The Strand Magazine, February 1912

CHAPTER I.

the telegram from mervo.

ETTY SILVER came out of the house

and began to walk slowly across the terrace to where Elsa Keith sat with Martin

Rossiter in the shade of the big sycamore. Elsa and Martin had become engaged

some few days before.

ETTY SILVER came out of the house

and began to walk slowly across the terrace to where Elsa Keith sat with Martin

Rossiter in the shade of the big sycamore. Elsa and Martin had become engaged

some few days before.

“What’s troubling Betty, I wonder?” said Elsa. “She looks worried.”

Martin turned his head.

“Is that your friend, Miss Silver? When did she arrive?”

“Last night. She’s here for a month. What’s the matter, Betty? This is Martin. What were you scowling at so ferociously, Betty?”

“Oh, Elsa, I’m miserable! I shall have to leave this heavenly place. See what has come!”

She held out some flimsy sheets of paper.

“A telegram!” said Elsa. “That’s not all one telegram, surely?”

“It’s from my stepfather. Read it out, Elsa. I want Mr. Rossiter to hear it. He may be able to tell me where Mervo is.”

Elsa, who had been skimming the document with raised eyebrows, now read it out in its spacious entirety:—

On receipt of this come instantly Mervo without moment delay. Vital importance. Presence urgently required. Come wherever you are. Cancel engagements. Urgent necessity. Have advised bank allow you draw any money you need expenses. Don’t fail catch first train London if you’re in the country. I don’t know where you are, but wherever you are you can catch boat-train to Dover to-morrow night. No taking root in London and spending a week shopping. Night boat Dover - Calais. Arrive Paris Wednesday morning. Dine Paris. Catch train-de-luxe nine-fifteen Wednesday night for Marseilles. Have engaged sleeping coupé. Now, mind—Wednesday night. No hanging round Paris shops—you can do all that later on. Just now I want you to get here quick. Arrive Marseilles Thursday morning. Boat Mervo Thursday night. Will meet you Mervo. Now, do you follow all that? Because, if not, wire at once and say which part of journey you don’t understand. Now mind special points to be remembered—Firstly, come instantly; secondly, no hanging round London-Paris shops. See?—Scobell.

“Well!” said Elsa, breathless.

Martin was re-reading the message.

“This isn’t a mere invitation,” he said. “There’s no come-along-you’ll-like-this-place-it’s-fine about it. He seems to look on your company more as a necessity than a luxury.”

“That’s what makes it so strange. We have hardly met for years. And I don’t know where he is!”

“Well,” said Martin, “if you get to the place by taking a boat from Marseilles, it can’t be far from the French coast. I should say that Mervo was an island in the Mediterranean. Isn’t there an Encyclopædia in the library, Elsa? I’ll go and fetch it.”

As he crossed the terrace, Elsa turned quickly to Betty.

“Well?” she said.

Betty smiled at her.

“He’s a dear. Are you very happy, Elsa?”

Elsa closed her eyes.

“It’s like eating strawberries and cream in a new dress by moonlight on a summer night, while somebody plays the violin far away in the distance, so that you can just hear it,” she said.

Betty was clenching her hands and breathing quickly.

“And it’s like——”

“Elsa, don’t! I can’t bear it!”

“Betty! What’s the matter?”

Betty smiled again, but painfully.

“It’s stupid of me. I’m just jealous, that’s all. I haven’t got a Martin, you see. You have.”

“Well, there are plenty who would like to be your Martin.”

Betty’s face grew cold.

“There are plenty who would like to be Benjamin Scobell’s son-in-law,” she said.

“Betty!” Elsa’s voice was serious. “Betty! Who are they?”

“The only one you know is Lord Arthur Hayling. You remember him? He was the last. There were four others before him. And not one of them cared the slightest bit about me.”

“But, Betty, dear, that’s just what I mean. Why should you say that? How can you know?”

“How do I know? Well, I do know. Instinct, I suppose. I can’t think of a single man in the world—except your Martin, of course—who wouldn’t do anything for money.” She stopped. “Well, yes, one.”

Elsa leaned forward eagerly.

“Who, Betty? What’s his name?”

Betty hesitated.

“Well, if I am in the witness-box—Maude, John Maude. I only met him two or three times, and I haven’t seen him for years, and I don’t suppose I shall ever see him again.”

“But how do you know, then? What makes you think that he——?”

“Instinct, again, I suppose. I do know.”

“And you’ve never met him since?”

Betty shook her head.

At the farther end of the terrace Martin Rossiter appeared, carrying a large volume.

He sat down and opened the book.

“Well, it’s an island in the Mediterranean, as I said. It’s the smallest independent State in the world; smaller than Monaco, even. Here are some facts. Its population when this Encyclopædia was printed—there may be more now—was eleven thousand and sixteen. It was ruled over up to 1886 by a Prince. But in that year the populace appear to have sacked their Prince, and the place is now a Republic.”

“But what can my stepfather be doing there? I last heard of him in America. Well, I suppose I shall have to go.”

“I suppose you will,” said Elsa, mournfully. “But, oh, Betty, what a shame!”

CHAPTER II.

mervo and its owner.

“By George!” cried Mr. Benjamin Scobell. “Hi, Marion!”

He wheeled round from the window and transferred his gaze from the view to his sister Marion.

Mervo was looking its best under the hot morning sun. Mr. Scobell’s villa stood near the summit of the only hill the island possessed, and from the window of the morning-room, where he had just finished breakfast, he had an uninterrupted view, of valley, town, and harbour—a two-mile riot of green, gold, and white, and beyond the white the blue satin of the Mediterranean.

Benjamin Scobell was not a nice man to hold despotic sway over such a Paradise. Somewhat below the middle height, he was lean of body and vulturine of face. He had a greedy mouth, a hooked nose, liquid green eyes, and a sallow complexion. He was rarely seen without a half-smoked cigar between his lips. This at intervals he would relight, only to allow it to go out again.

How he had discovered the existence of Mervo is not known. It lay well outside the sphere of the ordinary financier. But Mr. Scobell took a pride in the versatility of his finance. It distinguished him from the uninspired, who were content to concentrate themselves on steel, wheat, and such-like things. Ever since, as a young man in Manchester, he had founded his fortunes with a patent powder for the suppression of cockroaches, it had been his way to consider nothing as lying outside his sphere.

This man of many projects had descended upon Mervo like a stone on the surface of some quiet pool. Before his arrival Mervo had been an island of dreams and slow movement and putting things off till to-morrow. The only really energetic thing it had ever done in its whole history had been to expel his late Highness, Prince Charles, and change itself into a Republic. The Royalist party, headed by General Poineau, had been distracted but impotent. The army, one hundred and fifteen strong, had gone solid for the new régime. Mervo had then gone to sleep again. It was asleep when Mr. Scobell found it.

The financier’s scheme was first revealed to M. d’Orby, the President of the Republic. He was asleep in a chair on the porch of his villa when Mr. Scobell paid his call, and it was not until the financier’s secretary, Mr. Crump, who attended the séance in the capacity of interpreter, had rocked him vigorously from side to side for quite a minute that he displayed any signs of animation. When at length he opened his eyes, Mr. Scobell said, “I’ve a proposal to make to you, sir, and I’d like you to give your complete attention. I suppose you’ve heard of Moosieer Blonk—the feller who started the gaming-tables at Monte Carlo?”

Filtered through Mr. Crump, the question became intelligible to the President. He said he had heard of M. Blanc.

Mr. Scobell lit a cigar.

“Well, I’m in that line. I’m going to make this island hum just like old Blonk made Monte Carlo. I’ve been reading up all about Blonk, and I know just what he did and how he did it. Monte Carlo was just such another dead-and-alive little place as this is before he came. The Government was down to its last threepenny-bit and wondering where the dickens its next Sunday dinner was coming from, when along comes Blonk, tucks up his shirt-sleeves, and starts the tables. And after that the place never looked back. You and your fellows have got to call a meeting and pass a vote to give me a gambling concession here, like what they gave him. Scobell’s my name. Tell him, Crump.”

Mr. Crump obliged once more. A gleam of intelligence came into the President’s dull eye.

“The idea seems to strike him, sir,” said Mr. Crump.

“It ought to, if he’s got the imagination of a limpet,” replied Mr. Scobell. “Look here,” he said; “I’ve thought this thing out. There’s lots of room for another Monte Carlo. Monte’s a good little place, but it’s not perfect by a long way. Blonk’s offer to the Prince of Monaco was five hundred thousand francs a year—that’s about twenty thousand pounds in real money—and half the profits made by the Casino. That’s my offer, too. See how he likes that, Crump.”

Mr. Crump investigated.

“He says he accepts gladly, on behalf of the Republic, sir,” he announced.

M. d’Orby confirmed the statement by rising, dodging the cigar, and kissing Mr. Scobell on both cheeks.

“Stop it!” said the financier, austerely, breaking out of the clinch. “We’ll take the Apache dance as read. Good-bye, o’ man. Glad it’s settled. Now I can get to work.”

He did. Workmen poured into Mervo, and in a very short time, dominating the town and reducing to insignificance the palace of the late Prince, once a passably imposing mansion, there rose beside the harbour a mammoth Casino of shining stone.

It was a colossal venture, but it suffered from the defect from which most big things suffer: it moved slowly. At present it was being conducted at a loss. Ideas for promoting the prosperity of his nurseling came to Mr. Scobell at all hours—at meals, in the night watches, when he was shaving, walking, washing, reading, brushing his hair.

And now one had come to him as he stood looking at the view from the window of his morning-room.

“By George!” he said. “Marion, I’ve got an idea!”

Miss Scobell, deep in her paper, paid no attention. She had a detached mind.

“Marion!” cried Mr. Scobell. “I’ve got it. I’ve found out what’s the matter with this place. I see why the Casino hasn’t got moving properly. It’s this Republic. What’s the use of a Republic in a place like this? Who ever heard of this Republic doing anything except eat and sleep? They used to have a Prince here in ’eighty-something. Well, I’m going to have him back again.”

Miss Scobell looked up from her paper, which she had been reading with absorbed interest throughout this harangue.

“You can’t, dear. He’s dead,” said she.

“I know he’s dead. You can’t stump me on the history of this place. I’ve been reading it up. He died in ’91. But before he died he married an English girl, named Westley, and there’s a son, who’s in England now, living with his uncle. It’s the son I’m going to send for. I got it all from General Poineau.”

Miss Scobell turned to her paper again.

“Very well, dear,” she said. “Just as you please. I’m sure you know best.”

“I’ll go and find old Poineau at once,” said the financier. “He knows just where his nibs is.”

CHAPTER III.

john.

About the time of Mr. Scobell’s visit to General Poineau, John, Prince of Mervo, ignorant of the greatness so soon to be thrust upon him, was strolling thoughtfully along Bishopsgate Street.

He was a big young man, tall and large of limb. His face wore an expression of invincible good-humour.

As he passed along the street he looked a little anxious.

At the entrance to a large office-building he paused, and seemed to hesitate. Then, mounting to the second floor, he went down the passage, and pushed open a door on which was inscribed the legend, “Westley, Martin, and Co.”

A girl, walking across the office with her hands full of papers, stopped in astonishment.

“Why, John Maude!” she cried.

“Halloa, Della!” he said.

Della Morrison was an American girl, from New York. She was Mr. Westley’s secretary, and she and John had always been good friends. John, indeed, was generally popular with his fellow-employés.

“Say, where have you been?” said Della. “The old man’s been as mad as a hornet since he found you’d quit without leave.”

“Della,” said John, “owing to your unfortunate upbringing you aren’t a cricket enthusiast; but suppose you were, and suppose you got up one day and found it was a perfectly ripping morning, and remembered that it was the first day of a Test Match, and looked at your letters, and saw that someone had offered you a seat in the pavilion, what would you have done? I could no more have refused—oh, well, I suppose I’d better tackle my uncle now. It’s got to be done.”

John’s relations with his uncle were not cordial.

On Mr. Westley’s side there was something to be said in extenuation of his attitude. John reminded him of his father, and he had hated the late Prince of Mervo with a cold hatred that had for a time been the ruling passion of his life. He had loved his sister, and her married life had been one long torture to him, a torture rendered keener by the fact that he was powerless to protect either her happiness or her money. At last an automobile accident put an end to his Highness’s hectic career, and the Princess had returned to her brother’s home, where, a year later, she died, leaving him in charge of her infant son.

Mr. Westley’s desire from the first had been to eliminate, as far as possible, all memory of the late Prince. He gave John his sister’s name, Maude, and brought him up as an Englishman, in total ignorance of his father’s identity.

He disliked John intensely. He fed him, clothed him, sent him to Cambridge, and gave him a home and a place in his office; but he never for a moment relaxed his bleakness of front towards him.

As John approached the inner office the door flew open, disclosing Mr. Westley himself, a tall, thin man.

“Ah,” said Mr. Westley, “come in here. I want to speak to you.”

When the door closed Mr. Westley leaned back in his chair. “You were at the Test Match yesterday?” he said.

The unexpectedness of the question startled John into a sharp laugh.

“Yes,” he said, recovering himself.

“Without leave.”

“It didn’t seem worth while asking for leave.”

“You mean that you relied so implicitly on our relationship to save you from the consequences?”

“No; I meant——”

“Well, we need not try to discover what you may have meant. What claim do you put forward for special consideration? Why should I treat you differently from any other member of the staff?”

John had a feeling that the interview was being taken at too rapid a pace. He felt confused.

“I don’t want you to treat me differently,” he said.

“I think we understand each other,” said Mr. Westley. “I need not detain you. You may return to the Test Match without further delay. As you go out, ask the cashier to give you your salary to the end of the month. Good-bye.”

It was characteristic of John—a trait inherited from a long line of ancestors whose views on finance had always been delightfully airy and casual—that it was only at very occasional intervals that the thought would come to him that one cannot spend one’s days at the Oval and one’s nights in an expensive hotel indefinitely on a capital of forty pounds. But he was not a Prince of Mervo for nothing; and he shirked the unpleasant problem of how he was to go on living after his money was gone as thoroughly and effectively as even his father, the amiable Prince Charles, could have done. Life was too pleasant for such morbid meditations.

A certain tendency to loneliness was the only real drawback to his holiday. It was not until the fifth day that he met a friend, his old acquaintance, Della Morrison.

They met in the Savoy Hotel. She was so changed outwardly that, when he first caught sight of her, he did not recognize her.

She caught his eye, stared, then smiled a huge smile of delighted surprise.

“This is splendid,” said John. “I was just wondering if I should ever meet anybody I knew again. What are you doing here, Della? You look as if you had come into a fortune.”

“I have come into a fortune. At least, pa did. My head’s still buzzing. Pa and ma arrived from New York in the Lusitania the day after you were fired. They never cabled or anything. The first I knew of it was when they walked into the office and told me to get ready to quit, because I was an heiress. You never met ma, but, believe me, before this happened you’d have said that she hadn’t a drop of ambition in her. She was just a good fellow, contented to stay at home and look after things. Whereas pa and I were always saying if we were rich we’d do this and that. That was before I came over here. Well, along comes a lawyer’s letter one day for pa, saying that my Uncle Jim, somehow or other, had made more than a million out West, and he’d left it all to pa. And now ma, who used to be so quiet, has suddenly begun to show a flash of speed that would make you wonder why something don’t catch fire. She says we’re going into society, all in among all the dukes and earls and lord-high-main-squeezes. We’re going for a trip to Paris first. Afterwards I’m to be presented at Court. Have you seen an English fellow hanging around here, looking as if he’d bought the hotel and didn’t think much of it? He’s a lord. Hayling’s his name. Lord Arthur Hayling. Well, ma’s got acquainted and roped him in to be our barker. His job’s to stand in front of us with a megaphone and holler to Duke Percy and Lady Mabel to come in and see us. We’re going to take a fine big house somewhere, and Kid Hayling’s promised to see that folks are sociable. Halloa, there’s ma and his lordship, looking for me! Goodbye! Pleasant dreams.”

And the heiress rustled off.

That night Mr. Crump of Mervo arrived. He found John smoking in the hotel lobby, and wasted no time on preliminaries. “Mr. Maude?” he said. “I am Mr. Benjamin Scobell’s private secretary.”

“Yes?” said John. “Pretty snug job?”

The other seemed to miss something in his voice.

“You have heard of Mr. Scobell?” he asked.

“Not to my knowledge,” said John.

Mr. Crump was a young man of extraordinary gravity of countenance. He eyed John intently through a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles.

“I have been instructed,” he said, solemnly, “to inform your Highness that the Republic of Mervo has been dissolved, and that your subjects offer you the throne of your ancestors.”

John leaned back in his chair and looked at him in dumb amazement.

His attitude appeared to astound Mr. Crump.

“Don’t you know?” he said. “Your father——”

John became suddenly interested.

“If you’ve got anything to tell me about my father, go ahead. You’ll be the only man I’ve ever met who has said a word about him. Who the deuce was he?”

Mr. Crump’s face cleared.

“I understand. I had not expected this. You have been kept in ignorance. Your father, Mr. Maude, was the late Prince Charles of Mervo.”

John dropped his cigar in a shower of grey ash on to his trousers.

“If your Highness would glance at these documents—— This is a copy of the register of the church in which your mother and father were married.”

“But where the deuce is Mervo? I never heard of the place.”

“It is an island principality in the Mediterranean, your High ——”

“For goodness’ sake, old man, don’t keep calling me ‘your Highness.’ It may be fun to you, but it makes me feel a perfect ass. Let me get into the thing gradually.”

Mr. Crump felt in his pocket.

“Mr. Scobell,” he said, producing a roll of bank-notes, “entrusted me with money to defray any expenses.”

“That’s awfully good of him,” said John. “It strikes me, old man, that I am not absolutely up-to-date as regards the internal affairs of this important little kingdom of mine. How would it be if you were to tell me one or two facts? Start at the beginning and go right on.”

When Mr. Crump had finished a condensed history of Mervo and Mervian politics, John smoked in silence for some minutes.

“Well, well,” he said, “these are stirring times. When do we start for the old homestead?”

“Mr. Scobell was exceedingly anxious that we should start immediately.”

CHAPTER IV.

mr. scobell has another idea.

Owing to collaboration between Fate and Mr. Scobell, John’s State entry into Mervo was an interesting blend between a pageant and a music-hall sketch. The pageant idea was Mr. Scobell’s. The Palace Guard, forty strong, lined the quay. Besides these, there were four officers, a band, and sixteen mounted carbineers. The rest of the army was dotted along the streets. In addition to the military, there was a gathering of a hundred and fifty civilians, mainly drawn from fishing circles. They cheered vigorously as a young man, carrying a portmanteau, was seen to step on to the gangway and make for the shore. General Poineau, a white-haired warrior with a fierce moustache, strode forward and saluted. The Palace Guards presented arms. The band struck up the Mervian National Anthem. General Poineau, lowering his hand, put on a pair of pince-nez and began to unroll an address of welcome.

At this point Mr. Scobell made his presence felt.

“Glad to meet you, Prince,” he said, coming forward. “Scobell’s my name. Shake hands with General Poineau. No, that’s wrong. I suppose he kisses your hand, doesn’t he?”

“I’ll upper-cut him if he does,” said John, cheerfully.

Mr. Scobell eyed him doubtfully. His Highness did not appear to him to be treating the inaugural ceremony with that reserved dignity which we like to see in princes on these occasions. Mr. Scobell was a business man. He wanted his money’s worth. His idea of a Prince of Mervo was something statuesquely aloof, something—he could not express it exactly—on the lines of the illustrations in the Zenda stories, about eight feet high and shinily magnificent, something that would give the place a tone. That was what he had had in his mind when he sent for John. He did not want a cheerful young man in a Panama and a flannel suit, who appeared to regard the whole proceedings as a sort of pantomime rally.

“There’ll be breakfast at my villa, your Highness,” said Mr. Scobell. “My car is waiting along there.”

Then Mr. Scobell cheered up. Perhaps a Prince who took a serious view of his position would try to raise the people’s minds, and start reforms and generally be a nuisance. John could, at any rate, be relied upon not to do that. His face cleared.

“Have a good cigar, Prince?” he said, cordially, inserting two fingers in his vest-pocket.

“Good idea,” said his Highness, affably. “Thanks.”

Breakfast over, Mr. Scobell replaced the remains of his cigar between his lips and turned to business.

“I want you, Prince,” said Mr. Scobell, “to help boom this place. That’s where you come in.”

“Yes?” said John.

“As to ruling and all that,” continued Mr. Scobell, “there isn’t any to do. The place runs itself. Someone gave it a shove a thousand years ago, and it’s been rolling along ever since. What I want you to do is the picturesque business. Entertain swells when they come here. Have a Court—see what I mean?—like in England. Go round in aeroplanes, and that style of thing. Don’t you worry about money. That’ll be all right. You draw your steady twenty thousand a year, and a good bit more besides, when we begin to get moving.”

“Do I, by George?” said John. “It seems to me that I’ve fallen into a pretty soft thing here. There’ll be a catch somewhere, I suppose. There always is in these good things. But I don’t see it yet. You can count on me all right.”

“Good boy,” said Mr. Scobell. “And now you’ll he wanting to get to the palace. I’ll tell them to bring the car round.”

The Council of State broke up.

Having seen John off in the car, the financier proceeded to his sister’s sitting-room.

“Well,” said Mr. Scobell, “he’s come.”

“Yes, dear?”

“And he’s just the sort I want. Saw the idea of the thing right away, and is ready to do anything. No nonsense about him.”

“Is he married?” asked Miss Scobell.

Her brother started.

“Married? I never thought of that. But no, of course he’s not. He’d have mentioned it. He’s not the sort to hush up a thing like that. I——”

He stopped short. His green eyes gleamed excitedly.

“Marion!” he cried. “Hi, Marion!”

“Well, dear?”

“Listen. This thing is going to be big. I’ve got a new idea. It just came to me. Your saying that put it into my head. Do you know what I’m going to do? I’m going to wire to Betty to come over here, and I’m going to arrange a marriage between her and this Prince.”

Miss Scobell sighed.

“Very well, dear. I suppose you know best. But perhaps the Prince won’t like Betty!”

Mr. Scobell gave a snort of disgust.

“Marion,” he said, “you’ve got a mind like a slab of wet dough. Can’t you understand that the Prince is just as much in my employment as the man who scrubs the Casino steps? I’m hiring him to be Prince of Mervo, and his first job as Prince of Mervo will be to marry Betty. It’ll be a grand advertisement. ‘Restoration of Royalty at Mervo.’ That’ll make them take notice by itself. Then, biff! right on top of that, ‘Royal Romance—Prince Weds English Girl—Love at First Sight—Picturesque Wedding.’ We’ll wipe Monte Carlo clean off the map. We—— It’s the greatest scheme on earth. Here, where’s a telegraph form?”

CHAPTER V.

young adam cupid.

On a red sandstone rock at the edge of the water, where the island curved sharply out into the sea, Prince John of Mervo sat and brooded on First Causes. For nearly an hour and a half he had been engaged in an earnest attempt to trace to its source the acute fit of depression which had come—apparently from nowhere—to poison his existence that morning.

Then the thing stood revealed, beyond all question of doubt. What had unsettled him was that unexpected meeting with Betty Silver last night at the Casino.

He generally visited the Casino after dinner. As a rule he merely strolled through the rooms, watching the play; but last night he had slipped into a vacant seat. He had only just settled himself when he was aware of a girl standing beside him. He got up.

“Would you care——?” he had begun, and then he saw her face.

It had all happened in an instant. Some chord in him, numbed till then, had begun to throb. It was as if he had waked from a dream, or returned to consciousness after being stunned. There was something in the sight of her, standing there so cool and neat and composed in the heat and stir of the Casino, that struck him like a blow.

How long was it since he had seen her last? Not more than a couple of years. It seemed centuries.

He looked at her. And, as he looked, he heard England calling to him. Mervo, by the appeal of its novelty, had caused him to forget. But now, quite suddenly, he knew that he was home-sick.

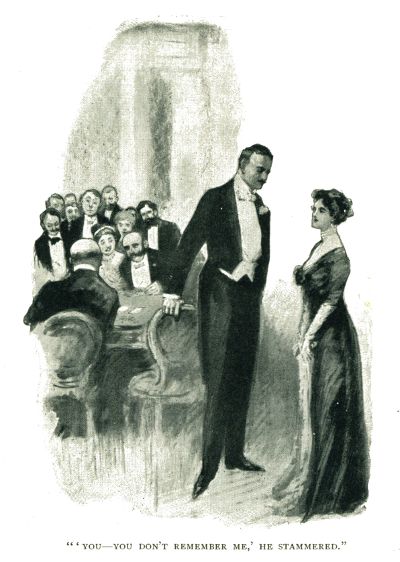

“You—you don’t remember me,” he stammered. She was flushing a little under his stare, but her eyes were shining.

“I remember you very well, Mr. Maude,” she said, with a smile.

“Won’t you take this seat?” said John.

“No, thank you. I’m not playing. I only just stopped to look on. My aunt is in one of the rooms, and I want to make her come home. I’m tired.”

“Have you been in Mervo long?” he said.

“I only arrived this morning. I was in England and my stepfather—I wonder if you know him—Mr. Scobell?”

“Mr. Scobell? Is he your stepfather?”

“Yes. He wired to me to come here. And I’m glad he did. It seems lovely. I must explore to-morrow.” She was beginning to move off.

“Er——” John coughed, to remove what seemed to him a deposit of sawdust and unshelled nuts in his throat. “Er—may I—will you let me show you some of the place to-morrow?”

“I should like it very much,” she said.

John made his big effort. He attacked the nuts and sawdust, which had come back and settled down again in company with a large lump of some unidentified material, and they broke before him. His voice rang out as if through a megaphone, to the unconcealed disgust of the neighbouring gamesters.

“If you go along the path at the foot of the hill,” he burst forth, rapidly, “and follow it down to the sea, you get to a little bay full of red sandstone rocks—you can’t miss it—and there’s a fine view of the island from there. I’d like awfully to show that to you. It’s lovely.”

“Then shall we meet there?” she said. “When?”

John was in no mood to postpone the event.

“As early as ever you like,” he said.

“At about ten, then. Good night, Mr. Maude.”

John had reached the bay at half-past eight, and had been on guard there ever since. It was now past ten, but still there were no signs of Betty. His depression increased. He told himself that she had forgotten. Then, that she had remembered, but had changed her mind. Then, that she had never meant to come at all.

His mood became morbidly introspective. He was weighed down by a sense of his own unworthiness. He submitted himself to a thorough examination, and the conclusion to which he came was that, as an aspirant to the regard of a girl like Betty, he did not score a single point.

He looked at his watch again, and the world grew black. It was half-past ten. He looked up the path for the hundredth time. Above him lay the hill-side, dozing in the morning sun; below, the Mediterranean, sleek and blue, without a ripple. But of Betty there was no sign.

CHAPTER VI.

mr. scobell is frank.

Much may happen in these rapid times in the course of an hour and a half. While John was keeping his vigil on the sandstone rock, Betty was having an interview with Mr. Scobell which was to produce far-reaching results.

The interview began, shortly after breakfast, in a gentle and tactful manner, with Aunt Marion at the helm. But Mr. Scobell was not the man to stand by silently while people were being tactful. At the end of the second minute he had plunged through his sister’s mild monologue like a rhinoceros through a cobweb.

“You say you want to know why you were wired for. I’ll tell you. I suppose you’ve heard that there’s a Prince here instead of a Republic now? Well, that’s where you come in.”

“Do you mean——” She hesitated.

“Yes, I do,” said Mr. Scobell. He went on rapidly. “This is a matter of State. You’ve got to drop fool notions and act for good of State. You’ve got to look at it in the proper spirit. Great honour—see what I mean? Princess, and all that. Chance of a lifetime. Dynasty. You’ve got to look at it in that way.”

Betty had not taken her eyes off him from his first word. The shock of his words had to some extent numbed her. Then her mind began to work actively once more.

“Do you mean that you want me to marry this Prince?” she said. “I won’t do anything of the sort.”

“Pshaw! Don’t be foolish.”

Betty’s eyes shone mutinously. Her cheeks were flushed, and her slim, boyish figure quivered. Her chin, always determined, became a silent Declaration of Independence.

“It’s ridiculous,” she said. “You talk as if you had just to wave your hand. Why should your Prince want to marry a girl he has never seen?”

“He will,” said Mr. Scobell, confidently.

“How do you know?”

“Because I know he’s a sensible young fellow. That’s how. You’re thinking that Mervo is an ordinary State, and that the Prince is one of those independent, all-wool, off-with-his-head rulers like you read about in the novels. Well, he isn’t. If you want to know who’s the big man here, it’s me—me! This Prince is simply my employé. See? Who sent for him? I did. Who put him on the throne? I did. Who pays him his salary? I do, from the profits of the Casino. Now do you understand? He knows his job. He knows which side his bread’s buttered. When I tell him about this marriage, do you know what he’ll say? He’ll say, ‘Thank you, sir!’ That’s how things are in this island.”

Betty shuddered. Her face was white with humiliation.

“There’s another thing,” said Mr. Scobell. “Perhaps you think he’s some kind of a foreigner? Perhaps that’s what’s worrying you. Let me tell you that he’s an Englishman—pretty nearly as English as you are yourself.”

Betty stared at him.

“An Englishman!”

“Don’t believe it, eh? Well, let me tell you that his mother was born in Birmingham, and that he has lived all his life in England. He’s no foreigner. He’s a Cambridge man, six feet high, and weighs thirteen stone. That’s the sort of man he is.”

Betty uttered a cry.

“Who is he?” she cried. “What was his name before he—when he——”

“His name?” said Mr. Scobell. “John Maude. Maude was his mother’s name. She was a Miss Westley. Here, where are you going?”

Betty was walking slowly towards the door. Something in her face checked Mr. Scobell.

“I want to think,” she said, quietly. “I’m going out.”

At half-past twelve that morning business took Mr. Benjamin Scobell to the Royal palace. He was not a man who believed in letting the grass grow under his feet. He prided himself on his briskness of attack.

In this matter of the Royal alliance it was his intention to have at it and clear it up at once. Having put his views clearly before Betty, he now proposed to lay them with equal clarity before the Prince.

Arriving at the palace, he was informed that his Highness had gone out shortly after breakfast and had not returned. He received the news equably, and directed his chauffeur to return to the villa. He could not have done better, for on his arrival he was met with the information that his Highness was waiting in the morning-room.

“Why, Prince,” said Mr. Scobell, “this is lucky. I’ve been looking for you.”

“Where is Miss Silver?” said John.

Mr. Scobell looked astonished.

“Do you know Betty?”

“I used to know her in England. We met last night at the Casino. I was to have met her again this morning, but”—he gulped—“but she didn’t come. I thought I should find her here.”

Mr. Scobell’s green eyes sparkled. There was no mistaking the tone of John’s voice. Fate was certainly smoothing his way.

“She’ll be here all right,” he said, consolingly. “I expect she forgot to keep the appointment. Now I think of it——”

There was a knock at the door. A footman entered, bearing a letter on a silver tray.

Mr. Scobell slit the envelope and began to read. As he did so his eyes grew round, and his mouth slowly opened till his cigar-stump, after hanging for a moment from his lower lip, dropped off like an exhausted bivalve and rolled along the carpet.

“Prince,” he gasped, “she’s gone! Betty!”

“Gone! What do you mean?”

“She’s half-way to Marseilles by now. Listen to what she says.

“ ‘By the time you read this I shall be gone. I am giving this to a boy to take to you after the boat has started. Please do not try and follow me to bring me back, for it will be no use. I shall never come back. I am going right away.’ ”

John was still staring.

“But why? Why should she go away like that? What could have made her do it?”

Mr. Scobell’s mouth had opened to explain, when a prudent instinct closed it. Something told him that this was no moment to reveal to John the scheme in which he was to have figured.

“Some fool notion, I suppose,” he said. “Girls are like that.”

John had begun to pace the room. Suddenly he stopped.

“I’m going after her,” he said.

Mr. Scobell beamed approval.

“Good for you, Prince,” he said. “Go to it!”

(To be concluded in two more instalments.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums