, have been able at least to dodge the top-hat.

“Have you got your speech ready?”

“Yes.”

“Well, mind you learn it by heart this time and don’t stammer and dodder as you did last year.”

Lord Emsworth pushed plate and kipper away. He had lost his desire for food.

“And don’t forget you have to go to the village this morning to judge the cottage gardens.”

“All right, all right, all right,” said his lordship testily. “I’ve not forgotten.”

“I think I will come to the village with you. There are a number of those Fresh Air London children staying there now, and I must warn them to behave properly when they come to the fête this afternoon. You know what London children are. McAllister says he found one of them in the gardens the other day, picking his flowers.”

At any other time the news of this outrage would, no doubt, have affected Lord Emsworth profoundly. But now, so intense was his self-pity, he did not even shudder. He drank coffee with the air of a man who regretted that it was not hemlock.

“By the way, McAllister was speaking to me again last night about that gravel path through the yew alley. He seems very keen on it.”

“Glug!” said Lord Emsworth—which, as any philologist will tell you, is the sound which peers of the realm make when stricken to the soul while drinking coffee.

CONCERNING Glasgow, that great commercial and manufacturing city in the county of Lanarkshire in Scotland, much has been written. So lyrically does the Encyclopædia Britannica deal with the place that it covers twenty-seven pages before it can tear itself away and go on to Glass, Glastonbury, Glatz, and Glauber. The only aspect of it, however, which immediately concerns the present historian is the fact that the citizens it breeds are apt to be grim, dour, persevering, tenacious men; men with red whiskers who know what they want and mean to get it. Such a one was Angus McAllister, head-gardener at Blandings Castle.

For years Angus McAllister had set before himself as his earthly goal the construction of a gravel path through the Castle’s famous yew alley. For years he had been bringing the project to the notice of his employer, though in anyone less whiskered the latter’s unconcealed loathing would have caused embarrassment. And now, it seemed, he was at it again.

“Gravel path!” Lord Emsworth stiffened through the whole length of his stringy body. Nature, he had always maintained, intended a yew alley to be carpeted with a mossy growth. And, whatever Nature felt about it, he personally was dashed if he was going to have men with Clydeside accents and faces like dissipated potatoes coming along and mutilating that lovely expanse of green velvet. “Gravel path, indeed! Why not asphalt? Why not a few hoardings with advertisements of liver pills and a filling station? That’s what the man would really like.”

Lord Emsworth felt bitter, and when he felt bitter he could be terribly sarcastic.

“Well, I think it is a very good idea,” said his sister. “One could walk there in wet weather then. Damp moss is ruinous to shoes.”

Lord Emsworth rose. He could bear no more of this. He left the table, the room, and the house, and, reaching the yew alley some minutes later, was revolted to find it infested by Angus McAllister in person. The head-gardener was standing gazing at the moss like a high priest of some ancient religion about to stick the gaff into the human sacrifice.

Lord Emsworth rose. He could bear no more of this. He left the table, the room, and the house, and, reaching the yew alley some minutes later, was revolted to find it infested by Angus McAllister in person. The head-gardener was standing gazing at the moss like a high priest of some ancient religion about to stick the gaff into the human sacrifice.

“Morning, McAllister,” said Lord Emsworth, coldly.

“Good morrrrning, your lorrudsheep.”

There was a pause. Angus McAllister, extending a foot that looked like a violin-case, pressed it on the moss. The meaning of the gesture was plain. It expressed contempt, dislike, a generally anti-moss spirit; and Lord Emsworth, wincing, surveyed the man unpleasantly through his pince-nez. Though not often given to theological speculation, he was wondering why Providence, if obliged to make head-gardeners, had found it necessary to make them so Scotch. In the case of Angus McAllister, why, going a step farther, have made him a human being at all? All the ingredients of a first-class mule simply thrown away. He felt that he might have liked Angus McAllister if he had been a mule.

“I was speaking to her leddyship yesterday.”

“Oh?”

“About the gravel path I was speaking to her leddyship.”

“Oh?”

“Her leddyship likes the notion fine.”

“Indeed! Well——”

Lord Emsworth’s face had turned a lively pink, and he was about to release the blistering words which were forming themselves in his mind when suddenly he caught the head-gardener’s eye and paused. Angus McAllister was looking at him in a peculiar manner, and he knew what that look meant. Just one crack, his eye was saying—in Scotch, of course—just one crack out of you and I tender my resignation. And with a sickening shock it came home to Lord Emsworth how completely he was in this man’s clutches.

He shuffled miserably. Yes, he was helpless. Except for that kink about gravel paths, Angus McAllister was a head-gardener in a thousand, and he needed him. He could not do without him. Filled with the coward rage that dares to burn but does not dare to blaze, Lord Emsworth coughed a cough that was undisguisedly a bronchial white flag.

“I’ll—er—I’ll think it over, McAllister.”

“Mphm.”

“I have to go to the village now. I will see you later.”

“Mphm.”

“Meanwhile, I will—er—think it over.”

“Mphm.”

THE task of judging the floral displays in the cottage gardens of the little village of Blandings Parva was one to which Lord Emsworth had looked forward with pleasurable anticipation. It was the sort of job he liked. But now, even though he had managed to give his sister Constance the slip and was free from her threatened society, he approached the task with a downcast spirit. It is always unpleasant for a proud man to realize that he is no longer captain of his soul; that he is to all intents and purposes ground beneath the number twelve heel of a Glaswegian head-gardener; and, brooding on this, he judged the cottage gardens with a distrait eye. It was only when he came to the last on his list that anything like animation crept into his demeanour.

This, he perceived, peering over its rickety fence, was not at all a bad little garden. It demanded closer inspection. He unlatched the gate and pottered in. And a dog, dozing behind a water-butt, opened one eye and looked at him. It was one of those hairy, nondescript dogs, and its gaze was cold, wary, and suspicious, like that of a stockbroker who thinks someone is going to play the confidence trick on him.

Lord Emsworth did not observe the animal. He had pottered to a bed of wallflowers and now, stooping, he took a sniff at them.

As sniffs go, it was an innocent sniff, but the dog for some reason appeared to read into it criminality of a high order. All the indignant householder in him woke in a flash. The next moment the world had become full of hideous noises, and Lord Emsworth’s preoccupation was swept away in a passionate desire to save his ankles from harm.

He was not at his best with strange dogs. Beyond saying “Go away, sir!” and leaping to and fro with an agility surprising in one of his years, he had accomplished little in the direction of a reasoned plan of defence when the cottage door opened and a girl came out.

“Hoy!” cried the girl.

And on the instant, at the mere sound of her voice, the mongrel, suspending hostilities, bounded at the new-comer and writhed on his back at her feet with all four legs in the air. The spectacle reminded Lord Emsworth irresistibly of his own behaviour when in the presence of Angus McAllister.

He blinked at his preserver. She was a small girl, of uncertain age—possibly twelve or thirteen, though a combination of London fogs and early cares had given her face a sort of wizened motherliness which in some odd way caused his lordship from the first to look on her as belonging to his own generation. She was the type of girl you see in back streets carrying a baby nearly as large as herself and still retaining sufficient energy to lead one little brother by the hand and shout recrimination at another in the distance. Her cheeks shone from recent soaping, and she was dressed in a velveteen frock which was obviously the pick of her wardrobe. Her hair, in defiance of the prevailing mode, she wore drawn tightly back into a short pigtail.

“Er—thank you,” said Lord Emsworth.

“Thank you, sir,” said the girl.

For what she was thanking him, his lordship was not able to gather. Later, as their acquaintance ripened, he was to discover that this strange gratitude was a habit with his new friend. She thanked everybody for everything. At the moment, the mannerism surprised him. He continued to blink at her through his pince-nez.

Lack of practice had rendered Lord Emsworth a little rusty in the art of making conversation to members of the other sex. He sought in his mind for topics.

“Fine day.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“Are you——” Lord Emsworth furtively consulted his list. “Are you the daughter of—ah—Ebenezer Sprockett?” he asked, thinking, as he had often thought before, what ghastly names some of his tenantry possessed.

“No, sir. I’m from London, sir.”

“No, sir. I’m from London, sir.”

“Ah! London, eh? Doosid warm it must be there.” He paused. Then, remembering a formula of his youth, “Er—been out much this season?”

“No, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“Everybody out of town now, I suppose? What part of London?”

“Drury Line, sir.”

“What’s your name, eh, what?”

“Gladys, sir. Thank you, sir. This is Ern.”

A small boy had wandered out of the cottage, a rather hard-boiled specimen with freckles, bearing surprisingly in his hand a large and beautiful bunch of flowers. Lord Emsworth bowed courteously, and with the addition of this third party to the tête-à-tête felt more at his ease.

“How do you do?” he said. “What pretty flowers!”

With her brother’s advent, Gladys also had lost diffidence and gained conversational aplomb.

“A treat, ain’t they?” she agreed eagerly. “I got ’em for ’im up at the big ’ahse. Coo! The old josser the plice belongs to didn’t ’arf chase me. ’E found me picking ’em and ’e sharted somefin’ at me and come runnin’ after me, but I copped ’im on the shin wiv a stone and ’e stopped to rub it and I come away.”

LORD EMSWORTH might have corrected her impression that Blandings Castle and its gardens belonged to Angus McAllister, but his mind was so filled with admiration and gratitude that he refrained from doing so. He looked at the girl almost reverently. Not content with controlling savage dogs with a mere word, this super-woman actually threw stones at Angus McAllister—a thing which he had never been able to nerve himself to do in an association which had lasted nine years—and, what was more, copped him on the shin with them. What nonsense, Lord Emsworth felt, the papers talked about the modern girl. If this was a specimen, the modern girl was the highest point the sex had yet reached.

“Ern,” said Gladys, changing the subject, “is wearin’ ’air-oil to-diy.”

Lord Emsworth had already observed this and had, indeed, been moving to windward as she spoke.

“For the feet,” explained Gladys.

“For the feet?” It seemed unusual.

“For the feet in the pork this afternoon.”

“Oh, you are going to the fête?”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

For the first time Lord Emsworth found himself regarding that grisly social event with something approaching favour.

“We must look out for one another there,” he said, cordially. “You will remember me again? I shall be wearing——” he gulped—“a top-hat.”

“Ern’s going to wear a stror penamar that’s been give ’im.”

Lord Emsworth regarded the lucky young devil with frank envy. He rather fancied he knew that panama. It had been his constant companion for some six years, and then had been torn from him by his sister Constance and handed over to the vicar’s wife for her rummage-sale.

He sighed.

“Well, good-bye.”

“Good-bye, sir. Thank you, sir.”

Lord Emsworth walked pensively out of the garden and, turning into the little street, encountered Lady Constance.

“Oh, there you are, Clarence.”

“Yes,” said Lord Emsworth, for such was the case.

“Have you finished judging the gardens?”

“Yes.”

“I am just going into this end cottage here. The vicar tells me there is a little girl from London staying there. I want to warn her to behave this afternoon. I have spoken to the others.”

Lord Emsworth drew himself up. His pince-nez were slightly askew, but despite this his gaze was commanding and impressive.

“Well, mind what you say,” he said, authoritatively. “None of your district visiting stuff, Constance.”

“What do you mean?”

“You know what I mean. I have the greatest respect for the young lady to whom you refer. She behaved on a certain recent occasion—on two recent occasions—with notable gallantry and resource, and I won’t have her ballyragged, understand that!”

THE technical title of the orgy which broke out annually on the first Monday in August in the park of Blandings Castle was the Blandings Parva School Treat, and it seemed to Lord Emsworth, wanly watching the proceedings from under the shadow of his top-hat, that if this was the sort of thing schools looked on as pleasure he and they were mentally poles apart. A function like the Blandings Parva School Treat blurred his conception of Man as Nature’s final word.

The decent sheep and cattle to whom this park normally belonged had been hustled away into regions unknown, leaving the smooth expanse of turf to children whose vivacity scared Lord Emsworth and adults who appeared to him to have cast aside all dignity and every other noble quality which goes to make a one hundred per cent. British citizen. Look at Mrs. Rossiter over there, for instance, the wife of Jno. Rossiter, Provisions, Groceries, and Home-Made Jams. On any other day of the year, when you met Mrs. Rossiter, she was a nice, quiet, docile woman who gave at the knees respectfully as you passed. To-day, flushed in the face and with her bonnet on one side, she seemed to have gone completely native. She was wandering to and fro drinking lemonade out of a bottle and employing her mouth, when not so occupied, to make a devastating noise with what he believed was termed a squeaker.

The injustice of the thing stung Lord Emsworth. This park was his own private park. What right had people to come and blow squeakers in it? How would Mrs. Rossiter like it if one afternoon he suddenly invaded her neat little garden in the High Street and rushed about over her lawn blowing a squeaker? And it was always on these occasions so infernally hot. July might have ended in a flurry of snow, but directly the first Monday in August arrived and he had to put on a stiff collar out came the sun, blazing with tropic fury.

Of course, admitted Lord Emsworth, for he was a fair-minded man, this cut both ways. The hotter the day, the more quickly his collar lost its starch and ceased to spike him like a javelin. This afternoon, for instance, it had resolved itself almost immediately into something which felt like a wet compress. Severe as were his sufferings, he was compelled to recognize that he was that much ahead of the game.

A masterful figure loomed at his side.

“Clarence!”

Lord Emsworth’s mental and spiritual state was now such that not even the advent of his sister Constance could add noticeably to his discomfort.

“Clarence, you look a perfect sight.”

“I know I do. Who wouldn’t in a rig-out like this? Why in the name of goodness you always insist——”

“Please don’t be childish, Clarence. I cannot understand the fuss you make about dressing for once in your life like a reasonable English gentleman and not like a tramp.”

“It’s this top-hat. It’s exciting the children.”

“What on earth do you mean, exciting the children?”

“Well, all I can tell you is that just now, as I was passing the place where they’re playing football—football! In weather like this!—a small boy called out something derogatory and threw a portion of a coco-nut at it.”

“If you will identify the child,” said Lady Constance, warmly, “I will have him severely punished.”

“How the dickens,” replied his lordship with equal warmth, “can I identify the child? They all look alike to me. And if I did identify him, I would shake him by the hand. A boy who throws coco-nuts at top-hats is fundamentally sound in his views. And stiff collars——”

“Stiff! That’s what I came to speak to you about. Are you aware that your collar looks like a rag? Go in and change it at once.”

“But, my dear Constance——”

“At once, Clarence. I simply cannot understand a man having so little pride in his appearance. But all your life you have been like that. I remember when we were children——”

Lord Emsworth’s past was not of such a purity that he was prepared to stand and listen to it being lectured on by a sister with a good memory.

“Oh, all right, all right, all right,” he said. “I’ll change it. I’ll change it.”

“Well, hurry. They are just starting tea.”

Lord Emsworth quivered.

“Have I got to go into that tea-tent?”

“Of course you have. Don’t be so ridiculous. I do wish you would realize your position. As master of Blandings Castle——”

A bitter, mirthless laugh from the poor peon thus ludicrously described drowned the rest of the sentence.

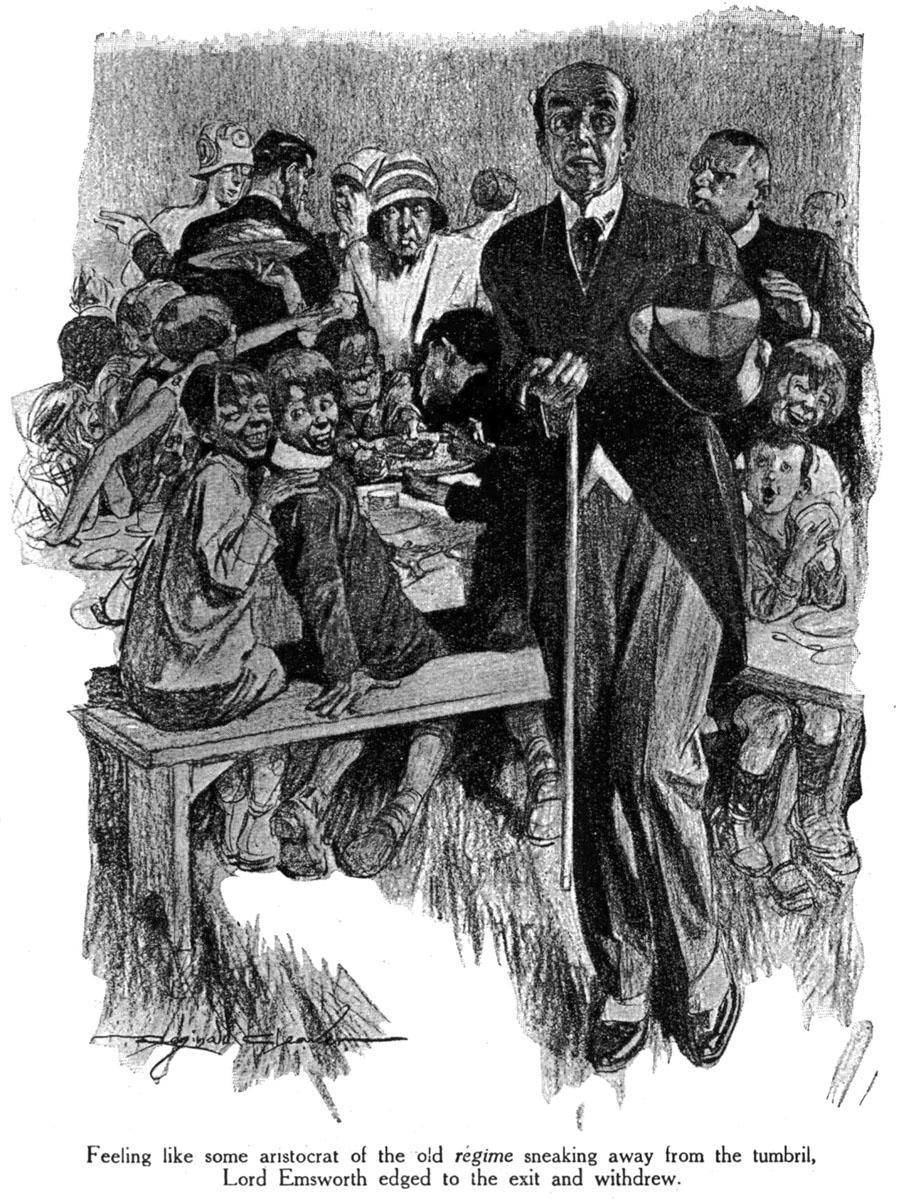

IT always seemed to Lord Emsworth, in analysing these entertainments, that the August Bank Holiday saturnalia at Blandings Castle reached a peak of repulsiveness when tea was served in the big marquee. Tea over, the agony abated, to become acute once more at the moment when he stepped to the edge of the platform and cleared his throat and tried to recollect what the deuce he had planned to say to the goggling audience beneath him. After that it subsided again and passed until the following August.

Conditions during the tea hour, the marquee having stood all day under a blazing sun, were generally such that Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, had they been there, could have learned something new about burning fiery furnaces. Lord Emsworth, delayed by the revision of his toilet, made his entry when the meal was half over and was pleased to find that his second collar almost instantaneously began to relax its iron grip. That, however, was the only gleam of happiness which was to be vouchsafed him. Once in the tent, it took him but a moment to discern with his experienced eye that the present feast was eclipsing in frightfulness all its predecessors.

Young Blandings Parva, in its normal form, tended rather to the stolidly bovine than the riotous. In all villages, of course, there must of necessity be an occasional tough egg—in the case of Blandings Parva the names of Willie Drake and Thomas (Rat-Face) Blenkiron spring to the mind—but it was seldom that the local infants offered anything beyond the power of a curate to control. What was giving the present gathering its striking resemblance to a lively reunion of sans-culottes at the height of the French Revolution was the admixture of the Fresh Air London visitors.

About the London child, reared among the tin cans and cabbage stalks of Drury Lane and Clare Market, there is a breezy insouciance which his country cousin lacks. Years of back-chat with annoyed parents and relatives have cured him of any tendency he may have had towards shyness, with the result that when he requires anything he grabs for it, and when he is amused by any slight peculiarity in the personal appearance of members of the governing classes he finds no difficulty in translating his thoughts into speech. Already, up and down the long tables, the curate’s unfortunate squint was coming in for hearty comment, and the front teeth of one of the school-teachers ran it a close second for popularity. Lord Emsworth was not, as a rule, a man of swift inspirations, but it occurred to him at this juncture that it would be a prudent move to take off his top-hat before his little guests observed it and appreciated its humorous possibilities.

Lord Emsworth had had sufficient. Even Constance, unreasonable woman though she was, could hardly expect him to stay and beam genially under conditions like this. All civilized laws had obviously gone by the board and anarchy reigned in the marquee. The curate was doing his best to form a provisional government consisting of himself and the two school-teachers, but there was only one man who could have coped adequately with the situation, and that was King Herod, who—regrettably—was not among those present. Feeling like some aristocrat of the old régime sneaking away from the tumbril, Lord Emsworth edged to the exit and withdrew.

OUTSIDE the marquee the world was quieter, but only comparatively so. What Lord Emsworth craved was solitude, and in all the broad park there seemed to be but one spot where it was to be had. This was a red-tiled shed, standing beside a small pond, used at happier times as a lounge or retiring-room for cattle. Hurrying thither, his lordship had just begun to revel in the cool, cow-scented dimness of its interior when from one of the dark corners, causing him to start and bite his tongue, there came the sound of a subdued sniff.

He turned. This, he felt, was persecution. With the whole park to mess about in, why should an infernal child invade this one sanctuary of his? He spoke with angry sharpness. He came of a line of warrior ancestors and his fighting blood was up.

“Who’s that?”

“Me, sir. Thank you, sir.”

Only one person of Lord Emsworth’s acquaintance was capable of expressing gratitude for having been barked at in such a tone. His wrath died away and remorse took its place. He felt like a man who in error has kicked a favourite dog.

“God bless my soul!” he exclaimed. “What in the world are you doing in a cowshed?”

“I was put.”

“Put? How do you mean, put? Why?”

“For pinching things, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“Eh? What? Pinching things? Most extraordinary. What did you—er—pinch?”

“Two buns, two jem-sengwiches, two apples, and a slicer cake.”

The girl had come out of her corner and was standing correctly at attention. Force of habit had caused her to intone the list of the purloined articles in the sing-song voice in which she was wont to recite the multiplication-table at school, but Lord Emsworth could see that she was deeply moved. Tear-stains glistened on her face, and no Emsworth had ever been able to watch unstirred a woman’s tears. The ninth Earl was visibly affected.

“Blow your nose,” he said, hospitably extending his handkerchief.

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“What did you say you had pinched? Two buns——”

“——Two jem-sengwiches, two apples, and a slicer cake.”

“Did you eat them?”

“No, sir. They wasn’t for me. They was for Ern.”

“Ern? Oh, ah, yes. Yes, to be sure. For Ern, eh?”

“Yes, sir.”

“But why the dooce couldn’t Ern have—er—pinched them for himself? Strong, able-bodied young feller, I mean.”

Lord Emsworth, a member of the old school, did not like this disposition on the part of the modern young man to shirk the dirty work and let the woman pay.

“Ern wasn’t allowed to come to the treat, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“What! Not allowed? Who said he mustn’t?”

“The lidy, sir.”

“What lidy?”

“The one that come in just after you’d gorn this morning.”

A fierce snort escaped Lord Emsworth. Constance! What the devil did Constance mean by taking it upon herself to revise his list of guests without so much as a—— Constance, eh? He snorted again. One of these days Constance would go too far.

“Monstrous!” he cried.

“Yes, sir.”

“High-handed tyranny, by Gad. Did she give any reason?”

“The lidy didn’t like Ern biting ’er in the leg, sir.”

“Ern bit her in the leg?”

“Yes, sir. Pliying ’e was a dorg. And the lidy was cross and Ern wasn’t allowed to come to the treat, and I told ’im I’d bring ’im back somefing nice.”

Lord Emsworth breathed heavily. He had not supposed that in these degenerate days a family like this existed. The sister copped Angus McAllister on the shin with stones, the brother bit Constance in the leg. It was like listening to some grand old saga of the exploits of heroes and demi-gods.

“I thought if I didn’t ’ave nothing myself it would make it all right.”

“Nothing?” Lord Emsworth started. “Do you mean to tell me you have not had tea?”

“No, sir. Thank you, sir. I thought if I didn’t ’ave none, then it would be all right Ern ’aving what I would ’ave ’ad if I ’ad ’ave ’ad.”

His lordship’s head, never strong, swam a little. Then it resumed its equilibrium. He caught her drift.

“God bless my soul!” said Lord Emsworth. “I never heard anything so monstrous and appalling in my life. Come with me.”

“The lidy said I was to stop ’ere, sir.”

Lord Emsworth gave vent to his loudest snort of the afternoon.

“Confound the lidy!”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

FIVE minutes later, Beach, the butler, enjoying a siesta in the housekeeper’s room, was roused from his slumbers by the unexpected ringing of a bell. Answering its summons, he found his employer in the library, and with him a surprising young person in a velveteen frock, at the sight of whom his eyebrows quivered and, but for his iron self-restraint, would have risen.

“Beach!”

“Your lordship?”

“This young lady would like some tea.”

“Very good, your lordship.”

“Buns, you know. And apples, and jam-sandwiches, and cake and that sort of thing.”

“Very good, your lordship.”

“And she has a brother, Beach.”

“Indeed, your lordship?”

“She will want to take some stuff away for him.” Lord Emsworth turned to his guest. “Ernest would like a little chicken, perhaps?”

“Coo!”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“And a slice or two of ham?”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“And—Ernest has no gouty tendency?”

“No, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“Capital! Then a bottle of that new lot of port, Beach. It’s some stuff they’ve sent me down to try,” explained his lordship. “Nothing special, you understand,” he added, apologetically, “but quite drinkable. I should like your brother’s opinion of it. See that all that is put together in a parcel, Beach, and leave it on the table in the hall. We will pick it up as we go out.”

A welcome coolness had crept into the evening air by the time Lord Emsworth and his guest came out of the great door of the castle. Gladys, holding her host’s hand and clutching the parcel, sighed contentedly. She had done herself well at the tea-table. Life seemed to have nothing more to offer.

Lord Emsworth did not share this view. His spacious mood had not yet exhausted itself.

“Now, is there anything else you can think of that Ernest would like?” he asked. “If so, do not hesitate to mention it. Beach, can you think of anything?”

The butler, hovering respectfully, was unable to do so.

“No, your lordship. I ventured to add—on my own responsibility, your lordship—some hard-boiled eggs and a pot of jam to the parcel.”

“Excellent! You are sure there is nothing else?”

A wistful look came into Gladys’s eyes.

“Could he ’ave some flarce?”

“Certainly,” said Lord Emsworth. “Certainly, certainly, certainly. By all means. Just what I was about to suggest my—— Er—what is flarce?”

Beach, the linguist, interpreted.

“I think the young lady means flowers, your lordship.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir. Flarce.”

“Oh!” said Lord Emsworth. “Oh! Flarce?” he said, slowly. “Oh, ah, yes. Yes, I see. H’m!”

He removed his pince-nez, wiped them thoughtfully, replaced them, and gazed with wrinkling forehead at the gardens that stretched gaily out before him. Flarce! It would be idle to deny that those gardens contained flarce in full measure. They were bright with Achillea, Bignonia Radicans, Campanula, Digitalis, Euphorbia, Funkia, Gypsophila, Helianthus, Iris, Liatris, Monarda, Phlox Drummondi, Salvia, Thalictrum, Vinca, and Yucca. But the devil of it was that Angus McAllister would have a fit if they were picked. Across the threshold of this Eden the ginger whiskers of Angus McAllister lay like the flaming sword.

AS a general rule, the procedure for getting flowers out of Angus McAllister was as follows. You waited till he was in one of his rare moods of complaisance, then you led the conversation gently round to the subject of interior decoration, and then, choosing your moment, you asked if he could possibly spare a few to be put in vases. The last thing you thought of doing was to charge in and start helping yourself.

“I—er——” said Lord Emsworth.

He stopped. In a sudden blinding flash of clear vision he had seen himself for what he was—the spineless, unspeakably unworthy descendant of ancestors who, though they may have had their faults, had certainly known how to handle employés. It was: “How now, varlet!” and “Marry come up, thou malapert knave!” in the days of previous Earls of Emsworth. Of course, they had possessed certain advantages which he lacked. It undoubtedly helped a man in his dealings with the domestic staff to have, as they had had, the rights of the high, the middle, and the low justice—which meant, broadly, that if you got annoyed with your head-gardener you could immediately divide him into four head-gardeners with a battle-axe and no questions asked; but even so, he realized that they were better men than he was and that, if he allowed craven fear of Angus McAllister to stand in the way of this delightful girl and her charming brother getting all the flowers they required, he was not worthy to be the last of their line.

Lord Emsworth wrestled with his tremors.

“Certainly, certainly, certainly,” he said, though not without a qualm; “take as many as you want.”

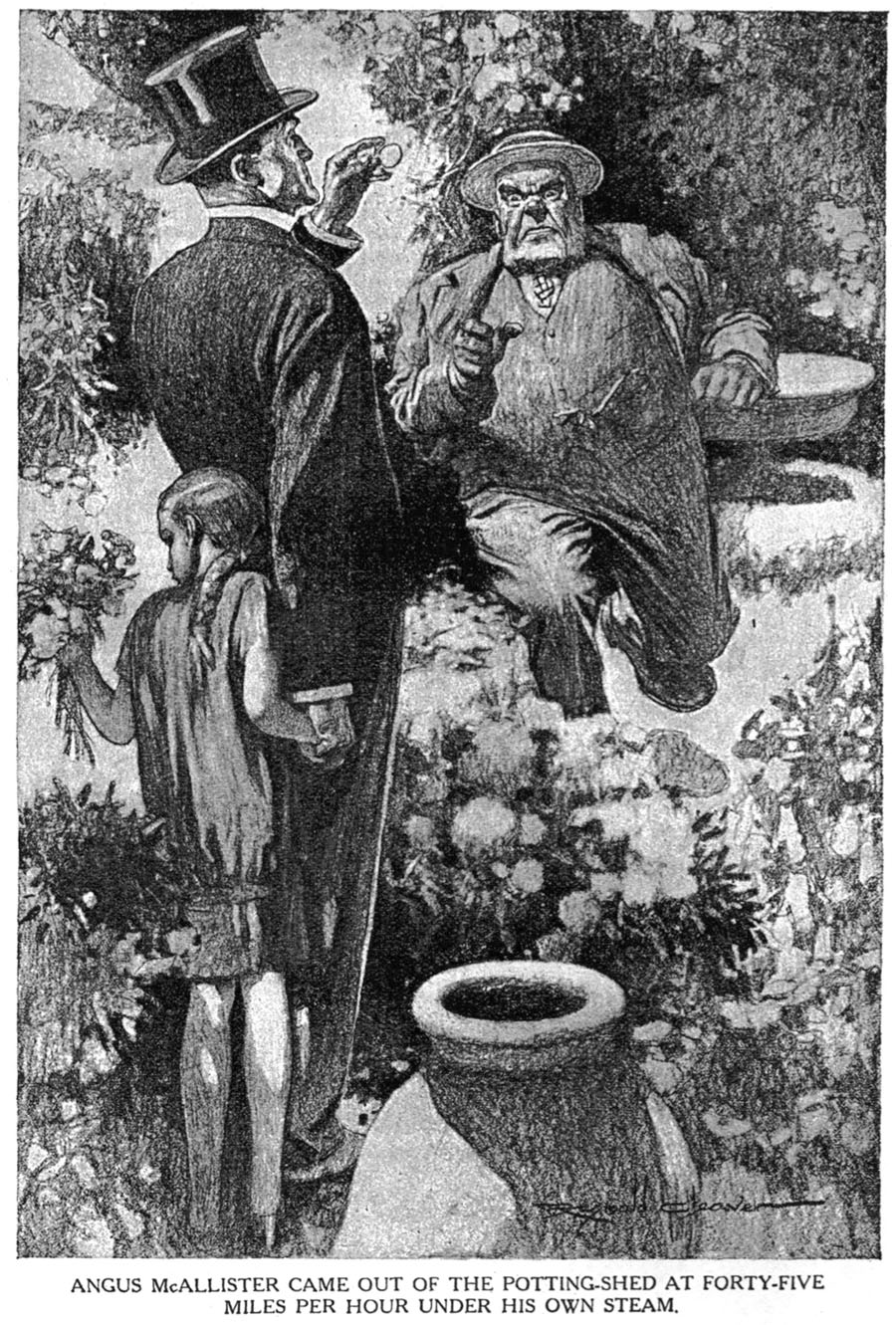

And so it came about that Angus McAllister, crouched in his potting-shed like some dangerous beast in its den, beheld a sight which first froze his blood and then sent it boiling through his veins. Flitting to and fro through his sacred gardens, picking his sacred flowers, was a small girl in a velveteen frock. And—which brought apoplexy a step closer—it was the same small girl who two days before had copped him on the shin with a stone. The stillness of the summer evening was shattered by a roar that sounded like boilers exploding, and Angus McAllister came out of the potting-shed at forty-five miles per hour under his own steam.

Gladys did not linger. She was a London child, trained from infancy to bear herself gallantly in the presence of alarms and excursions, but this excursion had been so sudden that it momentarily broke her nerve. With a horrified yelp, she scuttled to where Lord Emsworth stood and, hiding behind him, clutched the tails of his morning-coat.

“Oo-er!” said Gladys.

Lord Emsworth was not feeling so frightfully good himself. We have pictured him a few moments back drawing inspiration from the nobility of his ancestors and saying, in effect, “That for McAllister!” but truth now compels us to admit that this hardy attitude was largely due to the fact that he believed the head-gardener to be a safe quarter of a mile away among the swings and roundabouts of the fête. The spectacle of the man charging vengefully down on him with gleaming eyes and bristling whiskers made him feel like a nervous English infantryman at the Battle of Bannockburn. His knees shook and the soul within him quivered.

And then something happened, and the whole aspect of the situation changed.

It was, in itself, quite a trivial thing, but it had an astoundingly stimulating effect on Lord Emsworth’s morale. What happened was that Gladys, seeking further protection, slipped at this moment a small, hot hand into his.

It was a mute vote of confidence, and Lord Emsworth intended to be worthy of it.

“He’s coming,” whispered his lordship’s inferiority complex, agitatedly.

“What of it?” replied Lord Emsworth, stoutly.

“Tick him off,” breathed his lordship’s ancestors in his other ear.

“Leave it to me,” replied Lord Emsworth.

He drew himself up and adjusted his pince-nez. He felt filled with a cool masterfulness. If the man tendered his resignation, let him tender his damned resignation. There were other head-gardeners in the world.

“Well, McAllister?” said Lord Emsworth, coldly.

He removed his top-hat and brushed it against his sleeve.

“What is the matter, McAllister?”

He replaced his top-hat.

“You appear agitated, McAllister.”

He jerked his head militantly. The hat fell off. He let it lie. Freed from its loathsome weight, he felt more masterful than ever. It had just needed that to bring him to the top of his form.

“This young lady,” said Lord Emsworth, “has my full permission to pick all the flowers she wants, McAllister. If you do not see eye to eye with me in this matter, McAllister, say so and we will discuss what you are going to do about it, McAllister. These gardens, McAllister, belong to me, and if you do not—er—appreciate that fact you will, no doubt, be able to find another employer—ah—more in tune with your views. I value your services highly, McAllister, but I will not be dictated to in my own garden, McAllister. Er—dash it,” added his lordship, spoiling the whole effect.

A LONG moment followed in which Nature stood still, breathless. The Achillea stood still. So did the Bignonia radicans. So did the Campanula, the Digitalis, the Euphorbia, the Funkia, the Gypsophila, the Helianthus, the Iris, the Liatris, the Monarda, the Phlox drummondii, the Salvia, the Thalictrum, the Vinca, and the Yucca. From far off in the direction of the park there sounded the happy howls of children who were probably breaking things, but even these seemed hushed. The evening breeze had died away.

Angus McAllister stood glowering. His attitude was that of one sorely perplexed. So might the early bird have looked if the worm earmarked for its breakfast had suddenly turned and snapped at it. It had never occurred to him that his employer would voluntarily suggest that he sought another position, and now that he had suggested it Angus McAllister disliked the idea very much. Blandings Castle was in his bones. Elsewhere he would feel an exile. He fingered his whiskers, but they gave him no comfort.

He made his decision. Better to cease to be a Napoleon than be a Napoleon in exile.

“Mphm,” said Angus McAllister.

“Oh, and by the way, McAllister,” said Lord Emsworth, “that matter of the gravel path through the yew alley. I’ve been thinking it over, and I won’t have it. Not on any account. Mutilate my beautiful moss with a beastly gravel path? Make an eyesore of the loveliest spot in one of the finest and oldest gardens in the United Kingdom? Certainly not. Most decidedly not. Try to remember, McAllister, as you work in the gardens of Blandings Castle, that you are not back in Glasgow, laying out recreation grounds. That is all, McAllister. Er—dash it—that is all.”

“Mphm,” said Angus McAllister.

He turned. He walked away. The potting-shed swallowed him up. Nature resumed its breathing. The breeze began to blow again. And all over the gardens birds who had stopped on their high note carried on according to plan.

Lord Emsworth took out his handkerchief and dabbed with it at his forehead. He was shaken, but a novel sense of being a man among men thrilled him. It might seem bravado, but he wished—yes, dash it, he almost wished—that his sister Constance would come along and start something while he felt like this.

He had his wish.

“Clarence!”

Yes, there she was, hurrying towards him up the garden path. She, like McAllister, seemed agitated. Something was on her mind.

“Clarence!”

“Don’t keep saying ‘Clarence!’ as if you were a dashed parrot,” said Lord Emsworth, haughtily. “What the dickens is the matter, Constance?”

“Matter? Do you know what the time is? Do you know that everybody is waiting down there for you to make your speech?”

Lord Emsworth met her eye sternly.

“I do not,” he said. “And I don’t care. I’m not going to make any dashed speech. If you want a speech, let the vicar make it. Or make it yourself. Speech! I never heard such dashed nonsense in my life.” He turned to Gladys. “Now, my dear,” he said, “if you will just give me time to get out of these infernal clothes and this ghastly collar and put on something human, we’ll go down the village and have a chat with Ern.”

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine had Bignonia Radicans (twice); corrected to Bignonia radicans

Magazine had Phlox Drummondi (twice); corrected to Phlox drummondii

Annotations to this story as it appeared in book form are in the notes to Blandings Castle and Elsewhere on this site.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums