The Strand Magazine, July 1928

“ RIGHT-HO,” said Algy Crufts. “Then I shall go alone.”

“Right-ho,” said Ambrose Wiffin. “Go alone.”

“Right-ho,” said Algy Crufts. “I will.”

“Right-ho,” said Ambrose Wiffin. “Do.”

“Right-ho, then,” said Algy Crufts.

“Right-ho,” said Ambrose Wiffin.

“Right-ho,” said Algy Crufts.

Few things are more painful than an altercation between two boyhood friends. Nevertheless, when these occur, the conscientious historian must record them.

It is also, no doubt, the duty of the historian to be impartial. In the present instance, however, it would be impossible to avoid bias. To realize that Algy Crufts was perfectly justified in taking an even stronger tone, one has only to learn the facts. It was the season of the year when there comes upon all right-thinking young men the urge to buzz off to Monte Carlo; and the scheme had been that he and Ambrose should edge into the ten o’clock boat-train on the morning of the sixteenth of February. All the arrangements had been made—the tickets (billets) bought; the trunks packed; the “One Hundred Systems of Winning at Roulette” studied from end to end; and here was Ambrose, on the afternoon of February the fourteenth, oiling in and saying that he proposed to remain in London for another fortnight.

Algy Crufts eyed him narrowly. Ambrose Wiffin was always a nattily-dressed young man, but to-day there had crept into his outer crust a sort of sinister effulgence which could have but one meaning. It shouted from his white carnation; it shrieked from his lemon-coloured spats; and Algy read it in a flash.

“You’re messing about after some beastly female,” he said.

Ambrose Wiffin reddened and brushed his top-hat the wrong way.

“And I know who it is. It’s that Wickham girl.”

Ambrose reddened again, and brushed his top-hat once more—this time the right way, restoring the status quo.

“Well,” he said, “you introduced me to her.”

“I know I did. And, if you recollect, I drew you aside immediately afterwards and warned you to watch your step.”

“If you have anything to say against Miss Wickham——”

“I haven’t anything to say against her. She’s one of my best pals. I’ve known young Bobbie Wickham since she was a kid in arms, and I’m what you might call immune where she’s concerned. But you can take it from me that every other fellow who comes in contact with Bobbie finds himself sooner or later up to the Adam’s apple in some ghastly mess. She lets them down with a dull, sickening thud. Look at Roland Attwater. He went to stay at her place, and he had a snake with him——”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. He happened to have a snake with him, and Bobbie put it in a fellow’s bed and let everyone think it was Attwater who had done it. He had to leave by the milk-train at three in the morning.”

“Attwater had no business lugging snakes about with him to country houses,” said Ambrose, primly. “One can readily understand how a high-spirited girl would feel tempted——”

“And then there was Dudley Finch. She asked him down for the night and forgot to tell her mother he was coming, with the result that he was taken for a Society burglar and got shot in the leg by the butler as he was leaving to catch the milk-train.”

A look such as Sir Galahad might have worn on hearing gossip about Queen Guinevere lent a noble dignity to Ambrose Wiffin’s pink young face.

“I don’t care,” he said, stoutly. “She’s the sweetest girl on earth, and I’m taking her to the Dog Show on Saturday.”

“Eh? What about our Monte Carlo binge?”

“That’ll have to be postponed. Not for long. She’s up in London, staying with an aunt of sorts, for another couple of weeks. I could come after that.”

“Do you mean to say you have the immortal crust to expect me to hang about for two weeks, waiting for you?”

“I don’t see why not.”

“Oh, don’t you? Well, I’m jolly well not going to.”

“Right-ho. Just as you like.”

“Right-ho. Then I shall go alone.”

“Right-ho. Go alone.”

“Right-ho. I will.”

“Right-ho. Do.”

“Right-ho, then.”

“Right-ho,” said Ambrose Wiffin.

“Right-ho,” said Algy Crufts.

AT almost exactly the moment when this very distressing scene was taking place at the Drones Club in Dover Street, Roberta Wickham, in the drawing-room of her aunt Marcia’s house in Eaton Square, was endeavouring to reason with her mother and finding the going a bit sticky. Lady Wickham was notoriously a difficult person to reason with. She was a woman who knew her mind.

“But, mother!”

Lady Wickham advanced her forceful chin another inch. She had rather prominent features and, in addition, an eye like Mars to threaten and command.

“It’s no use arguing, Roberta——”

“But, mother! I keep telling you. Jane Falconer has just rung up and wants me to go round and help her choose the cushions for her new flat.”

“And I keep telling you that a promise is a promise. You voluntarily offered after breakfast this morning to take your cousin Wilfred and his little friend Esmond Bates to the moving-pictures to-day, and you cannot disappoint them now.”

“But if Jane’s left to herself she’ll choose the most awful things.”

“I cannot help that.”

“She’s relying on me. She said so. And I swore I’d go.”

“I cannot help that.”

“I’d forgotten all about Wilfred.”

“I cannot help that. You should not have forgotten. You must ring your friend up and tell her that you are unable to see her this afternoon. I think you ought to be glad of the chance of giving pleasure to these two boys. One ought not always to be thinking of oneself. One ought to try to bring a little sunshine into the lives of others. I will go and tell Wilfred you are waiting for him.”

Left alone, the girl wandered morosely to the window and stood looking down into the Square. The faint light of the February afternoon gleamed on her striking red hair, but there was no accompanying gleam in her hazel eyes. Her aspect was that of a girl who is fed to the teeth. From where she stood she was able to observe a small boy in an Eton suit sedulously hopping from the pavement to the bottom step of the house and back again. This was Esmond Bates, next-door’s son and heir, and the effect the sight of him had on Bobbie was to drive her from the window and send her slumping on to the sofa, where for a space she sat, gazing before her and disliking life. It may not seem to everybody the summit of human pleasure to go about London choosing cushions, but Bobbie had set her heart on it; and the iron was entering deeply into her soul when the door opened and the butler appeared.

“Mr. Wiffin,” announced the butler. And Ambrose walked in, glowing with that holy, reverential emotion which always surged over him at the sight of Bobbie.

Usually there was blended with this a certain diffidence, unavoidable in one visiting the shrine of a goddess; but to-day the girl seemed so unaffectedly glad to see him that diffidence vanished. He was amazed to note how glad she was to see him. She had bounded from the sofa on his entry, and now was looking at him with shining eyes like a shipwrecked mariner who sights a sail.

“Oh, Ambrose!” said Bobbie. “I’m so glad you came.”

Ambrose thrilled from his quiet but effective sock-clocks to his Stacombed hair. How wise, he felt, he had been to spend that long hour perfecting the minutest details of his toilet. As a glance in the mirror on the landing had just assured him, his hat was right, his coat was right, his trousers were right, his shoes were right, his buttonhole was right, and his tie was right. He was one hundred per cent., and girls appreciate such things.

“Just thought I’d look in,” he said, speaking in the guttural tones which agitated vocal cords always forced upon him when addressing the queen of her species, “and see if you were doing anything this afternoon. If,” he added, “you see what I mean.”

“I’m taking my cousin Wilfred and a little friend of his to the movies. Would you like to come?”

“I say! Thanks awfully! May I?”

“Yes, do.”

“I say! Thanks awfully!” He gazed at her with worshipping admiration. “But, I say, how frightfully kind of you to mess up an afternoon taking a couple of kids to the movies. Awfully kind. I mean kind. I mean I call it dashed kind of you.”

“Oh, well!” said Bobbie, modestly. “I think I ought to be glad of the chance of giving pleasure to these two boys. One ought not always to be thinking of oneself. One ought to try to bring a little sunshine into the lives of others.”

“You’re an angel!”

“No, no.”

“An absolute angel,” insisted Ambrose, quivering fervently. “Doing a thing like this is—well, absolutely angelic. If you follow me. I wish Algy Crufts had been here to see it.”

“Why Algy?”

“Because he was saying some very unpleasant things about you this afternoon. Most unpleasant things.”

“What did he say?”

“He said——” Ambrose winced. The vile words were choking him. “He said you let people down.”

“Did he? Did he, forsooth? I’ll have to have a word with young Algernon P. Crufts. He’s getting above himself. He seems to forget,” said Bobbie, a dreamy look coming into her beautiful eyes, “that we live next to each other in the country and that I know which his room is. What young Algy wants is a frog in his bed.”

“Two frogs,” amended Ambrose.

“Two frogs,” agreed Bobbie.

The door opened and there appeared on the mat a small boy. He wore an Eton suit, spectacles, and, low down over his prominent ears, a bowler hat; and Ambrose thought he had seldom seen anything fouler. He would have looked askance at Royalty itself, had Royalty interrupted a tête-à-tête with Miss Wickham.

“I’m ready,” said the boy.

“This is Aunt Marcia’s son Wilfred,” said Bobbie.

“Oh?” said Ambrose, coldly.

Like so many young men, Ambrose Wiffin was accustomed to regard small boys with a slightly jaundiced eye. It was his simple creed that they wanted their heads smacked. When not having their heads smacked, they should be out of the picture altogether. He stared disparagingly at this specimen. A half-formed resolve to love him for Bobbie’s sake perished at birth. Only the thought that Bobbie would be of the company enabled him to endure the prospect of being seen in public with this outstanding piece of cheese.

“Let’s go,” said the boy.

“All right,” said Bobbie. “I’m ready.”

“We’ll find Old Stinker on the steps,” the boy assured her, as one promising a deserving person some delightful treat.

OLD STINKER, discovered as predicted, seemed to Ambrose just the sort of boy who would be a friend of Bobbie’s cousin Wilfred. He was goggle-eyed and freckled, and also, as it was speedily to appear, an officious little devil who needed six of the best with a fives-bat.

“The cab’s waiting,” said Old Stinker.

“How clever of you to have found a cab, Esmond,” said Bobbie, indulgently.

“I didn’t find it. It’s his cab. I told it to wait.”

A stifled exclamation escaped Ambrose, and he shot a fevered glance at the taxi’s clock. The sight of the figures on it caused him a sharp pang. Not six with a fives-bat, he felt. Ten. And of the juiciest.

“Splendid,” said Bobbie. “Hop in. Tell him to drive to the Tivoli.”

Ambrose suppressed the words he had been about to utter, and, climbing into the cab, settled himself down and devoted his attention to trying to avoid the feet of Bobbie’s cousin Wilfred, who sat opposite him. The boy seemed as liberally equipped with these as a centipede, and there was scarcely a moment when his boots were not rubbing the polish off Ambrose’s glittering shoes. It was with something of the emotions of the Ten Thousand Greeks on beholding the sea that at long last he sighted the familiar architecture of the Strand. Soon he would be sitting next to Bobbie in a dimly-lighted auditorium, and a man with that in prospect could afford to rough it a bit on the journey. He alighted from the cab and plunged into the queue before the box-office.

Wedged in among the crowd of pleasure-seekers, Ambrose, though physically uncomfortable, felt somehow a sort of spiritual refreshment. There is nothing a young man in love finds more delightful than the doing of some knightly service for the loved one; and though to describe as a knightly service the act of standing in a queue and buying tickets for a motion-picture entertainment may seem to the more hard-boiled of the reading public straining the facts a little, to one in Ambrose’s condition a service is a service. He would have preferred to be called upon to save Bobbie’s life; but, this not being at the moment feasible, it was something to be jostling in a queue for her sake.

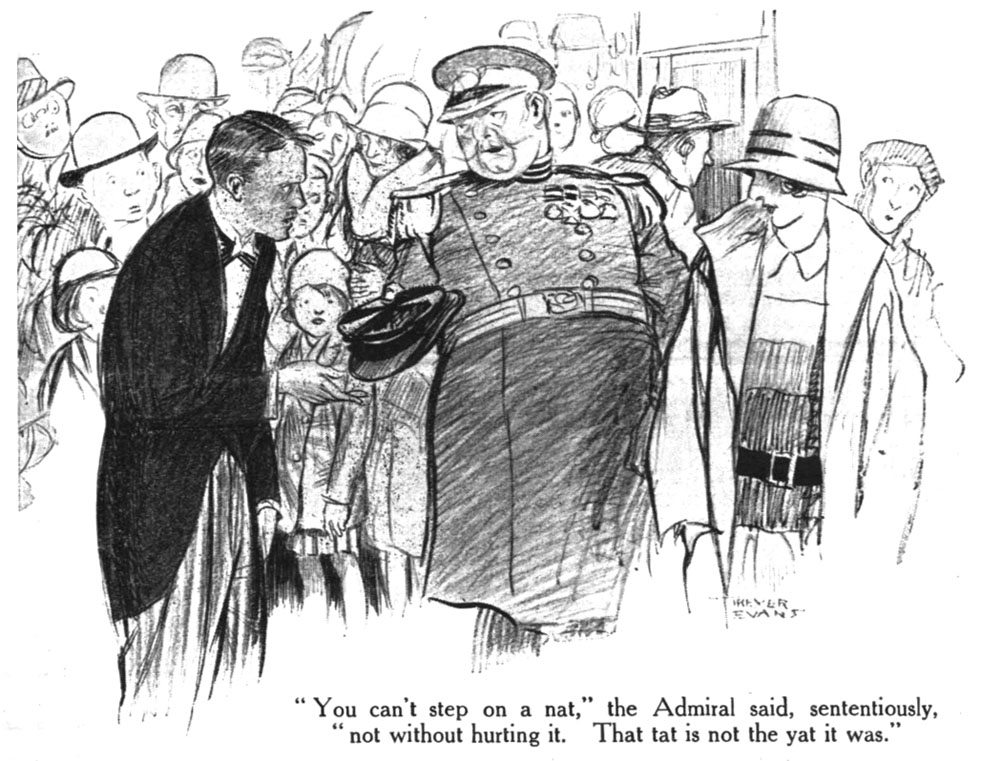

Nor was the action so free from peril as might appear at first sight. Sheer, black disaster was lying in wait for Ambrose Wiffin. He had just forced his way to the pay-box and was turning to leave after buying the tickets when the thing happened. From somewhere behind him an arm shot out, there was an instant’s sickening suspense, and then the top-hat which he loved nearly as much as life itself was rolling across the lobby with a stout man in the uniform of a Czecho-Slovakian Rear-Admiral in pursuit.

In the sharp agony of this happening, it had seemed to Ambrose that he had experienced the worst moment of his career. Then he discovered that it was in reality the worst but one. The sorrow’s crown of sorrow was achieved an instant later when the Admiral returned, bearing in his hand a battered something which for a space he was unable to recognize.

The Admiral was sympathetic. There was a bluff, sailorly sympathy in his voice as he spoke.

“Here you are, sir,” he said. “Here’s your rat. A little the worse for wear, this sat is, I’m afraid, sir. A gentleman happened to step on it. You can’t step on a nat,” he said, sententiously, “not without hurting it. That tat is not the yat it was.”

Although he spoke in the easy manner of one making genial conversation, his voice had in it a certain purposeful note. He seemed like a Rear-Admiral who was waiting for something; and Ambrose, as if urged by some hypnotic spell, produced half a crown and pressed it into his hand. Then, placing the remains on his head, he tottered across the lobby to join the girl he loved.

That she could ever, after seeing him in a hat like that, come to love him in return seemed to him at first unbelievable. Then Hope began to steal shyly back. After all, it was in her cause that he had suffered this great blow. She would take that into account. Furthermore, girls of Roberta Wickham’s fine fibre do not love a man entirely for his hat. The trousers count, so do the spats. It was in a spirit almost optimistic that he forced his way through the crowd to the spot where he had left the girl. And as he reached it the squeaky voice of Old Stinker smote his ear.

“Golly!” said Old Stinker. “What have you done to your hat?”

Another squeaky voice spoke. Aunt Marcia’s son Wilfred was regarding him with the offensive interest of a biologist examining some lower organism under the microscope.

“I say,” said Wilfred, “I don’t know if you know it, but somebody’s been sitting on your hat, or something. Did you ever see a hat like that, Stinker?”

“Never in my puff,” replied his friend.

Ambrose gritted his teeth.

“Never mind my hat! Where’s Miss Wickham?”

“Oh, she had to go,” said Old Stinker.

It was not for a moment that the hideous meaning of the words really penetrated Ambrose’s consciousness. Then his jaw fell and he stared aghast.

“Go? Go where?”

“I don’t know where. She went.”

“She said she had just remembered an appointment,” explained Wilfred. “She said——”

“——that you were to take us in and she would join us later if she could.”

“She rather thought she wouldn’t be able to, but she said leave her ticket at the box-office in case.”

“She said she knew we would be all right with you,” concluded Old Stinker. “Come on, let’s beef in or we’ll be missing the educational two-reel comic.”

Ambrose eyed them wanly. All his instincts urged him to smack these two heads as heads should be smacked, to curse a good deal, to wash his hands of the whole business and stride away. But Love conquers all. Reason told him that here were two small boys, a good deal ghastlier than any small boy he had yet encountered. In short, mere smack-fodder. But Love, stronger than Reason, whispered that they were a sacred trust. Roberta Wickham expected him to take them to the movies and he must do it.

And such was his great love that not yet had he begun to feel any resentment at this desertion of hers. No doubt, he told himself, she had had some good reason. In anyone a shade less divine, the act of sneaking off and landing him with these two disease-germs might have seemed culpable; but what he felt at the moment was that the Queen could do no wrong.

“Oh, all right,” he said, dully. “Push in.”

Old Stinker had not yet exhausted the theme of the hat.

“I say,” he observed, “that hat looks pretty rummy, you know.”

“Absolutely weird,” assented Wilfred.

Ambrose regarded them intently for a moment, and his gloved hand twitched a little. But the iron self-control of the Wiffins stood him in good stead.

“Push in,” he said in a strained voice. “Push in.”

IN the last analysis, however many highly-salaried stars its cast may contain, and however superb and luxurious the settings of its orgy-scenes, the success of a super-film’s appeal to an audience must always depend on what company each unit of that audience is in when he sees it. Start wrong in the vestibule, and entertainment in the true sense is out of the question.

For the picture which the management of the Tivoli was now presenting to its patrons Hollywood had done all that Art and Money could effect. Based on Wordsworth’s well-known poem, “We are Seven,” it was entitled “Where Passion Lurks,” and offered such notable favourites of the silver screen as Laurette Byng, G. Cecil Terwilliger, Baby Bella, Oscar the Wonder-Poodle, and Professor Pond’s Educated Sea-Lions. And yet it left Ambrose cold.

If only Bobbie had been at his side, how different it all would have been. As it was, the beauty of the story had no power to soothe him, nor could he get the slightest thrill out of the Babylonian Banquet scene, which had cost five hundred thousand dollars. From start to finish he sat in a dull apathy; then, at last, the ordeal over, he stumbled out into daylight and the open air. Like G. Cecil Terwilliger at a poignant crisis in the fourth reel, he was as one on whom Life has forced its bitter cup and who has drained it to the lees.

And it was this moment, when a strong man stood face to face with his soul, that Old Stinker with the rashness of Youth selected for beginning again about the hat.

“I say,” said Old Stinker, as they came out into the bustling Strand, “you’ve no idea what an ass you look in that napper.”

“Priceless,” agreed Wilfred, cordially. “A perfect mess.”

“All you want is a banjo and you could make a fortune singing comic songs outside the pubs.”

On his first introduction to these little fellows it had seemed to Ambrose that they had touched the lowest possible level to which humanity can descend. It now became apparent that there were hitherto unimagined depths which it was in their power to plumb. There is a point beyond which even a Wiffin’s self-control fails to function. The next moment, above the roar of London’s traffic there sounded the crisp note of a well-smacked head.

It was Wilfred who, being nearest, had received the treatment; and it was at Wilfred that an elderly lady, pausing, pointed with indignant horror in every waggle of her finger-tip.

“Why did you strike that little boy?” demanded the elderly lady.

Ambrose made no answer. He was in no mood for riddles. Besides, to reply fully to the question he would have been obliged to trace the whole history of his love, to dilate on the agony it had caused him to discover that his goddess had feet of clay, to explain how little by little through the recent entertainment there had grown a fever in his blood, caused by this boy sucking peppermints, shuffling his feet, giggling, and reading out the sub-titles. Lastly, he would have had to discuss at length the matter of the hat.

Unequal to these things, he merely glowered; and such was the calibre of his scowl that the other supposed that here was the authentic Abysmal Brute.

“I’ve a good mind to call a policeman,” she said.

It is a peculiar phenomenon of life in London that the magic word “policeman” has only to be whispered in any of its thoroughfares to attract a crowd of substantial dimensions; and Ambrose, gazing about him, now discovered that their little group had been augmented by some thirty citizens, each of whom was regarding him in much the same way that he would have regarded the accused in a big murder-trial at the Old Bailey.

A passionate desire to be elsewhere came upon the young man. Of all things in this life he disliked most a scene; and this was plainly working up into a scene of the worst kind. Seizing his sacred trusts by the elbow, he ran them across the street. The crowd continued to stand and stare at the spot where the incident had occurred.

FOR some little time, safe on the opposite pavement, Ambrose was too busily occupied in reassembling his disintegrated nervous system to give any attention to the world about him. He was recalled to mundane matters by a piercing squeal of ecstasy from his young companions.

“Oo! Oysters!”

“Golly! Oysters!”

And he became aware that they were standing outside a restaurant whose window was deeply paved with these shellfish. On these the two lads were gloating with bulging eyes.

“I could do with an oyster!” said Old Stinker.

“So could I jolly well do with an oyster,” said Wilfred.

“I bet I could eat more oysters than you.”

“I bet you couldn’t.”

“I bet I could.”

“I bet you couldn’t.”

“I bet you a million pounds I could.”

“I bet you a million trillion pounds you couldn’t.”

Ambrose had had no intention of presiding over the hideous sporting contest which they appeared to be planning. Apart from the nauseous idea of devouring oysters at half-past four in the afternoon, he resented the notion of spending any more of his money on these gargoyles. But at this juncture he observed, threading her way nimbly through the traffic, the elderly lady who had made the scene. A Number 33 omnibus could quite easily have got her, but by sheer carelessness failed to do so; and now she was on the pavement and heading in their direction. There was not an instant to be lost.

“Push in,” he said, hoarsely. “Push in.”

A moment later they were seated at a table and a waiter who looked like one of the executive staff of the Black Hand was hovering beside them with pencil and pad.

Ambrose made one last appeal to his guests’ better feelings.

“You can’t really want oysters at this time of day,” he said, almost pleadingly.

“I bet you we can,” said Old Stinker.

“I bet you a billion pounds we can,” said Wilfred.

“Oh, all right,” said Ambrose. “Oysters.”

He sank back in his chair and endeavoured to avert his eyes from the grim proceedings. Æons passed, and he was aware that the golluping noises at his side had ceased. All things end in time. Even the weariest river winds somewhere to the sea. Wilfred and Old Stinker had stopped eating oysters.

“Finished?” he asked in a cold voice.

There was a moment’s pause. The boys seemed hesitant.

“Yes, if there aren’t any more.”

“There aren’t,” said Ambrose. He beckoned to the waiter, who was leaning against the wall dreaming of old, happy murders of his distant youth. “L’addition,” he said, curtly.

“Sare?”

“The bill.”

“The pill? Oh, yes, sare.”

Shrill and jovial laughter greeted the word.

“He said ‘pill’!” gurgled Old Stinker.

“ ‘Pill’!” echoed Wilfred.

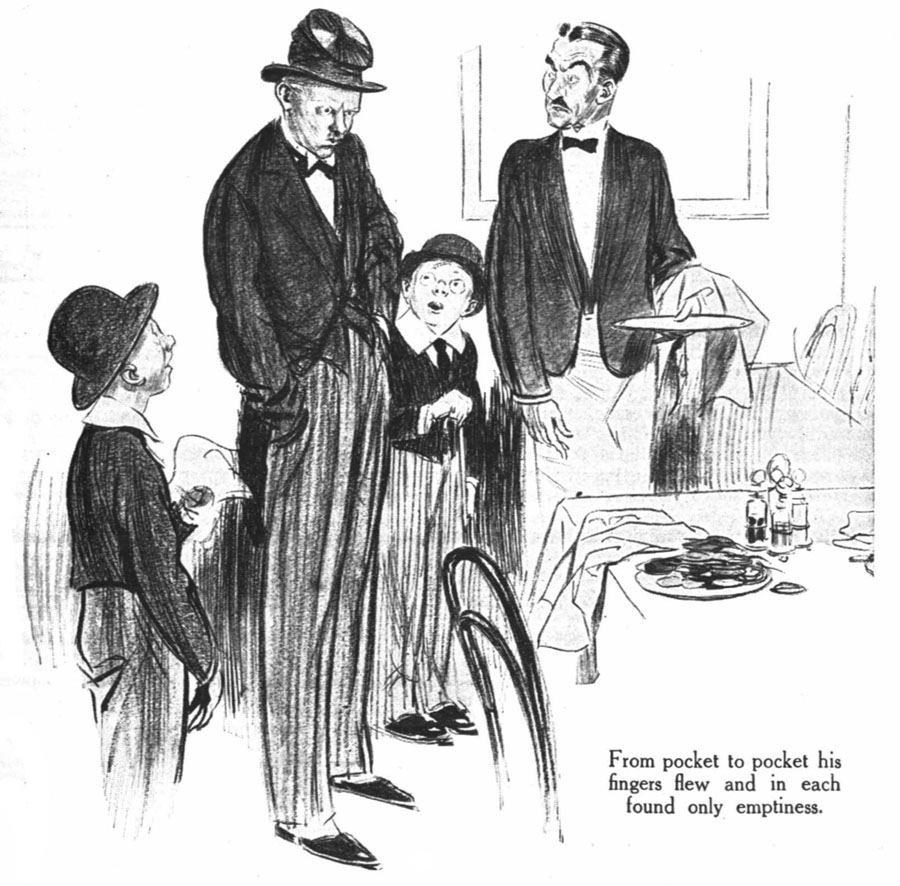

They punched each other distractedly to signify their appreciation of this excellent comedy. The waiter, flushing darkly, muttered something in his native tongue and seemed about to reach for his stiletto. Ambrose reddened to the eyebrows. Laughing at waiters was simply one of the things that aren’t done, and he felt his position acutely. It was a relief when the Black Hander returned with his change.

There was only a solitary sixpence on the plate, and Ambrose hastened to dip in his pocket for further coins to supplement this. A handsome tip would, he reasoned, show the waiter that, though circumstances had forced these two giggling outcasts upon him, spiritually he had no affiliation with them. It would be a gesture which would put him at once on an altogether different plane. The man would understand that, dubious though the company might be in which he had met him, Ambrose Wiffin himself was all right and had a heart of gold. “Simpatico,” he believed these Italians called it.

And then he jumped up, tingling as from an electric shock. From pocket to pocket his fingers flew and in each found only emptiness. The awful truth was clear. An afternoon spent in paying huge taxi-fares, buying seats for motion-picture performances, pressing half-crowns into the palms of Czecho-Slovakian Rear-Admirals, and filling small boys with oysters had left him a financial ruin. That sixpence was all he had to get these two blighted boys back to Eaton Square.

AMBROSE WIFFIN paused at the cross-roads. In all his life he had never left a waiter untipped. He had not supposed it could be done. He had looked upon the tipping of waiters as a natural process, impossible to evade, like breathing or leaving the bottom button of your waistcoat unfastened. Ghosts of bygone Wiffins—Wiffins who had scattered largess to the multitude in the Middle Ages, Wiffins who in Regency days had flung landlords purses of gold—seemed to crowd at his elbow, imploring the last of their line not to disgrace the family name. On the other hand, sixpence would just pay for bus-fares and remove from him the necessity of walking two miles through the streets of London in a squashed top-hat and in the society of Wilfred and Old Stinker.

If it had been Wilfred alone—or even Old Stinker alone—or if that hat did not look so extraordinarily like something off the stage of a low-class music-hall——

Ambrose Wiffin made the great decision. Pocketing the sixpence with one swift motion of the hand and breathing heavily through his nose, he made for the door.

“Come on!” he growled.

He could have betted on his little friends. They acted just as he had expected they would. No tact. No reticence. Not an effort towards handling the situation. Just two bright young children of Nature who said the first thing that came into their heads and who, he hoped, would wake up to-morrow morning with ptomaine-poisoning.

“I say!” It was Wilfred who gave tongue first of the pair, and his clear voice rang through the restaurant like a bugle. “You haven’t tipped him!”

“I say!” Old Stinker chimed in, extraordinarily bell-like. “Dash it all, aren’t you going to tip him?”

“You haven’t tipped the waiter,” said Wilfred, making his meaning clearer.

“The waiter,” explained Old Stinker, clarifying the situation of its last trace of ambiguity. “You haven’t tipped him!”

“Come on!” said Ambrose. “Push out! Push out!”

A hundred dead Wiffins shrieked a ghostly shriek and covered their faces with their winding-sheets. A stunned waiter clutched his napkin to his breast. And Ambrose, with bowed head, shot out of the door like a conscience-stricken rabbit. In that supreme moment he even forgot that he was wearing a top-hat like a concertina. So true is it that the greater emotion swallows up the less.

A heaven-sent omnibus stopped before him in a traffic-block. He pushed his little charges in, and, as they charged in their gay, boyish way to the farther end of the vehicle, seated himself next to the door, as far away from them as possible. Then, removing the hat, he sat back and closed his eyes.

Hitherto, when sitting back with closed eyes, it had always been the custom of Ambrose Wiffin to give himself up to holy thoughts about Bobbie. But now they refused to come. Plenty of thoughts, but not holy ones. It was as though the supply had petered out.

Too dashed bad of the girl, he meant, letting him in for a thing like this. Absolutely too dashed bad of her. And, mark you, she had intended from the very beginning, mind you, to let him in for it. Oh, yes, she had. All that about suddenly remembering an appointment, he meant to say. Perfect rot. Wouldn’t hold water for a second. She had never had the least intention of coming into that bally moving-picture place. Right from the start she had planned to lure him into the thing and then ooze off and land him with these septic kids, and what he meant was that it was too dashed bad of her.

Yes, the verdict might be severe, but he declined to mince his words. Too dashed bad. Not playing the game. A bit thick. In short—well, to put it in a nutshell, too dashed bad.

The omnibus rolled on. Ambrose opened his eyes in order to note progress. He was delighted to observe that they were already nearing Hyde Park Corner. At last he permitted himself to breathe freely. His martyrdom was practically over. Only a little longer now, only a few short minutes, and he would be able to deliver the two pestilences f.o.b. at their dens in Eaton Square, wash them out of his life for ever, return to the comfort and safety of his cosy rooms in the Albany, and there begin life anew.

The thought was heartening; and Ambrose, greatly restored, turned to sketching out in his mind the details of the drink which his man, under his own personal supervision, should mix for him immediately upon his return. As to this he was quite clear. Many men in his position—practically, you might say, saved at last from worse than death—would make it a stiff whisky-and-soda. But Ambrose, though he had no prejudice against whisky-and-soda, felt otherwise. It must be a cocktail. The cocktail of a lifetime. A cocktail that would ring down the ages, in which gin blended smoothly with Italian vermouth and the spot of old brandy nestled like a trusting child against the dash of absinthe. . . .

He sat up sharply. He stared. No, his eyes had not deceived him. At the far end of the omnibus Trouble was rearing its ugly head.

ON occasions of great disaster it is seldom that the spectator perceives instantly every detail of what is toward. The thing creeps upon him gradually, impinging itself upon his consciousness in progressive stages. All that the inhabitants of Pompeii, for example, observed in the early stages of that city’s doom was probably a mere puff of smoke. “Ah!” they said, “a puff of smoke!” and let it go at that. So with Ambrose Wiffin in the case of which we are treating.

The first thing that attracted Ambrose’s attention was the face of a man who had come in at the last stop and seated himself immediately opposite Old Stinker. It was an extraordinarily solemn face, spotty in parts and bathed in a rather remarkable crimson flush. The eyes, which were prominent, wore a fixed, far-away look. Ambrose had noted them as they passed him. They were round, glassy eyes. They were, briefly, the eyes of a man who has lunched.

In the casual way in which one examines one’s fellow-passengers on an omnibus, Ambrose had allowed his gaze to flit from time to time to this person’s face. For some minutes its expression had remained unaltered. The man might have been sitting for his photograph. But now into the eyes there was creeping a look almost of animation. The flush had begun to deepen. For some reason or other, it was plain, the machinery of the brain was starting to move once more.

Ambrose watched him idly. No premonition of doom came to him. He was simply mildly interested. And then, little by little, there crept upon him a faint sensation of discomfort.

The man’s behaviour had now begun to be definitely peculiar. There was only one adjective to describe his manner, and that was the adjective odd. Slowly he had heaved himself up into a more rigid posture, and with his hands on his knees was bending slightly forward. His eyes had taken on a still glassier expression, and now with the glassiness was blended horror. Unmistakable horror. He was staring fixedly at some object directly in front of him.

It was a white mouse. Or, rather, at present merely the head of a white mouse. This head, protruding from the breast-pocket of Old Stinker’s jacket, was moving slowly from side to side. Then, tiring of confinement, the entire mouse left the pocket, climbed down its proprietor’s person until it reached his knee, and, having done a little washing and brushing-up, twitched its whiskers and looked across with benevolent pink eyes at the man opposite. The latter drew a sharp breath, swallowed, and moved his lips for a moment. It seemed to Ambrose that he was praying.

The glassy-eyed passenger was a man of resource. Possibly this sort of thing had happened to him before and he knew the procedure. He now closed his eyes, kept them closed for perhaps half a minute, then opened them again.

The mouse was still there.

It is at moments such as this that the best comes out in a man. You may impair it with a series of injudicious lunches, but you can never wholly destroy the spirit that has made Englishmen what they are. When the hour strikes, the old bulldog strain will show itself. Shakespeare noticed the same thing. His back against the wall, an Englishman, no matter how well he has lunched, will always sell his life dearly.

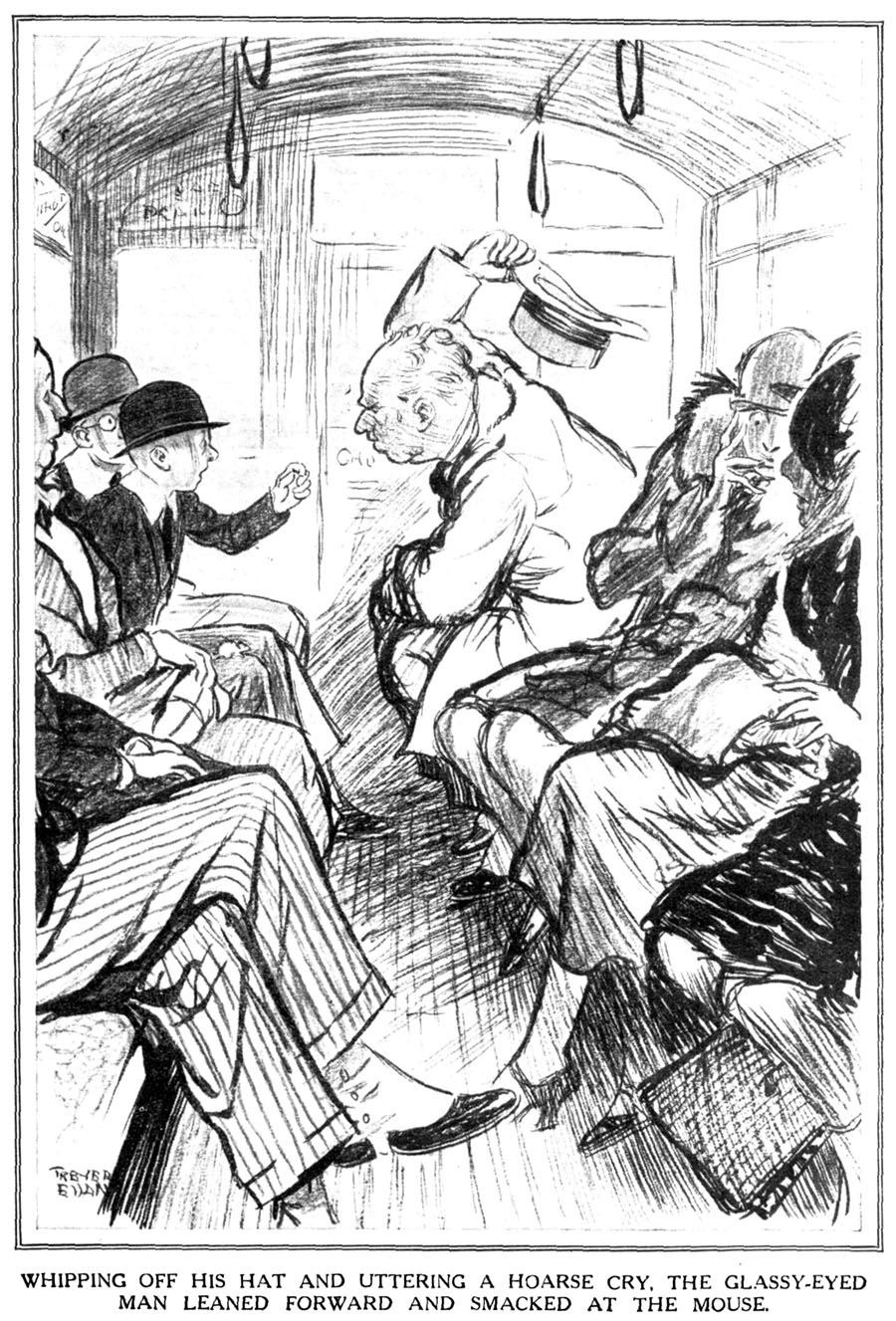

The glassy-eyed man, as he would have been the first to admit, had had just that couple over the eight which make all the difference, but he was a Briton. Whipping off his hat and uttering a hoarse cry—possibly, though the words could not be distinguished, that old, heart-stirring appeal to St. George which rang out over the fields of Agincourt and Crécy—he leaned forward and smacked at the mouse.

The mouse had seen it coming. It did the only possible thing. It side-stepped and, slipping to the floor, went into retreat there. And then from every side there arose the stricken cries of women in peril.

History, dealing with the affair, will raise its eyebrows at the conductor of the omnibus. He was patently inadequate. He pulled a cord, stopped the vehicle, and, advancing into the interior, said “ ’Ere!” Napoleon might just as well have said “ ’Ere!” at the Battle of Waterloo. Forces far beyond the control of mere words had been unchained. Old Stinker was kicking the glassy-eyed passenger’s shin. The glassy-eyed man was protesting that he was a gentleman. Three women were endeavouring simultaneously to get through an exit planned by the omnibus’s architect to accommodate but one traveller alone.

And then a massive, uniformed figure was in their midst.

“Wot’s this?”

Ambrose waited no longer. He had had sufficient. Edging round the new-comer, he dropped from the omnibus and with swift strides vanished into the darkness.

THE morning of February the fifteenth came murkily to London in a mantle of fog. It found Ambrose Wiffin breakfasting in bed. On the tray before him was a letter. Twenty-four hours ago the sight of that handwriting would have set his heart a-flutter beneath his orange pyjamas, but now he regarded it coldly. Physically he was in the pink, but he no longer loved. His heart was dead, he regarded the opposite sex as a wash-out, and letters from Bobbie Wickham could stir no chord.

He had already perused this letter, but now he took it up once more and, his lips curved in a bitter smile, ran his eyes over it again, noting some of its high spots.

“ . . . very disappointed in you . . . cannot understand how you could have behaved in such an extraordinary way . . .”

Ha!

“ . . . did think I could have trusted you to look after . . . And then you go and leave the poor little fellows alone in the middle of London . . .”

Oh, ha, ha!

“ . . . Wilfred arrived home in charge of a policeman, and mother is furious. I don’t think I have ever seen her so pre-War . . .”

Ambrose Wiffin threw the letter down and picked up the telephone.

“Hullo!”

“Hullo!”

“Algy?”

“Yes. Who’s that?”

“Ambrose Wiffin.”

“Oh? What-ho!”

“What-ho!”

“I say,” said Algy Crufts, “what became of you yesterday afternoon? I kept trying to get you on the ’phone and you were out.”

“Sorry,” said Ambrose Wiffin. “I was taking a couple of kids to the movies.”

“What on earth for?”

“Oh, well, one likes to get the chance of giving a little pleasure to people, don’t you know. One ought not always to be thinking of oneself. One ought to try to bring a little sunshine into the lives of others.”

“I suppose,” said Algy, sceptically, “that, as a matter of fact, young Bobbie Wickham was with you, too, and you held her bally hand all the time.”

“Nothing of the kind,” replied Ambrose Wiffin with dignity. “Miss Wickham was not among those present. What were you trying to get me on the ’phone about yesterday?”

“To ask you not to be a chump and stay hanging about London in this beastly weather. Ambrose, old bird, you simply must come to-morrow.”

“Algy, old cork, I was just going to ring you up to say I would.”

“You were?”

“Absolutely.”

“Great work! Sound egg! Right-ho, then, I’ll meet you under the clock at Victoria at half-past nine.”

“Right-ho. I’ll be there.”

“Right-ho. Under the clock.”

“Right-ho. The good old clock.”

“Right-ho,” said Algy Crufts.

“Right-ho,” said Ambrose Wiffin.

Annotations to this story as it appeared in book form are in the notes to Mr. Mulliner Speaking on this site.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums